1. Introduction

The portfolio selection problem has been a cornerstone of modern finance since the seminal work of

Markowitz (

1952), who introduced the mean–variance (MV) model as the first rigorous quantitative approach to balancing risk and return. By maximizing expected return for a given level of risk or minimizing risk for a given level of return, the MV model established the foundations of modern portfolio theory and remains a fundamental reference in both academia and practice. Despite its theoretical elegance, the model assumes normally distributed returns, requires precise estimates of variances and covariances, and often generates unstable allocations in the presence of small sample sizes or heavy-tailed return distributions. These limitations have motivated the development of richer frameworks that go beyond the simplifying assumptions of normality.

To address such shortcomings, alternative risk measures have been proposed.

Konno and Yamazaki (

1991) introduced the mean absolute deviation as a more robust metric,

Speranza (

1993) formulated semi-deviation models, while

King and Jensen (

1992) and

King (

1993) developed semi-variance approaches more consistent with the asymmetric perception of losses by investors.

Markowitz et al. (

1993) extended the model to mean–semi-variance optimization. These contributions highlighted the need to capture risk in ways that are more consistent with observed market behavior. Risk measures such as Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) (

Rockafellar and Uryasev 2000) became widely used for quantifying extreme downside risk, particularly in regulatory settings. While these approaches advanced portfolio theory, they often face estimation error, model misspecification, and limited tractability.

Another line of research draws on information theory.

Shannon (

1948) introduced entropy as a measure of uncertainty, later applied to finance by

Philippatos and Wilson (

1972), who demonstrated its ability to capture diversification effects. Entropy provides a distribution-free and nonlinear measure of uncertainty, making it especially suitable for complex markets. Empirical studies and reviews (e.g.,

Simonelli 2005;

Zhou et al. 2013) confirm entropy’s role as a versatile and theoretically grounded measure of portfolio diversification. Subsequent extensions, such as

Tsallis (

1988),

Rényi (

1970), and

Kaniadakis (

2002), have generalized Shannon’s concept to better handle heavy tails and nonlinear dependencies. More recent work has applied entropy in areas such as systemic risk measurement, large-scale optimization, and crypto-asset allocation.

Despite these advances, most entropy-based approaches rely on the classical Shannon entropy, which implicitly assumes that all assets are equally informative. This neglects heterogeneity in asset characteristics such as volatility, liquidity, or market capitalization, which are central to realistic portfolio decisions.

Guiasu (

1971) introduced the Weighted Shannon Entropy (WSE), which incorporates asset-specific informational weights, thereby extending the classical framework with an additional layer of modeling flexibility. While WSE has found applications in statistics and decision theory, its use in portfolio optimization remains limited, and few studies have empirically tested its potential in financial markets. Parallel to deviation-based measures, alternative paradigms have emerged. Expected utility theory (

von Neumann and Morgenstern 1944) and Prospect Theory (

Kahneman and Tversky 1979) emphasize investor preferences and behavioral aspects, though they often rely on strong assumptions about utility functions and probability distortions (

He and Jiang 2020;

Liu and Li 2023;

Sheraz and Dedu 2020)

. In addition, recent studies on cryptocurrency market behavior and entropy-based portfolio construction highlight the relevance of robust diversification methods in highly volatile digital-asset environments, further motivating the use of WSE in this context (

Sensoy and Yarovaya 2022;

Ortega and Requeijo 2023;

López de Prado 2021).

This paper addresses this research gap and contributes in three main directions:

It develops a formal optimization model that integrates Weighted Shannon Entropy into portfolio construction, deriving analytical solutions through the maximum entropy principle and Lagrange multipliers.

It applies the model to cryptocurrency portfolios, a context characterized by volatility, fat tails, and unstable correlations, providing a timely and relevant empirical testbed.

It benchmarks WSE allocations against equal-weight and mean–variance portfolios, extending the analysis with robustness checks under alternative weighting schemes and with risk-adjusted performance indicators such as the Sharpe ratio and CVaR.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the theoretical foundations of the WSE optimization framework and outlines the empirical design.

Section 3 discusses the numerical results and comparative performance.

