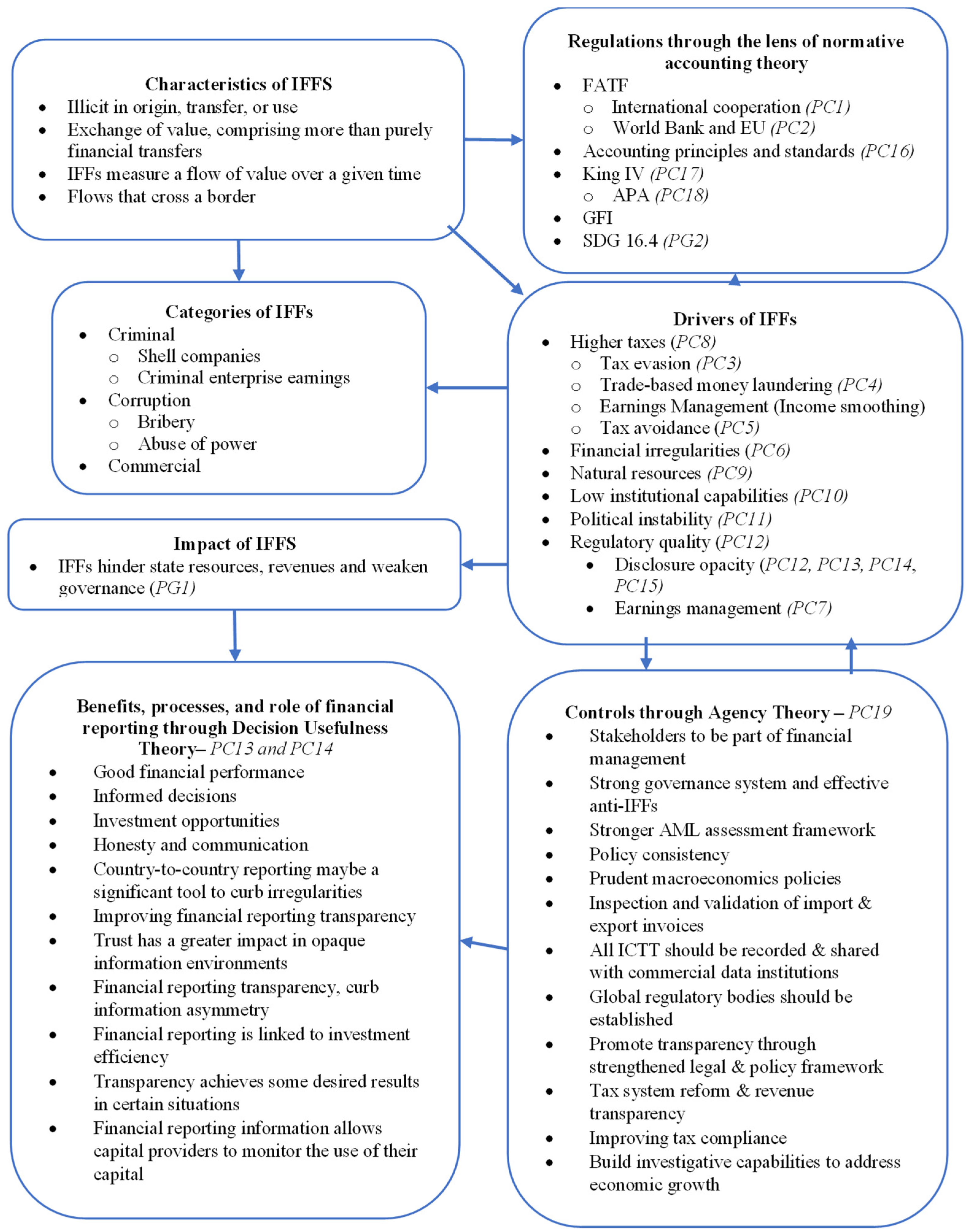

A Conceptual Framework to Analyse Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Questions and Objective

- What are the characteristics of illicit financial flows (IFFS)? (RQ1)

- What are the categories and drivers of IFFs? (RQ2)

- How may IFFs be addressed? (RQ3)

- Develop a conceptual framework to assist with the curbing of IFFs. (Obj)

1.2. The Use of Propositions

- Content propositions indicate the guiding principles defining the entities (round blocks) in our framework. Content propositions are indicated by PC1, PC2, … PCn, with n representing a natural number.

