Abstract

Failure to holistically manage risk in Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs) is one of the major causes of small businesses failure. To answer the research question as to what supports the adoption of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) in SMEs, this research aims to analyse Risk Management (RM) in SMEs and develops a framework to facilitate the adoption of ERM. In achieving the primary objective, the research establishes for SMEs: the sources of information for RM; the importance of information governance in managing risk; the fundamentals of RM; and the pillars of RM. Previous research conducted on RM in SMEs reviewed the challenges of the successful implementation of ERM in SMEs and proposed different ways to address these challenges. The common ground reached by the research is that there is a need for the simplification of ERM in SMEs. We followed an interpretive philosophy with an inductive research approach and employed a qualitative methodological choice with a cross-sectional time horizon through data collection, employing a review of the scholarly literature, to, in the end, develop a conceptual Small Medium Enterprises Risk Management Framework (SMERMF). The limitation of the research is that the empirical part of the research has not been concluded yet. To present the results, that will be compared to the theory and conclude the research.

1. Introduction

The challenge of risk management (RM) implementation in small medium enterprises (SMEs) in developing countries necessitates RM guidelines from different angles affecting enterprise risk management (ERM). As much as credit should be given to research that has been conducted to date to simplify RM in SMEs (; ; ; ; ), extant research has not drawn attention to the governance effect and information aspect of a holistic RM approach in SMEs. The impact of information governance may not be isolated from ERM and might not have received attention from researchers, especially for SMEs.

Failure to manage risk in SMEs might be one of the reasons why SMEs in developing countries experience difficulties to grow and be sustainable. This may be attributed to the limited guidelines on pillars and fundamentals for ERM and the mapping of the aspects driving RM in SMEs. There remains an insufficient development of RM in SMEs despite efforts by policymakers to address the causes of failure such as access to finance, technology, and a regulatory framework for SMEs (). Efficiencies in an enterprise are affected by effective internal controls through providing high-quality information that reduces incorrect behaviour (). According to (), it is not possible for an enterprise to operate effectively and efficiently without information governance.

Since an assessment of information governance principles in ERM and its connection to the pillars and fundamentals of RM have been lacking in research for SMEs, it is important to unpack what constitutes the governance of information in SMEs that leads to ERM. () view the successful implementation of ERM as a pillar of good governance; however, () argue that ERM is still not sufficiently developed for successful use in SMEs. Poor information governance and a lack of guidelines on aspects driving ERM might be a barrier to SMEs and ultimately compromise the sustainability of an enterprise. Given the complexity of information as a concept, the focus of our study is narrowed to accounting information. Information governance, in our context, therefore, reduces to accounting information governance.

Given the dearth of research on accounting information governance and the underlying principles, specifically for developing countries’ SMEs, our research aims to analyse RM in SMEs and develop a framework embodying streamlined governance principles to utilise accounting information. The framework is further specialised to cater for SMEs in developing economies. In the process, business aspects that feed into information governance to address ERM will be formulated. The accounting information will be aggregated, communicated, and distributed to facilitate SME decision making.

2. Literature Review

Researchers have scrutinised how ERM can be successfully implemented in SMEs from different perspectives (; ; ; ; ). The successful implementation of ERM is informed by factors such as an executive risk committee; a dedicated corporate risk group Chief Risk Officer (CRO); an internal audit department; skilled managers to promote and engage employees with ERM; risk appetite statements; risk indicators; and the integration of risk with strategic and business planning (). The successful implementation of ERM’s prerequisite of resources does not make it easy for SMEs to implement.

Among other things, the research conducted on RM and SMEs has either been industry-focused (; ; ; ) or researched the association between ERM and other factors (; ). The research of () and () was conducted on the association of ERM and performance, while () focused on business strategy and performance. () emphasise that there is a need for a customised RM framework for SMEs. As such, there might still be a need for guidelines to customise a Risk Management Framework (RMF) for SMEs over and above testing the shortcoming of the existing frameworks.

The basic objective of ERM is to improve the competences of the enterprise in attaining the highest performance, coordinating proper reporting, and ensuring compliance (). ERM positions RM in such a manner that the strategic and emerging opportunities are considered, and better decision making for strategic and operational affairs is enhanced to increase the value of the shareholders (). However, RM in SMEs is not prioritised (), although it is significant for the strategic management of the entity ().

Information governance is imperative for decision making () and is the mainstay for efficient and effective business operations in today’s political and economic global world (). According to (), the entire lifecycle of information in the enterprise is managed through information governance. The goal of information governance is to ensure accurate, relevant, reliable, and comparable information to enable the enterprise to achieve its goal (). Information governance may not be isolated from the sustainability of the business irrespective of whether it is a large enterprise or medium size business, and it therefore has a significant and direct impact on ERM.

SMEs provide approximately 70% of job opportunities and contribute up to approximately 30% of the national gross domestic product (GDP) in South Africa (). Vietnamese SMEs constitute 97% of the total business and 77% of the total employment and contribute 40 to 60% of the GDP (). As a result, the sustainability of SMEs is negatively influenced by the rough competitive environment, which is subject to economic factors (). Without information governance, the enterprise may be exposed to the risk of missing an opportunity to grow and be competitive, degenerating their investments.

It might be difficult to make the right decision in SMEs without relevant information. Hence, the enterprise culture on how the information is governed might not be ignored in SMEs. () illustrates that the size of an enterprise impacts the culture of the enterprise on awareness. () tap into the limitation of knowledge in SMEs regarding the governance of market information. If the information governance is so critical in organisational positioning and sustainability, understanding what role is played by culture in SMEs concerning information governance might not be ignored. The linkage between information governance and the enterprise might directly affect the way risk is managed in SMEs, as information governance and RM are intertwined.

() engaged SMEs on the implementation of RM approaches in their enterprises. They introduced a simplified framework and a customisable methodology practical ERM dual system. () sketch the evolution of RM in SMEs through the analysis of 61 articles published on the subject until the end of 2016. According to (), the studies analysed show that there is a partial application of ERM in SMEs, and more recent studies are emphasising the need for tools and future models to enhance a holistic approach to the implementation of RM in SMEs.

() assessed the relationship between risk drivers and RM processes in SMEs based on Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM). The drivers of the RM process in SMEs are multidimensional; however, the research is focusing on selected factors. The ISM model of () describes a direct and indirect interlink of key factors for the RM process in Polish SMEs. The factors are analysed based on dependence and drive powers. The dependence and drive powers determine the categorisation of the factors.

() focus on RM responsibilities and the perception of risk in Slovakia and Polish SMEs. The research was conducted in both countries, and the results on the basic characteristics were compared. The results showed that RM responsibilities in Polish and Slovak SMEs reside with managing directors and owners. There might be no guarantee that similar results will be obtained if similar research is conducted in a developing country, as the dynamics of SMEs in developing countries might differ from those of developed countries. Secondly, the empirical studies’ focus is on who is responsible for RM rather than on the content of the RM integrative approach.

