Investigation of Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge of Evidence-Based Clinical Practices for Preterm Neonatal Skin Care—A Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Procedure of Recruitment

2.3. Research Instrument

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographic and Occupational Characteristics

3.2. Participants’ Theoretical Knowledge about Neonatal Vernix Caseosa, Skin Microbiota and Bathing

3.3. Participants’ Knowledge Regarding Evidence-Based Clinical Practices for Preterm Neonatal Skin Care

3.4. Total Knowledge Score

3.5. Demographic and Occupational Characteristics Independently Associated with Participants’ Theoretical, Clinical and Total Knowledge Scores

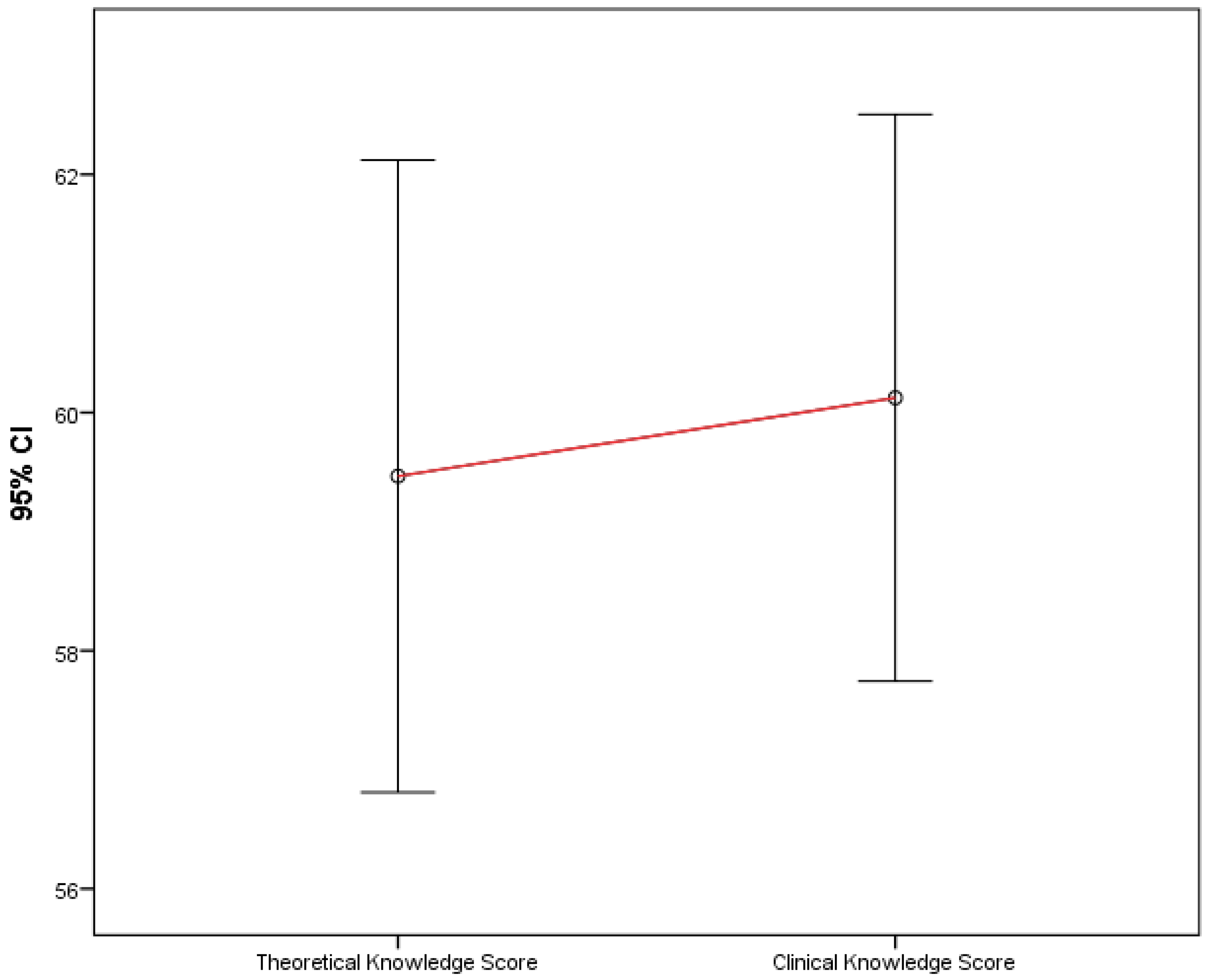

3.6. Comparison between Theoretical and Clinical Knowledge Scores

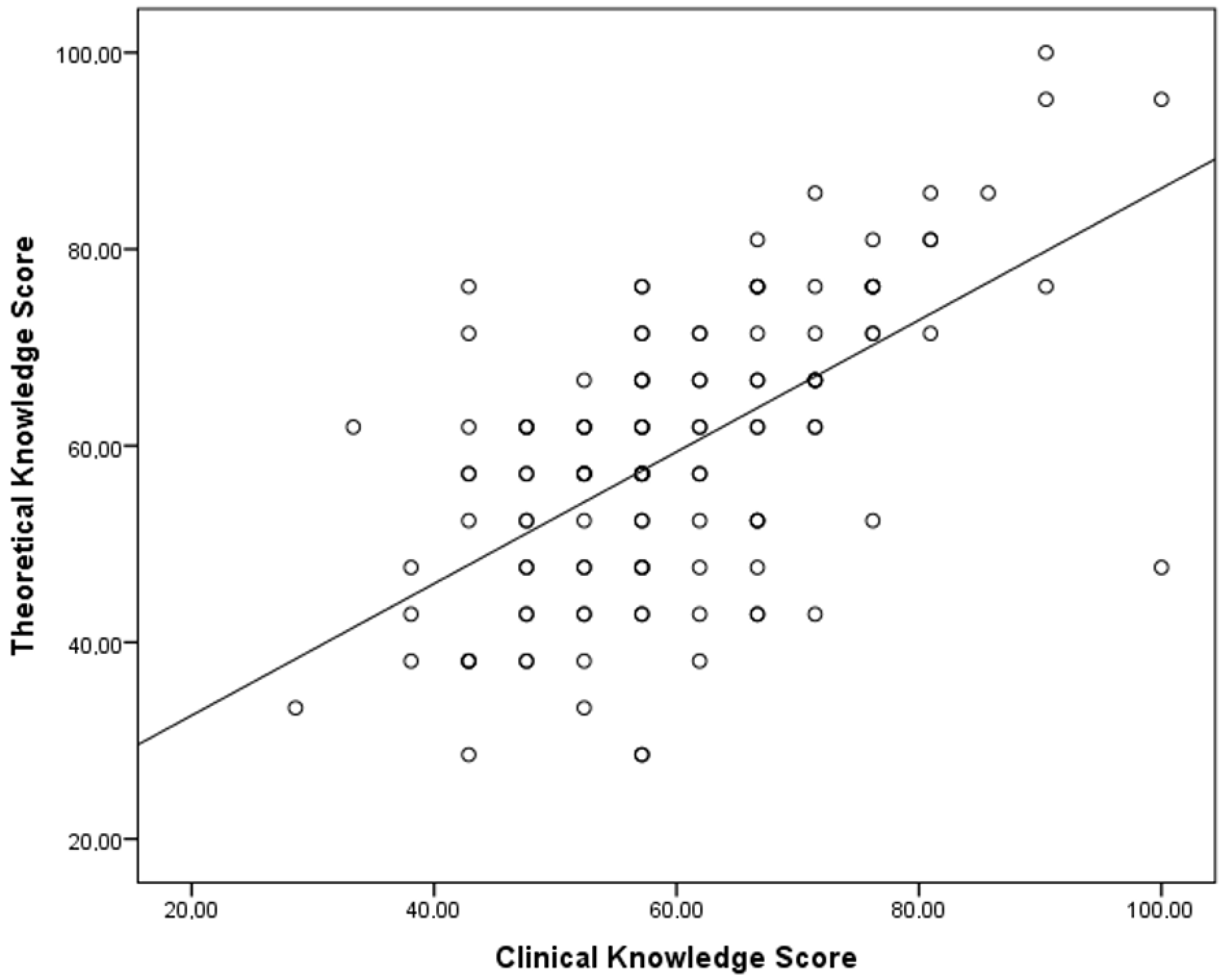

3.7. Correlation between Theoretical and Clinical Knowledge Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- New, K. Evidence-based guidelines for infant bathing. Res. Rev. 2019, 1–4. Available online: https://www.researchreview.co.nz/getmedia/0a9e5190-b8ac-419f-8f44-43b8e5ba8c4b/Educational-Series-Evidence-based-guidelines-for-infant-bathing.pdf.aspx?ext=.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Visscher, M.O.; Adam, R.; Brink, S.; Odio, M. Newborn infant skin: Physiology, development, and care. Clin. Dermatol. 2015, 33, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockenberry, M.J.; Rodgers, C.C.; Wilson, D. Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing, 11th ed.; Elsevier/Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2022; pp. 477–510. [Google Scholar]

- Lead Nurse Neonatal and Paediatric Services, Skin Care Guidelines for Neonates Including Care of Nappy Rash, Northern Devon Healthcare. 2019. Available online: https://www.northdevonhealth.nhs.uk (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Liversedge, H.L.; Bader, D.L.; Schoonhoven, L.; Worsley, P.R. Survey of neonatal nurses’ practices and beliefs in relation to skin health. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2018, 24, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Z.; Newton, J.M.; Lau, R. Malaysian nurses’ skin care practices of preterm infants: Experience vs. knowledge. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2014, 20, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. State of Health in the EU Greece Country Health Profile 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels. 2021. Available online: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Lorié, E.S.; Wreesmann, W.W.; van Veenendaal, N.R.; van Kempen, A.A.M.W.; Labrie, N.H.M. Parents’ needs and perceived gaps in communication with healthcare professionals in the neonatal (intensive) care unit: A qualitative interview study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 1518–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northern Devon District Hospital. Skin Care Guidelines for Neonates Including Care of Nappy Rash. Available online: https://www.northdevonhealth.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Skin-care-for-Neonates-guidelines-May-19.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Thames Valley Neonatal ODN Quality Care Group. Guideline Framework for Skin Integrity. Available online: https://southodns.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Skin-Integrity-Guideline-Dec-2019-Final.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Nishijima, K.; Yoneda, M.; Hirai, T.; Takakuwa, K.; Enomoto, T. Biology of the vernix caseosa: A review. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2019, 45, 2145–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on newborn health: Guidelines approved by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee. World Health Organization 2017. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259269 (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Blume-Peytavi, U.; Lavender, T.; Jenerowicz, D.; Ryumina, I.; Stalder, J.F.; Torrelo, A.; Cork, M.J. Recommendations from a European Roundtable Meeting on Best Practice Healthy Infant Skin Care. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2016, 33, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sarkar, M.; Davis, E.; Morphet, L.; Maloney, S.; Ilic, D.; Palermo, C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning in health professional education: A mixed methods study protocol. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Planning a Continuing Health Professional Education Institute. Continuing Professional Development: Building and Sustaining a Quality Workforce. In Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Volume 1. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219809/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Norman, M.K.; Lotrecchiano, G.R. Translating the learning sciences into practice: A primer for clinical and translational educators. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 5, e173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna, P.C. Skin Microbiome as Years Go By. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 21, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, J.C. Self-Study: A Method for Continuous Professional Learning and A Methodology for Knowledge Transfer. QANE AFI 2021, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemiparast, M.; Negarandeh, R.; Theofanidis, D. Exploring the barriers of utilizing theoretical knowledge in clinical settings: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 6, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saifan, A.; Devadas, B.; Daradkeh, F.; Hadya, A.F.; Mohannad, A.; Lintu, M.M. Solutions to bridge the theory-practice gap in nursing education in the UAE: A qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danesh, V.; Zuñiga, J.A.; Timmerman, G.M.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Cuevas, H.E.; Young, C.C.; Henneghan, A.M.; Morrison, J.; Kim, M.T. Lessons learned from eight teams: The value of pilot and feasibility studies in self-management science. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2021, 57, 151345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beebe, L.H. What can we learn from pilot studies? Perspect Psychiatr. Care 2007, 43, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panteli, D.; Legido-Quigley, H.; Reichebner, C.; Ollenschläger, G.; Schäfer, C.; Busse, R. Clinical Practice Guidelines as a quality strategy. In Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe: Characteristics, Effectiveness and Implementation of Different Strategies; Busse, R., Klazinga, N., Panteli, D., Quentin, W., Eds.; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549283/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 30 | 24.4 |

