1. Introduction

The world is becoming increasingly conscious that firms conduct business activities that have an impact on society and that these consequences extend far beyond the profits reflected in an accounting income statement. Corporations conduct business activities that have an impact on the environment, people’s lives, and on notions of ethics and transparency. As a result, corporations have a responsibility to both their shareholders and society to explain their actions and to ensure they are reporting their actions accurately. These corporations are increasingly being held accountable for the ecological, societal, and ethical consequences of their operations. Investors are becoming more mindful of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concerns when making investment decisions. There are four major reasons for doing so—(a) integrating portfolios with investors’ values and standards, (b) generating social impact by pressuring corporations to act ethically, (c) limiting exposure to different risks (climate, litigation, or legal risk), and (d) favoring sustainability by rewarding ESG adopters.

ESG issues are receiving more attention from corporate boards all over the world. Environmental criteria assess how a corporation protects the environment, such as its corporate policy addressing climate change. Social criteria focus on how the company maintains associations with its employees, suppliers, consumers, and the communities in which it operates. Governance is concerned with the leadership of a corporation, executive remuneration, independent audits, control systems, and the interests of shareholders. ESG disclosure refers to the qualitative and quantitative reporting of data by a company on its operations based on ESG standards. Though ESG disclosure is widely acknowledged as an important indicator of company sustainability, standardization of these disclosures has not yet occurred. Diverse rating agencies publish ESG performance indices that are based on diverse approaches (

Huber et al. 2017), which may impede investors’ decision-making (

Matos et al. 2020), and organizations are attempting to meet only the bare minimum. Currently, investors lack access to standardized data that may be used to detect ESG risks and opportunities.

This study focuses on companies in the Indian capital market, as India is among the fastest-growing emerging markets and started its ESG journey some time ago. As a result, India is most suited for a study on the effect of disclosure on security returns. As per

