Exposure and Predictive Factors of Postural Development from the Perspective of the Reliability of Their Measurement Tools: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Therefore, the first objective of this work is to define which confounding factors should be taken into account during postural evaluation in children up to 12 years of age so as not to distort or bias the results. The second objective is to identify which methods or tools have been used to analyze postural alignment and to determine which have previously demonstrated reliability and validity, in order to underscore the truthfulness of the reported results—an innovative approach in the present systematic review.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources and Search Methods

- (postural alignment OR postural analysis OR postural evaluation OR postural assessment AND children)

- (posture AND children).

2.2. Study Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- No restriction by publication date in order to identify all possible analyzed factors.

- Language: English, Portuguese, or Spanish. Within search engines, the language with the highest percentage of results is English.

- Study type: descriptive or analytical observational studies.

- Full-text studies.

- Study characteristics by topic: studies that analyzed the subject’s postural pattern in the bipedal or sitting position, and those referring to postural assessment scales or tools under validation or already validated.

- Regarding sample characteristics: studies that assessed only the child population under 12 years of age.

- Without restriction by methodological quality of the studies. In order to avoid excluding studies of low methodological quality that may have used a different tool than those employed in studies with higher quality, and to prevent selection bias for our second objective, this restriction was not applied.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Study type: systematic and literature reviews; case studies or case series with a sample size ≤ 10 children per group; or clinical trials.

- Sample characteristics: children with defined pathology or symptomatology (with the exception of musculoskeletal conditions such as scoliosis).

- Articles not available in open full text.

- Study topic: observational studies that assessed postural control/balance, motor development, etc., in relation to the postural pattern when the latter was the independent variable. Also excluded were studies that assessed a single body region (e.g., neck, head, feet), except for those that assessed the trunk, given its extent and the number of joints involved, as the objective was to understand global postural attitude.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis Methodology

2.4. Assessment of Methodological Quality

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Extracted Variables

- General study characteristics

- Author and year of publication

- Study design

- Sample size

- Population characteristics

- Age or age range within the pediatric population

- Sex

- Subdivisions based on specific parameters according to the type of study (anthropometric variables, presence or absence of postural alterations, age, sex, etc.)

- Posture-related variables

- Postural parameters assessed

- Assessment position (standing or sitting)

- Measurement instruments

- Type of instrument used

- Reported validity and reliability

- Predictive and confounding factors under study (objective)

