Needs and Experiences of Children and Adolescents with Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

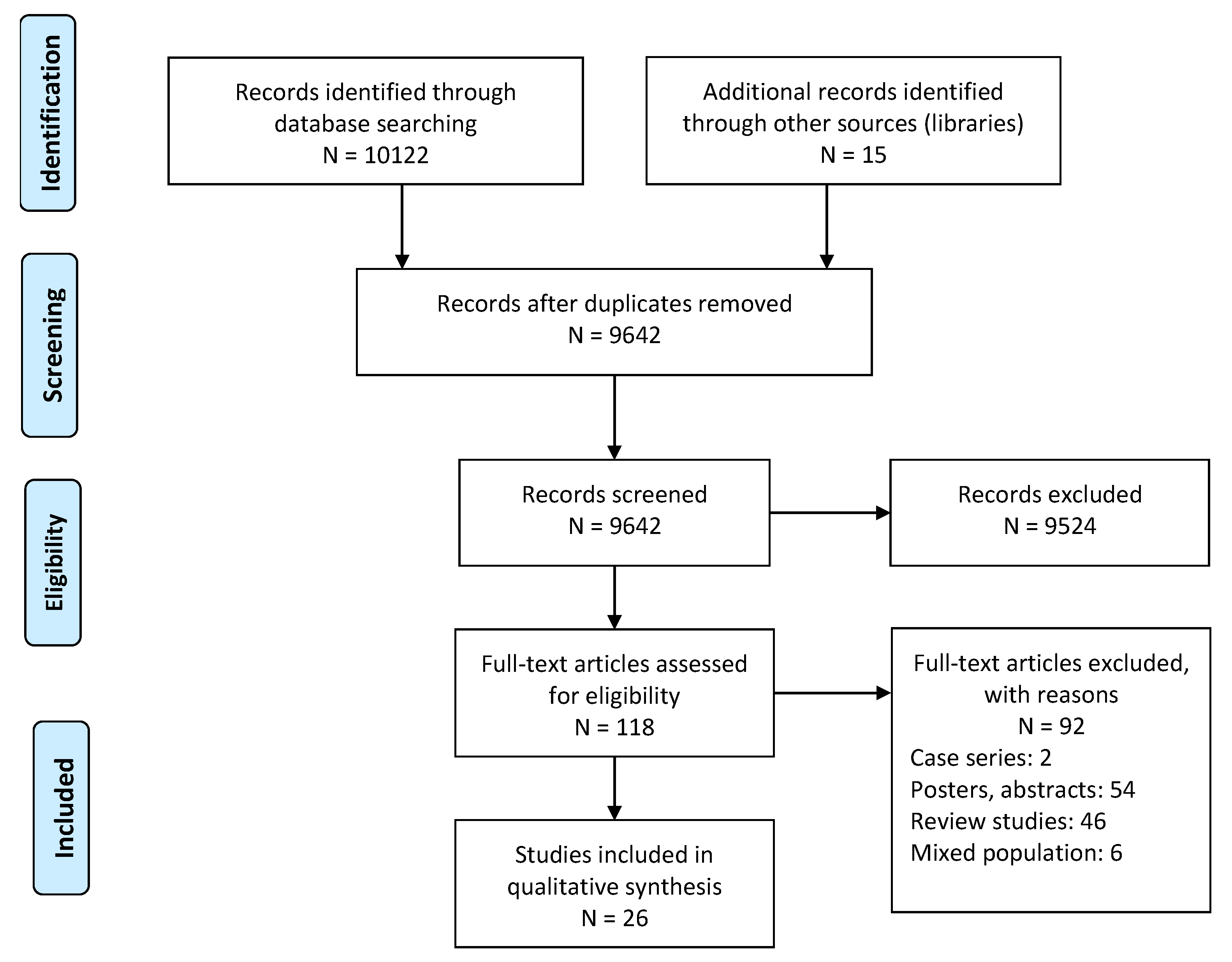

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Search Strategy

2.2. Quality Assessment

2.3. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

3.1.1. Country of Research

3.1.2. Population Characteristics

3.2. Assessment

3.3. Mixed Method Appraisal Tool

3.4. Synthesis of Findings and Grade-CERQual Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Diagnostic Phase

4.2. Physical & Psychological Impact of MS

4.3. Social Impact of MS

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bar-Or, A. Multiple sclerosis and related disorders: Evolving pathophysiologic insights. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohman, E.M.; Racke, M.K.; Raine, C.S. Multiple sclerosis—the plaque and its pathogenesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, E.A.; Chitnis, T.; Krupp, L.; Ness, J.; Chabas, D.; Kuntz, N.; Waubant, E.; US Network of Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence. Pediatric multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2009, 5, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, A.; Oleske, D.M.; Holman, J. Epidemiology of Pediatric-Onset Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Child. Neurol. 2019, 34, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghezzi, A. Pediatric multiple sclerosis: Epidemiology, clinical aspects, diagnosis and treatment. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2017, 7, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, K.; Balijepalli, C.; Desai, K.; Gullapalli, L.; Druyts, E. Epidemiology of pediatric multiple sclerosis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 44, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, T.; Pohl, D. Pediatric demyelinating disorders. Neurology 2016, 87, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Atlas of MS, 3rd ed.; The Multiple Sclerosis International Federation: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Krupp, L.B.; Tardieu, M.; Amato, M.P.; Banwell, B.; Chitnis, T.; Dale, R.C.; Ghezzi, A.; Hintzen, R.; Kornberg, A.; Pohl, D. International Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Study Group criteria for pediatric multiple sclerosis and immune-mediated central nervous system demyelinating disorders: Revisions to the 2007 definitions. Mult. Scler. J. 2013, 19, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Lowy, D.; Chitnis, T. Pathogenesis of Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis. J. Child. Neurol. 2012, 27, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, A.J.; Mowry, E.M.; Strober, J.; Waubant, E. Relapse severity and recovery in early pediatric multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2012, 18, 1008–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAllister, W.S.; Boyd, J.R.; Holland, N.J.; Milazzo, M.C.; Krupp, L.B. The psychosocial consequences of pediatric multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2007, 68, S66–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.P.; Krupp, L.B.; Charvet, L.E.; Penner, I.; Till, C. Pediatric multiple sclerosis: Cognition and mood. Neurology 2016, 87, S82–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppke, B.; Ellenberger, D.; Rosewich, H.; Friede, T.; Gärtner, J.; Huppke, P. Clinical presentation of pediatric multiple sclerosis before puberty. Eur. J. Neurol. 2014, 21, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.A.; Aubert-Broche, B.; Fetco, D.; Collins, D.L.; Arnold, D.L.; Finlayson, M.; Banwell, B.L.; Motl, R.W.; Yeh, E.A. Lower physical activity is associated with higher disease burden in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2015, 85, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banwell, B.; Ghezzi, A.; Bar-Or, A.; Mikaeloff, Y.; Tardieu, M. Multiple sclerosis in children: Clinical diagnosis, therapeutic strategies, and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2007, 6, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinay, V.; Perez Akly, M.; Zanga, G.; Ciardi, C.; Racosta, J.M. School performance as a marker of cognitive decline prior to diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2015, 21, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.; Chalder, T.; Hemingway, C.; Heyman, I.; Moss-Morris, R. “It feels like wearing a giant sandbag”. Adolescent and parent perceptions of fatigue in paediatric multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2016, 20, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- What Is A Caregiver? Available online: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/community_health/johns-hopkins-bayview/services/called_to_care/what_is_a_caregiver.html (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Maguire, R.; Maguire, P. Caregiver Burden in Multiple Sclerosis: Recent Trends and Future Directions. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzoupis, A.B.; Paparrigopoulos, T.; Soldatos, M.; Papadimitriou, G.N. The family of the multiple sclerosis patient: A psychosocial perspective. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2010, 22, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, R.; Kasilingam, E.; Kriauzaite, N. Caring for Children and Adolescents with Multiple Sclerosis. Eur. Mult. Scler. Platf. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, T.P.; Shanks, A.K.; Duffy, L.V.; Rintell, D.J. Families’ Experience of Pediatric Onset Multiple Sclerosis. J. Child. Adolesc. Trauma 2019, 12, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrie, R.A.; O’Mahony, J.; Maxwell, C.; Ling, V.; Yeh, E.A.; Arnold, D.L.; Bar-Or, A.; Banwell, B.; Canadian Pediatric Demyelinating Disease Network. Increased mental health care use by mothers of children with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2020, 94, e1040–e1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, J.; Marrie, R.A.; Laporte, A.; Bar-Or, A.; Yeh, E.A.; Brown, A.; Dilenge, M.-E.; Banwell, B. Pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis is associated with reduced parental health–related quality of life and family functioning. Mult. Scler. J. 2019, 25, 1661–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uccelli, M.M.; Traversa, S.; Trojano, M.; Viterbo, R.G.; Ghezzi, A.; Signori, A. Lack of information about multiple sclerosis in children can impact parents’ sense of competency and satisfaction within the couple. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 324, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, D.; Kirk, S. Paediatric multiple sclerosis: A qualitative study of families’ diagnosis experiences. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, D.; Kirk, S. Living with uncertainty and hope: A qualitative study exploring parents’ experiences of living with childhood multiple sclerosis. Chronic Illn. 2017, 13, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupp, L.B.; Rintell, D.; Charvet, L.E.; Milazzo, M.; Wassmer, E. Pediatric multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2016, 87, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, R.; Pluye, P.; Bartlett, G.; Macaulay, A.C.; Salsberg, J.; Jagosh, J.; Seller, R. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, S.; Booth, A.; Glenton, C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Rashidian, A.; Wainwright, M.; Bohren, M.