The Use of the Fraud Pentagon Model in Assessing the Risk of Fraudulent Financial Reporting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Target Population and Sample Data

3.2. Analyzed Variables and Proposed Econometric Models

- βi,i=0,…,8 represents the coefficients of the proposed model associated with each independent variable;

- ε represents the residual part or the error term of the econometric model, and the dependent and independent variables are presented in Table 4.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Robustness Test—Using Panel Data Analysis for Unobserved Heterogeneity and Multicollinearity

4.2. Reflections on the Implications of the Study

4.3. Research Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aivaz, Kamer-Ainur, Anamaria Mișa, and Daniel Teodorescu. 2024. Exploring the Role of Education and Professional Development in Implementing Corporate Social Responsibility Policies in the Banking Sector. Sustainability 16: 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, Taufiq. 2017. The determination of fraudulent financial reporting causes by using pentagon theory on manufacturing companies in Indonesia. International Journal of Business, Economics and Law 14: 106–13. [Google Scholar]

- Andriani, Kadek Fitri, Ketut Budiartha, Maria Mediatrix Ratna Sari, and Anak Agung Gde Putu Widanaputra. 2022. Fraud Pentagon Elements in Detecting Fraudulent Financial Statement. Linguistics and Culture Review 6: 686–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annisya, Mafiana, and Yuztitya Asmaranti. 2016. Fraud Diamond. Journal of Business and Economics 23: 72–89. [Google Scholar]

- Apriliana, Siska, and Linda Agustina. 2017. The Analysis of Fraudulent Financial Reporting Determinant through Fraud Pentagon Approach. Jurnal Dinamika Akuntansi 9: 154–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyanto, Dodik, I. Made Gilang Jhuniantaraa, Ni Made Dwi Ratnadia, I. Gusti Ayu Made Asri Dwija, and Ayu Aryista Dewi. 2021. Fraudulent Financial Statements in Pharmaceutical Companies: Fraud Pentagon Theory Perspective. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 24: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). 2022. Fraud Examiners Manual. Austin: ACFE. [Google Scholar]

- Bagus, Muhammad, Noviansyah Rizal, and Siwidyah Desi Lastianti. 2019. Determinant of Fraud Pentagon in Detecting Finance of Financial Statements. Jurnal Ilmiah Ilmu Akuntansi, Keuangan dan Pajak 4: 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawekes, H. F., A. M. A. Simanjuntak, and S. Christina Daat. 2018. Testing the Pentagon’s Fraud Theory Against Fraudulent Financial Reporting (Empirical Study of Companies Listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange in 2011–2015). Regional Journal of Accounting & Finance 13: 114–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bătae, Oana Marina, Voicu Dan Dragomir, and Liliana Feleagă. 2021. The relationship between environmental, social, and financial performance in the banking sector: A European study. Journal of Cleaner Production 290: 125791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimonaki, Christianna, Stelios Papasdakis, and Christos Lemonakis. 2023. All Fraud Theories: A Systematic Review Approach, 2004–2022. Available online: https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/856474/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Cordis, Adriana. 2024. Political alignment and corporate fraud: Evidence from the United States of America. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 25: 978–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressey, Donald R. 1953. Other People’s Money: A Study in the Social Psychology of Embezzlement. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, Horwath. 2011. Putting the Freud in Fraud: Why the Fraud Triangle Is No Longer Enough, in Horwath, Crowe. Available online: https://www.crowe.com/global (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Dechow, Patricia M., Weili Ge, Chad R. Larson, and Richard G. Sloan. 2011. Predicting Material Accounting Misstatements. Contemporary Accounting Research 28: 17–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, Putu Nirmala Chandra, Anak Agung Gde Putu Widanaputra, I. G. A. N. Budiasih, and Ni Ketut Rasmini. 2021. The Effect of Fraud Pentagon Theory on Financial Statements: Empirical Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 8: 1163–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Edelbacher, Maximilian. 2018. Fraud and Corruption: A European Perspective. In Fraud and Corruption. Edited by Peter C. Kratcoski and Maximilian Edelbacher. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evana, Einde, Mega Metalia, Edwin Mirfazli, Daniela Ventsislavova Georgieva, and Istianingsih Sastrodiharjo. 2019. Business Ethics in Providing Financial Statements: The Testing of Fraud Pentagon Theory on the Manufacturing Sector in Indonesia. Business Ethics and Leadership 3: 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farida, A., Dhian Wahyuni, and Putri Fariska. 2022. Determinant of the Fraud Pentagon Theory for Fraudulence Financial Reporting. Paper presented at 3rd Asia Pacific International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, September 13–15; p. 1150. [Google Scholar]

