Discretionary Extensions to Unemployment Insurance Compensation and Some Potential Costs for a McCall Worker

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Two Episodes of Extended Benefits

2.1. Extensions Created in Response to the Great Recession

2.2. Extensions Created in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

3. Job Search with Expiring Benefits

3.1. The Sequential Search Environment with Expiring Benefits

3.2. Optimal Search

4. Extending Benefits by Discretion

- Whether benefits are extended;

- The length of the extension.

4.1. Environment

4.2. Optimal Search

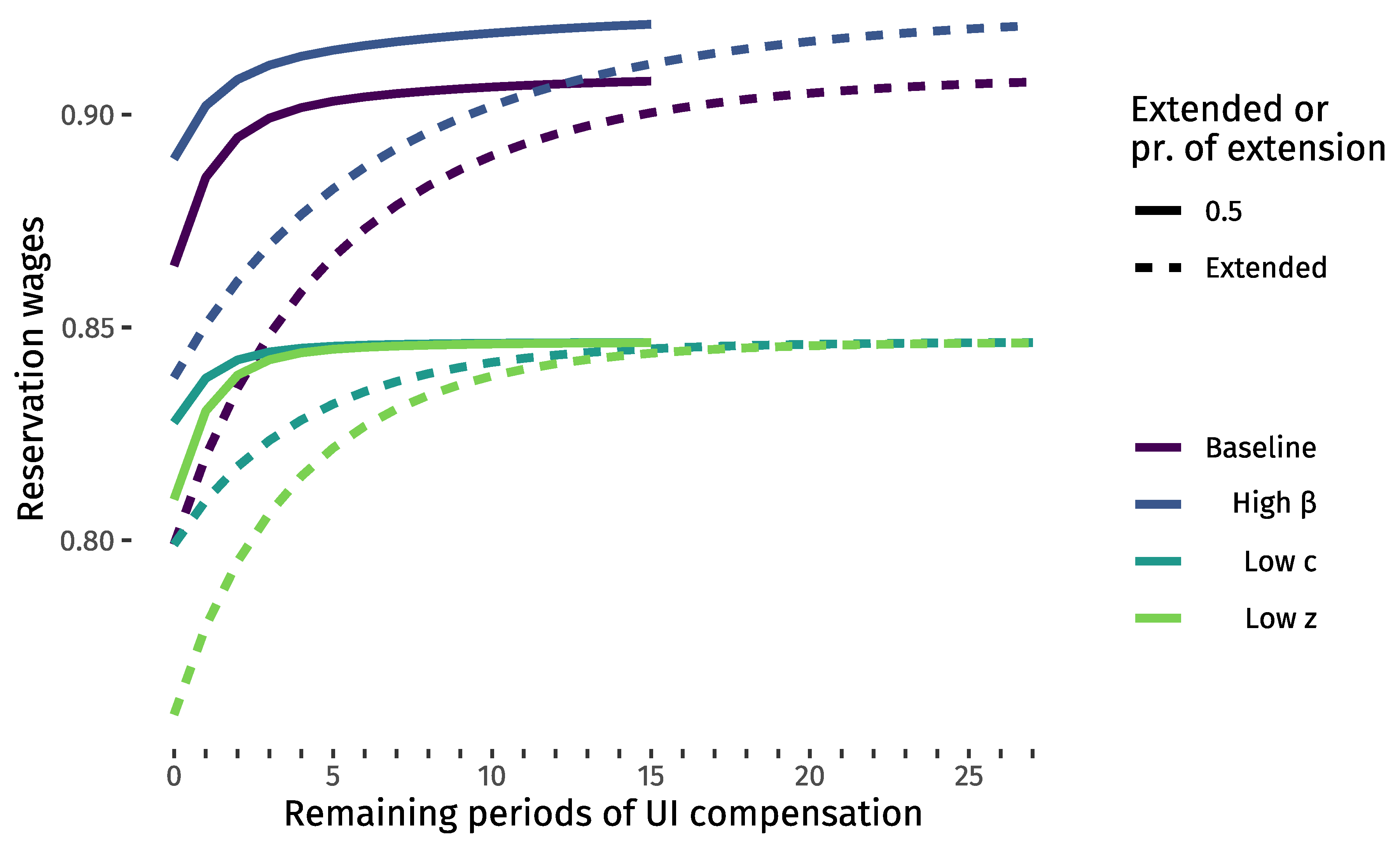

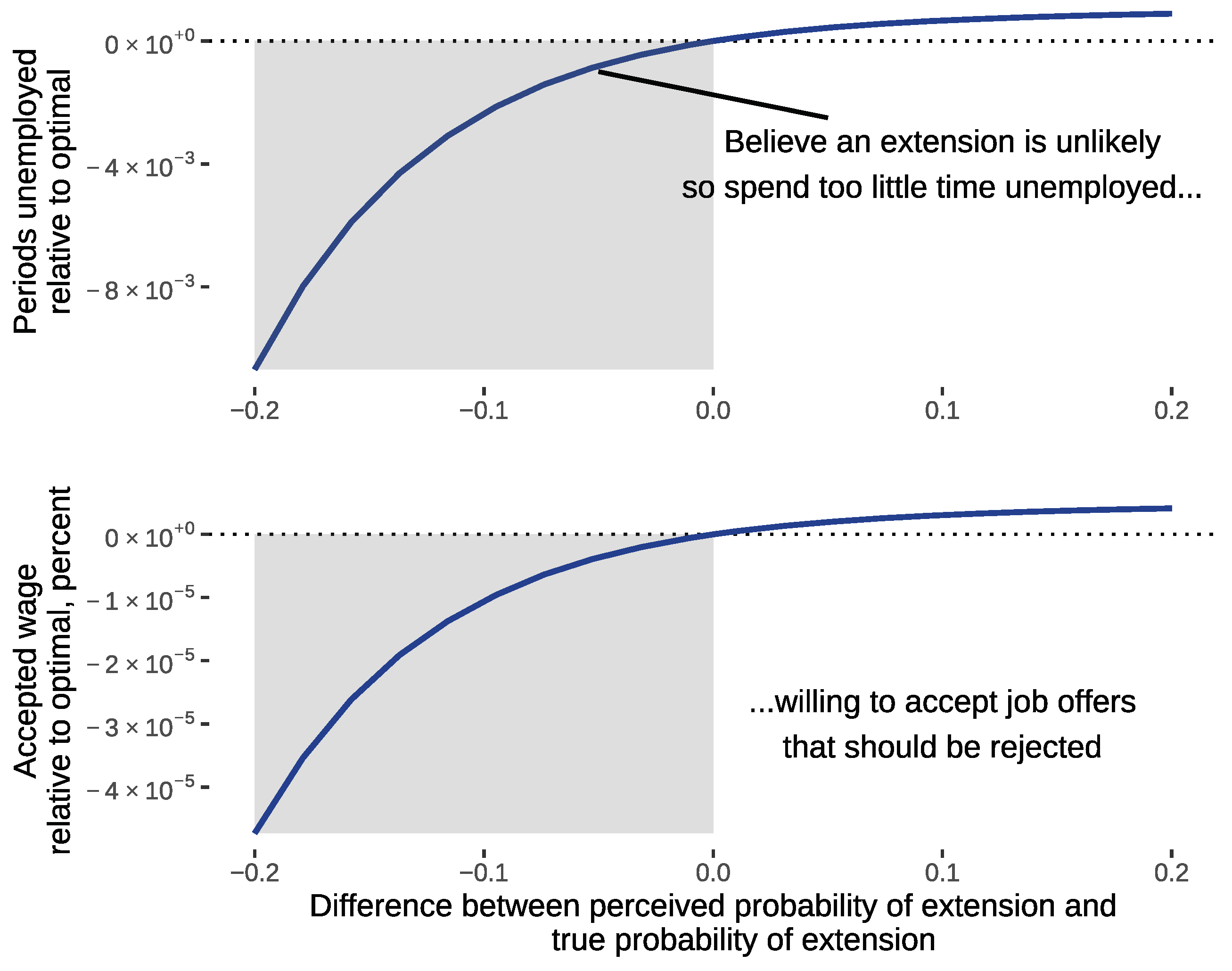

4.3. How Beliefs Affect Optimal Search

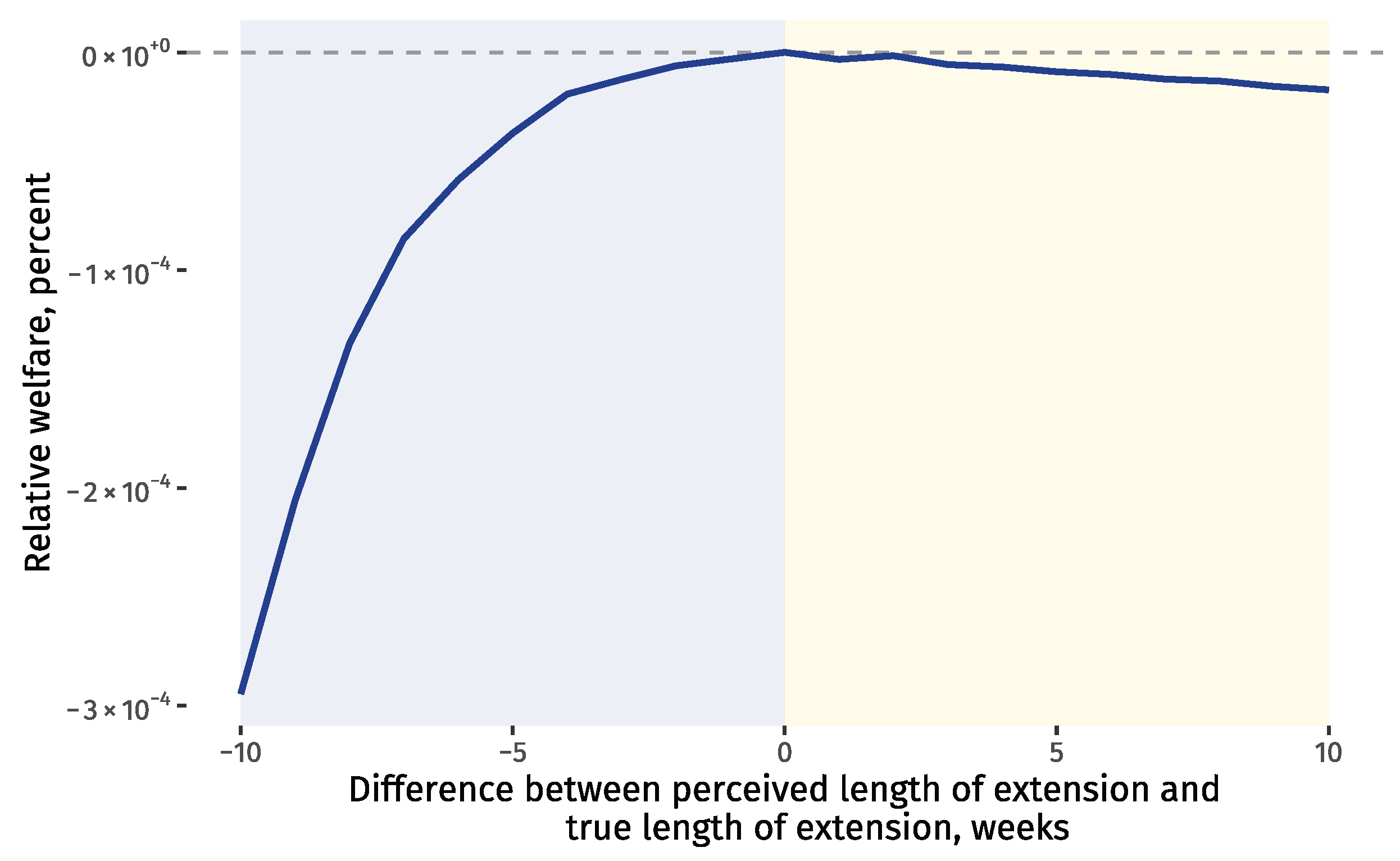

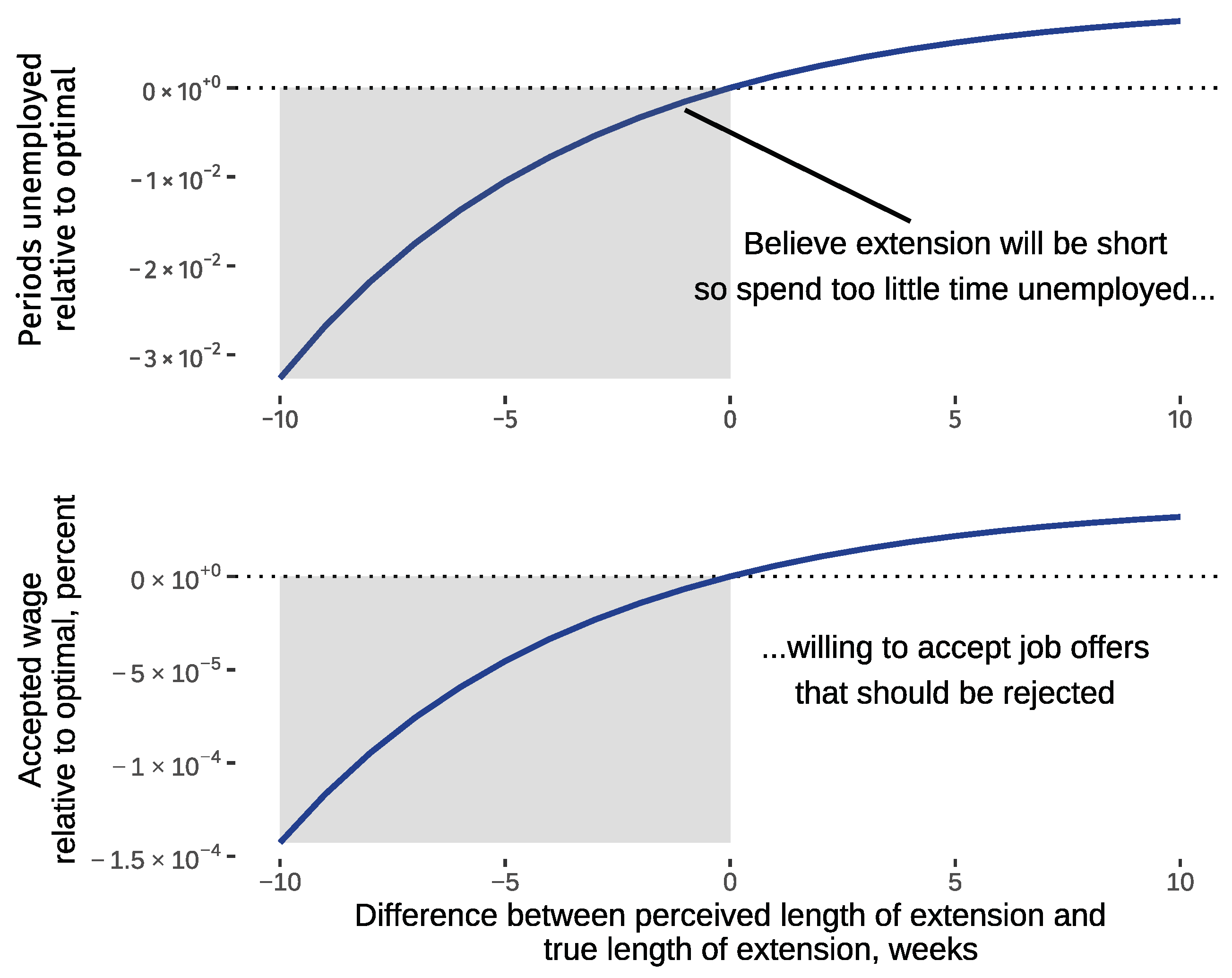

5. Welfare

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CARES Act | Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act |

| EB | Extended Benefits |

| EUC | Emergency Unemployment Compensation |

| FPUC | Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation |

| PEUC | Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation |

| PUA | Pandemic Unemployment Assistance |

| UI | Unemployment insurance |

Appendix A. Some Additional Background on the UI System

Appendix B. Canonical Job Search with Finite UI Benefits

Appendix C. Proof of Proposition 1 in the Main Text

Appendix C.1. Proof of Lemmas A1 and A2

Appendix C.2. Details of the Proof of Proposition 1 in the Main Text

- The existence of reservation wages is established, which justifies writing the problem in terms of reservation wages;

- The existence and uniqueness of is established. This is performed by an appeal to the contraction mapping theorem;

- The sequence of reservation wages, , are then computed, starting from . It is established that the worker is less selective when there are fewer remaining periods of UI benefits, which is expressed in Equation (7) of Proposition 1;

- The last step establishes that and .