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Colvin, C.J.; Garside, R.; et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J.R.; MacMillan, L.J. Experiences of children and adolescents living with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2005, 37, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Y.C. A Qualitative Descriptive Study Exploring the Adaptation of Families of Children with Multiple Sclerosis from the Perspective of Caregivers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, D.; Geisthardt, C.; Hoffman, H. Insights and Recommendations From Parents Receiving a Diagnosis of Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis for Their Child. J. Child. Neurol. 2019, 34, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lulu, S.; Julian, L.; Shapiro, E.; Hudson, K.; Waubant, E. Treatment adherence and transitioning youth in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2014, 3, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thannhauser, J.E. Navigating life and loss in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 1198–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, E.A.; Chiang, N.; Darshan, B.; Nejati, N.; Grover, S.A.; Schwartz, C.E.; Slater, R.; Finlayson, M.; Pediatric MS Adherence Study Group. Adherence in youth with multiple sclerosis: A qualitative assessment of habit formation, barriers, and facilitators. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 29, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, M.P.; Goretti, B.; Ghezzi, A.; Lori, S.; Zipoli, V.; Portaccio, E.; Moiola, L.; Falautano, M.; De Caro, M.F.; Lopez, M.; et al. Cognitive and psychosocial features of childhood and juvenile MS. Neurology 2008, 70, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boesen, M.S.; Blinkenberg, M.; Thygesen, L.C.; Eriksson, F.; Magyari, M. School performance, psychiatric comorbidity, and healthcare utilization in pediatric multiple sclerosis: A nationwide population-based observational study. Mult. Scler. J. 2020, 27, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretti, B.; Portaccio, E.; Ghezzi, A.; Lori, S.; Moiola, L.; Falautano, M.; Viterbo, R.; Patti, F.; Vecchio, R.; Pozzilli, C.; et al. Fatigue and its relationships with cognitive functioning and depression in paediatric multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2012, 18, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrie, R.A.; O’Mahony, J.; Maxwell, C.J.; Ling, V.; Yeh, E.A.; Arnold, D.L.; Bar-Or, A.; Banwell, B.; Canadian Pediatric Demyelinating Disease, N. High rates of health care utilization in pediatric multiple sclerosis: A Canadian population-based study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowry, E.M.; Julian, L.J.; Im-Wang, S.; Chabas, D.; Galvin, A.J.; Strober, J.B.; Waubant, E. Health-related quality of life is reduced in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Pediatr. Neurol. 2010, 43, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portaccio, E.; Simone, M.; Prestipino, E.; Bellinvia, A.; Pastò, L.; Niccolai, M.; Razzolini, L.; Fratangelo, R.; Tudisco, L.; Fonderico, M. Cognitive reserve is a determinant of social and occupational attainment in patients with pediatric and adult onset multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 42, 102145. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, E.A.; Grover, S.A.; Powell, V.E.; Alper, G.; Banwell, B.L.; Edwards, K.; Gorman, M.; Graves, J.; Lotze, T.E.; Mah, J.K. Impact of an electronic monitoring device and behavioral feedback on adherence to multiple sclerosis therapies in youth: Results of a randomized trial. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 2333–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, K.A.; Friberg, E.; Razaz, N.; Alexanderson, K.; Hillert, J. Long-term Socioeconomic Outcomes Associated With Pediatric-Onset Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzillo, R.; Chiodi, A.; Carotenuto, A.; Magri, V.; Napolitano, A.; Liuzzi, R.; Costabile, T.; Rainone, N.; Freda, M.F.; Valerio, P. Quality of life and cognitive functions in early onset multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2016, 20, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAllister, W.S.; Christodoulou, C.; Troxell, R.; Milazzo, M.; Block, P.; Preston, T.E.; Bender, H.A.; Belman, A.; Krupp, L.B. Fatigue and quality of life in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2009, 15, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, J.B.; Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Smerbeck, A.; Benedict, R.H.B.; Yeh, E.A. Fatigue and depression in children with demyelinating disorders. J. Child. Neurol. 2013, 28, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, C.E.; Grover, S.A.; Powell, V.E.; Noguera, A.; Mah, J.K.; Mar, S.; Mednick, L.; Banwell, B.L.; Alper, G.; Rensel, M.; et al. Risk factors for non-adherence to disease-modifying therapy in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2018, 24, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Atlas: Multiple Sclerosis Resources in the World 2008; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Judicibus, M.A.; McCabe, M.P. The impact of the financial costs of multiple sclerosis on quality of life. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2007, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodin, D.S.; Bates, D. Treatment of early multiple sclerosis: The value of treatment initiation after a first clinical episode. Mult. Scler. J. 2009, 15, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alroughani, R.; Boyko, A. Pediatric multiple sclerosis: A review. BMC Neurol. 2018, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.A. Involving youth with a chronic illness in decision-making: Highlighting the role of providers. Pediatrics 2018, 142, S142–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, A.A.; Graves, D.; Greenberg, B.M.; Harder, L.L. Fatigue, emotional functioning, and executive dysfunction in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Child. Neuropsychol. 2014, 20, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.-S.; Lin, S.-J.; Hsu, T.-R. Cognitive Assessment and Rehabilitation for Pediatric-Onset Multiple Sclerosis: A Scoping Review. Children 2020, 7, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiro, D.B. Early onset multiple sclerosis: A review for nurse Practitioners. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2012, 26, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pétrin, J.; Fiander, M.D.J.; Doss, P.M.I.A.; Yeh, E. A scoping review of modifiable risk factors in pediatric onset multiple sclerosis: Building for the future. Children 2018, 5, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, M.M.; Wodrich, D.L. The Effect of Sharing Health Information on Teachers’ Production of Classroom Accommodations. Psychol. Sch. 2006, 43, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofsky, D.I. The Handbook of Behavioral Medicine; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ghodusi Burojeni, M.; Heidari, M.; Neyestanak, S.; Shahbazi, S. Correlation of perceived social support and some of the demographic factors in patients with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Health Promot. Manag. 2013, 2, 6216. [Google Scholar]