SMEs in developed countries are supported by different policies from those of developing countries (). Research and development in developed countries are advanced, which enables SMEs in these countries to have access to knowledge resources (). Factors such as the deficiency of standardised and modern tools in the application of strategic planning, insufficient experience in management and specialised areas, and non-exposure to international business environments make SMEs in developing countries operate differently (). However, global market changes affect SMEs in developing and developed countries equally. SMEs from developing countries are not exempted from internationalisation, models of open innovations, networking, and mass customisation because of the fact that they operate in a different environment compared to SMEs from developed countries ().

() analysed the role of ERM in facilitating the association of the performance of SMEs and their business strategy. The results confirm that there is a relationship between ERM, business strategy, and SMEs’ performance. () analysed the management and consideration of risk where the founder runs the enterprise and understands the integration of RM integration in decision making. The end product was an RM decision-making model; however, the model has not been quantified or statistically validated.

3. Problem Statement

() indicate the risks that can negatively impact business performance and ultimately compromise the sustainability and growth of SMEs. They concluded that there is no systematic risk management strategy in most SMEs. Therefore, the statement of the problem is: the failure to holistically manage risk in small medium enterprises (SMEs) is one of the major causes for small businesses failure.

4. Methodology

A systematic literature review was adopted to examine the existing scholarly articles on RM in SMEs. The benefits of using a systematic literature review are transparency and clear procedures for assessing the field of research relevant to the research topic, and this method has been commonly used in business and management fields (). The literature review is limited to the sources published between January 2000 and January 2022. The studies that are included focus on RM, SMES, and information governance. The focus on information was based on research in the discipline of financial and management accounting.

Google scholar was used to search for articles from various sources such as EBSCO, Emerald, ProQuest, Science Direct, and Web of Science. The searching criteria were narrowed by using the key words “Risk Management” and “Small Medium Enterprises” to access the journals covering RM in SMEs. The other words used for a search in the topic were (information for governance*), (information governance*), (enterprise risk management*), (management accounting information in SMEs*), and (financial accounting information in SMEs*).

Ultimately, 168 articles were identified as being in line with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the most relevant articles were selected. Duplicated articles were eliminated, and book reviews were also excluded. Full text articles were glanced through to evaluate the quality and eligibility of the research. The journal articles published by reputable publishers were included in the review with well-cited references. The articles that were peer-reviewed and published in reputable journals were selected. In total, 78 studies were included in this research.

These 78 studies were reviewed to identify what has been written and researched on the topic of RM in SMEs from a broad perspective. The 78 studies included studies that have developed SME RM frameworks and models with a focus on the simplification of ERM implementation in SMEs considering the limitation of resources, and the RM processes and business strategies were individually scrutinised with the purpose of determining a common ground on the subject. The reason these studies were further analysed was to get an insight into the information governance aspects covered in these studies. The components of the conceptual RMF for SMEs were identified, in which 14 variables were recognised based on the literature. The conceptual framework is made up of fundamentals which lay the foundation and pillars that support the framework. The findings of the research are the common ground of the studies reviewed and the components of the conceptual RMF for SMEs (SMERMF).

5. Findings

The findings are discussed in two sub-sections: the common ground of the studies on ERM and the components of an RMF for SMEs.

5.1. Common Ground of the Studies on ERM

The studies reviewed agree that ERM is critical to SMEs for their growth and sustainability. The common ground for the studies reviewed is the challenges of SMEs, which are the limitation of resources, the need to simplify ERM for SMEs, and the need for guidelines. They all acknowledge the fact that there are different factors that impact the implementation of ERM in SMEs which still need to be researched. All the studies reviewed advocate for the need for more research to be conducted on ERM for SMEs. However, according to the researchers, no study researched information governance leading to ERM in SMEs. Information and communication form part of the components of the COSO ERM framework (henceforth referred to as the COSO ERM) and are also incorporated into some of the studies reviewed. The COSO ERM () is based on five (5) components, namely: governance and culture; strategy and objective setting; performance; review and revision; and information, communication and reporting. Management uses the COSO ERM widely for the improvement of the management of uncertainty and the identification of risk appetite to increase value. Furthermore, the COSO ERM defined internal control as “a process, effected by an entity’s board of directors, management and other personnel, designed to provide reasonable assurance of the achievement of objectives in the following categories: effectiveness and efficiency of operations, reliability of financial reporting, compliance with applicable laws and regulations.” The reliability of financial reporting therefore relies on information. However, not much is unpacked in previous studies on which information is imperative to SMEs for RM, what sources of information there are, and how it feeds into the enhancement of business strategy and operational strategy. The current research is aiming to tap into the crux of what constitutes the risk types. Information governance may not be isolated from risk monitoring and reporting, even for risk mitigation actions/strategies. Therefore, the current research aims at research information governance as the piece that might contribute to the simplification of ERM in SMEs and unpack its connectivity to financial strategy and monitoring. In order to maintain the logic of the research, and due to the fact that information as a concept is too wide, the focus is narrowed to accounting information. The components of the conceptual framework will be discussed in Section 5.2.

5.2. Components of the Conceptual Framework

Information governance, as the processes, people, technologies, and all other strategies to manage information (), is presented in the proposed SMERMF as the centre that holds all other components together. However, the mapping of the elements for information governance to the basics (fundamentals) and support (pillars) of RM makes the case for the current research. Financial strategies such as working capital management, cash flow management, and business processes such as planning, which are management accounting techniques (), cement the components of the SMERMF. The performance of the enterprise is demonstrated by the ability of the enterprise to meet its goals () and therefore forms part of the SMERMF. Financial Accounting stands out as a discipline given that annual financial statements are prescribed by the IFRS as a source of accurate, complete, and timely information (). According to (), the lack of risk oversight is one of the factors that has not received attention from researchers although it may have a negative impact on the sustainability of SMEs. As such, the current research incorporates oversight as a component for the SMERMF. The components of the SMERMF will not be complete without examining the culture in the enterprise that informs information governance () and the internal controls that are confirmed to enhance the sustainability of SMEs (). Information governance will be discussed next.

- Information Governance

Information governance is the management of records, the privacy of information, information freedom, and e-discovery (). The goal of information governance is to provide integrated, timely, complete, secure, and consistent information (). According to (), it is not possible for an entity to operate effectively and efficiently without information governance. Information governance comprises information, business processes, compliance, and people management (). The implementation of information governance policies is not successful due to the silo approach of managing business processes and information ().

The business world is becoming complex, and SMEs are required to understand the principles of information governance to thrive (). Information governance is a necessity and drives the success of an enterprise (). The role and relevance of record management in running the day-to-day operations of the enterprise are raised by (). Her results confirm the undisputable relationship between information governance and records management. As such, there might be a need for good information governance in SMEs that may form a stronghold for RM for their sustainability. SMEs may need to understand the principle of information governance in their enterprises and take care of the components that feed into information governance.

- Information

Information is a source of influence and imminent power (). () assert that data quality is informed by information governance that is well defined for decision making. However, () viewed information governance from the perspective of technology, processes, people, and policy. Information governance is a holistic approach encompassing various strategies to provide quality information (). The current research focused on what kind of information may enhance the governance of information given that SMEs are not highly regulated like large enterprises.

