Important Aspects Influencing Delivery of Serious News in Pediatric Oncology: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Aim

2.2. Design

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Information Sources

2.5. Search

- Preliminary search in the MEDLINE database to identify relevant keywords using MeSH terms. The initial search terms were:

- “child”

- “tumor” OR “tumour”

- “communication”

- Keywords and terms identified through this preliminary search were used for the extensive search of the literature. For the MEDLINE database, the following formula was used: (child* OR pediatric* OR paediatric*) AND (oncolog* OR tumor OR tumour* OR cancer OR neoplasm*) AND communicat*.

- Reference lists and bibliographies of the manuscripts retrieved from stages (1) and (2) were searched.

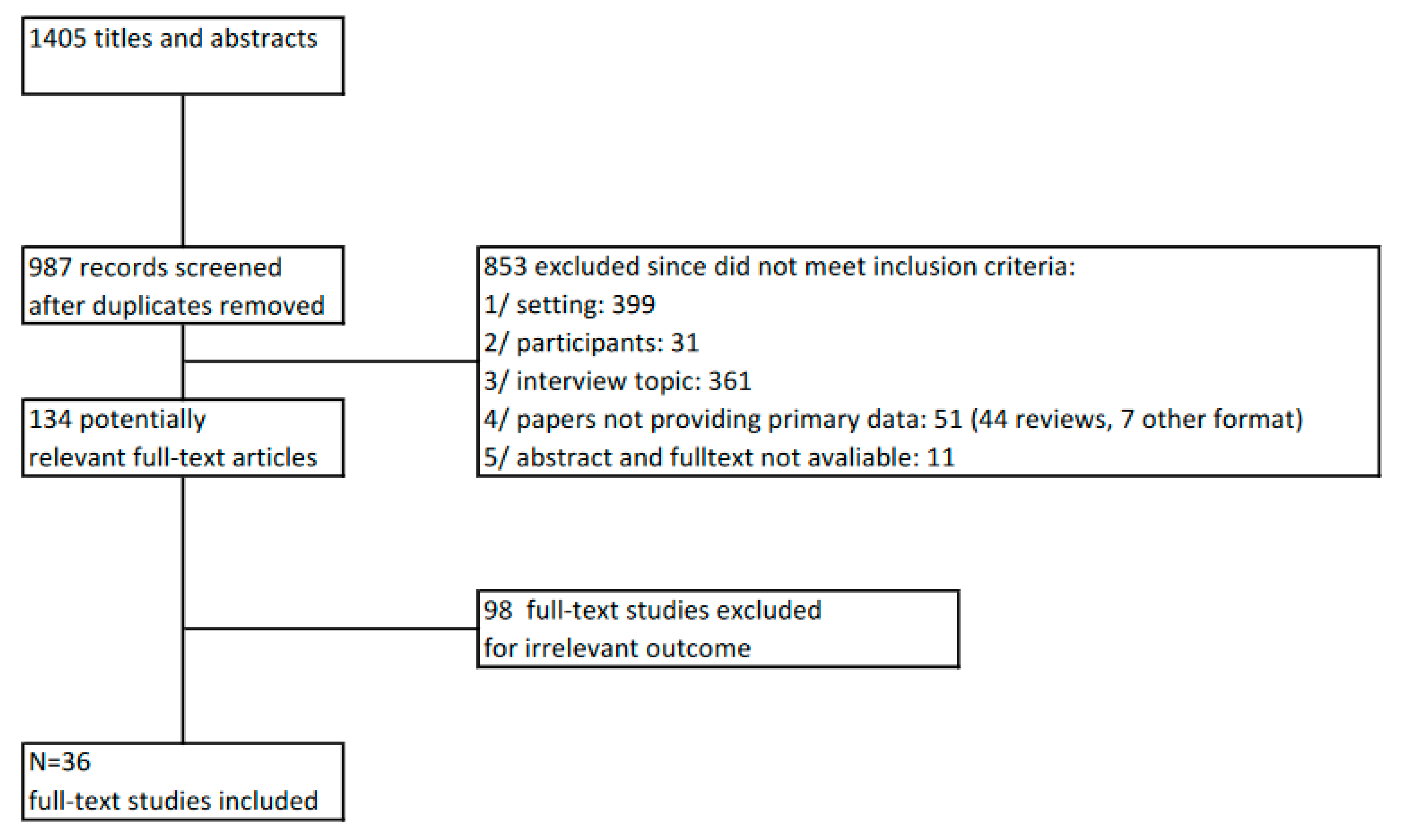

2.6. Study Selection

2.7. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Thematic Groups

3.3. Initial Setting

3.4. Physician’s Approach

3.5. Information Exchange

3.6. Parental Role

3.7. Patient’s Age

3.8. Illness-Related Aspects

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Strength and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaye, E.C.; Friebert, S. Early Integration of Palliative Care for Children with High-Risk Cancer and Their Families. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, E.D.; Levine, J.M. The Day Two Talk: Early Integration of Palliative Care Principles in Pediatric Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4068–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.; Dalton, L. Communication with children and adolescents about the diagnosis of their own life-threatening condition. Lancet 2019, 393, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaman, J.; McCarthy, S. Pediatric palliative care in oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Wolfe, J. Communication About Prognosis Between Parents and Physicians of Children with Cancer: Parent Preferences and the Impact of Prognostic Information. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5265–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Last, B.F.; van Veldhuizen, A.M.H. Information About Diagnosis and Prognosis Related to Anxiety and Depression in Children with Cancer Aged 8–16 Years. Eur. J. Cancer 1996, 32, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaman, J.M.; Torres, C. Parental Perspectives of Communication at the End of Life at a Pediatric Oncology Institution. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.; Gallagher, P. Participation in communication and decision-making: Children and young people’s experiences in a hospital setting. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 2334–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwaanswijk, M.; Tates, K. Communicating with child patients in pediatric oncology consultations: A vignette study on child patients’, parents’, and survivors’ communication preferences. Psycho Oncol. 2011, 20, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amery, J. Practical Handbook of Children’s Palliative Care for Doctors and Nurses Anywhere in the World, 1st ed.; Lulu Publishing Services: Morrisville, NC, USA, 2016; pp. 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, J.W.; Hilden, J.M. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 9155–9161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannen, P.; Wolfe, J. Absorbing information about a child’s incurable cancer. Oncology 2010, 78, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, B.A.; Bluebond-Langner, M. Prognostic disclosures to children: A historical perspective. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranmal, R.; Prictor, M.; Scott, J.T. Interventions for improving communication with children and adolescents about their cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 4, CD002969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Smith, T.J. Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2715–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M.E.; Walling, A. What do we know about giving bad news? A review. Clin. Pediatr. 2010, 49, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baile, W.F.; Buckman, R. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: Application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000, 5, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziewicz, R.; Baile, W.F. Communication skills: Breaking bad news in the clinical setting. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2001, 28, 951–953. [Google Scholar]