PWC (

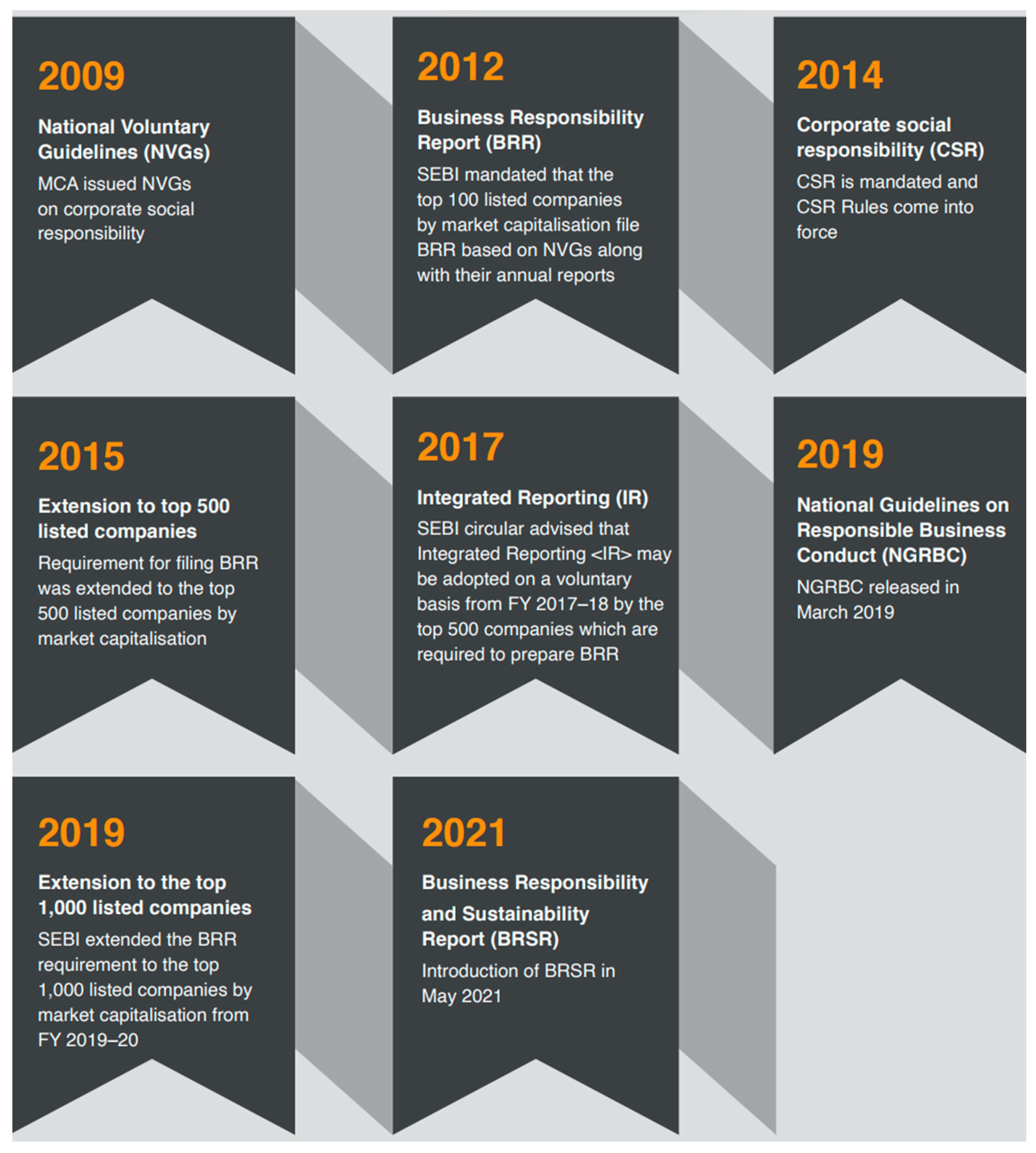

2021), India started its sustainability journey in 2009 with National Voluntary Guidelines (NVGs) and moved ahead in 2012 and 2014 with Business Responsibility Report (BRR) and Corporate Social Responsibility as part of the new Companies Act 2013, respectively. Since then, the reporting standards have been becoming more stringent and applicable to an increasing number of firms. The evolution of ESG reporting in India is depicted in

Figure 1. Most studies have analyzed the impact of ESG performance and ESG disclosure in the developed markets in Europe and the U.S. The Indian capital markets are different and much less studied by researchers on ESG implementation and its implications. Additionally, as India is in the transition stage, it will present the findings suitable for the economies planning to mandate ESG reporting.

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) had mandated the biggest 1000 listed on Indian stock exchanges to report their ESG data following the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting (BRSR) standards (

SEBI 2023). Though the companies have to submit an ESG report, all ESG-related disclosures are voluntary, and the company may choose to disclose what it prefers and may conceal what it may not like.

Zhang (

2022), in their study, evaluate the various factors a firm may choose to disclose or not to disclose. The main aim of the current study is to evaluate whether ESG-related disclosures aid a company in its financial performance. The literature is ambiguous on the topic of whether the financial performances of firms disclosing to the fullest extent earn any premium over the ones that do not. This study is an attempt to understand the relationship between the disclosure of ESG data by companies and their financial performance relative to their peers. Do investors give preference to ESG disclosure while choosing investments? We hypothesize that the relationship between ESG disclosure and stock returns should be negative and informed through a literature survey. However, the investor voices and government regulations also make it sound that ESG performance and ESG reporting are desirable. Many funding houses and investment bankers use ESG strategies that outrightly oust the firms not disclosing ESG information. This, in turn, should reduce the demand and, thus, prices for opaque stocks, giving the benefit to ESG-disclosing companies. Another side of ESG disclosures is highlighted by

Kim and Lyon (

2015) whereby firms often use disclosures to greenwash themselves. Greenwash entails a company publishing confusing or misleading information to show itself as an ESG-compliant company, even when it is not.

Kim and Lyon (

2015) also state that companies doing well on the ESG front may choose not to disclose their activities, as some investors may consider it a waste of resources and a charge against their earnings. This phenomenon in the literature is known as brownwashing.

This study contributes to the literature in the following manner. It provides an approach to test the relationship between ESG disclosure and firm performance. Secondly, it provides fund managers and wealth advisors with a method to incorporate ESG into fund management practice and provides a practical way for corporates to plan their disclosure for maximizing security returns. This study finds a negative relationship between ESG disclosure and firm performance; it serves as an advisory to organizations that they should structure their disclosure according to their requirements and not simply disclose because it is required and everyone else is doing it.

This study is organized as follows. The next section presents the introduction and evolution of the asset-pricing models. The subsequent section gives a briefing on the Indian equity market and its organization.

Section 4 discusses important studies on the detection of factor premiums and the use of ESG as a factor in asset-pricing models.

Section 5 discusses the data and methodology utilized in this study.

