Abstract

This paper captures advances in prudential regulation and supervision for challenger banks and fintech in the UK. It presents a critical analysis of the prudential supervisory approaches towards fintech. The focus is placed on fast-growing firms (FGFs), building on the review performed by the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) of the Bank of England (BoE) in 2019. Specifically, it comprises a critical examination of the underlying regulatory framework in relation to the robustness of stress testing practices, as part of the review of FGF risk management practices and the weakness identified in the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP). The economic analysis of law comprises the underlying methodology, using economic theory to analyse regulation and its effectiveness regarding fintech regulation and supervision. Recommendations for enhancements towards supervisory practices about the prudential governance and management of FGFs and fintech are included, with advances to the underlying regulatory framework in the UK. Overall, this critical legal research examines the supervisory practices of FGFs and fintech in the UK, under the lens of prudential regulation and risk management approaches, focusing on the design, development and implementation of the stress testing tool and scenario practices.

1. Introduction

Financial innovation via the application of digital technologies has led to the rise of financial technology companies, denoted as ‘fintech’. ‘Tech firms whose core business focuses on using technology to deliver financial services either solely or primarily online’, based on Zamil and Lawson (2022, p. 4), comprises the adopted definition of fintech, with fintech engaging in financial services either via a focused activity or as part of a larger diversified firm. The activity, type of service and business model varies across fintech, however, there are a lot of similarities amongst them regarding their operations and strategies. A shared characteristic of fintech is the challenges introduced in relation to their prudential regulation and supervision, which is the focus of this paper. Described by rapid growth and constant innovation, they effectively test supervisors’ responses in catching up with the developments of fintech. Over the years, there has been a plethora of studies describing the evolving regulatory and supervisory approaches towards fintech, highlighting weaknesses, limitations and areas for improvements and enhancements. Nevertheless, there have not been any developments in relation to prudential risk management, specifically concerning stress testing.

Bridging this gap, this paper presents advances in prudential regulation and supervision for fintech at a UK level. Specifically, a critical analysis of the fintech supervisory approach is presented, commenting on the limitations identified from existing stress and scenario tests, concluding with the overall supervisory practices for the sound prudential supervision of fintech. The focus is placed on UK fintech and fast-growing firms (FGFs), building on the review conducted by the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and the Bank of England (BoE) of 20 non-systemic deposit-taking firms with different business models and activities (Beaman 2019). In particular, the underlying regulatory framework for the robustness of stress testing practices, as part of the review of FGF risk management practices and the weakness identified in the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP), are discussed.

This is based on the thematic review for non-systemic firms and the assessment performed for FGFs from the 2019 PRA study, aiming to ensure the resilience of the sector, testing for their governance and risk management capabilities (Beaman 2019). This is crucial, especially after the challenges introduced by the current coronavirus pandemic crisis (COVID-19). Therefore, this review highlights the importance of central banks and prudential regulators in monitoring the practices and processes of digitally transformed banks and in being the guardians of financial stability. This paper focuses on the important role of central banks in creating the protective binding regulatory environment to facilitate the digital transformation and digitalisation of banks, with special attention to non-systemic institutions such as the challenger banks and fintech. Extending the implications to supervisory practices, this research attempts to provide further insight and an assessment into the risk profiles and transmission channels of FGF. This is conducted via the design of stress tests and the ICAAP exercise, which is part of the supervisory review and evaluation process (SREP).

The economic analysis of law comprises the underlying legal methodology, using economic theory to analyse regulation and its effectiveness. This provides a framework for critical analysis on how regulation should be designed and reformed to ensure the financial soundness of the UK fintech and FGFs (Sanchez-Graells 2018, chp. 8, p. 171), highlighting the need of this proposed ‘economically informed’ legal research (Sanchez-Graells 2018, chp. 8, p. 171). The adopted view is that law can be used as an instrument directly to facilitate market developments and regulations, which is a natural inclination of policy makers (Black 2010, p. 164). Therefore, the results of this research in relation to policy and regulation contribute to evidence-based policy making in the form of a knowledge transfer for policy and regulation (Partington 2010, p. 1004–5). These evidence-based proposals of prudential regulation and fintech are based on results from the economic research conducted about existing supervisory practices for UK fintech and FGFs (Sanchez-Graells 2018, chp. 8, p. 171).

The paper is structured as follows: the PRA’s review of FGF is presented, capturing the key findings and associated regulatory developments. This is preceded by the depiction of the advances to prudential supervision for fintech, after describing the gaps and limitations in relation to the ICAAP, SREP and stress testing. The last part of the paper summarises the key findings, highlighting the recommendations towards sound prudential risk management for fintech at the UK level.

2. Prudential Regulation Authority Review

2.1. Findings

In 2019, the PRA published the key findings of the initial review conducted in relation to fintech and FGFs (Beaman 2019; Binham and Megaw 2019). This PRA assessment consisted of the review of 20 non-systematic deposit-taking firms with different business models and activities (Beaman 2019). The aim of the review was to test the financial resilience of FGFs and enhance the PRA’s knowledge of the funding and lending markets in which they operate (Beaman 2019). The three key elements of the review were the (1) ICAAP stress testing, based on the BoE’s published 2018 stress scenario (BoE 2018) that is the focus of this paper; (2) asset quality reviews; and (3) funding and lending analysis (Beaman 2019). Note that, despite their interconnectedness, this paper analyses only the first element of stress testing.

After looking at the individual returns and peer comparison, the PRA’s review provided reassurance about the overall resilience of the sector, highlighting certain weaknesses in risk management practices, underlining the importance of ensuring that governance and risk management capabilities remain aligned with the business model risk profile and risk appetite (Beaman 2019). In relation to stress testing, building on the 2018 market-wide macroeconomic stress test (BoE 2018), further improvements to stress analysis and stress management capabilities are required. The key areas of weakness are in relation to the underlying assumptions application, the understanding of the stress drivers and the sensitivity analysis to the business model and management actions (Beaman 2019). Commenting on the importance of robust governance in delivering sound stress testing, the effective engagement and challenge by senior management and boards, with stress testing integrated into the business, is flagged (Beaman 2019). Further work is required in relation to realistic and plausible management actions considered, consistent across the ICAAP and the systemic stress test (Beaman 2019). Overall, this review was very important for the prudential regulation and supervision for fintech in the UK, as it was a starting point for regulatory developments in that direction.

2.2. Regulatory Developments

The PRA’s approach to new and growing banks was launched in 2020, building on that review and the ‘Dear CEO letter’ from 2019 (Beaman 2019), in combination with the previous joint BoE and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) consultation on non-systemic UK banks (BoE 2014). This is captured effectively in the PRA’s consultation paper CP9/20 (PRA 2020a). In that consultation paper, the PRA sets out its proposed approach to supervising ‘new and growing’ non-systemic UK banks, based on the existing supervision and proposals about amendments (PRA 2020a). Feedback responses1 to the consultation shaped the PRA’s regulatory and supervisory approach to new and growing banks, documented in the policy and supervisory statements, referring to PS8/21 (PRA 2021b) and SS3/21 (PRA 2021a). This is inclusive of amendments to the ICAAP, SREP and stress testing2, with references to supervisory statement SS3/21 (PRA 2021a, 2021b). This is referring especially to amendments in the ICAAP SS3/15 (PRA 2020b), as well as to the PRA’s methodologies for setting Pillar 2 capital (PRA 2021a, 2021b).

However, are these amendments what is needed to ensure the sound prudential supervision of fintech? In this paper, it is argued that these developments are not sufficient to address the weaknesses and vulnerabilities identified in the 2019 PRA review, as they fail to capture the idiosyncrasies of fintech. PRA’s proposal in CP9/20 was targeting improvements in developing further stress testing capabilities, to ensure that fintech and FGFs are prepared for the transition to a PRA buffer3 set on a stress test basis4 (PRA 2020a). Specifically, section 5 from PS8/21 (PRA 2021b) and chapter 4 from the supervisory statement SS3/21 about non-systemic UK banks (especially paragraphs 4.16–4.20), provide an overview of the guidance in relation to stress testing as part of the ICAAP (PRA 2021a). Table 1 below captures the developments in relation to ICAAP as summarised in Table 2 (pp. 12–13) from SS3/21 (PRA 2021a).