- Age and sex

- Anthropometry (weight, height, BMI) and body composition–related variables

- Physical activity

- Ergonomic factors

- Environmental factors

- Other factors

- Main outcomes

- Relationship between postural variables and the factors studied

- Secondary associations identified

3. Results

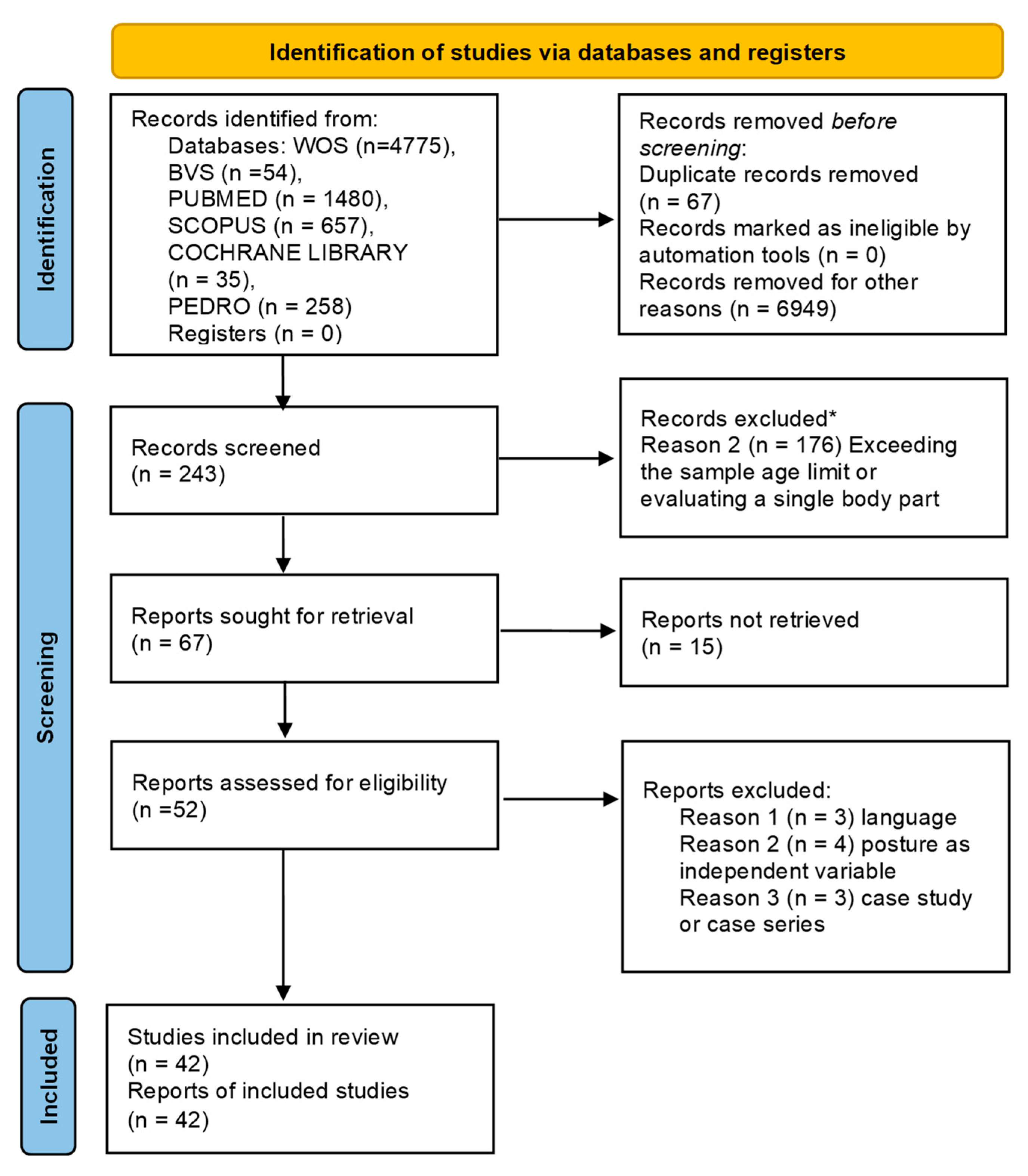

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. General Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Sample Characteristics of Different Studies

- -

- Age

- -

- Sex

- -

- Anthropometric characteristics

- -

- Environmental factors

- -

- Physical and sports activity

- -

- Ergonomic parameters

- -

- Other types of groupings or characteristics selected for the sample population

3.4. Tools Used in the Evaluations of the Included Studies

3.5. Results on the Methodological Quality of the Included Studies

3.6. Results on the Risk of Bias of the Included Studies

3.7. Results of Individual Studies in Relation to the Tools Used

3.8. Results of Individual Studies in Relation to Confounding Factors

- -

- Age as an intra-subject factor

- -

- Sex as an intra-subject factor

- -

- Anthropometry or body composition–related variables, as an intra-subject factor

- -

- Relationship between body structures

- -

- Ergonomic variables as an extra-subject factor

- -

- Physical and sports activity as a factor

4. Discussion

4.1. Reliability of the Tools

4.2. Evidence of Results Considering the Quality of the Tools

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Clinical Implications of the Results Obtained

