SHAP Stability in Credit Risk Management: A Case Study in Credit Card Default Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

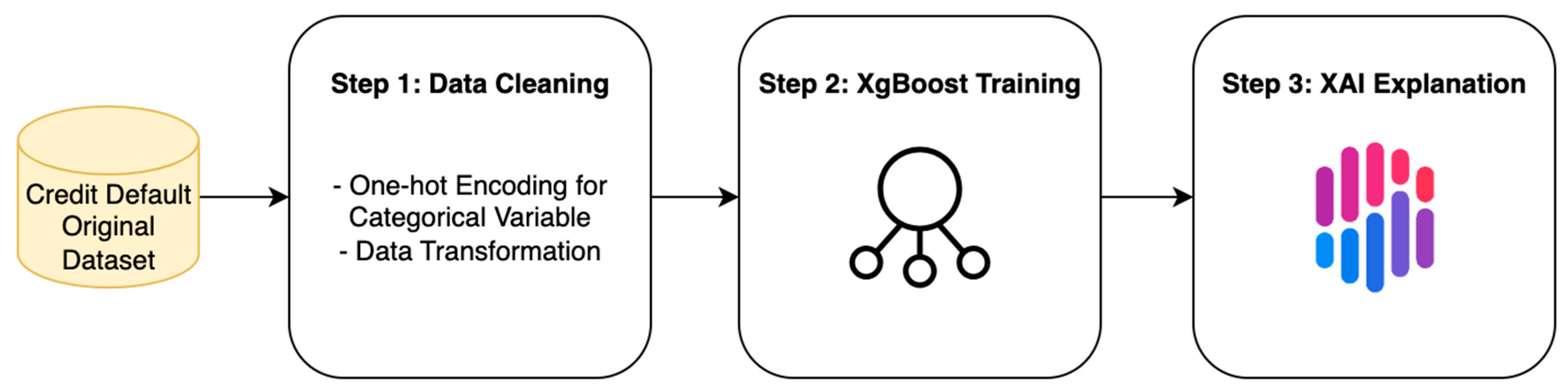

3. Methodology

- -

- Step 1 Data Source and Cleaning: We employ the Default of Credit Card Clients dataset from the Machine Learning Repository of University of California, Irvine (UCI), which contains 30,000 credit card accounts in Taiwan (Yeh 2009). The data are cleaned and pre-processed through exploratory analysis, variable selection, and variable transformation to ensure feature quality.

