Resilience: Conceptualization and Keys to Its Promotion in Educational Centers

Abstract

1. Introduction

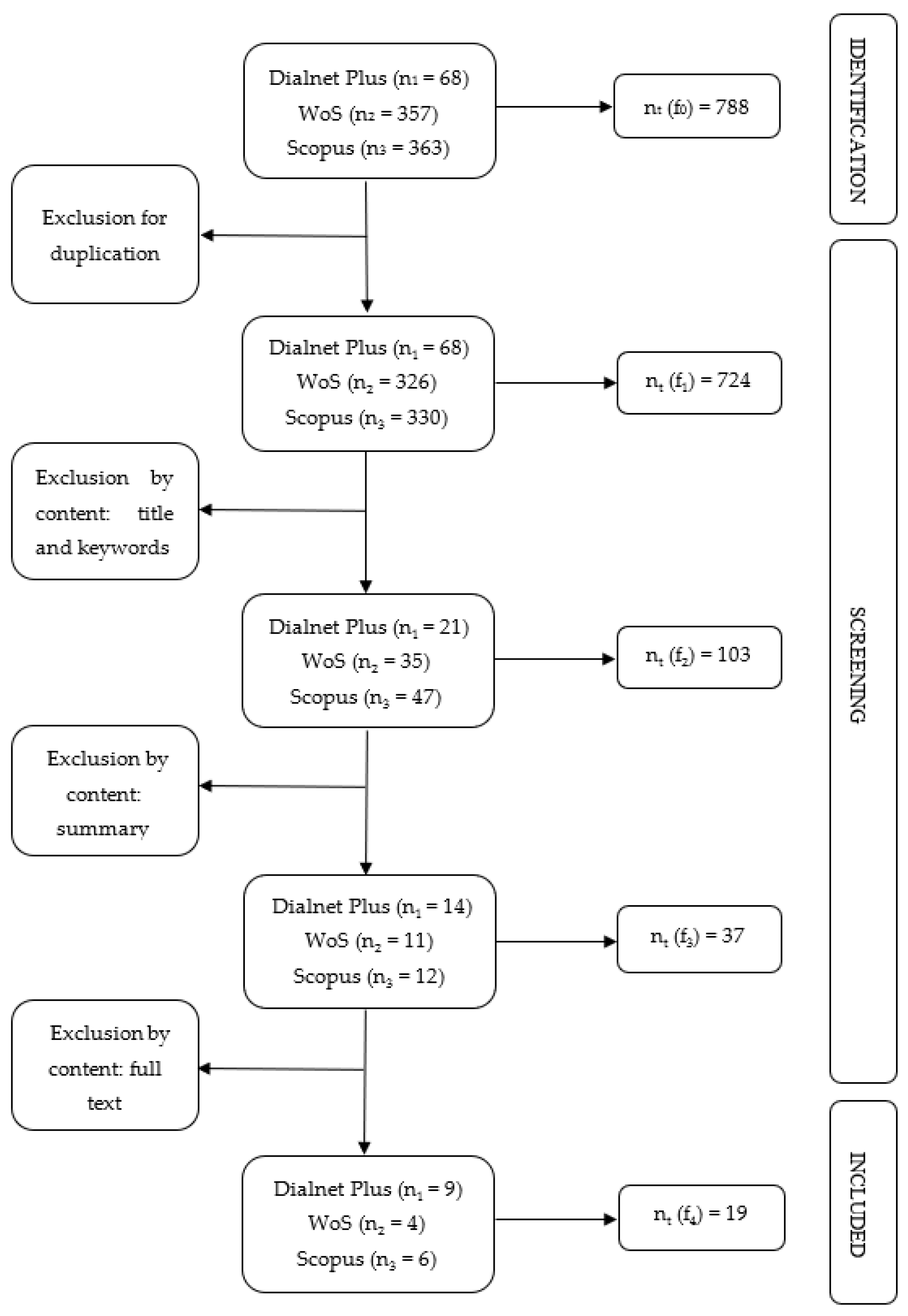

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies and Selection of Studies

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Lines of Resilience Research and the Evolution of the Field of Study