- Block, P.; Rodriguez, E. Team building: An anthropologist, an occupational therapist, and the story of a pediatric multiple sclerosis community. Pract. Anthropol. 2008, 30, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Country | Design | Descriptive CAMS | CAMS Age (Years) | Time from Diagnosis (Years) | Descriptive Caregiver | Caregiver Age (Years) | Assessments | MMAT Quality | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McKay, et al. [46] | Sweden | Cohort study | CAMS: 485 (348F, 137M) Ct: 4850 (3480F, 1370M) | CAMS: 32 (26–40) Ct: 32 (26–40) | - | - | - | Education, coefficient of annual earning, disability benefits | High | Significantly lower frequency of CAMS (40.8%%) achieved postgraduate education than Ct (45.9%). Lower coefficient of annual earnings for CAMS as compared to Ct. Higher number of sick abseence and diability pension for CAMS as compared to Ct. |

| Boesen, et al. [40] | Denmark | Cohort study | CAMS: 92 (68F, 24M) Ct: 920 (-) CW-NBD: 9108 (-) | CAMS: 22 (16.2–27.3) Ct: - CW-NBD: - | 6.1 (7–9.4) | - | - | School performance (secondary/high school), psychiatric comorbidity recognized by registration at (registration at relevant healthcare centers/services), and healthcare visits (primary care centers, hospitals visits and hospital admissions) | High | No difference for school performance in CAMS, CW-NBD, and Ct. Higher rate of psychiatric comorbidity in CAMS compared to Ct and CW-NBD. Higher hazard rates for CAMS for psychopharmacological drug redemptions and out-of-hospital psychiatrist/psychologist visits compared to CW-NBD. Higher healthcare utilization in CAMS than Ct during follow-ups (30-day, 1-year, 5-year), and for primary care centers, hospitals visits and hospital admissions. Higher healthcare utilization in CAMS than CW-NBD during follow-ups (30-day, 1-year, 5-year), for hospitals visits and hospital admissions, but not for primary care centers. |

| Portaccio, et al. [44] | Italy | Cohort study | CAMS: 111 (74F, 37M) AOMS: 115 (68F, 47M) | CAMS: 15.5 ± 2.3 AOMS: 27.3 ± 8.0 | CAMS: 1.4 AOMS: 11.5 | - | - | Social status (BSMSS), work and social adjustment (WSAS), occupational complexity (Class complexity 1–4), unemployment rate, cognition (BRB test, Stroop test, NART), depression (MADRS), fatigue (FSS), and IQ | High | Lower frequency of CAMS (12%) achieved postgraduate education than AOMS (19%). Significant impact of disability on employment, dependent upon extent of disability. Higher prevalence of CAMS (13%), as compared to AOMS (5%) achieving lower educational status as compared to their parents. CAMS patients exhibited lower educational levels had lower IQ as compared to CAMS patients with higher educational levels. Cognitive impairment observed (34.5%) without differences between CAMS & AOMS. |

| Marrie, et al. [24] | Canada | Cohort study | CAMS: 222 (94F, 128M) Ct: 616 (376F, 240 M) | CAMS: 13.1 ± 5.0 Ct: 13.1 ± 5.0 | - | Mothers of CAMS: 156F Mothers of Ct: 624F | Mothers of CAMS: 29.7 ± 5.0 Mother of Ct: 29.6 ± 4.8 | Number of medical visits and prevalence of physical and mental (anxiety, mood disorder) conditions prediagnosis, diagnosis and postdiagnosis (since ±5 years of diagnosis) | High | Higher prevalence of physical conditions, mood and anxiety disorder in mothers of CAMS than Ct during pre, during and post diagnosis of their child. Higher odds of psychiatric visit for mothers of CAMS. No differences in primary care visits between mothers of CAMS or Ct. |

| Yeh, et al. [38] | Canada | Qualitative study | 28 (20F, 8M) | 16.01 ± 1.84 | - | - | - | Motivational interview regarding barriers and facilitators associated with adherence to disease modifying MS therapy | High | Adherence to medication dependent on creating and maintaining healthy habits. Barriers to adherence included: Forgetting due to disruption in routine as a result of demands from school, spending time with friends, doing extracurricular activities and travelling. Onset of fatigue reported as another prominent barrier. Emotional insecurity, including a fear of being judged, being treated differently or being embarrassed. Experience with medications, such as, negative emotional (e.g., nervousness) or physiological (e.g., pain) responses with respect to administration of medicine. Facilitators of adherence included: Remembering by using cues such as location of, maintaining a schedule, keeping up reminders, and using organizational tools like alarms and notebooks. Intrinsic motivation: Being able to manage symptoms by preventing future relapses, improvement of past symptoms, management of present symptoms, keeping health as top priority and having a desire to improve QOL Extrinsic motivation: Obeying authority (e.g., healthcare professionals), and advice especially from parents Emotional security: Receiving and providing emotional support created safe environment to build and maintain healthy medication habits. Developing awareness among peers and gaining respect of others was helpful in developing a safe space, especially for disclosing CAMS diagnosis. Experience with medications: Implementing coping strategies such as, distractions, self-motivating statements and making comparisons with worst case scenarios were sub-factors which served as a facilitator for increased adherence with medications. |