- -

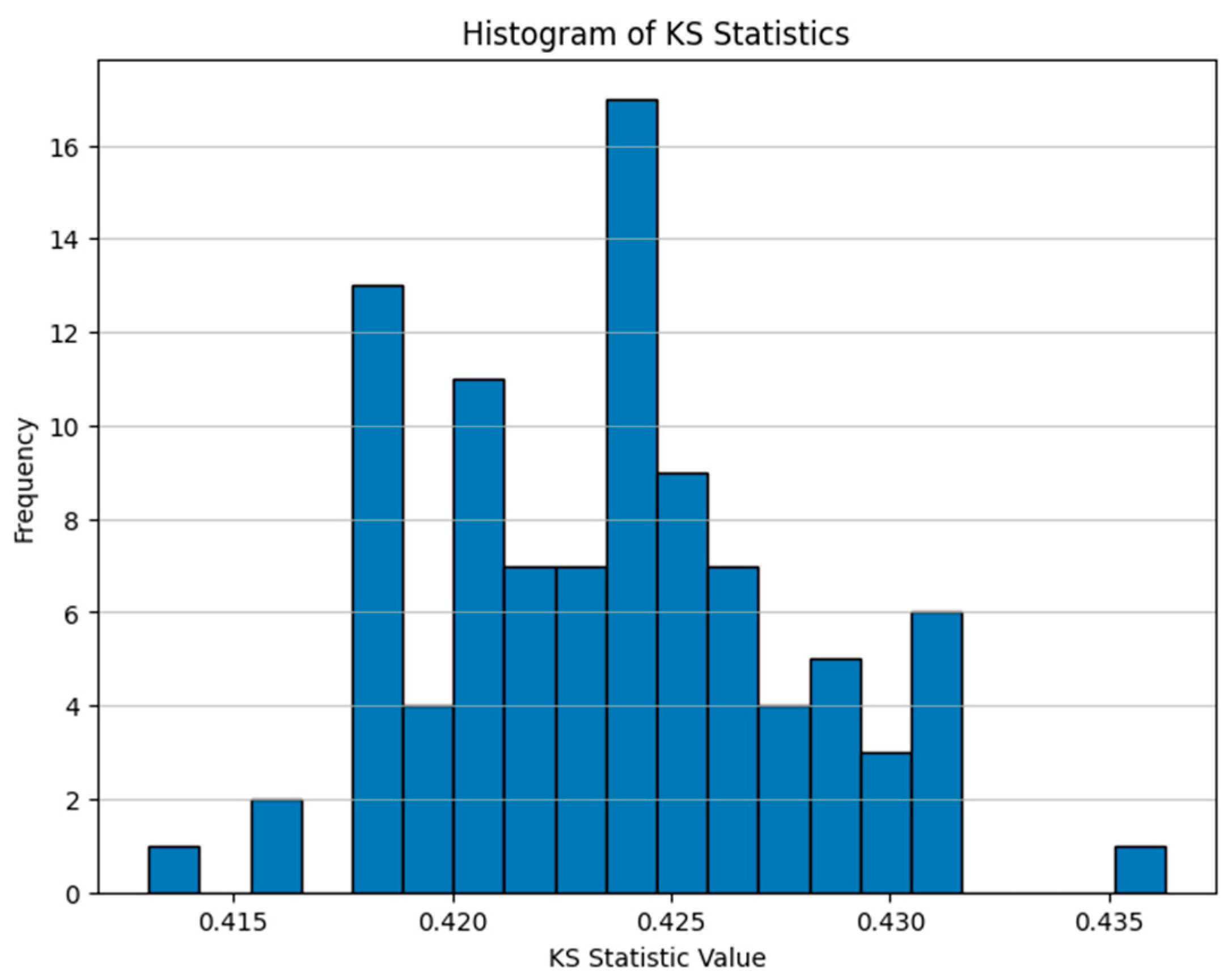

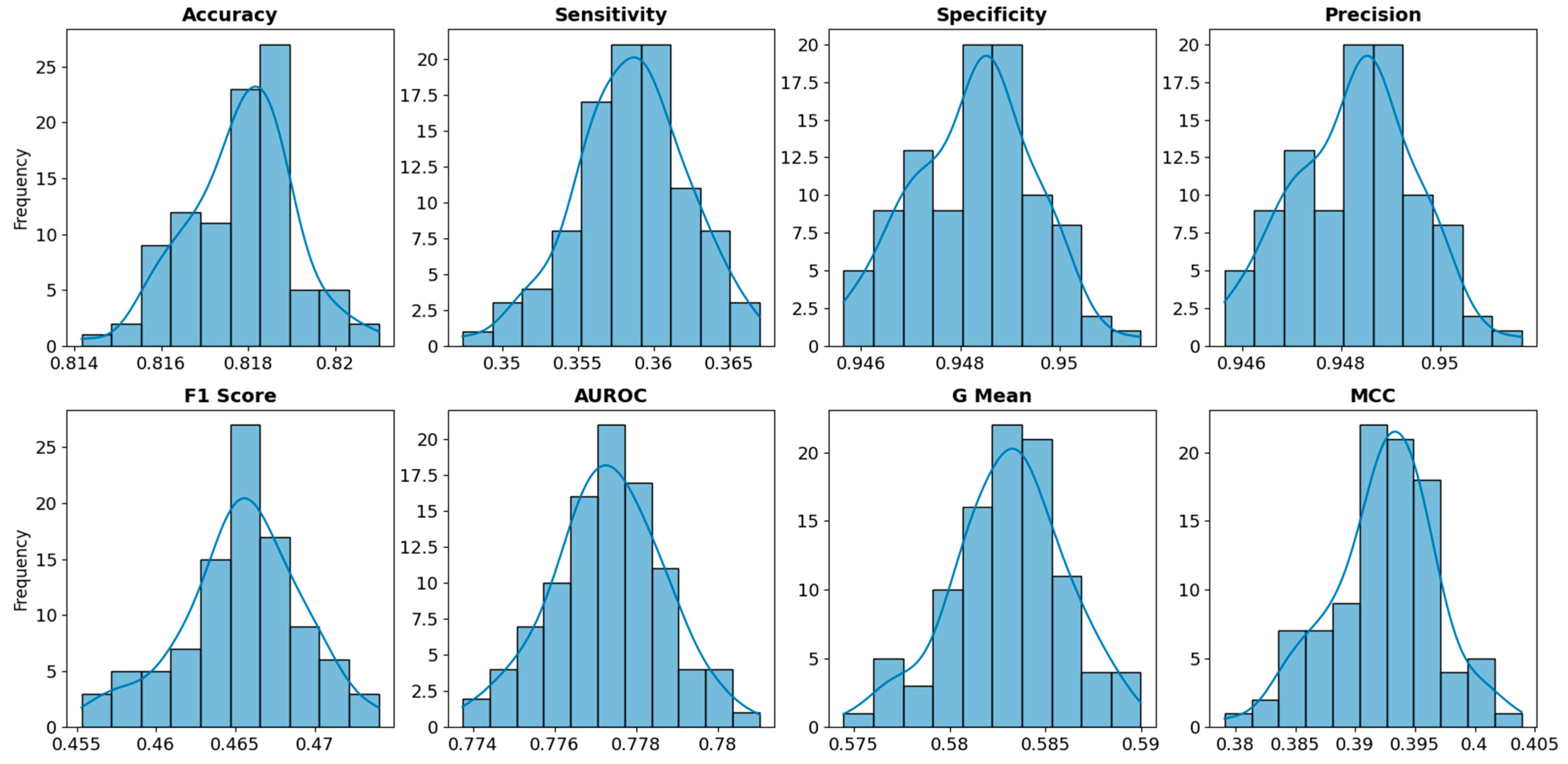

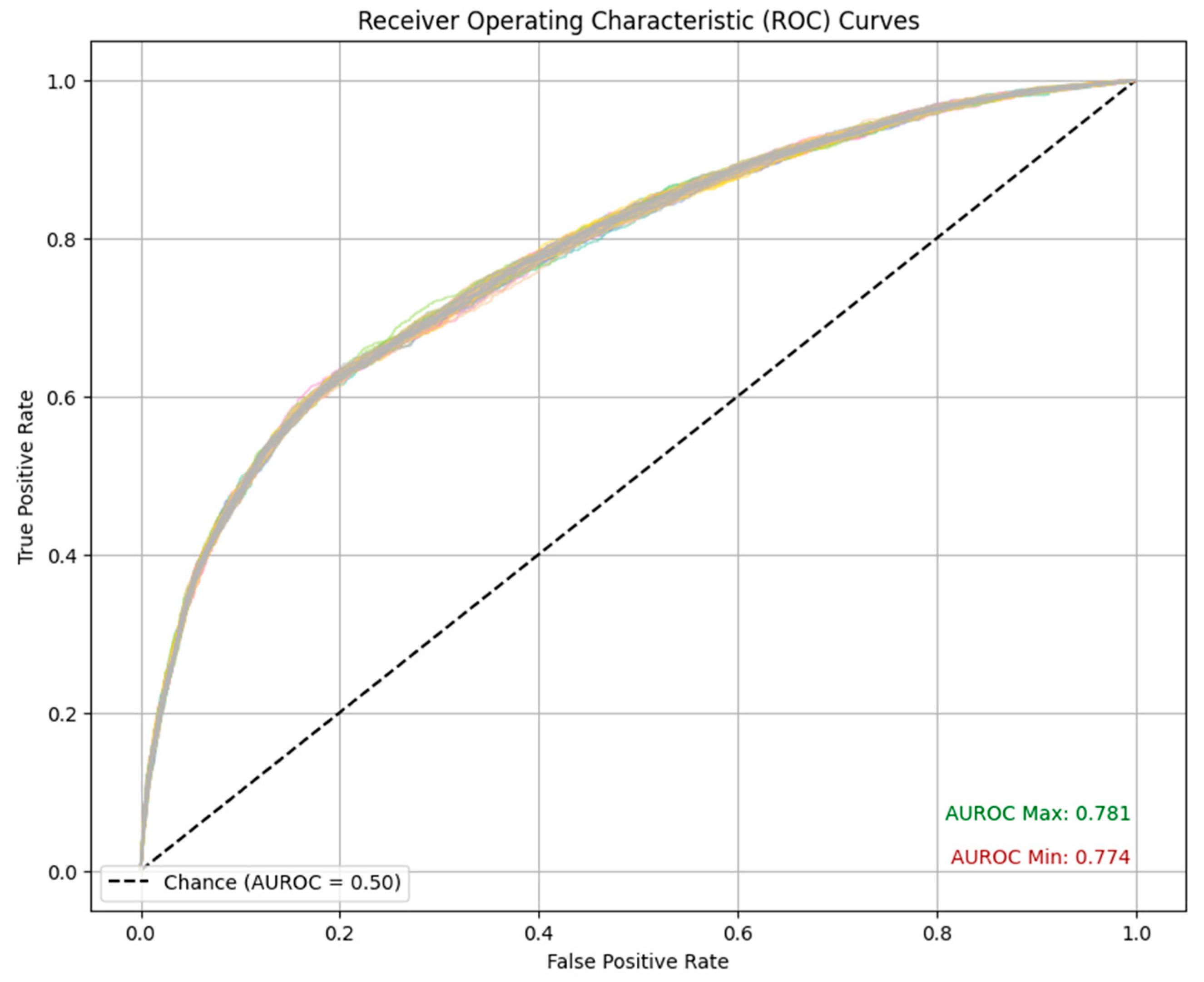

- Step 2 XGBoost Training: We construct a probability-of-default model using the XGBoost algorithm. We train 100 models with identical hyperparameters but different random seeds, thereby generating multiple independent models for subsequent SHAP stability analysis. We evaluate model performance using common performance metrics, including Accuracy, F1-score, Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) Statistic, and AUROC.

