Models and Interventions to Promote and Support Engagement of First Nations Women with Maternal and Child Health Services: An Integrative Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Criteria

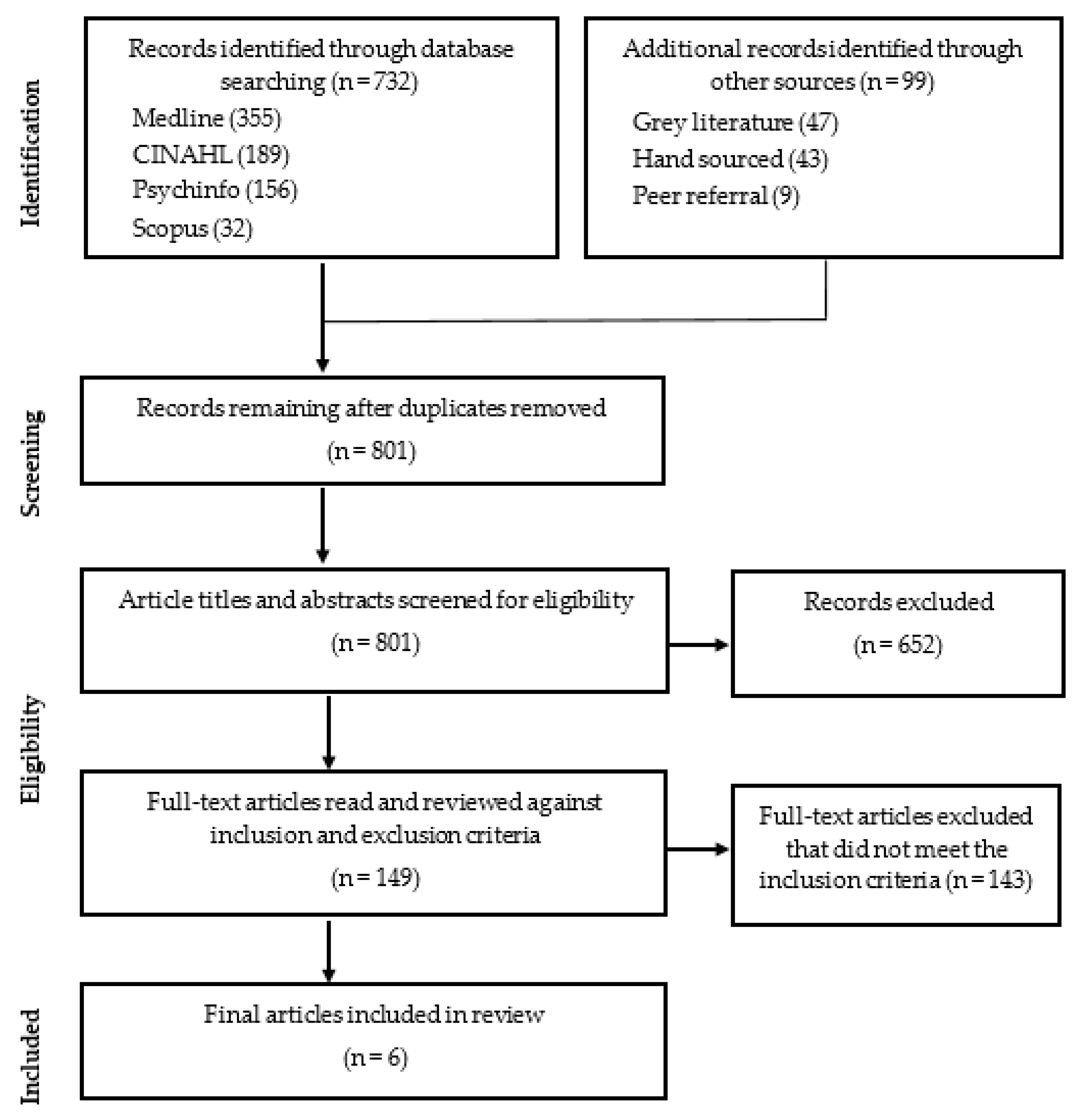

2.2. Search Strategy and Outcomes

3. Results

3.1. Enabling Factors That Influenced Access to and Engagement of First Nations Families with MCH Services

3.1.1. Timely and Appropriate Service Models or Interventions

3.1.2. Effective Integrated Community-Based Services That Are Flexible in Their Approach

3.1.3. Holistic Service Models or Interventions

3.1.4. Culturally Strong Service Models or Interventions

3.1.5. Service Models or Interventions That Encourage Earlier Identification of Risk and Need for Further Assessment, Intervention, Referral, and Support from the Antenatal Period to the Child’s Fifth Birthday (the First 2000 Days)

3.2. Barriers That Influenced Access to and Engagement of First Nations Families with MCH Services

3.2.1. Inefficient Communication Resulting in Lack of Understanding between Client and Provider

3.2.2. Cultural Differences between Client and Provider

3.2.3. Poor Continuity of Care between Services

3.2.4. Lack of Flexibility in Approach/Access to Services

3.2.5. A Model That Does Not Recognise the Importance of the Social Determinants of Health and Wellbeing

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shonkoff, J.; Phillips, D. From Neurons to Neighbourhoods: The Science of Early Child Development; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J.; Boyce, W.; McEwen, B. Neuroscience, molecular biology and the childhood roots of health disparities. JAMA 2009, 301, 2252–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belli, P.; Bustreo, F.; Preker, A. Investing in children’s health: What are the economic benefits? Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sweeny, K. The Influence of Childhood Circumstances on Adult Health; Report to the Mitchell Institute for Health and Education Policy; Victoria Institute of Strategic, Economic Studies, Victoria University: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Bank Group. Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development: A Framework for Helping Children Survive and Thrive to Transform Health and Human Potential; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Victorian Auditor-General’s Office Annual Report. Available online: https://www.data.vic.gov.au/data/dataset/vago-annual-report-2015-16 (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). General Comment No. 15 (2013) on the Right of the Child to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Art. 24), 17 April 2013, CRC/C/GC/15. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/51ef9e134.html (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Anderson, I.; Robson, B.; Connolly, M.; Al-Yaman, F.; Bjertness, E.; King, A.; Tynan, M.; Madden, R.; Bang, A.; Coimbra, C.E.A.; et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health: A population study. Lancet 2016, 388, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbold, A.; Bailie, R.; Si, D.; Dowden, M.; Kennedy, C.; Cox, R. Delivery of maternal health care in Indigenous primary care services: Baseline data for an ongoing quality improvement initiative. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smylie, J.; Adomako, P. Indigenous Children’s Health Report: Health Assessment in Action; Centre for Research on Inner City Health, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McCalman, J.; Searles, A.; Bainbridge, R.; Ham, R.; Mein, J.; Neville, J.; Campbell, S.; Tsey, K. Empowering families by engaging and relating Murri way: A Grounded Theory, study of the implementation of the Cape York Baby Basket program. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yelland, J.; Weetra, D.; Stuart-Butler, D.; Deverix, J.; Leane, C.; Kit, J.; Glover, K.; Gartland, D.; Newbury, J.; Brown, S. Primary health care for Aboriginal women and children in the year after birth: Findings from a population-based study in South Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2016, 40, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riggs, E.; Davis, E.; Gibbs, L.; Block, K.; Szwarc, J.; Casey, S.; Duell-Piening, P.; Waters, E. Accessing maternal and child health services in Melbourne, Australia: Reflections from refugee families and service providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eapen, V.; Walter, A.; Guan, J.; Descallar, J.; Axelsson, E.; Einfeld, S.; Eastwood, J.; Murphy, E.; Beasley, D.; Silove, N.; et al. The ‘Watch Me Grow’ Study Group. Maternal help-seeking for child developmental concerns: Associations with socio-demographic factors. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 53, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milroy, H.; Dudgeon, P.; Walker, R. Community life and development programs—Pathways to healing. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice; Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., Walker, R., Eds.; Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2014; pp. 419–435. [Google Scholar]