| Marrie, et al. [42] | Canada | Cohort study | CAMS: 659 (410F, 249M) Ct: 3294 (2050F, 1244M) | CAMS: 14.1 ± 4.5 Ct: 14.1 ± 4.5 | - | - | - | Hospitalization rate and number of physician visits | High | Higher odds of hospitalization and ambulatory physician visits in CAMS than Ct. Higher CAMS visits to primary care (twofold), psychiatry (threefold), ophthalmology (18-fold) and neurology (100-fold) than Ct. |

| Cross, et al. [23] | USA | Qualitative study | 21 (15F, 6M) | 14.7 | 1.6 | Parents: 21 (19F, 2M) | 43.8 | Interviews regarding symptoms prediagnosis, receiving diagnosis, adapting to life, treatment, family life, school, and living with CAMS over time | Moderate | The main themes to emerge were: Prediagnosis: Considerable stress after the onset of symptoms due to uncertainty and anxiety over possible diagnosis. Receiving the diagnosis: The presence of health care experts was helpful as they explained treatments options and prognostic outcomes. Reports regarding the information to be overwhelming was also documented. Reaction to diagnosis: Reactions included feelings of “shock”, “desperation”, “sadness”, and “fear”. Different approaches regarding disclosing diagnosis (ranging from maintaining privacy to being completely open with others). Emotional impact: Constant anxiety regarding symptoms, relapse and progression. Feelings of depression and being culpable as they felt they contributed in the development of MS through hereditary means. Treatment: Feelings of uncertainty with variations in the role of the CAMS in the decision-making process reported. Subcutaneous and intramuscular injections reported to cause anxiety or disgust in CAMS and families. Stress related to MRI associated with fear of discovery of lesions. Impact at school: Cognitive and physical symptoms caused impairments associated with learning and normal functioning. Communication regarding CAMS was a major issue and feelings of “embarrassment” reported. Family life: Extra demands due to CAMS in terms of organizing transportation, diagnostics, medications, and communicating with healthcare facilities. Negative impacts on employment, martial relationships, and sibling relationships. Positive effects also reported such as added value to family relationships after diagnosis. Multiple sclerosis community: Supports i.e., organized events, financial support, informational support by NMSS were beneficial. Concerns for future: Concerns regarding the outcome of MS in future, especially the fear of parents not being able to take care of their child, and effectiveness, costs of medications in future. |

| Hebert, et al. [35] | USA | Qualitative study | 41 (32F, 9M) | 17.6 ± 4.7 | 4.2 ± 3.2 | Parents: 42 (40F, 2M) | - | Semistructured interviews regarding children and familial experience, during diagnosis, the impact of MS on family, educational and social life, and the impact on parents hopes and concerns for future of child | High | The main themes were: Diagnosis: Large number of discrepancies in terms of diagnosis i.e., lack of knowledge or negligence reported on the behalf of physician (clinical visit before diagnosis: 3.6 ± 2.0). Parental reaction: Parents reported being “scared” and “overwhelmed”, followed by feeling “shocked”, and a “sense of relief” after initial diagnosis, attributed to lack of awareness regarding MS. |

| O’Mahony, et al. [25] | Canada | Cohort study | CAMS: 58 (39F, 19M) monoADS: 178 (81F, 97M) | CAMS: 17 monoADS: 12.6 | CAMS: 3.1 monoADS: 3.5 | Parent of CAMS: 49, Parents of child with monoADS: 149 | - | Pediatric quality of life reported by child and parents, multidimensional fatigue scale (child self-report, parent report of child’s health), and family impact module | Moderate | Poorer HrQOL for parents and CAMS in all the family impact module dimensions (compared to monoADS). No difference in HrQOL, physical and psychological wellbeing between CAMS and monoADS. Parents of CAMS reported poorer HrQOL (overall family impact score, parental emotional functioning, parental communication, parental worry, family functioning summary score, family relationships) in cases where second clinical episode (i.e., with good clinical outcome) was absent as compared to monoADS cases with full recoveries. |

| Schwartz, et al. [50] | Canada, USA | Cross sectional study | 66 (44F, 22M) | 15.4 ± 2.02 | 2.2 ± 2.2 | Parents: 132 (66F, 66M) | - | Pediatric quality of life inventory, patient reported multiple sclerosis self-efficacy scale, and multiple sclerosis treatment adherence scale | High | Poorer patient related physical functioning correlated with lower medication adherence. Better self-reported parental physical functioning correlated with enhanced medication adherence. Parents were associated with higher levels adherence of medications in CAMS with poorer pediatric QOL, school functioning, and lower multiple sclerosis self-efficacy control. Oral disease modifying therapies associated with lesser parental involvement with adherence. |

| Harris [34] | USA | Qualitative study | 20 | 17.3 ± 3.4 | 3.8 | Mother: 19F Aunt: 1F | 44.35 ± 6.60 | Interviews with caregivers of CAMS regarding their experiences with CAMS prior to diagnosis, during the diagnosis and after the diagnosis | High | Caregivers reported stressors which arose before the diagnosis of CAMS affected their perceptions of demands for caregiving. Preconceived thoughts regarding CAMS affected initial reactions to diagnosis. Those identifying resources e.g., community or spirituality for coping better adapted to diagnosis. Lack of knowledge regarding CAMS, and unstable disease progression associated with poorer adjustment. Moreover, the additional needs of CAMS influenced the adjustment and adaption of caregivers. Changes in family role due to diagnosis and additional responsibilities was reported to have a negative impact on siblings of CAMS. A lack of communication was reported in between families of CAMS regarding adjustment and adaptation approaches in CAMS. A substantial impact of the child’s health status was reported on balancing ADL. |