Section 6 discusses the descriptive and inferential statistics on factor premiums and their explanatory power in the models. The last section summarizes and concludes the study.

2. Asset-Pricing Models

There has been a significant advancement in the field of asset-pricing literature since the publications of the CAPM single-factor model by

Sharpe (

1964),

Lintner (

1965), and

Mossin (

1966). Contradicting the CAPM, the operation of capital markets is more sophisticated, and it is practically impossible to capture all the fluctuations using a single-factor model.

Black (

1972),

Fama and MacBeth (

1973),

Ross (

1976),

Banz (

1981),

Basu (

1983),

Shanken (

1985),

Bhandari (

1988), and

Khandelwal and Chotia (

2022), among others, provided critiques and challenges to the CAPM. Along with beta, using the size of the company as another important variable that helps explain expected portfolio returns was argued by

Fama and French (

1988,

1992,

1993) along with

Gibbons et al. (

1989) and

Lo and MacKinlay (

1990). Studies conducted by

Basu (

1983) and

Reinganum (

1981), among others, found that the P/E ratio is an important explanatory measure for security returns.

Bhandari (

1988) and

Narayanaswamy and Phillips (

1987), among others, found leverage as another important factor that explained the variations in portfolio expected return.

Fama and French (

1993) presented a three-factor model (FFTF) using size and value factors that were empirically more stable than the two-factor models used in earlier studies.

Fama and French (

1993) was also criticized and challenged by several studies (

Haugen and Baker 1996;

Fairfield et al. 2003;

Titman et al. 2004;

Novy-Marx 2013;

Hou et al. 2015; etc.) on the grounds of other unidentified capital market anomalies.

Carhart (

1997), in his study, added a momentum factor to the existing FFTF, increasing the overall performance of the model. Recently,

Fama and French (

2015) introduced a five-factor model (FFFF) with additional investments and profitability factors, arguing that firms that actively invest their earning earnings command a premium, and the profitable firms earn more stock returns, as they have more earnings to distribute/reinvest. The FFFF model faced backlash due to the inadequacy of the model to reflect the risk–return fluctuations for micro stock portfolios. In a similar vein, the majority of the research (e.g.,

Hou et al. 2015;

Clarke et al. 2016;

Chiah et al. 2016) carried out across the world discovered that Fama and French’s five-factor model is unable to capture all of the risk–return variations and, thus, cannot be called a global model. Models with additional factors are continually being researched, checking the significance of more factors.

Rosett (

2001),

Qin (

2002), and

Maiti and Balakrishnan (

2018) explored the role of human capital in explaining stock returns and found promising results.

Henriksson et al. (

2019),

Hübel and Scholz (

2020),

Lajili et al. (

2020),

Price (

2022), and

Maiti (

2021) are a few of the researchers utilizing ESG as a factor in explaining the financial performance of companies.

Tripathi et al. (

2022) explored the economic-value-added concept and discussed its role in explaining the returns of a company. The search for additional factors is ongoing until a perfect model is reached. This study is an attempt to complete the asset-pricing puzzle using ESG disclosure premium as an additional factor for explaining security returns.

4. Literature Review

One thousand chief executive officers (CEOs) from all over the world were surveyed by the United Nations Global Compact in 2013. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG)-related issues were crucial to the performance of more than 93% of the responding CEOs’ businesses (

UN 2019). Pressures from diverse sectors are crucial to the growth of sustainable finance. Increasingly, stakeholders are concerned about how profitability is attained. Customers across all industries are becoming increasingly interested in the business practices of organizations and are keen to support ethical enterprises. Companies are increasingly compelled by new rules to comply with minimal ESG standards. The methodology used by credit rating firms now values ESG scores and disclosure. Several rating agencies recently pledged their commitment to include ESG elements in their credit rating process by signing the Principles of Responsible Investing (PRI) (

Ferguson et al. 2019).

The European Commission has committed itself to addressing sustainability challenges in the financial industry to create a common foundation for carbon disclosure and ESG procedures. The commission has established several expert groups, with a focus on sustainable financing (

Perissi and Jones 2022).

Al Kurdi et al. (

2023) investigated the factors that impact the ESG performance of the company in the European context and found that as the ESG-compliant firms do not experience problems (such as accidents, lawsuits, or government intrusion into management procedures) brought on by a lack of ESG practices in their everyday operations, businesses frequently regard ESG-related risks of low occurrences. Yet, businesses must control them to prevent unfavorable long-term effects (

Henisz and McGlinch 2019). According to Moody’s, 33% of private-sector issuers view ESG risk as a significant credit factor (

Venkataraman and Williams 2020). International engagement on ESG issues is encouraged by global initiatives, such as the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals. Similarly, the financial sector is experiencing comparable pressures.