- Financial Accounting

Financial accounting information is used by investors to classify and appraise investment opportunities (). The lack of reliable information may obstruct the flow of human and financial capital towards the business (). Quality financial accounting information allows investors and managers to determine the value creation prospect with less error and therefore improves efficacy (). According to (), it is financial accounting information that assists managers and investors to make a better selection of projects and abandon projects that are not earning returns. As such, financial accounting plays a crucial governance role through providing efficiencies in the management of assets and enhancing economic performance (). It might be crucial for SMEs to understand the governance role of financial accounting information and the value it adds to the business from an investor’s perspective, along with the management of organisational resources.

The availability of reliable and relevant information with regard to a business’ periodic performance, financial position, governance, and investment opportunities portrays transparency in the corporate and business world (). This transparency confirms the credibility and timeliness of disclosure, gives assurance to private acquisition, and ensures the quality of the enterprise (). Financial accounting information improves the information environment through unaudited disclosure and provides a contribution to the information processing activities of the world outside the enterprise (). The quality of financial information disclosure affects the cost of capital in which the cash flows are discounted and ultimately influences the cash flows (). Therefore, the vital governance role of financial information to boost economic performance may not be isolated in SMEs.

SMEs preparing annual financial statements and using them for decision making have more confidence about performance and financial status compared to those not preparing annual financial statements (). Financial statements provide insightful statistics regarding the likelihood of risks and returns, informing many decisions and playing a significant role in the success of the enterprise (). Financial statements are a reliable source of information that is used by both internal and external stakeholders including equity providers and lenders (). As much as the financial statements are used as a governing tool for financial accounting information (), they provide high-quality information within the integrative approach of information governance. Therefore, the preparation of annual financial statements is considered a component of the SMERMF.

The quality of published accounting information needs to be linked to issues on corporate governance. () reviewed how board composition affects the quality of information portrayed in the annual accounting earnings of listed enterprises. More conservative reporting of bad news and reporting earnings of higher quality were found in enterprises with more external board members. Although SMEs largely may not have boards, they still need to ensure the quality of the reporting of their earnings. () found that aggressive earnings management is less practiced in well-governed banks, and () also found a relationship between corporate governance and the quality of accounting information, thereby providing evidence that higher levels of accounting conservatism result from effective governance structures. Therefore, SMEs may also need to take note of the importance of information governance and governance structures.

- The accounting process

SMEs do not prioritise the implementation of the accounting process (). According to the study, the effective and efficient recording and reporting of financials are recommended for the success of SMEs. Recording and reporting can help SMEs’ owners to provide financial accounting information to determine the business performance and serve as the basis for allocating funds and decision making (). The failure of SMEs to do basic accounting leads to the inability to manage finances and adversely affects the progression of the enterprise (). If financial accounting information directly impacts information governance and the accounting process is the starting point in putting together the financial information, the accounting process is crucial to SMEs. Furthermore, according to (), business processes form part of the definition of information governance. Therefore, the accounting process as a business process is directly linked to information governance.

- Financial management process

Financial management is not just a critical element of business management; it is the most important (). () posits that financial management, especially working capital, is one of the challenges that SMEs are struggling with. SMEs tend to manage their finances in a different manner from large enterprises due to the size of their businesses (). They are of the view that SMEs are required to manage their finances in an almost similar manner to large enterprises. According to (), SMEs need to implement an appropriate accounting system and manage their working capital and cashflow well to ensure that they remain liquid and solvent.

The survival of an enterprise is dependent and centred around cashflow management () for the achievement of short- and long-term financial goals (). Although SMEs may have limited resources, () established that, during substantial financial turmoil, when enterprise risks might be high, a valuable tool to sustain the viability and financial performance of SMEs could be cash holdings and effective cash management. It is pertinent for SMEs to have an in-depth understanding of cashflow and forecasting as to when the money will be received or spent, ensuring the sales of products/services and timing together with estimates of the expected expenditure (). A failure to properly manage cashflow may put the enterprise at risk of collapse. As such, cashflow appears to balance the activities within the business and therefore forms part of the SMERMF.

Working capital is a significant element in SMEs that needs to be managed well, as most of the resources and assets may be in the form of current assets (). The performance, sustainability, and competitiveness of the enterprise are enhanced by the efficient and effective management of the working capital (). The primary role of working capital management is to ensure the efficient and effective management of resources to enhance the performance and, ultimately the profitability of the enterprise (). SMEs may need to focus their attention on the impact of working capital management to mitigate uncertainty in their level of working capital.

- Management Accounting

Management Accounting (MA) produces information that spearheads the core in assessing performance and evaluating the accountability of the enterprise, and it therefore serves as a control measure in a competitive operating environment (). Hence, MA techniques including budgeting, capital investment appraisals, and ratio analysis have since been used in managing business risk (; ). According to (), in the 21st century, the changes in the global trends of business networks, competition, and security markets that affect the business environment mandate new MA information. The current research aims to define the information that is essential for information governance leading to ERM in SMEs. MA techniques are described as control tools that are used to manage risk (). It might be imperative for SMEs to appreciate the value of this interdependence in relation to their growth and sustainability. As such, MA may be providing essential information for information governance and, ultimately, for managing risk.

RM is a feature of an enterprise’s life in all different forms of enterprises, whether it is listed or unlisted (). According to (), it is not a coincidence that attention has been paid to the role of MA in RM. The increased focus on RM stems from the importance of CG, detecting, measuring, treating, and observing risk, and the competence of management controls (). RM should be approached from a holistic perspective, as risk affects each aspect of the enterprise (). () directly links the position of MA to RM. In agreement, () emphasise the proactive role of management accountants in connecting and collaborating risk control. Therefore, there is an emphasis on MA in RM. It might be essential for SMEs to start appreciating this connection. As such, MA, under the umbrella of accounting information, is considered an important component of information governance that leads to ERM.

- Streamlined Business Processes

Business process management (BPM) is linked to the framework of organising, systematising, arranging, classifying, and categorising the day-to-day processes, incorporating the appropriate means with a goal of enabling the enterprise to add value to the enterprise (). The business processes are critical to the operational efficiencies of the enterprise (). It is important to manage the business processes in such a manner that they complement the corporate strategy, support operational efficiency, and enhance the competitive advantage (). Streamlined business processes in an enterprise result in profitability, good customer relations, efficiencies, proper cost management, accountability, and the enhancement of market competitiveness (). () argue that BPM is equally as important to SMEs as it is to large enterprises. As such, business processes are important for the sustainability of the enterprise, regardless of its size. A failure to ensure that business processes are streamlined appears to be a risk to the enterprise and, therefore, is considered imperative to the RMF for SMEs.

- Planning

Budgetary planning, as a component of MA, enables the enterprise to have insight into its market position in the short term and provides feedback on performance (). Hence, budgetary planning in the 21st century has adopted the identity of being a strategic tool that is collaborating with both the external and internal strategic environment of the enterprise (). As much as a budget is a planning and controlling mechanism, management needs to be clear as to what needs to be achieved during the short and long term (). A budget is critical in setting the direction with regard to planning, assessment, organising, communication, and, eventually, decision making for an enterprise (). Proper budgetary planning is essential for the achievement of the enterprises’ objectives (). As such, planning is considered imperative for the RM for SMEs.

