1. Introduction

Many have commented on the stalled life expectancy in the UK and rightly asked why this has occurred and who and what is responsible, e.g.,

Raleigh (

2024);

Alexiou et al. (

2021);

Marshall et al. (

2019). Recent changes have come after six decades of almost continuous improvement in life expectancy, with the UK being worse affected than most comparable countries.

Why is this important? Life expectancy has been subject to shocks since 2010, which have been blamed for the decline, most recently the COVID-19 pandemic, which arrived in the UK in January 2020. The possible role of the period of financial austerity after the financial crisis of 2008 is hotly debated. This coincided with cuts in social programmes and public services failing to keep pace with demand (e.g., see

Stuckler et al. 2017;

Walsh et al. 2022).

The deeper question is why decades of improvement have come to a halt, and what would have happened if austerity and COVID had not occurred. If stalling life expectancy is more than just a temporary blip, to what extent is it threatening people’s health and livelihoods and the economy in general (

Mayhew and Burrows 2023)? Would, for example, fewer have died in the pandemic had the UK been healthier, as the

BMA (

2022) has argued?

It is important, therefore, to examine how health varies with life expectancy. Intuitively, a longer life correlates with longer years in good health, but the correlation is not set in concrete. People can live long lives but spend many years in poor health prior to death, suggesting that healthcare systems prolong life more effectively than they prolong health, with the result that when life expectancy suffers, health suffers more.

If this is the case, the effect of additional years spent in ill health will adversely impact the ability to work, depending on the individual, and quite often long before a person reaches state pension age. It will further affect public and intergenerational transfers between households and individuals in the form of higher taxes and healthcare and welfare costs—leading to declines in living standards.

Such differences are socially patterned, with richer, more educated people doing better; this, in turn, manifests in spatial inequalities depending on where they live. Exposure to factors responsible for poor health accrues over the life cycle, but the negative health effects of adverse lifestyles appear before middle age (

Green et al. 2021). It does not help that the population is also ageing rapidly, which is itself a risk factor and so gives more urgency to the problem.

Life expectancy among earlier cohorts benefited from factors such as the decline of manufacturing and hazardous occupations, such as coal mining, improvement in air quality in urban areas, and better nutrition. It is likely, though, that in post-industrial society the beneficial effects of those changes may, in part at least, have run their course—leading to another change in trajectory.

Aims

The aim of the paper is to show the asymmetrical relationship between health and life expectancy and the social and economic impacts measured in greater social inequalities, and the ruinous burden on healthcare services and public finances. It addresses an unexplored connection between social policy on the one hand and a successful, balanced economy, which is essential for economic growth, but also identifies unresolved policy challenges.

As evidence, we use the novel technique of partial life expectancy to understand which sub-age groups are contributing most to the problem, and the trends within each age interval. This approach allows us to investigate changes in life expectancy at distinct stages of the life cycle and compare whether the UK is better or worse than other countries.

By linking partial life expectancy to health expectancy, we pinpoint how minor changes to life expectancy translate into health and vice versa, and why the geography of deprivation plays a key role. From a social perspective, we show that health inequalities are correlated with higher levels of economic inactivity and why, in some areas, adults quit the workforce years before state pension age.

The first part of the paper considers in detail how life expectancy has stalled—especially among the over 50s, where outcomes between individuals start to diverge as a result. We show that the UK compares unfavourably with other countries and that the long-established pattern of increasing life expectancy since the 1950s, which has been taken for granted, appears to have run out of steam.

Using ONS data (

Office for National Statistics 2022), we show that the variation in health expectancy is greater than the variation in life expectancy at the local level. Specifically, people in the most deprived areas spend longer and a greater proportion of their lives in ill health compared with those living in more affluent areas, resulting in great inequality.

They have higher age-related expenditure on healthcare costs, are more likely to be economically inactive, and are in receipt of welfare benefits. Whilst the years spent in poor health shorten lives, we obtain the important result that a one-year decline in life expectancy equates to an average of 2.37-year loss in health expectancy, which skews public expenditure to the least affluent areas.

We discuss the mechanisms that are driving these trends and what could be done to slow or reverse them. Among these are unhealthy lifestyles, including exposure to smoking, poor diet, excessive drinking, or lack of physical exercise, which are now arguably the main threats to health. For example, smoking, although in decline, is still a major health risk, whilst the prevalence of unhealthy diets is a major cause of obesity, with 30% of UK adults deemed to be obese compared with 20% in 2000 (source WHO, which defines obesity as a person having a Body Mass Index of 30 or above)

1.

We evaluate the effect of poor health on the economy, in three different policy domains—labour markets, health and welfare—touching on related areas of policy including pension age and immigration. But first, we explain how partial life expectancy works before comparing our results with those for other countries with which the UK is often compared.

2. UK Demographic Trends and Partial Life Expectancy

The number of people age 50 and in the UK rose by 18%, from 21.6 m to 25.5 m, in the decade from 2010. This age group now make up 38% of the population, and changes in their health and longevity have an impact on the whole economy. This latest analysis considers the changing life expectancy of UK adults in this group, the scale and range of the economic impact, and what should happen next.

Under age fifty, the mortality experience of younger adults has remained broadly similar. Most deaths occur in middle and older age, so the focus of our attention is those aged 50 and older. As they age, their mortality experience starts to diverge. It means that changes to longevity in this crucial age group matter to the whole economy.