BaFin (

2020) affirmed that sustainability-related risks are a vital component of risk management. Consequently, the risk profile of a company is unquestionably influenced by its management of ESG concerns, which impacts the behavior of its stock price. The upsurge of ESG disclosures can be explained by three main ideas: the legitimacy theory, which is based on organizational legitimacy (

Dowling and Pfeffer 1975); the agency theory, which is based on conflict of interests (

Jensen and Meckling 1976;

Khatib et al. 2022); and the signaling theory, which is based on the knowledge gaps between an organization and its stakeholders (

Spence 1973). In order to create long-term value, a firm’s commitment to ESG practices is shown to its different stakeholders through ESG disclosure. The battle for new talent is another significant driver of sustainability. Eventually, the younger generation entering the workforce will be more concerned with their companies’ stance on ESG issues. As investors realize the usefulness of ESG data to comprehend business purpose, strategy, risk management capacity, and management quality, ‘ESG analysts’ are infiltrating Wall Street (

Kell 2018). The consequences of not adhering to ESG requirements might be catastrophic when there are numerous stakeholders concerned with sustainability.

As the business’s stakeholders learn more about its ESG efforts, the business’s reputation grows, and its relationship with society becomes stronger (

Velte and Stawinoga 2020). When a company reports how many ESG projects it has completed, it shows that it cares about society, which makes it more legitimate in the eyes of the public (

Bamahros et al. 2022). The firm is rewarded with a difference in its share price, which shows that ESG disclosure has a long-term positive effect on the share price. This long-term relationship between the principal (the shareholders) and the agent (the top management) tends to eliminate the knowledge gap between industry and society (

Kim et al. 2014;

Sinha Ray and Goel 2022).

Branch et al. (

2019) highlighted three key strategies to effective ESG-based portfolio construction. The first strategy relies on a binary yes or no for inclusion of ESG-compliant securities and exclusion for those that are non-compliant, respectively. The second strategy relies on assigning differential weights on the basis of ESG scores. The third tactic, which combines exclusion with scoring, requires extremely intricate implementations.

Khan (

2022), in his review, presented three research streams arising from ESG disclosure—(i) ESG performance as a result of firm characteristics, (ii) ESG performance through corporate governance theories, and (iii) financial corporality of ESG disclosure.

Khan (

2022), along with

Kaiser and Welters (

2019) and

Lin and Dong (

2018), affirm that though ESG performance brings financial performance, firms with high ESG disclosure were observed to generate less returns compared with their counterparts with low ESG disclosure scores. This is contradictory, as without disclosure, a firm cannot have an ESG score and, thus, no access to ESG premiums.

Ioannou et al. (

2016) reported that companies report ESG (or CSR) in different ways. Most research on ESG reporting has been carried out using ratings and checklists from annual reports or company websites. (

Aerts et al. 2008;

Cho et al. 2010;

Al Amosh and Khatib 2023). Under the voluntary disclosure theory, a company’s ESG engagement can be used to predict its ESG reporting practices. Companies with a good ESG performance would choose to report much about their ESG activities, while companies with a bad ESG performance would choose to report as little as possible. (

Verrecchia 1983;

Dye 1985).

Cahan et al. (

2015) reported that good ESG performance leads to good WOM, which helps the company receive a higher valuation (or lower cost of capital) because of the good press. Some companies use ESG disclosure to “greenwash” themselves, even if their ESG performance is not as good as they say it is (

Cho et al. 2015). ESG reporting can also make a company look like it cares more about ESG than it does. Sometimes, managers might not want to talk about their ESG work because their investors might see it as a cost that lowers their returns. Because of this, a company that does well in ESG may lie about what it does in ESG (

Kim and Lyon 2015). The results of empirical research on the relationship between ESG performance and financial performance have been mixed. Some studies have found no link between ESG success and the way a company talks about its business (

Freedman and Wasley 1990). Others do not see a link between environmental success and disclosure. It is not clear how ESG disclosure affects value in the real world (

Gillan et al. 2011). Some studies (

De Villiers and Van Staden 2011;

Bruno et al. 2022) find a negative link, while others (

Dhaliwal et al. 2011;

Lyon and Maxwell 2011;

Gao et al. 2023;

Climent et al. 2021) find a positive link.