| Female | 93 | 75.6 |

| Age | ||

| 20–30 | 16 | 13.0 |

| 31–40 | 34 | 27.6 |

| 41–50 | 44 | 35.8 |

| 51–60 | 24 | 19.5 |

| 61 and above | 5 | 4.1 |

| Healthcare profession | ||

| Midwife | 65 | 52.8 |

| Nurse | 1 | 0.8 |

| Obstetrician | 24 | 19.5 |

| Pediatrician | 25 | 20.3 |

| Neonatologist | 8 | 6.5 |

| Educational status | ||

| University degree | 0 | 0.0 |

| Technical university degree | 40 | 32.5 |

| MSc | 45 | 36.6 |

| PhD | 38 | 30.9 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employee in private sector | 23 | 18.7 |

| Employee in public sector | 83 | 67.5 |

| Self-employed | 17 | 13.8 |

| Academic | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total working experience | ||

| 0–5 years | 28 | 22.8 |

| 6–10 years | 22 | 17.9 |

| 11–15 years | 22 | 17.9 |

| 16–20 years | 23 | 18.7 |

| More than 20 years | 28 | 22.8 |

| Geographical area of current work | ||

| Within the prefecture of Attica | 22 | 17.9 |

| Outside the prefecture of Attica | 101 | 82.1 |

| Level of healthcare of current work | ||

| Primary healthcare | 33 | 26.8 |

| Secondary healthcare | 55 | 44.7 |

| Tertiary healthcare | 35 | 28.5 |

| Your theoretical knowledge about neonatal vernix caseosa, skin microbiota, bathing and clinical practices for neonatal skin care mainly derives from | ||

| Undergraduate studies | 21 | 17.1 |

| Postgraduate studies | 2 | 1.6 |

| Professional experience | 64 | 52.0 |

| Personal study and research | 19 | 15.4 |

| Seminars/Congresses/Lectures/Courses | 13 | 10.6 |

| Other source | 4 | 3.3 |

| N | % | Correct Answer (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vernix Caseosa is Composed of | 49.6 | ||

| water (90%)–lipids (5%)–proteins (5%) | 8 | 6.5 | |

| water (80%)–lipids (10%)–proteins (10%) * | 61 | 49.6 | |

| water (70%)–lipids (20%)–proteins (10%) | 37 | 30.1 | |

| water (60%)–lipids (20%)–proteins (20%) | 17 | 13.8 | |

| There are no differences in the lipid composition of vernix caseosa and the stratum corneum. | 71.5 | ||

| True | 35 | 28.5 | |

| False * | 88 | 71.5 | |

| Vernix caseosa is | 78.0 | ||

| Hydrophobic * | 96 | 78.0 | |

| Hydrophilic | 27 | 22.0 | |

| Vernix caseosa is more vapor-permeable than stratum corneum | 40.7 | ||

| True | 73 | 59.3 | |

| False * | 50 | 40.7 | |

| The preservation of the vernix caseosa facilitates formation of the acid mantle of the neonatal skin. | 91.1 | ||

| Right * | 112 | 91.1 | |

| Wrong | 11 | 8.9 | |

| Vernix caseosa has | 87.0 | ||

| Antimicrobial and healing properties | 9 | 7.3 | |

| Thermoregulation properties | 7 | 5.7 | |

| Antioxidant properties | 0 | 0.0 | |

| All the above * | 107 | 87.0 | |

| None of the above | 0 | 0.0 | |

| The anti-inflammatory properties of the vernix caseosa are related to | 30.9 | ||

| Fungi | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Bacteria | 5 | 4.1 | |

| Viruses | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Fungi and bacteria * | 38 | 30.9 | |