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EBP | Evidence-based clinical practice |

| SOSORT | Society on Scoliosis Orthopaedic and Rehabilitación Treatment |

| PRISMA | Preferred reporting items for Systematics Reviews and meta-analyses |

| BVS | Virtual Health Library |

| WOS | Web of science |

| NOS | The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| ROBINS | Risk Of Bias In Non-Randomized Studies |

| ROM | Range Of Motion |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| IOTF | International Obesity Task Force |

| AIMS | Alberta Infant Motor Scale |

| máx | maximum |

| mín | minimum |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| ATR | Angle of trunk rotation |

References

- Peterson Kendall, F.; Kendall McCreary, E.; Geise Provance, P.; McIntyre Rodgers, M.; Anthony Romani, W. Músculos: Pruebas, Funciones y Dolor Postural, 4th ed.; Editorial Marbán: Madrid, Spain, 2005; pp. 3, 4, 71, 72, 78, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Barfi, M.; Deligiannis, T.; Schlattmann, B.; Newell, K.M.; Mangalam, M. Wobble Board Instability Enhances Compensatory CoP Responses to CoM Movement Across Timescales. Sensors 2025, 25, 4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vojta, V.; Schweizer, E. El Descubrimiento de la Motricidad Ideal, 1st ed.; Ediciones Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kapandji, A.I. Fisiología Articular: Tronco y Raquis, 5th ed.; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 1999; Volume 3, 10p. [Google Scholar]