- Fathmaningrum, Erni Suryandari, and Gupita Anggarani. 2021. Fraud Pentagon and Fraudulent Financial Reporting: Evidence from Manufacturing Companies in Indonesia and Malaysia. Journal of Accounting and Investment 22: 625–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feleagă, Liliana Ionescu, Bogdan Stefan Ionescu, and Mariana Bunea. 2023. Do Board Diversity and High Performance Go Hand-In-Hand in the Banking Sector? Transformations in Business & Economics 22: 205. [Google Scholar]

- Fitriyah, Rif’atul, and Santi Novita. 2021. Fraud Pentagon Theory for Detecting Financial Statement Fraudulent. Jurnal Riset Akuntansi Kontemporer 13: 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuad, K., A. B. Lestari, and R. T. Handayani. 2020. Fraud Pentagon as a Measurement Tool for Detecting Financial Statements Fraud. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research 115: 87. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Dan. 2017. Researches of Detection of Fraudulent Financial Statements Based on Data Mining. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience 14: 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haqq, A. P. N. A., and Gideon Setyo Budiwitjaksono. 2020. Fraud Pentagon for Detecting Financial Statement Fraud. Journal of Economics, Business, and Accountancy Ventura 22: 319–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayah, Erna, and Galih Devi Saptarini. 2019. Pentagon Fraud Analysis in Detecting Potential Financial Statement Fraud of Banking Companies in Indonesia. Paper presented at 3rd International Conference on Accounting, Business & Economics, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, October 23–24; p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Husmawati, Pera, Yossi Septriani, Irda Rosita, and Desi Handayani. 2017. Handayani. Fraud pentagon analysis in assessing the likelihood of fraudulent financial statement. Paper presented at International Conference of Applied Science on Engineering, Business, Linguistics and Information Technology, Padang, Indonesia, October 13–15; pp. 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jaba, Elisabeta, Ioana-Alexandra Chirianu, Christiana Brigitte Balan, Ioan-Bogdan Robu, and Mihai Daniel Roman. 2016a. The analysis of the effect of women’s participation in the labor market on fertility in European union countries using welfare state models. Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies and Research 50: 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jaba, Elisabeta, Ioan-Bogdan Robu, Costel Istrate, Christiana Brigitte Balan, and Mihai Roman. 2016b. Statistical Assessment of the Value Relevance of Financial Information Reported by Romanian Listed Companies. Romanian Journal of Economic Forecasting 19: 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jaba, Elisabeta, Ioan-Bogdan Robu, and Christiana Brigitte Balan. 2017. Panel data analysis applied in financial performance assessment. Romanian Statistical Review 65: 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Yossi, Hayatul Fadzillah Joshi, and Anda Dwi Haryadi. 2022. Detecting potential financial statement fraud using fraud pentagon analysis. Indonesia’s manufacturing firms’ evidence. Review of Accounting, Finance and Governance 2: 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mironiuc, Marilena, Ioan-Bogdan Robu, and Mihaela-Alina Robu. 2012. The Fraud Auditing: Empirical Study Concerning the Identification of the Financial Dimensions of Fraud. Journal of Accounting and Auditing: Research & Practice 2012: 180. [Google Scholar]

- Mottinger, Markus. 2024. Corruption and audit fees: New evidence from EU27 countries. International Journal of Auditing 28: 717–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, Satria Tri, Raisya Zenita, and Neneng Salmiah. 2019. Fraudulent Financial Reporting: A Fraud Pentagon Analysis. Accounting and Finance Review 4: 110. [Google Scholar]

- Nizarudin, Abu, Ari Agung Nugroho, and Duwi Agustina. 2023. Comparative Analysis of Crowe’s Fraud Pentagon Theory on Fraudulent Financial Reporting. Jurnal Akuntansi 27: 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, Arief Himmawan Dwi, Muhammad Ardinata, and Rofidah Yunita Ambarsari. 2020. The Effectiveness of Pentagon Fraud in Detecting Fraudulent Financial Reporting: Using the Beneish Model in Manufacturing Companies on the Indonesia Stock Exchange. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research 169: 389–94. [Google Scholar]

