Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine whether FinTech companies believe that the growing dependence on regulation represents a potential risk for their development. In 2021, we conducted a survey among Latvian FinTech companies to ascertain their attitude toward regulatory scrutiny. We received 31 responses, representing a 33% response rate. The responses show that regulation is still one of the most pressing issues for FinTech companies, even though it is not necessarily regulation per se that causes concerns, but the lack of a regulatory framework that would be suitable for the special situation of the FinTech sector. However, regulation is now regarded as less problematic than it was in a previous survey in 2019, when respondents saw regulation as the most pressing issue. Moreover, the FinTech industry anticipates better support from the regulator, such as more realistic sandbox approaches and a willingness to consider new business models. According to the survey responses, the UK, Estonian, and Lithuanian regulators can serve as inspiration in this regard. Latvian FinTech companies expect regulators to be more flexible and open in their communication. This study is intended to advance regulatory reform by aiding the understanding of the requirements of fast-evolving FinTech companies.

1. Introduction

The growth of the FinTech industry has been associated with, amongst other things, less regulation than for traditional financial market players (Lochy 2020; Barroso and Laborda 2022; Murinde et al. 2022; Horn et al. 2020). However, the situation is changing. From a regulatory perspective, some of the FinTech solutions provide services that are similar to more traditional financial services, and traditional financial service providers integrate more FinTech solutions into their operations and/or acquire FinTech companies as one way to keep up with FinTech development (Murinde et al. 2022). As a consequence, FinTech companies and/or financial services based on FinTech solutions are facing increased regulatory requirements as well as possible fines and lawsuits for non-compliance. This means that FinTech companies can less and less claim to be different from traditional financial institutions in delivering products, and some FinTech companies are moving away from the “We are not financial institutions” mantra of the past (Deloitte 2018). However, the FinTech sector as such is difficult to regulate. FinTech covers a broad range of activities and business models, including, e.g., digital financial services, robo advice, support, crowdfunding, and data analytics (Oehler et al. 2018, 2021; Barroso and Laborda 2022; Ma and Liu 2017). Moreover, even though FinTech companies are often much smaller than traditional financial service providers, they would still have to comply with the same regulation. They may also operate in multiple jurisdictions (also from an early stage), in which case they will have to abide by the regulation specific to each area or nation.

In our previous study (Rupeika-Apoga and Wendt 2021), FinTech companies perceived the current state of regulation as the main barrier to FinTech development. They were not necessarily complaining about too stringent requirements or too many laws, but instead about a lack of regulation. Specifically, they were hesitant to launch new ventures in a state of high uncertainty about potential new legislation that might prohibit or limit their future activities. However, as a result of customer and business pressure and the need for financial system stability, regulators have worked towards reducing the ambiguity of industry regulations (Restoy 2021b; Roy 2021; Feyen et al. 2021; Zaidi and Rupeika-Apoga 2021).

The purpose of this study is to examine whether FinTech companies believe that the growing dependence on the regulatory environment represents a potential risk for their development. We explore the attitude of FinTech companies towards regulatory scrutiny, regulatory risks in the sense of potential restrictions on their operations and business segments, and the potential impact of regulation and enforcement on the profitability of their activities, e.g., due to costs associated with the implementation of and compliance with regulation. Besides exploring the status quo, we also explore potential changes in their views since our previous study.

In order to achieve the purpose of our study, we conducted an online survey among FinTech companies in 2021. The survey included 33 questions divided into four sections: general information, business model attributes, current challenges confronting FinTech companies with a focus on regulatory risks, and prospects for the FinTech sector’s development. We received 31 responses to the survey, representing a 33% response rate among the identified Latvian FinTech companies.

Our contribution to the academic literature as well as the public and political debate is twofold. First, we link the business and legal aspects of FinTech industry regulation, whereas academic research has frequently treated these aspects independently of each other. Second, we discuss how the regulator can support FinTech industry growth in Latvia based on the findings of our analysis. Regulators not only in Latvia but also in other countries might be interested in these recommendations, in particular in light of Fintech companies’ operations in multiple jurisdictions.

We find that while regulation is still important to FinTech companies, it is less pressing than it was in 2019. The availability of qualified employees and/or experienced managers as well as international expansion were the primary concerns of FinTech companies in 2021. This indicates that the main challenges for the FinTech industry are similar to those in the traditional financial industry (Kaur et al. 2021). Although Latvian FinTech companies do not perceive the regulatory environment to be more hostile or restrictive than regulation in the European Union, there are not enough encouraging initiatives. The FinTech industry anticipates better support from the regulator, such as a more realistic sandbox approach and a willingness to understand new business models. Latvian FinTech companies expect the regulators to be more flexible and open in their communication.

The structure of this paper is as follows. The following section, Section 2, focuses on the theoretical background. Section 3 describes the data and methodology. Section 4 presents FinTech companies’ responses to the survey with a focus on their own assessment of the regulatory environment and how it can be improved. The final section, Section 5, discusses whether FinTech companies believe that the regulatory environment poses a risk to their ability to develop, and then it concludes.