- Turley, J.; Vanek, J.; Johnston, S.; Archibald, D. Nursing role in well-child care. Systematic review of the literature. Can. Fam. Physician 2018, 64, e169–e180. [Google Scholar]

- Torraco, R. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barclay, L.; Kruske, S.; Bar-Zeev, S.; Steenkamp, M.; Josif, C.; Wulili Narjic, C.; Wardaguga, M.; Belton, S.; Gao, Y.; Dunbar, T.; et al. Improving Aboriginal maternal and infant health services in the ‘Top End’ of Australia: Synthesis of the findings of a health services research program aimed at engaging stakeholders, developing research capacity and embedding change. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Zeev, S.; Kruske, S.; Barclay, L.; Bar-Zeev, N.; Carapetis, J.; Kildea, S. Use of maternal health services by remote dwelling Aboriginal infants in tropical northern Australia: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Homer, C.; Foureur, M.; Allende, T.; Pekin, F.; Caplice, S.; Catling-Paull, C. ‘It’s more than just having a baby’ women’s experiences of a maternity service for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. Midwifery 2012, 28, e509–e515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josif, C.; Kruske, S.; Kildea, S.; Barclay, L. The quality of health services provided to remote dwelling Aboriginal infants in the top end of northern Australia following health system changes: A qualitative analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zarnowiecki, D.; Nguyen, H.; Hampton, C.; Boffa, J.; Segal, L. The Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program for Aboriginal mothers and babies: Describing client complexity and implications for program delivery. Midwifery 2018, 65, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivertsen, N.; Anikeeva, O.; Deverix, J.; Grant, J. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family access to continuity of health care services in the first 1000 days of life: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmied, V.; Kruske, S.; Barclay, L.; Fowler, C. National Framework Universal Child and Family Health Services; DoHa, A., Ed.; Australian Government: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2011.

- National Indigenous Reform Agreement (Closing the Gap). Council of Australian Governments, 2009. Available online: https://www.federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/content/npa/health/_archive/indigenous-reform/national-agreement_sept_12.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Wathen, C. The role of integrated knowledge translation in intervention research. Prev. Sci. 2018, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjortdahl, P. Ideology and reality of continuity of care. Fam. Med. 1990, 22, 361–364. [Google Scholar]

- Child Protection in Your Hands Framework. In The First 2000 Days: Conception to Age 5 Framework; NSW Ministry of Health: North Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2019.