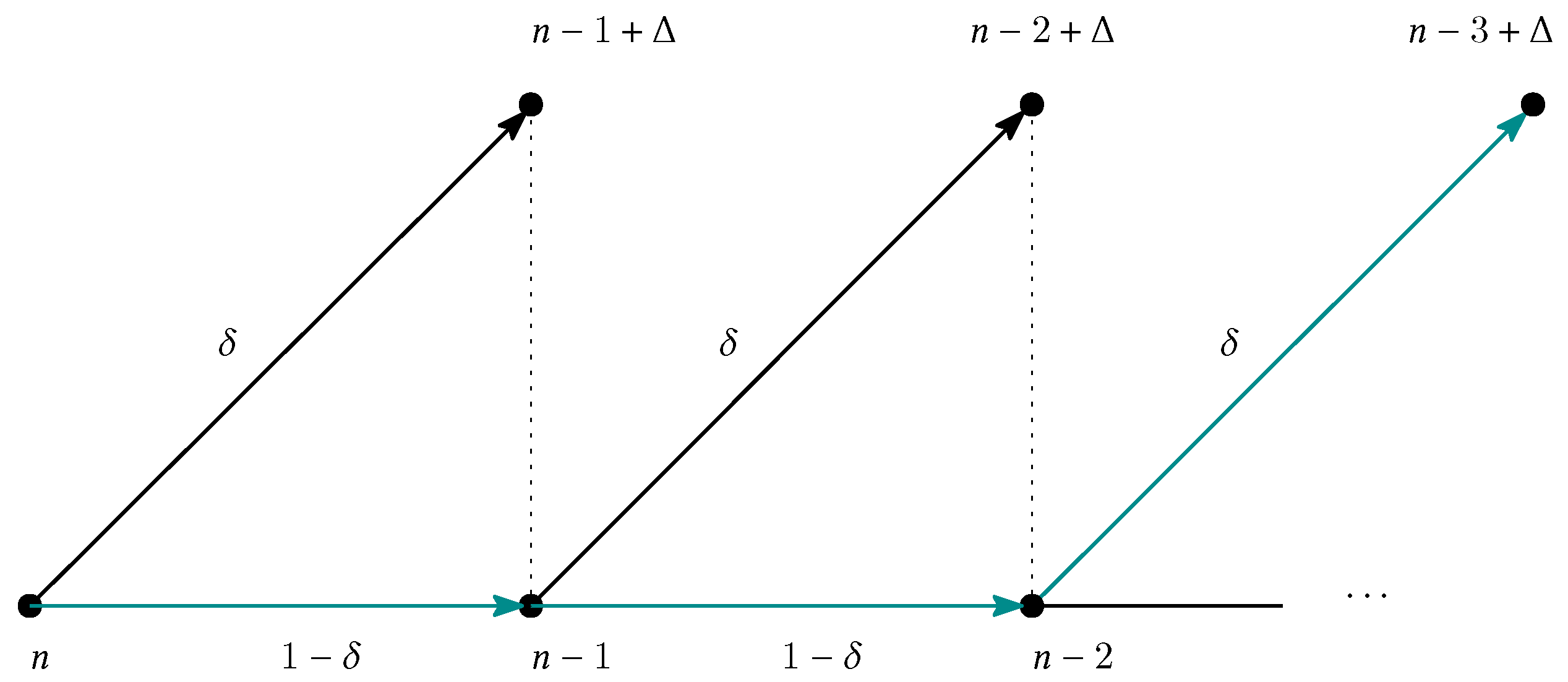

Appendix D. Allowing for Benefits to be Extended by Discretion

Appendix D.1. Description of the Economic Environment

Appendix D.2. Interpreting Search in terms of Reservation Wages

Appendix E. Proof of Proposition 2 in the Main Text

- Lemma A3 establishes the existence and uniqueness of by appealing to the contraction mapping theorem;

- Lemma A4 establishes monotonicity: . Reservation wages increase in the remaining periods of UI compensation benefits;

- Lemma A5 establishes an auxiliary result used in later proofs;

- Lemma A6 establishes that reservation wages fall within the interior of the support of wage offers: .

Appendix E.1. Proof of Lemma A3

Appendix E.2. Proof of Lemma A4

Appendix E.3. Proof of Lemma A5

Appendix E.4. Proof of Lemma A6

Appendix F. Proof of Proposition 3 in the Main Text

- Lemma A7 establishes that is increasing in , holding constant ;

- Lemma A8 establishes that is increasing in , holding constant .

Appendix F.1. Proof of Lemma A7

Appendix F.2. Proof of Lemma A8

Appendix G. How β, c, and z Affect Reservation Wages

Appendix H. Expressions When Wages Offers are Characterized by a Uniform Distribution