- Baile, W.F.; Parker, P.A. Breaking bad news. In Handbook of Communication in Oncology and Palliative Care; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Back, A.L.; Arnold, R.M. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.; Sehring, S.A. Barriers to palliative care for children: Perceptions of pediatric health care providers. Pediatrics 2008, 121, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.; Amory, A. Information-sharing between healthcare professionals, parents and children with cancer: More than a matter of information exchange. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maree, J.E.; Parker, S. The Information Needs of South African Parents of Children with Cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 33, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarau, D.O.; Wangmo, T. Parents’ Challenges and Physicians’ Tasks in Disclosing Cancer to Children. A Qualitative Interview Study and Reflections on Professional Duties in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, 2177–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, A.; Nunes, T. Japanese parents’ perception of disclosing the diagnosis of cancer to their children. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, B.; Hill, J. Is communication guidance mistaken Qualitative study of parent-oncologist communication in childhood cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessel, R.M.; Roth, M. Day One Talk: Parent preferences when learning that their child has cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 2977–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, A.C.; Kaal, J. Bereaved parents and siblings offer advice to health care providers and researchers. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 35, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenmarker, M.; Hallberg, U. Being a Messenger of Life-Threatening Conditions: Experiences of Pediatric. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2010, 55, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwaanswijk, M.; Tates, K. Young patients’, parents’, and survivors’ communication preferences in paediatric oncology: Results of online focus groups. BMC Pediatr. 2007, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdimarsdóttir, U.; Kreicbergs, U. Parents’ intellectual and emotional awareness of their child’s impending death to cancer: A population-based long-term follow-up study. Lancet Oncol. 2007, 8, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, S.K.; Saiki-Craighill, S. Telling children and adolescents about their cancer diagnosis: Cross-cultural comparisons between pediatric oncologists in the US and Japan. Psycho Oncol. 2007, 68, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, R.B.; Marsick, R. Diagnosis, disclosure, and informed consent: Learning from parents of children with cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2000, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, O.B.; Black, I. Communication with parents of children with cancer. Palliat. Med. 1994, 8, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havermans, T.; Eiser, C. Siblings of a child with cancer encouraged or even expected to carry on their lives as if nothing untoward. Child Care Health Dev. 1994, 20, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.; Christie, D. Children with cancer talk about their own death with their families. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 1993, 10, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claflin, C.J.; Barbarin, O.A. Does ‘telling’ less protect more? Relationships among age, information disclosure, and what children with cancer see and feel. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 1991, 16, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essig, S.; Steiner, C. Improving Communication in Adolescent Cancer Care: A Multiperspective Study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 11423–11430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, G.L.; Cardiff, P.M. Parents’ perspectives on the important aspects of care in children dying from life limiting conditions: A qualitative study Introduction: The importance of Paediatric Palliative Care. Med. J. Malays. 2015, 70, 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Lolonga, D.; Pondy, A. L’annonce du diagnostic dans les unités d’oncologie pédiatrique africaines Disclosing a diagnosis in African pediatric oncology units. Rev. Oncol. Hématol. Pédiatr. 2015, 3, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aein, F.; Delaram, M. Giving bad news: A qualitative research exploration. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16, e8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Amano, K. A Comprehensive Study of the Distressing Experiences and Support Needs of Parents of Children with Intractable Cancer. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 44, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Greeff, A.P.; Vansteenwegen, A. Resilience in Families with a Child with Cancer. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 31, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Geest, I.M.M.; Darlington, A.E. Parents’ Experiences of Pediatric Palliative Care and the Impact on Long-Term Parental Grief. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 47, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, F.; Aldiss, S. Children and young people’s experiences of cancer care: A qualitative research study using participatory methods. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1397–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kästel, A.; Enskär, K. Parents’ views on information in childhood cancer care. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersun, L.; Gyi, L. Training in Difficult Conversations: A National Survey of Pediatric Hematology—Oncology and Pediatric Critical Care Physicians. J. Palliat. Med. 2009, 12, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, T.M.; Johnston, D.L. Parental Perceptions of Being Told Their Child Has Cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2008, 51, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, P.M.; Lieberman, S. Troubled parents: Vulnerability and stress in childhood cancer. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1990, 63, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, A.C.; Steward, H. Pediatric Brain Tumor Patients: Their Parents’ Perceptions of the Hospital Experience. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2007, 24, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurková, E.; Andraščíková, I. Parents’ experience with a dying child with cancer in palliative care. Cent. Eur. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2015, 6, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.; Dixon-Woods, M.; Windridge, K.C.; Heney, D. Managing communication with young people who have a potentially life threatening chronic illness: Qualitative study of patients and parents. BMJ 2003, 326, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feraco, A.M.; Brand, S.R. Communication Skills Training in Pediatric Oncology: Moving Beyond Role Modeling. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, A.D.; Frierdich, S.A. Sharing life-altering information: Development of pediatric hospital guidelines and team training. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, A.; Denniston, S. Bad News Deserves Better Communication: A Customizable Curriculum for Teaching Learners to Share Life-Altering Information in Pediatrics. MedEdPORTAL 2016, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazin, L.; Cecchini, C. Communicating Effectively in Pediatric Cancer Care: Translating Evidence into Practice. Children 2018, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, E.A.; Volkan, K. Pediatric residents’ perceptions of communication competencies: Implications for teaching. Med. Teach. 2008, 30, e208–e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.J.; Downar, J. Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: A multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.A.; Stein, T.S. Inaccuracies in physicians’ perceptions of their patients. Med. Care 1999, 37, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group No. | Thematic Group | Aspect | Participant Category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | Physician | Patient | Sibling | ||||