Table 1.

PRA’s ICAAP expectations.

Recognising the evolution of the ICAAP and stress testing capabilities in that direction, these amendments could be linked to the regulatory threshold approaches compared to growth models for fintech (Arner et al. 2015), and the bank pre-authorisation journey from the PRA, as described in Section 3.3 below about the SREP. More guidance is available from the recently established “New Bank Start-up” unit at the Bank of England, providing further clarity in relation to regulatory expectations (BoE 2016, 2022; New Bank Start-Up Unit 2022). This consists of risk management assessment guidance with expectations in relation to capital assessment, where further insight on the ICAAP, stress testing and reverse stress testing is presented (BoE 2022).

3. Prudential Supervision of UK Fintech

What has actually changed in the ICAAP guidance from the PRA and supervisory statement SS31/15 is merely a reference (para. 5.25ZA) to those regulatory developments, referring to PS8/21 and to SS3/21 (PRA 2021c). However, considering the business model of fintech and FGF, as well as the associated risks introduced, further amendments should be considered in updating the ICAAP guidance. The gaps identified refer to limitations in existing prudential risk management practices, based on the ICAAP and SREP, and particularly about their common core element: the stress and scenario testing analysis. Consequently, enhancements to existing supervisory practices and to amending SS3/15 about the ICAAP/SREP are proposed (PRA 2021c). These are detailed in the following sub-sections, providing supporting evidence for the recommendations in the underlying regulatory framework.

3.1. Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process

The key risks of the business model, inclusive of ensuring sufficient capital and proportionate treatment to nature, scale and complexity of the fintech, are integral parts of the ICAAP exercise (BoE 2022). The ICAAP’s significance in fintech’s effective supervision underlines its important role. This highlights the need for developments to enhance existing practices. Therefore, starting with the recommendations about the ICAAP, more frequent updates should be performed in line with the business model developments of fintech (PRA 2021c, para. 2.1). This will allow capturing the changes to fintech’s risk profile and risk appetite in a dynamic setting, accounting for its underpinning strategy to explore the market and grow. In that direction, an agile and flexible framework for stress testing, scenario analysis and capital management should be designed, developed and implemented, to reflect the evolving risk profile and nature of fintech (PRA 2021c, para. 2.5). Severe but plausible scenarios addressing the key risks of fintech and FGF should be included in the ICAAP, explaining how stress testing supports their capital planning processes and business strategy setting (PRA 2021c, para. 2.5).

Beyond the standard risks of financial nature, such as market, credit and liquidity, risks introduced by the operations of fintech of non-financial nature should also be examined under stressed conditions, capturing their transmission channels as well. An extension of regular stress testing of the business continuity plan in an appropriate and proportionate manner to focus on the financial risks, as well as cyber and operational risks, (PRA 2021c, para. 2.19) is proposed. Consequently, operational risk scenarios with an assessment of their impact and likelihood should be included (PRA 2021c, para. 2.20). On that basis, scenarios about business continuity (and disaster recovery) for operational risks should compose a core part of the ICAAP (PRA 2021c, para. 2.19). Therefore, looking at amending chapter 2 of the ICAAP guidance, the focus should be placed on the frequency of this exercise, described by flexibility, being dynamic to business model updates and extended in capturing the key risks of non-financial natures and cyber and operational risks, stemming from fintech’s operations and strategy. An overall pragmatic SREP5 should be considered (PRA 2021c, chp. 5) with a dynamically adjusted ICAAP that consists of stress and scenario tests of an exploratory nature, conditional on the growing stage of fintech.

3.2. Stress Testing

The key to realise the ICAAP/SREP improvements to ensure the sound prudential supervision of fintech is stress testing. This is central to the Basel III framework, with the use of stress tests in the capital adequacy assessment for economic downturns, market-risk events and liquidity conditions (BCBS 2017, para. 202–5). Amendments with practical application about the scope, time horizon and risks considered for the different types of scenarios should be introduced. This would effectively amend the PRA rulebook (PRA 2022, chp. 12) in the scope of the Capital Requirements Regulation6, capturing also severity, likelihood, modelling parameters and the overall methodological approach. These refer to stress testing, scenario analysis and capital (PRA 2021c, chp. 3), with reverse stress testing (RST) (PRA 2021c, chp. 4) as in Basel III (BCBS 2011, p. 115, para. 56).

Especially in relation to the risk management tool of stress testing that comprises a core element of the ICAAP and the SREP (PRA 2021c, chp. 3), amendments should be incorporated in relation to the timeframe, risks considered, governance and modelling. Scenarios and sensitivities should be explored in the short- and medium-term within the business plans produced, in order to understand changes in capital needs (PRA 2021c, para. 3.4). The stress tests examined should cover the key financial and non-financial risks (PRA 2021c, para. 3.6). Their results should be used to support setting business strategy and informing the risk appetite, evidencing senior management/board engagement and challenge (PRA 2021c, para. 3.7, para. 3.11), based on findings of the PRA’s initial review about governance (Beaman 2019). Stress tests should be carried out more frequently than annually, and actually performed every time the business plans are updated, with scenario recalibration (PRA 2021c, para. 3.8, para. 3.13). This flexible and dynamic set-up of scenario analysis, with regular updates in a segmented modelling horizon, allows for matching the business plan developments with frequent recalibrations for the results’ validation. Short- and medium-term projection of the business plan and capital resources/requirements, under shorter horizon segments such as splits of 0–1 year, 1–3 year and 3–5 year intervals (PRA 2021c, para. 3.9), should be incorporated into the stress testing and scenario analysis. Beyond this segmentation, stress testing should be forward-looking with a multi-year risk assessment (PRA 2021c, para. 3.22) and linked to risk appetite to reveal the key vulnerabilities in the fintech’s capital profile (BoE 2022). A proportionate approach should be followed for the stress testing of fintech based on regulatory guidance to ensure adherence to the Capital Requirements Directive7 (PRA 2020c, 2020d).

The replication of regulatory-prescribed stress and scenario tests is another recommendation to support the internal stress testing practices. Lessons from those exercises should be embedded in their internal framework, supporting the design and development of idiosyncratic stress and scenario tests. Regulatory developed scenarios, referring to the ones prescribed by the BoE/PRA, such as the annual cyclical scenario (ACS) and the concurrent solvency stress test (SST) for the systemic banking institutions (Dent et al. 2016), should be considered as a guide, and performed as a benchmark. The PRA’s expectation is that own scenarios should have the same severity as the concurrent stress test (BoE 2022). A simplified approach and quantification of those stress tests is recommended, being also advisable to attempt replicating additional exploratory scenarios by the prudential supervisors. For instance, the Liquidity Biennial Exploratory Scenario (LBES) for liquidity risks and the cyber stress test from the BoE’s Financial Policy Committee (FPC 2021) are additional regulatory prescribed scenarios that could be considered and examined. Additionally, how the risks examined under stressed conditions are interlinked to operational resilience and impact tolerances (Strange 2020).

In relation to the PRA capital buffer that is currently based on a wind down cost calculation, a simplified approach for its calculation is proposed (as 6 months operating expenses instead) with the bank moving onto either a buffer set on a stress test basis, five years post authorisation, or when they reach profitability, whichever is sooner (PRA 2020a, para. 2.3). This highlights the need for banks to develop their stress testing capabilities further, following growth and maturity post authorisation, to ensure a smooth transition to a PRA buffer set on a stress test basis (PRA 2020a, para. 2.4). Considering that a severe but plausible stress scenario is used for the PRA buffer calculation (PRA 2020a, para. 3.5), advances in the internal stress testing framework and capabilities of fintech will support the preparations for the PRA buffer calculation.

The recommended amendments to the PRA’s ICAAP guidance in relation to stress testing, scenario analysis and capital planning (chapters 2 and 3) (PRA 2021c) are presented in the following table (Table 2).

Table 2.

PRA ICAAP Guidance Recommendations8.