- Schmit, E.F.D.; Rui, V.; Pivotto, L.R.; Valle, M.B.D.; Rosa, B.N.D.; Candotti, C.T. Reference values for characterizing the posture of schoolchildren using photogrammetry. Fisioter. Em Mov. 2025, 38, e38124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penha, P.J.; João, S.M.A.; Casarotto, R.A.; Amino, C.J.; Penteado, D.C. Postural assessment of girls between 7 and 10 years of age. Clinics 2005, 60, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafond, D.; Descarreaux, M.; Normand, M.C.; Harrison, D.E. Postural development in school children: A cross-sectional study. Chiropr. Osteopat. 2007, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penha, P.J.; Baldini, M.; João, S.M.A. Spinal postural alignment variance according to sex and age in 7- and 8-year-old children. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2009, 32, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, M.P.; Grimmer, K. Reliability of upright posture measurements in primary school children. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2005, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapo-Gurda, A.; Efendić, A.; Mahmutović, I.; Kovač, S.; Kajmović, H.; Kapo, S.; Šimenko, J. Posture Status Differences Between Preschool Boys and Girls. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, A.P.F.; Martinello, M.; Medeiros DLde Coelho, J.J.; Ries, L.G.K. Effect of the inclination of support in cervical and upper limb development. Fisioter. em Mov. 2014, 27, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, S.; Stanković, M.; Jorgić, B.; Milenković, S.; Smailović, S.; Katanić, B.; Jelaska, I.; Pezelj, L. The Association of Sagittal Spinal Posture among Elementary School Pupils with Sex and Grade. Children 2024, 11, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola, C.; Otzen, T. Los Sesgos en Investigación Clínica. Int. J. Morphol. 2015, 33, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarumma, G.; Mazza, F.; Ambrosi, A.; Keeling, E.; Fernando, F.; Sirico, F.; Gnasso, R.; Demeco, A.; Vecchiato, M.; Motti, M.L.; et al. Sagittal Spinal Alignment in Children and Adolescents: Associations with Age, Weight Status, and Sports Participation. Children 2025, 12, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, S.; Ciobanu, D.I.; Fulop, J.; Matei, N.; Cristea, D.I.; Szabo-Alexi, M.; Blaga, F.N.; Ianc, D.; Ilies, A.B. Postural deficiencies prevalence and correlation with foot conditions, body composition, and coordination, in Romanian preadolescents children: Descriptive observational study. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1621792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhai, M.; Zhou, S.; Jin, Y.; Wen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Han, X. Influence of long-term participation in amateur sports on physical posture of teenagers. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsnok, D.; Mutlu, A.; Livanelioğlu, A. Assessment of spinal alignment in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Clin. Biomech. 2022, 100, 105800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downing, A.M.; Hunter, D.G. Validating clinical reasoning: A question of perspective, but whose perspective? Man. Ther. 2003, 8, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, P.; Pappo, E.; Cameron, M.; Demauroy, J.; Rivard, C.; Kotwicki, T.; Zaina, F.; Wynne, J.; Stikeleather, L.; Bettany-Saltikov, J.; et al. SOSORT 2012 consensus paper: Reducing x-ray exposure in pediatric patients with scoliosis. Scoliosis 2014, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla, M.E. Etapas del desarrollo humano. Rev. Investig. En. Psicol. 2000, 3, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, A.E.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.M.D.C.; Pimenta, C.A.D.M.; Nobre, M.R.C. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, T. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Ciapponi, A. Herramientas ROBINS para evaluar el riesgo de sesgo de estudios no aleatorizados. Evid. Actual. En. Práctica Ambulatoria 2022, 25, e007024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, A. Lower-Limb Range of Motion Predicts Sagittal Spinal Misalignments in Children: A Case-Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmyślna, A.; Żurawski, A.; Rosiński, T.; Pogorzelska, J.; Śliwiński, Z.; Śliwiński, G.; Kiebzak, W. The Relationship Between the Shape of the Spine and the Width of Linea Alba in Children Aged 6-9 Years. Case-Control Study. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 839171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, M.M.B.; Sacco, I.C.N.; João, S.M.A. Caracterização postural da jovem praticante de ginástica olímpica. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2007, 11, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacher, R.; Loudovici-Krug, D.; Wuttke, M.; Spittank, H.; Ammermann, M.; Smolenski, U.C. Development of a Symmetry Score for Infantile Postural and Movement Asymmetries: Preliminary Results of a Pilot Study. J. Chiropr. Med. 2018, 17, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolinski, L.; Kozinoga, M.; Czaprowski, D.; Tyrakowski, M.; Cerny, P.; Suzuki, N.; Kotwicki, T. Two-dimensional digital photography for child body posture evaluation: Standardized technique, reliable parameters and normative data for age 7–10 years. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2017, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedrez, J.A.; Candotti, C.T.; Medeiros, F.S.; Marques, M.T.; Rosa, M.I.Z.; Loss, J.F. Can the adapted arcometer be used to assess the vertebral column in children? Braz. J. Phys. Ther. Impr. 2014, 18, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Silva, M.; Sanada, L.; Alves, C. Análise postural fotogramétrica de crianças saudáveis de 7 a 10 anos: Confiabilidade interexaminadores. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2009, 13, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzał-Grabiec, J.; Snela, S.; Podgórska-Bednarz, J.; Rykała, J.; Banaś, A. Examination of the compatibility of the photogrammetric method with the phenomenon of mora projection in the evaluation of scoliosis. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 162108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzęk, A.; Dworrak, T.; Strauss, M.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Sabbah, I.; Dworrak, B.; Leischik, R. The weight of pupils’ schoolbags in early school age and its influence on body posture. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, F.A.; Lucas, R.; Simpkin, A.J.; Heron, J.; Alegrete, N.; Tilling, K.; Howe, L.D.; Barros, H. Associations of anthropometry since birth with sagittal posture at age 7 in a prospective birth cohort: The Generation XXI Study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łabęcka, M. Changes in body posture parameters: A four-year follow-up study. Cent. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. Med. 2023, 44, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzęk, A.; Knapik, A.; Brzęk, B.; Niemiec, P.; Przygodzki, P.; Plinta, R.; Szyluk, K. Evaluation of Posturometric Parameters in Children and Youth Who Practice Karate: Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5432743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labecka, M.K. Sex-related differences in the sagittal plane spinal angles in preschool and school-age children. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2022, 14, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furian, T.C.; Rapp, W.; Eckert, S.; Wild, M.; Betsch, M. Spinal posture and pelvic position in three hundred forty-five elementary school children: A rasterstereographic pilot study. Orthop. Rev. 2013, 5, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurak, I.; Rađenović, O.; Bolčević, F.; Bartolac, A.; Medved, V. The Influence of the Schoolbag on Standing Posture of First-Year Elementary School Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzał-Grabiec, J.; Snela, S. The influence of rural environment on body posture. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2012, 19, 846–850. [Google Scholar]