- -

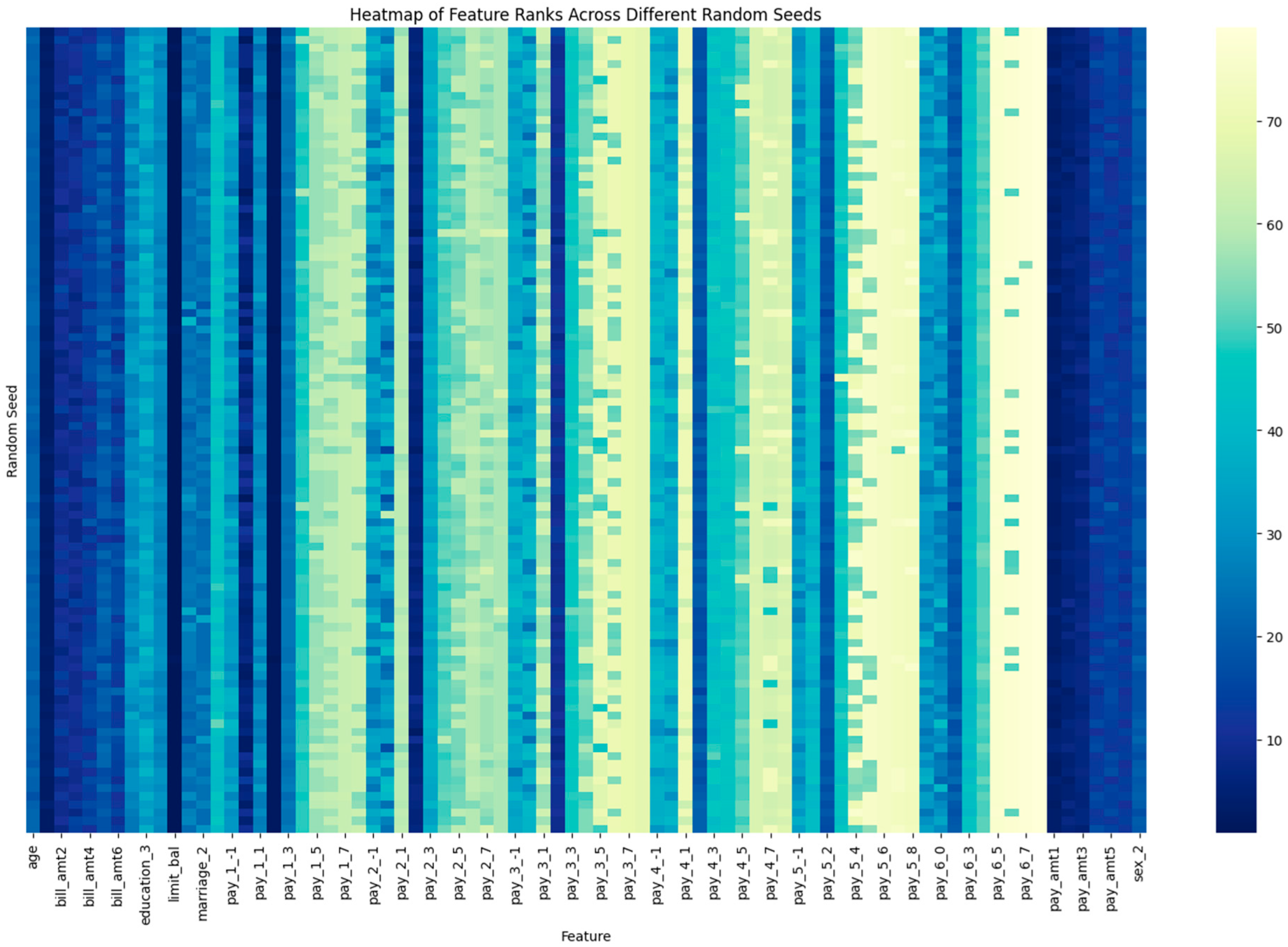

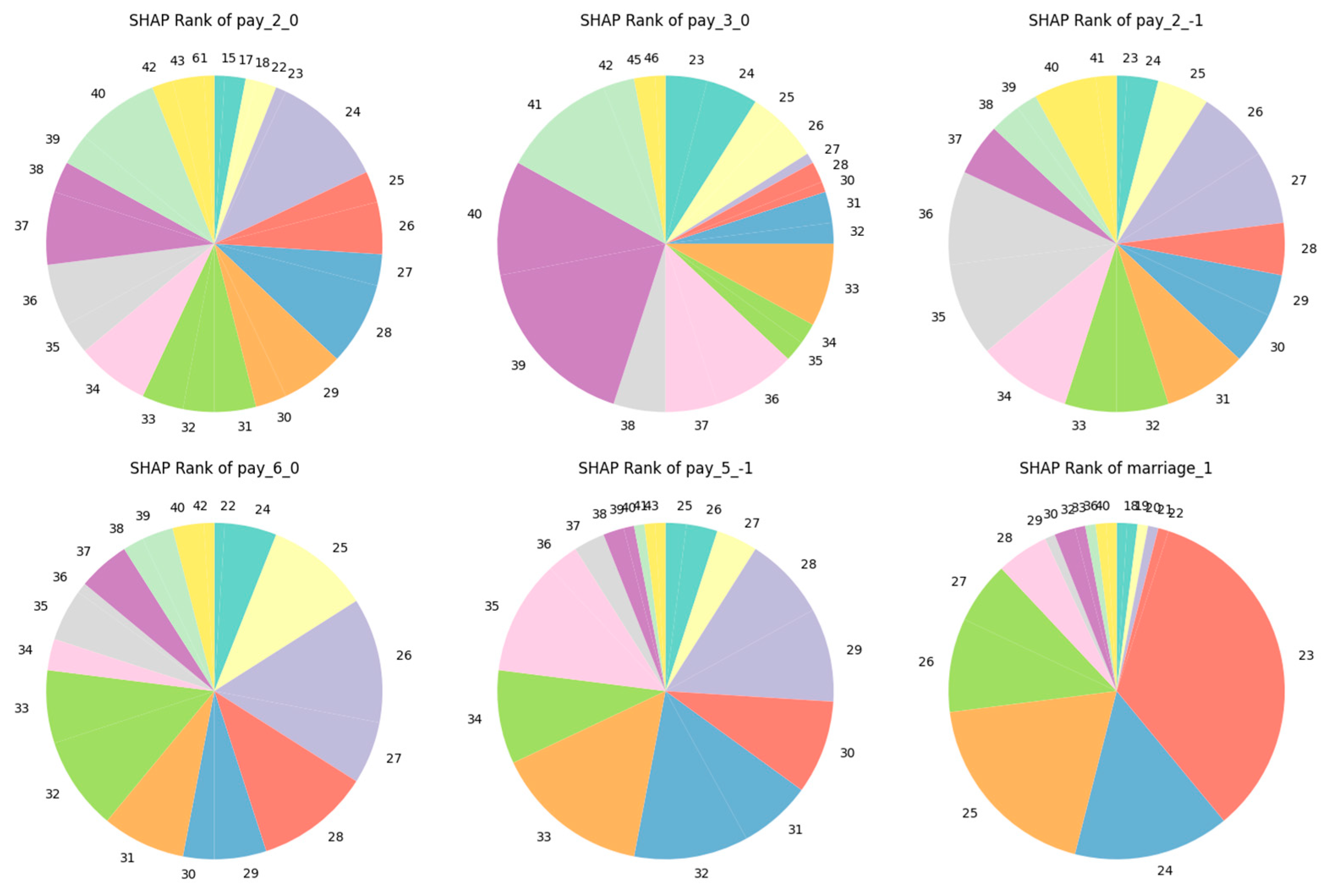

- Step 3 XAI Explanation: In the final stage, we calculate and evaluate the SHAP values for all trained models to obtain global feature explanations. The analysis examines the stability of SHAP feature-importance rankings across models, quantified using the Kendall’s W statistics as a measure of ranking stability.