3.3. Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process

After describing the recommended amendments to the supervisory guidance with a focus on stress testing, some further proposals are listed below, based on the literature for regulating fintech in relation to the SREP, requiring tailored methodologies (PRA 2020c). The SREP comprises a core supervisory activity which consists of looking at the business model, governance and risks, capital/liquidity requirements, management of risks, and resolution plans for identified vulnerabilities, thus being important foreach fintech (EBA 2014, 2022; ECB 2022). Under the SREP process, the PRA reviews and evaluates further risks revealed by stress testing (PRA 2021c, chp. 5). Building on the joint FCA and PRA regulatory guidance for new bank start-ups in the UK (BoE 2022), the regulatory sandbox (FCA 2015) comprises a practical approach in embedding these recommendations in relation to the SREP and ICAAP, concerning stress and scenario testing. Supervisory support, focusing on other dimensions beyond the ICAAP, such as the Internal Liquidity Adequacy Assessment Process (ILAAP) and recovery and resolution planning (RRP), should be placed as a key priority for the PRA. A pragmatic SREP should be followed, with enhanced ICAAP, stress testing and scenario analysis, with reverse stress tests approaches, accompanied by a Pillar 2 PRA buffer calculation. Scenarios to capture orderly exit (recovery and resolvability) with updates to recovery and resolvability (RRP) and liquidity risk management (ILAAP) should be performed by fintech and FGFs. This is linked to the risk appetite integration in the ICAAP/ILAAP recovery and solvent wind-down (SWD) plans9 (BoE 2022).

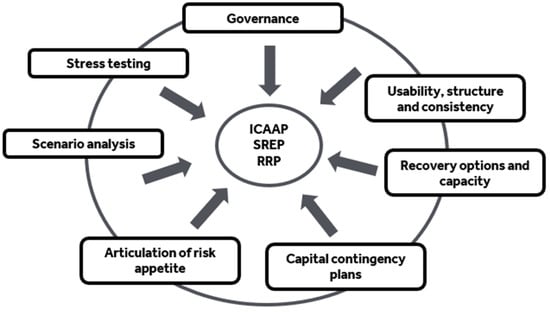

Regulating fintech via a guided sandbox10 (Ringe and Ruof 2020) could facilitate the step-by-step improvements in the underlying prudential framework, while ensuring supervisory support, towards a more flexible and sounder regulatory ecosystem, constituting the basis of an adequate regulation of fintech. A regulatory sandbox would support fintech, understanding the lack of sufficient regulatory expertise from a fintech’s perspective (Ringe and Ruof 2020). However, the sandbox approach has limitations, with certain threats still prevailing, such as cyber risk management maturity (Ringe and Ruof 2020). The regulatory sandbox as an approach to fintech regulation has been accused of ‘risk-washing’, lacking transparency, not capturing fintech’s risks appropriately, and, consequently, not controlling for systemic risk (Brown and Piroska 2022). Utilising the UK regulatory sandbox (Gerlach and Rugilo 2019), referring to the FCA’s regulatory sandbox (Hodson 2021) to support background work as preparation for prudential supervision (FCA 2015) will ensure a smooth transition towards the ICAAP, SREP and stress testing recommendations, as captured in this paper. The regulatory sandbox approach could also be further enhanced with the implementation of a “scalebox”, as proposed by Kalifa (2021, p. 35), for the support of fintech. The PRA’s New Bank Start-up Unit (NBSU) joint approach with the FCA could drive these fintech supervisory advances, with amended guidance based on the common challenges in relation to the ICAAP identified as depicted in the following figure11 (Figure 1) (BoE 2022). These common challenges reflected in the ICAAP practices and recovery plans constitute a core element of the PRA’s supervisory assessment, underlining their importance for adjustments (BoE 2022). Stress and scenario testing comprises a common theme in the regulatory requirements and supervisory expectations underpinning the ICAAP, SREP and RRP, as demonstrated by the following figure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The PRA’s regulatory expectations and challenges.

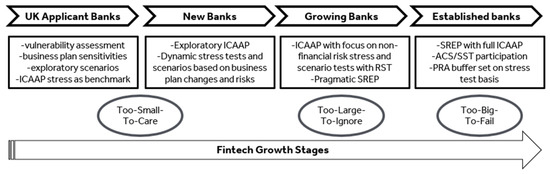

In that direction, the prudential supervision of fintech, based on its growth stage and the PRA’s regulatory expectations as part of its pre-authorisation journey, is graphically depicted in the following figure12 (Figure 2). It is proposed that the ICAAP and stress testing with a pragmatic SREP evolve in line with the bank pre-authorisation journey, with supervisory support via the regulatory sandbox. Additionally, ICAAP and stress testing should be based on the fintech’s growth stages that determine the internal practices and their links to business plans, risks and strategy. Building on the regulatory threshold approaches compared to growth models for fintech from Arner et al. (2015) (bottom part of Figure 2 below), in conjunction with the PRA’s journey of a bank from pre-authorisation to an established bank (PRA 2021a, 2021b) (upper part of Figure 2 below), stress testing capabilities and ICAAP expectations should evolve. This approach will support fintech during its growth stages and authorisation steps (Arner et al. 2015).

Figure 2.

Fintech regulation during growth stages and banking authorisation.

Effectively, an extension of the regulatory perimeter, with a pragmatic approach tailored to evolving business models and the associated risks of fintech/FGF (Enria 2018), is proposed. That way it will allow the assessment of risk profile and transmission channels, whilst capturing their risk interconnectedness (Crisanto et al. 2021). The regulatory framework with perimeter expansion supports the identification of new and emerging risks, with their transmission channels impacting the real economy (Van Steenis 2019). Especially considering cyber and operational risks, with their implications to operational resilience. In turn, this focus on operational resilience serves as the structure of a more balanced regulatory framework (Crisanto et al. 2021; Carstens 2021; Carstens et al. 2021). The operational resilience of regulating Big Tech in finance is highlighted by Ehrentraud et al. (2022, Table 3), with supervisory measures for operational resilience and the effective management of cybersecurity risk captured in the IMF’s report (2019). These explain the importance of testing fintech for those risks, via the ICAAP and stress tests.

The ‘pragmatic SREP’ recommended which is aligned to Kalifa’s recommendation to adjust fintech regulation based on the size and growth of the fintech (Kalifa 2021, p. 37). Especially during the growth stage and as clarified in the expectations set out in the Bank of England’s New Bank Start-up Unit guidance (BoE 2016, 2022; Kalifa 2021). The ICAAP and stress testing developments are based on the regulatory threshold approaches compared to growth models for fintech (Arner et al. 2015) and the bank pre-authorisation journey from the PRA. These developments should evolve to match fintech’s growth, updated in line with fintech’s strategy. Ensuring that regulation is the “right size” is highlighted in Kalifa’s review, with the prudential regime adjusted for the size and growth of the fintech (Kalifa 2021, p. 37).

3.4. Prudential Risk Management of Fintech

Some concluding remarks are offered about the design and development of stress tests and scenario analysis by fintech and fast-growing firms. These reflect the weaknesses identified describing fintech, i.e., the PRA’s supervisory approach and its limitations, based on their risk profile for their prudential risk framework development. In particular, this focuses on looking at new banks13 and their associated risks characterised by rapid growth, loss making, reliance on regular capital injections, and significant and rapid changes in strategy and business model, with immature controls (PRA 2020a). Consequently, stress tests should be developed to capture and test those risks.

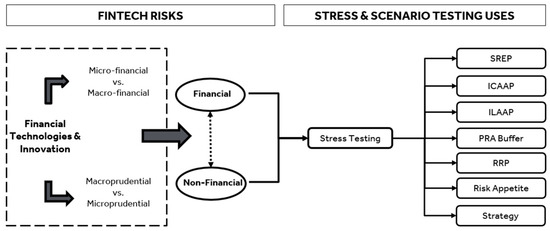

The design and development of stress and scenario testing should be enhanced, focusing on the key risks arising from financial technologies and digital innovation, with an emphasis placed on operational resilience (BCBS 2018). Fintech and FGFs should be developing their idiosyncratic stress and scenario tests further. These tools for micro- and macro-prudential purposes should cover key risks of technological innovations linked to financial intermediation of a micro- and macro-financial nature (e.g., cyber, data quality and data protection, etc.) (FSB 2017; Fáykiss et al. 2018). The key risks associated with the business model and operations of fintech and FGF should be incorporated into the regulatory framework, becoming part of the ICAAP, SREP, RRP and stress testing. These are operational risks from third-party service providers, mitigating cyber risks, monitoring macro-financial risks, and the governance and disclosure of frameworks for big data analytics (Weber and Baisch 2018). Strategic, operational, cyber and compliance risks are the key risks identified for incumbent banks and new fintech entrants into the financial industry (BCBS 2018). Financial risks capture leverage, maturity and liquidity mismatches, whereas operational risks refer to governance/process control, cyber risks, third-party reliance, legal/regulatory risk and business risk based on the Financial Stability Board (FSB 2017). The risks from financial technologies and innovation (BCBS 2018, graph 6) are segmented by their impact on the consumer sector14, banks and the banking system15. Fáykiss et al. (2018) presented the risks of technological innovations related to financial intermediation. These risks are split in micro-prudential risks, relating to increased funding risks linked to fintech’s leverage and asset-liability mismatch and operational and cyber risks (FSB 2017; Fáykiss et al. 2018). The stress tests developed and performed for fintech-specific scenarios should capture those risks, their associated risk drivers and their transmission channel, reflected in supervisory exercises.

