Parent-Reported Assessment Scores Reflect the ASD Severity Level in 2- to 7-Year-Old Children

Highlights

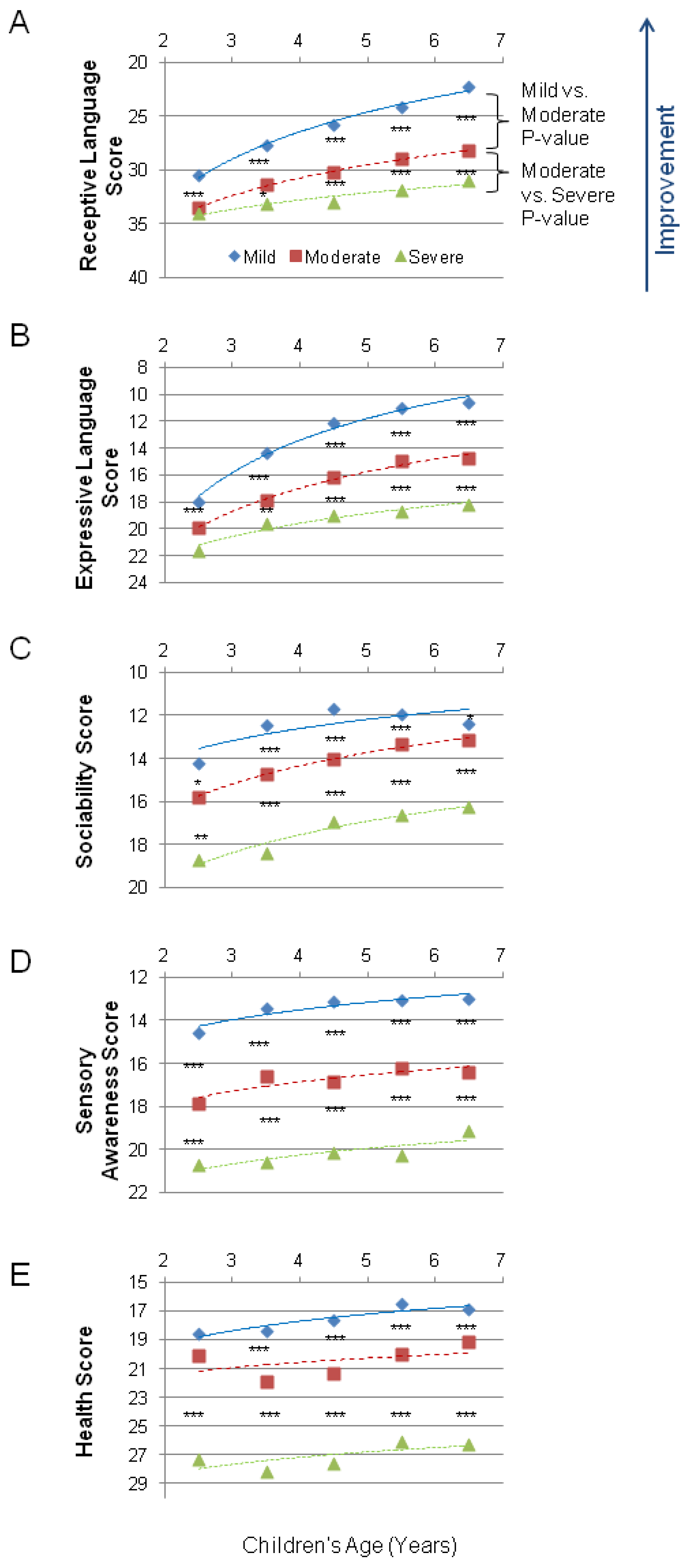

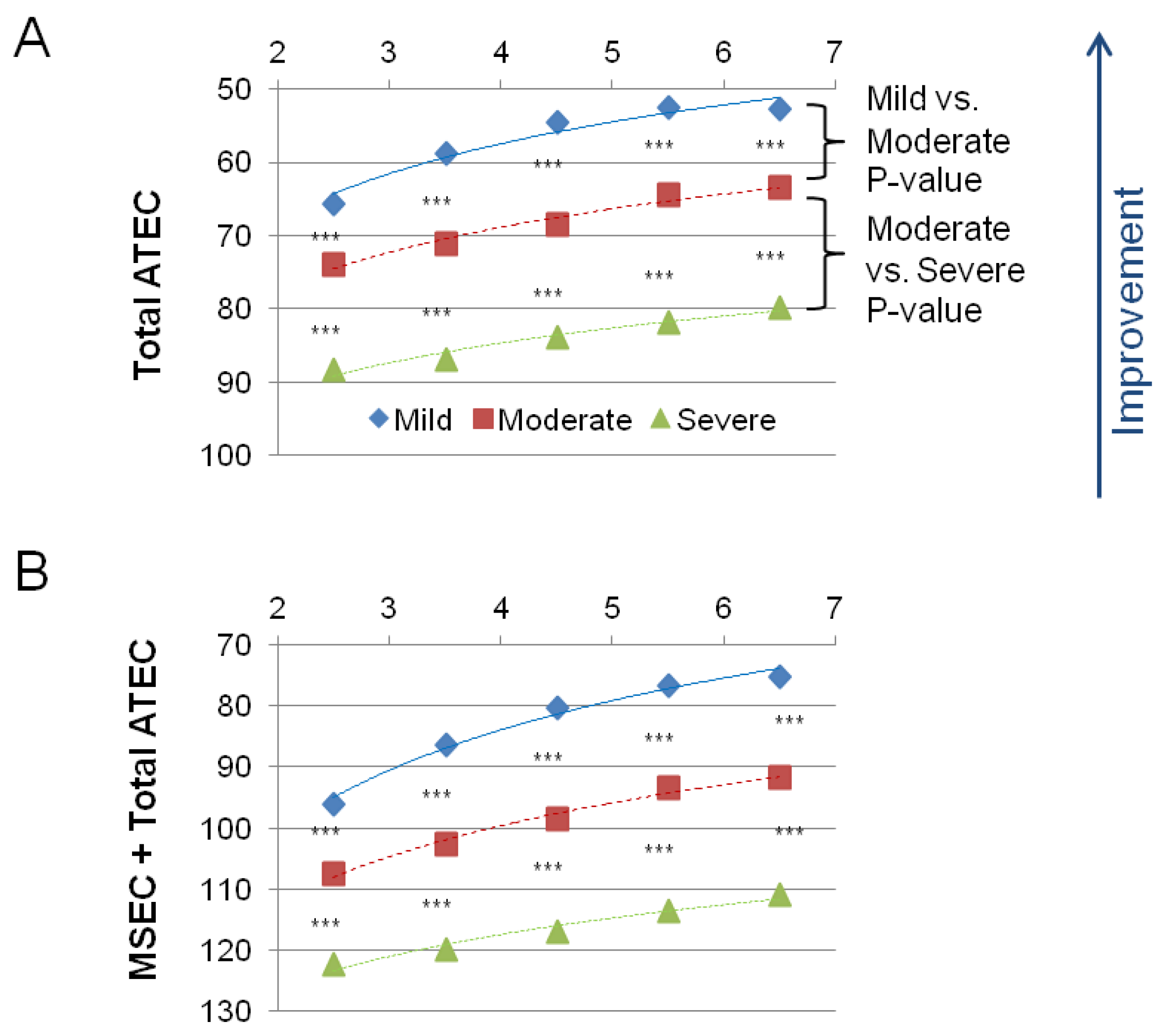

- Parent-reported assessments can reflect the severity level of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children aged 2 to 7 years.

- The study used the Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) and Mental Synthesis Evaluation Checklist (MSEC) to evaluate 9573 children with ASD.

- Scores on all five subscales (combinatorial receptive language, expressive language, sociability, sensory awareness, and health) improved with age.

- There were significant differences in scores between mild and moderate ASD and moderate and severe ASD in each subscale and in every age group of children 3 years and older.