- General propositions indicate aspects of a more general nature and are indicated by PG1, PG2, … PGm, with m representing a natural number.

1.3. Theoretical Lens of This Work

2. Results

2.1. The Current Conceptual Financial Reporting Framework

2.1.1. A Brief of the Financial Reporting Problem

2.1.2. Conceptualising Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs)

- IFFs reduce the tax revenue, as well as domestic resources, needed to fund programs for poverty reduction, together with providing the infrastructure for developing economies. Consequently, IFFs are receiving growing attention as an important development challenge.

- IFFs reduce much-needed resources. They also portray symptoms of deeper challenges, for example, reducing poverty and sharing in prosperity. Weak accountability and compromised transparency, coupled with vested interests, are contributing factors.

- Concerted actions and decisive international cooperation are required by both developing economies and developed nations, forming partnerships with civil society and the private sector.

- The World Bank Group can make vital contributions in addressing IFFs, owing to their convening power worldwide and vast technical knowledge. They are furthermore committed to this important task.

2.2. Features/Characteristics of IFFs

- Illicit in origin, transfer, or use. Value created illicitly (criminal activities), transferred illicitly (violation of currency controls), or used illicitly (terrorism financing).

- Exchange of value. This includes when of goods and services are exchanged, as well as financial and non-financial assets (illicit cross-border bartering).

- IFFs measure flow of value over a given time.

- Flows that cross a border (ownership changes between a country resident and non-resident).

2.3. Categories of IFFs

Commercial Activities

2.4. The Drivers of IFFs

2.5. Impact of IFFs

2.6. Curbing IFFs

2.7. Regulatory Environment

2.7.1. Accounting Principles and Standards

2.7.2. International Accounting Standards on Income Taxes (IAS 12)

2.7.3. King IV Corporate Governance Sections on Fraud and Corruption

2.7.4. Auditing Professions Act (APA) on Reportable Irregularities

- May likely result in material financial loss to an entity having partners, members, shareholders, creditor, or investors (stakeholders) associated with the entity; or

- Is fraudulent; or

- Amounts to theft; or

- Represents a material breach of any fiduciary duty (defined as a legal duty to act solely in another party’s interests). Such duty may be owned to the entity or its partners, members, shareholders, creditors, or investors (stakeholders) under any law applying to the entity, or conduct, or management thereof.