Operational risks could be reduced with fintech developments as legal systems are modernised, and their processes streamlined (FSB 2017). Yet, cyber-risk, third-party dependencies and legal uncertainty could lead to new and expanded sources of operational vulnerabilities (FSB 2017). Regulation should be adapted to transformations of the financial sector characterised by the digitalisation and proliferation of cyber risks (Beau 2022). Reliance on technology and digitalisation amplifies cyber risks such as system vulnerabilities, cyber incidents (cyber-attacks, fraud) with operational implications (systems failure), and the introduction of complexities into regulatory approaches (FSB 2022). Managing operational risks from third party service providers, mitigating cyber risks, with information and cybersecurity planning, and the macro-financial risks emerging from fintech activities, compose key supervisory priorities highlighted by the Financial Stability Board (FSB 2017; Van de Wiele 2018). Scenarios focusing on operational risks based on each fintech’s risk profile should be examined to support both its operational and financial resilience. In that direction, scenarios such as system failure, data loss and cyber-attack are examples usually considered for those operational risks. In relation to the underlying regulatory framework, amendments to the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) are made in the 2021 EU Banking Package, introducing operational risk and information systems and communication technology risks16 linked to cyber risks and the key risks arising from fintech EC (2021a, Article 1). This is also linked to the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD) about the management of operational risks in own funds (EC 2021b, p. 84). The recommendations presented in this paper are in line with the CRR, CRD and the recent conducted review that formulated the 2021 EU Banking Package.

The regulatory focus towards adjustments in the underlying framework, aiming to respond to the new risks linked to technologies and innovation, and their overall use, describing fintech’s activities, should be highlighted (Saporta 2018). Certain new risks introduced by fintech, such as data protection-related risks, are captured in the IMF’s report (IMF 2019, Box 3). Data quality and data protection, with their associated risks linked to fintech operations and innovations, which involves the use and analysis of large data sets, compose another source of micro-prudential risks (Fáykiss et al. 2018). In that direction, cyber risk exposure is also amplified stemming from the IT systems/software from the digital technologies employed by fintech (Fáykiss et al. 2018). However, the macro-prudential risks and systemic implications that fintech pose, strengthening the procyclical operation of the financial sector (Fáykiss et al. 2018), highlight the importance of developments in their prudential supervision. Key risks with links to financial stability are micro-financial risks and macro-financial risks17, referring to contagion, pro-cyclicability, excess volatility and systemic importance (FSB 2017). The risks associated with financial technologies and innovation, segmented into financial vs. non-financial based on their nature and interconnectedness, should be examined under stress and scenario tests for different uses. The following figure (Figure 3) depicts the link between fintech’s risks and the uses of stress and scenario testing. These amendments, as described above, refer to stress and scenario testing as part of the ICAAP/ILAAP, SREP and RRP, with their output used to support setting risk appetite and strategy, as well as the PRA buffer calculation.

Figure 3.

Fintech risks and stress testing uses.

The empirical evidence obtained from annual report and accounts and, most importantly, from the Pillar 3 disclosures of each fintech, validate the above recommendations., Despite the progress observed in the risk management capabilities from the fintech’s Pillar 3 reports, as they started mentioning stress and scenario tests initially, before the actual reporting of the scenarios quantified and their assumptions in the more recent disclosures. This involves looking at the recent (past three to five years) reports of ClearBank, Atom, Monzo and Starling Banks18 for instance. The evolution of the prudential reporting, in terms of quality and quantity, reveals both the progress in internal risk management capabilities within fintech, and the importance of stress and scenario testing analysis at the same time, with its different uses as depicted above in Figure 3. This is partly driven by the regulatory framework and requirements, and their growth, corresponding to differences in banking authorisation and license. This explains the reporting and disclosure of prudential natures that are evolving, with certain fintech publishing annual reports with financial statements and Pillar 3 disclosures, while, at the same time, performing internal stress and scenario tests with ICAAP and ILAAP exercises, which are not publicly disclosed, with that information available only directly from the BoE/PRA and each fintech of course. The following table (Table 3) captures the information about prudential risk management practices as reflected in the disclosures of selected UK fintech banks19. It provides an overview of the activities performed by fintech as a checklist, along with the year first reported, captured in the parenthesis.

Table 3.

Empirical Analysis—Fintech Disclosures.

Information around stress and scenario testing is included in the annual report and accounts and in the Pillar 3 disclosures. However, often the information around stress and scenario testing is of a qualitative nature, explaining the internal approach as part of risk management practices, the overarching framework, and how the regulatory requirements are met (e.g., Pillar 2b PRA buffer, IFRS 9 for instance (IFRS 2022)). Additionally, there are differences in the level of detail presented for each scenario, and also in the scenarios performed, not allowing their comparison between each fintech. Therefore, there is no uniform information disclosed regarding the exact stress and scenario tests performed. Furthermore, the scenarios examined do not capture all risks, and especially the non-financial operational risks mentioned in the paper, instead focusing on credit and financial risks. The above are observed from looking at the disclosures from the annual and Pillar 3 reports from the selected UK fintech banks. Stress and scenario testing is employed for different types of risks, to support the going concern statement, the risk appetite development and as part of risk mitigation and control. Also, it is referenced as an integral component of the ICAAP, ILAAP and RRP. From the disclosures examined, it is clear that stress and scenario tests are performed, although, it is not always transparent which of them are quantified, and, most importantly, what their results are. The link of stress and scenario testing with the underlying regulatory requirements and risk management practices is consistent and coherent. However, only certain disclosures include in detail the actual stress and scenario tests, their assumptions, how they are quantified, the obtained result under stressed conditions and the available management actions. These findings are summarised in the following table (Table 4), presenting highlights from stress and scenario testing disclosures.

Table 4.

Empirical Analysis—Fintech Disclosures: S and ST.

Arguably, a more detailed empirical analysis of the fintech stress and scenario testing disclosures could be employed to complement the above recommendations and attest their validity, as highlighted in the limitations noted in this study. Nevertheless, insights from fintech of smaller size and operations, with no requirements for Pillar 3 disclosures, where this study focuses most importantly, cannot be captured empirically due to the lack of (publicly) available data.

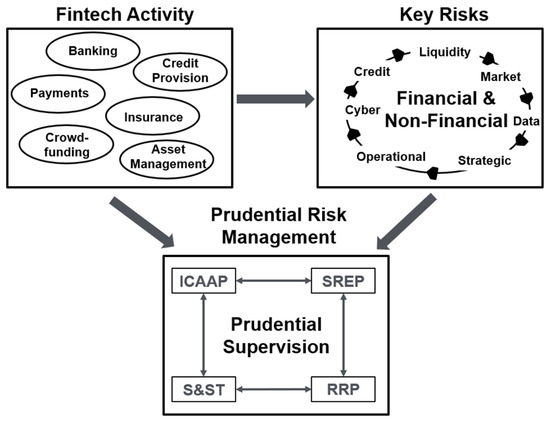

3.5. Fintech Activity-Based Regulation

Considering the similarities between Big Tech in finance and fintech, the regulatory approach for fintech is characterised by common themes. Therefore, a disciplined and consistent approach to regulate similar activities undertaken by different institutions that give rise to the same financial stability risks is observed (Carney 2017). The emphasis should be placed on the prudential requirements for regulating Big Tech, with the need for a new regulatory framework for financial soundness highlighted (Ehrentraud et al. 2022). The risk profile assessment and the risk transmission channels should be documented and captured in the ICAAP and the SREP (Crisanto et al. 2021). Initially, starting with sector-specific financial and non-financial risks, the risks from the financial system interconnectedness, and then moving to the risks arising from third-party services and partnerships with traditional financial institutions (Crisanto et al. 2021). To address this effectively, a bespoke policy approach for fintech should be adopted, enhancing the existing supervisory framework, focusing on activity-based (AB) regulation to capture the fintech activity specific risks, their systemic implications and their inter-linkages (Crisanto et al. 2021). This AB regulation20 allows for the creation of a more balanced regulatory framework (Restoy 2021a, 2021b). For instance, there are differences in relation to the fintech regulation with respect to asset management, crowd-funding and virtual currency (Magnuson 2017). These differences should be accounted for in the SREP, the ICAAP/ILAAP and stress testing to address the risks introduced and their associated transmission channel.