| Hinton and Kirk [28] | UK | Qualitative study | 23 (15F, 8M) | 15 | - | Parents: 31 (20F, 11M) | - | Semistructured interviews with parents to evaluate experiences during prediagnosis, diagnosis and postdiagnosis period. | High | Parents’ experiences associated with a feeling of “living with uncertainty”. Diagnostic uncertainty: Diagnosis process was lengthy and frightening, due to rarity of the condition and interpretation of fluctuating symptoms. Conflicts in medical opinion and a lack of definite diagnosis increased uncertainty. Daily uncertainty: Daily events defined as “unpredictable” and “uncertain”. Inability to predict outcome of disease made it difficult to manage illness along employment, familial responsibilities, social activities and normal family events. Lack of access to reliable information and professional support contributed to uncertainty. Interaction uncertainty: Disclosing child’s symptoms of MS in social interactions met with disputations. Healthy appearance of CAMS made it difficult to convince social groups as well as healthcare practitioners of the medical condition. Future uncertainty: Lack of knowledge by medical specialists created uncertainty regarding child’s future. Fear of future impairment and needs for extensive support bothered parents with worries regarding their future role. Management strategies: Information search: Searching of information (i.e., from medical practitioners, friends, family, internet, charities) post-diagnoses alleviated uncertainty. However, initial optimism was replaced by frustration when it was evident that medical specialist knowledge was limited and that the information available for undesirable and that the “anticipated sense of control was not realized”. Uncovering negative stories while searching the information increased uncertainty. Continuous monitoring: Observing, monitoring and documenting changes in child’s behavior, physical activity was also mentioned as a measure to reduce uncertainty. This was reported to allow a greater sense of control over their child’s health. Concerns regarding misinterpretation of signs increased uncertainty. Implementing changes: Modifying diet (e.g., nutritious food, Vitamin D), reduced uncertainty regarding potential relapses. However, uncertainty regarding the lasting effects of the diet on the child’s illness increased the parent’s uncertainty regarding the extent to which they can implement these changes. Optimistic thinking: Having an optimistic outlook regarding illness reduced uncertainty. The variability of symptoms and professional disputes between medical practitioners aided optimistic outcomes that their child might have been incorrectly diagnosed. Increased optimism was also aided by focusing more on the immediate present rather than the future. Some withdrew from potential sources of supports i.e., peer support groups citing they did not want to be reminded of MS. |

| Yeh, et al. [45] | Canada, USA | Cohort study | CAMS: 25 (14F, 11M) Ct: 27 (16F, 11M) | CAMS: 16.3 ± 1.8 Ct: 15.7 ± 2.5 | CAMS: 2.21 Ct: 2.58 | - | - | Adherence information from pharmacy fills, Morisky adherence, MSTAQ, parental involvement in DMT administration, PROM reflecting WOL cognitive functioning (MS neuropsychological screening assessment questionnaire), MSSE, Ryff scale of psychological well-being scale, and PDDS (Patient reported outcome of disability) | High | Reduced adherence using MEMS cap reports after three and six months’ follow-up for CAMS compared to Ct. Increased pharmacy refills reported after 6-months in CAMS compared to Ct. Reduced PEDS school function in parents of CAMS compared to parents of Ct. Enhanced Morisky adherence, self-efficacy, patient reported QOL, MSSE function and control scales in CAMS compared to Ct. Reduced MSTAQ barriers, PEDS school function, Ryff (self-acceptance, environmental mastery) well-being in CAMS as compared to Ct. |

| Carroll, et al. [18] | UK | Qualitative study | 15 (8F, 7M) | 15.2 | 2.9 | Parents: 13 (11F, 2M) | 46.8 | Semistructured interviews to evaluate the effects of fatigue on experiences of parents and their CAMS | Moderate | The themes were: Lived experience of fatigue and impact on ADL: CAMS: Feelings of physical fatigue defined as “like wearing a giant sandbag” and cognitive fatigue as “like looking through a haze”. Interference in school, social and family life reported. Specifically, disruption in memory, concentration and attention affected activities in school. Poor sleep quality also reported that gave rise to a feeling of being “wiped out”. Parents: Arranging schedule according to CAMS’s fatigue was reported to affect ADL. Uncontrollability and uncertainty of fatigue: CAMS: Fatigue perceived as being uncontrollable. Some accepted fatigue as part of the disease and a manifestation that could not be changed. Moreover, uncertainty reported with respect to deciphering differences between normal childhood fatigue and fatigue associated with CAMS. Parents: Lack of available information exacerbated uncertainty and hindered ability to manage fatigue related symptoms. Feeling of “lack of control” reported. Findings a balance: CAMS: Difficulty in finding a balance between managing working and resting. Parents: Feeling of helplessness reported. Parents less inclined to encourage CAMS with activities as they wanted to give them freedom to manage MS related fatigue themselves. Concern: CAMS: - Parents: Concerns raised regarding implications of fatigue on mental health of CAMS. Concerns regarding future ability of CAMS to manage fatigue in adulthood when the load of responsibilities would be higher. Social support and disclosure: CAMS: Disclosing diagnosis was largely met with positive supportive responses from friends. Some participants did not disclose fearing differential treatment from peers, meaning that they got overexhausted to keep up with normal ADL’s with friends. Lack of knowledge regarding the diagnosis by teachers affected misinterpretation of fatigue as “laziness” and made normal schoolwork challenging. Feelings of “guilt” reported by CAMS as they felt culpable to limit their friends. |

| Hinton and Kirk [27] | UK | Qualitative study | 21 (15F, 6M) | 15 ± 2.36 | 1.91 ± 2.25 | Parents: 23 (20F, 11M) | - | Semistructured interviews regarding the experiences of CAMS and their parents during diagnosis of MS | High | The main themes were: Symptoms: The majority developed gradual symptoms which prompted parents to seek medical advice. Recognizing a problem: CAMS reported to be reluctant to disclose symptoms. Some parents adopted a “wait and see” approach and tried to manage symptoms at home. Seeking medical advice: Continuation of symptoms or additional symptoms prompted parents to seek medical advice. Some parents reported that teacher remarks regarding the child’s health prompted them to seek medical advice. Most parents sought advice from a general practitioner at first. The influence of child’s willingness to seek medical advice was also a major factor in seeking this. Communication concern: While many (n=12) families reported being satisfied with the first healthcare consultation, others (n=11) reported being unsatisfied. Lack of tangible evidence regarding symptoms reported as one of the main concerns. Moreover, CAMS reported to feel that their concerns were disregarded without investigation. Parents were also suggested by medical practitioners to be imagining and overreacting to symptoms or even causing child’s health complaints. Medical interpretation: Frequent misinterpretation and delayed referral to secondary care frequently reported by parents. False attribution to viruses and psychosocial issues considered as the underlying reasons by healthcare practitioners. Lack of expertise to interpret MRI by pediatricians, and familiarity with CAMS reported in secondary care. Many (n=13) CAMS received an alternate diagnosis in secondary care prior to CAMS diagnosis. Questioning medical opinion: Increased frustration as a result of worsening of child’s symptoms and ignorance of medical practitioners led to feelings of “confusion” and “uncertainty” during the prediagnosis period. Parents were reported to take charge and seek secondary opinion ten consulted a different general practitioner, six requested further investigations, four presented at emergency care, and one payed for private consultation. Lack of medical knowledge or self-taught knowledge via internet search made it difficult to articulate parental concerns to medical practitioners. Uncertainty and struggles to communicate were a major cause of parental distress. Receiving a CAMS diagnosis: The time to diagnoses varied from one to 96 months after the initial onset of disease. Reluctance of pediatric neurologists to diagnose MS in childhood was reported to be a major factor for this delayed diagnosis. Moreover, uncertainty was widely reported regarding the accuracy of diagnosis due to conflicts in medical opinion, this uncertainty was also linked with “hope” for the parents that thought their child’s condition might improve. Medical practitioners which conveyed information in simple comprehensive terms while keeping in mind the emotional needs of the family were valued. |