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Assessments

2.3. Combinatorial Receptive Language Assessment

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sikich, L.; Kolevzon, A.; King, B.H.; McDougle, C.J.; Sanders, K.B.; Kim, S.-J.; Spanos, M.; Chandrasekhar, T.; Trelles, M.P.; Rockhill, C.M. Intranasal Oxytocin in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.J.; Drahota, A.; Sze, K.; Van Dyke, M.; Decker, K.; Fujii, C.; Bahng, C.; Renno, P.; Hwang, W.-C.; Spiker, M. Brief report: Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on parent-reported autism symptoms in school-age children with high-functioning autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 1608–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bellini, S. Social skill deficits and anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Dev. Disabil. 2004, 19, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarver, J.; Palmer, M.; Webb, S.; Scott, S.; Slonims, V.; Simonoff, E.; Charman, T. Child and parent outcomes following parent interventions for child emotional and behavioral problems in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism 2019, 23, 1630–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiser, C.; Morse, R. Quality-of-life measures in chronic diseases of childhood. Health Technol. Assess. Winch. Engl. 2001, 5, 1–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyshedskiy, A.; Dunn, R. Mental Imagery Therapy for Autism (MITA)-An Early Intervention Computerized Brain Training Program for Children with ASD. Autism Open Access 2015, 5, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Vyshedskiy, A.; Khokhlovich, E.; Dunn, R.; Faisman, A.; Elgart, J.; Lokshina, L.; Gankin, Y.; Ostrovsky, S.; deTorres, L.; Edelson, S.M. Novel prefrontal synthesis intervention improves language in children with autism. Healthcare 2020, 8, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.; Elgart, J.; Lokshina, L.; Faisman, A.; Khokhlovich, E.; Gankin, Y.; Vyshedskiy, A. Comparison of performance on verbal and nonverbal multiple-cue responding tasks in children with ASD. Autism Open Access 2017, 7, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunn, R.; Elgart, J.; Lokshina, L.; Faisman, A.; Waslick, M.; Gankin, Y.; Vyshedskiy, A. Tablet-Based Cognitive Exercises as an Early Parent-Administered Intervention Tool for Toddlers with Autism—Evidence from a Field Study. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.; Elgart, J.; Lokshina, L.; Faisman, A.; Khokhlovich, E.; Gankin, Y.; Vyshedskiy, A. Children With Autism Appear To Benefit From Parent-Administered Computerized Cognitive And Language Exercises Independent Of the Child’s Age Or Autism Severity. Autism Open Access 2017, 7, 1000217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimland, B.; Edelson, S. Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC); Autism Research Institute: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Braverman, J.; Dunn, R.; Vyshedskiy, A. Development of the Mental Synthesis Evaluation Checklist (MSEC): A Parent-Report Tool for Mental Synthesis Ability Assessment in Children with Language Delay. Children 2018, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fridberg, E.; Khokhlovich, E.; Vyshedskiy, A. Watching Videos and Television Is Related to a Lower Development of Complex Language Comprehension in Young Children with Autism. Healthcare 2021, 9, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, P.; Edward, E.; Vyshedskiy, A. Effect of seizures on developmental trajectories in children with autism. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.; Khokhlovich, E.; Vyshedskiy, A. Sleep problems effect on developmental trajectories in children with autism. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyshedskiy, A.; DuBois, M.; Mugford, E.; Piryatinsky, I.; Radi, K.; Braverman, J.; Maslova, V. Novel Linguistic Evaluation of Prefrontal Synthesis (LEPS) test measures prefrontal synthesis acquisition in neurotypical children and predicts high-functioning versus low-functioning class assignment in individuals with autism. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2020, 11, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scattone, D.; Raggio, D.J.; May, W. Comparison of the vineland adaptive behavior scales, and the bayley scales of infant and toddler development. Psychol. Rep. 2011, 109, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M.; Vyshedskiy, A. Combinatorial language parent-report score differs significantly between typically developing children and those with Autism Spectrum Disorders. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignell, A.; Morgan, A.T.; Woolfenden, S.; Klopper, F.; May, T.; Sarkozy, V.; Williams, K. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prognosis of language outcomes for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2018, 3, 2396941518767610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gotham, K.; Pickles, A.; Lord, C. Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 39, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schopler, E.; Reichler, R.J.; Renner, B.R. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS); Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, W.; Shire, S.; Chang, Y.-C.; Kasari, C. Joint engagement is a potential mechanism leading to increased initiations of joint attention and downstream effects on language: JASPER early intervention for children with ASD. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, K.D. Convergence between parent report and direct assessment of language and attention in culturally and linguistically diverse children. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Association, W.M. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar]

| Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Mild ASD | 295 (73%) | 868 (78%) | 1076 (84%) | 882 (80%) | 587 (79%) |

| Moderate ASD | 242 (74%) | 914 (78%) | 1136 (76%) | 1158 (77%) | 1077 (81%) |

| Severe ASD | 82 (63%) | 186 (78%) | 314 (79%) | 332 (80%) | 424 (80%) |

| Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Mild ASD | 30.4 (7.5) | 27.7 (7.9) | 25.8 (7.7) | 24.1 (8.4) | 22.3 (9.2) |

| Moderate ASD | 33.5 (5.9) | 31.4 (6.8) | 30.1 (7.3) | 28.9 (7.5) | 28.2 (7.8) |