This is also linked to the risks connected with Big Tech activities in finance that are not fully captured by existing regulatory practices (Crisanto et al. 2021). The fintech business model, similar to the financial service offerings of Big Tech companies in banking, credit provision, payments, crowd-funding, asset management and insurance (Crisanto et al. 2021), should drive the ICAAP and SREP developments, with a tailored approach for each fintech. This effectively building tailored scenarios based on the business model and activity of each fintech21, incorporating the range of financial and non-financial risks, following the figure adapted from Crisanto et al. (2021) (Figure 4). Effectively, the business model and activity determine the risk profile of the fintech, with the associated key risks and risk drivers. The combination of the risk profile with activity shapes the prudential risk management components and exercises as part of the prudential supervision requirements and expectations. This relationship underpins the development fintech-specific stress and scenario testing, as depicted in the following figure (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Fintech risks prudential risk management.

This leads to updating the ICAAP, SREP and RRP, accordingly, based on those stress and scenario tests. Tailored scenarios and components of the ICAAP, based on the business model and financial services offered22 (banking, credit provision, payments, crowdfunding, asset management and insurance) (Crisanto et al. 2021), contribute to their prudent risk management and sound supervision. In effect, different risk drivers and parameters should be considered when designing stress and scenario tests to perform, based on the fintech activity. For instance, stress tests on liquidity and credit risks for a payment fintech might be more significant, whereas for an asset management fintech a market risk stress test might be more appropriate. In the same way, scenarios capturing underwriting risks could support the identification of weaknesses in the business models of insurance fintech (also referred to as insurtech). Arguably, there are similarities between scenarios capturing the key financial and non-financial risks for fintech’s based on their activities and business models. Nevertheless, the associated risk drivers and transmission channel diverges and should be properly accounted for when designing and examining sensitivities, scenarios and even reverse stress tests. This is in reference to both financial and non-financial risks, since the exposure and interconnectivity between those risks is shaped by the overarching risk profile of each fintech. Beyond the financial risks, since there are stress tests on market, credit, liquidity and insurance risks that have been developed by the prudential supervisors for systemic institutions (e.g., BoE’s ACS and SST), the idiosyncratic operational and strategic risk scenarios should highlight the differences on fintech’s activities and operations. These scenarios, linked to the business model and underlying assumptions (e.g., growth, licensing, competitive forces, etc.), are important in guiding their prudent supervision. This form of AB regulation in relation to stress testing could be considered vital for fintech, allowing it to further develop and improve its risk management capabilities (Borio et al. 2022). That type of regulation is associated with the fintech types, and how fintech is changing the financial system was presented by Mnohoghitnei et al. (2019, Figure 3). However, a combination of AB and EB regulation could also be considered, as it allows the realisation of the recommendations proposed for advances to fintech’s prudential supervision (Borio et al. 2022). Especially considering that these amendments are more in line with EB regulation, such as stress testing (Borio et al. 2022, p. 4 Table 1).

4. UK Fintech Regulation: Fit for Purpose?

Prudential regulation and financial stability comprise the key mandates of regulatory objectives and thresholds23 (Arner et al. 2015). Fintech creates new financial intermediation, challenging existing regulatory practices (Aaron et al. 2017). Regulatory developments are necessary to lead towards innovative outcomes in fintech and digitalisation, focusing on driving the digital evolution of financial services. This requires a conducive regulatory innovative framework to enable and facilitate the banks’ digitalisation, and to ensure its prudent supervision. This supports the validity of the recommendations presented in the previous section. Fintech’s rapid pace of change makes it more difficult for authorities to monitor and respond to the risks introduced to the financial system (FSB 2017). Regulators should remain relevant in the digital age, with updated tools under the same regulatory and prudential objectives during the fast-changing environment that characterises fintech (Anagnostopoulos 2018). Decentralised financial technologies challenge existing regulatory practices and financial supervision, requiring amendments (FSB 2019), as covered in the previous section of this paper, and summarised in the following table showing the proposals for developments in supervision, regulation and S and ST activities of fintechs (Table 5).

Table 5.

List of Recommendations for Fintech Prudential Supervision.

Fintech poses challenges to financial regulation regarding systemic risks spread in the financial sector (Magnuson 2017), with elevated prudential risk factors (Zamil and Lawson 2022). These challenges are associated with fintech’s structure, making it difficult to monitor their behaviour (Magnuson 2017). For this reason, banking supervisors need to adapt to technology and its associated risks (Proudman 2018). The coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated certain risks related to fintech, in particular linked to their nature and source of funding (FSB 2022). Regulation has failed to address certain risks from the rise of fintech (Magnuson 2017), evidently based on the PRA’s FGF study from 2019. Therefore, the current gaps in the effective prudential supervision of fintech, with the main focus on stress testing, arise from the combination of the difference in scale, size and maturity of risk management practices for fintech, but, also, because of the developments in their risk profile and risk universe part of their ICAAP (Gualandri 2012, p.76). New and emerging risks associated with fintech require ‘dynamic adjustments’ in the regulatory environment required, as the Executive Director for Prudential Policy of the Bank of England stated in a previous speech (Saporta 2018). This has also been highlighted by the IMF, regarding the review of existing legal and regulatory frameworks for fintech’s risk mitigation (IMF 2019). These capture amendments in the fintech’s institutional framework arrangements, policies, supervision and development (IMF 2019). The recommendations presented in this paper, as detailed above, match item 6, ‘Adapt Regulatory Framework and Supervisory Practices for Orderly Development and Stability of the Financial System’, from the IMF’s Bali Fintech Agenda (BFA) (IMF 2018, p. 8; 2019), confirming their validity. The rest of the BFA items are also linked to the recommended advances to the prudential framework and supervision of fintech. For instance, safeguarding the integrity of financial systems (agenda item 7) and the legal framework modernization (agenda item 8) (IMF 2018, 2019).

5. Conclusions

This paper attempts to provide practical recommendations to ensure the current regulation of fintech remains appropriate, applicable and effective (FSB 2019). These recommendations are closely linked to the Van Steenis (2019) report, with recommendations to increase finance’s resilience24. Potential threats to the new regulatory framework on payments, with increased operational risks, security risks, fraud- and data protection-related risks from customer data analysis, and sharing with third-party providers via digital applications, are also flagged (de la Mano and Padilla 2018). This example about the risks originating from specific fintech activities could be generalised for the rest of fintech. Using the case of challenger banks in the UK, after an FCA review about risk assessment, customer risk assessment frameworks were found not to be developed and lacked sufficient detail, with some not having risk assessments in place (Rusch 2022). Forward-looking judgement-based supervision to identify the key risks and set supervisory strategies for their effective mitigation is needed for fintech (Proudman 2018). The pragmatic approach for the ICAAP, SREP and stress testing is echoed in Andrea Enria’s speech, arguing against an excessive extension of the regulatory perimeter to attract fintech under the scope of bank-like supervision, with that approach not being an optional solution to harnessing financial innovation (Enria 2018). Thus, effectively, the proposals stemming from this analysis of fintech stress testing practices are closely aligned to the policy and regulation recommendations captured in Kalifa’s review25 about the ‘new regulatory framework’ (Kalifa 2021). How should these developments actually materialise? There are formal options with developments in the regulatory framework, with updated guidance from the Bank of England and the PRA. This means that the consultation paper, policy and supervisory statements required to be amended, with their developments reflected in the respective rulebooks. Nevertheless, an informal approach via the regulatory sandbox and “scalebox” could potentially be sufficient, on the basis of providing further support and under the Periodic Summary Meeting (PSM) to back test these recommended amendments (Kalifa 2021).