3.1.1. First Line: Protective Factors

3.1.2. Second Line: Resilience as a Process

To speak of resilience in terms of the individual is a fundamental error. One is not more or less resilient, as if one possessed a catalog of qualities: innate intelligence, resistance to pain, or the molecule of humor. Resilience is a process, a becoming of the child who, by dint of actions and words, inscribes his development in an environment and writes his history in a culture. Consequently, it is not so much the child who is resilient as its evolution and its process of vertebration of its own history.(p. 214)

3.1.3. Third Line: The Will to Resurgence

The person has a more active role not as the possessor of specific characteristics, but as the subject of his or her own history that he or she weaves, necessarily, within his or her social and cultural context. From this vision of resilience is transferred the power of choice in the face of adversity, consisting in not letting oneself be defeated, in divesting oneself of the condition of victim.(p. 33)

3.2. Resilience and Neuroscience

Behind every thought and every behavior there is a brain wiring responsible. Our behavior is a consequence of how our brain works and this is not only determined by our genome. Today we know the great importance of the influence of the environment and the attitude towards it in determining our brain wiring.[38] (p. 137)

- The resilient response is an idiosyncratic process that every person can develop at any time in his or her life cycle, based on the willingness to activate and use his or her personal abilities and skills, the support of significant people and the use of other environmental resources.

- The resilient process, like all learning, generates a restructuring of neural networks that is possible thanks to the production of new neurons and brain plasticity. This possibility of modification makes it possible to learn new adaptive skills, unlearn other maladaptive ones and develop new habits of thought and behavior that can affect the expression or silencing of certain genes.

- This process, which can be activated in the face of adversity, implies a positive evolution of the person, which develops and/or reinforces his or her competencies and projects him or her towards the future with greater self-confidence to face new challenges.

3.3. Promoting Resilience in Schools

The school, understood as a center of health and socialization, is a potential space to promote resilient people (…) the emphasis of public policies should focus on the development of human capabilities, that is, on an education for life.[40] (p. 214)

(…) the encounter with a significant person. Sometimes it is enough with one, a teacher who with a phrase gave hope back to the child, a sports instructor who made him understand that human relationships could be easy, a priest who transfigured suffering into transcendence, a gardener, a comedian, a writer, anyone could give body to the simple meaning: “It is possible to come out successful”.[33] (p. 214)

The role of the educator (…) beyond delivering a set of knowledge that exists by itself, must promote the construction of this knowledge to encourage the empowerment of the student. His mission is to help the student discover his potential so that he can build his own life project based on autonomous and responsible decisions.(p. 117)

