Parenting Styles, Coparenting, and Early Child Adjustment in Separated Families with Child Physical Custody Processes Ongoing in Family Court

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Parenting and Coparenting after Divorce or Separation

1.2. Child Physical Custody

1.3. Child Sole/Joint Physical Custody, Interparental Conflict and Young Children’s Outcomes

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedures and Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives: Parenting Styles, Coparenting, and Child Adjustment

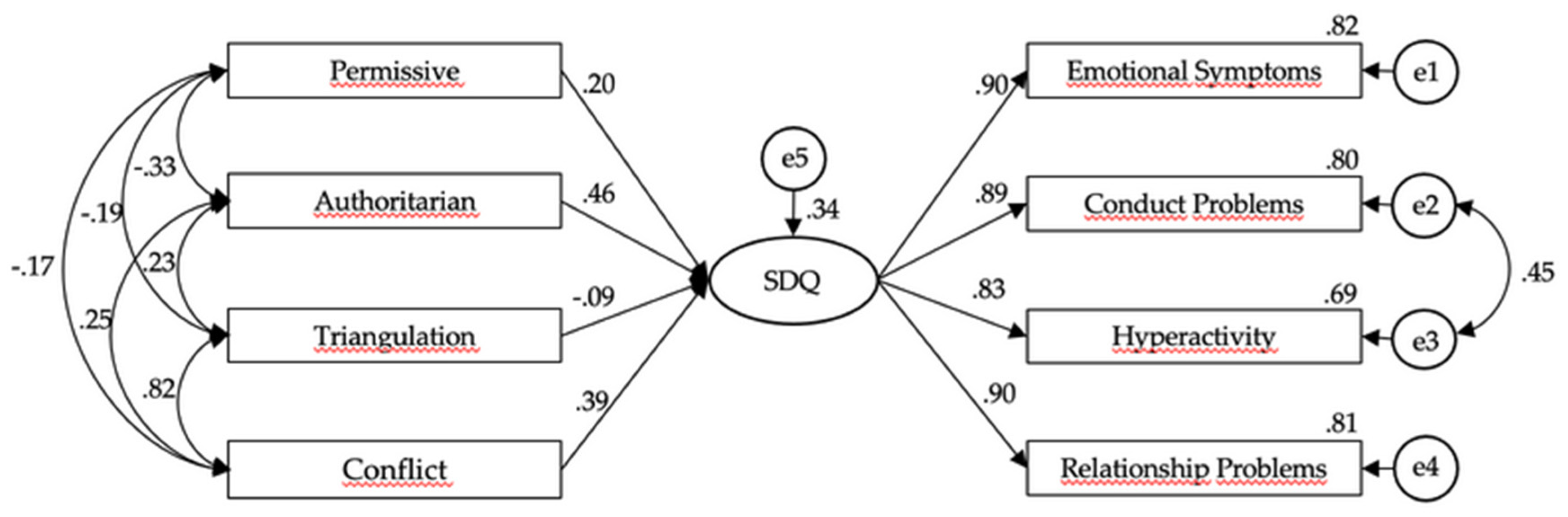

3.2. Path Analisys

3.3. Multigroup Analysis of Model Invariance

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferraro, A.J.; Davis, T.R.; Petren, R.E.; Pasley, K. Postdivorce Parenting: A Study of Recently Divorced Mothers and Fathers. J. Divorce Remarriage 2016, 57, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamela, D.; Figueiredo, B. Post-divorce representations of marital negotiation during marriage predict parenting alliance in newly divorced parents. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2011, 26, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elam, K.K.; Sandler, I.; Wolchik, S.A.; Tein, J.-Y.; Rogers, A. Latent profiles of postdivorce parenting time, conflict, and quality: Children’s adjustment associations. J. Fam. Psychol. 2019, 33, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjern, A.; Urhoj, S.; Fransson, E.; Bergström, M. Mental Health in Schoolchildren in Joint Physical Custody: A Longitudinal Study. Children 2021, 8, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, K.; Hughes, F. Parental Support Mediates the Link Between Marital Conflict and Child Internalizing Symptoms. Psi Chi J. Undergrad. Res. 2011, 16, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinquart, M.; Kauser, R. Do the associations of parenting styles with behavior problems and academic achievement vary by culture? Results from a meta-analysis. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2018, 24, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querido, J.G.; Warner, T.; Eyberg, S.M. Parenting Styles and Child Behavior in African American Families of Preschool Children. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2002, 31, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubert, D.; Pinquart, M. The Association Between Coparenting and Child Adjustment: A Meta-Analysis. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2010, 10, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, M.; Trommsdorff, G.; Muñoz, L. Children’s Self-Regulation and School Achievement in Cultural Contexts: The Role of Maternal Restrictive Control. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bastaits, K.; Ponnet, K.; Mortelmans, D. Do Divorced Fathers Matter? The Impact of Parenting Styles of Divorced Fathers on the Well-Being of the Child. J. Divorce Remarriage 2014, 55, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmuth, K.A.; Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, problematic parenting practices, and children’s symptoms of psychopathology. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 34, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijk, R.V.; Valk, I.E.; Deković, M.; Branje, S. A meta-analysis on interparental conflict, parenting, and child adjustment in divorced families: Examining mediation using meta-analytic structural equation models. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 79, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, P.R. Marital Discord, Divorce, and Children’s Well-being: Results from a 20-year longitudinal study of two generations. In Families Count: Effects on Child and Adolescent Development; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, W.G. Parental gatekeeping and child custody evaluation: Part III: Protective gatekeeping and the overnights “Co-nundrum”. J. Divorce Remarriage 2018, 59, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamela, D.; Figueiredo, B.; Bastos, A.; Feinberg, M. Typologies of Post-divorce Coparenting and Parental Well-Being, Parenting Quality and Children’s Psychological Adjustment. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016, 47, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McIntosh, J.E. Legislating for shared parenting: Exploring some underlying assumptions. Fam. Court. Rev. 2009, 47, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanassche, S.; Sodermans, A.K.; Matthijs, K.; Swicegood, G. Commuting between two parental households: The association between joint physical custody and adolescent wellbeing following divorce. J. Fam. Stud. 2013, 19, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorek, Y. Children of divorce evaluate their quality of life: The moderating effect of psychological processes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 107, 104533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalil, A.; Mogstad, M.; Rege, M.; Votruba, M. Divorced Fathers’ Proximity and Children’s Long-Run Outcomes: Evidence From Norwegian Registry Data. Demography 2011, 48, 1005–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmeyer, J.; Coleman, M.; Ganong, L.H. Postdivorce Coparenting Typologies and Children’s Adjustment. Fam. Relat. 2014, 63, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westrupp, E.M.; Rose, N.; Nicholson, J.M.; Brown, S.J. Exposure to Inter-Parental Conflict Across 10 Years of Childhood: Data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1966–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Cheung, R.Y.M.C.; Koss, K.; Davies, P. Parental Depressive Symptoms and Adolescent Adjustment: A Prospective Test of an Explanatory Model for the Role of Marital Conflict. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitzmann, K.M.; Gaylord, N.K.; Holt, A.R.; Kenny, E.D. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P. Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2002, 43, 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, E.M.; Schermerhorn, A.C.; Davies, P.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Cummings, J.S. Interparental Discord and Child Adjustment: Prospective Investigations of Emotional Security as an Explanatory Mechanism. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grych, J.H.; Fincham, F.D. Children’s Appraisals of Marital Conflict: Initial Investigations of the Cognitive-Contextual Framework. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimkowski, J.R.; Schrodt, P. Coparental Communication as a Mediator of Interparental Conflict and Young Adult Children’s Mental Well-Being. Commun. Monogr. 2012, 79, 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallman, H.M.; Ohan, J. Parenting Style, Parental Adjustment, and Co-Parental Conflict: Differential Predictors of Child Psychosocial Adjustment Following Divorce. Behav. Chang. 2016, 33, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, C.; Martinez-Torteya, C.; Bogat, G.A.; Levendosky, A.A. Child Appraisals of Interparental Conflict: The Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Parent–Child Relationship Quality. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP4919–NP4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold, G.T.; Sellers, R. Annual Research Review: Interparental conflict and youth psychopathology: An evidence review and practice focused update. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 374–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopystynska, O.; Barnett, M.A.; Curran, M.A. Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, parenting, and coparenting alliance. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 34, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pordata. Taxa Bruta de Divorcialidade [Crude Divorce Rate]. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Taxa+bruta+de+divorcialidade-651 (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Steinbach, A.; Augustijn, L. Post-Separation Parenting Time Schedules in Joint Physical Custody Arrangements. J. Marriage Fam. 2021, 83, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruijt, E.; Duindam, V. Joint Physical Custody in The Netherlands and the Well-Being of Children. J. Divorce Remarriage 2009, 51, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pampliega, A.; Herrero, M.; Cormenzana, S.; Corral, S.; Sanz, M.; Merino, L.; Iriarte, L.; De Alda, I.O.; Alcañiz, L.; Álvarez, I. Custody and Child Symptomatology in High Conflict Divorce: An Analysis of Latent Profiles. Psicothema 2021, 33, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Augustijn, L. Joint physical custody, parent–child relationships, and children’s psychosomatic problems. J. Public Health 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustijn, L. The relation between joint physical custody, interparental conflict, and children’s mental health. J. Fam. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, M.; Fransson, E.; Wells, M.B.; Köhler, L.; Hjern, A. Children with two homes: Psychological problems in relation to living arrangements in Nordic 2- to 9-year-olds. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 47, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Steinbach, A.; Augustijn, L. Children’s well-being in sole and joint physical custody families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, M.; Jesus, S.N.; Hipólito, H. Questionário de Estilos Parentais para Pais (PAQ-P)—Estudos de Validação [Parenting Styles Questionnaire-Parents Report (PAQ-P)—Validation studies], Proceedings of the Actas do XV Conferência Internacional de Avaliação Psicológica: Formas e Contextos, Lisbon, July, 2011; Sociedade Portuguesa de Psicologia: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011; pp. 760–770. [Google Scholar]

