Mental Health in Schoolchildren in Joint Physical Custody: A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

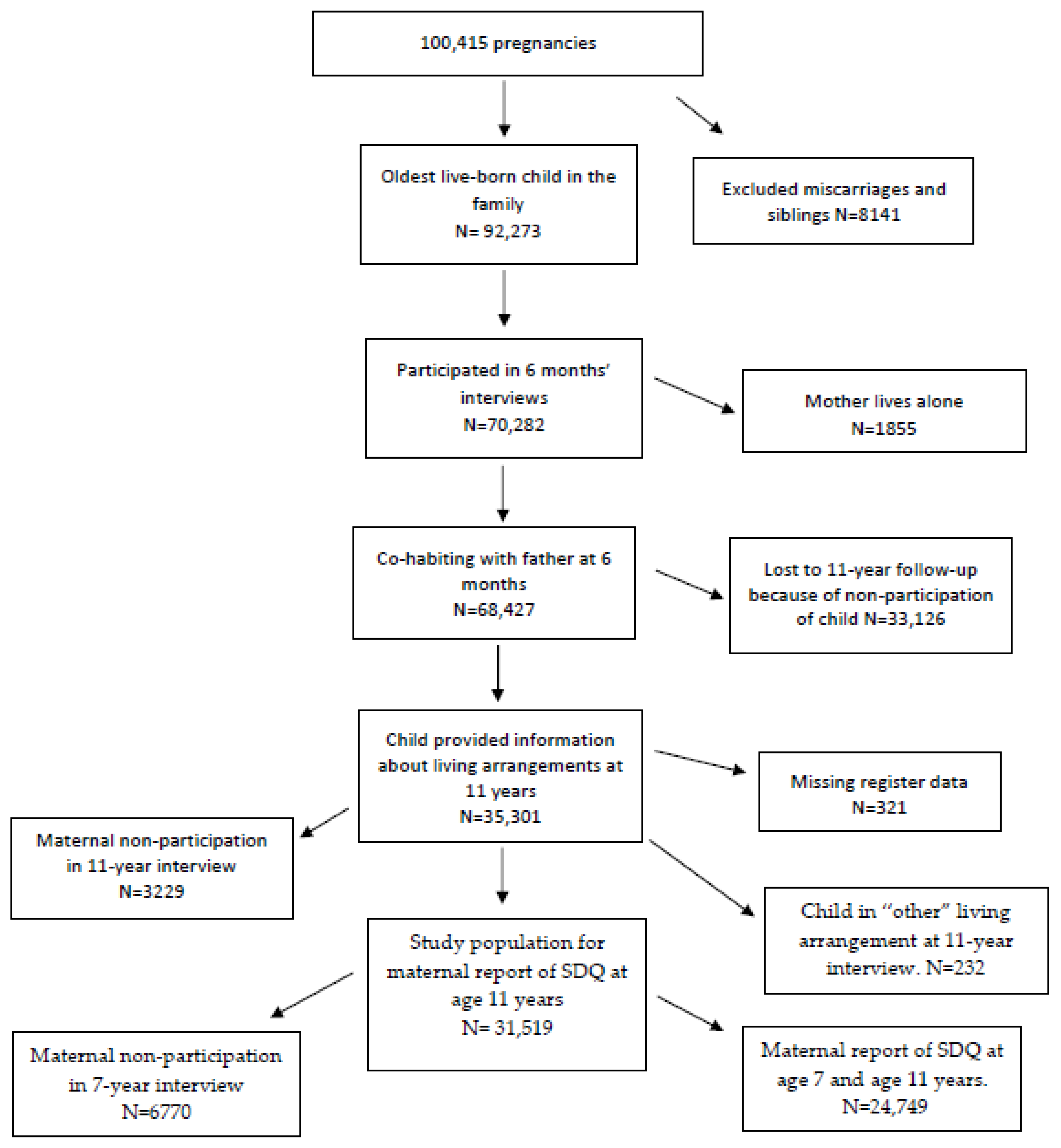

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Living Arrangements

2.2. Mental Health Outcomes

2.3. Early Childhood Indicators

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

3.2. Logistic Regression Analysis

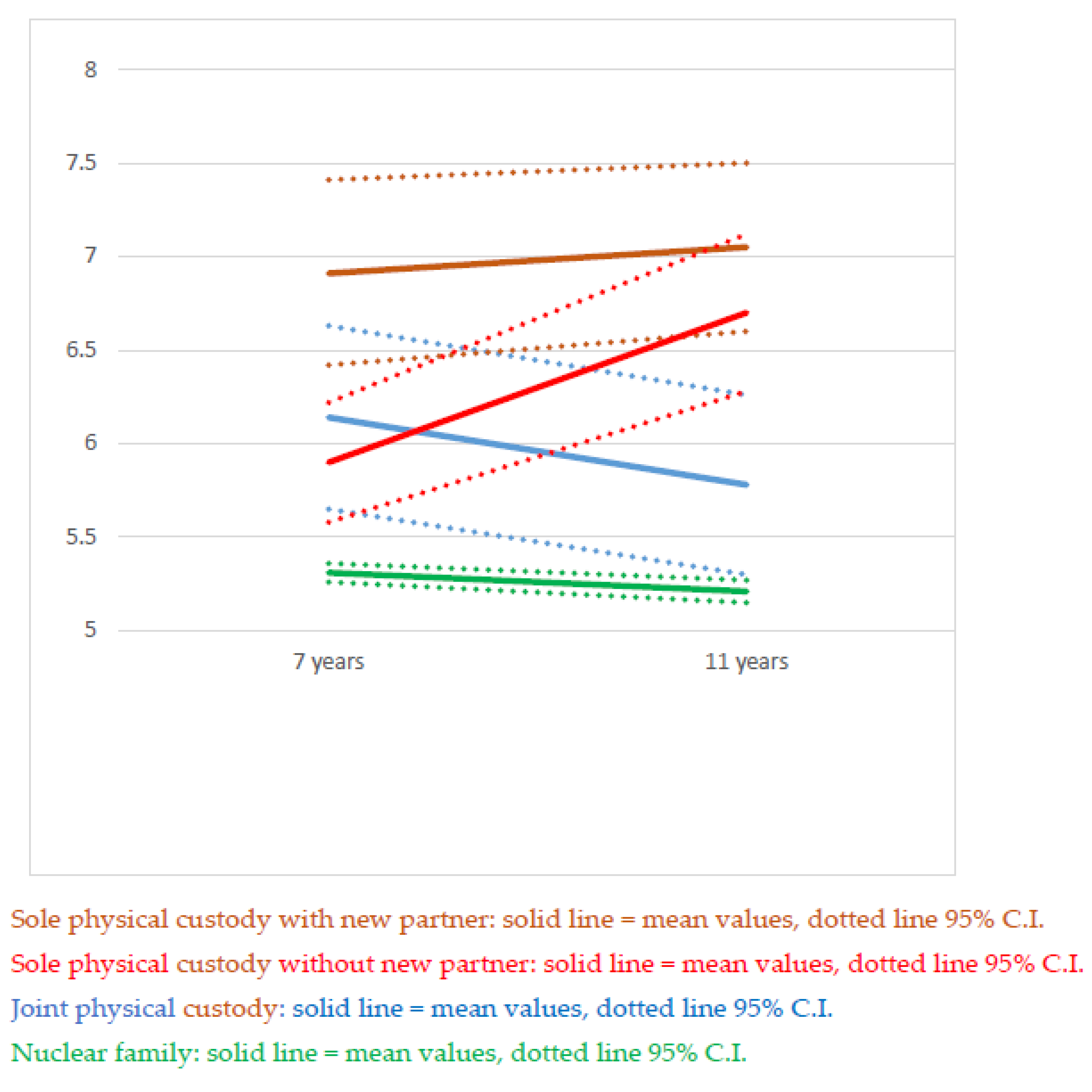

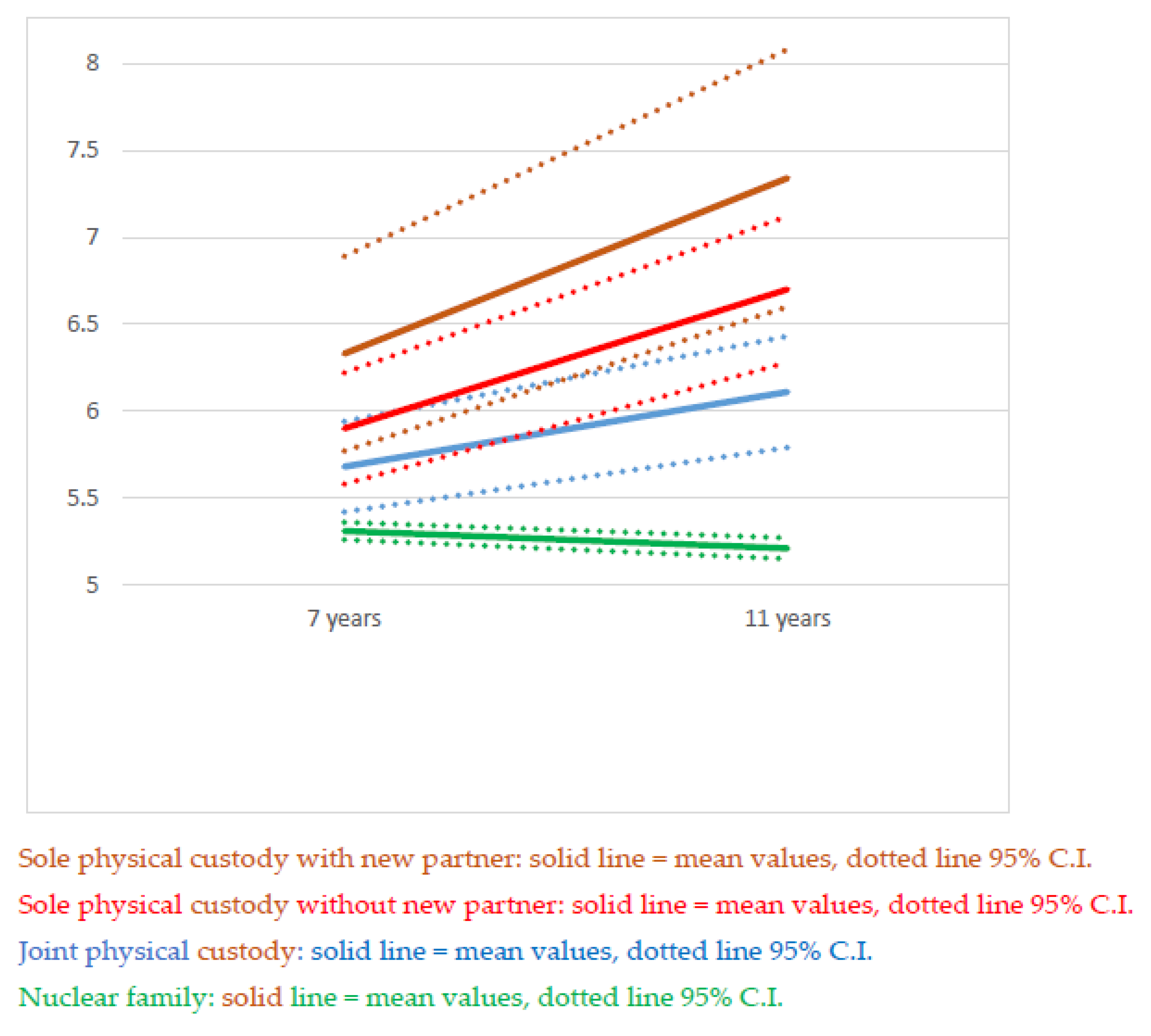

3.3. Analysis of Change between Age 7 and Age 11

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fransson, E.; Hjern, A.; Bergström, M. What can we say regarding shared parenting arrangements for Swedish children? J. Divorce Remarriage 2018, 59, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.; Schofield, T. Mediation and moderation of divorce effects on children’s behavior problems. J. Fam. Psychol. 2015, 29, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, P. The consequences of divorce for adults and children. J. Marriage Fam. 2004, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, M.; Fransson, E.; Hjern, A.; Kohler, L.; Wallby, T. Mental health in Swedish children living in joint physical custody and their parents’ life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Scand. J. Psychol. 2014, 55, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, F.; Kowaleski-Jones, L.; Menaghan, E. Paternal absence and child behavior: Does a child’s gender make a difference? J. Marriage Fam. 1997, 59, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, I.; Eydal, B.G. Parental Leave, Childcare and Gender Equality in the Nordic Countries; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, S. Contact shared residence and child well-being: Research evidence and its implications for legal decision-making. Int. J. Law Policy Fam. 2006, 20, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, J.; Chisholm, R. Cautionary notes on the shared care of children in conflicted parental separation. J. Fam. Stud. 2014, 14, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prazen, A.; Wolfinger, N.; Cahill, C.; Kowaleski-Jones, L. Joint physical custody and neighbourhood friendships in middle childhood. Sociol. Inq. 2011, 81, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baude, A.; Pearson, J.; Drapeau, S. Child adjustment in joint physical custody versus sole custody: A meta-analytic review. J. Divorce Remarriage 2016, 57, 338–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juby, H.; Marcil-Gratton, N. Sharing roles, sharing custody? Couples’ characteristics and children’s living arrangements at separation. J. Marriage Fam. 2005, 67, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, A. Children’s and parents’ well-being in joint physical custody: A literature review. Fam. Process. 