2.8. Other Initiatives Aimed at Curbing IFFs

2.8.1. The Financial Action Task Force

2.8.2. Global Financial Integrity (GFI)

2.8.3. Sustainable Development Goals Related to IFFs 16.4

2.9. Critical Reflection of Methods and Tools for Identifying and Managing Illict Financial Flows

2.10. The Conceptual Framework

3. Discussion and Validation

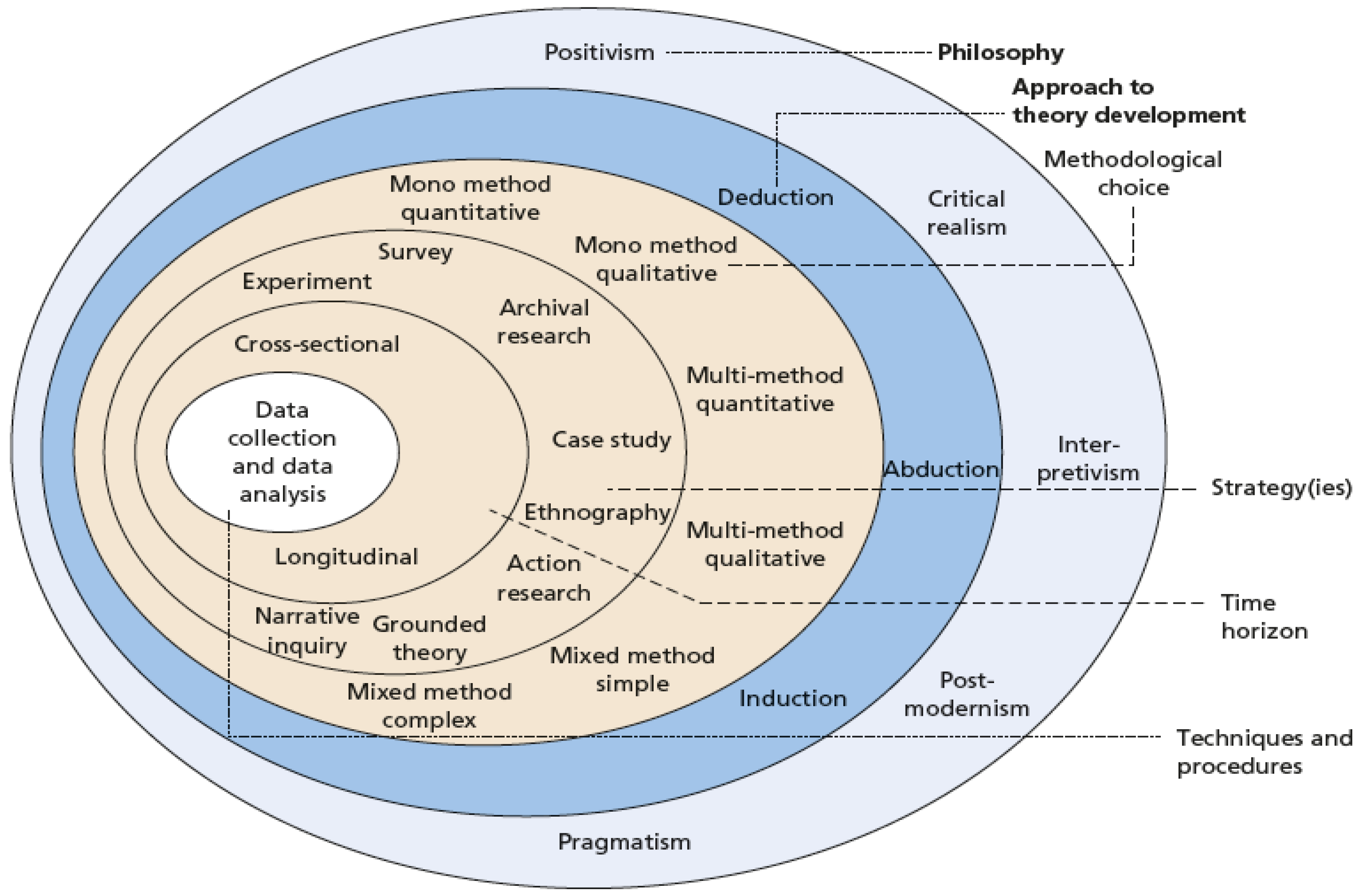

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullah, Zinatul Iffah Binti, Mahmoud Khalid Almsafir, and Ayman Abdal-Majeed Al-Smadi. 2015. Transparency and Reliability in Financial Statement: Do They Exist? Evidence from Malaysia. Open Journal of Accounting 4: 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abed, Ibtihal A., Nazimah Hussin, Mostafa A. Ali, Nada Salman Nikkeh, and Mohammed A. Mohammed. 2020a. Creative Accounting Phenomenon in the Financial Reporting: A Systematic Review Classification, Challenges. Technology Reports of Kansai University 62: 5977–88. [Google Scholar]