Section 4 concludes with implications and directions for future research. Beyond these theoretical developments, the increasing instability of modern financial markets—characterized by structural breaks, regime shifts, and nonlinear dependencies—has intensified the need for portfolio models that remain robust under uncertainty. In particular, cryptocurrency markets represent an extreme case of such environments, where traditional variance-based estimators often fail to capture tail risk and dependence asymmetries. These challenges motivate the integration of entropy-based principles into risk management, as entropy offers a distribution-free mechanism for mitigating concentration and enhancing resilience. Weighted Shannon Entropy, by incorporating asset-specific informational cues, bridges the gap between classical diversification rules and real-world market microstructure. As a result, the present study positions WSE not only as a mathematical extension of existing entropy measures but as a practical and theoretically grounded tool for constructing portfolios that maintain stability despite high volatility and parameter uncertainty. This dual perspective—methodological rigor combined with empirical relevance—underpins the contribution of our work and frames the analysis that follows.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Weighted Shannon Entropy: Theoretical Background

Entropy, as introduced by

Shannon (

1948), is defined for a discrete probability distribution

,

. Shannon entropy is defined as

In portfolio theory, the vector

can be reinterpreted as the allocation weights across

N assets. While entropy has been widely used as a diversification measure, it implicitly assumes that all assets carry equal informational importance. To relax this assumption,

Guiasu (

1971) proposed the Weighted Shannon Entropy (WSE):

are informational weights. Throughout the paper, all mathematical symbols are standardized as follows:

denotes portfolio weights,

informational weights,

the expected return, and

the variance of portfolio returns. In our framework,

pi are portfolio weights (fractions of wealth allocated to asset

i), not probability measures in the strict statistical sense. Short-selling is excluded, consistent with the non-negativity condition p

i ≥ 0. The weights

can represent asset-specific features such as inverse volatility, market capitalization, or liquidity, thereby providing WSE with clear financial meaning. When all

= 1, the WSE reduces to classical Shannon entropy. A higher WSE indicates a more diversified and balanced allocation, while lower values reflect portfolio concentration. Thus, entropy serves as a structural proxy for diversification and, indirectly, liquidity. In this context, the inverse of volatility is interpreted as a proxy for informational reliability, assigning greater importance to assets with more stable return dynamics. Alternative definitions of

based on market capitalization or trading volume were also tested to verify the robustness of results. Moreover, incorporating multiple weighting schemes allows the WSE framework to capture complementary dimensions of market structure, ensuring that the resulting allocations remain stable across different liquidity conditions and microstructural regimes.

2.2. Maximum Entropy Optimization Problem

We consider a portfolio of

N assets, with weights

,

. The optimization problem is formulated as:

where μ

i denotes the expected return of asset

i,

the target return, and

the variance–covariance matrix of asset returns. This formulation extends the classical mean–variance optimization by incorporating entropy as a diversification-enhancing term. Unlike the original Markowitz model, which relies solely on return and variance, the inclusion of entropy penalizes excessive concentration and fosters liquidity-aware diversification.

Informational weights may be chosen through several optimization procedures. Common approaches include inverse-volatility or inverse-variance schemes, liquidity-adjusted weighting based on trading activity or market depth, and data-driven optimization where is selected to minimize portfolio concentration or maximize a diversification index. Alternatively, can be calibrated using cross-validation or rolling-window procedures to enhance out-of-sample robustness. These options allow practitioners to tailor the entropy component to their informational preferences and market conditions.

2.3. Solution via the Method of Lagrange Multipliers

The Lagrangian function of the problem is:

where λ, γ, η ≥ 0 are Lagrange multipliers associated with the budget, return, and variance constraints, respectively.

The first-order conditions is: = − = 0.

The first-order conditions yield exponential-form (softmax) solutions:

To provide additional mathematical transparency, we outline the intermediate steps leading from the Lagrangian to the softmax-type solution. The first-order condition with respect to each portfolio weight p

i has the general form:

Rearranging this expression gives:

where C groups together all constant terms (including λ). Exponentiating both sides yields a proportionality relation:

The budget constraint Σp

i = 1 then provides the normalization factor, producing the exponential (softmax-type) portfolio weights discussed in the main text. When the variance constraint is inactive (η = 0), the expression simplifies considerably. The solution reduces to:

which corresponds to the classical maximum-entropy allocation under linear return constraints.

This system of equations yields the optimal weights.

When the variance constraint is inactive (η = 0), the solution simplifies to a softmax form in returns. When variance is active, the optimization must be solved numerically (e.g., Sequential Least Squares Quadratic Programming-SLSQP).