Beyond the regulatory developments described, examining the supervisory collaboration is also proposed, referring to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) and their interaction with the PRA/BoE and the FCA towards the prudent supervision of fintech (FSB 2022). It is in this context that stress testing practices could be enhanced, with regulatory prescribed stress and scenario tests for fintech developed jointly by supervisors comprising a solution to trigger the development of internal fintech practices and drive forward the implementation of the ICAAP improvements. For instance, the collaboration of supervisors for scenario development and implementation, looking at different angles, with key risks and their transmission channels reflected in a combined stress test for fintech, is suggested. In a different direction and in addition to the UK regulatory environment, cross-border legal issues and regulatory arrangements with the frequent regulatory perimeter assessment (FSB 2017) are recommended. Additionally, this should coincide with the EU harmonisation at a legal and regulatory level to account for the fragmentation of fintech regulation (Van de Wiele 2018). Managing operational risks from third-party service providers, mitigating cyber risks and monitoring macro-financial risks constitute priority areas for international cooperation for the fintech regulation (FSB 2017), supporting the supervisory amendments proposed26.

The findings of this paper add to the literature on the impact of financial technology and innovation to prudential supervision and regulation about the role of prudential regulators and supervisors to ensure the smooth transition of financial institutions in the digital era. The results of this research, in relation to policy and regulation, contribute to evidence-based policy making in the form of a knowledge transfer, focusing on enhancements of risk management practices and supervisory developments in the area of stress testing (Partington 2010, p. 1004–5). This is realised by extending this analysis on the risk assessment integration into the SREP (EBA 2014, 2022), the ICAAP practices (PRA 2021c, SS3/15) and the stress testing exercise under the regulatory framework (Basel III, CRR II, CRD V) as in PRA’s CP12/20 (PRA 2020c, 2020d).

Certain limitations describing this study should be noted, interlinked with the extensions and directions of further research. These limitations underpinning this study capture the methodological approach and nature of recommendations presented. The most apparent limitation is the empirical analysis of this study at its infancy, considering the lack of data publicly available, as described above. Stress and scenario testing data are not available for all fintech, neither is it provided in an aggregate format by the BoE/PRA, since there are no fintech-specific stress tests. Information from the Pillar 3 disclosures is insightful, revealing the developments around stress testing capabilities and scenarios performed, though currently is neither complete nor uniform in its level of detail to allow their comparison to extract inference. Furthermore, considering that the initial PRA’s review (Beaman 2019) is not publicly available to show the exact 20 FGFs examined, there is going to be an inconsistency if the empirical component of certain firms captured that perhaps were not included in the initial review. In that direction, disclosures and statements for key fintech in the UK are available for the most recent reporting periods (the past two to four), thus not all information from the period of the initial review is available. Moreover, not all fintech are required to complete/publish Pillar 3 Disclosures, where perhaps the findings of this study are more appropriate, and thus are not going to be included anyway in the empirical analysis due to the lack of available data. Following from the empirical component, another limitation is the validation of the recommendations presented. This could be conducted by incorporating the view from prudential supervisors, based on the historical ICAAP exercises completed, the SREP activities, and the results of the stress and scenario tests completed, highlighting on the findings observed from these evolving processes. In that direction, striking the right balance between regulatory expectations from the supervisors with the internal processes, capabilities, and skills of the fintech is key. This could help understand the efficacy of the recommendations presented from the fintech practitioners responsible for performing the stress and scenario testing exercises and, in general, embedding the enterprise risk management framework and risk models. The associated people related risks characterising the risk management capabilities of fintech are a major risk not captured directly in this study.

Cognizant on these limitations, this research could be extended in different directions. Initially, it could be extended by examining fintech regulatory developments at different jurisdictions, starting at the European level and, then, across the globe. Building on this this, it could focus on other aspects of fintech regulation beyond prudential supervision, expanding from the activity-based regulation with case studies from the UK and/or globally focusing on different types of fintech (e.g., Monzo Bank, Klarna, etc.). The empirical component could be a different addition, using financial information and disclosures from fintech in relation to risk management practices and stress testing. This is a limitation underpinning this study, on the basis of data not being publicly available, neither on a fintech basis or on an aggregate level from the BoE/PRA. Conducting interviews with representatives from the risk management functions of fintech to provide insights and the practitioner’s view on the applicability of the recommendations, as well as with fintech supervisors, comprises another angle to validate the proposals discussed. Another angle of a possible extension could be linked to the use of data in shaping regulation, as in the Bank of England’s response to the Van Steenis review (2018) on the Future of Finance (BoE 2019). Embracing regtech to support the effective regulation of financial services, with the use of data innovation and capabilities from supervisors, could also be consider as another avenue to support the recommendations presented in this study. (BoE 2019; UNSGSA 2019; Barefoot 2020). Ultimately, the proposals discussed in this paper contribute towards the resilience of the financial system, as denoted by priority 4 and 5 of the Bank of England’s response to the Van Steenis review (2018) (BoE 2019), explaining that potential link with directions for further research.

Recommendations for enhancements towards supervisory practices about prudential governance and management of FGFs and fintech are included, with advances to the underlying regulatory framework in UK. Extension at a European level should also be considered, capturing the evaluation of the adoption of the 2021 banking package with revised rules on capital requirements and directives (CRR II/CRD V) (EC 2021a, 2021b). This specifically refers to advances in prudential supervision and proposals for the development of supervisory tools for the effective management of fintech as part of the SREP with Pillar 2 requirements, such as stress testing as described in this paper.

Overall, this research examines the supervisory practices of FGFs and fintech in the UK, under the lens of prudential regulation and risk management approaches, focusing on the design, development and implementation of the stress testing tool and scenario practices. This study contributes to the advances of prudential regulation and supervision for fintech. The author has attempted to add to the growing literature about fintech and risk management practices, with an examination of stress and scenario testing capabilities following a recent PRA study (Beaman 2019). However, cognizant of the challenges introduced by fintech based on their activities and risk profile, further advances, and developments in that area, led by supervisory authorities are required, as documented in this study.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the University of Reading.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the feedback received from the attendees of the “Technology, Innovation and Stability: New Directions in Finance (TINFIN)” 2022 International Scientific Conference, the 2022 Cryptocurrency Research Conference (CRC) and of the 6th European Centre for Alternative Finance (ECAF) and COST Research Conference 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | PRA’s consultation papers (CP) are published with request for input. After incorporating feedback received, an update is produced that is usually translated into the updated policy statements (PS) and supervisory statements (SS). |

| 2 | Bank of England’s guidance regarding stress testing with the regulatory prescribed scenarios is captured in further detail in Dent et al. (2016). |

| 3 | For more information regarding the PRA buffer calculation and guidance please see PRA’s Statement of Policy, section II: Pillar 2B (PRA 2020e, p. 25). |

| 4 | The stress impact that comprises the first of the three assessments of the PRA buffer refers “an assessment of the amount of capital firms should maintain to withstand a severe stress scenario” as in paragraph 9.3 of PRA’s Statement of Policy (PRA 2022). |

| 5 | The term ‘pragmatic’ SREP was first used by the European Central Bank and the European Banking Authority (EBA 2020; ECB 2020a, 2020b), with adjustments made based on COVID-19 developments in early 2020. In this context the ‘pragmatic’ SREP refers to understanding the risk management capabilities of the fintech, building on the key components of the SREP but managing expectations, in comparison with systemic and/or more mature institutions. |

| 6 | Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms and amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 (OJ L 321, 26.6.2013) - CRR, Regulation (EU) 2019/876 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2019 amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as regards the leverage ratio, the net stable funding ratio, requirements for own funds and eligible liabilities, counterparty credit risk, market risk, exposures to central counterparties, exposures to collective investment undertakings (CIU), large exposures, reporting and disclosure requirements, and Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 – CRR II. |

