Cryptocurrency as an Investment: The Malaysian Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Hypotheses Development

2.2. Independent Variables

2.2.1. Perceived Risk

2.2.2. Perceived Value

2.2.3. Control Variable

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurement of Variables

4. Results of Analysis on Investor’s Investment Profile

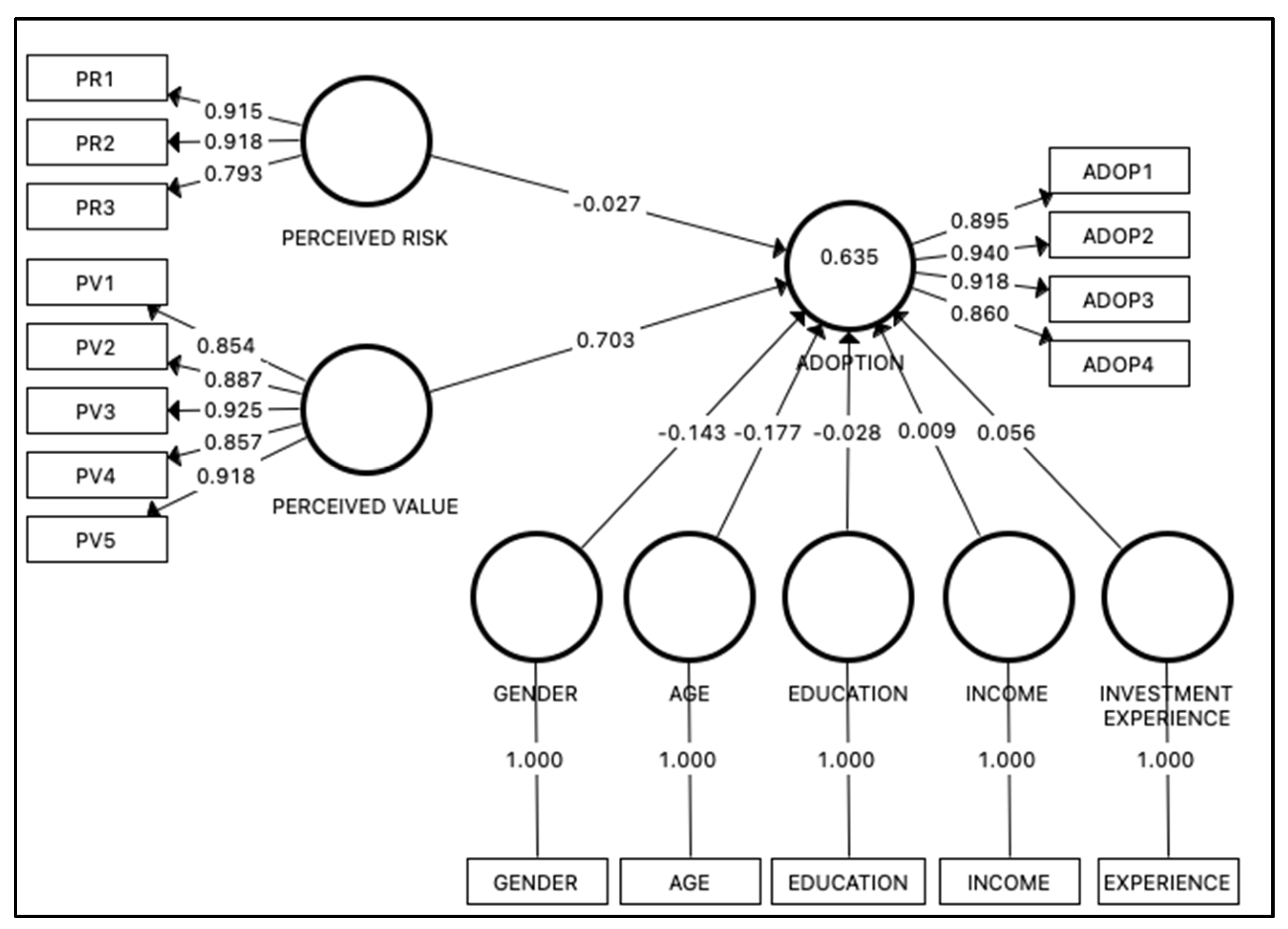

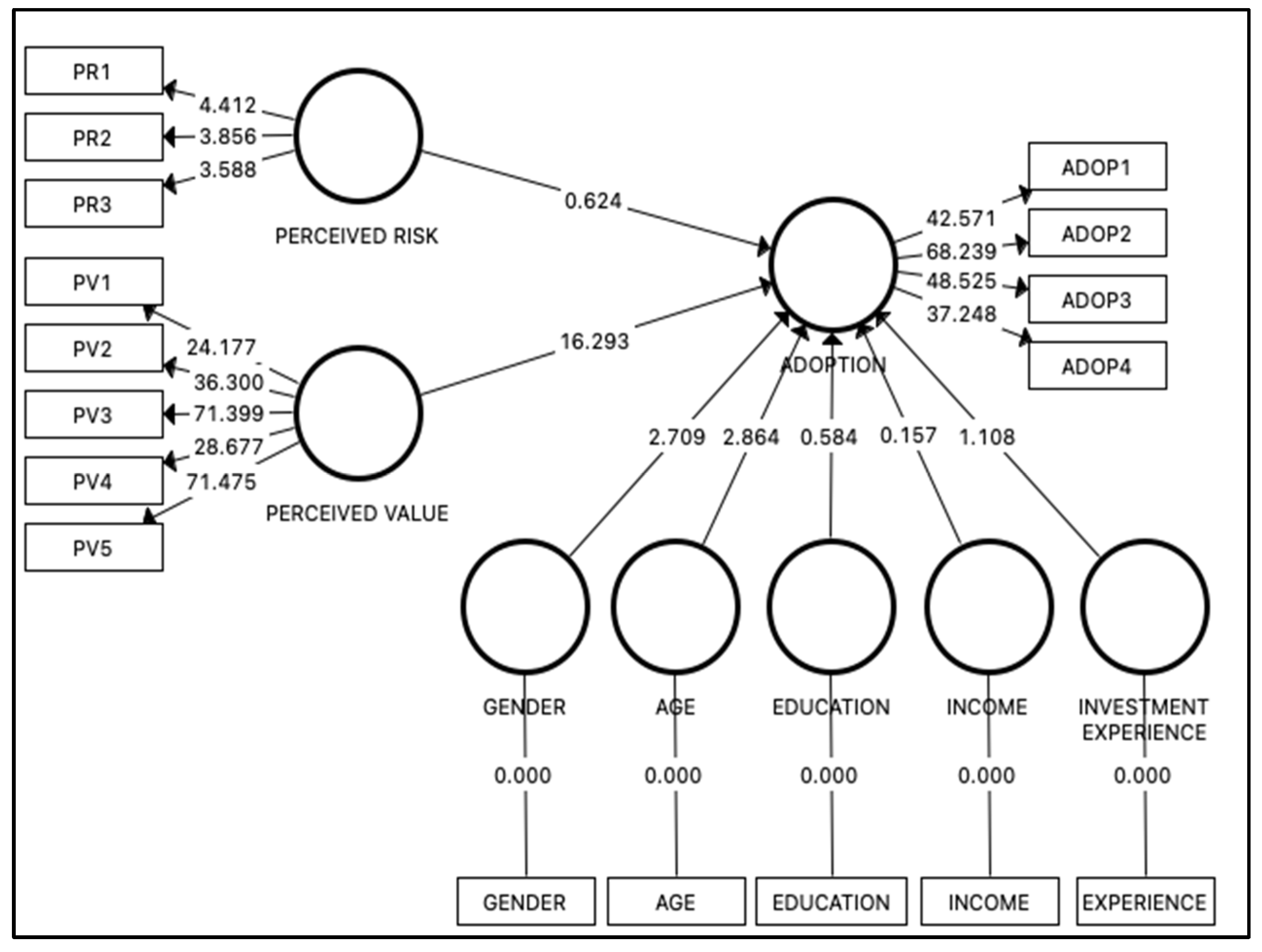

4.1. Structural Equation Modelling

4.2. Validity and Reliability Test

5. Implications and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Recommendations

5.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abramova, Svetlana, and Rainer Böhme. 2016. Perceived benefit and risk as multidimensional determinants of bitcoin use: A quantitative exploratory study. Paper present at the Thirty Seventh International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), Dublin, Ireland, December 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- AFM. 2018. Investing in Cryptos in the Netherlands. Amsterdam: AFM. [Google Scholar]