2.4. Portfolio Optimization Under Mean and Variance Constraints

The integration of Weighted Shannon Entropy into the portfolio selection problem provides a structural mechanism to balance expected return, variance, and diversification. While entropy maximization alone yields softmax-type allocations, realistic investment problems must also account for mean–variance trade-offs. Accordingly, the optimization model can be reformulated as a multi-objective problem:

where

are preference parameters reflecting the investor’s trade-off between return and diversification.

By embedding entropy into the optimization framework, the model simultaneously balances expected return, risk, and diversification, achieving solutions that are less sensitive to estimation errors compared to variance-only approaches. This integrated formulation ensures that the optimization model remains stable and consistent across different sample horizons, ranging from short-term evaluation windows to the full one-year dataset, thereby confirming its robustness under varying market regimes. By combining entropy with the classical mean–variance structure, the model preserves the traditional risk–return trade-off while simultaneously penalizing excessive concentration and promoting balanced allocations. Preference parameters and can be introduced to explicitly encode the investor’s attitude toward return maximization versus diversification, with typical choices such as and reflecting a moderate profile that values performance without sacrificing structural stability.

The variance constraint is explicitly quadratic in the allocation vector.

This ensures consistency with the covariance-based definition of risk and avoids the approximation errors sometimes introduced by diagonal variance specifications. In practice, solving this problem requires numerical optimization, which we perform using Sequential Least Squares Quadratic Programming (SLSQP). This approach accommodates both linear constraints (budget, non-negativity) and the nonlinear quadratic constraint (variance), providing stable and tractable solutions even for larger portfolios.

2.5. Case Studies: Cryptocurrency Portfolio

2.5.1. Data Description

Small portfolio (N = 4, Jan–Mar 2025): BTC, ETH, SOL, BNB.

Extended portfolio (N = 12, Apr 2024–Mar 2025): BTC, ETH, SOL, BNB, ADA.

XRP, DOGE, DOT, AVAX, MATIC, LTC, TRX. The empirical analysis focuses on the cryptocurrency market, chosen for its volatility, heavy-tailed distributions, and frequent structural breaks. Daily closing prices were obtained from the Binance exchange via the TradingView platform. The dataset spans a full twelve-month horizon from April 2024 to March 2025, covering both bullish and bearish regimes.

Returns were computed as daily log-returns, and variances and covariances were estimated using rolling windows of 30 trading days. To ensure realism, proportional transaction costs of 0.1% per trade were included, and monthly rolling rebalancing was applied to update portfolio weights dynamically.

2.5.2. Implementation of WSE Optimization

The optimization problem was solved under three informational weighting schemes:

Inverse volatility weights—assets with lower historical volatility receive higher informational weight.

Market capitalization weights—assets with higher market value are considered more informative.

Trading volume weights—assets with higher liquidity receive higher informational relevance.

For benchmarking, results were compared with:

The model parameters were calibrated with α = 0.75 for expected return and β = 0.25 for entropy, reflecting a moderate investor profile prioritizing return while maintaining diversification.

Figure 1 graphically illustrates the allocation differences between Equal Weight (EW) and Weighted Shannon Entropy (WSE) portfolios for the twelve-asset cryptocurrency universe. The chart highlights how WSE increases allocations to stable assets such as BTC and ETH, while reducing exposure to volatile smaller coins, thereby confirming its structural diversification role.

Robustness checks using all three schemes—inverse volatility, market capitalization, and trading volume—produced consistent allocations and confirm the methodological soundness of the WSE framework.

2.5.3. Empirical Setup

Two configurations were analyzed:

Small portfolio (N = 4) consisting of BTC, ETH, SOL, and BNB over January–March 2025, to illustrate the proof-of-concept.

For the extended case study, we consider N = 12 cryptocurrencies with weekly data, apply rolling rebalancing, and include proportional transaction costs of 0.1% per trade.

The extended dataset captures both bullish phases (e.g., Q2, 2024) and bearish corrections (Q4, 2024), allowing us to evaluate the stability of WSE under different market regimes.

2.5.4. Performance Measures

Performance was assessed using the following indicators:

Expected return ()

Portfolio variance ()

Entropy score (

Sharpe ratio: S = (Given the absence of a well-defined risk-free rate in crypto markets, we set rf = 0 (risk-free rate, following standard practice in empirical crypto- finance studies))

Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR) at 95% confidence

These metrics allow for a comprehensive evaluation of both diversification and risk-adjusted performance.