| Lanzillo, et al. [47] | Italy | Cross sectional study | CAMS: 34 AOMS: 20 | 17.2 ± 3.6 | 3.5 ± 3.1 | - | - | Peds QOL and brief repeatable battery of neuropsychological tests | High | HrQoL reported by Peds QOL higher in CAMS as compared to AOMS. No influence of cognitive impairment was reported on the quality of life for both CAMS and AOMS. |

| Krupp, et al. [29] | USA | Qualitative study | 21 | 8–17 | - | Parents: 30 | - | Interviews | Moderate | CAMS Detrimental influences reported on physical activities and endurance. Negative impact on school performance and social relationships. Needs expressed with regards to being integrated in the consultancy phase of diagnosis. Caregivers Frustration reported at the time of diagnosis with respect to lack of knowledge and inability of medical professionals to make referrals. Some families reported sense of loss, while others reported a feeling of relief upon diagnosis. Negative impact on social relationships reported. Feelings of concern reported with respect to disease progression. Families supported the idea of including the CAMS during the phase of disclosure of diagnosis. Involvement with CAMS communities aided coping and adapting. |

| Thannhauser [37] | Canada | Qualitative study | 9 (5F, 2M) | 16–21 | - | Parents: 6 (4F, 2M) | - | Semistructured interviews of experiences with PMS during the pre- and postdiagnosis phases. | Moderate | The main themes were: Recurring loss: Onset of psychological and emotional reactions discussed with respect to initial diagnosis. An avoidance behavior was reported by few CAMS during to convey the symptoms to their caregivers. Suffering: Period of diagnosis characterized with feelings of “shock”, “confusion”, “sadness”, “frustration”, depression, “hopelessness” and” anger”. Fear of unknown: The unpredictable nature of the illness led to fear with respect to future disabilities and loss of independence. Losing trust: The prediagnosis phase of testing considered as foreign, irrelevant and confusing. A distrust in the medical system was reported, in addition to feelings of “anger” and “frustration”. Sense making: Questions over making sense of themselves in the world following diagnosis were reported. CAMS were reported to use “sense making” to question their diagnosis and why they were diagnosed with it. Carrying on: All patients were reported to eventually develop a conscious choice regarding pursuing their future with MS. Becoming me: Transformative experiences were reported by CAMS. Putting MS in its place: Acceptance of MS as a part of their life was reported by CAMS. CAMS decided to prevent MS from taking control over their present/future as they tried to avoid stigma associated with the MS. Pushing boundaries: CAMS were reported to undergo mild to moderate risk-taking behaviors which allowed them to take control over their life. Normalcy: A concept of developing, maintaining and reinventing a sense of normalcy was reported. These feelings helped them to gain control and avoid the feelings of unpredictability associated with MS. It allowed them to shift their focus away from MS to gain normalcy in ADL. The CAMS also accepted the fact that due to their condition they might have to work harder as compared to others to achieve their goals. Becoming expert: A sense of becoming an expert in their life, their body and for their medical condition was reported. This expertise was demonstrated for five main aspects: controlling symptoms, making medical decisions, managing disease knowledge, advocating for self and planning the future. Selective disclosing: Disclosing the experiences of MS was associated with a feeling of “relief”. Selective disclosure of their diagnosis, symptoms was reported for to protect their personal self, reputation, and a means to cope with emotional experiences. Judging readiness/openness to disclosure: CAMS described a process of assessing the readiness of an individual i.e., emotionally to whom the disclosure was meant to be made. Feelings of “testing waters” were reported as they wanted to protect themselves from being emotionally vulnerable. Developing cautious wisdom: A shift in mindset was reported by CAMS for others’ perception of open mindedness towards a new sense of prejudice. Meaning making: All CAMS described ways they worked towards rebuilding their own narratives regarding the self and the world. Perspective taking: A more optimistic outcome was reported by CAMS for their uncertain future, especially by means of comparing themselves with people who were worse off. A sense of compassion was also reported towards dealing with others as a result of their own condition. Reprioritizing: Increased emphasis was reportedly placed by CAMS on family, close and intimate relationships after the diagnosis. A prioritization was also reported towards a healthy lifestyle (adequate sleep, limited alcohol, increased socializing). Finding purpose: A increased desire to find a purpose in their life which was adapted to their condition was also reported by CAMS. Adopting an attitude of hope: An attitude of finding a positive perspective among their struggles and barriers was reported by CAMS. Moreover, hope was another factor that came from sources e.g., new research, being an advocate for others with MS, and by living each day. Turning points: Multiple processes were reported which influenced the CAMS’s oscillation between recurring loss and carrying on in their life. Labelling the disease: Upon diagnosis a labelling of the disease allowed the CAMS to gain a sense of control a request for supports needed to manage ADL. Shifting emotions: Strange emotions were exhibited by CAMS upon diagnosis which they reported to be overwhelming. Moreover, the disease and the medications were reported to contribute towards development of depressive mood. However, CAMS reported that with passage of time they learned to manage their emotional experiences. Managing medications: Taking medications was a major factor disrupting daily routine of CAMS. Moreover, lack of feedback regarding medication’s effectiveness affected their adherence towards treatment. Using medications was “emotionally taxing” by both CAMS and their parents. The motivation for continuing medications for the individuals arose from their friends or significant others. Dynamic relationships: Positive impact of emotional support from medical practitioners, family and friends were reported on CAMS’s ability to process their loss and carry on. Reports of social relationships ending following MS diagnosis were also reported which contributed to the experience of loss. |

| Lulu, et al. [36] | USA | Qualitative study | 30 (16F, 14M) | CAMS: 15.8 ± 2.8 | 2.5 | Parents: 30 (23F, 7M) | 46 ± 7.8 | Peds QOL, IPQ, adherence questionnaire, TRAQ, HSAQ, SES, and SDMT | High | Nonadherence rate was reported in 37% of CAMS (30% for parents). Forgetting was the most common reason for nonadherence (50% for CAMS and 33% for parents). Higher EDSS score associated with lower Peds QOL score, and lower healthcare skill. Onset of relapse was associated with lower odds of adherence. Lower Peds QOL (psychosocial aspect) for parents as compared to CAMS. Benefit of using disease modifying therapy for CAMS was reported by their parents. |