| 7 | Directive 2013/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms, amending Directive 2002/87/EC and repealing Directives 2006/48/EC and 2006/49/EC (OJ L 176, 27.6.2013)—CRD, Directive (EU) 2019/878 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2019 amending Directive 2013/36/EU as regards exempted entities, financial holding companies, mixed financial holding companies, remuneration, supervisory measures and powers and capital conservation measures—CRD V. |

| 8 | The recommendations denoted in bold and underlined refer to amendments of the actual PRA’s ICAAP guidance SS31/15 (PRA 2021c). |

| 9 | For further guidance on the SWD (not fintech/FGF specific) please see the Single Resolution Board guidance (SRB 2021) and BoE’s CP9/17 (PRA 2017). CP9/17 captures the regulatory expectations in relation to SWD with respect to recovery options and the firms’ recovery plans (PRA 2017), with more information captured in the SS19/13 (PRA 2018). |

| 10 | For more information about regulatory sandboxes with country examples please see IMF’s report (2019, p. 21). |

| 11 | Figure 1 has been adapted from BoE’s regulatory expectations New Bank Start-up Unit (NBSU) (BoE 2022), presenting the challenges and key points to address in relation to ICAAP documents and recovery plans. |

| 12 | Figure 2 has been adapted from Arner et al. (2015) depicting the regulatory threshold approaches vs. growth models for fintech and the journey of a bank from pre-authorisation to established bank from the PRA as in fig.1 SS3/21, PRA (2021a, 2021b). |

| 13 | Based on the PRA’s guidance (PRA 2020a), new banks refer to ‘firms that are in the ‘mobilisation stage’ (authorisation with restrictions) and those that have received authorisation without restrictions within the past 12 months, whereas growing banks refer to banks that are typically between 1 and 5 years post-authorisation without restrictions’. |

| 14 | Referring to data privacy, security, discontinuity of banking services, inappropriate marketing practices based on the Basel Committee of Banking Supervision (BCBS 2018, graph 6). |

| 15 | These are strategic and profitability risks, cyber-risk, high operational risk-systemic/idiosyncratic dimensions, third-party/verndom management risk linked to outsourcing, increased interconnectedness between financial parties, compliance risk inclusive of failure to protect consumers and data protection regulation, money laundering, liquidity risk and volatility of bank funding sources based on the (BCBS 2018, graph 6). |

| 16 | The definition of this risk denoted as ICT refers to the ‘risks of losses or potential loess related to the use of network information systems or communication technology, including breach of confidentiality, failure of systems, unavailability or lack of integrity of data and systems, and cyber risk’ (EC 2021a, 47 Article 1 20k 52). |

| 17 | Please see figure 4 for micro-financial risks and figure 5 for the macro-financial risks from FSB (2017). |

| 18 | For further detial please see the published Pillar 3 disclosures and reports from ClearBank, Atom Bank, Monzo Bank and Starling Bank. |

| 19 | Note that these fintech are challenger banks as described in Hodson (2021). |

| 20 | For further information please see the study of Borio et al. (2022) that presents a comparison between AB regulation versus entity-based (EB) regulation under the aim of maintaining financial stability. |

| 21 | For the evolution of financial services with technological innovations and fintech solutions please see Figure 1 of IMF’s report (2019). |

| 22 | For a list of the key fintech products and services please see BCBS (2018, graph 1). |

| 23 | Note that conduct and fairness, competition and market development (Arner et al. 2015) are not examined in this paper. |

| 24 | Referring to recommendations 7 (‘safeguarding the financial system from evolving risks’), 8 (‘enhancing protection against cyber-risks’) and 9 (‘embracing digital regulation’) as in Van Steenis’ report (2019). |

| 25 | This refers to implementing recommendation 1.3 (p. 33) and 2.4 (p. 37) in particular, with recommendations 1 (p. 21) and 2 mainly (p. 35) (Kalifa 2021). |

| 26 | An example about policy cooperation regarding cyber security and cyber risks is the cyber resilience coordination centre (CRCC) (Doerr et al. 2022). |

References

- Aaron, Meyer, Francisco Rivadeneyra, and Samantha Sohal. 2017. Fintech: Is This Time Different? A Framework for Assessing Risks and Opportunities for Central Banks. Bank of Canada Staff Discussion Paper 2017–10, July 2017. Ottawa: Bank of Canada. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, Ioannis. 2018. Fintech and regtech: Impact on regulators and banks. Journal of Economics and Business 100: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, Douglas, Jannos Barberis, and Ross Buckley. 2015. The Evolution of Fintech: A New Post-Crisis Paradigm? University of Hong Kong Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 2015/047, UNSW Law Research Paper No. 2016–62. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atom Bank Plc Annual Report 2021/2022. 2022a. Available online: https://www.atombank.co.uk/~/docs/annual-report-21-22.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Atom Bank Plc Pillar 3 Report 2021/2022. 2022b. Available online: https://www.atombank.co.uk/~/docs/pillar-3-disclosures-21-22.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Barefoot, Jo Ann. 2020. Digitizing Financial Regulation: Regtech as a Solution for Regulatory Inefficiency and Ineffectiveness. M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series No. 150. Cambridge: Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government Weil Hall, Harvard Kennedy School. Available online: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/mrcbg/files/AWP_150_final.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- BCBS. 2011. Basel III: A Global Regulatory Framework for More Resilience Banks and Banking Systems. December 2020 (rev June 2011). Basel: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Bank for International Settlements. [Google Scholar]

- BCBS. 2017. Basel III: Finalising Post-Crisis Reforms. Basel: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Bank for International Settlements, December. [Google Scholar]

- BCBS. 2018. Implications of Fintech Developments for Banks and Bank Supervisors. Sound Practices, February 2018. Basel: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. [Google Scholar]

- Beaman, Melanie. 2019. Review and Findings: Fast Growing Firms. Dear CEO Letter, 12 June 2019. London: Prudential Regulation Authority, Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- Beau, Dennis. 2022. Between Mounting Risks and Financial Innovation—The Fintech Ecosystem at a Crossroads. Speech by Mr Denis Beau, First Deputy Governor of the Bank of France, at the FinTech R: Evolution 2022, organised by France FinTech, Paris, 20 October 2022. Paris: Banque de France. [Google Scholar]

- Binham, Caroline, and Nicholas Megaw. 2019. Bank of England Finds UK Challenger Banks Cut Corners. Financial Times, June 14. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Julia. 2010. Financial Markets. In The Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research. Edited by Peter Cane and Herbert Kritzer. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BoE. 2014. A Review of Requirements for Firms Entering into or Expanding in the Banking Sector: One Year on 7 July 2014. London: Financial Conduct Authority and Prudential Regulation Authority, Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- BoE. 2016. New Bank Start-Up Unit Launched by the Financial Regulators. 20 January, Bank of England News Release. Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/news/2016/january/new-bank-startup-unit-launched-by-the-financial-regulators.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- BoE. 2018. Stress Testing the UK Banking System: Key Elements of the 2018 Stress Test. London: Bank of England, March. [Google Scholar]

- BoE. 2019. New Economy, New Finance, New Bank. The Bank of England’s Response to the van Steenis Review on the Future of Finance. London: Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- BoE. 2022. Regulatory Expectations. 9 February 2022, Prudential Regulation, New Bank Start-up Unit, Bank of England. Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/new-bank-start-up-unit/regulatory-expectations (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Borio, Claudio, Stijn Claessens, and Nikola Tarashev. 2022. Entity-Based vs. Activity-Based Regulation: A Framework and Applications to Traditional Financial Firms and Big Techs. Bank for International Settlements, Financial Stability Institute, Occasional Paper No 19. Basel: Bank for International Settlements, Financial Stability Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Eric, and Dóra Piroska. 2022. Governing Fintech and Fintech as Governance: The Regulatory Sandbox, Riskwashing, and Disruptive Social Classification. New Political Economy 27: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, Mark. 2017. The Promise of FinTech—Something New Under the Sun? In Speech Given by Mark Carney Governor of the Bank of England Chair of the Financial Stability Board Deutsche Bundesbank G20 Conference on “Digitising Finance, Financial Inclusion and Financial Literacy. Wiesbaden 25 January 2017. London: Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- Carstens, Agustín. 2021. Public Policy toward Big Techs in Finance. Speech at the Asia School of Business Conversations on Central Banking webinar “Finance as information”, 27 January. Basel: Bank for International Settlements. Available online: https://www.bis.org/speeches/sp210121.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Carstens, Agustín, Stijn Claessens, Fernando Restoy, and Hyun Song Shin. 2021. Regulating Big Techs in Finance. Basel: Bank for International Settlements. [Google Scholar]