- Fulop, N.; Allen, P. National Listening Exercise: Report of the Findings; NHS Service Delivery and Organisation National Research and Development Programme: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. The Ljubljana Charter on Reforming Healthcare. World Health Organisation, 1996. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/113302/E55363.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Jongen, C.; McCalman, J.; Bainbridge, R.; Tsey, K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander maternal and infant health and wellbeing: A systematic review of programs and services in Australian primary health care settings. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kruske, S.; Belton, S.; Wardaguga, M.; Narjic, C. Growing up our way, the first year of life in remote Aboriginal Australia. Qual. Health Rev. 2012, 22, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author/Date/Title | Sample | Type of Study/ Methodology | Thesis/ Intention of Work | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barclay, L.; Kruske, S.; Bar-Zeev, S.; Steenkamp, M.; Josif, C.; Wulili Narjic, C.; Wardaguga, M.; Belton, S.; Gao, Y.; Dunbar, T.; Kildea, S., 2014, [20]. Improving Aboriginal maternal and infant health services in the ‘Top End’ of Australia: synthesis of the findings of a health services research program aimed at engaging stakeholders, developing research capacity and embedding change. | Baseline data study: Data from 412 mothers and their 413 babies who were recruited from two remote study sites over two years (2004–2006) were audited; 120 h of observation of maternal and child health services and 60 semi-structured interviews were conducted in 3 settings with key stakeholders. Epidemiological studies: An epidemiological investigation of 7560 mothers with singleton pregnancies utilizing the Northern Territory perinatal data set that included births occurring between 2003 and 2005 was conducted. Study of out-of-hospital births: Audit of 32 records of women who birthed locally, detailed field notes, stories collected, and unstructured interviews with 7 locally birthing women and 5 of their family members. Parenting study: Longitudinal interviews and observations with 15 women from each field site from pregnancy until their babies were 12 months of age. Discussions were held with women and family members and narratives collected. Impact of colonisation of health care in the Northern Territory: An Aboriginal PhD candidate with Aboriginal co-researchers led a study of the quality and nature of health care with a case study on intergenerational learning about birthing. Post-intervention evaluation: A total of 66 participants were interviewed; the audit of the record was repeated; field notes were kept and observations undertaken in remote sites. Participatory Action Research Study: Baseline data on problems with transfer of information between the regional centre and the remote clinics led to a study by a senior manager and two researchers on improving the system. Costing study: A total of 315 mothers and singleton infants who were clients of the midwifery group practice were compared with 408 mothers with singleton pregnancies from the baseline study post-midwifery group practice intervention. Data on direct costs from the department’s perspective were collected from the first antenatal visit until 6 weeks post-partum, and data on infant costs were collected from birth to 28 days. Benchmarking of neonatal nursery admissions: Records of all 463 neonates born in 2010 and admitted to nursery were benchmarked. | A mixed-methods health services research program of work was designed, using a participatory approach. | The study consisted of two large remote Aboriginal communities in the Top End of Australia and the hospital in the regional centre that provided birth and tertiary care for these communities. The stakeholders included consumers, midwives, doctors, nurses, Aboriginal health workers, managers, policy makers, and support staff. Data were sourced from hospital and health centre records, perinatal data sets and costing data sets, observations of maternal and infant health service delivery and parenting styles, formal and informal interviews with providers and women and focus groups. Studies examined indicator sets that identify best care, the impact of quality of care and remoteness on health outcomes, discrepancies in the birth counts in a range of different data sets and ethnographic studies of ‘out of hospital’ or health-centre birth and parenting. A new model of maternity care was introduced by the health service aiming to improve care following the findings of the research. Some of these improvements introduced during the five-year research program were evaluated. | 1 + 1 = A Healthy Start to Life Project. Focus on health services in the year before and the year after birth to promote a healthy start to life. This became the main health-service-led ‘intervention’ of the study. | Overall, sustainable improvements in the maternity services for remote-dwelling Aboriginal women and their infants in the Top End of Australia occurred as a result of the midwifery group practice (MGP) intervention. These included significant improvements in maternal record keeping, antenatal care and screening, smoking cessation advice, a reduction in foetal distress in labour, and a higher proportion of women receiving postnatal contraception advice. Positive experiences of the women and MGP staff were also reported during the first year of the MGP intervention. Continuity of care, provided by appropriately qualified staff as part of the intervention, resulted in improved relationships between the midwives and their clients. The women’s engagement with other health services, facilitated by the midwives, also improved. Additionally, overall costs were reduced as a result of a significant reduction in birthing and neonatal nursery costs as a result of the MGP intervention. However, a review of this intervention conducted in 2012 showed further improvement in clinical care was still needed. Some adverse health conditions appeared to increase, possibly due to improved documentation. Specifically, unacceptable standards of infant care and parental support, no apparent consideration for the fluctuation in numbers and complexity of client cases and adequately trained staff with the required skills for providing care for children in an ‘outpatient’ model of care. Adequate coordination between remote and tertiary services was absent, which is essential to improve quality of care and reduce the risk of poor health outcomes. |