- Nurbaiti, Zulvi, and Rustam Hanafi. 2017. Analisis Pengaruh Fraud Diamond Dalam Mendeteksi Tingkat Accounting Irregularities. Jurnal Akuntansi Indonesia 6: 167–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nurcahyono, Nurcahyono, and Ayu Noviani Hanum. 2023. Determinants of Academic Fraud Behavior: The Perspective of the Pentagon Fraud Theory. Paper presented at 1st Lawang Sewu International Symposium on Humanities and Social Sciences, Semarang, Indonesia, November 29; pp. 163–77. [Google Scholar]

- Osadchy, E. A., E. M. Akhmetshin, E. F. Amirova, T. N. Bochkareva, Yu Yu Gazizyanova, and A. V. Yumashev. 2018. Financial Statements of a Company as an Information Base for Decision-Making in a Transforming Economy. European Research Studies Journal XXI: 340. [Google Scholar]

- Puspitha, Made Yessi, and Gerianta Wirawan Yasab. 2018. Fraud Pentagon Analysis in Detecting Fraudulent Financial Reporting. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research 42: 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Puspitosari, Indriyana. 2022. Fraud Triangle Theory on Online Academic Cheating Accounting Students. Accounting and Finance Studies 2: 229–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, Dona. 2020. Root Cause Analysis Using Fraud Pentagon Theory Approach (A Conceptual Framework). Asia Pacific Fraud Journal 5: 118–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Sofia, Jose A. Perez-Lopez, Rute Abreu, and Sara Nunes. 2024. Impact of fraud in Europe: Causes and effects. Heliyon 10: e40049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Scott A., Richard G. Sloan, Mark T. Soliman, and Irem Tuna. 2005. Accrual reliability, earnings persistence and stock prices. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39: 437–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimadanti, Shevina, Aprih Santoso, and Ardiani Ika Sulistyawati. 2022. The Role of Pentagon Fraud in Detecting Fraudulent Financial Statements. Golden Ratio of Finance Management 2: 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukmana, Heru Satria. 2021. Determinants of Pentagon Fraud in Detecting Financial Statement Fraud and Company Value. Majalah Ilmiah Bijak 18: 110–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sahla, Widya Ais, and Ardianto Ardianto. 2023. Ethical values and auditors fraud tendency perception: Testing of fraud pentagon theory. Journal of Financial Crime 30: 966–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchter, Alexander, and Michael Levi. 2016. The Fraud Triangle revisited. Security Journal 29: 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septriani, Yossi, and Desi Handayani. 2018. Mendeteksi kecurangan laporan keuangan dengan analisis fraud pentagon. Jurnal Akuntansi, Keuangan Dan Bisnis 11: 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Setiawati, Erma, and Ratih Mar Baningrum. 2018. Deteksi fraudulent financial reporting menggunakan analisis fraud pentagon: Studi kasus pada perusahaan manufaktur yang listed di BEI tahun 2014–2016. Riset Akuntansi dan Keuangan Indonesia 3: 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situngkir, Naomi Clara, and Dedik Nur Triyanto. 2020. Detecting fraudulent financial reporting using fraud score model and fraud pentagon theory: Empirical study of companies listed in the LQ 45 Index. The Indonesian Journal of Accounting Research 23: 373–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylwestrzak, Marek. 2022. Using a hybrid model to detect earnings management for Polish public companies. Journal of International Studies 15: 158–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessa, G. Chyntia, and Puji Harto. 2016. Fraudulent Financial Reporting: Pengujian Teori Fraud Pentagon pada Sektor Keuangan dan Perbankan di Indonesia. Simposium Nasional Akuntansi XIX: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tjahjani, Fera, Briantama Maulidza Rizky, Widanarni Pudjiastuti, and Nawang Kalbuana. 2022. Fraud Pentagon Theory: Indication Toward Fraudulent Financial Reporting on Non-Banking Sector. International Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting Research 6: 1352. [Google Scholar]

- Triandi, S. M. 2019. Analysis of Fraudulent Financial Reporting Through the Fraud Pentagon Theory. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research 143: 214. [Google Scholar]