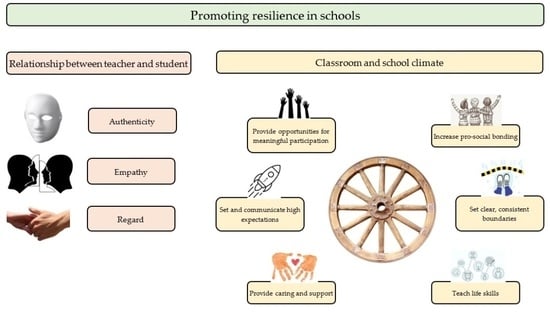

3.3.1. The Relationship between the Teacher and the Student

The Authenticity of the Teacher

Unconditional Positive Regard for the Student

Empathic Understanding

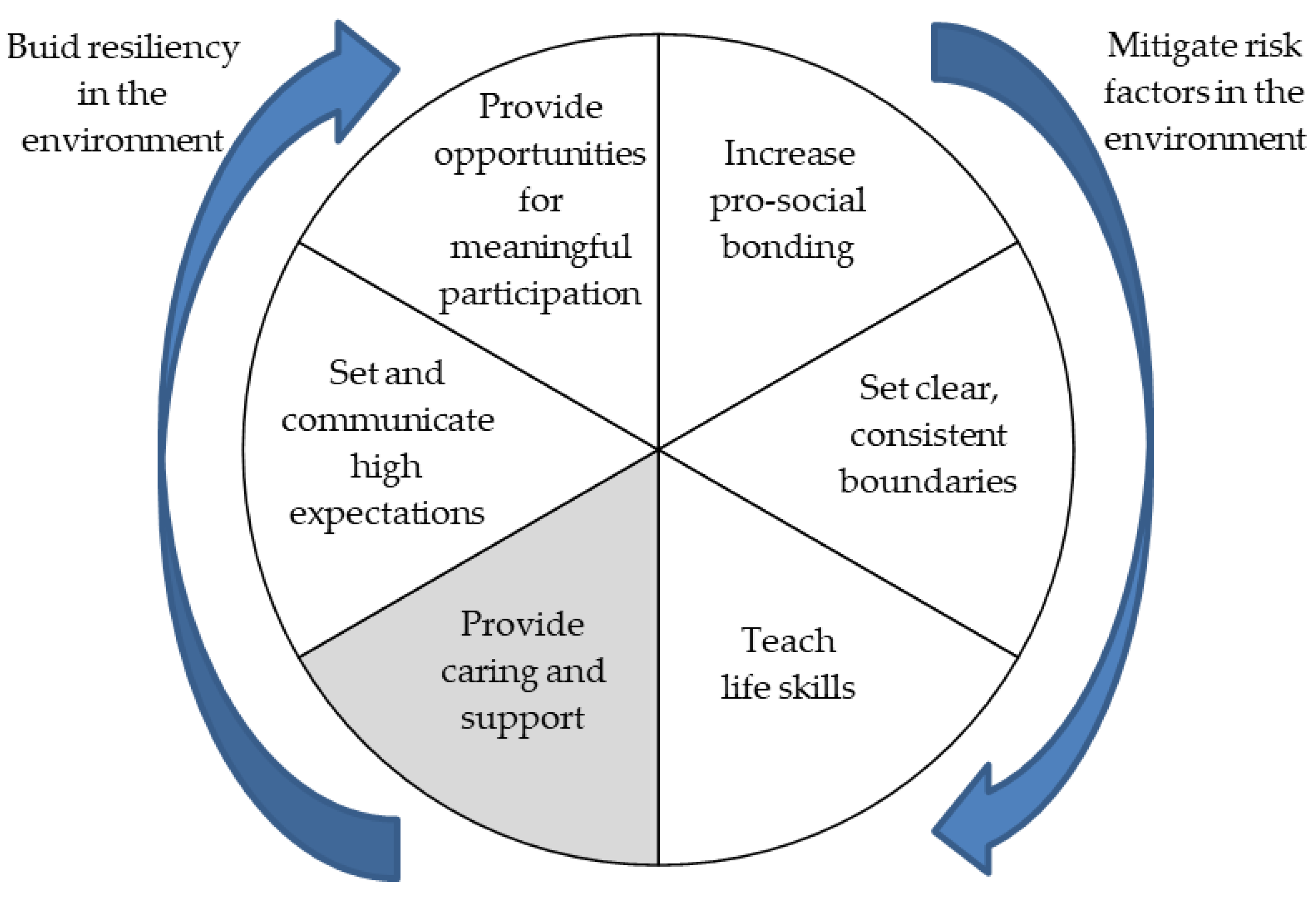

3.3.2. Classroom and School Climate

Increase Pro-Social Bonding

Set Clear, Consistent Boundaries

Teach Life Skills

Provide Caring and Support

Set and Communicate High Expectations

Provide Opportunities for Meaningful Participation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grotberg, E.H. Guía de Promoción de la Resiliencia en los Niños, para Fortalecer el Espíritu Humano; Fundación Bernard Van Leer: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grotberg, E.H. Nuevas tendencias en resiliencia. In Resiliencia: Descubriendo las Propias Fortalezas; Melillo, A., Suárez Ojeda, N., Eds.; Paidós: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2001; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar, S.S.; Ciccheti, D.; Becker, B. The construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, N. Resiliencia y Personalidad en Niños y Adolescentes. Cómo Desarrollarse en Tiempos de Crisis; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México: México city, México, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Panez, R. Bases teóricas del modelo peruano de promoción de resiliencia. In CODINFA, Por los Caminos de la Resiliencia. Proyectos de Promoción en Infancia Andina; Panez y Silva: Lima, Perú, 2002; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J. Resilience to childhood adversity: Results of a 21-year study. In Resilience and Vulnerability: Adaptation in the Context of Childhood Adversities; Luthar, S.S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 130–155. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, E.; Martínez, C.; Pandolfi, M.; Penroz, K.; Díaz, F. Resiliencia: La Esencia Humana de la Transformación Frente a la Adversidad; Universidad de la Concepción: Santiago, Chile, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorders. Br. J. Psychiatr. 1985, 147, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamas, H. Salud: Resiliencia y Bienestar Psicológico; Colegio de Psicólogos del Perú: Lima, Perú, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kotliarenco, M.A.; Dueñas, V. Vulnerabilidad versus resiliente: Una propuesta de acción educativa. Rev. Derecho A La Infanc. 1994, 9, 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, G.O. Resilient Adults: Overcoming a Cruel Past; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, A.; Sanz, R. Reflexiones y propuestas prácticas para desarrollar la capacidad de resiliencia frente a los conflictos en la escuela. Publicaciones 2019, 49, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegret, J.; Castanys, E.; Sellarès, R. Alumnado en Situación de Estrés Emocional; Graó: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 21, 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Real Academia Española. Diccionario de la Lengua Española, 23rd ed.; Espasa: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, G.E. The metatheory of Resilience and Resiliency. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, G.E. La resiliencia: Conceptos y modelos aplicables al entorno escolar. Rev. Guiniguada 2010, 19, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Manciaux, M.; Vanistendael, S.; Lecomte, J.; Cyrulnik, B. La resiliencia: Estado de la cuestión. In La Resiliencia: Resistir y Rehacerse; Manciaux, M., Ed.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, N.; Milstein, M. Resiliencia en la Escuela, 2nd ed.; Paidós: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S.; Coatsworth, J.D. The Development of Competence in Favorable and Unfavorable Environments. Lessons from Research on Successful Children. Am. Psychol. 1998, 53, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grotberg, E.H. A guide to promoting resilience in children: Strengthening the human spirit. Early Child. Dev. Pract. Reflect. 1995, 8, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Grotberg, E.H. La Resiliencia en el Mundo de Hoy. Cómo Superar las Adversidades; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Villalba, C. El concepto de resiliencia. Aplicaciones en la intervención social. Interv. Psicosoc. 2003, 12, 283–299. [Google Scholar]