Appendix H.1. Basic Job Search with Finite UI Benefits

Appendix H.2. Allowing for an Extension to Benefits

Appendix H.3. Welfare

| 1 | Triggers for EB weeks may involve thresholds based on (1) a moving average of a state’s unemployment rate, or (2) the insured unemployment rate, which is the ratio of unemployment-compensation claimants divided by individuals in jobs covered by unemployment compensation (so, for example, not the self-employed and gig-economy workers) (Whittaker and Isaacs 2022). Chodorow-Reich and Coglianese (2019, p. 158, Figure 2) show data on the number UI recipients who claim regular, EB, and emergency weeks created by temporary extension. Extended benefits are relied upon less frequently than emergency benefits. |

| 2 | “When a state triggers off of an EB period, all EB benefit payments in the state cease immediately” (Whittaker and Isaacs 2022, p. 7). |

| 3 | The dates for this thought experiment come from data in (Rothstein 2011, p. 150, Table 1) and data available at https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claims_arch.asp, accessed on 27 September 2023. Trigger dates for extended benefits and the EUC program are included in Supplementary Materials. |

| 4 | As of 11 August 2023, the 13 March date is reported on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 timeline. |

| 5 | In addition, workers in 18 states faced a cutoff in compensation-benefit generosity when their states opted out of the FPUC and PUA progams in June 2021, before the programs were set to expire in September 2021, citing labor-supply issues (Holzer et al. 2021). There are many other parts to the UI system that are beyond the scope of this paper. Whittaker and Isaacs (2014, 2022) and Spadafora (2023) provide excellent, detailed coverage of the UI system. Fujita (2010), Rothstein (2011), and Chodorow-Reich and Coglianese (2019) provide excellent discussion of the many temporary programs. |

| 6 | In Krueger and Mueller’s (2016) survey on reservation wages, which I discuss below, over half of respondents with less than 3 months of unemployment duration report have no savings. |

| 7 | Ljungqvist and Sargent (2018) provide an informative textbook exposition. Rogerson et al. (2005) show how a similar decision-making environment fits into larger models of the macroeconomy that feature search. |

| 8 | Appendix C considers the case where the support of wages is . In that case, I establish that contracts through direct verification, which requires more algebra. |

| 9 | Expression (11) is a generalization of Equation (6.3.3) in (Ljungqvist and Sargent 2018, p. 163). More details are provided in Appendix D. |

| 10 | Appendix E also shows that the support of wages can be extended to . |

| 11 | This assumption offers the opportunity to compare numerical work with closed-form expressions. Replication files for the paper compare reservation wages computed using closed-form expressions with those computed using Monte Carlo integration. Closed-form expressions are shared in Appendix H. |

| 12 | The simulations suggest that welfare is relatively flat, requiring a large number of runs. |

| 13 | Less is known about how psychology influences the job search. Two examples are provided by DellaVigna and Paserman (2005) and Paserman (2008), who study how impatience affects searching. |

| 14 | In related work, Shimer and Werning (2008) establish that optimal UI compensation involves constant or nearly constant benefits and, thus, a single reservation wage. Both papers informatively consider cases where workers save. |

| 15 | |

| 16 |

References

- Acemoglu, Daron. 2001. Good jobs versus bad jobs. Journal of Labor Economics 19: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, Daron. 2009. Introduction to Modern Economic Growth. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Akerlof, George A., and Janet L. Yellen. 1990. The fair wage-effort hypothesis and unemployment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 105: 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, Sarah, Olivia Lofton, Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau, and Robert G. Valletta. 2022. Unemployment Insurance Withdrawal. FRBSF Economic Letter. 2022-09. Available online: https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2022/april/unemployment-insurance-withdrawal/ (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Anquandah, Jason S., and Leonid V. Bogachev. 2019. Optimal stopping and utility in a simple model of unemployment insurance. Risks 7: 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, David H., and Mark G. Duggan. 2003. The rise in the disability rolls and the decline in unemployment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 157–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbanchon, Thomas Le, Roland Rathelot, and Alexandra Roulet. 2019. Unemployment insurance and reservation wages: Evidence from administrative data. Journal of Public Economics 171: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, Truman F. 1999. Why Wages Don’t Fall During a Recession. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boar, Corina, and Simon Mongey. 2020. Dynamic Trade-Offs and Labor Supply under the Cares Act. Working Paper 27727. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, Christopher, Arindrajit Dube, Lucas Goodman, and Ethan Kaplan. 2021. Unemployment insurance generosity and aggregate employment. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13: 58–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, Victor. 1985. Metric Spaces. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdett, Kenneth. 1979. Unemployment insurance payments as a search subsidy: A theoretical analysis. Economic Inquiry 17: 333–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdett, Kenneth, and Tara Vishwanath. 1988. Declining reservation wages and learning. The Review of Economic Studies 55: 655–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplin, Andrew, and John V. Leahy. 2019. Wishful Thinking. Working Paper 25707. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, David, and Phillip B. Levine. 2000. Extended benefits and the duration of UI spells: Evidence from the New Jersey extended benefit program. Journal of Public Economics 78: 107–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, David, Andrew Johnston, Pauline Leung, Alexandre Mas, and Zhuan Pei. 2015. The effect of unemployment benefits on the duration of unemployment insurance receipt: New evidence from a regression kink design in missouri, 2003–2013. American Economic Review 105: 126–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, David, Raj Chetty, and Andrea Weber. 2007. The spike at benefit exhaustion: Leaving the unemployment system or starting a new job? American Economic Review 97: 113–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, Raj. 2006. A general formula for the optimal level of social insurance. Journal of Public Economics 90: 1879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, Raj. 2008. Moral hazard versus liquidity and optimal unemployment insurance. Journal of Political Economy 116: 173–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, Raj. 2009. Sufficient statistics for welfare analysis: A bridge between structural and reduced-form methods. Annual Review of Economics 1: 451–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, Raj, and Amy Finkelstein. 2013. Social insurance: Connecting theory to data. In Handbook of Public Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 5, pp. 111–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel, and John Coglianese. 2019. Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilizethe American Economy. Chapter Unemployment Insurance and Macroeconomic Stabilization, The Hamilton Project and The Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, pp. 153–180. [Google Scholar]

- Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel, and Loukas Karabarbounis. 2016. The cyclicality of the opportunity cost of employment. Journal of Political Economy 124: 1563–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel, John Coglianese, and Loukas Karabarbounis. 2019. The macro effects of unemployment benefit extensions: A measurement error approach. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134: 227–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaVigna, Stefano, and M. Daniele Paserman. 2005. Job search and impatience. Journal of Labor Economics 23: 527–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterle, Steven, Otávio Bartalotti, and Quentin Brummet. 2020. Revisiting the effects of unemployment insurance extensions on unemployment: A measurement-error-corrected regression discontinuity approach. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12: 84–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faberman, R. Jason, Andreas Mueller, and Ayşegül Şahin. 2022. Has the Willingness to Work Fallen during the Covid Pandemic? Labour Economics 79: 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, Henry S., and Robert G. Valletta. 2015. Do extended unemployment benefits lengthen unemployment spells?: Evidence from recent cycles in the u.s. labor market. Journal of Human Resources 50: 873–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, Henry S., Jesse Rothstein, and Robert G. Valletta. 2015. The effect of extended unemployment insurance benefits: Evidence from the 2012–2013 phase-out. American Economic Review 105: 171–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Shigeru. 2010. Economic Effects of the Unemployment Insurance Benefit. Business Review Q4. Available online: https://www.philadelphiafed.org/the-economy/macroeconomics/economic-effects-of-the-unemployment-insurance-benefit (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Hagedorn, Marcus, Fatih Karahan, and Iourii Manovskii Kurt Mitman. 2019. Unemployment Benefits and Unemploymentin the Great Recession: The Role of Equilibrium Effects. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report No. 646. Available online: https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr646 (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Hagedorn, Marcus, Iourii Manovskii, and Kurt Mitman. 2016. Interpreting Recent Quasi-Experimental Evidence on the Effects of Unemployment Benefit Extensions. Technical Report. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendren, Nathaniel. 2017. Knowledge of future job loss and implications for unemployment insurance. American Economic Review 107: 1778–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, Harry J., R. Glenn Hubbard, and Michael R. Strain. 2021. Did Pandemic Unemployment Benefits Reduce Employment? Evidence from Early State-Level Expirations in June 2021. Working Paper 29575. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, Simon, Benjamin Schoefer, Samuel Young, and Josef Zweimüller. 2020. Wages and the value of nonemployment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135: 1905–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Andrew C., and Alexandre Mas. 2018. Potential unemployment insurance duration and labor supply: The individual and market-level response to a benefit cut. Journal of Political Economy 126: 2480–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, Lisa B. 2011. Unemployment insurance and job search in the great recession: Comments and discussion. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 42: 205–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kekre, Rohan. 2023. Unemployment insurance in macroeconomic stabilization. Review of Economic Studies 90: 2439–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemka, Gaurav, Steven Roberts, and Timothy Higgins. 2017. The impact of changes to the unemployment rate on australian disability income insurance claim incidence. Risks 5: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroft, Kory, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo. 2016. Should unemployment insurance vary with the unemployment rate? theory and evidence. The Review of Economic Studies 83: 1092–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, Alan B., and Andreas I. Mueller. 2016. A contribution to the empirics of reservation wages. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 8: 142–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, Alan B., and Bruce D. Meyer. 2002. Labor supply effects of social insurance. In Handbook of Public Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier, chp. 33. pp. 2327–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalive, Rafael. 2007. Unemployment benefits, unemployment duration, and post-unemployment jobs: A regression discontinuity approach. American Economic Review 97: 108–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalive, Rafael, and Josef Zweimüller. 2004. Benefit entitlement and unemployment duration. Journal of Public Economics 88: 2587–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landais, Camille, and Johannes Spinnewijn. 2021. The value of unemployment insurance. The Review of Economic Studies 88: 3041–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landais, Camille, Pascal Michaillat, and Emmanuel Saez. 2018. A macroeconomic approach to optimal unemployment insurance: Theory. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10: 152–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungqvist, Lars, and Thomas J. Sargent. 