- Ulfah, Maria, Elva Nuraina, and Anggita Langgeng Wijaya. 2017. The impact of fraud diamond in detecting financial statement fraud (empirical study Indonesian banking listed on Indonesia Stock Exchange). The 9th Forum Ilmiah Pendidikan Akuntansi (FIPA) 5: 399–417. [Google Scholar]

- Utami, Dhita Permata Wira, and Dian Indri Purnamasari. 2021. The impact of ethics and fraud pentagon theory on academic fraud behavior. Journal of Business and Information Systems 3: 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Utami, Evy Rahman, and Nandya Octanti Pusparini. 2019. The Analysis of Fraud Pentagon Theory and Financial Distress for Detecting Fraudulent Financial Reporting in Banking Sector in Indonesia (Empirical Study of Listed Banking Companies on Indonesia Stock Exchange in 2012–2017). Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research 102: 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Vancea, Diane Paula Corina, Kamer Ainur Aivaz, and Cristina Duhnea. 2017. Political Uncertainty and Volatility on the Financial Markets—The Case of Romania. Transformations in Business & Economics 16: 457. [Google Scholar]

- Vancea, Diane Paula Corina, Kamer Ainur Aivaz, Luciana Simion, and Diana Vanghele. 2021. Export Expansion Policies. An Analysis of Romanian Exports Between 2005–2020 Using the Principal Component Analysis Method and Short Recommandations for Increasing this Activity. Transformations in Business & Economics 20: 614–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vousinas, Georgios L. 2019. Advancing theory of fraud: The S.C.O.R.E. model. Journal of Financial Crime, Emerald Group Publishing Limited 26: 372–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, Joseph T. 2009. Fraud: The Occupational Hazards. Accountancy Age, January 29. Available online: https://www.accountancyage.com/2009/01/29/fraud-the-occupational-hazards/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Wolfe, David T., and Dana R. Hermanson. 2004. The Fraud Diamond: Considering the Four Elements of Fraud. The CPA Journal, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yanti, Jasella Sakwi, Yossi Diantimala, and Nuraini A. 2024. Testing the Crowes Pentagon Theory of Fraud on Financial Statement Fraud. International Journal of Management, Accounting and Economics 11: 296–309. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, Khairusany Mohamed. 2016. Fraudulent Financial Reporting: An Application of Fraud Models to Malaysian Public Listed Companies. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Hull, Hull, UK; pp. 1–430. [Google Scholar]