- Becoña, E. Resiliencia y consumo de drogas: Una revisión. Adicciones 2006, 1, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, G.; Rubio, J.L. Manual de Resiliencia Aplicada; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wolin, S.J.; Wolin, S. The Resilient Self: How Survivors of Troubled Families Rise above Adversity; Willard Books: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, L. Superar la Adversidad. El Poder de la Resiliencia; Espasa: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, R. Levantarse y luchar, 3rd ed.; Conecta: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Linares, R. Resiliencia o la Adversidad Como Oportunidad; Espuela de Plata: Sevilla, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Román, C.; Juárez, J.; Molina, L. Evolución y nuevas perspectivas del concepto de resiliencia: De lo individual a los contextos y a las relaciones socioeducativas. Educatio Siglo XXI 2020, 38, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, G.E. Los Procesos Holísticos de Resiliencia en el Desarrollo de Identidades Autorreferenciadas en Lesbianas, Gays y Bisexuales. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Palmas, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cyrulnik, B. Los Patitos Feos. La Resiliencia: Una Infancia Infeliz no Determina la Vida, 7th ed.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P.; Steele, M.; Steele, H.; Higgitt, A.; Target, M. The Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 1992. The Theory and Practice of Resilience. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1994, 35, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theis, A. La resiliencia en la literatura científica. In La Resiliencia: Resistir y Rehacerse; Manciaux, M., Ed.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Grané, J.; Forés, A. Los Patitos Feos y los Cisnes Negros. Resiliencia y Neurociencia; Plataforma Actual: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Casafont, R. Educar-nos para Educar; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Casafont, R. Viatge al teu Cervell; Edicions B: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Casafont, R. Viatge al teu Cervell Emocional; Edicions B: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Salvo, S.; Bravo-Sanzana, M.; Miranda-Vargas, H.; Forés, A.; Mieres-Chacaltana, M. ¿La promoción de la resiliencia en la escuela puede contribuir con la política pública de salud? Salud PúblicaMéxico 2017, 59, 214–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tipismana, O. Factores de Resiliencia y Afrontamiento como Predictores del Rendimiento Académico de los Estudiantes en Universidades Privadas. REICE-Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2019, 17, 147–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forés, A.; Grané, J. La Resiliencia en Entornos Socioeducativos; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- García-Yepes, N. Papel del docente y de la escuela en el fortalecimiento de los proyectos de vida alternativos (PVA). Rev. Colomb. De Educ. 2020, 1, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rygaard, N.P. El Niño Abandonado. Guía para el Tratamiento de los Trastornos de Apego; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C.R. El Proceso de Convertirse en Persona, 17th ed.; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo, J.L. Guía para el Apoyo Educativo de Niños con Trastornos de Apego. LibrosEnRed. 2009. Available online: https://bookstore.librosenred.com/libros/guiaparaelapoyoeducativodeninoscontrastornosdeapego.html (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Barceló, T. Crecer en Grupo. Una Aproximación Desde el Enfoque Centrado en la Persona, 2nd ed.; Desclée de Brouwer: Bilbao, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Honsinger, C.; Brown, M.H. Preparing Trauma-Sensitive Teachers: Strategies for Teacher Educators. Teach. Educ. J. 2019, 12, 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gerver, R. Crear Hoy la Escuela del Mañana, 3rd ed.; Ediciones SM: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Database | Selection Criteria |

