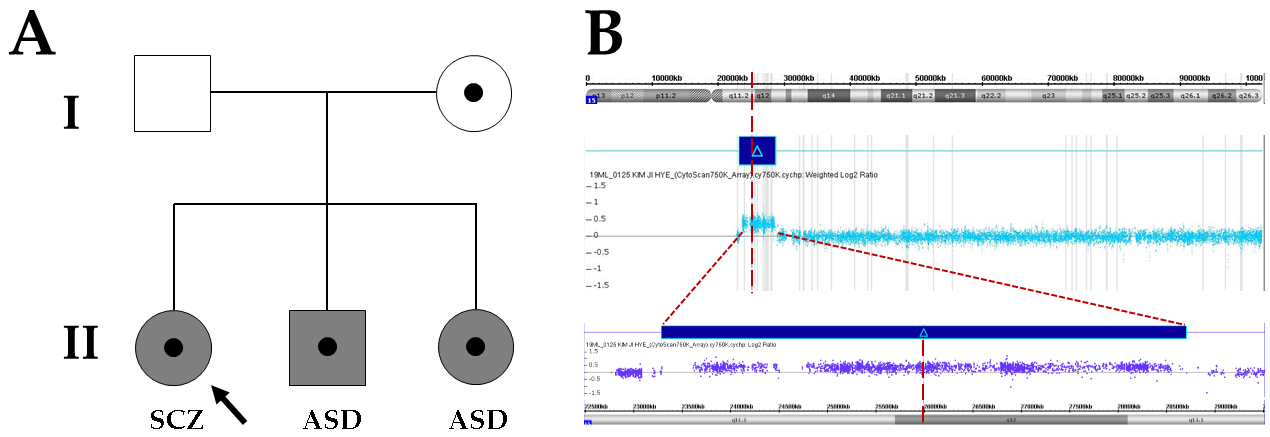

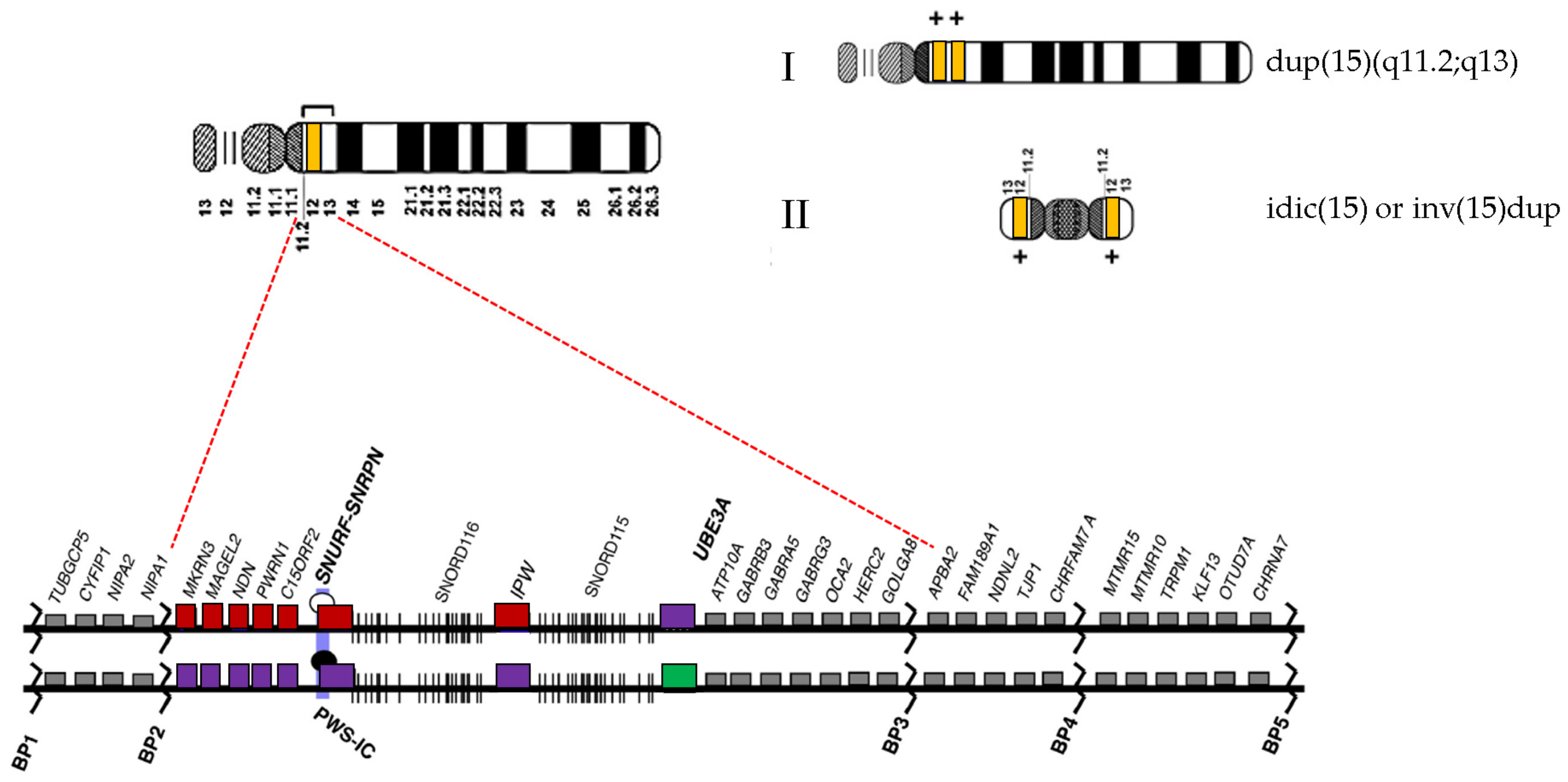

Complete Penetrance but Different Phenotypes in a Korean Family with Maternal Interstitial Duplication at 15q11.2-q13.1: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al Ageeli, E.; Drunat, S.; Delanoë, C.; Perrin, L.; Baumann, C.; Capri, Y.; Fabre-Teste, J.; Aboura, A.; Dupont, C.; Auvin, S.; et al. Duplication of the 15q11-q13 region: Clinical and genetic study of 30 new cases. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2014, 57, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirov, G.; Rees, E.; Walters, J.T.; Escott-Price, V.; Georgieva, L.; Richards, A.L.; Chambert, K.D.; Davies, G.; Legge, S.E.; Moran, J.L.; et al. The Penetrance of Copy Number Variations for Schizophrenia and Developmental Delay. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-De-Luca, D.; Sanders, S.J.; Willsey, A.J.; Mulle, J.G.; Lowe, J.K.; Geschwind, D.H.; State, M.W.; Martin, C.L.; Ledbetter, D.H. Using large clinical data sets to infer pathogenicity for rare copy number variants in autism cohorts. Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogart, A.; Wu, D.; LaSalle, J.M.; Schanen, N.C. The comorbidity of autism with the genomic disorders of chromosome 15q11.2-q13. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 38, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, A. The inv dup (15) or idic (15) syndrome (Tetrasomy 15q). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2008, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.H. Genetics of Autism. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2001, 10, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, B.M.; Lusk, L.; Arkilo, D.; Chamberlain, S.; Devinsky, O.; Dindot, S.; Jeste, S.S.; LaSalle, J.M.; Reiter, L.T.; Schanen, N.C.; et al. 15q Duplication Syndrome and Related Disorders. In GeneReviews(®); Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Mirzaa, G., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington, Seattle Copyright © 1993–2021: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Urraca, N.; Cleary, J.; Brewer, V.; Pivnick, E.K.; McVicar, K.; Thibert, R.L.; Schanen, N.C.; Esmer, C.; Lamport, D.; Reiter, L.T. The Interstitial Duplication 15q11.2-q13 Syndrome Includes Autism, Mild Facial Anomalies and a Characteristic EEG Signature. Autism Res. 2013, 6, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conant, K.D.; Finucane, B.; Cleary, N.; Martin, A.; Muss, C.; Delany, M.; Murphy, E.K.; Rabe, O.; Luchsinger, K.; Spence, S.J. A survey of seizures and current treatments in 15q duplication syndrome. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, D.; Martel, C.; Wilson, A.; Déchambre, N.; Amy, C.; Duverger, L.; Guilé, J.M.; Pipiras, E.; Benzacken, B.; Cave, H.; et al. Brief Report: Visual-Spatial Deficit in a 16-year-old Girl with Maternally Derived Duplication of Proximal 15q. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007, 37, 1585–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, E.W.; Haas-Givler, B.; Finucane, B. A longitudinal follow-up study of autistic symptoms in children and adults with duplications of 15q11-13. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010, 153B, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Gochman, P.; Broadnax, D.D.; Rapoport, J.L.; Ahn, K. 15q13.3 duplication in two patients with childhood-onset schizophrenia. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2016, 171, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, A.S. Parental Origin, DNA Structure, and the Schizophrenia Spectrum. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsiou-Tzeli, S.; Tzetis, M.; Sofocleous, C.; Vrettous, C.; Xaidara, A.; Giannikou, K.; Pampanos, A.; Mavrou, A.; Kanavakis, E. De novo intersititial duplication of the 15q11.2-q14 PWS/AS region of maternal origin: Clinical description, array CGH analysis, and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2010, 152A, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distefano, C.; Gulsrud, A.; Huberty, S.; Kasari, C.; Cook, E.; Reiter, L.T.; Thibert, R.; Jeste, S.S. Identification of a distinct developmental and behavioral profile in children with Dup15q syndrome. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2016, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.H.; Lindgren, V.; Leventhal, B.L.; Courchesne, R.; Lincoln, A.; Shulman, C.; Lord, C.; Courchesne, E. Autism or atypical autism in maternally but not paternally derived proximal 15q duplication. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997, 60, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sinnema, M.; Schrander-Stumpel, C.T.; Maaskant, M.A.; Boer, H.; Curfs, L.M. Aging in Prader-Willi syndrome: Twelve persons over the age of 50 years. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2012, 158A, 1326–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.G.; Kimonis, V.; Dykens, E.; Gold, J.A.; Miller, J.; Tamura, R.; Driscoll, D.J. Prader–Willi syndrome and early-onset morbid obesity NIH rare disease consortium: A review of natural history study. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2018, 176, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsner, L.; Chamberlain, S.J. Prader-Willi, Angelman, and 15q11-q13 Duplication Syndromes. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2015, 62, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piard, J.; Philippe, C.; Marvier, M.; Beneteau, C.; Roth, V.; Valduga, M.; Béri, M.; Bonnet, C.; Gregoire, M.J.; Jonveaux, P.; et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of a large family with an interstitial 15q11q13 duplication. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2010, 152A, 1933–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depienne, C.; Moreno-De-Luca, D.; Heron, D.; Bouteiller, D.; Gennetier, A.; Delorme, R.; Chaste, P.; Siffroi, J.-P.; Chantot-Bastaraud, S.; Benyahia, B. Screening for Genomic Rearrangements and Methylation Abnormalities of the 15q11-q13 Region in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingason, A.; Kirov, G.; Giegling, I.; Hansen, T.; Isles, A.R.; Jakobsen, K.D.; Kristinsson, K.T.; Le Roux, L.; Gustafsson, O.; Craddock, N.; et al. Maternally Derived Microduplications at 15q11-q13: Implication of Imprinted Genes in Psychotic Illness. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Roak, B.J.; Vives, L.; Fu, W.; Egertson, J.D.; Stanaway, I.B.; Phelps, I.G.; Carvill, G.; Kumar, A.; Lee, C.; Ankenman, K.; et al. Multiplex Targeted Sequencing Identifies Recurrently Mutated Genes in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Science 2012, 338, 1619–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guipponi, M.; Santoni, F.A.; Setola, V.; Gehrig, C.; Rotharmel, M.; Cuenca, M.; Guillin, O.; Dikeos, D.; Georgantopoulos, G.; Papadimitriou, G.; et al. Exome Sequencing in 53 Sporadic Cases of Schizophrenia Identifies 18 Putative Candidate Genes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grafodatskaya, D.; Chung, B.; Szatmari, P.; Weksberg, R. Autism Spectrum Disorders and Epigenetics. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 794–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askree, S.H.; Dharamrup, S.; Hjelm, L.N.; Coffee, B. Parent-of-Origin Testing for 15q11-q13 Gains by Quantitative DNA Methylation Analysis. J. Mol. Diagn. 2012, 14, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Features | PWS | AS | Dup15q | II-1 | II-2 | III-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 1/15,000–30,000 | 1/12,000–20,000 | Unknown | |||