- Performance measurements

The performance of the enterprise is demonstrated by the ability of the enterprise to meet its goals (). It is relevant for the enterprises’ performance to be gauged against the practices, values, and strategies for any well-performing enterprise in the world (). Nevertheless, () suggest that innovation is an influential factor for SMEs’ performance. Therefore, the views seem to differ when it comes to a proper approach of measuring the performance of the enterprise. However, there seem to be a common ground that the enterprise’s performance needs to be measured. As such, performance measurement appears to be important to the enterprise irrespective of its size and, therefore, forms part of the SMERMF.

The results of () illustrate that SMEs that are using the balance scorecard (BSC) are performing better financially and are good at innovation. The BSC is three-in-one, as it incorporates performance measurement, a control system, and strategic management techniques (). The benefits of the BSC for integrating measurements for both the financial and non-financial aspects of the business and the amalgamation of the structure, vision, and strategy are some of the traits that makes the system popular (). () tested the use of the BSC in SMEs and concluded that SMEs can benefit from using the system. According to (), the implementation of the BSC is possible in SMEs provided that the specific conditions and requirements of the entity are considered. However, the results of the study further indicate that, in order to successfully implement the BSC in SMEs, the process of designing the system should be simplified to accommodate the adjustment to the characteristics of SMEs. () found that company performance can be enhanced by applying the BSC, and challenges can be overcome by management and employees. () established that employees that attended training programs attained more skills and abilities, and, when implementing the BSC in a municipal sporting entity, effective performance management and future sustainability were achieved. Nevertheless, the BSC seems to be an integrative performance measurement that is good for performance measurements irrespective of whether it is viably applicable to SMEs or not.

- Culture

Information governance experts believe that the provision of accurate information is driven by the control characteristics of the enterprise’s culture (), and effectiveness of information governance is informed by the culture of the enterprise. Enterprise culture also empowers the adoption of change for the implementation of information governance (). Ignoring the enterprise culture during change management may result in the unsuccessful implementation of information governance (). The relationship between human beings and information defines the culture of the enterprise (). () argue that information governance is influenced by organisational and social requirements. As such, the culture in the enterprise informs the governance of information (). Therefore, it might be important to scrutinise the culture in SMEs and see how it impacts information governance, as the culture in small enterprises may differ from that of large enterprises.

- Internal Controls

The effectiveness of internal controls ensures that decisions are taken based on correct information and improve the efficiencies in operations (). According to (), internal controls align the efficiencies in the allocation of resources, providing efficiencies in operations. Internal controls are used as a governance tool in retaining the customer–supplier relationship (), controlling excessive executive compensation (), and safeguarding the resources of the enterprise (). The value that is added by the internal controls in the enterprise may not be ignored by SMEs. Internal controls tap into almost all the aspects of the enterprise, which echoes the fact that it is a governance tool (). SMEs acknowledge the value of implementing a system of internal controls in their enterprises (). As such, it might be worthwhile to look at this interconnection of internal controls and information governance in SMEs.

- Oversight

The size of the enterprise informs the execution of the oversight function instrument (). External auditors, certified fraud examiners, audit committees, internal audits, boards of directors, and management are the structures that perform oversight processes in large enterprises (). The challenge in SMEs is that they might not have all these structures. In some cases, there is no differentiation between the managers, executive managers, and owners of the enterprise in SMEs (). Given the lack of differentiation between executive managers and owners in some SMEs, the duty of ensuring the culture of control and the integrity of the business resides with executive management (). The lack of risk oversight is one of the factors that has not received attention from researchers; however, it may have a negative impact on the sustainability of SMEs (). As such, a one-size-fits-all oversight model might not work for both large enterprises and SMEs. There may be a need for guidelines on how SMEs may enforce oversight in their enterprises, irrespective of the limited resources. Furthermore, it might be imperative to obtain an insight into the impact of the oversight on RM and its connection to the sustainability and growth of SMEs. Therefore, oversight forms a component of the SMERMF.

- Leveraging information technology

Information technology drives and reinforces successful economies (). The artificial intelligence and cloud-based systems among information technology (IT) mechanisms are now the enablers for businesses, irrespective of whether they are small, medium, or large enterprises or in the private or public sectors (). Equally so, this increases the exposure to cyber-attacks, resulting in the interruption of the day-to-day running of the business and, ultimately, financial loss (). The privacy of information is violated by these cyber-attacks, and it therefore might not be possible to exclude information technology from information governance in SMEs. Leveraging information technology forms part of the components of the COSO ERM under information, communication, and reporting ().

It might not be disputed that IT and cyber risks are part and parcel of operation risks (). Furthermore, SMEs are often characterised by a lack of resources (). The lack of knowledge in certain areas of expertise is one of the factors that also hinders their growth (). According to (), there is a lack of technical knowledge about the tools that may be used to address cyber security challenges in SMEs. However, organisations that are investing in information technology specialists are better equipped to mitigate the cyber risks and also devise better internal policies and guidelines to reduce the costs of cyber incidents (). Transferring the cyber security risk to a third-party service provider is the mechanism that is used by some organisations to benefit from the economies of scale for using similar service providers (). As such, it is important for SMEs, especially in the 21st century, to leverage information and technology for their own sustainability.

- Risk assessment and risk appetite

Risk assessment is the central aspect for an RMF and is fundamental to the whole process (). It is crucial for SMEs to conduct risk assessments. However, this should be accurately performed; otherwise, it may serve no purpose (). According to (), risks are linked to objectives that might be impacted and are evaluated inherently and residually. Risk assessment is considered imperative and should form part of the SMERMF.

Risk appetite has a direct impact on returns to the business (). The fact that the business is operating exposes the entity to business and financial risk (). The exposure to business and financial risks is not only limited to large enterprises, however; it is equally applicable to SMEs. As such, all the business operations, irrespective of the size and whether the business is in a developed or developing country, need to take into account its risk appetite and also perform a risk assessment for their own sustainability and survival.

The risk appetites for different sectors and operations are not alike (). According to (), a comparison between the managers from developed and developing countries demonstrates that the managers from developed countries take more risk compared to those from developing countries, which illustrates that the risk appetite varies with individual cultures. (), concluded that male-owned SMEs have a greater risk appetite compared to female-owned SMEs. The risk appetite may vary based on age, gender, resources, level of knowledge, and the available tools that may assist the SMEs in the subject of RM. As such, risk appetite is fundamental to SMERMF.

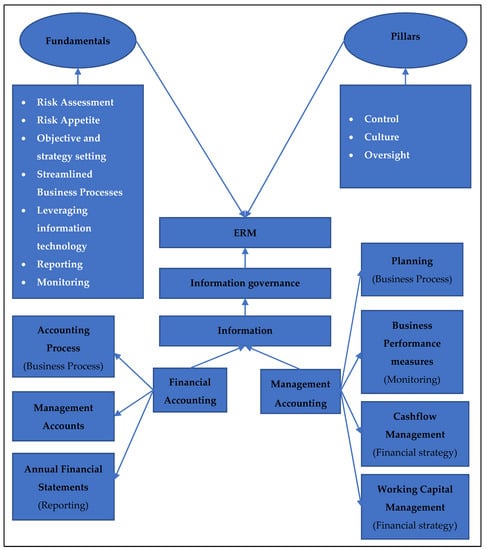

Figure 1 presents the conceptual RMF for SMEs. It summarises the conceptual RM framework for SMEs and illustrates all the building blocks that are the components of the RMF. The first block contains the fundamentals of the RMF for SMEs. For the purpose of this research, the fundamentals are the basic principles of RM in SMEs. Control, oversight, and culture support the SMERMF as pillars. The pillars mean the activities or the essentials of the backbone of RM in SMEs. Both fundamentals and pillars directly impact the ERM. However, fundamentals overlap in directly influencing the elements of information that impact the information governance and, ultimately, the ERM. Among the fundamentals, the determination of risk appetite for the entity and risk assessment are complementary and are a foundation to ERM, whereas the reporting of risk indicators cannot be isolated from the monitoring of risk.