Many in this age group are in poor health, limiting their ability to work, with 34% suffering from long-term illness or disability. These are not temporary changes but part of the longer-term effects of population ageing, which includes declining health and potentially economic stagnation—the impact of which could be lessened with a comprehensive public health strategy.

2.1. Partial Life Expectancy

Although it is widely used as a measure of well-being, there is a problem with just reporting changes in life expectancy. It says nothing about changes in parts of the age structure which could highlight one or more concerns, or, from a policy standpoint, for example, the connection to health.

More detail would enable us to know if there is a problem affecting only certain groups in the age structure and help identify the reasons. One way to address the problem and monitor change is to divide the population into equal age blocks and treat each separately using the concept of partial life expectancy.

For example, a partial life expectancy of 8 years means you are only expected to live eight of the next ten years. We extend this analysis to cover people aged 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 and compare trends at each age bracket since 1950. This timescale covers a period that saw very rapid increases in life expectancy globally and is sensitive to small changes from year to year.

From a technical standpoint, any statistical trend fitted to the data needs to be a non-decreasing function. We also need to reflect that there are natural limits to life expectancy, meaning that we do not project infinite life spans, in particular recognising that you cannot live longer than 10 years in the next 10-year age interval.

Mayhew and Smith (

2015) show that partial life expectancy is additive, meaning that the accumulated gain equates to the expectation of remaining life by aggregating across the decades. This property means we can examine trends within each decade of life to pinpoint in which age intervals future increases in life expectancy are more likely to occur.

The method used follows closely that set out in

Mayhew and Smith (

2015). By dividing lives into a set of ten-year blocks, we are not forcing the data to fit an arbitrary upper limit but are constrained so that it cannot exceed 10 years, the maximum possible. We are then able to chain-link expectations of life together to get an aggregate life expectancy projection built on the component parts at various stages of life.

Because of its convenient properties and the ease with which the parameters can be estimated, the most useful function as assessed by Mayhew and Smith is a form of the logistic function which can be written as follows:

where

is a polynomial equation of order

n which takes the value of one or two. That is:

or

in which

,

and

are parameters to be estimated,

t is calendar year, and

y is life expectancy in age interval

i. is a constant defined by the user taking all age intervals to be equal and in this case is set to 10 years, the maximum achievable within the age interval.

Transformed into this form parameters , and can be readily estimated using ordinary least squares regression. Parameter measures the speed at which saturation level is approached and , is a vertical axis scaling factor which varies with age bracket; is similar to and is a shape parameter which is useful in low mortality countries, such as those considered here and improves model accuracy.

2.2. Results

Although we were particularly focused on the UK, we evaluated the model on a range of other developed economies. We focused on trends in each of eight age groups starting at age 30–40 and ending at ages 100+ using life tables from the Human Mortality database (HMD)

2 each year from 1950.

We stopped in 2010 in order to investigate how effective the model was in predicting the effects on partial life expectancy of factors affecting the general economy and in the COVID period. We could then compare any consequent perturbations with the long-term trend predicted by the model and account for the reasons.

A downturn in life expectancy due to COVID was widely expected but we did not know by how much. Similarly, the period between 2010 and COVID was a time of austerity in public finances post the 2008 global final crash and corresponded in the UK’s departure from the European Union.