Figure 2 shows the Sharpe ratio comparison for portfolios optimized under the Mean–Variance (MV), Shannon Entropy (SE), and Weighted Shannon Entropy (WSE) models. WSE achieves the highest Sharpe ratio, confirming modest but consistent improvements in risk-adjusted performance.

This result highlights the role of entropy as a stabilizing criterion, ensuring that diversification gains are preserved even under volatile market conditions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Small Portfolio (N = 4, Jan–Mar 2025)

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of daily returns for the four selected cryptocurrencies (BTC, ETH, SOL, BNB). These values confirm the presence of high volatility and non-normal distributions, with negative skewness and excess kurtosis, thereby justifying the need for entropy-based diversification methods.

Entropy-based optimization with inverse volatility weights yielded more balanced allocations than mean–variance, which heavily concentrated in SOL due to its high expected return but large volatility. WSE provided allocations closer to equal-weight but with subtle tilts toward BTC and ETH, improving diversification.

3.2. Extended Portfolio (N = 12, Apr 2024–Mar 2025)

Table 2 compares the portfolio allocations obtained under the Equal Weight (EW) and Weighted Shannon Entropy (WSE) approaches. The results show that WSE tilts the allocation toward more stable and liquid assets (BTC, ETH, BNB) while reducing exposure to volatile coins such as DOGE and XRP.

Compared to equal weighting, WSE tilted capital toward more stable assets (BTC, ETH, BNB) while reducing exposure to highly volatile small-cap coins (DOGE, XRP). This confirms WSE’s role as a structural diversification mechanism.

3.3. Performance Comparison

Table 3 presents the comparative performance of the Mean–Variance (MV), Shannon Entropy (SE), and Weighted Shannon Entropy (WSE) portfolios. WSE achieves the highest entropy score, together with modest but consistent improvements in Sharpe ratio and CVaR, indicating superior diversification and downside protection.