2. Developments in Regulation

FinTech has been in the spotlight for the last few decades. However, many of the challenges associated with FinTech development have to do with its emerging and developmental state. For example, there is a lack of consensus regarding the definition of even basic concepts and the regulatory framework. It is still not unambiguously clear which companies fall within the domain of FinTech and, therefore, should be regulated accordingly (e.g., Rupeika-Apoga and Wendt 2021). In this study, we use the definition of FinTech provided by the Bank of Latvia and the Financial and Capital Markets Commission (Bank of Latvia 2020; FCMC 2020): “FinTech is a company that develops and uses new and innovative technologies in the area of financial services. This leads to the development of new financial products and services or a significant improvement of the existing ones”.

There is an ongoing debate about whether the growth potential of FinTech could be partly an effect of looser regulation than that applied to incumbents such as commercial banks (Rupeika-Apoga et al. 2022). Financial institutions can be regulated in two ways: the entity-based approach and the activity-based approach (Restoy 2021b). The entity-based approach limits its perimeter to entities licensed, authorized, or registered to pursue certain financial services, while the activity-based approach imposes rules on everyone involved in a particular activity.

An extensive and detailed set of rules has been introduced to prevent or mitigate the risks arising from providing financial services. Traditional financial institutions, such as banks and insurance companies, have specific (entity-based) obligations, such as those related to prudential requirements, which do not apply to competitors who exclusively provide services in specific market segments such as payment services, wealth management, or credit underwriting (Restoy 2021a). Bank-specific regulation entails high compliance costs and can therefore put them at a competitive disadvantage (Restoy 2021a; Feyen et al. 2021). Banks are subject to prudential obligations, which include minimum capital and liquidity requirements and restrictions on large exposures. In addition, banks are also subject to regulation on, e.g., consumer protection, anti-money laundering (AML), or business activities that relate to the various services they offer, including deposit taking, loan underwriting, payment services, and asset management (Kaur et al. 2021).

A substantial part of FinTech development relates to financial services that are offered in a highly regulated domain. However, some FinTech companies enter the financial industry with little or no interaction with financial regulators. Some FinTech companies lack a compliance culture with regard to their prudential or consumer protection obligations when delivering financial services (Arner et al. 2015). Arner et al. (2015) argue, though, that FinTech companies founded by former financial professionals and located in global financial centers have a stronger compliance culture compared to newcomers with a technological background and located in newly emerging FinTech hubs (Arner et al. 2015).

At the same time, a substantial portion of FinTech companies provide financial services that are highly regulated and will have to comply eventually. Since the advent of FinTech companies, no general adjustments have been made to financial regulation to accommodate their activities as financial service providers (Restoy 2021b). So far, there is no specific legislative framework for FinTech companies, except for a FinTech license in Switzerland, the introduction of the category of digital banks in some jurisdictions, or the regulation of crowdfunding platforms (Ehrentraud et al. 2020). FinTech companies are generally regarded as being similar to traditional financial service providers and are subject to the law in accordance with the services provided (activity-based) and not by the type of company (entity-based). Most FinTech companies are financial companies that are licensed and regulated according to their business models. However, FinTech companies also include technology companies that provide financial services (Rupeika-Apoga and Thalassinos 2020; Horn et al. 2020). The regulation of FinTech companies does not always aim at controlling the specific risks they pose, but rather aims at increasing competition or expanding access to financial services by introducing (temporarily) lighter requirements (Restoy 2019). As T. Rabi Sankar noted, “It is virtually impossible for legislation to catch up with the fast mutating Fintech landscape, but in the interim, regulation must adapt so that the financial system absorbs digital innovation in a non-disruptive manner” (Roy 2021).

Regulators are already developing principles that should play a role in FinTech regulation. The increasing digitalization of financial services can exacerbate certain information and communication technology (ICT) and cyber risks (Oehler and Wendt 2018), as well as risks in relation to the operational resilience and business continuity of financial entities, especially considering their growing exposure to and dependency on regulated or unregulated third-party service providers (EBA et al. 2022). FinTech start-ups are characterized by problems that start-ups in other industries also face, such as limited risk management, a lack of liquidity and profitability, as well as problems and difficulties in determining their obligations, such as required licenses or capital.