Walkshäusl (

2018) found incomplete data as a significant problem in ESG research. Across 22 established equities markets, he examined the impact of ESG traits on return. Over the 2002–2016 study period, the average proportion of companies with ESG ratings varied from 7% in Singapore to 35% in Ireland. In the United States, the nation with the highest average number of enterprises at 3604, 21% of firms, on average, have ESG ratings. The literature on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues is extensive but far from conclusive. An empirical test of the disclosure–returns relationship is performed using an asset pricing approach in the following section.

6. Results and Discussion

Using portfolio construction breakpoints from

Fama and French (

1993,

2015) and

Henriksson et al. (

2019), we formed two portfolios on size, three portfolios on value, and three portfolios on ESG disclosure.

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of portfolio returns sorted on size (small and big), value (high, medium, and low), and ESG disclosure (transparent, neutral, and opaque). The excess mean returns for the small portfolio was comparatively higher than the big portfolio, thus affirming the presence of a size premium (0.07%). Similarly, on observing the portfolio returns on value portfolios, the portfolio with low value (lower book-to-market ratio) was observed to have higher excess mean returns in comparison with high value (higher book-to-market ratio) portfolio, affirming the presence of a value premium (0.95%) in the Indian capital market. The excess mean returns on portfolios sorted on ESG disclosure scores presented a contrasting view. The portfolio comprising transparent stocks (high ESG disclosure scores) generated less excess returns in comparison with opaque stocks (low ESG disclosure scores), signifying a negative disclosure premium (−0.54%). The difference on the portfolio returns was not only based on average returns, but the risk component also varies significantly. The standard deviations (measures of risk) on the portfolios based on size were indifferent on the riskiness. On the other hand, the portfolios formed on value and disclosure had varied riskiness due to constituent securities. The portfolios with high B/M ratios had higher standard deviation in comparison with the securities with lower B/M ratios. Similarly, transparent stocks had comparatively less risks than the opaque stocks. The presence of factor premiums was further evaluated using double-sorting and triple-sorting of portfolios on the basis of interactions among size, value, and disclosure factor.

Table 2a–c summarize the descriptive statistics of portfolio returns sorted on interactions among size and value, size, and disclosure and between value and disclosure factors. It can be observed from

Table 2a that the value effect was dominant over the size effect. Size effect was observed; however, value premiums were more dominant. Another observation is the high standard deviation in the low portfolio compared with the high portfolios. Looking at the interactions between size and disclosure in

Table 2b, the disclosure effect was significantly observed, and the size effect faded except in the case of opaque portfolios. The standard deviation for transparent portfolios was less than that of opaque portfolios, suggesting investment in transparent stocks as less risky. The findings for interactions between value and disclosure factors were similar. Both value premium and disclosure premiums were dominant, with opaque stocks being riskier in comparison with transparent stocks.

Table 3 summarizes the descriptive statistics of portfolio returns sorted on interactions among size, value, and ESG disclosure. The portfolio formed at the intersection of small in size, low in value, and opaque in disclosure characteristics was observed to generate the highest average returns. In contrast, the portfolio formed at the intersection of big in size, high in value, and transparent in disclosure characteristics was observed to generate the lowest returns with high risk. It is worth noting that the companies chosen for analysis were the surviving constituents of the S&P BSE 500 index, and the companies who dropped below the market cap (excessive downward movements) were not part of the analysis, thus, the positive mean returns for all companies.

Table 4 summarizes the descriptive statistics of factor premiums—ERM, SMB, HML, and TMO. The factors ERM and SMB rewarded a positive premium to the companies, which is well-established in theory. The factors HML and TMO had negative mean returns, implying that (i) firms with high B/M ratios generate less returns than companies with low B/M ratios and (ii) firms with high disclosure exercise less returns compared with firms with low disclosure. The findings on ERM, SMB, and TMO were consistent with the expectations; however, the negative mean returns of HML factor contradicted the findings of established theories.

Table 5 consists of the pair-wise correlations between the independent variables. The range of correlations varies from −0.1744 to 0.0646, signifying no correlation. This suggests that there was no problem of multicollinearity in the dataset. Additionally, a variance inflation factor (VIF) test also confirmed that the variables were free from influence of each other.