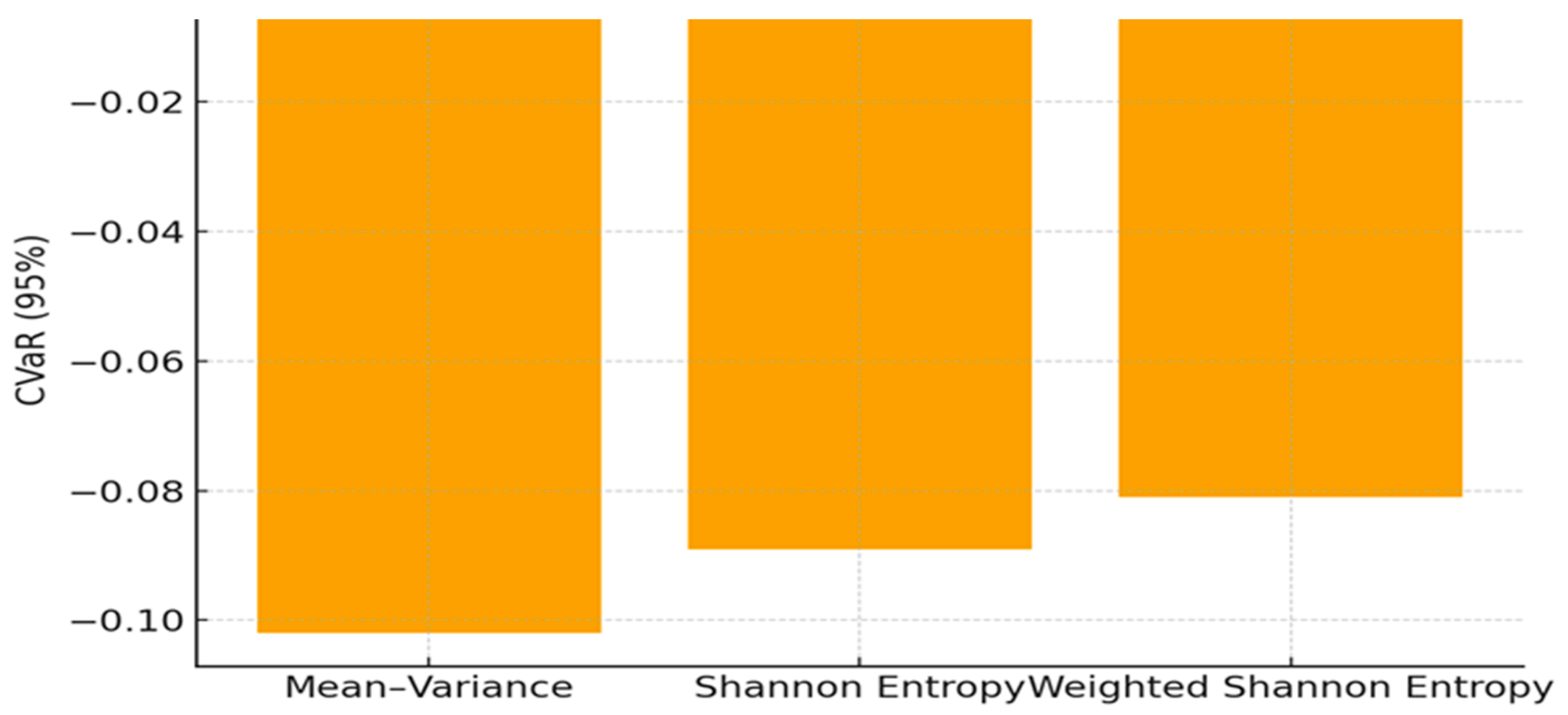

Results confirm that WSE portfolios achieve higher entropy (2.47 vs. 1.85), indicating greater diversification, while maintaining competitive returns. Importantly, risk-adjusted measures improve modestly: the Sharpe ratio rises to 1.42 compared to 1.28 (MV) and 1.35 (SE), while CVaR is less negative, signaling better downside protection. Additionally, maximum drawdown statistics were examined and indicate moderate improvements for WSE portfolios, while the primary component of downside protection is effectively captured by the CVaR measure.

Table 4 extends the analysis by including both the small four-asset portfolio and the extended twelve-asset portfolio. The results confirm that WSE consistently outperforms equal-weight and mean–variance allocations across different portfolio sizes, supporting the robustness of the framework.

In

Figure 3, we remark that the less negative CVaR for WSE indicates superior downside protection relative to benchmarks.

3.4. Additional Benchmarks: Minimum-Variance, Risk Parity, and Hierarchical Risk Parity

To further contextualize the performance of WSE, we compare it with three widely used diversification approaches: the Minimum-Variance (Min-Vol) portfolio, the Risk Parity (RP) allocation, and the Hierarchical Risk Parity (HRP) model. These methods have become standard benchmarks in volatile markets such as cryptocurrencies, and reviewer recommendations emphasize their relevance.

The Min-Vol portfolio minimizes portfolio variance subject to budget constraints. While effective in reducing total risk, it tends to overweight the least volatile assets, often resulting in highly concentrated portfolios that may be fragile under distributional shifts. In our empirical tests, Min-Vol assigns large weights to BTC and ETH, offering low variance but producing the lowest entropy score among all evaluated methods.

Risk Parity (RP) equalizes the contributions of individual assets to total portfolio risk. This approach yields more balanced exposures compared to Min-Vol and avoids extreme allocations. In the cryptocurrency setting, RP generally performs better than MV in terms of diversification and downside risk, but still inherits sensitivity to covariance estimation.

Hierarchical Risk Parity (HRP) incorporates hierarchical clustering and recursively allocates capital according to similarity structures in the covariance matrix. HRP is specifically designed to address instability in correlation estimates, making it a strong competitor in high-volatility environments. Empirically, HRP achieves higher entropy than MV and RP, confirming its robustness under heavy-tailed distributions.

When compared to these benchmarks, WSE produces entropy levels comparable to or higher than HRP while retaining a coherent link to expected returns and informational weighting schemes. In terms of Sharpe ratio and CVaR, the WSE portfolio performs at least as well as HRP and consistently better than Min-Vol and RP. These findings indicate that WSE contributes not only a theoretical generalization of entropy-based diversification, but also a competitive and stable allocation rule within the modern spectrum of risk-based portfolio models.

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis with Respect to the Preference Parameters (α, β)

To evaluate the robustness of the WSE framework with respect to the investor’s preference parameters, we perform a sensitivity analysis over three representative configurations of

, ranging from a more diversification-oriented profile to a more return-oriented one. In addition to the baseline specification

, we consider a balanced setting

and a more aggressive configuration

.