Currently, cybersecurity and risk management in the FinTech sector are priorities for regulators in performing supervision, in particular when it comes to outsourcing and cloud computing technologies. Therefore, in 2021, the European Commission published a legislative proposal for a regulation on Digital Operational Resilience in the EU financial services sector (“DORA”). It is designed to consolidate and upgrade ICT risk requirements throughout the financial sector to ensure that all participants in the financial system are subject to a common set of standards to mitigate ICT risks for their operations (European Commission 2020a). The proposal also introduces an oversight framework for critical third-party providers, such as cloud service providers. Another area is the ongoing work in the EU on a unified regulation of markets in crypto-assets (MiCA), which, once developed, will replace the national framework for virtual assets (European Commission 2020b). MiCA is supposed to support innovation and fair competition by creating a framework for the issuance and provision of services related to crypto-assets. In addition, it aims at ensuring a high level of consumer and investor protection and market integrity in the crypto-asset markets, as well as at addressing financial stability and monetary policy risks that could arise from the wide use of crypto-assets and distributed ledger technology (DLT)-based solutions in financial markets (Deloitte 2022).

Regulators need to balance the innovation and efficiency gains brought by FinTech companies with the potential challenges for oversight, enforcement, and consumer protection. The authorities need to cooperate in order to effectively enter this new territory and achieve the necessary goals. At the national level, central banks and other financial sector regulators need to cooperate with industry regulators as well as competition and data protection authorities (Feyen et al. 2021).

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Sample

There is no official list of FinTech companies in Latvia. We used the definition of the Bank of Latvia and FCMC, which defines a “FinTech as a company that develops and uses new and innovative technologies in the area of financial services” (Bank of Latvia 2020; FCMC 2020), and started with the 56 companies identified for our 2019 survey (Rupeika-Apoga and Wendt 2021). For our 2021 survey, which is the focus of this study, we added FinTech companies listed in the Swedbank Latvian FinTech report 2020 (Swedbank 2020) and then re-checked whether these companies fell under our definition. Then, we added FinTech companies from other data sources: Latvijas Bankas intelligence (Bank of Latvia 2020) and the Latvian Startup association Startin.lv Inventio Growth database (Startin 2021). In addition, the list of FinTech companies was cross-checked against the Register of Enterprises of the Republic of Latvia to ensure that only FinTech companies incorporated in Latvia were considered. In 2021, we identified 93 companies that fulfilled our criteria for inclusion in this study.

The survey was conducted with the assistance of the Central Bank of Latvia via personal contact with the companies included in the sample. In addition, the authors used social networks such as LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook and personal, phone, and online communication with representatives of the FinTech companies. We conducted the online survey in the summer of 2021 and received 31 responses, which corresponds to a response rate of 33%, which is satisfactory for this type of survey (Hoque 2004; Rikhardsson et al. 2020).

3.2. Survey Design

The survey design is based on our previous survey (Rupeika-Apoga and Wendt 2021). However, due to the fast-evolving Fintech landscape (Roy 2021), the design of the survey has been adjusted accordingly. In order to present a coherent conceptualization of FinTech activities, taking into account the diversity of sectors and specialized business models, we applied the taxonomy and classification of FinTech provided by the World Economic Forum (2020). The classification includes thirteen discrete primary FinTech categories, which have been further sorted into two overarching groups: retail-facing and market-provisioning activities. Retail-facing activities provide financial products and services focused on consumers, households, and micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), and largely corresponds to business-to-customer (B2C) activities. It includes activities such as digital lending, digital capital raising, digital banking, digital payments, digital savings, WealthTech, digital asset exchange, digital custody, and InsurTech (World Economic Forum 2020). Market-provisioning activities provide or support the infrastructure or key functions of FinTech and/or of markets for digital financial services and largely correspond to business-to-business (B2B) activities. These activities include RegTech, digital identity, alternative credit, data analytics, and enterprise technology provisioning (World Economic Forum 2020). In addition to the taxonomy and classification of FinTech by the World Economic Forum, we have also offered an open response option for other FinTech activities.

In order to make our survey results comparable to the neighboring countries, we also used some questions from the FinTech Report Estonia 2021 (Laidroo et al. 2021). Our survey consisted of 33 questions, of which 25 were compulsory. The main sections of the survey are as follows:

- General information, such as company name, maturity of the company, number of employees, revenue, etc.

- Business model attributes, such as key activities, key resources, value proposition, customer channels and segments, and revenue streams.

- Current challenges confronting FinTech companies, with a focus on regulatory risks, using 7-point and 8-point Likert scales. In addition, open questions followed as to whether there were any other important aspects that participants would like to mention in this context.

- Prospects for the development of the FinTech sector: Specifically, this part of the survey asks how to improve the FinTech sector, which activities the respondents see as having the most growth potential, and which government initiatives would help improve FinTech prospects. In addition, there are open questions on local and European FinTech regulation, asking respondents to share the aspects of the regulations they would like to see changed. Collaboration with other market participants (banks, notaries, etc.) and government institutions are asked about in the final questions.