- Abed, Ibtihal A., Nazimah Hussin, and Mostafa A. Ali. 2020b. Piloting the Role of Corporate Governance and Creative Accounting in Financial Reporting Quality. Technology Reports of Kansai University 62: 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Abed, Ibtihal A., Nazimah Hussin, Hossam Haddad, Tareq Hammad Almubaydeen, and Mostafa A. Ali. 2022. Creative Accounting Determination and Financial Reporting Quality: The Integration of Transparency and Disclosure. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 8: 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, Fola. 2019. Illicit Financial Flows and Inequality in Africa: How to Reverse the Tide in Zimbabwe. South African Journal of International Affairs 26: 367–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiputra, I. Made Pradana, Sidharta Utama, and Hilda Rossieta. 2018. Transparency of Local Government in Indonesia. Asian Journal of Accounting Research 3: 123–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, Khushbu, and Chanchal Chatterjee. 2015. Earnings Management and Financial Distress: Evidence from India. Global Business Review 16 Suppl. 5: 140S–154S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayemi, Sunday Adebayoa, and Morohunfola Olasunkanmi Abdul-Lateef. 2017. Accounting Numbers and Management’s Financial Reporting Incentives: Evidence from Positive Accounting Theory. Noble International Journal of Economics and Financial Research 2: 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Anicic, Jugoslav, Dusan Anicic, and Aleksandar Majstorovic. 2017. Accounting and Financial Reports in the Function of Corporate Governance. Journal of Process Management. New Technologies 5: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auditing Professions Act (APA). 2005. Testimony of South African Government. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/auditing-profession-act (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Asongu, Simplice, and John Ssozi. 2016. Sino-African Relations: Some Solutions and Strategies to the Policy Syndromes. Journal of African Business 17: 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasa, Tiberias. 2018. Illicit Financial Flows in Kenya: Mapping of the Literature and Synthesis of the Evidence. Nairobi: Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR). Available online: https://www.africaportal.org/documents/18459/Kenya-Illicit-Financial-Flows-Report.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Bardhan, Indranil, Shu Lin, and Shu Ling Wu. 2015. The Quality of Internal Control over Financial Reporting in Family Firms. Accounting Horizons 29: 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassemir, Moritz, and Zoltán Novotny-farkas. 2018. IFRS Adoption, Reporting Incentives and Financial Reporting Quality in Private Firms. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 45: 759–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, Anne, Daniel A. Cohen, Thomas Z. Lys, and Beverly R. Walther. 2010. The Financial Reporting Environment: Review of the Recent Literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50: 296–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohoslavsky, Juan Pablo. 2018. Tax-Related Illicit Fi Nancial Fl Ows and Human Rights. Journal of Financial Crime 25: 750–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusca, Isabel, and Juan Martínez. 2016. Adopting International Public Sector Accounting Standards: A Challenge for Modernizing and Harmonizing Public Sector Accounting. International Review of Administrative Sciences 82: 761–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijze, Anoeska Wilhelmina Geertruida Johanna. 2013. The Principle of Transparency in EU Law. Utrecht: Utrecht University. [Google Scholar]