| Hypotonia | +++ | + | ++ | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Developmental delay | ++ | +++ | ++ | Absent | Present | Present |

| Intellectual disability | + | +++ | ++ | Present | Present | Present |

| Autism spectrum disorders | + | - | + | Absent | Present | Present |

| Behavioral problems | ++ | + | ++ | Present | Present | Present |

| Tremor and/or ataxia | - | +++ | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Sleep disturbance | ++ | + | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Seizures | - | ++ | + | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Microcephaly | - | ++ | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Strabismus | - | + | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Failure to thrive | +++ | - | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Feeding difficulty | +++ | - | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Hypogonadism | +++ | - | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Hyperphagia | +++ | - | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Obesity | +++ | - | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Short stature/reduced growth | ++ | - | + | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Characteristic facial features | ++ | - | + | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Small hand/feet | ++ | - | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Happy demeanor | - | +++ | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Hyperpigmentation | - | - | + | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Hypopigmentation | ++ | - | - | Absent | Absent | Absent |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, J.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, Y.-M.; Park, J. Complete Penetrance but Different Phenotypes in a Korean Family with Maternal Interstitial Duplication at 15q11.2-q13.1: A Case Report. Children 2021, 8, 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8040313

Han JY, Lee HJ, Lee Y-M, Park J. Complete Penetrance but Different Phenotypes in a Korean Family with Maternal Interstitial Duplication at 15q11.2-q13.1: A Case Report. Children. 2021; 8(4):313. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8040313

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Ji Yoon, Hyun Joo Lee, Young-Mock Lee, and Joonhong Park. 2021. "Complete Penetrance but Different Phenotypes in a Korean Family with Maternal Interstitial Duplication at 15q11.2-q13.1: A Case Report" Children 8, no. 4: 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8040313

APA StyleHan, J. Y., Lee, H. J., Lee, Y.-M., & Park, J. (2021). Complete Penetrance but Different Phenotypes in a Korean Family with Maternal Interstitial Duplication at 15q11.2-q13.1: A Case Report. Children, 8(4), 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8040313