The Perceptions of Sexual Harassment among Adolescents of Four European Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

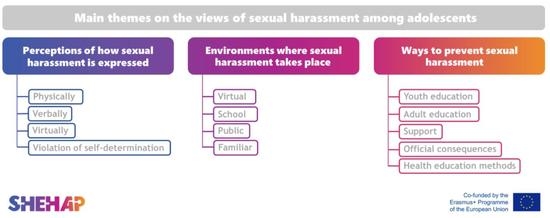

3.1. Perceptions of Sexual Harrassment

- Physically expressed sexual harassment, which included unwanted touching, physical violence, physical harassment. As participants exprssed their perception of sexual harrassment, it is:

- …touching in an unwanted way…

- …inappropriate touching…

- …touching grabbing or making other physical contact with you without consent, unwanted touching…

- …rape…violence…

- Verbally expressed sexual harassment, expreseed in different ways as commenting, spreading rumours, joking, threating, blaming. As participants explained, sexual harrassment is:

- …commenting in a sexual way about theirappearance…

- …talking about someone’s private parts…

- …slut shaming, making jokes, calling names…

- …commenting about sexual orientation…

- …making fun about sexuality…

- …making sexual gestures and telling jokes or sexual comments about someone else…

- …making someone feel bad if you don’t giving consent…

- Virtually expressed sexual harassment in terms of sending harmful material or texting. For example, as participants said:

- …sharing sexuality inappropriate images or videos…

- …someone sending me their nude photos without asking me…

- Violation of self-determination. As participants explained, this is about the actions without consent or unwanted sexual attention. For example, participants said:

- …for us sexual harassment is disrespecting people, not caring about their premission, or their position in the subjet, but in the case the subject can be their body, their sexuality, or anything like that…

- …without your permission…

- …unwanted sexual attention…

- …staring, looking at someone in an insulting, uncomfortable way…

- …share someone’s intimate information or photos without consent…

3.2. Environments That Sexual Harassment May Take Place

- Virtual environment. As particpants said in social media and the internet. As one participant said, for example:

- …it happens…on social media…the internet…

- School environment. As it was xeplained by the participants, it may take place in the school private places or there might be comments at school. For example as one of the participants described:

- …at school—someone might make inappropriate comments about the growing of the body…

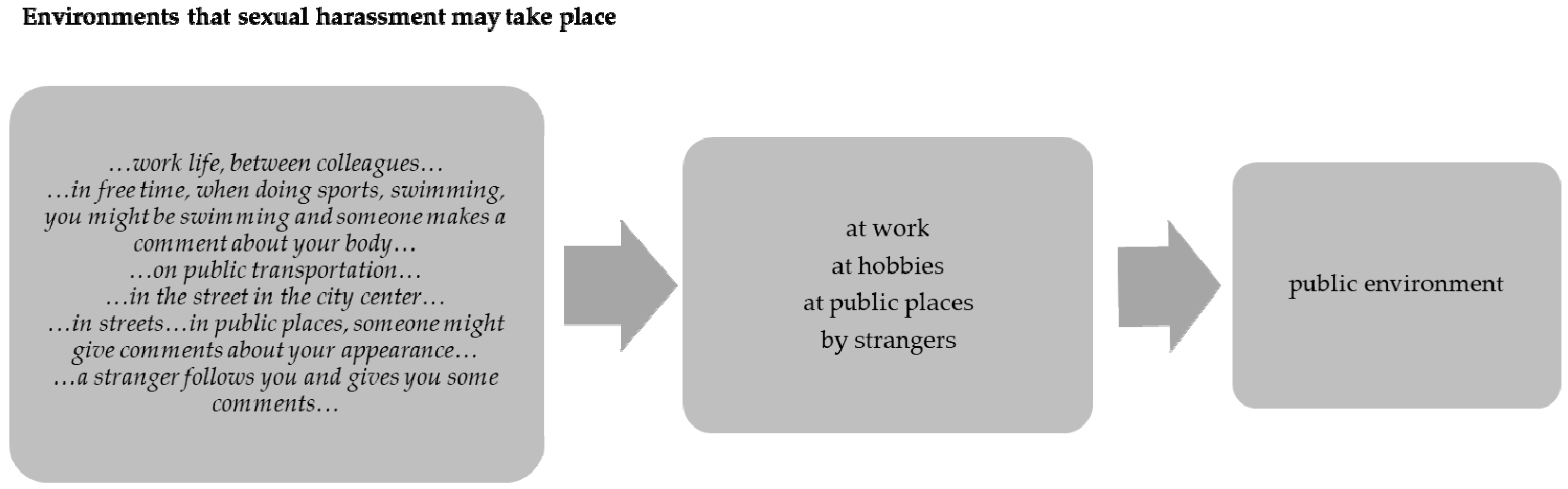

- Public environment. Participants included several situations; at work, at hobbies, at public places, by strangers. As participants said:

- …work life, betweencolleagues…

- …in free time, when doing sports, swimming, you might be swimming and someone makes a comment about your body…

- …in streets…in public places, someone might give comments about your appearance…

- …by strangers…a stranger follows you and gives you some comments…

- Familiar environment. As participants described, sexual harrassment may occur at home and among friends as well. They said:

- …at home between the parents, for example mom being harassed by dad…

- …at a friend’s house, a friend makes accomment about you…

3.3. Views on the Prevention of Sexual Harassment

- Youth education which includes awareness, health education and open discussion. As participants said:

- …educate students what is sexual harassment and what is being friendly, to recognize and distinguish those two…

- …educate where you can find the help…

- …debate the subject at school, so there is open discussion with everyone…

- Adult education which should be addressed to teachers and parents as well. As supported by the participants:

- …educate teachers about protecting kids from sexual harassment…

- …teaching parents and teachers…

- Support. This includes support received by a professional, a peer or the family. The participants

- …have a professional, such as a psychologist, so that it is easier for the victim to speak about the situation…

- …victims should see other victims and talk about and share their experience in order to support each other…

- …parents should make a comfortable atmosphere for the children…

- …need to have a very protective environment, so they won’t have a problem to discuss about this with their parents…

- Official consequences. The participants claimed that immediate action should be taken and discussion is important to address the issue of sexual harrassment. They said, for example:

- …to address the issue at the moment and not to ignore it…

- …bystanders must seek help from teachers…

- …we should face it, address it, openly discuss it and stop it at the moment it happens…

- Health education methods. The participants provided their ideas about the methods that could be used in health education on sexual harrasssment prevention. These were, digital methods, books, movies, comics.