Figure 1.

Conceptual SMERMF. Source: Author’s own.

All of the components discussed are mapped in Figure 1, demonstrating the connection of business processes, financial strategies, and the monitoring of risk to the fundamentals. Furthermore, Figure 1 illustrates how the components of the SMERMF affiliate with the fundamentals and pillars of RMF, while some of these components are the elements of information sources that feed into information governance and, ultimately, ERM. The intention of this RMF is to be usable in any SMEs irrespective of size and sector. SMEs may use this RMF through setting the fundamentals as a foundation, allowing the pillars to support RM, implementing financial strategies, aligning business processes, and monitoring the risk.

6. Conclusions

Since information is crucial to all sizes of enterprises, information governance should play an important role. As such, the need for good information governance in SMEs to ensure RM for their sustainability has been incorporated into the framework. SMEs may need to be made aware of the principle of information governance and how to take care of the components that feeds into information governance. In this article, financial information has been in the centre of information governance. It might therefore be important for SMEs to understand the governance role of financial accounting information and the value it adds to the business from an investor’s perspective, along with the management of organisational resources. SMEs need to address the accounting process, or lack thereof, as well as the financial management and management accounting within their enterprises in order to manage risk in the enterprises. When SMEs streamline their business processes, risk can also be reduced. Another way to manage risk is to ensure that planning takes place in the form of budgets and to leverage information technology. Performance measurement is also important since an enterprise, whether large or small, should be able to measure their performance to ensure they remain sustainable. The culture of the enterprise, internal controls, and oversight are important pillars on the basis of which an enterprise should manage their risk. Each SME should conduct a risk assessment and know their risk appetite to ensure they know how far they are willing to go to be competitive and sustainable. Having objectives and strategies in place will also assist in the management of risk. The contribution of the article is to provide an RM guide to SMEs on the interconnectivity of risk with the objective setting, financial processes, financial strategy, and monitoring, including strategic context positioning. This intends to address the challenge of adopting a holistic approach to RM in SMEs, which is one of the major causes of small business’ failures in developing countries. Furthermore, the article provides an RM tool to SMEs that is inclusive and does not focus on a specific functional area or sector, assessing the dimensions of risk within the spectrum of information governance. As much as SMEs have limited resources, based on the findings of this research, it might be possible to adopt a holistic approach in their RM through managing the aspects of information governance. This may assist SMEs with risk assessment, aligning their risk appetite and using ERM for their own survival and sustainability. The limitation of the research is its focus on internal information, and it is recommended that future studies analyse the aspect of external information.

Future work will entail distributing a questionnaire to SMEs based on the developed framework to enhance the framework, followed by conducting focus groups to validate the final framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z.F.M., H.M.v.d.P. and M.F.T.; methodology, H.M.v.d.P. and M.F.T.; validation, Z.Z.F.M., H.M.v.d.P. and M.F.T.; formal analysis, Z.Z.F.M.; investigation, Z.Z.F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.F.M.; writing—review and editing, H.M.v.d.P. and M.F.T.; visualization, Z.Z.F.M., H.M.v.d.P. and M.F.T.; supervision, H.M.v.d.P. and M.F.T.; project administration, H.M.v.d.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external fundings.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abubakar, Yazid Abdullahi, Chris Hand, David Smallbone, and George Saridakis. 2019. What Specific Modes of Internationalization Influence SME Innovation in Sub-Saharan Least Developed Countries (LDCs)? Technovation 79: 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, Emrah, and Yasemin Göç. 2011. Prediction of Risk Perception by Owners’ Psychological Traits in Small Building Contractors. Construction Management and Economics 29: 841–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrifa, Godfred Adjapong. 2016. Net Working Capital, Cash Flow and Performance of UK SMEs. Review of Accounting and Finance 15: 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Shamim, and Yanping Liu. 2018. SME Managers and Financial Literacy; Does Financial Literacy Really Matter? Journal of Public Administration and Governance 8: 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alade, Muyiwa Ezekiel, and Mercy Oluwatoyin Owabumoye. 2020. Budgetary Control Mechanism and Financial Accountability in Ondo State Public Sector. Accounting & Taxation Review 4: 134–37. [Google Scholar]

- Aldasoro, Iñaki, Leonardo Gambacorta, Paolo Giudici, and Thomas Leach. 2022. The Drivers of Cyber Risk. Journal of Financial Stability 60: 100989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibhai, Salim, Erwin Bakker, T. V. Balasubramanian, Kunal Bharadva, Asif Chaudhry, Danie Coetsee, James Dougherty, Chris Johnstone, Patrick Kuria, Christopher Naidoo, and et al. 2020. Interpretation and Application of IFRS Standards. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Aliona, Birca. 2016. Financial Performance Measurement Tools. Annals-Economy Series 3: 169–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ameen, Ahmed Mohamed, Moataz Fathi Ahmed, and Meral Ahmed Abd Hafez. 2018. The Impact of Management Accounting and How It Can Be Implemented into the Organizational Culture. Dutch Journal of Finance and Management 2: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, Nasrin, Zarina Zakaria, and Noor Adwa Sulaiman. 2019. The Quality of Accounting Information: Relevance or Value-Relevance? Asian Journal of Accounting Perspectives 12: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Wendy J., and Janet A Samuels. 2018. Analyzing Two Investments—An Instructional Case to Introduce Basic Financial Accounting Concepts. Issues in Accounting Education 33: 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Andrew M., Darren Henderson, and Daniel P. Lynch. 2017. Supplier Internal Control Quality and the Duration of Customer-Supplier Relationships. The Accounting Review 93: 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensaada, Ilies, and Noria Taghezout. 2019. An Enterprise Risk Management System for SMEs: Innovative Design Paradigm and Risk Representation Model. Small Enterprise Research 26: 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlinger, Edina, and Kata Váradi. 2015. Risk Appetite. Public Finance Quarterly 60: 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Borocki, Jelena, Mladen Radišić, Włodzimierz Sroka, Jolita Grėblikaitė, and Armenia Androniceanu. 2019. Methodology for Strategic Posture Determination of SMEs. Engineering Economics 30: 265–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Chris. 2019. Introductory Econometrics for Finance, 4th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, Juan-Pierré, and André van den Berg. 2017. The Conduciveness of the South African Economic Environment and Small, Medium and Micro Enterprise Sustainability: A Literature Review. Expert Journal of Business and Management 5: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bure, Makomborero, and Robertson Khan Tengeh. 2019. Implementation of Internal Controls and the Sustainability of SMEs in Harare in Zimbabwe. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 7: 201–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Qiang, Beng Wee Goh, and Jae B. Kim. 2018. Internal Control and Operational Efficiency. Contemporary Accounting Research 35: 1102–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiwamit, Pimsiri, Sven Modell, and Robert W. Scapens. 2017. Regulation and Adaptation of Management Accounting Innovations: The Case of Economic Value Added in Thai State-Owned Enterprises. Management Accounting Research 37: 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). 2017. ERM–Integrating with Strategy and Performance. New York: COSO. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, David J., Mahmoud Ezzamel, and Sandy Q. Qu. 2017. Popularizing a Management Accounting Idea: The Case of the Balanced Scorecard. Contemporary Accounting Research 34: 991–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovini, Chiara, Gabriele Santoro, and Giovanni Ossola. 2021. Rethinking Risk Management in Entrepreneurial SMEs: Towards the Integration with the Decision-Making Process. Management Decision 59: 1085–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, Ranjan, Xinghua Gao, and Yonghong Jia. 2017. Internal Control and Internal Capital Allocation: Evidence from Internal Capital Markets of Multi-Segment Firms. Review of Accounting Studies 22: 251–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshmandnia, Ali. 2019. The Influence of Organizational Culture on Information Governance Effectiveness. Records Management Journal 29: 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darma, Jufri, Azhar Susanto, Sri Mulyani, and Jadi Suprijadi. 2018. The Role of Top Management Support in the Quality of Financial Accounting Information Systems. Journal of Applied Economic Sciences 13: 1009–20. [Google Scholar]