The respective portfolio returns were then regressed using time-series regression, consisting of 8 single-sorted portfolios on size, value, and disclosure factors, with 5 independent variables consisting of 96 time-series datapoints each. The independent variables used in the regression were ERM (

Sharpe 1964), SMB and HML (

Fama and French 1992,

1993), TMO (

Henriksson et al. 2019;

Climent et al. 2021), and a binary variable for estimating the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on stock returns. The regression results are reported in

Table 6. The coefficients of all factor premiums and intercept term are reported in the first line along with the adjusted R-squared statistic. The second line consists of the associated t-statistic values in parentheses. The coefficients are also marked with an asterisk (*) to denote levels of significance of the coefficient of factor premiums. Regression results for all single-sorted portfolios returned an insignificance of ERM factor, which captured the excessive returns from the market portfolio. The ERM factor was significant in all asset-pricing models since its first use. The explanatory power of ERM was reduced as a result of inclusion size, value, and disclosure premium. Referring to the study of

Khandelwal and Chotia (

2022), the ERM factor is significant in a bivariate relationship with portfolio returns. Another important observation from the regression results is the insignificance of the TMO factor for transparent portfolio. The results by regressing double-sorted portfolios are arranged in

Table 7.

The findings from the single-sorting approach are evident in double-sorted portfolios as well. The ERM factor was insignificant in explaining the portfolio returns. Similarly, for portfolios having any proportion of transparent stocks, the TMO factor became insignificant in explaining portfolio returns. The SMB factor was also insignificant in one instance of the big–high portfolio. Another interesting observation is the adjusted R-squared statistic of portfolios sorted on value. The adjusted R-squared statistic denotes the variance percentage explained by the independent variables in the dependent variable. The statistic had high values for portfolio consisting of stocks with high B/M ratio compared with its counterpart. This effect can be seen in interactions with size and disclosure factors as well.

Table 8 summarizes the regression results on triple-sorted portfolio returns. The observations from previous regression results are evident with additional explorations. The ERM variable was insignificant across all portfolios since the inclusion of TMO factor. The TMO factor was significant in explaining portfolio returns in all portfolios except those portfolios with transparent stocks. Both these findings were consistent in all three sorting approaches. New signals that were observed only in triple-sorting include insignificance of the SMB factor for the big–low–transparent portfolio and big–low–opaque portfolios. Similar insignificance was also observed in the big–high portfolio group, and the same was observed in the double-sorting portfolio of size and value. The binary variable ‘Dummy_Cov’ was also seen to be insignificant at 95% confidence level in a few models (SHO, SMN, SMO, BHN, BLN, and BLO), which may be due to the presence of the COVID-19 pandemic effect on other factors’ premiums. A decomposition of variance can be performed to understand the impact of each factor in explaining portfolio returns on different portfolios. The negative value premiums post-2015 were also observed by

Fama and French (

2021).

Fama and French (

2017) found large average value premiums in the Asia–Pacific region during 1990–2015. However, a later study (

Fama and French 2021) found that the returns on value portfolio during the study of the second half of the 1962–2019 period were significantly lower. This study used the data from 2014–2021 (SP1, henceforth) and found negative returns on the value portfolio in Indian capital market.

As part of robustness tests, this study further tested the performance of the TMO variable against the GMB factor, as it is established as a worthy factor in the asset-pricing puzzle (

Henriksson et al. 2019;

Pyles 2020;

Maiti 2021). The portfolio returns were tested for the impact of factor returns for the period from 2017 to 2021 (SP2, henceforth). The regression resulting from triple-sorted portfolios created from GMB and TMO are presented in

Table 9 and

Table 10, respectively. The regression findings from SP2 suggest that the ERM was a significant factor in explaining security returns but was found redundant during SP1. In

Table 9, the statistics for portfolios SMN, SMB, SLG, SLN, and SLB are not reported, as there were no securities in these categories. The analysis suggests that ERM, SMB, and HML factors were significant. The GMB factor was found to be significant in the portfolio of ‘Small’ stocks and ‘Good’ stocks. The dummy variable returned to being redundant, as its coefficient was statistically insignificant. This implies that the effect of pandemic was being captured by other factor(s). The significance of ERM factor also relates to the insignificance of the dummy variable. The pandemic also affected the market portfolio significantly, and thus, the dummy variable was rendered insignificant. Another interpretation for the dummy variable being insignificant can be attributed to the impact of government policing in India, such as demonetization and the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) law (

Mishra et al. 2020). The findings from

Table 10 have similar results. The findings of portfolios SMT, SMO, SLT, SLN, and SLO are not reported as there were no constituent securities in these portfolios. The significance of TMO factor was observed only in transparent and neutral stocks, with the coefficient being positive for transparent stocks and negative for opaque stocks. This is in line with the findings of

Henriksson et al. (

2019). Another observation is related to the model performance. The adjusted R-squared values were comparatively more significant for the model with the TMO factor.