|---|---|

| Dialnet Plus |

|

| WoS |

|

| Scopus |

|

| Database | Search Equations | Results | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dialnet Plus | (resiliencia OR resiliente) AND (escuel* OR escolar OR colegi* OR “centr* educativ*”) AND (emocional* OR conduct*) NOT (universidad OR adultos) | 68 | 9 April 2022 |

| WoS | (resilience OR resilient OR resiliency) AND school AND (emotional OR behavioral) NOT (adolescen* OR teen* OR high OR college OR university OR adult) | 357 | 9 April 2022 |

| Scopus | (resilience OR resilient OR resiliency) AND school AND (emotional OR behavioral) AND NOT (adolescen* OR teen* OR high OR college OR university OR adult) | 363 | 9 April 2022 |

| Total | 788 | 9 April 2022 |

| Authors | Year | Title | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyrulnik, B. | 2006 | Los patitos feos. La resiliencia: una infancia infeliz no determina la vida. | Book |

| Fonagy, P.; et al. | 1994 | The Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 1992. The Theory and Practice of Resilience. | Article |

| Forés, A.; Grané, J. | 2012 | La resiliencia en entornos socioeducativos. | Book |

| García-Yepes, N. | 2020 | Papel del docente y de la escuela en el fortalecimiento de los proyectos de vida alternativos (PVA). | Article |

| Gil, G.E. | 2010 | Los procesos holísticos de resiliencia en el desarrollo de identidades autorreferenciadas en lesbianas, gays y bisexuales. | Thesis |

| Gil, G.E. | 2010 | La resiliencia: conceptos y modelos aplicables al entorno escolar. | Article |

| Grotberg, E.H. | 1995 | A guide to promoting resilience in children: strengthening the human spirit. | Article |

| Henderson, N.; Milstein, M. | 2005 | Resiliencia en la escuela. | Book |

| Honsinger, C.; Brown, M.H. | 2019 | Preparing Trauma-Sensitive Teachers: Strategies for Teacher Educators. | Article |

| Luthar, S.S.; et al. | 2000 | The construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work. | Article |

| Manciaux, M.; et al. | 2010 | La resiliencia: estado de la cuestión. | Chapter |

| Masten, A.S.; Coatsworth, J.D. | 1998 | The Development of Competence in Favorable and Unfavorable Environments. Lessons from Research on Successful Children. | Article |

| Puig, G.; Rubio, J.L. | 2011 | Manual de resiliencia aplicada. | Book |

| Richardson, G.E. | 2002 | The metatheory of Resilience and Resiliency. | Article |

| Ruiz-Román, C.; et al. | 2020 | Evolución y nuevas perspectivas del concepto de resiliencia: de lo individual a los contextos y a las relaciones socioeducativas. | Article |

| Rygaard, N.P. | 2008 | El niño abandonado. Guía para el tratamiento de los trastornos de apego. | Book |