- Davids, Heinrich, and Osden Jokonya. 2019. Investigating Factors Influencing ICT Adoption among SMES in the Hospitality Industry in the Western Cape. In Shifting the Digital Skills Discourse for the 4th Industrial Revolution. Boksburg: National Electronic Media Institute of South Africa (NEMISA), pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- del Carmen Gutiérrez-Diez, María, José Luis Bordas Beltran, and Ana María de Gpe Arras-Vota. 2022. Sustainable Balance Scorecard as a CSR Roadmap for SMEs: Strategies and Architecture Review. In Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurial Leadership and Competitive Strategy in Family Business. Edited by José Manuel Saiz-Álvarez and Jesús Manuel Palma-Ruiz. London: IGI Global, pp. 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Ping. 2012. The Internationalization of Chinese Firms: A Critical Review and Future Research*. International Journal of Management Reviews 14: 408–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deni, Asep, and Ari Riswanto. 2019. Analysis of Factors That Influence The Disclosure Of Enterprise Risk Management in SMEs. Jurnal Konsep Bisnis Dan Manajemen 6: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, Panagiotis E., and Dimitrios Asteriou. 2010. The Effect of Board Composition on the Informativeness and Quality of Annual Earnings: Empirical Evidence from Greece. Research in International Business and Finance 24: 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, Panagiotis E., Ioannis Kosmas, and Ioannis Douvis. 2017. Implementing the Balanced Scorecard in a Local Government Sport Organization. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 66: 362–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, Panagiotis E., Konstantinos Koronios, Alkis Thrassou, and Demetris Vrontis. 2020. Cash Holdings, Corporate Performance and Viability of Greek SMEs: Implications for Stakeholder Relationship Management. EuroMed Journal of Business 15: 333–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Division on Investment and Enterprise of UNCTAD. 2016. Investor Nationality: Policy Challenges. In World Investment Report 2016. Geneva: UNCTAD, vol. 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Linying, and Karim Keshavjee. 2016. Why Is Information Governance Important for Electronic Healthcare Systems? A Canadian Experience. Journal of Advances in Humanities and Social Sciences 2: 250–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubihlela, Job, and Lisa Nqala. 2017. Internal Controls Systems and the Risk Performance. International Journal of Business and Management Studies 9: 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dudic, Zdenka, Branislav Dudic, Michal Gregus, Daniela Novackova, and Ivana Djakovic. 2020. The Innovativeness and Usage of the Balanced Scorecard Model in SMEs. Sustainability 12: 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito, Alfonso, and Juan A. Sanchis-Llopis. 2019. The Relationship between Types of Innovation and SMEs’ Performance: A Multi-Dimensional Empirical Assessment. Eurasian Business Review 9: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falle, Susanna, Romana Rauter, Sabrina Engert, and Rupert J. Baumgartner. 2016. Sustainability Management with the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard in SMEs: Findings from an Austrian Case Study. Sustainability 8: 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira de Araújo Lima, Priscila, Maria Crema, and Chiara Verbano. 2020. Risk Management in SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Directions. European Management Journal 38: 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figl, Kathrin. 2017. Comprehension of Procedural Visual Business Process Models: A Literature Review. Business and Information Systems Engineering 59: 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, John R. S., and Betty J. Simkins. 2016. The Challenges of and Solutions for Implementing Enterprise Risk Management. Business Horizons 59: 689–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Xinghua, and Yonghong Jia. 2016. Internal Control over Financial Reporting and the Safeguarding of Corporate Resources: Evidence from the Value of Cash Holdings. Contemporary Accounting Research 33: 783–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatzert, Nadine, and Joan Schmit. 2016. Supporting Strategic Success through Enterprise-Wide Reputation Risk Management. The Journal of Risk Finance 17: 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geer, Dan, Eric Jardine, and Eireann Leverett. 2020. On Market Concentration and Cybersecurity Risk. Journal of Cyber Policy 5: 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorondutse, Abdullahi Hassan, Rahima Abass Ali, Ahmed Abubakar, and Muhammad Nura Ibrahim Naalah. 2017. The Effect of Working Capital Management on SMEs Profitability in Malaysia. Polish Journal of Management Studies 16: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzeń-Mitka, Iwona. 2019. Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach to Analyze the Interaction Among Key Factors of Risk Management Process in SMEs: Polish Experience. European Journal of Sustainable Development 8: 339–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Melanie J. 2014. On the Inside Looking In: Methodological Insights and Challenges in Conducting Qualitative Insider Research. The Qualitative Report 19: 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, Athambawa, Samsudeen Sabraz Nawaz, and Ahamed Lebbe Mohamed Ayoobkhan. 2020. Determinant of Contingency Factors of AIS in ERP System. Test Engineering and Management 83: 6592–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hanifah, Haniruzila, Hasliza Abdul Halim, Noor Hazlina Ahmad, and Ali Vafaei-Zadeh. 2019. Emanating the Key Factors of Innovation Performance: Leveraging on the Innovation Culture among SMEs in Malaysia. Journal of Asia Business Studies 13: 559–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, Karen. 2014. Enterprise Risk Management: A Guide for Government Professionals. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Harl, Maximilian, Sven Weinzierl, Mathias Stierle, and Martin Matzner. 2020. Explainable Predictive Business Process Monitoring Using Gated Graph Neural Networks. Journal of Decision Systems 29: 312–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havierniková, Katarína, and Małgorzata Okręglicka. 2019. The Difference in Organization of Risk Management between Slovak and Polish SMEs. Social & Economic Revue 17: 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- He, Chenyang, and Kevin Lu. 2018. Risk Management in Smes with Financial and Nonfinancial Indicators Using Business Intelligence Methods. In Ntegrated Economy and Society: Diversity, Creativity and Technology; Proceedings of the MakeLearn and TIIM International Conference 2018. Naples: ToKnowPress, pp. 405–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkin, Paul. 2014. Fundamentals of Risk Management: Understanding, Evaluating and Implementing Effective Risk Management, 3rd ed. London: Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- Hudakova, Maria, Matej Masár, and Vladimír Míka. 2019. Assessing the Needs of Risk Management Eduction in the World. Paper presented at 12th Annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, Spain, November 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hutaibat, Khaled, and Zaidoon Alhatabat. 2020. Management Accounting Practices’ Adoption in UK Universities. Journal of Further and Higher Education 44: 1024–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibiwoye, Ade, Joseph Mojekwu, and Francis Dansu. 2020. Enterprise Risk Management Practices and Survival of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Nigeria. Studies in Business and Economics 15: 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, Siti Musliha Mohd, and Azizan Abdullah. 2016. A Conceptual Framework on Determinants of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) Adoption: A Study in Manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) BT. In Proceedings of the 1st AAGBS International Conference on Business Management 2014 (AiCoBM 2014). Edited by Jaafar Pyeman, Wan Edura Wan Rashid, Azlina Hanif, Syed Jamal Abdul Nasir Syed Mohamad and Peck Leong Tan. Singapore: Springer, pp. 245–55. [Google Scholar]