| All the above | 79 | 64.2 | |

| The stratum corneum (the outer layer of the skin) of term neonates consists of | 36.0 | ||

| 2–4 layers | 14 | 11.6 | |

| 4–8 layers | 36 | 29.5 | |

| 10–20 layers * | 44 | 36.0 | |

| 20–30 layers | 28 | 23.0 | |

| The stratum corneum (the outer layer of the skin) of an extremely preterm neonate consists of | 52.0 | ||

| 2–3 layers * | 64 | 52.0 | |

| 7–8 layers | 49 | 39.8 | |

| 10–12 layers | 5 | 4.1 | |

| 13–15 layers | 5 | 4.1 | |

| Neonatal skin maturation continues until the age of | 53.7 | ||

| 30 days of life | 17 | 13.8 | |

| 3 months | 15 | 12.2 | |

| 6 months | 25 | 20.3 | |

| 12 months * | 66 | 53.7 | |

| The use of incubator humidity during the first 2 weeks of life in extremely preterm neonates | 85.8 | ||

| Increases transepidermal water loss | 17 | 14.2 | |

| Decreases transepidermal water loss * | 105 | 85.8 | |

| Transepidermal water loss in preterm neonates is increased due to | 66.3 | ||

| Insufficiency of the stratum corneum * | 81 | 66.3 | |

| Insufficient subcutaneous fat stores | 41 | 33.7 | |

| Neonatal skin microbiota is initially established | 23.6 | ||

| Immediately after birth | 80 | 65.0 | |

| 3–4 days after birth * | 29 | 23.6 | |

| 1 month after birth | 13 | 10.6 | |

| 1 year after birth | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Initial colonization of the neonatal skin is dependent on | 86.2 | ||

| Mode of delivery * | 106 | 86.2 | |

| Feeding type | 6 | 4.9 | |

| Skin care | 11 | 8.9 | |

| Early–life neonatal skin microbiota varies significantly among different body sites | 26.8 | ||

| True | 90 | 73.2 | |

| False * | 33 | 26.8 | |

| The microbial flora of the neonatal skin is more diverse in | 18.7 | ||

| Moist skin areas | 34 | 27.6 | |

| Dry skin areas * | 23 | 18.7 | |

| Sebacous skin areas | 66 | 53.7 | |

| Intravenous antibiotics can affect neonatal skin microbiota | 93.9 | ||

| True * | 115 | 93.9 | |

| False | 7 | 6.1 | |

| The NICU environment can affect the development of skin microbiota in preterm neonates | 97.6 | ||

| True * | 120 | 97.6 | |

| False | 3 | 2.4 | |

| Dysbiosis of neonatal skin microbiota can cause | 72.4 | ||

| Eczema/atopic dermatitis | 27 | 22.0 | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 3 | 2.4 | |

| Asthma | 0 | 0.0 | |

| All the above * | 89 | 72.4 | |

| None of the above | 4 | 3.3 | |

| The corneal blink reflex, which importantly protects the neonatal eye during bathing, matures fully after | 45.5 | ||

| 7 days of life | 15 | 12.2 | |

| 14 days of life | 11 | 8.9 | |

| 30 days of life | 41 | 33.3 | |

| 120 days of life * | 56 | 45.5 | |

| The first bathing of a neonate whose mother is HIV positive must occur | 43.1 | ||

| Immediately after birth | 50 | 40.7 | |

| As soon as possible after birth * | 53 | 43.1 | |

| 6–24 h after birth | 20 | 16.3 | |

| Theoretical Knowledge Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | p ANOVA | ||