- Catzín-Tamayo, Abril, Oscar Frausto-Martínez, and Lucinda Arroyo-Arcos. 2022. Stakeholder Mapping and Promotion of Sustainable Development Goals in Local Management. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, Chanchal. 2020. Board Quality and Earnings Management: Evidence from India. Global Business Review 21: 1302–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowla, Peter, and Tatiana Falcao. 2016. Illicit Financial Flows: Concepts and Scope. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Illicit-financial-flows-conceptual-paper_FfDO-working-paper.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Cobham, Alex. 2018. Target 2030: Illicit Financial Flows. Globalization, Development and Governance. Available online: https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/analyses/target-2030-illicit-financial-flows/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Collin, Matthew. 2016. Illicit Financial Flows: Concepts, Measurement, and Evidence. The World Bank Research Observer 35: 44–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivelli, Ernesto, Ruud A. Mooij, and Michael Keen. 2015. Base Erosion, Profit Shifting and Developing Countries. IMF Working Papers 15: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, Goshu. 2020. Does IFRS Adoption Improve Financial Reporting Quality? Evidence from Commercial Banks of Ethiopia. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting 11: 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diantini, Ni Nyoman Ayu, Chloe C. Y. Ho, and Rui Zhong. 2022. Price-Fixing Agreements and Financial Reporting Opacity. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, By Alex, and Fredrik Eriksson. 2018. Improving Coherence in the Illicit Financial Flows Agenda. Available online: https://beta.u4.no/publications/improving-coherence-in-the-illicit-financial-flows-agenda.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Ezeagba, Charles, and Mary-Fidelis Abiahu. 2018. Influence of Professional Ethics and Standards in Less Developed Countries: An Assessment of Professional Accountants in Nigeria. Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting 6: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Action Task Force. 2020. Trade-Based Money Laundering Trends and Developments. Toronto: Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units. Available online: www.fatf-gafi.org (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Fisher, Timothy C. G., Ilanit Gavious, and Jocelyn Martel. 2019. Earnings Management in Chapter 11 Bankruptcy. Abacus 55: 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstater, Maya. 2016. Illicit Flows and Trade Misinvoicing: Are We Looking under the Wrong Lamppost? CMI Insights 5: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Forstater, Maya. 2018. Misinvoicing, and Multinational Tax Avoidance: The Same or CGD Policy Paper 123 March 2018. No. 123. CGD Policy Paper. Available online: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/illicit-financial-flows-trade-misinvoicing-and-multinational-tax-avoidance.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Foster, Benjamin, Guy McClain, and Trimbak Shastri. 2013. The Auditor’s Report on Internal Control & Fraud Detection Responsibility: A Comparison of French and U.S. Users’ Perceptions. Journal of Accounting, Ethics and Public Policy 14: 221–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fransesco, Thadeus, Quelmo Patty, and Paulus Libu Lamawitak. 2021. Positive And Normative Accounting Theory: Definition And Development. International Journal of Economics, Management, Business and Social Science (IJEMBIS) 1: 184–93. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Yi, Elizabeth Carson, and Roger Simnett. 2015. Transparency Report Disclosure by Australian Audit Firms and Opportunities for Research. Managerial Auditing Journal 30: 870–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geda, Alemayehu, and Addis Yimer. 2016. Capital Flight and Its Determinants: The Case of Ethiopia. African Development Review 28: 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, Omiros, Elisavet Mantzari, and Julia Mundy. 2021. Problematising the Decision-Usefulness of Fair Values: Empirical Evidence from UK Financial Analysts. Accounting and Business Research 51: 307–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Financial Integrity (GFI). 2021. Illicit Financial Flows in 134 Developing Countries: Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows. Available online: https://secureservercdn.net/50.62.198.97/34n.8bd.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/IFFs-Report-2021.pdf?time=1656257678 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Gumede, Vusi, and David Fadiran. 2019. Illicit Financial Flows in Southern Africa: Exploring Implications for Socio-Economic Development. Africa Development/Afrique et Développement 44: 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, Bernadette O., Innocent Makuta, Naor Bar-zeev, Levison Chiwaula, and Alex Cobham. 2015. The Effect of Illicit Financial Flows on Time to Reach the Fourth Millennium Development Goal in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Quantitative Analysis. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 107: 148–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, Paul M., and James Michael Wahlen. 2005. A Review of the Earnings Management Literature and Its Implications for Standard Setting. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, Niclas, Jordi Carenys, and Soledad Moya Gutierrez. 2018. Introducing More IFRS Principles of Disclosure—Will the Poor Disclosers Improve? Accounting in Europe 15: 242–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HLP. 2014. Illicit Financial Flows. High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, 1–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yeni, Bian Zhou, and Liya Liu. 2022. Regulatory Arbitrage, Bank Opacity and Risk Taking in Chinese Shadow Banking from the Perspective of Wealth Management Products. China Economic Quarterly International 2: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, John, and Alex Fisher. 2015. Five Steps to Simplifying Financial Statements—Today. Toronto: Chartered Professional Accountants Canada. Available online: https://logankatz.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Five_Steps_to_Simplifying_Financial_Statements.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Institute of Directors Southern Africa. 2016. Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa 2016. In King IV Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa. Sandton: Institute of Directors in Southern Africa. Available online: https://www.iodsa.co.za/page/DownloadKingIVapp (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Ismail, Suhaiza. 2022. Perception of the Malaysian Federal Government Accountants of the Usefulness of Financial Information under an Accrual Accounting System: A Preliminary Assessment. Meditari Accountancy Research. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahler, Miles, Maya Forstater, Michael G. Findley, Jodi Vittori, Erica Westenberg, and Yaya J. Fanusie. 2018. Global Governance to Combat Illicit Financial Flows. New York: Council on Foreign Relations, p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Kausar, Asad, and Clive Lennox. 2017. Balance Sheet Conservatism and Audit Reporting Conservatism. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 44: 897–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellenberg, Derek, and Arik Levinson. 2019. Misreporting Trade: Tariff Evasion, Corruption, and Auditing Standards. Review of International Economics 27: 106–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, Jagan, Jayanthi Krishnan, and Sophie Liang. 2020. Internal Control and Financial Reporting Quality of Small Firms. Review of Accounting and Finance 19: 221–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenard, Mary Jane, Karin A. Petruska, Pervaiz Alam, and Bing Yu. 2016. Internal Control Weaknesses and Evidence of Real Activities Manipulation. Advances in Accounting 33: 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, Clive, Chunfei Wang, and Xi Wu. 2020. Opening Up the ‘Black Box’ of Audit Firms: The Effects of Audit Partner Ownership on Audit Adjustments. Journal of Accounting Research 58: 1299–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, Baruch. 2018. The Deteriorating Usefulness of Financial Report Information and How to Reverse It The Deteriorating Usefulness of Fi Nancial Report Information and How to Reverse It. Accounting and Business Research 48: 465–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Wenbin, Gary Gang Tian, Jun Hu, and Daifei (Troy) Yao. 2020. Bearing an Imprint: CEOs’ Early-Life Experience of the Great Chinese Famine and Stock Price Crash Risk. International Review of Financial Analysis 70: 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, Nicholas J., Liz J. Campbell, and Karin Van Wingerde. 2019. Other People’s Dirty Money: Professional Intermediaries, Market Dynamics and the Finances of White-Collar, Corporate and Organized Crimes. British Journal of Criminology 59: 1217–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrueño, Rogelio, and Magdalene Silberberger. 2022. Dimensions and Cartography of Dirty Money in Developing Countries: Tripping Up on the Global Hydra. Politics and Governance 10: 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjoub, Imen, and Anthony Miloudi. 2015. Earnings Management: A Review of Literature. Paper presented at Euro and the European Banking System: Evolutions and Challenges, Iasi, Romania, June 4–6; pp. 691–703. [Google Scholar]