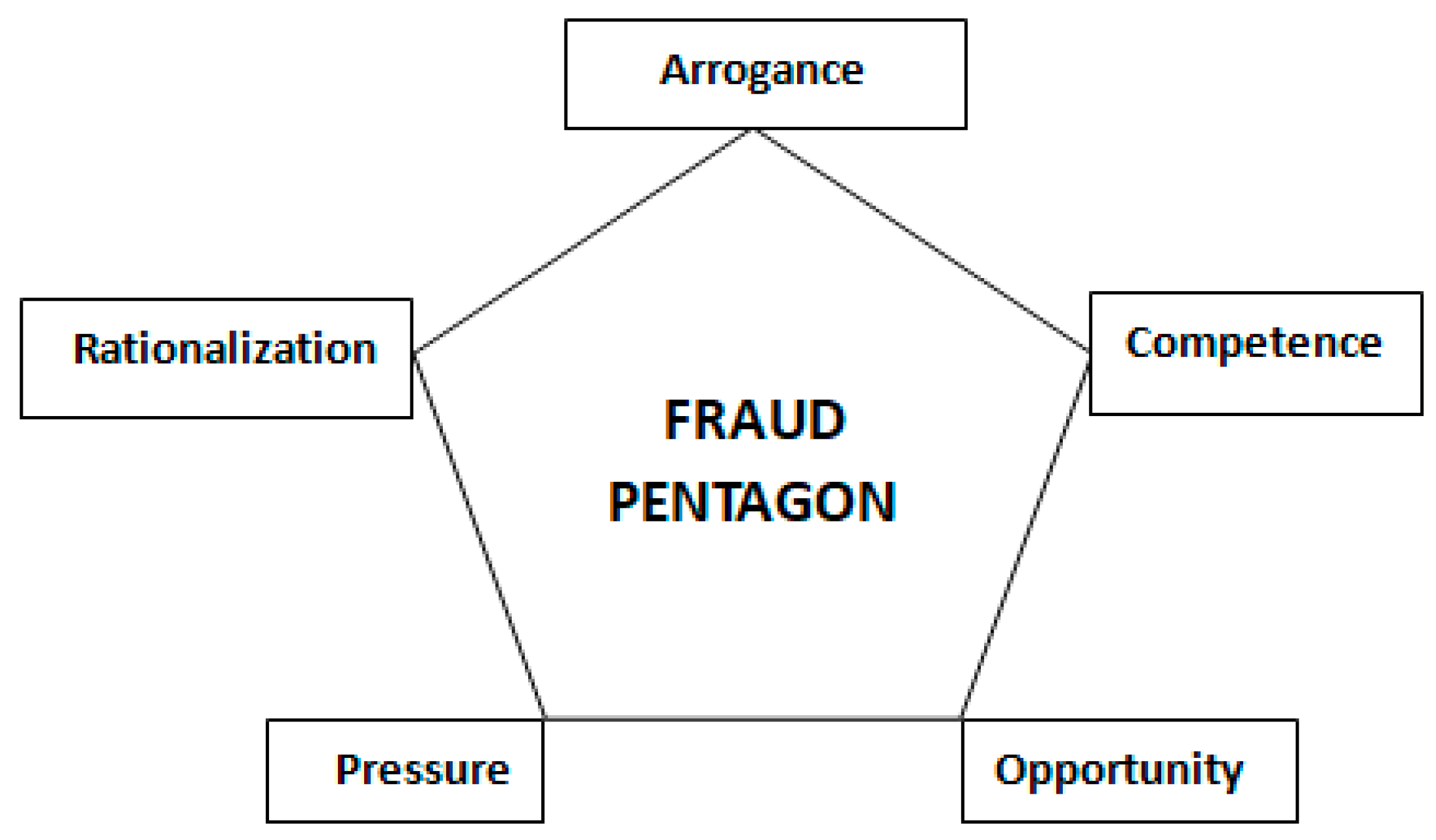

| Fraudulent Financial Reporting (FFR) | Pressure (P) |

|

| Opportunity (O) |

| |

| Rationalization (R) |

| |

| Capability/Competence (C) |

| |

| Arrogance (A) |

|

| Authors and Year of the Research Study | Analyzed Period | Sample Analyzed | FFR | Country | Factors from Fraud Pentagon | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (P) | (O) | (R) | (C) | (A) | |||||

| (Evana et al. 2019) | 2013–2015 | 59 companies, 177 observations | F-score | Indonesia | ⮽ | ⮽ | ☑ | ☑ | ⮽ |

| (Hidayah and Saptarini 2019) | 2013–2017 | 38 banking companies | F-score Panel data regression analysis | Indonesia | ☑ | ⮽ | ⮽ | ☑ | ⮽ |

| (Ramadhan 2020) | 2017–2018 | 144 companies | RCA-FP | Indonesia | ☑ | ⮽ | ☑ | ☑ | ⮽ |

| (Devi et al. 2021) | 2014–2019 | 20 companies | F-Score | Indonesia | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ |

| (Fathmaningrum and Anggarani 2021) | 2017–2018 | 118 companies | Modified Jones, multiple linear regression analysis | Indonesia, Malaysia | ☑ | ☑ | ⮽ | ⮽ | ⮽ |

| (Rukmana 2021) | 2012–2016 | 66 companies | Panel data regression analysis | Indonesia | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | ⮽ | ☑ |

| (Andriani et al. 2022) | 2015–2019 | 62 companies | Logistic regression analysis and discriminant analysis | Indonesia | ☑ | ⮽ | ⮽ | ⮽ | ⮽ |

| (Tjahjani et al. 2022) | 2017–2019 | 111 companies | Logistic regression analysis | Indonesia | ⮽ | ⮽ | ⮽ | ⮽ | ⮽ |

| (Joshi et al. 2022) | 2019–2021 | 126 companies, IDX | Logistic regression analysis | Indonesia | ☑ | ⮽ | ☑ | ⮽ | ⮽ |

| (Yanti et al. 2024) | 2017–2021 | 131 companies | Multiple linear regression analysis | Indonesia | ☑ | ☑ | ⮽ | ☑ | ⮽ |