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization; Pan American Health Organization. Understanding and Addressing Violence against Women: Intimate Partner Violence; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/77432 (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Sweeting, H.; Blake, C.; Riddell, J.; Barrett, S.; Mitchell, K.R. Sexual Harassment in Secondary School: Prevalence and Ambiguities. A Mixed Methods Study in Scottish Schools. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive 2006/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2006 on the Implementation of the Principle of Equal Opportunities and Equal Treatment of Men and Women in Matters of Employment and Occupation (Recast). 2006. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32006L0054 (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Wincentak, K.; Connolly, J.; Card, N. Teen Dating Violence: A Meta-Analytic Review of Prevalence Rates. Psychol. Violence 2017, 7, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, K.C.; Clayton, H.B.; DeGue, S.; Gilford, J.W.; Vagi, K.J.; Suarez, N.A.; Zwald, M.L.; Lowry, R. Interpersonal Violence Victimization Among High School Students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl. 2020, 69, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaszewska, P.; Schuster, I. Prevalence of teen dating violence in Europe: A systematic review of studies since 2010. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2021, 2021, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives-Cases, C.; Sanz-Barbero, B.; Ayala, A.; Pérez-Martínez, V.; Sánchez-SanSegundo, M.; Jaskulska, S.; Antunes das Neves, A.S.; Forjaz, M.J.; Pyzalski, J.; Bowes, N.; et al. Dating Violence Victimization among Adolescents in Europe: Baseline Results from the Lights4Violence Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, K. Gender-Based Violence Against Female Students in European University Settings. Int. Ann. Criminol. 2017, 55, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ståhl, S.; Dennhag, I. Online and Offline Sexual Harassment Associations of Anxiety and Depression in an Adolescent Sample. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2021, 75, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, M.B.; Pande, R.; Quresh, U. Sexual Harassment in South Asia: What Recent Data Tells us. World Bank Blogs. 2020. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/sexual-harassment-south-asia-what-recent-data-tells-us (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Zeira, A.; Astor, R.A.; Benbenishty, R. Sexual harassment in Jewish and Arab public schools in Israel. Child Abus. Negl. 2002, 26, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.J.; Ybarra, M.L.; Korchmaros, J.D. Sexual Harassment among Adolescents of Different Sexual Orientations and Gender Identities. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe Cities Free of Violence against Women and Girls Initiative. Report of the Baseline Survey Delhi. 2010. Available online: http://www.jagori.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Baseline-Survey_layout_for-Print_12_03_2011.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Duncan, N.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.; Furman, W. Sexual harassment and appearance-based peer victimization: Unique associations with emotional adjustment by gender and age. J. Adolesc. 2019, 75, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapalia, R.; Dhungana, R.R.; Adhikari, S.K.; Pandey, A.R. Understanding, Experience and Response to Sexual Harassment among the Female Students: A Mixed Method Study. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2020, 17, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, J.E.; Mumford, E.A.; Taylor, B.G. Online Sexual Harassment and Cyberbullying in a Nationally Representative Sample of Teens: Prevalence, Predictors, and Consequences. J. Adolesc. 2021, 93, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner-Cortens, D.; Eckenrode, J.; Rothman, E. Longitudinal Associations Between Teen Dating Violence Victimization and Adverse Health Outcomes. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltiala-Heino, R.; Fröjd, S.; Marttunen, M. Sexual Harassment Victimization in Adolescence: Associations with Family Background. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 56, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, C.; Pinto-Cortez, C.; Toro, E.; Efthymiadou, E.; Quayle, E. Online Sexual Harassment and Depression in Chilean Adolescents: Variations Based on Gender and Age of the Offenders. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 120, 105219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banvard-Fox, C.; Linger, M.; Paulson, D.J.; Cottrell, L.; Davidov, D.M. Sexual Assault in Adolescents. Prim. Care: Clin. Off. Pr. 2020, 47, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norcott, C.; Keenan, K.; Wroblewski, K.; Hipwell, A.; Stepp, S. The Impact of Adolescent Sexual Harassment Experiences in Predicting Sexual Risk-Taking in Young Women. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP8961–NP8973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Xing, J.; Chang, R.; Ip, P.; Fong, D.Y.-T.; Fan, S.; Ho, R.T.H.; Yip, P.S.F. Online Sexual Exposure, Cyberbullying Victimization and Suicidal Ideation among Hong Kong Adolescents: Moderating Effects of Gender and Sexual Orientation. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gea, E.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Sánchez, V. Peer Sexual Harassment in Adolescence: Dimensions of the Sexual Harassment Survey in Boys and Girls. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2016, 16, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Taylor, B.G.; Mumford, E.A. Profiles of Adolescent Relationship Abuse and Sexual Harassment: A Latent Class Analysis. Prev. Sci. 2020, 21, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roller, M.R.; Lavrakas, P.J. Applied Qualitative Research Design: A Total Quality Framework Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kabbash, I.A.; Fatehy, N.T.; Saleh, S.R.; Zidan, O.O.; Dawood, W.M. Sexual Harassment: Perception and Experience among Female College Students of Kafrelsheikh University. J. Public Health 2021, fdab294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Låftman, S.B.; Bjereld, Y.; Modin, B.; Löfstedt, P. Sexual Jokes at School and Psychological Complaints: Student- and Class-Level Associations. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 49, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulubas-Varpula, I.Z.; Björkqvist, K. Peer Aggression and Sexual Harassment among Young Adolescents in a School Context: A Comparative Study between Finland and Turkey. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 10, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işik, I.; Kulakaç, Ö. Verbal Sexual Harrassment: A Hidden Problem for Turkish Adolescent Girls. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 2015, 21, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, E.; Menckel, E. Perceptions of sexual harassment in Swedish high schools: Experiences and school-environment problems. Eur. J. Public Health 2005, 15, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.; Štulhofer, A. Online Sexual Harassment and Negative Mood in Croatian Female Adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, E.; Salazar, M.; Behar, A.I.; Agah, N.; Silverman, J.G.; Minnis, A.M.; Rusch, M.L.A.; Raj, A. Cyber Sexual Harassment: Prevalence and Association with Substance Use, Poor Mental Health, and STI History among Sexually Active Adolescent Girls. J. Adolesc. 