| I | Initial setting | 1 | Privacy | x | |||

| 2 | Patient’s presence | x | X | ||||

| 3 | Family member’s presence | x | |||||

| 4 | Staff member’s presence | x | x | ||||

| 5 | Time and timing | x | x | ||||

| II | Physician’s approach | 6 | Empathy | x | x | X | |

| 7 | Honesty | x | x | X | |||

| 8 | Respect | x | x | X | x | ||

| 9 | “Never-give-up attitude” | x | |||||

| 10 | Close contact | x | x | ||||

| 11 | Responsibility | x | |||||

| III | Information exchange | 12 | Language and vocabulary | x | X | ||

| 13 | Clarity of information | x | X | ||||

| 14 | Amount of information | x | X | x | |||

| 15 | Information content | x | |||||

| 16 | Access to information | x | X | ||||

| 17 | Training | x | |||||

| IV | Parental role | 18 | Child-protective role | x | x | ||

| 19 | Advocacy | x | X | ||||

| 20 | Trust | x | x | ||||

| V | Illness-related factors | 21 | x | x | |||

| VI | Age | 22 | x | x | X | x | |

| Reference | Study Design | Study Objective | Country | Participants | Identified Aspects of Communication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I Coyne, 2016 [25] | Qualitative, audio-recorded individual interviews | To examine participants’ views on children’s participation in decision sharing and communication interactions | Ireland | 20 patients, 22 parents | I–IV, VI |

| JM Snaman, 2016 [7] | Qualitative, tape-recorded discussions in focus groups | To explore communication between staff members and patients and families near the end of life | USA | 22 bereaved parents | II |

| JE Maree, 2016 [26] | Qualitative individual interviews | To explore information needs of parents of children with cancer in South Africa | South Africa | 13 parents | I–III |

| DO Badarau, 2015 [27] | Qualitative, individual semi-structured interviews | Identification of factors that contribute to restricted provision of information about diagnosis to children in Romania | Romania | 18 parents, 10 oncologists | III |

| A Watanabe, 2014 [28] | Qualitative, individual semi-structured tape-recorded interviews | To examine parents’ and grandparents’ views on deciding to share or not to share the diagnosis with the adolescent | Japan | 55 parents, 3 grand-parents | III, V, VI |

| B Young, 2013 [29] | Qualitative, audio-recorded individual semi-structured interviews | Examine perspectives of parents of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia on discussing emotions with oncologists | UK | 67 parents | II |

| RM Kessel, 2013 [30] | Cross-sectional study, mixed design, questionnaire designed by expert panel | Parental preferences when receiving information about child’s diagnosis (setting, length and other parameters of the interview) | USA | 62 parents | I, III, VI |

| AC Steele, 2013 [31] | Cross-sectional qualitative study, individual interviews with open-ended questions tape-recorded | How to improve care for families during the end of life | Canada | 36 mothers, 24 fathers, 39 siblings | II, III |

| M Zwaanswijk, 2011 [9] | Experimental mixed design, questionnaire | Investigate preferences of children with cancer, their parents and survivors regarding medical communication | The Netherlands | 34 patients, 59 parents, 51 survivors | II, VI |

| M Stemarker, 2010 [32] | Qualitative, tape-recorded semi-structured interviews | Main concerns of physicians when informing about malignant disease and psychosocial aspects of being pediatric oncologist | Sweden | 10 oncologists | I–III, VI |