| Gender | Male | 59.52 | 16.10 | 0.981 * |

| Female | 59.45 | 14.55 | ||

| Age | 20–40 | 55.71 | 11.79 | 0.003 |

| 41–50 | 58.66 | 16.10 | ||

| 51 and above | 67.16 | 15.34 | ||

| Healthcare profession | Midwife/Nurse | 56.06 | 15.69 | 0.006 * |

| Obstetrician/Pediatrician/Neonatologist | 63.41 | 12.92 | ||

| Educational status | Technical university degree | 57.02 | 15.90 | 0.443 |

| Master’s degree | 60.32 | 11.31 | ||

| Doctoral degree | 61.03 | 17.36 | ||

| Employment status | Employee in private sector | 55.28 | 14.69 | 0.327 |

| Employee in public sector | 60.36 | 14.61 | ||

| Self-employed | 60.78 | 16.28 | ||

| Total working experience | 0–5 years | 59.18 | 11.11 | 0.223 |

| 6–10 years | 54.11 | 13.91 | ||

| 11–15 years | 57.58 | 17.20 | ||

| 16–20 years | 62.53 | 15.94 | ||

| More than 20 years | 62.93 | 15.57 | ||

| Geographical area of current work | Within the prefecture of Attica | 53.90 | 14.50 | 0.050 * |

| Outside the prefecture of Attica | 60.68 | 14.75 | ||

| Level of healthcare of current work | Primary healthcare | 58.44 | 15.53 | 0.106 |

| Secondary healthcare | 62.42 | 14.42 | ||

| Tertiary healthcare | 55.78 | 14.41 | ||

| Your theoretical knowledge about neonatal vernix caseosa, skin microbiota, bathing and clinical practices for neonatal skin care mainly derives from | Undergraduate / Postgraduate studies | 54.04 | 13.67 | 0.013 |

| Professional experience | 59.45 | 14.07 | ||

| Personal study and research | 68.42 | 18.04 | ||

| Seminars/Congresses/Lectures/ Courses/Other source | 56.86 | 11.84 | ||

| N | % | Correct Answer (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The skin surface pH of preterm neonates in the first day of life is | 65.9 | ||

| >6 * | 81 | 65.9 | |

| 6 | 20 | 16.3 | |

| <6 | 22 | 17.9 | |

| The skin surface pH of preterm neonates reaches the value of 5 | 28.5 | ||

| At the end of the first week of life | 30 | 24.4 | |

| At the end of the second week of life | 58 | 47.2 | |

| At the end of the third week of life * | 35 | 28.5 | |

| What percentage does the skin itself provide of the body weight of a preterm neonate? | 64.2 | ||

| 3 | 26 | 21.1 | |

| 13 * | 79 | 64.2 | |

| 23 | 18 | 14.6 | |

| Neonates with gestational age < 32 weeks once cardioraspiratory and thermal stability is achieved, can be bathed for the first time after | 45.5 | ||

| 1st–2nd day of life | 8 | 6.5 | |

| 3rd–5th day of life * | 56 | 45.5 | |

| 5th–7th day of life | 44 | 35.8 | |

| 9th–10th day of life | 15 | 12.2 | |

| In neonates with gestational age < 32 weeks the use of appropriate cleansers is safe after | 65.0 | ||

| 24 h of life | 7 | 5.7 | |

| 2–3 days of life | 16 | 13.0 | |

| The first week of life * | 80 | 65.0 | |

| The first 10 days of life | 20 | 16.3 | |

| To reduce stress in preterm neonates the recommended bathing technique is | 14.6 | ||

| Warm wet washcloths inside the incubator | 68 | 55.3 | |

| Immersion bath | 37 | 30.1 | |

| Swaddled immersion bath * | 18 | 14.6 | |

| In preterm neonates.in order to protect the stratum corneum, the nappy area should be cleaned only with water for the first | 25.2 | ||

| 10 days of life | 35 | 28.5 | |

| 2 weeks of life | 51 | 41.5 | |

| 4 weeks of life * | 31 | 25.2 | |

| 8 weeks of life | 6 | 4.9 | |

| In preterm neonates a barrier cream for the nappy area should be applied | 44.7 | ||

| At each nappy change | 44 | 35.8 | |

| Since the first signs of redness appear * | 55 | 44.7 | |

| In severe nappy rash | 24 | 19.5 | |

| In preterm neonates, red, scaly skin with excoriations in the groin and neck folds may be due to lack of | 42.3 | ||

| Iron | 6 | 4.9 | |

| Zinc * | 52 | 42.3 | |

| Vitamin E | 65 | 52.8 | |

| To maintain the skin integrity of preterm neonates it is indicated the use of emollient with | 30.1 | ||