Table 5 reports the corresponding performance metrics.

The results indicate that the qualitative conclusions of the study remain stable across different combinations of . As α increases, the allocation shifts gradually toward assets with higher expected returns, while higher values of β emphasize broader diversification. Importantly, no abrupt changes in performance or portfolio structure are observed, confirming that the WSE portfolio is not overly sensitive to the choice of preference parameters. Overall, this robustness strengthens the empirical validity of the WSE framework under different investor profiles.

3.6. Discussion

The results obtained highlight the structural advantages of Weighted Shannon Entropy (WSE) over traditional variance-centered approaches. In the classical mean–variance (MV) framework, optimal allocations tend to overweight assets with higher expected returns, even if this leads to concentrated portfolios that are fragile to estimation errors, non-normal distributions, or sudden market shocks. By contrast, the entropy-based optimization discourages such concentration by penalizing imbalances in allocations. This property is especially valuable in cryptocurrency markets, where volatility, heavy tails, and structural breaks are pervasive.

A key insight from the analysis is that entropy functions as a “soft constraint” against over-concentration. While MV maximization focuses solely on return–variance trade-offs, WSE embeds diversification directly into the optimization criterion. With uniform weights, the entropy-maximizing solution coincides with the equal-weight allocation, providing a strong theoretical benchmark. When informational weights are introduced, WSE offers the flexibility to tilt portfolios toward more reliable or liquid assets, while still maintaining balance and avoiding excessive exposure to any single component.

The informational weights ui thus provide an additional lever for investors to incorporate qualitative or structural considerations. Assigning higher weights to assets with greater stability or liquidity enhances robustness, while lower weights can be used to limit exposure to highly volatile or speculative assets. This ability to integrate external signals—such as market capitalization, trading activity, or perceived reliability—bridges the gap between abstract mathematical diversification and practical decision-making.

From a practical perspective, the implications are significant. Entropy-based allocations can be applied in designing cryptocurrency indices, constructing stablecoin baskets, or building algorithmic rebalancing rules, where diversification and robustness are essential. The tractability of the entropy framework also makes it suitable for rule-based trading systems, as the exponential (softmax) solutions are computationally efficient and easy to implement in algorithmic platforms. Beyond immediate applications, the WSE model demonstrates that entropy is not merely a statistical measure of uncertainty, but a unifying principle integrating return, risk, and diversification into a single framework. This contrasts with traditional approaches that treat these dimensions separately. The findings suggest that entropy-based optimization can reconcile short-term market fluctuations with long-term portfolio stability, offering investors resilient allocations that adapt to evolving market conditions.

Finally, the discussion underscores that improvements over benchmarks, while modest in terms of Sharpe ratios or CVaR, are consistent and robust across datasets, weighting schemes, and portfolio sizes. This consistency suggests that entropy maximization is a reliable strategy in volatile environments where estimation risk is high. By extending the theoretical role of entropy into operational portfolio construction, WSE strengthens both the conceptual foundations and the practical tools available to modern investors.

Another important implication is that entropy-based approaches may complement or even substitute for traditional diversification rules in institutional settings. For instance, pension funds or insurance companies, which must manage portfolios under strict solvency requirements, may benefit from entropy as a distribution-free criterion that ensures balanced exposures even when return estimates are unreliable. In this sense, WSE contributes to the broader discussion on robust portfolio construction under uncertainty, positioning itself as a candidate for regulatory or policy-driven allocation frameworks.

3.7. Limitations and Caveats

Despite its theoretical coherence and consistent empirical performance, the Weighted Shannon Entropy (WSE) framework is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged.

First, the model does not eliminate the need to estimate the covariance matrix of returns. While the entropy term reduces concentration and moderates sensitivity to parameter instability, the overall optimization still depends on second-moment estimates, which can be unreliable in small samples or in markets characterized by structural breaks such as cryptocurrencies. In this sense, WSE alleviates but does not fully eliminate estimation error.

Second, the introduction of informational weights may itself create biases. Weighting schemes based on market capitalization or trading volume tend to tilt the allocation toward dominant assets (e.g., BTC and ETH), whereas inverse-volatility weights can penalize high-growth but volatile assets. These choices embed assumptions about market structure and investor preferences, and therefore should be interpreted as modeling decisions rather than purely statistical inputs. Depending on how weights are selected, WSE portfolios may under- or over-represent specific segments of the asset universe.