4. Results

4.1. Business Model and Activities

The main financial services provided by FinTech companies include digital lending, digital payments, and digital wallets. Among the respondents, 57% have a B2B model, 24% percent have a B2C model, and 16% have a business-to-business-to-customer (B2B2C) model, meaning that they provide services to companies and to those companies’ customers at the same time, and 3% use another model. The respondents provide services to clients in Latvia and around the world. Commissions from products or services represent their primary source of revenue (40% of the respondents), followed by license fees from product or software licensing (17% of the respondents). They typically concentrate on managing day-to-day operations and providing ongoing client support using IT support tools. Digital identification, data analysis, and RegTech are the primary auxiliary services the respondents offer. They believe that open banking (19 out of 31), digital lending (14 out of 31), and data analysis with instant payments have the greatest development potential (13 out of 31).

4.2. Regulation

We asked the survey participants to rate the severity of specific problems affecting their business on a scale from 1 (not pressing) to 7 (extremely pressing). As shown in Table 1, the results show that the availability of skilled staff or experienced managers, expansion to foreign markets, and expansion of the product portfolio are most pressing. Finding customers, the cost of production or labor, and regulation appear to be slightly less pressing. Competition, access to finance, building partnerships with established players, and product market fit seem a little less pressing.

Table 1.

Responses to the question of how pressing specific problems are; 1 = not pressing, 7 = extremely pressing.

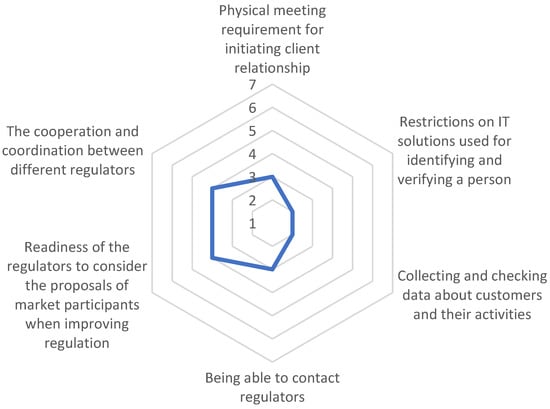

Figure 1 presents the regulative and regulator-related factors restricting FinTech companies’ expansion into markets outside of Latvia. The most critical issues are the readiness of the regulator to consider the market participants’ proposals for improvements to regulation, as well as cooperation and coordination between different regulators, with a score of 4 on a scale from 1 to 7.

Figure 1.

Regulative and regulator-related factors restricting the expansion into foreign markets on a scale from 1 (not pressing) to 7 (extremely pressing), medians.

The responses to the next survey question reflect the respondents’ opinion on the measures that might help develop their company and/or the Latvian FinTech sector further on a ranking scale from 1 (most important) to 8 (least important) (see Table 2). The respondents consider better cooperation with regulators, tax reliefs, and improvements to regulation as most helpful when it comes to advancing FinTech development. They also consider support for hiring a foreign workforce as important. Startup-visa, sandboxes, and specialized incubators appear helpful, but to a lower degree than the aspects mentioned above. Cooperation with educational and research institutions is considered the least helpful.

Table 2.

Answers to the question of what measures will help the further development of the respondent’s company and/or the Latvian FinTech sector.

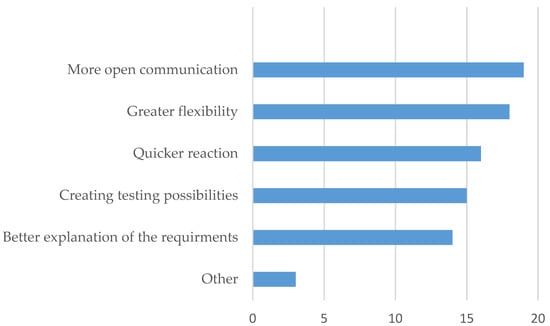

Figure 2 shows respondents’ perspectives on how regulators can help the industry adopt new FinTech solutions. More open communication and greater flexibility are considered as most relevant, followed by shorter response times, the creation of testing possibilities, and a better explanations of requirements.

Figure 2.

Relevance of regulators’ support in the implementation of new FinTech solutions, number of answers.

Furthermore, the participants responded to open questions about the regulation/requirements that should be changed in Latvia and Europe and how.

4.3. Future Development

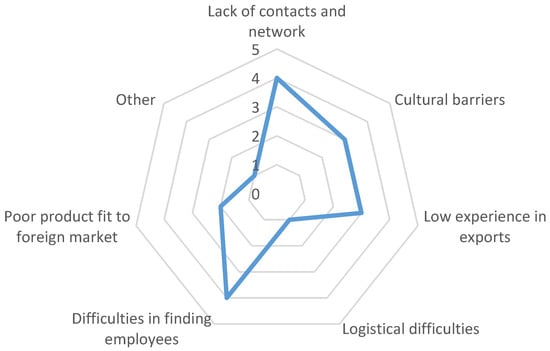

The participants were also asked to comment on factors other than regulation that limit their expansion abroad (Figure 3). Their responses show that both the lack of contacts and networks and the difficulty in finding employees are the most limiting factors for their expansion abroad.

Figure 3.

Factors restricting the expansion of FinTech companies into foreign markets (except regulation); 1 = not restrictive, 7 = extremely restrictive, medians.