- Alalwan, Ali Abdallah, Abdullah Mohammed Baabdullah, Nripendra P. Rana, Kuttimani Tamilmani, and Yogesh Kumar Dwivedi. 2018. Examining adoption of mobile internet in Saudi Arabia: Extending TAM with perceived enjoyment, innovativeness and trust. Technology in Society 55: 100–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Oliva, Mario, Jorge Pelegrín-Borondo, and Gustavo Matias-Clavero. 2019. Variables influencing cryptocurrency use: A technology acceptance model in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baabdullah, Abdullah Mohammed. 2018. Consumer adoption of mobile social network games (M-SNGs) in Saudi Arabia: The role of social influence, hedonic motivation and trust. Technology in Society 53: 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, Amit, Sanjog Misra, and H. Raghav Rao. 2000. Online Risk, Convenience, and Internet Shopping Behavior. Communications of the ACM 43: 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Bernard S. 1992. Agents Watching Agents: The Promise of Institutional Investor Voice. UCLA Law Review 39: 811. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, Rainer, Nicolas Christin, Benjamin Edelman, and Tyler Moore. 2015. Bitcoin: Economics, technology, and governance. Journal Economic of Perspectives 29: 213–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Briere, Marie, Kim Oosterlinck, and Ariane Szafarz. 2015. Virtual Currency, Tangible Return: Portfolio Diversification with Bitcoin. Journal of Law, Technology and the Internet 7: 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, Eng-Tuck, and John Fry. 2015. Speculative bubbles in Bitcoin markets? An empirical investigation into the fundamental value of Bitcoin. Economics Letters 130: 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conchar, Margy P., George M. Zinkhan, Cara Peters, and Sergio Olavarrieta. 2004. An Integrated Framework for the Conceptualization of Consumers’ Perceived Risk Processing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 32: 373–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, Ann. 2014. Bitcoin and Illegal Activity: Silk Road Defendants Pled Guilty on September 4, 2014, UIC. The John Marshall Journal of Information Privacy & Technology Law. Available online: https://ripl.law.uic.edu/news-stories/bitcoin-and-illegal-activity-silk-road-defendants-pled-guilty-on-september-4-2014/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Durgha, Moorthy. 2018. A Study on Rising Effects of Cryptocurrency in the Regulations of Malaysian Legal System. International Journal of Business, Economics and Law 15: 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Faqih, Khaled M. S. 2016. An empirical analysis of factors predicting the behavioral intention to adopt Internet shopping technology among non-shoppers in a developing country context: Does gender matter? Journal Retailing Consumer Services 30: 140–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietkiewicz, Kaja, Elmar Lins, Katsiaryna. S. Baran, and Wolfgang G. Stock. 2016. Inter-generational comparison of social media use: Investigating the online behavior of different 151 generational cohorts. Paper present at 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, January 5–8; pp. 3829–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbott, Mark. 2008. Consumer Behaviour. In The Marketing Book. Edited by Michael J. Baker and Susan Hart. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 109–20. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Florian, Kai Zimmerman, Martin Haferkorn, Moritz Christian Weber, and Michael Siering. 2014. Bitcoin—Asset or Currency? Revealing Users’ Hidden Intentions. Social Science Research Network. Paper present at ECIS 2014 Proceedings-22nd European Conference on Information Systems, Tel Aviv, Israel, June 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Global Legal Research Center. 2018. Regulation of Cryptocurrency around the World. The Law Library of Congress 5080 June. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/law/help/cryptocurrency/regulation-of-cryptocurrency.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Grable, John E. 2000. Financial risk tolerance and additional factors that affect risk taking in everyday money matters. Journal of Business and Psychology 14: 625–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratt, Lawrence B. 1987. Risk Analysis or Risk Assessment: A Proposal for Consistent Definitions. In Uncertainty in Risk Assessment, Risk Management and Decision Making. Edited by V. T. Covello, L.B. Lave, A. Moghissi and V. R. R. Uppuluri. Advances in Risk Analysis. Boston: Springer, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Swati, Sanjay Gupta, Manjo Mathew, and Hanumantha Rao Sama. 2020. Prioritizing intentions behind investment in cryptocurrency: A fuzzy analytical framework. Journal of Economic Studies 48: 1442–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Chin-Lung, and Judy Chuan-Chuan Lin. 2015. What drives purchase intention for paid mobile apps?