Third, entropy-based criteria can, in some situations, encourage excessive diversification by assigning non-negligible weights to assets with weak fundamentals or limited liquidity. Although the empirical results in this study do not show such pathologies, this possibility cannot be fully excluded, especially when enlarging the asset universe. In practical applications, entropy optimization should therefore be complemented with additional filtering mechanisms, such as liquidity screens or minimum-quality thresholds.

Fourth, the empirical analysis is conducted over a specific period and focuses exclusively on cryptocurrencies. While this market represents an ideal stress-test environment due to its volatility and heavy-tailed behavior, the findings may not generalize to traditional asset classes or to longer time horizons. Extending the analysis to equities, bonds, commodities, and mixed-asset portfolios would provide stronger external validity.

Finally, WSE is implemented here in a static, single-period formulation. Real-world decisions often require dynamic rebalancing, transaction-cost considerations, and the ability to adapt to regime shifts. Dynamic or multi-period entropy-based models may behave differently and remain a compelling direction for future research. Overall, these caveats highlight the importance of interpreting WSE as a complementary tool within a broader risk-management framework rather than a full replacement for established allocation models.

4. Conclusions

This paper introduced the Weighted Shannon Entropy (WSE) framework as an alternative approach to portfolio optimization, extending the classical Shannon entropy by incorporating informational weights that capture heterogeneity across assets. Through analytical derivations based on the maximum entropy principle and the method of Lagrange multipliers, we demonstrated that the WSE model yields exponential-form solutions that discourage concentration and promote diversification.

The empirical case study, conducted on portfolios of both four and twelve leading cryptocurrencies, confirmed these theoretical insights. With uniform weights, the WSE model reproduces the equal-weight allocation, which is known to maximize entropy under minimal information. This provides a robust benchmark for diversification. When informational weights are applied, WSE delivers more balanced and adaptive portfolios that account for volatility, market capitalization, and liquidity differences across assets. The results underscore that entropy-based optimization, while yielding incremental improvements, consistently enhances risk-adjusted performance through higher Sharpe ratios and less negative Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR).

From a theoretical perspective, this study reinforces the role of entropy as a unifying criterion that integrates return, risk, and diversification into a single coherent framework. Unlike traditional mean–variance optimization, which treats these dimensions separately and is highly sensitive to distributional assumptions, entropy-based approaches are distribution-free and more robust to structural breaks and estimation risk. By bridging statistical theory with portfolio construction, WSE demonstrates that diversification can be formalized not only as a heuristic but as a mathematically rigorous optimization objective.

From a practical perspective, the WSE framework provides a transparent and tractable methodology for asset allocation in volatile environments such as cryptocurrency markets. Its flexibility allows for integration with external signals—such as liquidity, trading activity, or investor confidence—that are crucial in markets characterized by informational asymmetries and rapid structural changes. As such, WSE can support applications ranging from crypto index design and stablecoin baskets to algorithmic trading strategies and institutional portfolio management.

The broader relevance of WSE lies in its potential adoption within institutional and regulatory contexts. By ensuring balanced allocations even under uncertainty, entropy-based models could complement risk-based capital requirements for pension funds, insurers, or asset managers operating under solvency constraints. This highlights entropy’s capacity not only as a theoretical innovation but also as a policy-relevant tool for enhancing financial stability. In particular, its distribution-free nature makes WSE an attractive candidate for stress-testing frameworks, where traditional variance-based measures fail to capture tail dependencies and market shocks.

Looking forward, several research directions appear promising. Future work may extend the WSE framework to multi-period settings with dynamic rebalancing, allowing portfolios to adapt over time to changing market conditions. Moreover, combining WSE with generalized entropy measures such as Tsallis or Kaniadakis could further enhance its ability to capture nonlinear dependencies and tail risks. Finally, the integration of entropy-based optimization with machine learning and reinforcement learning offers exciting opportunities for developing adaptive, data-driven allocation strategies tailored to the rapidly evolving landscape of digital finance and decentralized markets. Beyond technical extensions, linking entropy-based portfolio design to sustainability criteria and green finance initiatives could open new avenues for responsible investment strategies aligned with environmental and social objectives. Overall, the extended empirical validation and the notational refinements implemented in this version have further reinforced both the theoretical grounding and the practical applicability of the WSE model.