2019, 58, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L. Shared physical custody: Summary of 40 studies on outcomes for children. J. Divorce Remarriage 2014, 55, 613–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkonen, J.; Bernardi, F.; Boertien, D. Family dynamics and child outcomes: An overview of research and open questions. Eur. J. Popul. 2017, 33, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribar, D. What Do Social Scientists Know about the Benefits of Marriage? A Review of Quantitative Methodologies; Institute for the Study of Labor: Bonn, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, P.R. Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 650–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 90, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.B.; Pilkington, P.D.; Ryan, S.M.; Jorm, A.F. Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 156, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbach, A.; Augustijn, L.; Corkadi, G. Joint physical custody and adolescents’ life satisfaction in 37 north american and european countries. Fam. Process. 2021, 60, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.; Melbye, M.; Olsen, S.F.; Sorensen, T.I.; Aaby, P.; Andersen, A.M.; Taxbol, D.; Hansen, K.D.; Juhl, M.; Schow, T.B.; et al. The danish national birth cohort—Its background, structure and aim. Scand. J. Public Health 2001, 29, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissing, A.S.; Dich, N.; Andersen, A.N.; Lund, R.; Rod, N.H. Parental break-ups and stress: Roles of age & family structure in 44 509 pre-adolescent children. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 829–834. [Google Scholar]

- Dreier, J.W.; Berg-Beckhoff, G.; Andersen, A.M.N.; Susser, E.; Nordentoft, M.; Strandberg-Larsen, K. Fever and infections during pregnancy and psychosis-like experiences in the offspring at age 11. A prospective study within the danish national birth cohort. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obel, C.; Heiervang, E.; Rodriguez, A.; Heyerdahl, S.; Smedje, H.; Sourander, A.; Guethmundsson, O.O.; Clench-Aas, J.; Christensen, E.; Heian, F.; et al. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire in the nordic countries. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 13, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnfred, J.; Svendsen, K.; Rask, C.; Jeppesen, P.; Fensbo, L.; Houmann, T.; Obel, C.; Niclasen, J.; Bilenberg, N. Danish norms for the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Dan. Med. J. 2019, 66, A5546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sveen, T.H.; Berg-Nielsen, T.S.; Lydersen, S.; Wichstrom, L. Detecting psychiatric disorders in preschoolers: Screening with the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjern, A.; Bergstrom, M.; Urhoj, S.K.; Andersen, A.M.N. Early childhood social determinants and family relationships predict parental separation and living arrangements thereafter. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliddal, M.; Broe, A.; Pottegard, A.; Olsen, J.; Langhoff-Roos, J. The danish medical birth register. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baadsgaard, M.; Quitzau, J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, V.M.; Rasmussen, A.W. Danish education registers. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mors, O.; Perto, G.P.; Mortensen, P.B. The danish psychiatric central research register. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanner, C.; Russell, L.; Coleman, M.; Ganong, L. Half-sibling and stepsibling relationships: A systematic integrative review. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2018, 10, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, E. Middle childhood in the context of the family. In Development during Middle Childhood: The Years from Six to Twelve to Review the Status of Basic Research on School-Age Children; Collin, W., Ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, P.R.; Keith, B. Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, R. Children’s Perspectives on Dual Residence: Everyday Life, Family Practices and Personal Relationships. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sodermans, A.; Mathijs, K.; Swicegood, G. Characteristics of joint physical custody families in flanders. Demogr. Res. 2013, 28, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laftman, S.B.; Ostberg, V. The pros and cons of social relations: An analysis of adolescents’ health complaints. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricius, W.V.; Luecken, L.J. Postdivorce living arrangements, parent conflict, and long-term physical health correlates for children of divorce. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruijt, E.; Duindam, V. Joint physical custody in the netherlands and the well-being of children. J. Divorce Remarriage 2010, 2010, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meland, E.; Breidablik, H.J.; Thuen, F. Divorce and conversational difficulties with parents: Impact on adolescent health and self-esteem. Scand. J. Public Health 2020, 48, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, R.E. Marriage, Divorce, and Children’s Adjustment, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, S.A.; Breivik, K.; Wold, B.; Bøe, T. Divorce and family structure in norway: Associations with adolescent mental health. J. Divorce Remarriage 2018, 59, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, R.; Ellis, R. Living Arrangements of Children: 2009; Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Cherlin, A. Remarriage as an incomplete institution. Am. J. Sociol. 1978, 84, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.L.; Manning, W.D.; Stykes, J.B. Family structure and child well-being: Integrating family complexity. J. Marriage Fam. 2015, 77, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, A.; Lin, I.; McLanahan, S. How hungry is the selfish gene? Econ. J. 2000, 110, 781–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L. Parenting plans for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers: Research and issues. J. Divorce Remarriage 2014, 55, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjern, A.; Bergstrom, M.; Fransso, E.; Urhoj, S.K. Living arrangements after divorce have minimal impact on mental health at age 7 years. Acta Paediatr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, P.R. Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the amato and keith (1991) meta-analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2001, 15, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, P.R.; James, S. Divorce in europe and the united states: Commonalities and differences across nations. Fam. Sci. 2010, 1, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nuclear Family | Joint Physical Custody | Sole Physical Custody with New Partner | Sole Physical Custody without New Partner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 25,468 | n = 2188 | n = 1779 | n = 2084 | |

| % | % | % | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Boys | 49.0 | 47.5 | 44.6 | 46.4 |

| Girls | 51.0 | 52.5 | 55.4 | 53.6 |

| Maternal age at birth of child | ||||

| 15–22 | 1.2 | 3.3 | 6.9 | 3.1 |

| 23–28 | 32.2 | 36.9 | 44.9 | 31.5 |

| 29–34 | 49.9 | 46.0 | 39.5 | 44.6 |

| 35+ | 16.7 | 13.8 | 8.7 | 20.8 |

| Disposable income before birth | ||||

| Quintile 1 | 14.4 | 18.3 | 25.2 | 22.1 |

| Quintile 2 | 18.9 | 18.6 | 23.5 | 22.6 |

| Quintile 3 | 20.8 | 20.1 | 21.8 | 21.5 |

| Quintile 4 | 22.6 | 21.3 | 17.3 | 18.8 |

| Quintile 5 | 23.3 | 21.7 | 12.1 | 15.0 |

| Maternal education before birth of child | ||||

| Primary | 4.2 | 4.3 | 8.4 | 8.6 |

| Secondary | 34.8 | 33.5 | 47.0 | 42.0 |

| 1–3 years post-secondary | 44.4 | 43.8 | 35.6 | 38.9 |

| 4 + years post-secondary | 16.6 | 18.4 | 8.9 | 10.5 |

| Paternal education before birth of child | ||||

| Primary only | 8.9 | 8.4 | 21.0 | 17.2 |

| Secondary | 44.0 | 42.7 | 54.5 | 50.9 |

| 1–3 years post-secondary | 28.7 | 30.5 | 17.7 | 21.1 |

| 4 + years post-secondary | 18.5 | 18.4 | 6.8 | 10.8 |

| Parental psychiatric disorder before birth of child | ||||

| Father | 3.6 | 5.3 | 10.4 | 11.5 |

| Mother | 4.2 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 7.8 |

| Mother burdened by relation to father at child age of 6 months | ||||

| No | 90.3 | 80.3 | 78.4 | 75.1 |

| Some or much | 9.7 | 19.7 | 21.6 | 24.9 |

| Mother burdened by economy at child age of 6 months | ||||

| No | 83.8 | 79.0 | 73.6 | 73.6 |

| Some or much | 16.2 | 21.0 | 26.4 | 26.4 |

| High SDQ at 11 yrs | MD in SDQ Scores 7 yrs to 11 yrs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | Beta | |