- Walicka-Cupryś, K.; Skalska-Izdebska, R.; Rachwał, M.; Truszczyńska, A. Influence of the Weight of a School Backpack on Spinal Curvature in the Sagittal Plane of Seven-Year-Old Children. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 817913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowicz-Szymańska, A.; Fałatowicz, M.; Smoła, E.; Błyszczuk, R.; Wódka, K. Relationship between frontal knee position and the degree of thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis among 10-12-year-old children with normal body weight. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczyński, J.; Lipińska-Stańczak, M.; Wilczyński, I. Body Posture Defects and Body Composition in School-Age Children. Children 2020, 7, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkó, S.; Balkó, I.; Valter, L.; Jelínek, M. Influence of Physical Activities on the Posture in 10-11 Year Old Schoolchildren. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2017, 17, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gołębiowska-Sosnowska, J.; Synder, M.; Gołębiowski, P.; Wojciechowska, K.; Niedzielski, J. Prevalence of Lower Limb Defects in Children in Chosen Kindergartens of the Łódź Agglomeration. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2019, 21, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Almeida, P.; Prudente, G.F.G.; Sá FEde Lima, L.A.O.; Jesus-Moraleida, F.R.; Viana-Cardoso, K.V. Postural and Load Distribution Asymmetries in Preschoolers. Motricidade 2016, 11, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziętek, M.; Machniak, M.; Wójtowicz, D.; Chwałczyńska, A. The Incidence of Body Posture Abnormalities in Relation to the Segmental Body Composition in Early School-Aged Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labecka, M.K. Physical Activity and Parameters of Body Posture in the Frontal Plane in Children. Pol. J. Sport Tour. 2021, 28, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgić, B.M.; Đorđević, S.N.; Hadžović, M.M.; Milenković, S.; Stojiljković, N.Đ.; Olanescu, M.; Peris, M.; Suciu, A.; Popa, D.; Plesa, A. The Influence of Body Composition on Sagittal Plane Posture among Elementary School-Aged Children. Children 2023, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santonja-Medina, F.; Collazo-Diéguez, M.; Martínez-Romero, M.T.; Rodríguez-Ferrán, O.; Aparicio-Sarmiento, A.; Cejudo, A.; Andújar, P.; Sainz De Baranda, P. Classification System of the Sagittal Integral Morphotype in Children from the ISQUIOS Programme (Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, F.A.; Severo, M.; Alegrete, N.; Howe, L.D.; Lucas, R. Defining Patterns of Sagittal Standing Posture in Girls and Boys of School Age. Phys. Ther. 2017, 97, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, F.A.; Martins, A.; Alegrete, N.; Howe, L.D.; Lucas, R. A shared biomechanical environment for bone and posture development in children. Spine J. Off. J. North. Am. Spine Soc. 2017, 17, 1426–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walicka-Cupryś, K.; Drzał-Grabiec, J.; Rachwał, M.; Piwoński, P.; Perenc, L.; Przygoda, Ł.; Zajkiewicz, K. Body Posture Asymmetry in Prematurely Born Children at Six Years of Age. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9302520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzeziński, M.; Czubek, Z.; Niedzielska, A.; Jankowski, M.; Kobus, T.; Ossowski, Z. Relationship between lower-extremity defects and body mass among polish children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz de Baranda, P.; Cejudo, A.; Martínez-Romero, M.T.; Aparicio-Sarmiento, A.; Rodríguez-Ferrán, O.; Collazo-Diéguez, M.; Hurtado-Avilés, J.; Andújar, P.; Santonja-Medina, F. Sitting Posture, Sagittal Spinal Curvatures and Back Pain in 8 to 12-Year-Old Children from the Region of Murcia (Spain): ISQUIOS Programme. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moslemi, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Hosseininejad, M.; Mohtasham, S.; Kabir-Mokamelkhah, E. Assessment of Backpacks Parameters and Postural Structure Disturbances Association among Iranian Children. J. Pediatr. Perspect. 2018, 6, 7413–7419. [Google Scholar]