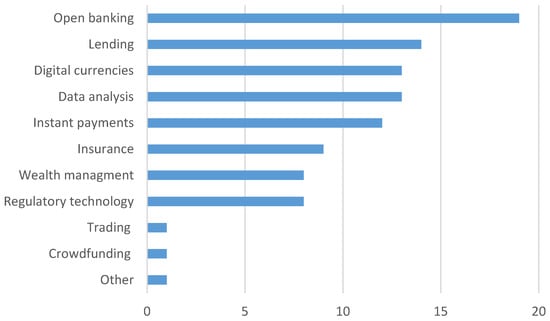

The respondents’ assessment of potential areas for development is presented in Figure 4. The respondents see the greatest potential for growth in open banking (19 out of 31 participants) as an area for development, followed by lending activities (14), digital currencies (13), data analysis (13) and instant payments (12). Insurance services (9), wealth management (8), and regulatory technology (8) are considered less relevant as areas for development, while trading and crowdfunding (each 1) do not appear to be relevant growth areas.

Figure 4.

Potential areas of FinTech development in the future, number of answers.

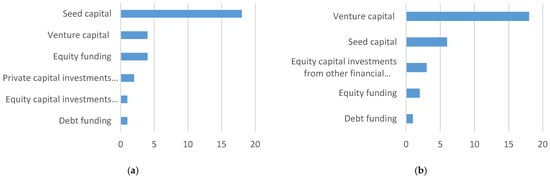

The results in Figure 5 show the respondents’ assessment of the importance of different funding options, sorted by their first choice (Figure 5a) and second choice (Figure 5b). Companies believe that over the next three years, seed capital will be the most important source of funding, followed by venture capital. Equity capital investments from other financial institutions, equity funding in general, and private capital investments from companies from other sectors are considered important funding options only by a few respondents. Debt funding is barely important at all.

Figure 5.

Answers to the question of what sources of funding companies consider the most important for the FinTech sector in the next three years: (a) First choice; (b) Second choice, number of responses.

As for cooperation with specialized organizations, the respondents cooperate mainly with the national regulator, the Financial and Capital Market Commission (26% of the respondents), the Latvian Startup Association (26%), and the Investment and Development Agency of Latvia (13%). At the same time, 26% of the respondents do not cooperate with specialized organizations at all.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Failure to comply with statutory or regulatory obligations and also regulatory uncertainty can pose legal risks for FinTech companies. As a result, increased regulation, a lack of support for innovative financial initiatives, or both, may contribute to business risk. Moreover, different levels of regulation for different types of entities, i.e., traditional financial service providers vs. FinTech companies, can hamper competition in financial markets (Oehler and Wendt 2018). This study explores whether Latvian FinTech companies believe that the regulatory environment poses risks to their business activities and their ability to develop further.

5.1. Emphasis on Regulation

There is no specific legislative framework in Latvia for FinTech companies. Depending on the financial services they offer, FinTech companies may be subject to regulation and supervision by the FCMC or the Consumer Protection Centre (CRPC). The FCMC is the primary authority regulating the financial markets. On the other hand, the CRPC guarantees consumer protection, market oversight, product and service safety, etc. FinTech companies must accordingly obtain licenses from the FCMC or the CRPC for any business activities that require licensing. Deposit-taking, investment management, the creation of financial instruments, payment or electronic money services, insurance, and consumer credit services are a few examples of activities that need licenses. There is no specific national framework in Latvia for obtaining authorization for crypto-asset transactions (Fintech Latvia 2022). The survey results revealed that Latvian regulators are not seen as the main supporters of the development of the industry. The Financial Conduct Authority in the UK and the Central Bank of Lithuania were mentioned by respondents as good examples.

Latvia, like many other countries, uses an activity-based approach to supervise and monitor the FinTech industry (Restoy 2021b). According to Crisanto et al. (2021), activity-based regulation can only supplement entity-based regulation rather than act as a replacement for it, because different types of institutions may create and be exposed to different risks when engaging in similar activity. In some cases, it is necessary to accept differences in the regulatory treatment of a particular activity if the corresponding risks depend on who performs the activities (“same activity, different risks, different regulation”). Financial stability risks, for example, differ depending on whether an entity is highly leveraged or capitalized, and whether loans are made by a deposit-taking institution, a closed-ended mutual fund, or a big technology company (Restoy 2021a). The results of our study support this notion; for example, RegTech regulation is considered as being less clear, and regulator clarification is required. One of the respondents proposed a less formal, risk-based, and more business-oriented approach to developing Latvia’s fintech industry, as well as clearly defined requirements, e.g., via handbooks or case studies, and technology standards that will ensure financial institution compliance with regulatory requirements.