—An expectation confirmation model with perceived value. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 14: 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Weilun. 2019. The impact on people’s holding intention of bitcoin by their perceived risk and value. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja 32: 3570–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Yunyoung, Seongmin Jeon, and Byungjoon Yoo. 2015. Is Bitcoin a viable e-business? Empirical analysis of the digital currency’s speculative nature. Paper present at the ICIS 2015 Proceedings of 36th International Conference on Information Systems, Fort Worth, TX, USA, December 13–16; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Inci, A. Can, and Rachel Lagasse. 2019. Cryptocurrencies: Applications and investment opportunities. Journal of Capital Markets Studies 3: 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, Sirrka L., and Peter A. Todd. 1996–1997. Consumer Reactions to Electronic Shopping on the World Wide Web. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 1: 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Dekui, Ruihai Li, Shibo Bian, and Christopher Gan. 2021. Financial planning ability, risk perception and household portfolio choice. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 57: 2153–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannungo, Shivraj, and Vikas Jain. 2004. Relationship between risk and intention to purchase in an online context: Role of gender and product category. Paper present at the 13th European Conference on Information Systems, The European IS Profession in the Global Networking Environment, Turku, Finland, June 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ku-Mahamud, Ku Ruhana, Nur Azzah, Abu Bakar, and Mazni Omar. 2018. Blockchain, cryptocurrency and Fintech market growth in Malaysia. Journal of Advanced Research in Dynamical and Control Systems 10: 2074–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, David Kuo Chuen, Li Guo, and Yu Wang. 2018. Cryptocurrency: A new investment opportunity? Journal of Alternative Investments 20: 16–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Won Jun, Seong Tae Hong, and Taeki Min. 2019. Bitcoin distribution in the age of digital transformation: Dual-path approach. Journal of Distribution Science 16: 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Li, Jing Jian Xiao, Weiqiang Zhang, and Congyi Zhou. 2017. Financial literacy and risky asset holdings: Evidence from China. Accounting and Finance 57: 1383–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Kang Li. 2013. Investment Intentions: A Consumer Behaviour Framework. Crawley: UWA Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Mahomed, Nadim. 2017. Understanding Consumer Adoption of Cryptocurrencies. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Tello, Julio, Higinio Mora, Pujol Franscisco, and Miltiadis Lytras. 2018. Social commerce as a driver to enhance trust and intention to use cryptocurrencies for electronic payments. IEEE Access 6: 50737–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawang, Nazli Ismail, and Ida Madieha Abd Ghani Azmi. 2021. Cryptocurrency: An Insight into the Malaysian Regulatory Approach. Psychology and Education Journal 58: 1645–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nurbarani, Bella Siti, and Gatot Soepriyanto. 2022. Determinants of Investment Decision in Cryptocurrency: Evidence from Indonesian Investors. Universal Journal of Accounting and Finance 10: 254–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Yanli, Shan Wang, Jing Fan, and Min Zhang. 2015. An empirical study on the impact of perceived benefit, risk and trust on e-payment adoption: Comparing quick pay and union pay in China. Paper present at the 2015 7th International Conference on Intelligent Human-Machine Systems and Cybernetics, Hangzhou, China, August 26–27; vol. 2, pp. 198–202. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, J. Paul, and Jerry C. Olson. 1993. Consumer Behavior and Marketing Strategy, 3rd ed. Chicago: American Marketing Association. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, J. Paul, and Lawrence X. Tarpey Sr. 1975. A Comparative Analysis of Three Consumer Decision Strategies. Journal of Consumer Research 2: 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Thanh-Thao T., and Jonathn C. Ho. 2015. The effects of product-related, personal-related factors and attractiveness of alternatives on consumer adoption of NFC-based mobile payments. Technology in Society 43: 159–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polasik, Michal, Anna Iwona Piotrowska, Tornasz Piotr Wisniewski, Radoslaw Kotkowski, and Geoffrey Lightfoot. 2015. Price fluctuations and the use of bitcoin: An empirical inquiry. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 20: 9–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rufino, Cesar C. 2019. An analysis of the risk-return profile of the daily Bitcoin prices using different variants of the GARCH Model. Paper present at the 2019 DLSU Research Congress Manila, Manila, Philippines, July 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, Hyun-Sun, and Kwang Sun Ko. 2019. Understanding speculative investment behavior in the Bitcoin context from a dual-systems perspective. Journal of Industrial Management & Data Systems 119: 1431–56. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, Fakhar, GuoYi Xiu, Jian Wang, and Muhammad Shahbaz. 2018. An empirical investigation on the adoption of cryptocurrencies among the people of mainland China. Technology in Society 55: 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Mingxing, Jing Fan, and Yafang Li. 2014. An empirical study on consumer acceptance of mobile payment based on the perceived risk and trust. Paper present at the 2014 International Conference on Cyber-Enabled Distributed Computing and Knowledge Discovery, Shanghai, China, October 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, Soyeon, Mary Ann Eastlick, Sherry L. Lotz, and Patricia Warrington. 2001. An online prepurchase intention model: The role of intention to search: Best Overall Paper Award. Journal Retailing 77: 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, Narasimhan, and Brian T. Ratchford. 1991. An Empirical Test of a Model of Extended Search for Automobiles. Journal of Consumer Research 18: 233–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, James W. 1974. The Role of Risk in Consumer Behaviour. A comprehensive and operational theory of risk taking in consumer behavior. Journal of Marketing 38: 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayasarathy, Leo R., and Joseph M. Jones. 2000. Print and Internet Catalog Shopping. Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy 10: 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Elke U., and Richard A. Milliman. 1997. Perceived Risk Attitudes: Relating Risk Perception to Risky Choice. Management Science 43: 123–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Dingli, Timothy Ian O’Brien, and Elnaz Irannezhad. 2020. Investigating the investment behaviors in cryptocurrency. Journal of Alternative Investments 23: 141–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Heetae, Jieun Yu, Hangjung Zo, and Munkee Choi. 2016. User acceptance of wearable devices: An extended perspective of perceived value. Telematics and Informatics 33: 256–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeong, Yoon Chow, Khairul Shafee Kalid, and Savita K. Sugathan. 2019. Cryptocurrency acceptance: A case of Malaysia. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology 8: 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, Hayati, Mai Farhana Mior Badrul Munir, Zulnurhaini Zolkaply, Chin Li Jing, Chooi Yu Hao, Ding Swee Ying, Lee Seang Zheng, Ling Yuh Seng, and Tan Kok Leong. 2018. Behavioral Intention to Adopt Blockchain Technology: Viewpoint of the Banking Institutions in Malaysia. International Journal of Advanced Scientific Research and Management 3: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zahudi, Zalina Muhamed, and Radin Ariff Taquiddin Radin Amir. 2016. Regulation of Virtual Currencies: Mitigating the Risks and Challenges Involved. Journal of Islamic Finance 5: 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeithaml, Valarie A. 1988. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing 52: 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Haidong, and Lini Zhang. 2021. Financial literacy or investment experience: Which is more influential in cryptocurrency investment? International Journal of Bank Marketing 39: 1208–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmudzinski, Adrian. 2019. Malaysian Cryptocurrency Regulation to Classify Digital Assets, Tokens as Securities. Available online: https://cointelegraph.com/ (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Zulhuda, Sonny, and Afifah binti Sayuti. 2017. Whither Policing Cryptocurrency in Malaysia? IIUM Law Journal 25: 179–96. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Questions | Source |