3.1. Data Structure and Cleaning

3.2. Model Development

3.3. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Evaluation

- is the number of features being ranked

- is the number of ranking lists, which is the number of models in this study

- where is the sum of ranks for feature across all models and is the average of all

4. Results

4.1. Performance Evaluation

4.2. Global SHAP Evaluation

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alonso, Andrés, and Jose Manuel Carbo. 2020. Machine Learning in Credit Risk: Measuring the Dilemma Between Prediction and Supervisory Cost. Banco de Espana Working Paper No. 2032. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3724374 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Baesens, Bart, Tony Van Gestel, Stijn Viaene, Maria Stepanova, Johan Suykens, and Jan Vanthienen. 2003. Benchmarking State-of-the-Art Classification Algorithms for Credit Scoring. Journal of the Operational Research Society 54: 627–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballegeer, Matteo, Matthias Bogaert, and Dries F. Benoit. 2025. Evaluating the Stability of Model Explanations in Instance-Dependent Cost-Sensitive Credit Scoring. European Journal of Operational Research 326: 630–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandary, Rakshith, and Bidyut Kumar Ghosh. 2025. Credit Card Default Prediction: An Empirical Analysis on Predictive Performance Using Statistical and Machine Learning Methods. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2011. Supervisory Guidance on Model Risk Management (SR 11-7); Washington, DC: Federal Reserve and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/sr1107.htm (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Bolton, Christine. 2009. Logistic Regression and Its Application in Credit Scoring. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/134cf4372fbb2bc5b6f9cbda4c559337/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Boser, Bernhard E., Isabelle M. Guyon, and Vladimir N. Vapnik. 1992. A Training Algorithm for Optimal Margin Classifiers. Paper presented at Fifth Annual Workshop on Computational Learning Theory, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, July 27–29; pp. 144–52. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, Leo. 2001. Random Forests. Machine Learning 45: 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussmann, Niklas, Paolo Giudici, Dimitri Marinelli, and Jochen Papenbrock. 2021. Explainable Machine Learning in Credit Risk Management. Computational Economics 57: 203–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelvecchi, Davide. 2016. Can We Open the Black Box of AI? News Feature. Nature News 538: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Tianqi, and Carlos Guestrin. 2016. Xgboost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. Paper presented at 22nd Acm Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, August 13–17; pp. 785–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yujia, Raffaella Calabrese, and Belen Martin-Barragan. 2024. Interpretable Machine Learning for Imbalanced Credit Scoring Datasets. European Journal of Operational Research 312: 357–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. 2022. Consumer Financial Protection Circular 2022-03: Adverse Action Notification Requirements in Connection with Credit Decisions Based on Complex Algorithms. June. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2022-06-14/pdf/2022-12729.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. 2023. The Consumer Credit Card Market Report, 2023; Washington, DC: Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/11/02/2023-24132/consumer-credit-card-market-report-2023 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Černevičienė, Jurgita, and Audrius Kabašinskas. 2024. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in Finance: A Systematic Literature Review. Artificial Intelligence Review 57: 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Rudresh, Devam Dave, Het Naik, Smiti Singhal, Rana Omer, Pankesh Patel, Bin Qian, Zhenyu Wen, Tejal Shah, Graham Morgan, and et al. 2023. Explainable AI (XAI): Core Ideas, Techniques, and Solutions. ACM Computing Surveys 55: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equal Credit Opportunity Act. 2024. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/statutes/equal-credit-opportunity-act (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Fair Credit Reporting Act. 2023. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/fcra-may2023-508.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Friedman, Jerome H. 2001. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Annals of Statistics 29: 1189–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Géron, Aurélien. 2022. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow. Sebastopol: O’Reilly Media, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Nikhil. 2025. Explainable AI for Regulatory Compliance in Financial and Healthcare Sectors: A Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Advances in Engineering and Management 7: 489–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, David J., and William E. Henley. 1997. Statistical Classification Methods in Consumer Credit Scoring: A Review. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 160: 523–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlongwane, Rivalani, Kutlwano Ramabao, and Wilson Mongwe. 2024. A Novel Framework for Enhancing Transparency in Credit Scoring: Leveraging Shapley Values for Interpretable Credit Scorecards. PLoS ONE 19: e0308718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Financial Reportings Standard 9 Financial Instruments. 2019. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/publications/pdf-standards/english/2022/issued/part-a/ifrs-9-financial-instruments.pdf?bypass=on (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Kendall, Maurice G., and B. Babington Smith. 1939. The Problem of m Rankings. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 10: 275–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, Max, and Kjell Johnson. 2013. Applied Predictive Modeling. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lessmann, Stefan, Bart Baesens, Hsin-Vonn Seow, and Lyn C. Thomas. 2015. Benchmarking State-of-the-Art Classification Algorithms for Credit Scoring: An Update of Research. European Journal of Operational Research 247: 124–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Mingxuan, Yilin Ning, Han Yuan, Marcus Eng Hock Ong, and Nan Liu. 2022. Balanced Background and Explanation Data Are Needed in Explaining Deep Learning Models with SHAP: An Empirical Study on Clinical Decision Making. arXiv arXiv:2206.04050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, Scott M., and Su-In Lee. 2017. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: 4768–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misheva, Branka Hadji, Joerg Osterrieder, Ali Hirsa, Onkar Kulkarni, and Stephen Fung Lin. 2021. Explainable AI in Credit Risk Management. arXiv arXiv:2103.00949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, Christoph. 2019. Interpretable Machine Learning. Available online: https://www.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=jBm3DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Molnar,+Christoph.+2019.+Interpretable+Machine+Learning.&ots=EhxTUnJEQ1&sig=d3rIDzBa22-dd92ObB6D1LqI340 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Montevechi, André Aoun, Rafael De Carvalho Miranda, André Luiz Medeiros, and José Arnaldo Barra Montevechi. 2024. Advancing Credit Risk Modelling with Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Review of the State-of-the-Art. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 137: 109082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mvula Chijoriga, Marcellina. 2011. Application of Multiple Discriminant Analysis (MDA) as a Credit Scoring and Risk Assessment Model. International Journal of Emerging Markets 6: 132–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonakis, John, and George Diacogiannis. 2010. Evaluating the Likelihood of Using Linear Discriminant Analysis as A Commercial Bank Card Owners Credit Scoring Model. International Business Research 3: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Didrik. 2016. Tree Boosting with Xgboost-Why Does Xgboost Win” Every” Machine Learning Competition? Master’s thesis, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Cruz, Fernando, Jermy Prenio, Fernando Restoy, and Jeffery Yong. 2025. Managing Explanations: How Regulators Can Address AI Explainability. Available online: https://www.fiduciacorp.com/s/BIS-Mangaing-AI-Expectations.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ribeiro, Marco Tulio, Sameer Singh, and Carlos Guestrin. 2016. ‘Why Should I Trust You?’: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. arXiv arXiv:1602.04938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, Cynthia. 2019. Stop Explaining Black Box Machine Learning Models for High Stakes Decisions and Use Interpretable Models Instead. Nature Machine Intelligence 1: 206–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott Lundberg. 2025. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) Documentation. Available online: https://shap.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Shukla, Deepa. 2024. A Survey of Machine Learning Algorithms in Credit Risk Assessment. Journal of Electrical Systems 20: 6290–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, Naeem. 2012. Credit Risk Scorecards: Developing and Implementing Intelligent Credit Scoring. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Suhadolnik, Nicolas, Jo Ueyama, and Sergio Da Silva. 2023. Machine Learning for Enhanced Credit Risk Assessment: An Empirical Approach. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16: 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supervision, Banking. 2011. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management and Supervision (September 2008). Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/45696423/bcbs213.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Thomas, Lyn C., David B. Edelman, and Jonathan N. Crook. 2002. Credit Scoring and Its Applications. Philadelphia: SIAM. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Patrick, K. Valerie Carl, and Oliver Hinz. 2024. Applications of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Finance—Traditional statistical approaches Systematic Review of Finance, Information Systems, and Computer Science Literature. Management Review Quarterly 74: 867–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xgboost 3.1.1. 2025. Available online: https://xgboost.readthedocs.io/en/stable/tutorials/feature_interaction_constraint.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Yeh, I-Cheng. 2009. Default of Credit Card Clients. Irvine: UCI Machine Learning Repository. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Wei Jie, Wihan Van Der Heever, Rui Mao, Erik Cambria, Ranjan Satapathy, and Gianmarco Mengaldo. 2025. A Comprehensive Review on Financial Explainable AI. Artificial Intelligence Review 58: 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Description | Data Type | Data Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| id | Unique ID for Each Client | String | Not applicable |

| limit_bal | Amount of credit given in New Taiwan (NT) dollars (includes individual and family/supplementary credit | Numeric | 10,000 to 1,000,000 |