| Sunflower oil * | 37 | 30.1 | |

| Cedar oil | 7 | 5.7 | |

| All the above | 20 | 16.3 | |

| None of the above | 59 | 48.0 | |

| In preterm neonates, the use of inappropriate detergents in the linen and clothing may affect neonatal skin microbiome | 98.4 | ||

| Right * | 121 | 98.4 | |

| Wrong | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Prophylactic emollient use in preterm neonates weighing 750 gr or less is associated with an increased risk of infection | 91.1 | ||

| True * | 112 | 91.1 | |

| False | 11 | 8.9 | |

| In extremely preterm neonates the epidermal barrier function during the first days of life can be promoted through | 67.5 | ||

| The use of appropriate moisturizing products | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Skin to skin contact with the parent | 38 | 30.9 | |

| The use of appropriate incubator humidification * | 83 | 67.5 | |

| In preterm neonates, when there is an open wound on the skin, this should be | 73.2 | ||

| Covered with sterile material in order to prevent infection * | 90 | 73.2 | |

| Left uncovered to “air-out” and thus heal faster | 33 | 26.8 | |

| In preterm neonates with gestational age < 32 weeks, the use of inotropes is a risk factor for skin breakdown | 84.6 | ||

| True * | 104 | 84.6 | |

| False | 19 | 15.4 | |

| Monitor probes can lead to local skin necrosis due to pressure in preterm neonates with oedematous dermis | 90.2 | ||

| True * | 111 | 90.2 | |

| False | 12 | 9.8 | |

| In preterm neonates, the use of skin-protective film is suggested before the use of adhesive dressings and tapes | 87.8 | ||

| True * | 108 | 87.8 | |

| False | 15 | 12.2 | |

| In preterm neonates, adhesive tapes are suggested to be removed with | 92.7 | ||

| Warm water only * | 114 | 92.7 | |

| Antiseptic solution | 5 | 4.1 | |

| Alcoholic solution | 4 | 3.3 | |

| In preterm neonates, intravenous lines should be observed for signs of infiltration every | 26.0 | ||

| 1 h * | 32 | 26.0 | |

| 3 h | 72 | 58.5 | |

| 6 h | 10 | 8.1 | |

| 8 h | 9 | 7.3 | |

| In preterm neonates, application of protective dressings is suggested when nasal CPAP devices are used | 95.1 | ||

| True * | 117 | 95.1 | |

| False | 6 | 4.9 | |

| Neonatal Skin Risk Assessment Scales in preterm neonates admitted to the NICU should be completed | 30.1 | ||

| Upon admission | 77 | 62.6 | |

| Within 2 h of admission * | 37 | 30.1 | |

| Within 12 h of admission | 3 | 2.4 | |

| Within 24 h of admission | 6 | 4.9 | |

| Clinical Knowledge Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | p ANOVA | ||

| Gender | Male | 60.00 | 12.54 | 0.954 * |

| Female | 60.16 | 13.65 | ||

| Age | 20–40 | 57.52 | 10.13 | 0.016 |

| 41–50 | 59.09 | 12.72 | ||

| 51 and above | 66.17 | 17.19 | ||

| Healthcare profession | Midwife/Nurse | 57.43 | 12.94 | 0.015 * |

| Obstetrician/Pediatrician/Neonatologist | 63.24 | 13.22 | ||

| Educational status | Technical university degree | 58.10 | 12.63 | 0.079 |

| Master’s degree | 58.52 | 10.23 | ||

| Doctoral degree | 64.16 | 16.41 | ||

| Employment status | Employee in private sector | 58.80 | 14.47 | 0.494 |

| Employee in public sector | 59.78 | 13.94 | ||

| Self-employed | 63.59 | 7.52 | ||

| Total working experience | 0–5 years | 58.67 | 10.92 | 0.351 |

| 6–10 years | 59.31 | 9.49 | ||

| 11–15 years | 57.36 | 13.59 | ||

| 16–20 years | 65.01 | 16.16 | ||

| More than 20 years | 60.37 | 15.12 | ||

| Geographical area of current work | Within the prefecture of Attica | 58.44 | 15.14 | 0.516 * |