According to the survey results, regulation is one of the top four most pressing issues for FinTech companies, but not the most pressing issue. This demonstrates that FinTech companies’ attitudes have shifted, as regulation was the most pressing issue in 2019 (Rupeika-Apoga and Wendt 2021). According to the results of the 2021 survey, the availability of skilled staff or experienced managers recently became the most pressing issue, while it ranked second in 2019. In addition, in the 2021 survey, finding customers is less of a pressing issue, while it ranked third in 2019. A survey of Estonian FinTech companies in 2021 revealed that the most critical problems are related to finding customers and regulation (Laidroo et al. 2021). Furthermore, regulation is less pressing for companies that provide supporting services than for those that provide financial services themselves. Regulation is also less pressing for companies involved in insurance and invoice financing than it is for those involved in crowdfunding and digital asset exchange. We can conclude that regulation is still an important issue for Latvian FinTech companies, but it is less pressing than it was previously. Potential explanations are complex. First, authorities’ attitudes have shifted, and FinTech companies are now regulated by major national financial regulators in the majority of countries. In many cases, regulation has been modified to accommodate FinTech companies (Rupeika-Apoga and Thalassinos 2020; Rupeika-Apoga et al. 2022). Second, anti-money-laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) regulations have evolved to protect FinTech companies, their customers, and the wider economy from financial crime. Third, as the regulatory environment becomes clearer, other issues that are common to all businesses become more visible.

5.2. Emphasis on Future Development

Regulators can not only restrict but also facilitate activities, because they can provide regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs to mitigate legal risks and support financial innovations (Rupeika-Apoga and Thalassinos 2020). Regulatory sandboxes give current and prospective participants in the financial market the chance to test and confirm that novel services adhere to regulatory requirements in accordance with the testing strategy approved by the regulator. They enable FinTech companies to test innovative financial products in the real world without having to go through the full authorization and licensing process. However, such sandbox approaches only apply for a limited time. Their goal is to clarify the legal framework’s applicability to new financial services and business models, as well as the regulatory framework in general. The UK, the USA, Australia, Switzerland, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates are a few of the nations that have already established regulatory sandboxes that allow for the temporary easing or updating of regulatory requirements (Rupeika-Apoga and Thalassinos 2020).

FinTech centers/hubs have been established by some regulators, including the United States, Singapore, Japan, Hong Kong, Australia, and Canada (Rupeika-Apoga and Thalassinos 2020). FinTech centers and hubs serve as points of contact for FinTech companies and other market participants. FinTech companies can get information about the FinTech industry and advice on how to make sure that innovative financial products, services, or business models adhere to licensing, supervision, and regulation.

The potential of sandboxes and incubators/hubs for FinTech development is highly valued by Latvian FinTech companies. The FCMC also provides a regulatory sandbox and an innovation hub for Fintech companies in Latvia. An electronic payment or electronic money service that is innovative or significantly improved at the national level could be tested in this sandbox. As the users of such an innovative service should clearly benefit from this service, the applicant should be able to demonstrate this contribution by concentrating primarily on the service users in Latvia, even though this does not preclude the possibility of also providing the service to other European Union (EU) member states (FCMC 2022). While the innovative hub provides qualified guidance in the area of cutting-edge technology, FinTech companies can get help with legislation, licensing, regulation, IT security, and AML provisions (Fintech Latvia 2021).

The survey results show that the Latvian authorities still have a lot to do to support financial innovation. According to the survey, the most significant obstacle to FinTech companies’ entry into international markets is regulators’ unwillingness to take market participants’ suggestions into account when modifying regulations. Cooperation and coordination among different regulators also need to be improved. However, other studies show that regulators in other countries are also slow to understand novel business models (e.g., Laidroo et al. 2021).

According to some of the respondents to our survey, the Latvian sandbox cannot be considered a full-fledged sandbox approach. Instead, it provides consultancy that almost always concludes that the FinTech company needs a license to provide a new service. In addition, if the service or product does not fall within one of the established service or product categories, and as such is difficult to understand within the established regulatory framework, the regulator tends to impose restrictions on the company’s operations instead of making an effort to assist in finding solutions that correspond to the new service. Some Latvian Fintech companies believe that regulators in other countries, such as the UK or Lithuania, are more accommodating than Latvian regulators. For instance, the UK’s sandbox allows businesses to test new business models while simultaneously learning more about them so that they can apply for a license once they are proven to be successful. In addition, being in the Lithuanian sandbox means that the FinTech company can run the service in a controlled environment within Lithuania, and the regulator provides fast-track license approval. On the positive side, with regard to supporting innovation, there is the option to partner with already-licensed institutions for Latvian solutions, but this comes at an additional cost. Furthermore, some companies stated that the CRPC is exceeding their capabilities in terms of customer solvency evaluation/scoring rules.

The market may benefit from innovation facilitators in many ways, but authorities may need to address potential risks. Consumers perceive being in a sandbox or incubator as a seal of quality or regulatory approval, according to Ehrentraud et al.’s (2020) review of consumer experiences. Informing consumers that the financial product or service they are buying is still being tested will thus be one of the authorities’ key challenges.