- ClearBank Pillar 3 Disclosure 2019. 2020. Available online: https://clear.bank/uploads/assets/ClearBank-Pillar-3-disclosure-2019.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- ClearBank Pillar 3 Disclosure 2020. 2021. Available online: https://clear.bank/uploads/assets/Clear.Bank-Pillar-3-disclosure-2020.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- ClearBank Annual Report and Accounts 2021. 2022a. Available online: https://clear.bank/uploads/assets/ClearBank-Annual-Report-2021.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- ClearBank Pillar 3 Disclosure 2021. 2022b. Available online: https://clear.bank/uploads/assets/ClearBank-Pillar-3-disclosure-2021.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Crisanto, Juan Carlos, Johannes Ehrentraud, and Marcos Fabian. 2021. Big Techs in Finance: Regulatory Approaches and Policy Options. FSI Briefs No 12 March 2021. Basel: Financial Stability Institute, Bank for International Settlements. [Google Scholar]

- de la Mano, Miguel, and Jorge Padilla. 2018. Big Tech Banking. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3294723 (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Dent, Kieran, Ben Westwood, and Miguel Segoviano. 2016. Stress Testing of Banks: An Introduction. Bank of England, Quarterly Bulletin 2016 Q3. London: Bank of England, Quarterly Bulletin, pp. 130–43. [Google Scholar]

- Doerr, Sebastian, Leonardo Gambacorta, Thomas Leach, Bertrand Legros, and David Whyte. 2022. Cyber Risk in Central Banking. BIS Working Papers No 1039. Basel: Monetary and Economic Department, Bank for International Settlements. [Google Scholar]

- EBA. 2014. Guidelines on Common Procedures and Methodologies for the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP). EBA/GL/2014/13, 19 December 2014. London: European Banking Authority. [Google Scholar]

- EBA. 2020. Final Report on the Pragmatic 2020 SREP. EBA/GL/2020/10, 23 July 2020. Paris: European Banking Authority. [Google Scholar]

- EBA. 2022. Final Report: Guidelines on Common Procedures and Methodologies for the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) and Supervisory stress Testing under Directive 2013/36/EU. EBA/GL/2022/03, 18 March 2022. Paris: European Banking Authority. [Google Scholar]

- EC. 2021a. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as Regards Requirements for Credit Risk, Credit Valuation Adjustment Risk, Operational Risk, Market Risk and the Output Floor. Brussels, 27.10.2021, COM(2021) 664 final, 2021/0342 (COD). Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- EC. 2021b. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Directive 2013/36/EU as Regards Supervisory Powers, Sanctions, Third-Country Branches, and Environmental, Social and Governance Risks, and Amending Directive 2014/59/EU. Brussels, 27.10.2021, COM(2021) 663 Final, 2021/0341 (COD). Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- ECB. 2020a. A pragmatic SREP Delivers Appropriate Supervision for the Crisis. Blog Post by Elizabeth McCaul, Member of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, 12 May 2020, European Central Bank. Available online: https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/press/blog/2020/html/ssm.blog200512~0958bc57fc.en.html (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- ECB. 2020b. Taking a Pragmatic Approach to SREP. Supervision Newsletter, 13 May 2020, European Central Bank. Available online: https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/press/publications/newsletter/2020/html/ssm.nl200513_2.en.html (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- ECB. 2022. The Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process. European Central Bank. Available online: https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/banking/srep/html/index.en.html (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Ehrentraud, Johannes, Jamie Lloyd Evans, Amélie Monteil, and Fernando Restoy. 2022. Big Tech Regulation: In Search of a New Framework. FSI Occasional Paper, No 20. Basel: Financial Stability Institute, Bank for International Settlements. [Google Scholar]

- Enria, Andrea. 2018. Designing a Regulatory and Supervisory Roadmap for FinTech. Speech by Andrea Enria, Chairperson of the European Banking Authority (EBA) at Copenhagen Business School 09 March 2018. Paris: European Banking Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Fáykiss, Péter, Dániel Papp, P. Péter Sajtos, and Ágnes Tőrös. 2018. Regulatory Tools to Encourage FinTech Innovations: The Innovation Hub and Regulatory Sandbox in International Practice. Financial and Economic Review 17: 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FCA. 2015. Regulatory sandbox. Financial Conduct Authority. Available online: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/research/regulatory-sandbox.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- FPC. 2021. Financial Policy Summary and Record of the Financial Policy Committee Meeting on 11 March 2021. London: Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- FSB. 2017. Financial Stability Implications from FinTech: Supervisory and Regulatory Issues That Merit Authorities’ Attention. Basel: Financial Stability Board, June 27. [Google Scholar]

- FSB. 2019. Decentralised Financial Technologies. Report on Financial Stability, Regulatory and Governance Implications. 6 June 2019. Basel: Financial Stability Board. [Google Scholar]

- FSB. 2022. FinTech and Market Structure in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Financial Stability. Basel: Financial Stability Board, March 21. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, Johannes, and Daniel Rugilo. 2019. The Predicament of Fintechs in the Environment of Traditional Banking Sector Regulation—An Analysis of Regulatory Sandboxes as a Possible Solution. Credit and Capital Markets 52: 323–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandri, Elisabetta. 2012. Basel III, Pillar 2: The Role of Banks’ Internal Control Systems. In Crisis, Risk and Stability in Financial Markets. Edited by Juan Fernández de Guevara Radoselovic and José Pastor Monsálvez. London: Palgrave Macmillan Studies in Banking and Financial Institutions, Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, Dermot. 2021. The politics of FinTech: Technology, regulation, and disruption in UK and German retail banking. Public Administration 99: 859–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRS 9 Financial Instruments. International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). 2022. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ifrs-9-financial-instruments/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- IMF. 2018. The Bali Fintech Agenda. IMF policy paper. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. 2019. Fintech: The Experience So Far. IMF Policy Paper No. 2019/024. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Kalifa, Ron. 2021. Kalifa Review of UK Fintech. Independent report on the UK Fintech sector by Ron Kalifa OBE, Policy Paper. London: HM Treasury. [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson, William. 2017. Regulating Fintech. Vanderbilt Law Review 71: 1167–226. [Google Scholar]

- Mnohoghitnei, Irinia, Simon Scorer, Kushali Shingala, and Oliver Thew. 2019. Embracing the Promise of Fintech. Topical Article, Quarterly Bulletin, 2019 Q1 1–13. London: Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- Monzo Bank. 2020. Annual Report and Group Financial Statements. Available online: https://monzo.com/investor-information/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Monzo Bank. 2021a. Annual Report and Group Financial Statements. Available online: https://monzo.com/docs/monzo-annual-report-2021.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Monzo Bank. 2021b. Pillar 3 Disclosures. Available online: https://monzo.com/docs/monzo-pillar-3-2021.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Monzo Bank. 2022. Pillar 3 Disclosures. Available online: https://monzo.com/docs/monzo-pillar-3-2022.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- New Bank Start-Up Unit. Bank of England. 2022. Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/new-bank-start-up-unit (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Partington, Martin. 2010. Empirical Legal Research and Policy-making. In The Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research. Edited by Peter Cane and Herbert Kritzer. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- PRA. 2017. Recovery Planning. Consultation Paper CP9/17, June 2017. London: Prudential Regulation Authority, Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- PRA. 2018. Resolution Planning. Supervisory Statement SS19/13, June 2018 (Updating January 2015). London: Prudential Regulation Authority, Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- PRA. 2020a. Non-Systemic UK Banks: The Prudential Regulation Authority’s Approach to New and Growing Banks. Consultation Paper CP9/20, July 2020. London: Prudential Regulation Authority, Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- PRA. 2020b. Recovery Planning. Supervisory Statement SS9/17, December 2020 (Updating July 2020). London: Prudential Regulation Authority, Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- PRA. 2020c. Capital Requirements Directive V (CRD V). Consultation Paper, CP 12/20 (July 2020). London: Prudential Regulation Authority, Bank of England. [Google Scholar]