- In, Joonhwan, Randy Bradley, Bogdan C. Bichescu, and Chad W. Autry. 2019. Supply Chain Information Governance: Toward a Conceptual Framework. The International Journal of Logistics Management 30: 506–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International financial reporting Standards (IFRS). 2016. A Guide through International Financial Reporting Standards. London: IFRS Foundation Publication Department United Kingdom.

- Isa, Azman Mat, Sabri Mohd Sharif, Rabiah Mohd Ali, and Nordiana Mohd Nordin. 2019. Managing Evidence of Public Accountability: An Information Governance Perspective. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change 10: 142–53. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, Ariful, and Des Tedford. 2012. Risk Determinants of Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturing Enterprises (SMEs)—An Exploratory Study in New Zealand. Journal of Industrial Engineering International 8: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehinde, Adesina, Alabi Opeyemi, A. Benjamin, Ogunjobi Adedayo, and O. A. Abel. 2017. Enterprise Risk Management and the Survival of Small Scale Businesses in Nigeria. International Journal of Accounting Research 5: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki-Aries, Duncan, and Shamal Faily. 2017. Persona-Centred Information Security Awareness. Computers and Security 70: 663–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, YoungJun, and Nicholas S. Vonortas. 2014. Managing Risk in the Formative Years: Evidence from Young Enterprises in Europe. Technovation 34: 454–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintu, Ismail, Patricia Naluwooza, and Y. Kiwala. 2019. Cash Inflow Conundrum in Ugandan SMEs: A Perspective of ISO Certification and Firm Location. African Journal of Business Management 13: 274–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwarteng, Amoako. 2018. The Impact of Budgetary Planning on Resource Allocation: Evidence from a Developing Country. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 9: 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Fong-Woon, and Muhammad Kashif Shad. 2017. Economic Value Added Analysis for Enterprise Risk Management. Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal 9: 338–47. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Ben. 2019. Working Capital Management and Firm’s Valuation, Profitability and Risk. International Journal of Managerial Finance 15: 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Thi Tam. 2020. Performance Measures and Metrics in a Supply Chain Environment. Uncertain Supply Chain Management 8: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventis, Stergios, and Panagiotis Dimitropoulos. 2012. The Role of Corporate Governance in Earnings Management: Experience from US Banks. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 13: 161–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventis, Stergios, Panagiotis Dimitropoulos, and Stephen Owusu-Ansah. 2013. Corporate Governance and Accounting Conservatism: Evidence from the Banking Industry. Corporate Governance: An International Review 21: 264–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, Christina. 2018. Enterprise Risk Management In Banking Industry. FIRM: Journal of Management Studies 3: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, Cong, Hua Duan, Qingtian Zeng, Mengchu Zhou, Faming Lu, and Jiujun Cheng. 2019. Towards Comprehensive Support for Privacy Preservation Cross-Organization Business Process Mining. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 12: 639–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llivisaca, Juan Carlos, Diana Jadan, Rodrigo Guamán, Rodrigo Arcentales-Carrion, Mario Pena, and Lorena Siguenza-Guzman. 2020. Key Performance Indicators for the Supply Chain in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Based on Balance Score Card. Test Engineering and Management 83: 25933–45. [Google Scholar]