| P Lannen, 2010 [12] | Quantitative, questionnaire | To assess parents‘ ability to absorb information about their child’s cancer being incurable and to identify factors associated with parents’ ability to comprehend this information | Sweden | 191 bereaved mothers, 251 bereaved fathers | I, V |

| M Zwaanswijk, 2007 [33] | Qualitative, online questionnaire for three different focus groups (patients, parents, survivors) | Interpersonal, informational and decisional preferences of parents and patients and survivors | The Netherlands | 7 parents, 11 patients, 18 survivors | I-IV, VI |

| U Valdimarsdóttir, 2007 [34] | Quantitative, questionnaire | Investigation whether care-related factors (i.e., access to information) predicted the timing of parents‘ awareness of child’s impending death | Sweden | 449 bereaved parents | I, V, VI |

| SK Parsons, 2007 [35] | Quantitative, survey questionnaire | Communication practices at diagnosis, difference between disclosure in Japanese and U.S. physicians | USA, Japan | 350 U.S. doctors, 365 doctors from Japan | II, V, VI |

| Mack et al., 2006 [5] | Quantitative, questionnaire | Evaluation of parental preferences for prognostic information about their children with cancer | USA | 194 parents, 20 physicians | II, III, V |

| B Young, 2003 [29] | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews | Management of communication about illness in young people with life-threatening disease and the role of parents in communication process | UK | 19 parents, 13 young people | I–IV |

| RB Levi, 2000 [36] | Qualitative, interviews in focus groups which were designed to include both parents of children enrolled in clinical trial and parents of children not enrolled | To describe retrospective perceptions of parents of the circumstances of their child’s cancer diagnosis and the informed consent process | USA | 22 parents | I–III |

| BF Last et AMH van Veldhuizen, 1996 [6] | Quantitative, questionnaire | To test the hypothesis that being openly informed about the diagnosis and prognosis benefits the emotional well-being of children with cancer | The Netherlands | 56 children, 56 mothers, 54 fathers | III–VI |

| OB Eden, 1994 [37] | Qualitative, structured questionnaire | To assess the receptiveness of parents to information given about their child’s cancer | UK | 23 parents | I, III |

| T Havermans, 1994 [38] | Qualitative, interviews, questionnaire | How children perceive their lives to be affected because of their sibling having cancer | UK | 21 siblings | I, III, V |

| A Goldman, 1993 [39] | Mixed, questionnaire | To discuss whether children dying in hospital had discussed their death with their families and whether any factors in the family appeared to influence dying in hospital setting | UK | 39 died children, questioning the staff members | II |

| CJ Claflin, 1991 [40] | Quantitative, tape-recorded interviews | To address the issue of information disclosure from the child’s perspective | USA | 43 patients | VI |

| S Essig, 2016 [41] | Qualitative, interviews within focus groups | To explore different perspectives on communicating with adolescents with cancer | Switzerland | 12 physicians, 18 nurses, 16 survivors, 8 parents | II, IV |

| Kuan Geok Lan, 2015 [42] | Qualitative, focus group discussions, audio-taped in-depth interviews | To explore parents’ experiences in the end-of-life care of their children and gather their parents‘ views | Malaysia | 15 parents of 9 deceased children (8 diagnosis of cancer, 1 Prader–Willi syndrome) | IV |

| D Lolonga, 2015 [43] | Mixed, semi-structured interviews | To explore the ideal conditions when disclosing diagnosis to parents of children with cancer | African countries | 94 parents, 30 healthcare professionals | I–III |

| F. Aein, 2014 [44] | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews | To explore how mothers in Iran recall receiving information about their child’s diagnosis of cancer | Iran | 14 mothers | I–III, VI |

| S Yoshida, 2014 [45] | Quantitative, multi-center questionnaire survey | To explore the distressing experience of parents of children with intractable cancer | Japan | 135 bereaved parents | II, III |