|---|---|---|

| ADOP1 | How likely are you to invest in cryptocurrency this year? | Mahomed (2017), Faqih (2016), Shim et al. (2001), Gupta et al. (2020) |

| ADOP2 | I have plans to invest in cryptocurrencies in the future | |

| ADOP3 | There is a high probability I will invest in cryptocurrency next time | |

| ADOP4 | I will encourage others to invest in cryptocurrencies | |

| PR1 | Investing in cryptocurrencies is risky | |

| PR2 | There is too much uncertainty associated with investing in cryptocurrencies | |

| PR3 | Compared with other currencies/investments, cryptocurrencies are riskier | |

| PV1 | Using cryptocurrency in trading helps me improve the effectiveness, profitability, and investment of my money | |

| PV2 | I find that trading in cryptocurrencies can save money as it allows me to invest it quickly and inexpensively with lower transaction costs | |

| PV3 | Using cryptocurrency helps me improve my financial performance because I have total control over my money | |

| PV4 | I feel satisfied with my cryptocurrency investment decisions | |

| PV5 | Investing in cryptocurrencies will increase opportunities to achieve important goals for me |

| Characteristics | Respondent’s Profile (Retail Investors) | Total No. of Respondents: 211 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 157 | 74.4% |

| Female | 54 | 25.6% | |

| Age | 18–24 | 44 | 20.9% |

| 25–34 | 66 | 31.3% | |

| 35–44 | 38 | 18.0% | |

| 45–54 | 33 | 15.6% | |

| 55+ | 30 | 14.2% | |

| Education Level | Bachelor’s degree | 91 | 43.1% |

| Diploma | 45 | 21.3% | |

| Master’s degree | 37 | 17.5% | |

| High school | 15 | 7.1% | |

| Doctoral degree | 10 | 4.7% | |

| Professional degree | 10 | 4.7% | |

| No formal education | 3 | 1.4% | |

| Income | Below RM2000 | 43 | 20.4% |

| RM2001–RM4000 | 47 | 22.3% | |

| RM4001–RM6000 | 43 | 20.4% | |

| RM6001–RM8000 | 21 | 10.0% | |

| RM8001–RM10,000 | 22 | 10.4% | |

| Above RM10,000 | 35 | 16.6% | |

| Employment | Private sector | 100 | 47.4% |

| Self employed | 42 | 19.9% | |

| Student | 26 | 12.3% | |

| Government servant | 20 | 9.5% | |

| Retired | 13 | 6.2% | |

| Others | 10 | 4.7% | |

| Investment Experience | More than 3 years | 80 | 37.9% |

| 1–3 years | 73 | 34.6% | |

| Less than 1 year | 58 | 27.5% | |

| Investor’s Investment Portfolio | No. of Respondents | % |

|---|---|---|

| Years of Investment Experience | ||

| I have never invested in cryptocurrencies | 66 | 31.28% |

| Less than a year | 65 | 30.80% |

| From 1 to 2 years | 33 | 15.64% |

| More than 3 years | 28 | 13.27% |

| From 2 to 3 years | 19 | 9.00% |

| Portfolio Allocation | ||

| 0–20% | 108 | 51.18% |

| 21–40% | 59 | 27.96% |

| 41–60% | 26 | 12.32% |

| 81–100% | 9 | 4.27% |

| 61–80% | 9 | 4.27% |

| Depth in Knowledge of Cryptocurrency | ||

| A moderate amount | 95 | 45.02% |

| A little | 60 | 28.44% |

| None at all | 29 | 13.74% |

| A lot | 18 | 8.53% |

| A great deal | 9 | 4.27% |