Table 11 summarizes the GRS test statistics and associated

p-values for joint significance of (a) the FFTF model, (b) the FFTF and GMB model, and (c) the FFTF and TMO model for both SP1 and SP2. The results for FFTF model in SP1 show that the intercept was statistically significant, suggesting that the model was incorrectly specified, as it omitted key explanatory variables. The results for the FFTF and GMB model are not reported for SP1, as the data on ESG scores were not available during the period. The results for the FFTF and TMO models suggest that the regression intercept was jointly insignificant, and the model was correctly specified. The GRS test combined with the significance of the factor coefficient validates the use of the TMO factor in the asset-pricing models. The results for SP2 suggest that all three models were statistically insignificant, implying they were correctly specified. The low F-statistic for the TMO model suggests that it had more explanatory power than the FFTF model or FFTF + GMB models during SP2.

7. Conclusions and Implications

This study analyzed the role of ESG disclosure factor in explaining financial performance of index constituents of BSE 500 stocks. Using an asset pricing approach, long short portfolios were created on the basis of size, value, and ESG disclosure factors. Initially descriptive results were compared for portfolios formed on the above factors using univariate, bivariate, and trivariate sorting approaches. The descriptive results confirmed the presence of factors premiums. To explore further, time-series regressions were utilized to check the explanatory power of factor premiums. The study found a significant positive premium for size factor and significant negative premiums for transparency and value factors. Lastly, GRS test was employed to test the joint significance of the five-factor model, including excess market returns, size premium, value premium, disclosure premium, and a dummy variable for the COVID-19 pandemic effect on portfolios.

For establishing the robustness of the factors, the suggested model was compared with the FFTF + GMB model for a smaller study period. The GRS test statistics indicated that the intercepts were jointly insignificant, suggesting that the model significantly captured the variations in asset prices. The GRS test and higher adjusted R-squared values also confirmed that the model with the TMO factor had higher explanatory power than the model with the GMB factor. Finally, we found that excessive ESG disclosures by companies led to a negative risk premium in comparison with their non-transparent peers. We also highlight that the portfolio risk for opaque portfolios was significantly higher than that of transparent portfolios, implying that firms that do not disclose ESG information suffer the most in bearish market conditions against those that disclose.

The findings of this study have important implications. Firstly, the findings on ESG disclosure are important for ESG analysts, Chief Sustainability Officers (CSOs), Chief Financial Officers (CFOs), and other finance managers, as the government has mandated the top 1000 listed companies in the Indian capital markets to disclose ESG-related information from FY 2022–2023 (

Das et al. 2023). These companies need know-how on what, when, and how much to disclose to maximize their financial performance in capital markets. Secondly, the study is important for fund and asset managers, wealth advisors, and portfolio managers, as this discusses the role of ESG disclosure in the financial performance of a firm. This study faces the following limitations. Firstly, being the first study on using ESG disclosure as a factor in asset-pricing models, this study lacks solid theoretical establishment for inclusion of ESG disclosure premiums. Secondly, the concepts of sustainability and ESG are relatively new, and, thus, empirical data for most companies are not available for past years. Thirdly, the results of the regression in SP2 may also not be reliable due to the small sample size, and a portfolio allocation in triple-sorted categories may not have been justified. This study analyzed data of all the companies in the BSE 500 index with available ESG disclosure scores. The data for all companies are not yet available to date, indicating that not all companies are disclosing their data on ESG datapoints. Fourthly, the COVID-19 pandemic affected industries differently. One industry may have been more affected than another, and using a dummy variable will assume that the impact of the pandemic was of the same magnitude on all sectors. Therefore, scholars must come up with more robust methodologies to account for the seasonality or industry-wide factors. To take this study forward, scholars can utilize the ESG-related scores by other databases and compare their findings with this study. The challenges in disclosing ESG data should be explored further by the scholars. The findings of this study can be compared globally with similar countries using the asset-pricing approach, which will further help in generalizing ESG disclosure as a factor.