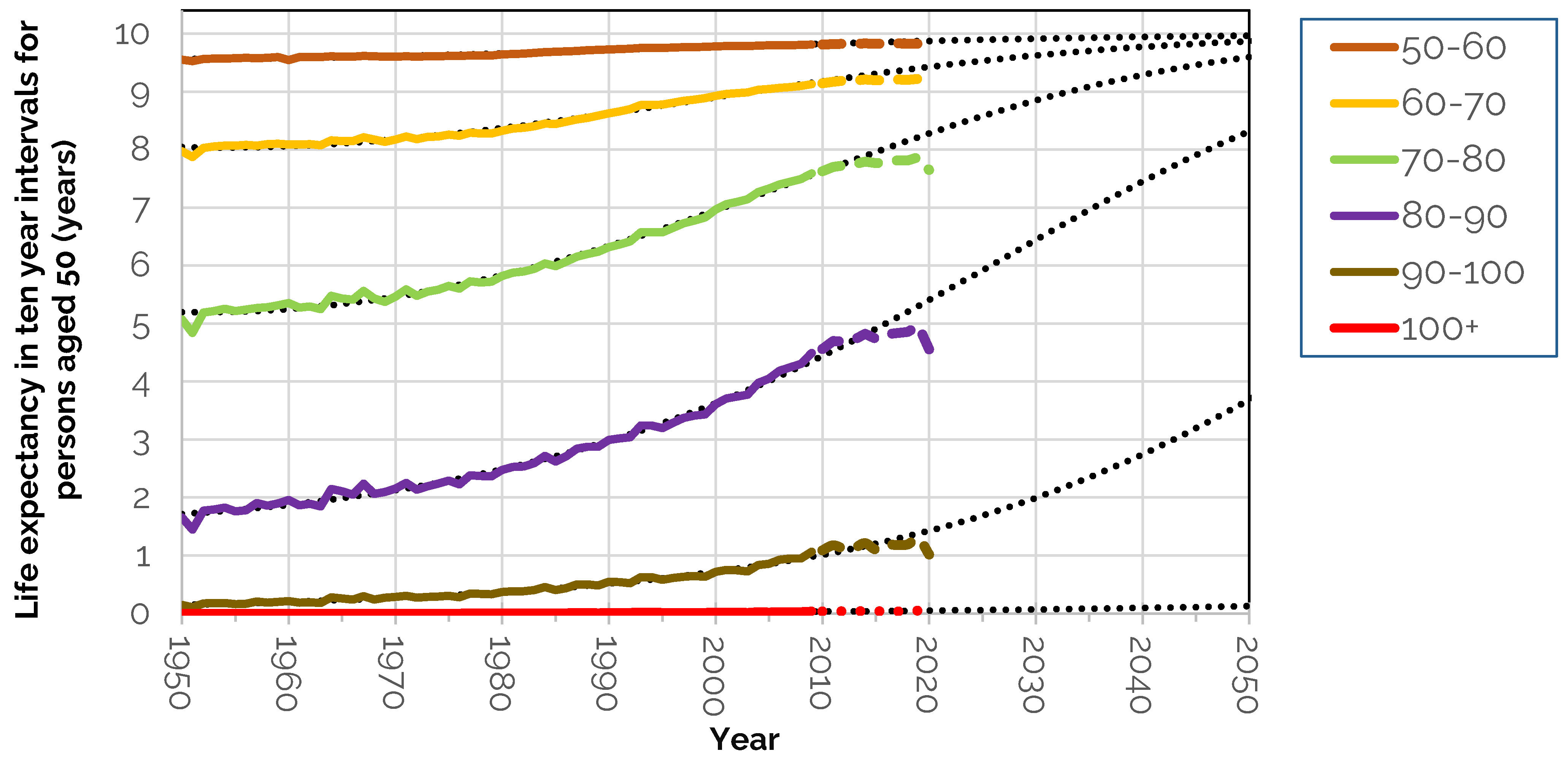

The results for the UK are shown in

Table 1 for each of the parameters,

,

and

and

which measures how well the model fits the data. This ranges in value from 0 to 1, a perfect fit. They strongly indicate that increases in life expectancy have occurred in a predictable wave-like fashion as people age—as opposed to a process in which each age interval has contributed equally.

This can be seen in

Figure 1 which shows predicted and observed values of partial life expectancy from age 50 to 60 upwards. It is not necessary to show in the same chart younger ages from 30 to 40 and 40–50 since partial life expectancy is remarkably close to its maximum value of 10 years throughout these stages of adult life.

The result is a shift in survival at higher ages improving their position relative to previous years and in relation to younger ages. If projected each survival curve would converge to its 10-year limit. Clearly whilst this has already happened at younger ages, it is still far off at the oldest ages—so, for example, in the 80 to 90 age group survival is still less than 5 years out of the next ten whilst life expectancy post-100 has barely changed.

If the trend continued in predicted fashion, then the survival curve would become more rectangular in shape, a process which is known as the compression of mortality (

Wilmoth and Horiuchi 1999;

Kannisto 2000). We do not address this question here (see for example,

Mayhew and Smith 2015), but our focus instead is on the recent past and near future, concentrating on short-term changes only.

Other significant points arising from the chart in

Figure 1 are that between 1950 and 2010, UK life expectancy at age 50 increased by 7.9 yrs. to 32.3 yrs.

Table 2 shows that the biggest improvements were at ages 70 and 80 where partial life expectancy increased by 2.6 years and 2.9 years. At age 60 it improved 1.2 years but at 50, 90 and 100 improvements were less than one year.

The next step was to compare the life expectancy data post 2010 with what would have happened if the long-established trend had continued. This is shown in

Figure 2. Here, the dotted black lines show the long-term trend in life expectancy of UK 50-year-olds by ten-year age segment. Thicker hatched lines show the deviation from trend in actual life expectancy from 2010.

A slowdown in improvement is seen from around 2010 onwards—long before COVID arrived—but there is also a marked COVID effect in 2020. Deviations from the long-term trend in life expectancy are shown by age group in

Table 3. Declines initially affected 60, 70 and 80-year-olds from 2013 based on row one; 80 to 90-year-olds were next in line.

By 2018 life expectancy among all those aged 50+ was not only one year lower than trend but lower in absolute terms. When COVID struck, 70–80 and 80–90-year-olds suffered most, resulting in a combined fall in life expectancy of 2.3 years over the period in all age groups (bottom right corner of

Table 3). Closer examination shows that life expectancy began noticeably to stall in 2013; declines initially affected 60, 70 and 80-year-olds; and then 90-year-olds.

2.3. UK Compared with Similar Countries

We compared the UK with similar advanced economies. During the period from 1950 to 2010 we saw that UK life expectancy at 50 increased by 7.9 years, Japan saw a rise of 13.5 years, while the USA recorded the lowest increase in comparator countries, adding 5.9 years. In this period the UK was consistently among the bottom-ranked countries—with the US being the lowest ranked.

Drilling down, we find the UK is one of only five major countries with stalled life expectancy since the start of the second decade of the new millennium. Out of 17 comparators, 12 increased life expectancy at age 50 between 2010 and 2020. Norway (+1.8 years) was most improved, followed by. Finland (+1.5 years) and Australia (+1.5 years). Least improved but still positive were France and Netherlands. Those in the ‘stalled’ category were Switzerland (−0.6 years), US (−0.2 years), Italy (−0.2 years), Spain (−0.1 years), and the UK (−0.1 years). The table at

Appendix A Table A1 provides the details.