| Cryptocurrency Investment | ||

| I have never invested in cryptocurrency | 66 | 31.28% |

| Invested in various cryptocurrency | 145 | 68.72% |

| Bitcoin | 97 | 45.97% |

| Ethereum | 75 | 35.55% |

| Litecoin | 36 | 17.06% |

| Tether | 36 | 17.06% |

| XRP | 79 | 37.44% |

| Uniswap | 11 | 5.21% |

| Others | 50 | 23.70% |

| Binance | 49 | 23.22% |

| Polkadot | 22 | 10.43% |

| Dogecoin | 43 | 20.38% |

| Construct | Items | Outer Loading | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Discriminant Validity | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adoption | ADOP1 | 0.895 | 0.947 | 0.817 | Established | N/A |

| ADOP2 | 0.94 | |||||

| ADOP3 | 0.918 | |||||

| ADOP4 | 0.86 | |||||

| Perceived Risk | PR1 | 0.915 | 0.909 | 0.769 | Established | 1.04 |

| PR2 | 0.918 | |||||

| PR3 | 0.793 | |||||

| Perceived Value | PV1 | 0.854 | 0.949 | 0.79 | Established | 1.21 |

| PV2 | 0.887 | |||||

| PV3 | 0.925 | |||||

| PV4 | 0.857 | |||||

| PV5 | 0.918 | |||||

| Gender | GENDER | 1 | 1 | 1 | Established | 1.20 |

| Age | AGE | 1 | 1 | 1 | Established | 1.57 |

| Education | EDUCATION | 1 | 1 | 1 | Established | 1.30 |

| Income | INCOME | 1 | 1 | 1 | Established | 1.50 |

| Investment Experince | EXPERIENCE | 1 | 1 | 1 | Established | 1.32 |

| Hypotheses | Relationships | t-Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PERCEIVED RISK -> ADOPTION | 0.624 | 0.532 | Not supported |

| H2 | PERCEIVED VALUE -> ADOPTION | 16.293 | 0 | Supported |

| Control Variables | ||||

| GENDER | 2.709 | 0.007 | Significant | |

| AGE | 2.864 | 0.004 | Significant | |

| EDUCATION | 0.584 | 0.559 | Not Significant | |

| INCOME | 0.157 | 0.876 | Not Significant | |

| INVESTMENT EXPERIENCE | 1.108 | 0.268 | Not Significant | |

| RELATIONSHIP | F2 | R2 | Q2 | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERCEIVED RISK -> ADOPTION | 0.002 | 0.635 | 0.488 | 0.044 |

| PERCEIVED VALUE -> ADOPTION | 1.116 | |||

| GENDER -> ADOPTION | 0.047 | |||

| AGE -> ADOPTION | 0.055 | |||

| EDUCATION -> ADOPTION | 0.002 | |||

| INCOME -> ADOPTION | 0 | |||

| INVESTMENT EXPERIENCE -> ADOPTION | 0.006 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sukumaran, S.; Bee, T.S.; Wasiuzzaman, S. Cryptocurrency as an Investment: The Malaysian Context. Risks 2022, 10, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10040086

Sukumaran S, Bee TS, Wasiuzzaman S. Cryptocurrency as an Investment: The Malaysian Context. Risks. 2022; 10(4):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10040086

Chicago/Turabian StyleSukumaran, Shangeetha, Thai Siew Bee, and Shaista Wasiuzzaman. 2022. "Cryptocurrency as an Investment: The Malaysian Context" Risks 10, no. 4: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10040086

APA StyleSukumaran, S., Bee, T. S., & Wasiuzzaman, S. (2022). Cryptocurrency as an Investment: The Malaysian Context. Risks, 10(4), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10040086