| AP Greeff, 2014 [46] | Mixed, cross-sectional survey research design, self-report questionnaire | To explore resilience factors associated with family adaptation after child was diagnosed with cancer | Belgium | 26 parents, 25 children | II |

| IMM van der Geest, 2014 [47] | Quantitative, cross-sectional study, questionnaire assessing grief | To explore parents’ perception of the interaction with healthcare professionals and its influence on long-term grief | The Netherlands | 89 bereaved parents | II, III |

| F. Gibson, 2010 [48] | Qualitative, participatory-based techniques of data collection | To explore children’s and young people’s views of cancer care using innovative methods | UK | 16 families | I, VI |

| A Kästel, 2011 [49] | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews | To explore parents’ views on receiving information during childhood cancer care | Sweden | 8 families | I–III |

| L Kersun, 2009 [50] | Quantitative, 12-question web-based survey | To survey recently graduated fellows about their prior training in communication of difficult news | USA | 171 fellows | III |

| TM Parker, 2008 [51] | Quantitative, questionnaire | To assess how parents recall the initial discussion regarding the diagnosis of cancer | Canada | 116 parents | I, VI |

| PM Hughes, 1990 [52] | Qualitative, questionnaire + semi-structured interviews | To assess psychological distresses of parents having child with cancer | UK | 18 parents | V, VI |

| AC Jackson, 2007 [53] | Qualitative, prospective study using a within-group design with repeated measures over time (face-to-face interviews) | To explore coping, adaptation and adjustment in families of a child with brain tumor | Australia | 53 parents | II, III |

| E Gurková, 2014 [54] | Qualitative, semi-structured in-depth interviews | To analyze the parent’s experience when the treatment of their child diagnosed with cancer had failed and the child had died | Slovakia | Bereaved parents: 1 couple, 3 mothers | II, III |

| 1 | Know the diagnosis and the relevant data. | The more serious the news is, the more difficult the discussion may be. Aspects regarding the illness and prognosis play an important role in the delivery of serious news. |

| 2 | Do not overwhelm families with information. | Prepare the key message you need to deliver, keep it short. Some families might ask for more information right away, others will require more information later. |

| 3 | Prepare written information (booklets, leaflets, etc.). | Families find very it helpful to receive information in written form to be able to come back to it later. |

| 4 | Treat your patients and their families with respect. | Being treated respectfully is one of the crucial preferences of children with cancer and their families. |

| 5 | Be authentic. Do not pretend and do not be afraid of truth. | Patients and families do appreciate your openness and honesty. |

| 6 | Be aware of parental protectiveness. | Parents may protect their children from serious news, which presents a potential conflict of interest for the physician as many children and adolescents seek for information about their diagnosis and prognosis. |

| 7 | Mind the patient’s age and mental development. | These important aspects determine not only the patient’s ability to understand the information, but also the parents’ level of protectiveness. |

| 8 | Acknowledge parents’ tendency to hope for the best. | Parents have a unique ability to maintain hope, even if the information given seems hopeless. Parents maintain hope and often want to believe in miracles, no matter what information they received. |

| 9 | Be aware of cultural context. | Cultural aspects play an important role in patients’ and parental perspectives. |

| 10 | Get used to individualized approach. | Do not assume. What works for one family may not work for another. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hrdlickova, L.; Polakova, K.; Loucka, M. Important Aspects Influencing Delivery of Serious News in Pediatric Oncology: A Scoping Review. Children 2021, 8, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8020166

Hrdlickova L, Polakova K, Loucka M. Important Aspects Influencing Delivery of Serious News in Pediatric Oncology: A Scoping Review. Children. 2021; 8(2):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8020166

Chicago/Turabian StyleHrdlickova, Lucie, Kristyna Polakova, and Martin Loucka. 2021. "Important Aspects Influencing Delivery of Serious News in Pediatric Oncology: A Scoping Review" Children 8, no. 2: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8020166

APA StyleHrdlickova, L., Polakova, K., & Loucka, M. (2021). Important Aspects Influencing Delivery of Serious News in Pediatric Oncology: A Scoping Review. Children, 8(2), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8020166