- Makhaiel, Nargis Kaisar Boles, and Michael Leslie Joseph Sherer. 2018. The Effect of Political-Economic Reform on the Quality of Financial Reporting in Egypt. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 16: 245–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, Mariola Jolanta. 2022. Trade-Based Money Laundering (TBML) Empowers Criminals to Run Free Post-Brexit. Journal of Money Laundering Control 25: 376–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, Bita, and Hamid Kalhornia. 2016. Relationship between Financial Reporting Transparency and Investment Efficiency: Evidence from Iran. International Journal of Economics and Management Engineering 10: 2433–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mohmed, Abobaker, Antoinette Flynn, and Colette Grey. 2020. The Link between CSR and Earnings Quality: Evidence from Egypt. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 10: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, Manuel F. 2020. The Role of South-South Cooperation in Combatting Illicit Financial Flows. Available online: https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TCPB11_The-Role-of-South-South-Cooperation-in-Combatting-Illicit-Financial-Flows_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Musselli, Irene, and Elisabeth Bürgi Bonanomi. 2020. Illicit Financial Flows: Concepts and Definition. pp. 1–26. Available online: https://curbing-iffs.org/2020/02/24/illicit-financial-flows-concepts-and-definition/ (accessed on 1 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Mutio, Philip. 2020. Illicit Financial Flows and the Extractives Sector on the African Continent: Impacts, Enabling Factors and Proposed Reform Measures. Academics Stand Against Poverty 1: 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Mwita, R. M., B. Chachage, Robert Galan Mashenene, and L. R. Msese. 2019. The Role of Financial Accounting Information Transparency in Combating Corruption in Tanzanian SACCOS. African Journal of Applied Research 5: 108–19. Available online: http://dspace.cbe.ac.tz:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/214 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Naheem, Mohammed Ahmad. 2015. Trade Based Money Laundering: Towards a Working Definition for the Banking Sector. Journal of Money Laundering Control 18: 513–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naheem, Mohammed Ahmad. 2020. The Agency Dilemma in Anti-Money Laundering Regulation. Journal of Money Laundering Control 23: 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, Shabrina Tri Asti, Rizqy Fadhlina Putri, Iskandar Muda, and Syafruddin Ginting. 2020. Positive Accounting Theory: Theoretical Perspectives on Accounting Policy Choice. Unicees 2018: 1128–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndikumana, Léonce, James Boyce, and Ameth Saloum Ndiaye. 2014. Capital Flight from Africa: Measurement and Drivers. In Capital Flight from AfricaCauses, Effects, and Policy Issues. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 14–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotoso, Matthew Olubayo, Daniël Petrus Schutte, and Merwe Oberholzer. 2022. The Effect of the Adoption of International Financial Reporting Standards on Foreign Portfolio Investment in Africa. South African Journal of Accounting Research 36: 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Bienvenido, Jesús Sanjuán, and Antonio Casquero. 2019. Illicit Financial Flows: Another Road Block to Human Development in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Social Indicators Research 142: 1231–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osasere, Aigienohuwa, and Ofuan Ilaboya. 2018. IFRS Adoption and Financial Reporting Quality: IASB Qualitative Characteristics Approach. Accounting and Taxation Review 2: 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowska, Marta. 2018. Transparency Regime within the Financial Institutions: Does It Really Work? In Governance and Regulations’ Contemporary Issues. Edited by Simon Grima and Pierpaolo Marano. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, vol. 99, pp. 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolone, Francesco, and Cosimo Magazzino. 2014. Earnings Manipulation among the Main Industrial Sectors. Evidence from Italy. Economia Aziendale Online 5: 253–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrot, Karen M. 2017. A Quantitative Study on the Difference between Us GAAP and IFRS Measuring Comparability with Financial Ratios. Ph.D. thesis, Northcentral University, Scottsdale, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, Aitor, and Iliana Olivié. 2015. Europe Beyond Aid: Illicit Financial Flows. Available online: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/Europe-Beyond-Aid-Illicit-Financial-Flows-background-paper.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Picciotto, S. 2018. Report of the Second Expert Meeting on the Statistical Measurement of Illicit Financial Flows—20–22 June 2018. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/stat2018_em_iff0620_report_en.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Pontoppidan, Caroline Aggestam, and Isabel Brusca. 2016. The First Steps towards Harmonizing Public Sector Accounting for European Union Member States: Strategies and Perspectives. Public Money & Management 36: 181–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, Novia, and Aza Azlina Md Kassim. 