- Stadelmann, S.; Perren, S.; Groeben, M.; Von Klitzing, K. Parental Separation and Children’s Behavioral/Emotional Problems: The Impact of Parental Representations and Family Conflict. Fam. Process. 2010, 49, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dorn, O.; Schudlich, T.D.R. The enduring effects of infant emotional security in influencing preschooler adaptation to interparental conflict. In Parenting: Studies by an Ecocultural and Transactional Perspective; Benedetto, L., Ingrassia, M., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/books/parenting-studies-by-an-ecocultural-and-transactional-perspective/enduring-effects-of-infant-emotional-security-on-preschooler-adaptation-to-interparental-conflict (accessed on 7 June 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schudlich, T.D.D.R.; White, C.R.; Fleischhauer, E.A.; Fitzgerald, K.A. Observed Infant Reactions During Live Interparental Conflict. J. Marriage Fam. 2011, 73, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, L.A.; Umemura, T.; Jacobvitz, D.; Hazen, N. Marital conflict and parental responses to infant negative emotions: Relations with toddler emotional regulation. Infant Behav. Dev. 2015, 40, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schudlich, T.D.D.R.; Jessica, N.W.; Erwin, S.E.; Rishor, A. Infants’ emotional security: The confluence of parental depression, Interparental conflict, and parenting. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 63, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, M.E.; Davies, P.T. Marital Conflict and Children: An Emotional Security Perspective; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, J.E.; Smyth, B.M.; Kelaher, M. Overnight care patterns following parental separation: Associations with emotion regulation in infants and young children. J. Fam. Stud. 2013, 19, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornello, S.L.; Emery, R.; Rowen, J.; Potter, D.; Ocker, B.; Xu, Y. Overnight Custody Arrangements, Attachment, and Adjustment Among Very Young Children. J. Marriage Fam. 2013, 75, 871–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, W.F.; Landis, T.; Day, E.; Oderberg, N. Infant and toddlers and post divorce parental access: An initial exploration. J. Divorce Remarriage 1991, 16, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M.K.; Ebling, R.; Insabella, G. Critical aspects of parenting plans for young children: Interjecting data into the debate about overnights. Fam. Court. Rev. 2004, 42, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, J.E.; Pruett, M.K.; Kelly, J.B. Parental Separation and Overnight Care of Young Children, Part II: Putting Theory into Practice. Fam. Court. Rev. 2014, 52, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warshak, R.A. Night Shifts: Revisiting Blanket Restrictions on Children’s Overnights With Separated Parents. J. Divorce Remarriage 2018, 59, 282–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warshak, R.A. Blanket restrictions. Overnight contact between parents and young children. Fam. Court. Rev. 2000, 38, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biringen, Z.; Greve-Spees, J.; Howard, W.; Leigh, D.; Tanner, L.; Moore, S.; Sakoguchi, S.; Williams, L. Commentary on Warshak’s “Blanket restrictions: Overnight contact between parents and young children”. Fam. Court. Rev. 2002, 40, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenhofen, S.; Sutherland, K.; Biringen, Z. Families Experiencing Divorce: Age at Onset of Overnight Stays, Conflict, and Emotional Availability as Predictors of Child Attachment. J. Divorce Remarriage 2010, 51, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricius, W.V.; Suh, G.W. Should Infants and Toddlers Have Frequent Overnight Parenting Time With Fathers? The Policy Debate and New Data. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2017, 23, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosco, G.M.; Grych, J.H. Emotional, cognitive, and family systems mediators of children’s adjustment to interparental conflict. J. Fam. Psychol. 2008, 22, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Margolin, G.; Gordis, E.B.; John, R.S. Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2001, 15, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buri, J.R. Parental Authority Questionnaire. J. Personal. Assess. 1991, 57, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. Current patterns of parental authority. Dev. Psychol. 1971, 4, 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, M.F.; Ribeiro, M.T. Portuguese adaptation of the coparenting questionnaire: Confirmatory factor analysis, validity and reliability. Psicol. Reflect. Crit. 2015, 28, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleitlich, B.; Loureiro, M.; Fonseca, A.; Gaspar, M.F. Questionário de Capacidades e de Dificuldades (SDQ-Por) [Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire—Portuguese Version]. Available online: http://www.sdqinfo.org (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, M.; Martínez-Pampliega, A.; Alvarez, I. Family Communication, Adaptation to Divorce and Children’s Maladjustment: The Moderating Role of Coparenting. J. Fam. Commun. 2020, 20, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Children > 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children 2/3 | |||||||||