| Living arrangements at age 11 | ||||

| Nuclear family | 25,468 | 8.9 | 20,285 | −0.09 |

| Joint physical custody | 2188 | 11.7 | 1607 | 0.27 |

| Sole physical custody with a new partner | 1779 | 18.2 | 1296 | 0.32 |

| Sole physical custody without a new partner | 2084 | 17.9 | 1561 | 0.63 |

| Gender | ||||

| Boys | 15,286 | 11.7 | 12,115 | −0.04 |

| Girls | 16,233 | 8.9 | 12,634 | 0.01 |

| Maternal age at birth of child | ||||

| 15–22 | 577 | 23.6 | 426 | −0.22 |

| 23–28 | 10,454 | 11.1 | 8125 | −0.21 |

| 29–34 | 15,339 | 9.5 | 12,049 | 0.01 |

| 35+ | 5149 | 9.2 | 4149 | 0.36 |

| Disposable income before birth | ||||

| Quintile 1 | 4969 | 12.6 | 3770 | 0.08 |

| Quintile 2 | 6118 | 11.4 | 4821 | 0.06 |

| Quintile 3 | 6572 | 10.7 | 5206 | 0.06 |

| Quintile 4 | 6931 | 9.7 | 5484 | −0.04 |

| Quintile 5 | 6929 | 7.7 | 5468 | −0.14 |

| Maternal education before birth of child | ||||

| Primary | 1498 | 18.0 | 1140 | 0.33 |

| Secondary | 11,311 | 13.1 | 8764 | −0.01 |

| 1–3 years post secondary | 13,714 | 8.3 | 10,901 | −0.03 |

| 4 + years post-secondary | 4996 | 6.9 | 3949 | −0.04 |

| Paternal education before birth of child | ||||

| Primary only | 3177 | 16.4 | 2483 | 0.14 |

| Secondary | 14,164 | 11.7 | 11,064 | 0.03 |

| 1–3 years post-secondary | 8724 | 7.8 | 6914 | −0.04 |

| 4 + years post-secondary | 5454 | 6.7 | 4288 | −0.12 |

| Parental psychiatric disorder before birth of child | ||||

| Father | 1466 | 14.5 | 1121 | 0.13 |

| Mother | 1521 | 16.2 | 1151 | 0.35 |

| Mother burdened by relation to father at 6-month interview | ||||

| Some or much | 3803 | 15.9 | 2498 | 0.27 |

| Mother burdened by economy at 6-month interview | ||||

| Some or much | 5599 | 15.9 | 4298 | 0.20 |

| All | 31,513 | 10.2 | 24,749 | −0.04 |

| Model 1 1 | Model 2 2 | Model 3 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Nuclear family | 25,468 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Joint physical custody | 2188 | 1.36 (1.19–1.56) | 1.27 (1.10–1.46) | 1.25 (1.09–1.44) |

| Sole physical custody with new partner | 1779 | 2.30 (2.03–2.62) | 2.10 (1.84–2.39) | 1.63 (1.42–1.86) |

| Sole physical custody without new partner | 2084 | 2.26 (2.00–2.55) | 2.02 (1.79–2.28) | 1.72 (1.52–1.95) |

| Same Living Arrangement at 7 yrs and 11 yrs | Lived in Nuclear Family at Age 7 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 1 | Model 2 2 | Model 1 1 | Model 2 2 | |||

| Living arrangement | n | Beta (95% C.I.) | Beta (95% C.I.) | n | Beta (95% C.I.) | Beta (95% C.I.) |

| Sole physical custody without new partner | 804 | 0.45 (0.18–0.73) | 0.38 (0.10–0.65) | 739 | 0.91 (0.62–1.20) | 0.85 (0.56–1.14) |

| Sole physical custody with new partner | 383 | 0.17 (−0.22–0.56) | 0.10 (−0.30–0.49) | 286 | 1.02 (0.56–1.48) | 0.97(0.51–1.43) |

| Joint physical custody | 344 | −0.19 (−0.61–0.23) | −0.21 (−0.63–0.20) | 933 | 0.50 (0.24–0.76) | 0.47 (0.21–0.73) |

| Nuclear family | 20,137 | 1 | 1 | 20,137 | 1 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hjern, A.; Urhoj, S.K.; Fransson, E.; Bergström, M. Mental Health in Schoolchildren in Joint Physical Custody: A Longitudinal Study. Children 2021, 8, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060473

Hjern A, Urhoj SK, Fransson E, Bergström M. Mental Health in Schoolchildren in Joint Physical Custody: A Longitudinal Study. Children. 2021; 8(6):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060473

Chicago/Turabian StyleHjern, Anders, Stine Kjaer Urhoj, Emma Fransson, and Malin Bergström. 2021. "Mental Health in Schoolchildren in Joint Physical Custody: A Longitudinal Study" Children 8, no. 6: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060473

APA StyleHjern, A., Urhoj, S. K., Fransson, E., & Bergström, M. (2021). Mental Health in Schoolchildren in Joint Physical Custody: A Longitudinal Study. Children, 8(6), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060473