2019, 75, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Haddon, L.; Görzig, A.; Ólafsson, K. Risks and Safety on the Internet: The Perspective of European Children: Full Findings and Policy Implications from the EU Kids Online Survey of 9-16 Year Olds and Their Parents in 25 Countries; EU Kids Online: London, UK, 2011; Available online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/33731/1/Risks%20and%20safety%20on%20the%20internet%28lsero%29.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Hand, J.Z.; Sanchez, L. Badgering or Bantering? Gender Differences in Experience of, and Reactions to, Sexual Harassment among U. S. High School Students. Gend. Soc. 2000, 14, 718–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnen, S.K.; Smolak, L. The Experience of Sexual Harassment Among Grade-School Students: Early Socialization of Female Subordination? Sex Roles 2000, 43, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrense-Dias, Y.; Suris, J.C.; Akre, C. “When It Deviates It Becomes Harassment, Doesn’t It?” A Qualitative Study on the Defnition of Sexting According to Adolescents and Young Adults, Parents, and Teachers. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 2357–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamoyi, J.; Ranganathan, M.; Mugunga, S.; Stöckl, H. Male and Female Conceptualizations of Sexual Harassment in Tanzania: The Role of Consent, Male Power, and Social Norms. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 37, 08862605211028309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lijster, G.P.A.; Kok, G.; Kocken, P.L. Preventing Adolescent Sexual Harassment: Evaluating the Planning Process in Two School-Based Interventions Using the Intervention Mapping Framework. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton-Giachritsis, C.; Hanson, E.; Whittle, H.; Beech, A. “Everyone Deserves to Be Happy and Safe”: A Mixed Methods Study Exploring How Online and Offline Child Sexual Abuse Impact Young People and How Professionals Respond to It (PDF). London: NSPCC. 2017. Available online: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/2017/impact-online-offline-child-sexual-abuse (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Karami, A.; Spinel, M.Y.; White, C.N.; Ford, K.; Swan, S. A Systematic Literature Review of Sexual Harassment Studies with Text Mining. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshetu, E. Assessment of Sexual Harassment and Associated Factors Among Grade 9-12 Female Students at Schools in Ambo District, Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia. J. Pregnancy Child Health 2015, 2, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-S.; Tzeng, Y.-L.; Teng, Y.-K. Sexual Harassment Experiences, Knowledge, and Coping Behaviors of Nursing Students in Taiwan During Clinical Practicum. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oni, H.T.; Tshitangano, T.G.; Akinsola, H.A. Sexual harassment and victimization of students: A case study of a higher education institution in South Africa. Afr. Health Sci. 2019, 19, 1478–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasting, K.; Chroni, S.; Hervik, S.E.; Knorre, N. Sexual Harassment in Sport toward Females in Three European Countries. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2011, 46, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, T.M.; Simbar, M.; Kariman, N.; Bazzazian, S.; Ghiasvand, M.; Hajiesmaello, M.; Kazemi, S. Methods for Prevention of Sexual Abuse among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Iran. J. Public Health 2020, 49, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apell, S.; Marttunen, M.; Fröjd, S.; Kaltiala, R. Experiences of Sexual Harassment Are Associated with High Self-Esteem and Social Anxiety among Adolescent Girls. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2019, 73, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menning, C.; Holtzam, M. Combining Primary Prevention and Risk Reduction Approaches in Sexual Assault Protection Programming. J. Am. Coll. Health 2005, 63, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocchi, M.; Omondi, B.; Langat, N.; Sinclair, J.B.; Pavia, L.; Mulinge, M.; Oscar Githua, O.; Neville, H.G.; Sarnquist, C. A Behavior-Based Intervention That Prevents Sexual Assault: The Results of a Matched-Pairs, Cluster-Randomized Study in Nairobi, Kenya. Prev. Sci. 2017, 18, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtele, S.K.; Kenny, M.C. Partnering with Parents to Prevent Childhood Sexual Abuse. Child Abus. Rev. 2010, 19, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.S.; Biefeld, S.D.; Bulin, J. High School Policies about Sexual Harassment: What’s on the Books and What Students Think. J. Soc. Issues 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaraman, L.; Jones, A.E.; Stein, N.; Espelage, D.L. Is It Bullying or Sexual Harassment? Knowledge, Attitudes, and Professional Development Experiences of Middle School Staff. J. Sch. Health 2013, 83, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Ameele, S.; Keygnaert, I.; Rachidi, A.; Roelens, K.; Temmerman, M. The role of the healthcare sector in the prevention of sexual violence against sub-Saharan transmigrants in Morocco: A study of knowledge, attitudes and practices of healthcare workers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuigan, W.M.; Katzev, A.R.; Pratt, C.C. Multi-level determinants of retention in a home-visiting child abuse prevention program. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, K.C.; DeGue, S.; Jones, K.; Freire, K.; Dills, J.; Smith, S.G.; Raiford, J.L. STOP SV: A Technical Package to Prevent Sexual Violence; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/sv-prevention-technical-package.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sakellari, E.; Berglund, M.; Santala, E.; Bacatum, C.M.J.; Sousa, J.E.X.F.; Aarnio, H.; Kubiliutė, L.; Prapas, C.; Lagiou, A. The Perceptions of Sexual Harassment among Adolescents of Four European Countries. Children 2022, 9, 1551. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9101551

Sakellari E, Berglund M, Santala E, Bacatum CMJ, Sousa JEXF, Aarnio H, Kubiliutė L, Prapas C, Lagiou A. The Perceptions of Sexual Harassment among Adolescents of Four European Countries. Children. 2022; 9(10):1551. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9101551

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakellari, Evanthia, Mari Berglund, Elina Santala, Claudia Mariana Juliao Bacatum, Jose Edmundo Xavier Furtado Sousa, Heli Aarnio, Laura Kubiliutė, Christos Prapas, and Areti Lagiou. 2022. "The Perceptions of Sexual Harassment among Adolescents of Four European Countries" Children 9, no. 10: 1551. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9101551

APA StyleSakellari, E., Berglund, M., Santala, E., Bacatum, C. M. J., Sousa, J. E. X. F., Aarnio, H., Kubiliutė, L., Prapas, C., & Lagiou, A. (2022). The Perceptions of Sexual Harassment among Adolescents of Four European Countries. Children, 9(10), 1551. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9101551