2020. Fraud Triangle Theory and Accounting Irregularities. Selangor Business Review 5: 55–64. Available online: http://sbr.journals.unisel.edu.my/ojs/index.php/sbr/article/view/39 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Reuter, Peter. 2017. Illicit Financial Flows and Governance: The Importance of Disaggregation. In World Development Report 2017 Governance and the Law. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/26210/112973-WP-PUBLIC-WDR17BPIllicitFinancialFlows.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Roy, Chinmoy. 2016. Financial Reporting Irregularities in Indian Public Sector Units: An Analysis of Current Practices. SSRN Electronic Journal 23: 139–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychowdhury, Sugata, Nemit Shroff, and Rodrigo S. Verdi. 2019. The Effects of Fi Nancial Reporting and Disclosure on Corporate Investment: A Review. Journal of Accounting and Economics 68: 101246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, Mahdi, Raed Ammar Ajel, and Grzegorz Zimon. 2022. The Relationship between Corporate Governance and Financial Reporting Transparency. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salewski, Marcus, and Henning Zülch. 2013. The Association between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Earnings Quality—Evidence from European Blue Chips. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Mark N. K., Philip Lewis, and Adrian Thornhill. 2019. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidthuber, Lisa, Dennis Hilgers, and Sebastian Hofmann. 2020. International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSASs): A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Financial Accountability and Management 38: 119–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekgoka, Chaka Patrick, Venkata Seshachala Sarma Yadavalli, and Olufemi Adetunji. 2022. Privacy-Preserving Data Mining of Cross-Border Financial Flows. Cogent Engineering 9: 2046680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signé, Landry, Mariama Sow, and Payce Madden. 2020. Illicit Financial Flows in Africa: Drivers, Destinations, and Policy Options. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/research/illicit-financial-flows-in-africa-drivers-destinations-and-policy-options/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Susanti, Merry, I. Cenik Ardana, Sufiyati, and Sofia Prima Dewi. 2021. The Impact of IFRS 16 (PSAK 73) Implementation on Key Financial Ratios: An Evidence from Indonesia. Paper presented at the Ninth International Conference on Entrepreneurship and Business Management (ICEBM 2020), Online, November 19, vol. 174, pp. 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swai, Janeth P., and Cosmas S. Mbogela. 2016. Accrual-Based versus Real Earnings Management; the Effect of Ownership Structure: Evidence from East Africa. ACRN Oxford Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives 5: 121–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tassadaq, Fizza, and Qaisar Ali Malik. 2015. Creative Accounting and Financial Reporting: Model Development and Empirical Testing. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 5: 544–51. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. 2017. Illicit Financial Flows (IIFs). Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialsector/brief/illicit-financial-flows-iffs (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Thiao, Abdou. 2021. The Effect of Illicit Financial Flows on Government Revenues in the West African Economic and Monetary Union Countries. Cogent Social Sciences 7: 1972558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International. 2017. Illicit Financial Flows. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/corruptionary/illicit-financial-flows (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- UNCTAD. 2020. Tackling Illicit Financial Flows for Sustainable Development in Africa. In Economic Development in Africa Report 2020. Geneva: United Nations. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/aldcafrica2020_en.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI). 2018. Drivers of Illicit Financial Flows. Turin: UNICRI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNODC, and UNCTAD. 2020. Conceptual Framework for the Statistical Measurement of Illicit Financial Flows. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/IFF/IFF_Conceptual_Framework_for_publication_FINAL_16Oct_print.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Wasan, Pratibha, and Kalyani Mulchandani. 2020. Corporate Governance Factors as Predictors of Earnings Management. Journal of General Management 45: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Michael R. 2013. Financial Fraud Prevention and Detection. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 978-1-118-61763-2. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, Kenneth, and Andrew Root. 2019. Policy Uncertainty and Earnings Management: International Evidence. Journal of Business Research 100: 255–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Rong (Irene). 2018. Transparency and Firm Innovation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 66: 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Proposition Number | Description |