Declines in life expectancy are a warning sign of shortened working lives—which could have dire implications on the UK labour market and the economy as we speculate in later sections. We do not know if the decline we observe is a temporary blip or a transition to a new norm. Even if it is a blip, it is likely to take several years to get back to trend.

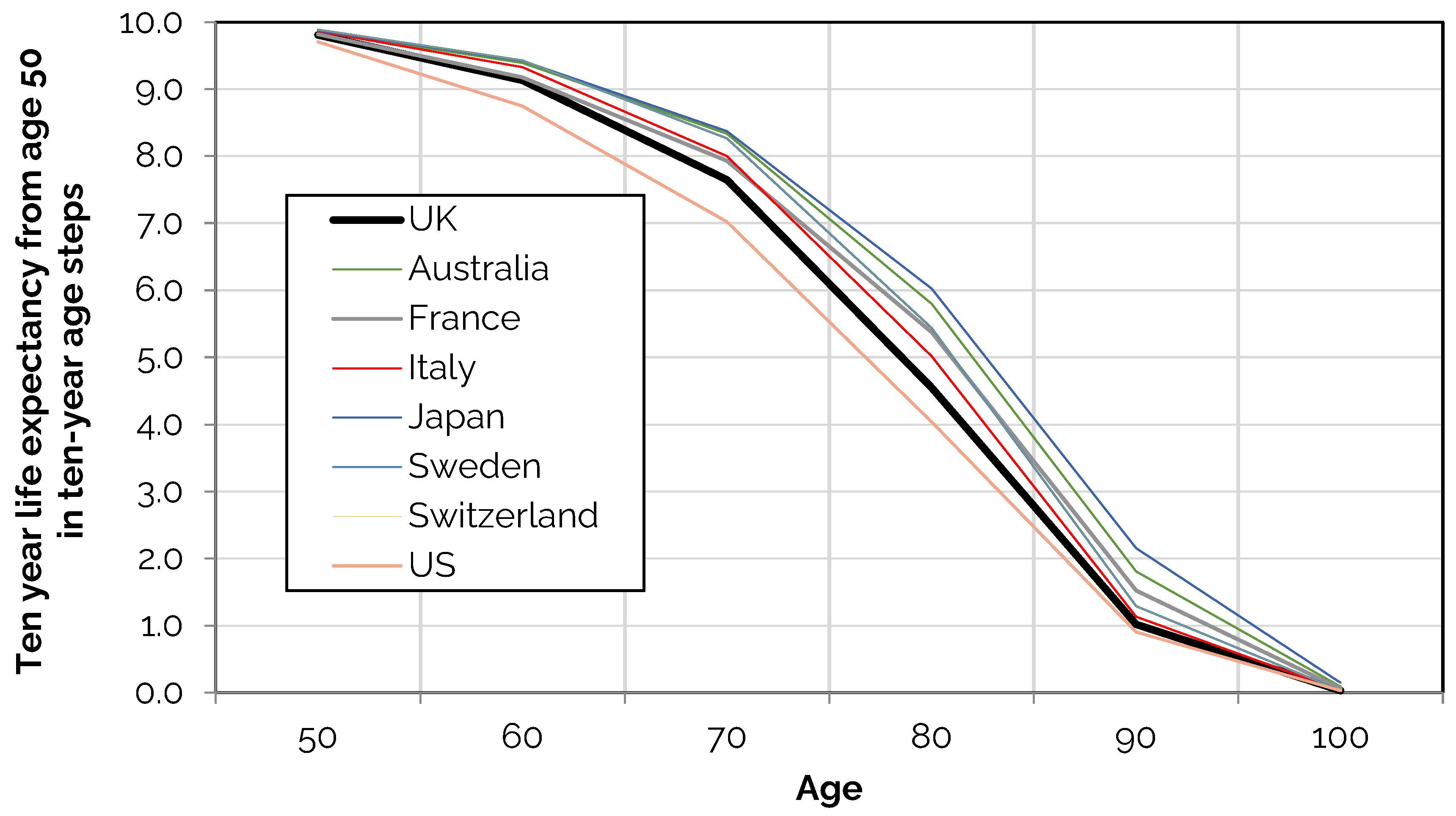

Table 4 and

Figure 3 show the extra years out of the next ten a person can expect to live by ten-year age interval in eight leading countries in 2020. The total at the foot of each column is life expectancy at age 50 and is lower in the UK than in every country except for the US. The same applies in each individual age category with countries including Australia, France, Italy, Japan, Sweden, and Switzerland all doing better.

The largest gap in partial life expectancy occurs is at ages 70 and 80, ranging from 0.8 to 1.5 years of the next ten years if the UK is compared with Japan. The most telling statistic is that a 50-year-old Japanese person can expect to live 3.8 more of their remaining years than someone from the UK. If we want people to live longer and more healthily—and to work longer—these differences need to be reduced.

3. Health Expectancy by Age and Deprivation

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) defines healthy life expectancy as the number of years an individual is expected to live in self-assessed good or very good health

3, and is, by definition, lower than life expectancy. Measures of both are available in different forms, enabling detailed comparisons of health and life expectancy by age and area type.

Whereas as life expectancy is based on death registers, estimates of health expectancy are based on data from the Annual Population Survey

4—which is an annual cross-sectional survey of around 320,000 households covering people aged 16 to 95. We use these estimates to compare health expectancy using the same partial approach as in

Section 2.

Changes in life expectancy are linked to health changes which can have a wide impact on the health and care economy in general. On the face of it, one might expect to find health and life expectancy to move in lockstep, but this paper shows the relationship is more complex and varies by age and area.