| Outside the prefecture of Attica | 60.49 | 12.96 | ||

| Level of healthcare of current work | Primary healthcare | 59.60 | 12.77 | 0.946 |

| Secondary healthcare | 60.09 | 13.36 | ||

| Tertiary healthcare | 60.68 | 14.16 | ||

| Your knowledge about neonatal vernix caseosa, skin microbiota, bathing and clinical practices for neonatal skin care mainly derives from | Undergraduate/Postgraduate studies | 55.07 | 12.08 | <0.001 |

| Professional experience | 59.82 | 11.81 | ||

| Personal study and research | 70.93 | 16.56 | ||

| Seminars/Congresses/Lectures/ Courses/Other source | 56.02 | 10.18 | ||

| Total Knowledge Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | p ANOVA | ||

| Gender | Male | 59.76 | 13.21 | 0.987 * |

| Female | 59.81 | 12.50 | ||

| Age | 20–40 | 56.62 | 9.00 | 0.002 |

| 41–50 | 58.87 | 13.36 | ||

| 51 and above | 66.67 | 14.50 | ||

| Healthcare profession | Midwife/Nurse | 56.75 | 12.71 | 0.004 * |

| Obstetrician/Pediatrician/Neonatologist | 63.32 | 11.67 | ||

| Educational status | Technical university degree | 57.56 | 12.86 | 0.207 |

| Master’s degree | 59.42 | 9.66 | ||

| Doctoral degree | 62.59 | 15.06 | ||

| Employment status | Employee in private sector | 57.04 | 13.32 | 0.422 |

| Employee in public sector | 60.07 | 12.91 | ||

| Self-employed | 62.18 | 9.96 | ||

| Total working experience | 0–5 years | 58.93 | 9.25 | 0.282 |

| 6–10 years | 56.71 | 9.90 | ||

| 11–15 years | 57.47 | 14.66 | ||

| 16–20 years | 63.77 | 13.94 | ||

| More than 20 years | 61.65 | 14.25 | ||

| Geographical area of current work | Within the prefecture of Attica | 56.17 | 12.85 | 0.138 |

| Outside the prefecture of Attica | 60.58 | 12.50 | ||

| Level of healthcare of current work | Primary healthcare | 59.02 | 12.98 | 0.501 |

| Secondary healthcare | 61.26 | 12.89 | ||

| Tertiary healthcare | 58.23 | 11.95 | ||

| Your knowledge about neonatal vernix caseosa, skin microbiota, bathing and clinical practices for neonatal skin care mainly derives from | Undergraduate / Postgraduate studies | 54.55 | 10.89 | 0.001 |

| Professional experience | 59.64 | 11.36 | ||

| Personal study and research | 69.67 | 15.85 | ||

| Seminars/Congresses/Lectures/ Courses/Other source | 56.44 | 9.70 | ||

| Clinical Knowledge Score | ||

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Knowledge Score | r | 0.60 |

| p | <0.001 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Metallinou, D.; Nanou, C.; Tsafonia, P.; Karampas, G.; Lykeridou, K. Investigation of Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge of Evidence-Based Clinical Practices for Preterm Neonatal Skin Care—A Pilot Study. Children 2022, 9, 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081235

Metallinou D, Nanou C, Tsafonia P, Karampas G, Lykeridou K. Investigation of Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge of Evidence-Based Clinical Practices for Preterm Neonatal Skin Care—A Pilot Study. Children. 2022; 9(8):1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081235

Chicago/Turabian StyleMetallinou, Dimitra, Christina Nanou, Panagiota Tsafonia, Grigorios Karampas, and Katerina Lykeridou. 2022. "Investigation of Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge of Evidence-Based Clinical Practices for Preterm Neonatal Skin Care—A Pilot Study" Children 9, no. 8: 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081235

APA StyleMetallinou, D., Nanou, C., Tsafonia, P., Karampas, G., & Lykeridou, K. (2022). Investigation of Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge of Evidence-Based Clinical Practices for Preterm Neonatal Skin Care—A Pilot Study. Children, 9(8), 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081235