| Uccelli, et al. [26] | Italy | Cohort study | CAMS: 14 (3F, 11M) Ct: - | CAMS: 13.7 ± 1.9 Ct: - | 2.91 ± 3 | Parents of CAMS: 30 (15F, 15M) Parents Ct: 58 (29F, 29M) | Parents of CAMS: 43.1 ± 3.5 Parents Ct: 43.5 ± 5.2 | Maternal worry scale, ENRICH couple scale, WHO-five well-being index, HADS, PSOC, F-COPES, and multiple sclerosis knowledge questionnaire | Moderate | Higher depression score in HADS in parents with CAMS than Ct. Lower PSOC, and a need to seek spiritual support on F-COPES in parents with CAMS than Ct. Higher anxiety score for HADS in parents with CAMS as compared to normal parents. Lower WHO-five well-being index ENRICH score in parents with CAMS as compared to normal parents. Gender differences between groups Higher score for mothers of CAMS on the F-COPES seeking spiritual support than Ct. Higher depression score in HADS, the F-COPES seeking spiritual support for fathers of CAMS than Ct. Lower score in PSOC score, ENRICH conflict resolution subscale in fathers of CAMS as compared than Ct. Gender differences within group Significantly higher levels of ENRICH conflict resolution subscale, F-COPES total score in mothers as compared to fathers of CAMS. Higher score of multiple sclerosis knowledge questionnaire for mothers as compared to fathers of CAMS. |

| Goretti, et al. [41] | Italy | Cohort study | CAMS: 57 (31F, 26M) Ct:70 (37F, 33M) | CAMS: 16.6 ± 2.5 Ct: 16.0 ± 3.0 | 5.0 ± 3.5 | - | - | Pediatric quality of life inventory—multidimensional fatigue scale, CDI, psychiatric interview through K-SADS-PL, parent reports of fatigue and cognitive deficits | High | 21% of CAMS had depressive symptoms with CDI, and affective disorder with K-SADS-PL. Higher sleep and cognitive fatigue in CAMS than Ct. Higher general fatigue in CAMS than Ct. Higher sleep fatigue in CAMS than Ct as reported by parents. 9–14% of CAMS self-reports identified the presence of fatigue, whereas, 23–39% of parents of CAMS identified the onset of fatigue in their CAMS. Higher levels of fatigue correlated with higher scores of CDI. Higher levels of self-reported cognitive fatigue were associated with impaired problem-solving test performance. Higher levels of patient reported cognitive fatigue associated with impairments in tests of verbal learning, processing speed, complex attention and verbal comprehension. |

| Parrish, et al. [49] | USA | Cross sectional study | CAMS: 36 (25F, 11M) Ct: 92 (41F, 51M) | CAMS: 14.1 ± 3.6 Ct: 11.8 ± 3.7 | 2.1 ± 2 | - | - | Self and parent reported depression evaluated by behavior assessment system for children second edition, Varni PedsQL Multidimensional fatigue scale total (sleep, cognitive, physical) fatigue | Moderate | Parent reported: Significantly higher levels of depressive score, total fatigue, i.e., sleep-related, cognition-related and general fatigue in CAMS. CAMS reported: Significantly higher levels of total fatigue, i.e., general and cognition related fatigue. Higher levels of self-reported depressive score and sleep-related fatigue. |

| Mowry, et al. [43] | USA | Cohort study | CAMS: 41 (31F, 10M) Ct with neurological disorder: 38 (17F, 21M) Ct normal: 12 (9F, 3M) | CAMS: 14 ± 4 Ct with neurological disorder: 9 ± 5 Ct normal: 13 ± 3 | 2.0 | Parents of CAMS: 45 Parents of Ct with neurological disorder: 51 Parents of Ct normal: 10 | - | Peds QOL (child self-report, parent proxy report) | High | Lower CAMS self-reported Peds QOL (total, school, social, psychosocial, physical) than healthy controls. Lower parent proxy Peds QOL for CAMS (total, school, emotional, psychosocial, physical) than healthy controls. Higher CAMS self-reported Peds QOL (physical and social) than Ct with neurological disorders. Lower parent proxy Peds QOL for CAMS (total, physical, psychosocial, and social) than Ct with neurological disorders. |

| MacAllister, et al. [48] | USA | Cross sectional study | 51 (33F, 18M) | 14.8 ± 2.2 | 1.6 | Parents: 47 | - | Child self-report, parent report of Peds QOL and Peds QOL multidimensional fatigue scale | Moderate | Self-reported fatigue correlated with sleeping difficulty, cognitive dysfunction, physical dysfunction, emotional dysfunction, and academic dysfunction. Parent reported fatigue correlated with sleep difficulty, cognitive dysfunction, physical dysfunction, emotional dysfunction, and academic difficulty. EDSS severity correlated with sleep difficulty, social dysfunction, and physical dysfunction. EDSS severity from parent-reports correlated with onset of fatigue, social dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, physical dysfunction, and academic difficulties. |

| Amato, et al. [39] | Italy | Cohort study | CAMS: 63 (33F, 30M) Ct: 57 (32F, 25M) | CAMS: 15.3 ± 2.5 Ct: 14.8 ± 3.5 | 3.0 ± 3.2 | Parents of CAMS: 41 (30F, 11M) | - | IQ, Expressive language, receptive language, neuropsychological test battery, parent interviews on child’s performance | High | CAMS Lower IQ (verbal and performance) in CAMS than in Ct. Cognitive impairment identified in 27% of cases where CAMS failed in three cognitive test domains, while 53% failed in two test domains. The most common impairment was in spatial recall. Cognitive impairment prevalence was 33% (age 8–13 years), 30% for other groups (14–18 years). Fatigue prominent in 73% of cases. Self-reported depressive symptoms in 6% of cases. Parents: Interviews revealed CAMS had significant impact on school activities and achievements. Only, 10% of CAMS had a support teacher. 22% S had to repeat school year because of missed days or cognitive dysfunction. Likewise, 34% reported a negative impact on hobbies and sports activities due to CAMS and 39% of CAMS had behavioral changes (anxiety, aggressiveness, isolation). |