We use the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)

5 to divide the country into deprivation deciles—with decile one being the most deprived and decile ten the least deprived. The IMD is a widely used measure of relative deprivation in England in which small areas are ranked on different components of deprivation. These include employment, education, health and disability, and housing. Each decile is compiled from small areas with similar characteristics and so does not refer to a geographically bounded region or area.

The positive correlation between poor health and other index domains suggest that they are linked even if the direction of causality between each domain cannot be specified exactly. Nevertheless, such links indicate pathways that show being in good health underpins well-being—one example of this is the link between good health and employment.

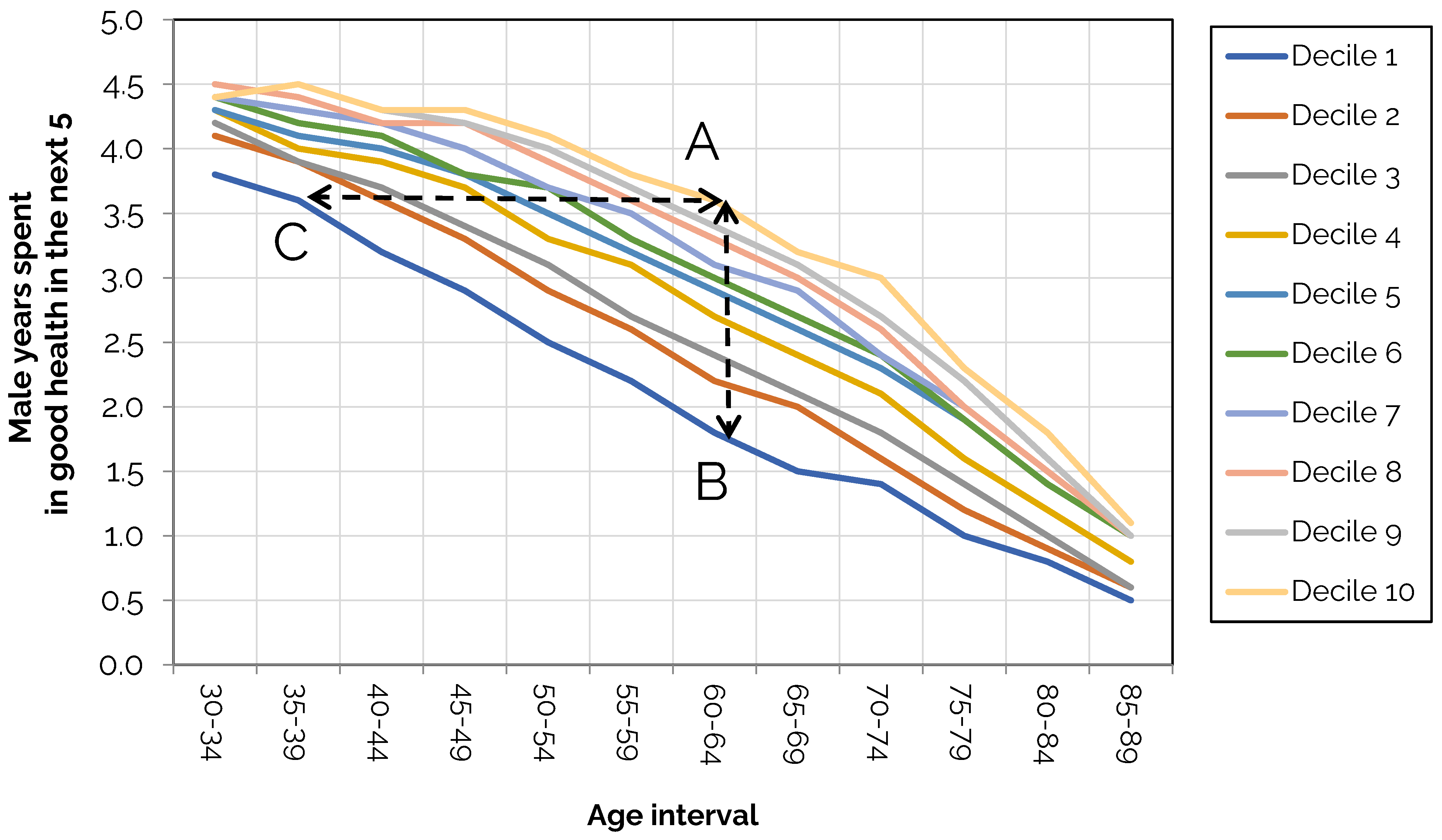

Using ONS data on health expectancy by deprivation decile, we calculated the number of years out of the next 5 years a male adult could expect to live in good health by age.

Figure 4 splits the data into 5-year age ranging from 30 to 34 to 85–89 with health expectancy on the vertical axis.

The results show wide dispersion in health with the least deprived deciles showing higher levels of health at every age. A vertical line drawn at any age is the difference in healthy years between the most and least deprived areas. The health gap is widest between ages 60 and 64. In decile 1, 1.8 years are spent in good health; in decile 10 it is 3.6 years (A to B) creating a gap of 1.8 years in this age bracket.

We also see that a male aged 60 to 64 in decile 10 has the same expectation of good health as a man aged 35 to 39 in decile 1 as denoted by the dotted line (A to C). As

Table 5 shows, either side of 60–64 the gaps are narrower, suggesting deprivation has a smaller effect at younger ages whilst a narrowing of the gap from ages 66–69 upward is a selection effect due to the earlier dying out of less healthy people. We also find similar variability occurring with women, but it is less extreme.