5.3. Concluding Remarks

Our study is not without limitations. First of all, even though our survey received a satisfactory response rate, the respondents still only represent a portion of Latvia’s FinTech industry. Second, the discussion and future research on the development of the FinTech industry would benefit from the inclusion of FinTech companies from other nations in order to provide better opportunities for international comparison and benchmarking. Third, our survey captures the participants’ views at one point in time only. Even though our comparison with our previous survey from 2019 and with other studies has allowed us to make some comparison over time, the fast evolvement of the FinTech sector calls for further analysis over time in order to keep up with the high levels of innovation and the corresponding responses and/or supporting activities of regulators.

Despite its limitations, our study provides an up-to-date assessment of the state of the development of the FinTech sector in Latvia and will hopefully help a broad range of stakeholders, including FinTech companies, regulators, traditional financial service providers, and business and private customers, to enhance their understanding of FinTech development in Latvia and to make corresponding decisions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R.-A. and S.W.; methodology, R.R.-A. and S.W.; formal analysis, R.R.-A. and S.W.; investigation, R.R.-A. and S.W.; data curation, R.R.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.-A. and S.W.; writing—review and editing, R.R.-A. and S.W.; visualization, R.R.-A. and S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Survey results are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the companies who took part in the survey. We are also grateful to Deniss Filipovs and Emīls Dārziņš (the Bank of Latvia) for their support in the survey’s implementation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arner, Douglas W., Janos Nathan Barberis, and Ross P. Buckley. 2015. The Evolution of Fintech: A New Post-Crisis Paradigm? SSRN Scholarly Paper 2676553. Rochester: Social Science Research Network. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bank of Latvia. 2020. FINTECH Glossary. Available online: https://www.bank.lv/en/publications-r/other-publications/fintech-glossary (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Barroso, Marta, and Juan Laborda. 2022. Digital Transformation and the Emergence of the Fintech Sector: Systematic Literature Review. Digital Business 2: 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisanto, Juan Carlos, Johannes Ehrentraud, and Marcos Fabian. 2021. Big Techs in Finance: Regulatory Approaches and Policy Options. FSI Briefs 12. BIS. Available online: https://www.bis.org/fsi/fsibriefs12.htm (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Deloitte. 2018. Fintechs and Regulatory Compliance: Understanding Risks and Rewards. WSJ. Available online: https://deloitte.wsj.com/cfo/2018/01/25/fintechs-and-regulatory-compliance-understanding-risks-and-rewards/ (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Deloitte. 2022. Digital Finance: European Parliament Adopts MiCA Regulation, Paving the Way for an Innovation-Friendly Crypto Regulation. Luxembourg: Deloitte. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/lu/en/pages/financial-services/articles/digital-finance-european-parliament-adopts-mica-regulation-innovation-friendly-crypto-regulation.html (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- EBA, EIOPA, and ESMA. 2022. Joint European Supervisory Authority Response to the European Commission’s February 2021 Call for Advice on Digital Finance and Related Issues: Regulation and Supervision of More Fragmented or Non-Integrated Value Chains, Platforms and Bundling of Various Financial Services, and Risks of Groups Combining Different Activities. Available online: https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/documents/files/document_library/Publications/Reports/2022/1026595/ESA%202022%2001%20ESA%20Final%20Report%20on%20Digital%20Finance.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Ehrentraud, Johannes, Denise Garcia Ocampo, Lorena Garzoni, and Mateo Piccolo. 2020. Policy Responses to Fintech: A Cross-Country Overview. Basel: Financial Stability Institute, BIS. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2020a. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Digital Operational Resilience for the Financial Sector and Amending Regulations (EC) No 1060/2009, (EU) No 648/2012, (EU) No 600/2014 and (EU) No 909/2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020PC0595 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- European Commission. 2020b. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Markets in Crypto-Assets, and Amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020PC0593 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- FCMC. 2020. FinTech Glossary. FKTK. Available online: https://www.fktk.lv/en/licensing/innovation-and-fintech/fintech-glossary/ (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- FCMC. 2022. Regulatory Sandbox. FKTK. Available online: https://www.fktk.lv/en/licensing/innovation-and-fintech/innovation-sandbox/ (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Feyen, Erik, Jon Frost, Leonardo Gambacorta, Harish Natarajan, and Matthew Saal. 2021. Fintech and the Digital Transformation of Financial Services: Implications for Market Structure and Public Policy. BIS and World Bank Group. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap117.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Fintech Latvia. 2021. Innovation Hub—Fintech Latvia. November 25. Available online: https://fintechlatvia.eu/innovation-hub/ (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Fintech Latvia. 2022. Requirements for Crypto-Asset Issuers and Service Providers. March 31. Available online: https://fintechlatvia.eu/crypto-asset/requirements-for-crypto-asset-issuers-and-service-providers/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Hoque, Zahirul. 2004. A Contingency Model of the Association between Strategy, Environmental Uncertainty and Performance Measurement: Impact on Organizational Performance. International Business Review 13: 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, Matthias, Andreas Oehler, and Stefan Wendt. 2020. FinTech for Consumers and Retail Investors: Opportunities and Risks of Digital Payment and Investment Services. In Ecological, Societal, and Technological Risks and the Financial Sector. Edited by Thomas Walker, Dieter Gramlich, Mohammad Bitar and Pedram Fardnia. Palgrave Studies in Sustainable Business in Association with Future Earth. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 309–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Balijinder, Sood Kiran, Simon Grima, and Ramona Rupeika-Apoga. 2021. Digital Banking in Northern India: The Risks on Customer Satisfaction. Risks 9: 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidroo, Laivi, Anneliis Tamre, Mari-Liis Kukk, Elina Tasa, and Mari Avarmaa. 2021. FinTech Report Estonia 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352381420_FinTech_Report_Estonia_2021?channel=doi&linkId=60c77a0b458515dcee8ec72e&showFulltext=true (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Lochy, Joris. 2020. Ecosystems—The Key to Success for All Future Financial Services Companies. Finextra Research. November 16. Available online: https://www.finextra.com/blogposting/19537/ecosystems---the-key-to-success-for-all-future-financial-services-companies (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Ma, Yue, and De Liu. 2017. Introduction to the Special Issue on Crowdfunding and FinTech. Financial Innovation 3: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murinde, Victor, Efthymios Rizopoulos, and Markos Zachariadis. 2022. The Impact of the FinTech Revolution on the Future of Banking: Opportunities and Risks. International Review of Financial Analysis 81: 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehler, Andreas, and Stefan Wendt. 2018. Trust and Financial Services: The Impact of Increasing Digitalisation and the Financial Crisis. In The Return of Trust? Institutions and the Public after the Icelandic Financial Crisis. Edited by Throstur Olaf Sigurjonsson, David L. Schwarzkopf and Murray Bryant. Bentley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehler, Andreas, Matthias Horn, and Stefan Wendt. 2018. Neue Geschäftsmodelle durch Digitalisierung? Eine Analyse aktueller Entwicklungen bei Finanzdienstleistungen. In Disruption und Transformation Management. Edited by Frank Keuper, Marc Schomann, Linda Isabell Sikora and Rimon Wassef. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, pp. 325–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehler, Andreas, Matthias Horn, and Stefan Wendt. 2021. Investor Characteristics and Their Impact on the Decision to Use a Robo-Advisor. Journal of Financial Services Research 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restoy, Fernando. 2019. Regulating Fintech: What Is Going on, and Where Are the Challenges? October 17. Available online: https://www.bis.org/speeches/sp191017a.htm (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Restoy, Fernando. 2021a. Fintech Regulation: How to Achieve a Level Playing Field. Basel: Financial Stability Institute, BIS. [Google Scholar]