| M | 9.74 | 20.43 | 13.57 | 25.4 | 2.59 | 4.22 | 2.65 | 3.34 | |

| SD | 6.24 | 4.52 | 5.92 | 8.12 | 2.27 | 2.54 | 1.80 | 3.49 | |

| 1. Triang. | 1 | −0.410 ** | 0.914 ** | 0.379 ** | 0.678 ** | 0.656 ** | 671 ** | 0.783 ** | |

| 2. Perm. | −0.085 ** | 1 | −0.372 ** | −0.612 ** | −0.320 ** | −0.281 ** | −0.234 ** | −0.277 ** | |

| 3. Conf. | 0.905 ** | 0.006 ** | 1 | 0.343 ** | 0.710 ** | 0.647 ** | 607 ** | 0.753 ** | |

| 4. Auth. | 0.114 ** | −0.640 ** | 0.083 ** | 1 | 0.541 ** | 0.629 ** | 0.549 ** | 0.477 ** | |

| 5. RP | 0.592 ** | −0.264 ** | 0.566 ** | 0.338 ** | 1 | 0.766 ** | 0.763 ** | 0.764 ** | |

| 6. Hyp. | 0.579 ** | −0.126 ** | 0.499 ** | 0.392 ** | 0.467 ** | 1 | 0.809 ** | 0.721 ** | |

| 7. CP | 0.589 ** | −0.068 ** | 0.621 ** | 0.338 ** | 0.354 ** | 0.667 ** | 1 | 0.771 ** | |

| 8. EP | 0.664 ** | −0.307 ** | 0.653 ** | 0.467 ** | 0.556 ** | 0.697 ** | 0.689 ** | 1 | |

| M | 6.90 | 22.57 | 6.90 | 21.70 | 1.93 | 3.75 | 1.76 | 1.97 | |

| SD | 4.08 | 3.54 | 4.82 | 6.47 | 1.67 | 1.60 | 1.31 | 2.13 | |

| Models | CMIN/DF | CFI | PCFI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconstrained | 3.047 *** | 0.960 | 0.446 | 0.0477 | 0.100 |

| Measurement weights | 2.778 *** | 0.961 | 0.498 | 0.0486 | 0.093 |

| Structural weights | 2.772 *** | 0.956 | 0.563 | 0.0560 | 0.093 |

| Structural covariances | 3.148 *** | 0.930 | 0.714 | 0.1283 | 0.102 |

| Structural residuals | 3.206 *** | 0.926 | 0.728 | 0.1278 | 0.104 |

| Measurement residuals | 3.309 *** | 0.914 | 0.800 | 0.106 | |

| Saturated model | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Independence model | 24.586 *** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.1183 | 0.339 |

| Model | DF | CMIN | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assuming model unconstrained to be correct: | |||

| Measurement weights | 3 | 1.346 | 0.718 |

| Structural weights | 7 | 12.263 | 0.092 |

| Structural covariances | 17 | 56.141 | 0.000 |

| Structural residuals | 18 | 61.860 | 0.000 |

| Measurement residuals | 23 | 82.930 | 0.000 |

| Assuming model measurement weights to be correct: | |||

| Structural weights | 4 | 10.917 | 0.028 |

| Structural covariances | 14 | 54.795 | 0.000 |

| Structural residuals | 15 | 60.514 | 0.000 |

| Measurement residuals | 20 | 81.584 | 0.000 |

| Structural weights | 4 | 10.917 | 0.028 |

| Assuming model structural weights to be correct: | |||

| Structural covariances | 10 | 43.878 | 0.000 |

| Structural residuals | 11 | 49.596 | 0.000 |

| Measurement residuals | 16 | 70.667 | 0.000 |

| Assuming model structural covariances to be correct: | |||

| Structural residuals | 1 | 5.719 | 0.017 |

| Measurement residuals | 6 | 26.789 | 0.000 |

| Assuming model structural residuals to be correct: | |||

| Measurement residuals | 5 | 21.070 | 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pires, M.; Martins, M. Parenting Styles, Coparenting, and Early Child Adjustment in Separated Families with Child Physical Custody Processes Ongoing in Family Court. Children 2021, 8, 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8080629

Pires M, Martins M. Parenting Styles, Coparenting, and Early Child Adjustment in Separated Families with Child Physical Custody Processes Ongoing in Family Court. Children. 2021; 8(8):629. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8080629

Chicago/Turabian StylePires, Mónica, and Mariana Martins. 2021. "Parenting Styles, Coparenting, and Early Child Adjustment in Separated Families with Child Physical Custody Processes Ongoing in Family Court" Children 8, no. 8: 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8080629

APA StylePires, M., & Martins, M. (2021). Parenting Styles, Coparenting, and Early Child Adjustment in Separated Families with Child Physical Custody Processes Ongoing in Family Court. Children, 8(8), 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8080629