| Boyd and MacMillan [33] | Canada | Qualitative study | 12 (7F, 5M) | 8–18 | 0.41–10 | - | - | Interviews of experiences associated with diagnosis and coping with CAMS. | Moderate | The main themes were: Learning the diagnosis: Feelings of being “confused”, “scared”, “sadness”, and “pity” reported upon learning of diagnosis. Feelings of “relief” also reported by some CAMS as they finally had an explanation for symptoms. Knowledge of CAMS acquired via parents, healthcare professionals, printed information, self-experience, self-research via school projects, and internet. The most preferable means to obtain the information was described as to being able to read themselves or being talked by someone. Noticing the difference: Most important differences noted since CAMS diagnosis were: heat intolerance, followed by fatigue (5), headache (5), cognitive disabilities (5), sensory symptoms (4), hand tremor (2), seizures (2), depression (1), none (2). Experiences were reported with respect to not being able to perform fine and gross motor skills as before, having difficulties in carrying out school activities, being more cautious than before, and being treated differently than before. Staying the same: Continuing attending school, meeting friends and taking part in social activities was reported by all the CAMS even after diagnosis. Continuing personal activities of interests such as, reading, listening to music, playing on computer were also reported. Coping with CAMS: Stressors: A range of stressors were reported by CAMS that were related to treatment, symptoms, unpredictability of relapses, being treated differently, missing school, effect on family, restriction on lifestyle and uncertainty of future. Strategies: Maintaining a positive outlook on life, continuing to strive for their goals, and making downward comparisons with others having worse life conditions were some of the strategies CAMS implemented to cope. Remaining busy for distracting themselves from their condition, receiving support from others for dealing with CAMS. Negative influences as a mean to cope also were reported by some CAMS. Gaining support: Parents were defined by all CAMS as their main source of support. Moreover, the helpful role of friends and healthcare professionals was also mentioned as they encouraged them to accept their condition and provide information, respectively. Dealing with treatment: Discomfort associated with injection, side effects and cosmetic changes were defined as major aspects contributing towards stress. The injections were also defined as a source of regular reminder of their diagnosis. Some CAMS hid from their peer and family fearing a negative and judgmental outcome on their behalf. Changing relationships: Positive outcomes in relationship were reported between the family post-diagnosis. Teachers were reported maximally to misunderstand the needs of CAMS. Peer response: Most CAMS reported receiving a supportive response from their peers after disclosing the diagnosis. A few reported being downplayed by peers for their symptoms. Exclusions from activities from peers was also documented. Disclosing diagnosis: All the CAMS felt the need to disclose information to close family members, teachers, employers, and friends. Adolescents primarily felt others knowing the diagnosis as a matter of embarrassment and preferred to limit disclosure. Effect learning: Relapses and medical appointments were reported as a major factor for missing school. Moreover, cognitive deficits were reported to affect memory and concentration. Fatigue was also reported to be a main issue that affected their ability to finish a task. Looking towards future: All CAMS described having a feeling of “hope” about the future. None of the CAMS reported that they changed their career goals considering CAMS diagnosis. |

| Experience of CAMS | Studies | CERQual Confidence | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative impact on | School performance | [18,23,25,27,29,33,37,38,39,40,43,44,45,47,48,50] | High | High relevance; minor coherence, data and methodology |

| Social functioning | [18,23,25,29,33,34,35,37,38,43,44,45,48,50] | High | High relevance; minor coherence, data and methodology | |

| Mental health | [18,23,29,33,35,36,37,39,40,41,43,44,47,49] | High | High relevance; minor coherence, data and methodology | |

| Overall physical functioning | [25,26,29,34,37,39,40,42,43,47,50] | High | High relevance; minor coherence, data and methodology | |

| Quality of life | [25,36,43,45,47,48,50] | High | High relevance; minor coherence, data and methodology | |

| Later employment outcomes | [37,44,46] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Barriers | Fatigue | [18,23,25,27,33,35,37,38,39,41,44,48,49] | High | High relevance; minor concerns about coherence, data and methodology |

| Lack of teacher knowledge | [18,29,33,39] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Treatment adherence | [33,36,38] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Adverse effects of treatments | [33,42,50] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Facilitators | Social support | [23,29,33,37,38,45,50] | High | High relevance; minor concerns about coherence, data and methodology |

| Access to disease-modifying therapies | [23,36,43,45,50] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Provisioning of information and developing healthy habits | [28,29,37,38] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology and data, minor coherence | |

| Motivation | [38,45] | Low | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data |

| Experience of Caregivers of Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis | Studies | CERQual Confidence | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative impact on | Social functioning | [18,23,25,26,28,29,34] | High | High relevance; minor concerns about coherence, data and methodology |

| Mental health | [23,26,29,34,42] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Quality of life | [25,26,43] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Employment | [26] | Very Low | High relevance, moderate methodology and data, minor coherence | |

| Diagnosis | Emotional distress | [18,23,25,27,29,33,35,37] | High | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data |

| Healthcare professional’s presence helpful | [23,33] | Low | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Relief after receiving diagnosis | [29,35] | Low | High relevance, moderate methodology and data, minor coherence | |

| Future concerns | Unpredictable outcome of the disease | [18,23,28,29] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data |

| Fear of unable to care the CAMS in future | [23,26] | Low | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Rising treatment costs | [26,41] | Low | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Barriers | Lack of information regarding the disease | [18,23,28] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data |

| Lack of knowledgeable healthcare professional | [27,29,35] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Facilitators | Provision of information on disease management | [18,23,25,29,34,35] | High | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data |

| Including CAMS in the decision-making process | [23,29,35] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Optimistic thinking | [28,33] | Low | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data | |

| Intra-MS family communications | [23,29] | Low | High relevance, moderate methodology and data, minor coherence |

| Needs of Caregivers of CAMS | Studies | CERQual Confidence | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological support | [18,23,25,26,27,28,34,35,37] | High | High relevance; minor concerns about coherence, data and methodology |

| Social support | [18,23,26,28,34,35,37,43] | High | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data |

| Additional information on disease | [18,23,26,27,28,34,35] | High | High relevance; minor concerns about coherence, data and methodology |

| Educational support | [18,23,34] | Moderate | High relevance, moderate methodology, minor coherence and data |

| Financial support | [23] | Very low | High relevance, moderate methodology and data, minor coherence |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghai, S.; Kasilingam, E.; Lanzillo, R.; Malenica, M.; van Pesch, V.; Burke, N.C.; Carotenuto, A.; Maguire, R. Needs and Experiences of Children and Adolescents with Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Review. Children 2021, 8, 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060445

Ghai S, Kasilingam E, Lanzillo R, Malenica M, van Pesch V, Burke NC, Carotenuto A, Maguire R. Needs and Experiences of Children and Adolescents with Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Review. Children. 2021; 8(6):445. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060445

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhai, Shashank, Elisabeth Kasilingam, Roberta Lanzillo, Masa Malenica, Vincent van Pesch, Niamh Caitlin Burke, Antonio Carotenuto, and Rebecca Maguire. 2021. "Needs and Experiences of Children and Adolescents with Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Review" Children 8, no. 6: 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060445

APA StyleGhai, S., Kasilingam, E., Lanzillo, R., Malenica, M., van Pesch, V., Burke, N. C., Carotenuto, A., & Maguire, R. (2021). Needs and Experiences of Children and Adolescents with Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Review. Children, 8(6), 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060445