Interestingly the pattern of inequalities is comparable to data from 2011 to 2013, suggesting the pattern is locked in—at least for now. The persistence of these patterns underlines how difficult it is to achieve improvements in health at a macro scale– and, as we will argue, much of the challenge is down to lifestyle differences at least as much as healthcare funding.

3.1. Health Expectancy Compared with Life Expectancy

How does this compare with life expectancy by deprivation decile? Here we find life expectancy is also lower in deprived areas, but the dispersion compared with health expectancy is less. To see this key finding,

Figure 5 and

Table 6 show the extra years out of the next 5 a man can expect to live by age and deprivation decile which is a much more bunched pattern.

As

Table 6 shows, the gap in life expectancy is consistently less than the gap in health. For example, it falls to 3.2 years at age 70–74 compared with 4.1 years in the least deprived decile, a difference of 0.9 years (PQ). This compares with only 1.4 years in health expectancy in the same age bracket compared with 3 years in the least deprived decile, a gap of 1.6 years (

Table 5).

Taking it together, we can infer that life and health expectancy are in an asymmetric relationship with respect to deprivation. Whilst a lower health span leads to shorter lives on average, the gap between health span and life span varies across the life course. Most people aged 55–59 can expect to live all the next five years. For people in decile one health expectancy is only two years of the next five in the same age bracket.

In sum, the charts show that health span is more affected by deprivation than life expectancy and that the gaps between them are highest in middle age and least among young adults and older people. The question is not only why this happens but also what the social and economic ramifications are.

3.2. Geographical Variation in Health Expectancy

We have seen how inequalities in life expectancy are less than inequalities in health span, findings that apply to both men and women. Either spend more years in ill health per 5-year age interval over the life course as well as die sooner.

In this section, we show that this pattern translates at the geographical level as well as by deprivation decile.

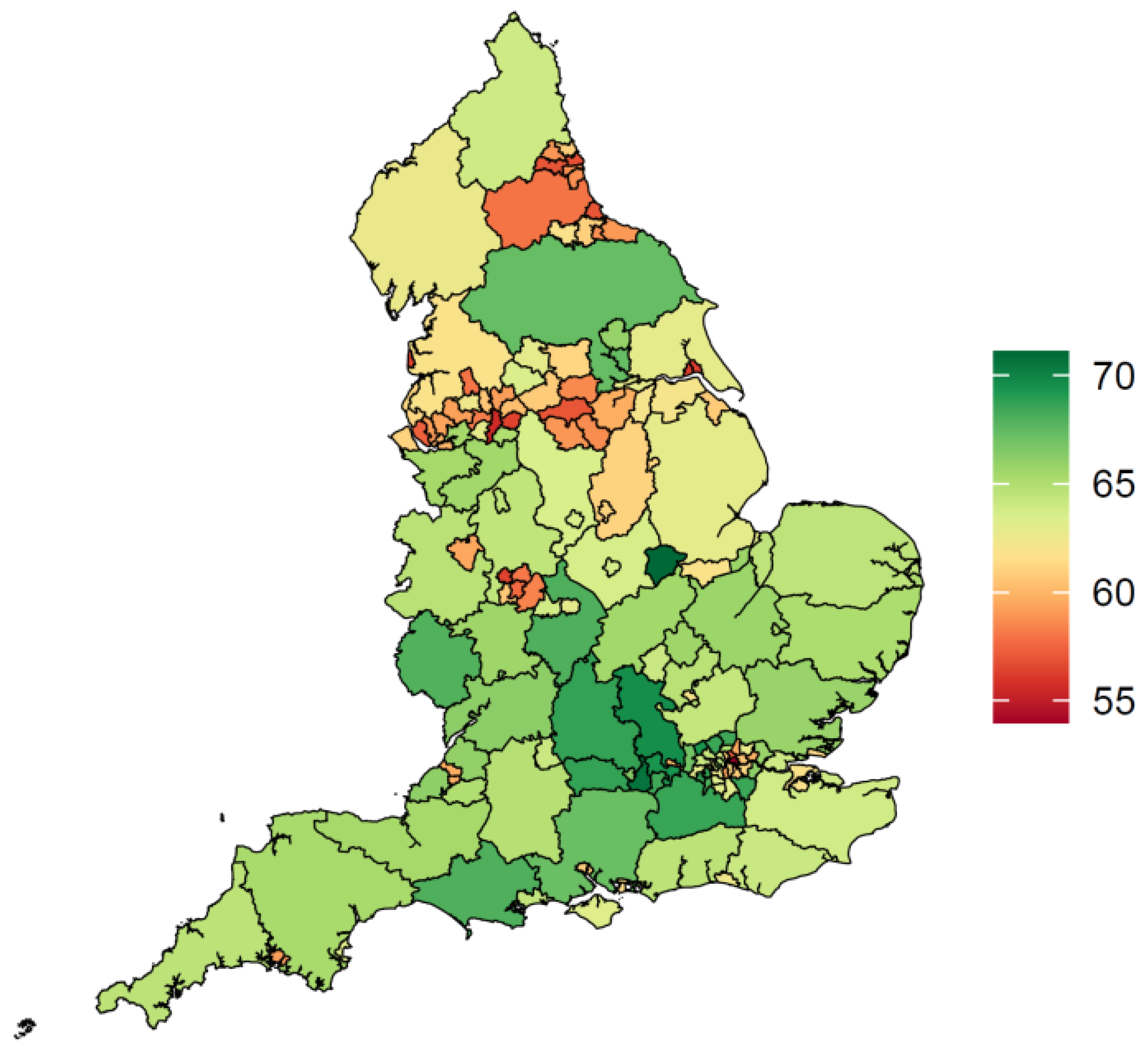

Figure 6, taken from

Mayhew et al. (

2024), highlights a characteristic spatial footprint of health expectancy, with northern urban areas of England doing significantly worse than the south, with some exceptions in more rural areas.