| Bar-Zeev, S.; Barclay, L.; Farrington, C.; Kildea, S., 2012, [21]. From hospital to home: the quality and safety of a postnatal discharge system used for remote dwelling Aboriginal mothers and infants in the top end of Australia. | A total of 420 women were eligible for the study, sought from 413 medical records at the regional hospital and 400 at the remote health service. A total of 66 semi-structured interviews were conducted with key health and management staff and 30 administrative staff employed in the health centres; 18 staff from the regional hospital maternity, neonatal, and paediatric units; and 12 other staff providing clinical, administrative, or logistical support for remote-dwelling women during pregnancy, around the time of birth, and during the first year of life. | Mixed-methods study, retrospective cohort study, and key informant interviews. | The study aimed to examine the transition of care in the postnatal period from a regional hospital to a remote health service and describe the quality and safety implications for remote-dwelling Aboriginal mothers and their infants. | None introduced. | This study found that there was poor discharge documentation, communication, and co-ordination between the hospital and remote health centre staff. In addition, the lack of clinical governance and a specific position holding responsibility for the postnatal discharge planning process in the hospital system were identified as serious risks to the safety of the mother and infant. |

| Homer, C.; Foureur, M.; Allende, T.; Pekin, F.; Caplice, S.; Catling-Paull, C., 2012, [22]. ‘It’s more than just having a baby’ women’s experiences of a maternity service for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. | Clinical outcomes for the 353 women who were booked with the Malabar Community Midwifery Link Service and gave birth in the 2007 and 2008 calendar years were collected prospectively from the database. | Clinical outcomes were collected prospectively and quantitatively analysed. Data from the 353 women who were booked with the Malabar Community Midwifery Link Service were transcribed and analysed qualitatively. | The paper evaluates the Malabar Community Midwifery Link Service from the perspective of Aboriginal women who accessed it. | Malabar Community Midwifery Link Service. The intervention aims to improve maternal and infant health by providing culturally appropriate care. The midwives work closely with the Aboriginal Health Education Officer and in a continuity of care model in which women get to know the midwives during the pregnancy. | Accessing the Malabar Community Midwifery Link Service helped women reduce their smoking during pregnancy. Focus group findings showed that women felt the service provided ease of access, continuity of care, and trust and trusting relationships. A total of 353 women gave birth through accessing the Malabar Community Midwifery Link Service, with forty per cent of babies identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Over ninety per cent of women had their first visit before 20 weeks of pregnancy. |

| Josif, C.; Kruske, S.; Kildea, S.; Barclay, L., 2017, [23]. The quality of health services provided to remote dwelling Aboriginal infants in the top end of northern Australia following health system changes: a qualitative analysis. | Data were collected from 25 clinicians providing or managing infant health services in the two study sites. | Semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and field notes were analysed thematically. | The study describes infant health service quality following health system changes in the area. | Health system changes. These reforms included implementation of the Healthy Under 5 Kids (HU5K) program and an education package to support staff to deliver this program. Designated Child and Family Health Nurses and Aboriginal Community Worker positions were also established in the two Healthy Start to Life study sites. | A range of factors affecting the quality of care persisted following health system changes in the two study sites. These factors included ineffective service delivery, inadequate staffing, and culturally unsafe practices. The six sub-themes identified in the data, namely, ‘very adhoc’, ‘swallowed by acute’, ‘going under’, ‘a flux’, ‘a huge barrier’, and ‘them and us’, illustrate how these factors continued following health system changes in the two study sites and, when combined, portray a ‘very chaotic system’. Improvements are needed to the quality, cultural responsiveness, and effectiveness of the health services. |