- López-Pintado, Orlenys, Marlon Dumas, Luciano García-Bañuelos, and Ingo Weber. 2019. Interpreted Execution of Business Process Models on Blockchain. Paper presented at 2019 IEEE 23rd International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference (EDOC), Paris, France, October 28–32; pp. 206–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Qinghua, An Binh Tran, Ingo Weber, Hugo O’Connor, Paul Rimba, Xiwei Xu, Mark Staples, Liming Zhu, and Ross Jeffery. 2021. Integrated Model-Driven Engineering of Blockchain Applications for Business Processes and Asset Management. Software: Practice and Experience 51: 1059–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyngstadaas, Hakim, and Terje Berg. 2016. Working Capital Management: Evidence from Norway. International Journal of Managerial Finance 12: 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma’aji, Muhammad M., Nur Adiana Hiau Abdullah, and Karren Lee-Hwei Khaw. 2018. Predicting Financial Distress among SMEs in Malaysia. European Scientific Journal, ESJ 14: 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Malagueño, Ricardo, Ernesto Lopez-Valeiras, and Jacobo Gomez-Conde. 2018. Balanced Scorecard in SMEs: Effects on Innovation and Financial Performance. Small Business Economics 51: 221–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Muhammad Farhan, Mahbub Zaman, and Sherrena Buckby. 2017. Enterprise Risk Management and Firm Performance: Role of the Risk Committee. Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics 16: 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamai, Mbiki, and Song Yinghua. 2017. Enterprise Risk Management Best Practices for Improvement Financial Performance in Manufacturing SMEs in Cameroon. International Journal of Management Excellence 8: 1004–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martinez, Aurora, Juan-Gabriel Cegarra-Navarro, Alexeis Garcia-Perez, and Anthony Wensley. 2019. Knowledge Agents as Drivers of Environmental Sustainability and Business Performance in the Hospitality Sector. Tourism Management 70: 381–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mättö, Markus, and Mervi Niskanen. 2021. Role of the Legal and Financial Environments in Determining the Efficiency of Working Capital Management in European SMEs. International Journal of Finance & Economics 26: 5197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, Rafael D., and David Cababaro Bueno. 2017. Budgetary Control Processes towards Improved Service Delivery among Catholic Higher Educational Institutions: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Paper presented at 10th International Conference on Arts, Social Sciences, Humanities and Interdisciplinary Studies (ASSHIS-17), Manila, Philippines, December 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullon, Paul Anthony, and Mpho Ngoepe. 2019. An Integrated Framework to Elevate Information Governance to a National Level in South Africa. Records Management Journal 29: 103–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, Saqib, Rao Abrar Ahmad, and Azhar Ali. 2017. Impact of Financial Management Practices on SMEs Profitability with Moderating Role of Agency Cost. Information Management and Business Review 9: 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Guilla Sow, Abdoulaye, Rohaida Basiruddin, Jihad Mohammad, and Siti Zaleha Abdul Rasid. 2018. Fraud Prevention in Malaysian Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Journal of Financial Crime 25: 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naude, Micheline J., and Nigel Chiweshe. 2017. A Proposed Operational Risk Management Framework for Small and Medium Enterprises. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 20: a1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndungo, Jackson Mnago, and Mr. Kingford Rucha. 2017. Factors Affecting the Growth of Smes: A Study of Smes in Kajiado District. International Journal of Finance 2: 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. A. 2015. Small and Medium Enterprises Debt Financing in Vietnam. Kuala Lumpur: Asia Pacific University. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundana, Oyebisi M., Wisdom Okere, Ochuwa Ayomoto, David Adesanmi, Stephen Ibidunni, and Olusogo Ogunleye. 2017. ICT and Accounting System of SMEs in Nigeria. Management Science Letters 7: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebode, Oluwadare Joshua. 2018. Budget and Budgetary Control: A Pragmatic Approach to the Nigerian Infrastructure Dilemma. World Journal of Research and Review 7: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo, Tommaso. 2009. Integrating Risk and Performance in Management Reporting. Research Executive Summary Series 7: 12. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo, Tommaso. 2017. Risk and Performance Management: Two Sides of the Same Coin. In The Routledge Companion to Accounting and Risk. Edited by Margaret Woods and Philip Linsley. London: Routledge, p. 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletta, Angelo, and Genc Alimehmeti. 2016. SOX Disclosure and the Effect of Internal Controls on Executive Compensation. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 33: 277–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollman, Elizabeth. 2019. Corporate Oversight and Disobedience. Vanderbilt Law Review 72: 2013–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugnetti, Carlo, and Carlos Casián. 2021. Cyber Risks and Swiss SMEs: An Investigation of Employee Attitudes and Behavioral Vulnerabilities. Winterthur: ZHAW School of Management and Law, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rasouli, Mohammad Reza, Jos J. M. Trienekens, Rob J. Kusters, and Paul W. P. J. Grefen. 2016. Information Governance Requirements in Dynamic Business Networking. Industrial Management & Data Systems 116: 1356–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, Louis, François Bergeron, Anne-Marie Croteau, Ana Ortiz de Guinea, and Sylvestre Uwizeyemungu. 2020. Information Technology-Enabled Explorative Learning and Competitive Performance in Industrial Service SMEs: A Configurational Analysis. Journal of Knowledge Management 24: 1625–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Amin Ur, and Muhammad Anwar. 2019. Mediating Role of Enterprise Risk Management Practices between Business Strategy and SME Performance. Small Enterprise Research 26: 207–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, Simon, and Richard Ned Lebow. 2017. Influence and Hegemony: Shifting Patterns of Material and Social Power in World Politics. All Azimuth 6: 17–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rekarti, Endi, and Caturida Meiwanto Doktoralina. 2017. Improving Business Performance: A Proposed Model for SMEs. European Research Studies Journal 20: 613–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, John, Nigel Martin, and Bruce Gurd. 2007. Strategic Planning, Budget Monitoring and Growth Optimism: Evidence from Australian SMEs. BPS Competitive 1: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sadgrove, Kit. 2016. The Complete Guide to Business Risk Management, 3rd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Serag, Asmaa Abdelmonem, Mona Mohamed, and Ali Daoud. 2022. A Proposed Framework for Studying the Impact of Cybersecurity on Accounting Information to Increase Trust in The Financial Reports in the Context of Industry 4.0.: An Event, Impact and Response Approach. In Economic Challenges and Business Opportunities after the Corona Pandemic “A Future Vision” 6th Annual International Conference of Faculty of Commerce. Edited by Khalid Abdul Ghaffar, Zaki Mahmoud and Kamal Okasha. Al Masa: Tanta University, vol. 20, pp. 20–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shabbir, Malik Shahzad, and Okere Wisdom. 2020. The Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility, Environmental Investments and Financial Performance: Evidence from Manufacturing Companies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27: 39946–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, Asmat Ara, Anuj Kumar, Asif Ali Syed, and Mohammed Zafar Shaikh. 2021. A Two-Decade Literature Review on Challenges Faced by SMEs in Technology Adoption. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 25: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sipa, Monika. 2017. Innovation As a Key Factors of Small Business Competition. European Journal of Sustainable Development 6: 344–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, Robert F. 2014. Information Governance: Concepts, Strategies and Best Practices. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sonia, Lucya Erlinda, and Stefanie Gianto. 2018. The Role of Recording and Reporting Process of Basic Accounting in Small Medium Enterprises of Omah Duren Surabaya. JEMA: Jurnal Ilmiah Bidang Akuntansi Dan Manajemen 15: 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sroka, Włodzimierz, and Richard Szántó. 2018. Corporate Social Responsibility and Business Ethics in Controversial Sectors: Analysis of Research Results. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation 14: 111–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszkiewicz, Piotr, and Aleksander Werner. 2021. Reporting and Disclosure of Investments in Sustainable Development. Sustainability 13: 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Too, Eric, Tiendung Le, and Wei Yee Yap. 2017. Front-End Planning—The Role Of Project Governance And Its Impact On Scope Change Management. International Journal of Technology 8: 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vanauken, Howard, Semra Ascigil, and Shawn Carraher. 2016. Turkish SMEs’ Use of Financial Statements for Decision Making. The Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance 19: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Vigario, F. 2007. Managerial Accounting, 4th ed. Durban: LexisNexis. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Liangcheng, Yining Dai, and Yuye Ding. 2019. Internal Control and SMEs’ Sustainable Growth: The Moderating Role of Multiple Large Shareholders. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12: 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, John, and Rick Newby. 2005. Biological Sex, Stereotypical Sex-roles, and SME Owner Characteristics. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 11: 129–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakob, Sajiah, B. A. M. Hafizuddin-Syah, Rubayah Yakob, and Nur Raziff. 2019. The Effect of Enterprise Risk Management Practice on SME Performance. The South East Asian Journal of Management 13: 151–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yathiraju, Nikhitha. 2022. Investigating the Use of an Artificial Intelligence Model in an ERP Cloud-Based System. International Journal of Electrical, Electronics and Computers 7: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaefarian, Reza, Misagh Tasavori, Teck-Yong Eng, and Mehmet Demirbag. 2020. Development of International Market Information in Emerging Economy Family SMEs: The Role of Participative Governance. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, Namig Alizadeh, and Leyla Mammadova Vagif. 2020. Role of Management Accounting in the Organization. Paper presented at 55th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development, Baku, Azerbaijan, June 18–19; pp. 367–72. [Google Scholar]

- Žigienė, Gerda, Egidijus Rybakovas, and Robertas Alzbutas. 2019. Artificial Intelligence Based Commercial Risk Management Framework for SMEs. Sustainability 11: 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, Grzegorz. 2020. Working Capital Management Strategies in Polish SMEs. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal 24: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).