We find, similarly to our earlier decile analysis, that the range of variation in life expectancy is less than the variation in health, giving rise to much larger gaps in areas with poor health. This can be seen in

Figure 7 in which we plot life expectancy and health expectancy at birth on health expectancy.

The chart is based on 150 observations using data from 2016 to 2018, with each symbol representing a different upper-tier local authority

6. Actual values of life expectancy range from 74.5 to 83.9 years in the longest-lived area as compared with 53.3 to 71.9 years in health expectancy. A regression line of life expectancy on health expectancy shows that life expectancy and health are highly correlated, as one would expect (R

2 = 0.70).

We see, however, that the vertical gap between healthy life expectancy and life expectancy is 21 years in the least healthy district and among the healthiest 12 years, a 9-year difference. The district with the highest health expectancy is Rutland at 74.7 years, followed by Richmond-upon-Thames in London at 70.3 years, with Blackpool the lowest at 53.5 years.

Further analysis finds that a one-year decline in life span reduces health span by 2.37 years based on the regression analysis. As a result, people in areas with the lowest health expectancy consume more healthcare, are less likely to work and, when they do, are more likely to take time off work and earn less

7.

Causes of ill health are both direct and indirect but several are lifestyle related.

Mayhew et al. (

2024) show that deaths from smoking, a major cause of death, are higher in urban areas—most noticeably in a band linking Blackpool, Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, and Hull which is borne out in

Figure 6.

Tellingly, smoking not only shortens lives but also reduces both health expectancy and working lives with a gap of around six years between non-smokers and never smokers at age 20. There are other risk factors, such as diet, lack of physical exercise, and alcohol consumption, which effectively compound risk when they are co-present (

Birch et al. 2018). Obesity, which affects 30% of the adult population, is a good example.

It is easy to find examples of how poor health affects levels of economic inactivity. For example, Blackpool, with a life expectancy of 54 years, has an inactivity rate of 31.1% whilst Surrey in southern England has a life expectancy of 68.6 years and an inactivity rate of 17%. Overall, we find that each one-year increase in health expectancy is estimated to increase by 1.1% so a 5-year improvement would see a 5.5% increase.

In most local authority areas, we also see that health expectancy is below the previous State Pension age of 65

8. In 108 of the 150 upper-tier authorities, health expectancies for men are below state pension age, which equates to roughly 1.9 m men of working age. For women, the situation is slightly better with 99 districts below state pension age and 51 above.

How to close this gap is of strategic importance—especially as the country ages and more people succumb to age-related lifestyle illnesses (

Lynch et al. 2024). As State Pension age increases, many will have to wait longer to receive it and may struggle to live if they are unable to work because of poor health. These findings also create a dilemma for setting the state pension age, which the government reviews periodically (

DWP 2023).

4. Discussion of Economic Repercussions of Stalled Life Expectancy and Health

We have seen that life expectancy in the UK has stalled after decades of improvement. This paper has shown that the problem predates the onset of the pandemic by at least six years. Partial life expectancy analysis revealed clear patterns linking poor health and life expectancy at various ages due to deprivation. However, the two measures are not in lockstep, and the damage done to the economy through poor health is greater than a fall in life expectancy.

The last 15 years or so have brought to the fore underlying problems which have seen economic stagnation and lower than needed funding for big tax-funded programmes like healthcare. It is also obvious that life expectancy is at a moment of crisis as the UK struggles to regain lost years since the pandemic and before, as our analysis suggests.

Critics blame the previous government for the crisis, pointing to inadequate COVID preparedness and squeezed NHS and public health funding during austerity. There is also contested evidence that local government funding reductions and increased numbers on welfare benefits are associated with greater falls in life expectancy in deprived areas (

Alexiou et al. 2021;

Seaman et al. 2023).

Without major changes, current trends suggest that existing inequalities are likely to persist and even increase (

Raymond et al. 2024), given the limited progress to date. With current policies alongside an increasingly ageing population, the health of the nation will worsen and be ever more costly in public expenditure terms. However, many of the problems are traceable to poor health behaviours, and so modifiable with the appropriate policies such as smoking cessation or a healthy diet.

There are three interconnected policy domains to consider from a public finances perspective: first, the high levels of economic inactivity linked to poor health and economic stagnation, second, the spiralling cost of health treatment and lengthy waiting times due to health inequalities and squeezed funding, and third, increases in related welfare spending on disability and sickness benefits that are the consequence. This negatively affects other areas of policy, albeit indirectly, such as the upward financial pressure on the state pension, which is a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) tax-funded arrangement.

Health is a common thread, or more specifically, poor health, which, if it could be improved, would both reduce the tax burden and increase productivity (

L. Mayhew 2023). To give one example, the cost of inactivity is reflected in the bill for working-age health-related welfare benefits; these have surged from £36bn before the pandemic to £48bn in the last financial year and are expected to reach £63bn in the next four years, according to the Office for Budgetary Responsibility

9.