|---|---|

| Content Propositions | |

| PROPOSITION PC1 | IFFs require strong international cooperation and concerted efforts to facilitate the curbing of IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC2 | The World Bank Group and EU have a critical role to play in combating IFFs and can assist to curb IFFs by ensuring a more transparent financial system. |

| PROPOSITION PC3 | Tax evasion is often a reason for illegal cross-border transfers. |

| PROPOSITION PC4 | Trade transactions may be used to disguise origins of proceeds from crime. |

| PROPOSITION PC5 | Aggressive tax avoidance is legal; however, it is viewed as an IFF. |

| PROPOSITION PC6 | Financial irregularities in the form of, amongst others, falsification of information, misrepresentations, or omissions create more room for IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC7 | When earnings management are employed to move funds across the border or evade tax, it might be viewed as IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC8 | High tax rates are viewed as a major driver of IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC9 | Resource-rich countries are often prone to IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC10 | Low institutional capabilities create a conducive environment for IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC11 | Political instability leads to IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC12 | Simplified financial reports, auditing, and transparency in financial statements may assist in addressing IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC13 | Improving on financial reporting transparency may assist in addressing the challenge of IFFs |

| PROPOSITION PC14 | Financial reporting transparency can provide stakeholders with useful information to make informed decisions and combat IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC15 | Compliance with IFRS, the IPSASs and GAAP will assist in curbing IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC16 | Accounting principles and standards ought to be put in place to curb IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC17 | Entities ought to adhere to rules and regulations, including guidelines on corporate governance principles, as per King IV, to address IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC18 | Auditing services are vital for stakeholders and to address IFFs. |

| PROPOSITION PC19 | Effective controls ought to be put in place to facilitate the curb of IFFs. |

| General Propositions | |

| PROPOSITION PG1 | IFFs hinder state resources, revenues, in particular, and weaken governance. |

| PROPOSITION PG2 | Through the GFI, Sustainable Development Goal 16.4.1, as related to IFFs, may facilitate the curbing of IFFs. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Netshisaulu, N.N.; Van der Poll, H.M.; Van der Poll, J.A. A Conceptual Framework to Analyse Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs). Risks 2022, 10, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10090172

Netshisaulu NN, Van der Poll HM, Van der Poll JA. A Conceptual Framework to Analyse Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs). Risks. 2022; 10(9):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10090172

Chicago/Turabian StyleNetshisaulu, Ndiimafhi Norah, Huibrecht Margaretha Van der Poll, and John Andrew Van der Poll. 2022. "A Conceptual Framework to Analyse Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs)" Risks 10, no. 9: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10090172

APA StyleNetshisaulu, N. N., Van der Poll, H. M., & Van der Poll, J. A. (2022). A Conceptual Framework to Analyse Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs). Risks, 10(9), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10090172