| Year | Observations |

| 2017 | 62 |

| 2018 | 62 |

| 2019 | 62 |

| 2020 | 62 |

| 2021 | 62 |

| Total sample firm/year observations | 310 |

| Dependent Variable | Calculation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Fraudulent financial reporting (FFR) | Dechow F-score F-Score = Accrual quality + Financial Performance | Richardson et al. (2005) Dechow et al. (2011) |

| Independent variables | Calculation | Reference |

| Return on assets (ROA) | Net Profit/Total Asset | Bawekes et al. (2018) |

| Financial stability (ACHANGE) | (Total Assett − Total Assett−1)/Total Assett | Akbar (2017) |

| External pressure (LEV) | Total debts/Total assets | Annisya and Asmaranti (2016) |

| External auditor quality (BIG4) | Dummy variable: code 1 if the company uses the audit services of the Big Four, and code 0 if the company does not use the audit service of the Big Four | Apriliana and Agustina (2017) |

| Nature of industry (NI) | (Receivablest/Salest) − (Receivablest−1/Salest−1) | |

| Changes in auditor (CHIA) | Dummy variable: code 1 for companies that implement change in auditors and code 0 for companies that do not carry out a change in auditors | Fathmaningrum and Anggarani (2021) |

| Change of directors (DCHANGE) | Dummy variable: code 1 for companies that carry out a change in directors and code 0 for companies that do not change directors | Fitriyah and Novita (2021) |

| Number of CEO’s pictures (CEOPIC) | Total photos of CEOs emblazoned in an annual report of the company | Hidayah and Saptarini (2019) |

| Variables | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFR | 248 | 0.000 | 19.140 | 0.994 | 2.299 |

| ROA | 248 | −0.810 | 1.260 | 0.028 | 0.133 |

| ACHANGE | 248 | −0.580 | 1.910 | 0.065 | 0.232 |

| LEV | 248 | 0.020 | 5.680 | 0.495 | 0.707 |

| BIG4 | 248 | 0 (24.6%) | 1 (75.4%) | - | - |

| NI | 248 | −4.780 | 9.730 | 0.076 | 0.997 |

| CHIA | 248 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.105 | 0.307 |

| DCHANGE | 248 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.012 | 0.110 |

| CEOPIC | 248 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.032 | 0.177 |

| Valid N | 248 |

| FFR | ROA | ACHANGE | LEV | BIG4 | NI | CHIA | DCHANGE | CEOPIC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFR | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.191 ** | −0.122 | −0.041 | −0.051 | 0.071 | −0.028 | −0.023 | −0.038 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.003 | 0.055 | 0.523 | 0.423 | 0.268 | 0.660 | 0.718 | 0.551 | ||

| N | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | |

| ROA | Pearson Correlation | 0.191 ** | 1 | 0.172 ** | −0.378 ** | 0.052 | 0.140 * | −0.035 | −0.012 | 0.002 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.415 | 0.027 | 0.584 | 0.845 | 0.973 | ||

| N | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | |

| ACHANGE | Pearson Correlation | −0.122 | 0.172 ** | 1 | −0.057 | 0.065 | −0.075 | −0.061 | −0.051 | 0.016 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.055 | 0.007 | 0.375 | 0.307 | 0.239 | 0.337 | 0.421 | 0.808 | ||

| N | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | |

| LEV | Pearson Correlation | −0.041 | −0.378 ** | −0.057 | 1 | −0.096 | 0.001 | −0.029 | −0.063 | −0.019 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.523 | 0.000 | 0.375 | 0.131 | 0.986 | 0.654 | 0.321 | 0.767 | ||

| N | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | |

| BIG4 | Pearson Correlation | −0.051 | 0.052 | 0.065 | −0.096 | 1 | 0.052 | −0.043 | −0.063 | 0.320 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.423 | 0.415 | 0.307 | 0.131 | 0.418 | 0.504 | 0.322 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | |

| NI | Pearson Correlation | 0.071 | 0.140 * | −0.075 | 0.001 | 0.052 | 1 | 0.084 | −0.066 | −0.009 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.268 | 0.027 | 0.239 | 0.986 | 0.418 | 0.185 | 0.300 | 0.893 | ||

| N | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | |

| CHIA | Pearson Correlation | −0.028 | −0.035 | −0.061 | −0.029 | −0.043 | 0.084 | 1 | −0.038 | −0.062 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.660 | 0.584 | 0.337 | 0.654 | 0.504 | 0.185 | 0.553 | 0.327 | ||