Economic inactivity is also linked to higher immigration, which is running at around 0.5m a year. The demand for labour is broadly fixed in the short term, and what we have seen is much higher immigration to fill lower-paid jobs, especially. Currently, there are 9.2 m economically inactive people in the UK that could potentially fill these jobs; of these, 2.8 m are long-term sick compared with 2.1 m in 2019. Not only does this illustrate the scale of the problem, but it also hides consequential impacts on other policy domains like housing because of immigration-fuelled population growth.

In an ideal world, people would be healthier if they led healthier lives, but it could take generations for this to seep through to society, as the slow decline in smoking habits demonstrates.

Mayhew and Cairns (

2025) show how prevention could be a lifeline for the NHS by reducing the ever-increasing cost pressures on health services by adopting better metrics linking the financial benefits of better health to taxes and work.

As an illustration, an ONS survey

10 found that 20% of the population in England were waiting for treatment whilst the number on the waiting list increased threefold from 2.5 m in 2010 to 7.5 m today. A significant part of this rise is attributable to those waiting for mental health treatments. The sharp rise in mental health problems could indicate that inactivity is itself a risk factor, as suggested by some (see, for example, the Health Foundation

11). The fact that this group includes younger adults is also worrying because the root cause is not population ageing.

We have also seen that the UK state pension is not immune to financial pressures. As the number of older people increases, there are calls to raise pension age to save money (e.g., see

LCP 2023). Equivalently, a rise in economic activity rates through a one-year increase in health span would increase the tax base and ease this.

L. D. Mayhew (

2021) points out that if economic activity rates were to increase from 78% currently to 84% the extra tax revenues generated would allow a postponement to the already announced increases in state pension age.

Given that poor health affects all policy areas adversely, what is needed to improve overall health? We have seen that lifestyle factors include the lack of physical exercise, smoking, excessive drinking, drug abuse, mental illness, and obesity (

Marmot et al. 2010;

Fone et al. 2013;

Ford et al. 2021). Moreover, risk factors are often interrelated, meaning that reducing one risk factor may lead to a decrease in the prevalence of others (e.g., see

Fat et al. 2017;

Birch et al. 2018).

If we take cancer, which is the second most common cause of death, smoking is only one of several risk factors. US research (

Islami et al. 2017) found that 47.9% of deaths from cancer were attributable to avoidable risk factors, including cigarettes (33.1%), excess body weight (5.7%), alcohol (4.3%), and other factors such as low physical exercise and diet (4.8%). Smoking, often linked with heavy drinking, also contributes to deaths from heart disease and other causes (

Murphy and Di Cesare 2012).

Smoking alone kills about 78,000 people in the UK from smoking-related diseases. This comes at an immense cost to the economy.

Reed (

2024) shows that the net cost to public finances is £13.5 bn as measured in higher health and social care costs, disability benefit payments, and lower tax revenues, after subtracting the effect of income from tobacco duties. Reed further estimates productivity loss at £54 bn, which is so much larger than the effect on public finances.

In terms of the difference a smoking ban would make to health, it is calculated by

Mayhew et al. (

2024) that areas in the poorest health would eventually gain up to 4.6 years in health life expectancy compared with 0.2 years in the healthiest with the lowest smoking prevalence. Life expectancy would rise as a result, aligning the UK with other countries but still falling short of closing the health gap entirely. Hence, none of this is sufficient to level up health, but it is a start.

It is worth re-emphasising that the health benefits of prevention can take decades to materialise and require large behavioural changes. Benefits accrue only slowly in the lifetime of a typical parliament, and so actions that would improve health tend to be shelved because they might affect business and be unpopular among voters. The legislation going through Parliament to ban the sale of tobacco to anyone born after 2008 is a big step forward, but it will make little noticeable difference for a couple of decades.

5. Conclusions

This study employed innovative decomposition methods to analyse health and life expectancy at different ages. It found that UK life expectancy stalled after 2010 and that the subsequent drop due to COVID is the second highest among seventeen advanced economies after the US. Out of seventeen, life expectancy stalled in five countries but increased in eleven, suggesting that these countries were better prepared for the pandemic than the UK.

The asymmetrical relationship found between health and life span at the sub-national level resulted in deprived areas spending more years in poor health, as well as a greater proportion of their lives (

Bennett et al. 2018). The scale of inequality has had a major impact on different areas of public expenditure—whether in healthcare, welfare benefits, economic activity, or, indirectly, pensions. We conclude that poor health is a key factor why the UK economy has struggled since 2010, following the 2008 financial crisis and now COVID, constraining economic growth and driving up public sector costs.

There is a need to understand both the economics of ill health and the case for a much-strengthened role for prevention, but there is no magic wand. A comprehensive approach is needed for assessing the full cost of ill-health over the life course, linking health and finance together. Elsewhere,

L. Mayhew (

2023) has shown that a five-year improvement in health expectancy would increase life expectancy by two years and extend working lives by almost one year, whilst reducing the tax burden by 2.4%.

The unresolved policy issue is how to do this in an evidence-based way, and the timescale and policies involved. Expressing the financial benefits of good health fills a gap and opens the way to create new, financially based health metrics and more innovative policies (

Mayhew and Cairns 2025). The need for change is urgent, given the UK’s rapidly ageing population and stagnating economy.