- Restoy, Fernando. 2021b. Regulating Fintech: Is an Activity-Based Approach the Solution? June 16. Available online: https://www.bis.org/speeches/sp210616.htm (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Rikhardsson, Pall, Stefan Wendt, Auður Arna Arnardóttir, and Throstur Olaf Sigurjónsson. 2020. Is More Really Better? Performance Measure Variety and Environmental Uncertainty. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 70: 1446–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Anup. 2021. Fintech Regulations Must Be Based on Entity, Not Activity: RBI Dy Governor. Business Standard. June 16. Available online: https://www.business-standard.com/article/finance/fintech-regulation-must-be-entity-based-rbi-deputy-governor-rabi-sankar-121092800472_1.html (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Rupeika-Apoga, Ramona, and Eleftherios Thalassinos. 2020. Ideas for a Regulatory Definition of FinTech. International Journal of Economics and Business Administration VIII: 136–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rupeika-Apoga, Ramona, and Stefan Wendt. 2021. FinTech in Latvia: Status Quo, Current Developments, and Challenges Ahead. Risks 9: 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupeika-Apoga, Ramona, Kristine Petrovska, and Larisa Bule. 2022. The Effect of Digital Orientation and Digital Capability on Digital Transformation of SMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 17: 669–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startin. 2021. Latvian Startup Database. Latvian Startup Association Startin.LV. Available online: https://startin.lv/startup-database/ (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Swedbank. 2020. Latvian Fintech Report 2020. Available online: https://www.swedbank.lv/static/pdf/campaign/FinTech_report_2020_ENG.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- World Economic Forum. 2020. Global COVID-19 FinTech Market Rapid Assessment Study. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/63338c21-4a48-4f1b-92d8-8af1d1289c0a/ (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Zaidi, Syeda Hina, and Ramona Rupeika-Apoga. 2021. Liquidity Synchronization, Its Determinants and Outcomes under Economic Growth Volatility: Evidence from Emerging Asian Economies. Risks 9: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).