2017. The fundamental surplus. American Economic Review 107: 2630–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungqvist, Lars, and Thomas J. Sargent. 2018. Recursive Macroeconomic Theory, 4th ed. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marinescu, Ioana. 2017. The general equilibrium impacts of unemployment insurance: Evidence from a large online job board. Journal of Public Economics 150: 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, Ioana, and Daphné Skandalis. 2021. Unemployment insurance and job search behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136: 887–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, Ioana, Daphné Skandalis, and Daniel Zhao. 2021. The impact of the federal pandemic unemployment compensation on job search and vacancy creation. Journal of Public Economics 200: 104471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, J. J. 1970. Economics of information and job search. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 84: 113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitman, Kurt, and Stanislav Rabinovich. 2015. Optimal unemployment insurance in an equilibrium business-cycle model. Journal of Monetary Economics 71: 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, Dale T. 1977. Unemployment insurance and job search decisions. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 30: 505–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekoei, Arash, and Andrea Weber. 2017. Does extending unemployment benefits improve job quality? American Economic Review 107: 527–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paserman, M. Daniele. 2008. Job search and hyperbolic discounting: Structural estimation and policy evaluation. The Economic Journal 118: 1418–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosky-Nadeau, Nicolas. 2020. Reservation benefits: Assessing job acceptance impacts of increased UI payments. In Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper Series. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosky-Nadeau, Nicolas, and Robert G. Valletta. 2021. UI generosity and job acceptance: Effects of the 2020 CARES act. In Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper Series. San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper 2021-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, Richard, Robert Shimer, and Randall Wright. 2005. Search-theoretic models of the labor market: A survey. Journal of Economic Literature 43: 959–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Sheldon. 1983. Introduction to Stochastic Dynamic Programming. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, Jesse. 2011. Unemployment insurance and job search in the great recession. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 42: 143–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, Matthew S. 2011. The Impact of Unemployment Insurance Extensions on Disability Insurance Application and Allowance Rates. Boston College Center for Retirement Research Working Paper No. 2011-17. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1956008 (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Schmieder, Johannes F., and Till von Wachter. 2016. The effects of unemployment insurance benefits: New evidence and interpretation. Annual Review of Economics 8: 547–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimer, Robert, and Iván Werning. 2007. Reservation wages and unemployment insurance. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 1145–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimer, Robert, and Iván Werning. 2008. Liquidity and insurance for the unemployed. American Economic Review 98: 1922–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, Gary. 1979. Labor supply effects of extended unemployment benefits. The Journal of Human Resources 14: 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadafora, Francesco. 2023. U.S. unemployment insurance through the covid-19 crisis. Journal of Government and Economics 9: 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, Julie M., and Katelin P. Isaacs. 2014. Extending Unemployment Compensation Benefits during Recessions. Technical Report, Congressional Research Service Report RL34340. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, Julie M., and Katelin P. Isaacs. 2022. Unemployment Insurance (UI) Benefits: Permanent-Law Programs and the COVID-19 Pandemic Response. Technical Report, Congressional Research Service Report R46687. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- Yellen, Janet L. 1984. Efficiency wage models of unemployment. The American Economic Review 74: 200–5. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryan, R. Discretionary Extensions to Unemployment Insurance Compensation and Some Potential Costs for a McCall Worker. Risks 2023, 11, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11100171

Ryan R. Discretionary Extensions to Unemployment Insurance Compensation and Some Potential Costs for a McCall Worker. Risks. 2023; 11(10):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11100171

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyan, Rich. 2023. "Discretionary Extensions to Unemployment Insurance Compensation and Some Potential Costs for a McCall Worker" Risks 11, no. 10: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11100171

APA StyleRyan, R. (2023). Discretionary Extensions to Unemployment Insurance Compensation and Some Potential Costs for a McCall Worker. Risks, 11(10), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11100171