| Salvo, S.; et al. | 2017 | ¿La promoción de la resiliencia en la escuela puede contribuir con la política pública de salud? | Article |

| Theis, A. | 2010 | La resiliencia en la literatura científica. | Chapter |

| Villalba, C. | 2003 | El concepto de resiliencia. Aplicaciones en la intervención social. | Article |

| Authors | Protective Factors Specific to the Individual | Protective Factors Present in the Family and the Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Werner and Smith (1982, 1992) | Be female, physically strong, goal-oriented, adaptable, tolerant, a good communicator, socially responsible and have high self-esteem. | Have a good supportive environment within and outside the family. |

| Rutter (1979, 1985) | Being female, having a good temperament, self-control, perceived self-efficacy and planning skills. | Have a close, warm and stable personal relationship with at least one adult and a positive school climate. |

| Garmezy, Masten and Tellegen (1984); Garmezy (1991) | Temperament and personality attributes: having high expectations, reflective ability, good cognitive skills, positive outlook, high self-esteem, internal locus of control, self-discipline, problem-solving skills, critical thinking skills and sense of humor. | Family: good family cohesion that provides affection, presence of a relative other than the parents (grandparent…) who assumes the parental role in their absence or in case of relationship problems between them. Social support: availability of an adult who assumes the parental role if necessary, presence of a teacher who is interested in the child, and an organization or institution that provides support. |

| Kumpfer and Hopkins (1993) | Have good intellectual competence, capacity for introspection, high self-esteem, sense of direction or mission, be an empathetic and persevering person. | The authors make reference to the fact that, in the presence of the right conditions, the environment can promote resilience. |

| Benson (1997) | Internal developmental values: having educational commitment (internal motivation to learn), positive values (being caring, honest, responsible and upright), and social competence and positive identity (high self-esteem, internal locus of control and problem-solving skills). | External developmental values: receiving support (family, neighbors, school), knowing limits and expectations, and finding a constructive use of time. |

| Grotberg (1995, 2003) | I am: a person most people like, generally calm and well-disposed, someone who plans for the future and achieves what he or she sets out to do, a person who respects himself or herself and others. I can: generate new ideas or new ways of doing things; see a task through to completion; find humor in life and use it to reduce tension; express thoughts and feelings in communicating with others; resolve conflicts in different areas. | I have: a stable family and social environment; one or more people within my family group whom I can trust and who love me unconditionally; one or more people outside my family environment whom I can fully trust; limits on my behavior; people who encourage me to be independent; good role models; access to the health, education, security and social services I need. |

| Ungar (2003) | Self and interpersonal characteristics: having good intellectual and physical skills, a sense of self-efficacy, introspection, a positive self-image, high self-esteem, goals and aspirations, a sense of humor, creativity, empathy, self-expression, assertiveness, initiative, a sense of morality and commitment to values, and knowing how to maintain a social network by establishing meaningful relationships with others. | Family characteristics: having a quality upbringing and education, a flexible environment in which emotions are expressed, low levels of family conflict, and sufficient economic resources. Environmental and sociocultural characteristics: being socially included in a safe environment, having access to educational and leisure resources, perceiving social support, and membership in organizations. |

| Authors | Pillars of Resilience |

|---|---|

| Wolin and Wolin (1993) |

|

| Rojas (2011) |

|

| Santos (2015) |

|

| Linares (2017) |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moll Riquelme, I.; Bagur Pons, S.; Rosselló Ramon, M.R. Resilience: Conceptualization and Keys to Its Promotion in Educational Centers. Children 2022, 9, 1183. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081183

Moll Riquelme I, Bagur Pons S, Rosselló Ramon MR. Resilience: Conceptualization and Keys to Its Promotion in Educational Centers. Children. 2022; 9(8):1183. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081183

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoll Riquelme, Isaac, Sara Bagur Pons, and Maria Rosa Rosselló Ramon. 2022. "Resilience: Conceptualization and Keys to Its Promotion in Educational Centers" Children 9, no. 8: 1183. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081183

APA StyleMoll Riquelme, I., Bagur Pons, S., & Rosselló Ramon, M. R. (2022). Resilience: Conceptualization and Keys to Its Promotion in Educational Centers. Children, 9(8), 1183. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081183