| sex | Gender (1 = male, 2 = female) | Category | 1 or 2 |

| education | Education Level (0 = others, 1 = graduate school, 2 = university, 3 = high school, 4 = others, 5 = unknown, 6 = unknown) | Category | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

| marriage | Marital status (0 = others, 1 = married, 2 = single, 3 = others) | Category | 0, 1, 2, 3 |

| age | Age in years | Numeric | 21 to 79 |

| pay_1-pay_6 | Repayment status in each month from April to September 2005 (−2 = No Consumption, −1 = pay duly, 0 = The use of revolving credit 1 = payment delay for one month, 2 = payment delay for two months, … 8 = payment delay for eight months, 9 = payment delay for nine months and above) | Category | −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

| bill_amt1-bill_amt6 | Amount of bill statement each month from April to September 2005 (NT dollar) | Numeric | from −339,603 to 1,664,089 |

| pay_amt1-pay_amt6 | The amount of previous payment in each month from April to September 2005 (NT dollar) | Numeric | from 0 to 1,684,259 |

| default.payment.next.month | Default payment (1 = yes, 0 = no) | Binary | 0, 1 |

| Predictions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (Bad/Event) | Negative (Not Bad/Non-Event) | Metrics | ||

| Actuals | Positive (Bad/Event) | True Positive (TP) | False Negative (FN) | Recall (True Positive Rate) = TP/(TP + FN) |

| Negative (Not Bad/Non-Event) | False Positive (FP) | True Negative (TN) | False Positive Rate = FP/(FP + TN) | |

| Metrics | Precision = TP/(TP + FP) | Negative predictive value = TN/(TN + FN) | F-score = 2 × Recall × Precision/(Recall + Precision) | |

| Metric | Median | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 79.53% | 79.25% | 79.77% |

| Sensitivity | 53.73% | 53.08% | 54.26% |

| Specificity | 86.86% | 86.68% | 87.01% |

| Precision | 86.86% | 86.68% | 87.01% |

| F1 Score | 53.73% | 53.08% | 54.26% |

| AUROC | 77.73% | 77.46% | 78.00% |

| G Mean | 68.32% | 67.83% | 68.71% |

| MCC | 40.59% | 39.76% | 41.27% |

| Variable | Meaning | Rank | Frequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit_bal | Amount of credit given in NT dollars (includes individual and family/supplementary credit | 1 | 96 |

| 2 | 4 | ||

| pay_1_2 | Repayment status in September 2005: Payment delay for two months | 1 | 4 |

| 2 | 93 | ||

| 3 | 3 | ||

| bill_amt1 | Amount of bill statement in September 2005 (NT dollar) | 3 | 56 |

| 4 | 39 | ||

| 5 | 5 | ||

| pay_amt1 | Amount of previous payment in September 2005 (NT dollar) | 3 | 29 |

| 4 | 49 | ||

| 5 | 17 | ||

| 6 | 3 | ||

| 7 | 2 | ||

| pay_amt2 | Amount of previous payment in August 2005 (NT dollar) | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | 46 | ||

| 6 | 25 | ||

| 7 | 16 | ||

| 8 | 7 | ||

| 9 | 1 |

| Variable | Meaning | Rank | Frequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| pay_5_7 | Repayment status in May 2005: Payment delay for seven months | 50 | 1 |

| 73 | 85 | ||

| 75 | 14 | ||

| pay_5_6 | Repayment status in May 2005: Payment delay for six months | 73 | 1 |

| 74 | 99 | ||

| pay_6_5 | Repayment status in April 2005: Payment delay for five months | 76 | 81 |

| 77 | 19 | ||

| pay_6_7 | Repayment status in April 2005: Payment delay for seven months | 54 | 1 |

| 78 | 99 | ||

| pay_6_8 | Repayment status in April 2005: Payment delay for eight months | 79 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, L.; Wang, Y. SHAP Stability in Credit Risk Management: A Case Study in Credit Card Default Model. Risks 2025, 13, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13120238

Lin L, Wang Y. SHAP Stability in Credit Risk Management: A Case Study in Credit Card Default Model. Risks. 2025; 13(12):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13120238

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Luyun, and Yiqing Wang. 2025. "SHAP Stability in Credit Risk Management: A Case Study in Credit Card Default Model" Risks 13, no. 12: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13120238

APA StyleLin, L., & Wang, Y. (2025). SHAP Stability in Credit Risk Management: A Case Study in Credit Card Default Model. Risks, 13(12), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13120238