| McCalman, J.; Searles, A.; Bainbridge, R.; Ham, R.; Mein, J.; Neville, J.; Campbell, S.; Tsey, K., 2015, [11]. Empowering families by engaging and relating Murri way: a grounded theory study of the implementation of the Cape York Baby Basket program. | In-person interviews of 7 women and 3 of their family members who had received Baby Baskets were conducted. The women, aged 21 to 34 years, were either pregnant or recently pregnant and were from six of the eleven indigenous communities in Cape York, Australia. Focus groups were conducted with 18 healthcare workers. | Constructivist-grounded-theory method. | To address the region’s poor maternal and child health, the Baby Basket program was developed by Apunipima Cape York Health Council (ACYHC), a community-controlled Aboriginal health organization located in north Queensland, Australia. The program is an initiative focused on indigenous women who are expecting a baby or have recently given birth. | Apunipima Baby Basket program. Engaging and relating Murri way occurred through four strategies: connecting through practical support, creating a culturally safe practice, becoming informed and informing others, and linking at the clinic. | Overall, the Apunipima Baby Basket program intervention enabled sustainable improvements in the areas of maternal and child health. Engaging and relating Murri way occurred through four strategies: connecting through practical support, creating a culturally safe practice, becoming informed and informing others, and linking at the clinic. These strategies resulted in women and families taking responsibility for health through making healthy choices, becoming empowered health consumers, and advocating for community changes. |

| Zarnowiecki, D.; Nguyen, H.; Hampton, C.; Boffa, J.; Segal, L., 2018, [24]. The Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program for aboriginal mothers and babies: Describing client complexity and implications for program delivery. | Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program data were collected using standardised data forms by the nurses during their antenatal home visits to 276 clients from 2009 to 2015. These data were used to describe client complexity and adversity in relation to demographic and economic characteristics, mental health, and personal safety. Semi-structured interviews with 11 Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program staff and key stakeholders explored in more depth the nature of client adversity and how this affected program delivery. | Mixed-methods study using Family Partnership Program data and qualitative data collected in semi-structured interviews with Family Partnership Program staff and key stakeholders. Family Partnership Program data were used to describe the characteristics of Family Partnership Program clients. | The Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program is a home-visiting program for Aboriginal mothers and infants (pregnancy to child’s second birthday) adapted from the United States Nurse Family Partnership program. It aims to improve outcomes for Australian Aboriginal mothers and babies, and disrupt inter-generational cycles of poor health and social and economic disadvantage. The aim of this study was to describe the complexity of Program clients in the Central Australian family partnership program, understand how client complexity affects program delivery, and the implications for desirable program modification. | The Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program (ANFPP). | Most clients engaged in the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program (ANFPP) were described as ‘complicated’, with sixty-six per cent of clients experiencing four or more adversities. These adversities were found challenging for program delivery. For example, housing conditions meant that around half of all ‘home visits’ could not be conducted in the home, being held instead in staff cars or community locations. Extreme poverty, living in insecure housing, and domestic violence (almost one-third of the mothers experiencing more than two episodes of violence in 12 months) affected the delivery of program content and increased the time needed to deliver program content. Additionally, low client literacy meant written handouts were unhelpful for many, requiring the development of pictorial-based program materials. The rates of breastfeeding and child vaccination, which were higher than comparative national data for indigenous women and children in remote areas of Australia, were positive aspects of the ANFPP. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Austin, C.; Hills, D.; Cruickshank, M. Models and Interventions to Promote and Support Engagement of First Nations Women with Maternal and Child Health Services: An Integrative Literature Review. Children 2022, 9, 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9050636

Austin C, Hills D, Cruickshank M. Models and Interventions to Promote and Support Engagement of First Nations Women with Maternal and Child Health Services: An Integrative Literature Review. Children. 2022; 9(5):636. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9050636

Chicago/Turabian StyleAustin, Catherine, Danny Hills, and Mary Cruickshank. 2022. "Models and Interventions to Promote and Support Engagement of First Nations Women with Maternal and Child Health Services: An Integrative Literature Review" Children 9, no. 5: 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9050636

APA StyleAustin, C., Hills, D., & Cruickshank, M. (2022). Models and Interventions to Promote and Support Engagement of First Nations Women with Maternal and Child Health Services: An Integrative Literature Review. Children, 9(5), 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9050636