| N | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | |

| DCHANGE | Pearson Correlation | −0.023 | −0.012 | −0.051 | −0.063 | −0.063 | −0.066 | −0.038 | 1 | −0.020 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.718 | 0.845 | 0.421 | 0.321 | 0.322 | 0.300 | 0.553 | 0.752 | ||

| N | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | |

| CEOPIC | Pearson Correlation | −0.038 | 0.002 | 0.016 | −0.019 | 0.320 ** | −0.009 | −0.062 | −0.020 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.551 | 0.973 | 0.808 | 0.767 | 0.000 | 0.893 | 0.327 | 0.752 | ||

| N | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 | |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regression | 24,630,083 | 8 | 3078.760 | 2.177 | 0.030 |

| Residual | 338,034,416 | 239 | 1414.370 | |||

| Total | 362,664,499 | 247 | ||||

| Model from Equation (1) | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Std. Error | β | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 9.012 | 3.732 | 2.415 | 0.017 | |

| ROA | 64.528 | 19.975 | 0.224 | 3.231 | 0.001 | |

| ACHANGE | −25.932 | 10.585 | −0.157 | −2.450 | 0.015 | |

| LEV | 1.473 | 3.690 | 0.027 | 0.399 | 0.690 | |

| BIG4 | −4.222 | 5.914 | −0.048 | −0.714 | 0.476 | |

| NI | 1.181 | 2.460 | 0.031 | 0.480 | 0.632 | |

| CHIA | −4.527 | 7.876 | −0.036 | −0.575 | 0.566 | |

| DCHANGE | −10.293 | 22.045 | −0.029 | −0.467 | 0.641 | |

| CEOPIC | −4.964 | 14.289 | −0.023 | −0.347 | 0.729 | |

| Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (b) Fixed | (B) Random | (b-B) Differences | Sqrt(diag(V_b-V_B)) S.E. |

| ROA | 92.550 | 64.562 | 27.989 | 16.775 |

| ACHANGE | −23.778 | −25.933 | 2.155 | 6.191 |

| LEV | −6.994 | 1.446 | −8.440 | 20.112 |

| BIG4 | 2.100 | −4.237 | 6.338 | 24.442 |

| NI | 0.611 | 1.171 | −0.560 | 0.817 |

| CHIA | −8.099 | −4.697 | −3.402 | 4.517 |

| DCHANGE | −14.892 | −10.519 | −4.373 | 12.085 |

| Random Effects Model | Coef. | Std. Error | z | P > |z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 9.097 | 3.759 | 2.42 | 0.016 |

| ROA | 64.562 | 19.886 | 3.25 | 0.001 |

| ACHANGE | −25.933 | 10.558 | −2.46 | 0.014 |

| LEV | 1.446 | 3.719 | 0.39 | 0.477 |

| BIG4 | −4.237 | 5.962 | −0.71 | 0.477 |

| NI | 1.171 | 2.455 | 0.48 | 0.633 |

| CHIA | −4.697 | 7.876 | −0.60 | 0.551 |

| DCHANGE | −10.519 | 22.043 | −0.48 | 0.633 |

| CEOPIC | −5.058 | 14.414 | −0.35 | 0.726 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burlacu, G.; Robu, I.-B.; Anghel, I.; Rogoz, M.E.; Munteanu, I. The Use of the Fraud Pentagon Model in Assessing the Risk of Fraudulent Financial Reporting. Risks 2025, 13, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060102

Burlacu G, Robu I-B, Anghel I, Rogoz ME, Munteanu I. The Use of the Fraud Pentagon Model in Assessing the Risk of Fraudulent Financial Reporting. Risks. 2025; 13(6):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060102

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurlacu, Georgiana, Ioan-Bogdan Robu, Ion Anghel, Marius Eugen Rogoz, and Ionela Munteanu. 2025. "The Use of the Fraud Pentagon Model in Assessing the Risk of Fraudulent Financial Reporting" Risks 13, no. 6: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060102

APA StyleBurlacu, G., Robu, I.-B., Anghel, I., Rogoz, M. E., & Munteanu, I. (2025). The Use of the Fraud Pentagon Model in Assessing the Risk of Fraudulent Financial Reporting. Risks, 13(6), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13060102