| Severe ASD | 34 (8) | 33.1 (8) | 33 (6.8) | 31.9 (7.5) | 31 (7.9) |

| Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Mild ASD | 18 (5.9) | 14.4 (6.7) | 12.1 (6.5) | 11 (6.2) | 10.6 (6.2) |

| Moderate ASD | 20 (5.2) | 17.8 (5.8) | 16.2 (6.2) | 14.9 (6.1) | 14.7 (5.7) |

| Severe ASD | 21.6 (5.3) | 19.6 (5.6) | 19 (5.6) | 18.7 (5.6) | 18.1 (5.7) |

| Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Mild ASD | 14.2 (7.3) | 12.4 (7.5) | 11.7 (7.3) | 11.9 (7.5) | 12.3 (7.3) |

| Moderate ASD | 15.8 (7.3) | 14.7 (7.5) | 14 (7.2) | 13.3 (6.9) | 13.1 (6.9) |

| Severe ASD | 18.7 (7.9) | 18.4 (7.7) | 16.9 (7.8) | 16.6 (8.1) | 16.3 (7.7) |

| Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Mild ASD | 14.6 (6.1) | 13.4 (6.5) | 13.1 (6.4) | 13.1 (6.8) | 13 (6.5) |

| Moderate ASD | 17.9 (5.8) | 16.6 (6.4) | 16.8 (6.6) | 16.2 (6.1) | 16.4 (6.3) |

| Severe ASD | 20.7 (6.4) | 20.6 (6.7) | 20.2 (6.2) | 20.3 (6.2) | 19.1 (6.5) |

| Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Mild ASD | 18.6 (11.8) | 18.4 (7.9) | 17.6 (11.3) | 16.5 (10.9) | 16.9 (10.5) |

| Moderate ASD | 20.1 (11.8) | 21.9 (12.4) | 21.4 (12.2) | 19.9 (11.2) | 19.2 (10.5) |

| Severe ASD | 27.3 (15.1) | 28.2 (13.9) | 27.6 (12.7) | 26 (12.8) | 26.3 (13.5) |

| Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Mild ASD | 65.6 (21.3) | 58.7 (23.3) | 54.5 (23.1) | 52.5 (23) | 52.8 (22.4) |

| Moderate ASD | 73.9 (20.6) | 71.1 (23.5) | 68.4 (24.3) | 64.5 (21.9) | 63.4 (21.2) |

| Severe ASD | 88.4 (23.9) | 86.9 (25.6) | 83.9 (23.4) | 81.8 (24.1) | 79.8 (23.7) |

| Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Mild ASD | 96 (23.6) | 86.4 (27.9) | 80.3 (27.2) | 76.6 (27.7) | 75.1 (27.7) |

| Moderate ASD | 107.4 (23) | 102.5 (26.6) | 98.6 (28.2) | 93.4 (26.1) | 91.7 (25.6) |

| Severe ASD | 122.4 (25.2) | 120 (28.8) | 116.9 (25.8) | 113.6 (26.6) | 110.8 (27.5) |

| Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Mild ASD | <70 | <65 | <61 | <58 | <58 |

| Moderate ASD | 70–81 | 65–79 | 61–76 | 58–73 | 58–72 |

| Severe ASD | 81–179 | 79–179 | 76–179 | 73–179 | 72–179 |

| Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Mild ASD | <102 | <94 | <89 | <85 | <83 |

| Moderate ASD | 102–115 | 94–111 | 89–108 | 85–104 | 83–101 |

| Severe ASD | 115–209 | 111–209 | 108–209 | 104–209 | 101–209 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jagadeesan, P.; Kabbani, A.; Vyshedskiy, A. Parent-Reported Assessment Scores Reflect the ASD Severity Level in 2- to 7-Year-Old Children. Children 2022, 9, 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9050701

Jagadeesan P, Kabbani A, Vyshedskiy A. Parent-Reported Assessment Scores Reflect the ASD Severity Level in 2- to 7-Year-Old Children. Children. 2022; 9(5):701. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9050701

Chicago/Turabian StyleJagadeesan, Priyanka, Adam Kabbani, and Andrey Vyshedskiy. 2022. "Parent-Reported Assessment Scores Reflect the ASD Severity Level in 2- to 7-Year-Old Children" Children 9, no. 5: 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9050701

APA StyleJagadeesan, P., Kabbani, A., & Vyshedskiy, A. (2022). Parent-Reported Assessment Scores Reflect the ASD Severity Level in 2- to 7-Year-Old Children. Children, 9(5), 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9050701