- Penha, P.J.; Casarotto, R.A.; Sacco, I.C.N.; Marques, A.P.; João, S.M.A. Qualitative postural analysis among boys and girls of seven to ten years of age. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2008, 12, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita Ortega, F.; Ruiz Rodríguez, L.; Zaleta Morales, L.; Fernández Sánchez, M.; Fernández García, R.; Linares Manrique, M. [Analysis of the prevalence of scoliosis and associated factors in a population of Mexican schoolchildren using sifting techniques]. Gac. Med. Mex. 2014, 150, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rusnák, R.; Kolarová, M.; Aštaryová, I.; Kutiš, P. Screening and Early Identification of Spinal Deformities and Posture in 311 Children: Results from 16 Districts in Slovakia. Rehabil. Res. Pract. 2019, 2019, 4758386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozkowiak, M.; Stępień-Słodkowska, M. The impact of a school backpack’s weight, which is carried on the back of a 7-year-old students of both sexes, on the features of body posture in the frontal plane. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górniak, K.; Lichota, M.; Saczuk, J.; Wasiluk, A. Posture and physical fitness in five year-old children. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2024, 24, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Vignerová, J.; Lhotská, L.; Bláha, P. Proposed standard definition for child overweight and obesity. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2001, 9, 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quispe, A.M.; Alvarez-Valdivia, M.G.; Loli-Guevara, S.; Quispe, A.M.; Alvarez-Valdivia, M.G.; Loli-Guevara, S. Metodologías Cuantitativas 2: Sesgo de confusión y cómo controlar un confusor. Rev. Cuerpo Méd Hosp. Nac. Almanzor Aguinaga Asenjo. 2020, 13, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares Arancibia, J.E.; Nanjarí-Miranda, R.; Aranda-Bustamante, F.; Saavedra-León, V.; Zuñiga-Vivanco, J.; Castillo-Paredes, A.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R. Higiene postural: Factores que influyen en una correcta postura en niños y adolescentes. Una Revisión Sist. 2024, 56, 374–384. [Google Scholar]

- Tanure, M.C.; Pinheiro, A.P.; Oliveira, A.S. Reliability assessment of Cobb angle measurements using manual and digital methods. Spine J. 2010, 10, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gstoettner, M.; Sekyra, K.; Walochnik, N.; Winter, P.; Wachter, R.; Bach, C.M. Inter- and intraobserver reliability assessment of the Cobb angle: Manual versus digital measurement tools. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liang, J.; Du, Y.; Tan, X.; Xiang, X.; Wang, W.; Ru, N.; Le, J. Reliability and reproducibility analysis of the Cobb angle and assessing sagittal plane by computer-assisted and manual measurement tools. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2014, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRoberts, L.B.; Cloud, R.M.; Black, C.M. Evaluation of the New York Posture Rating Chart for Assessing Changes in Postural Alignment in a Garment Study. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2013, 31, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadinia, F.; Kamyab, M.; Behtash, H.; Saleh Ganjavian, M.; Javaheri, M.R.M. The validity and reliability of noninvasive methods for measuring kyphosis. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2014, 27, E212–E218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.V.; Andrade, R.M.; Novo, N.F.; Ribeiro, A.P. Reliability and validity between two instruments for measuring spine sagittal parameters in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis during various stages of growth. Med. Leg. Costa Rica 2022, 39, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Navali, A.M.; Bahari, L.A.S.; Nazari, B. A comparative assessment of alternatives to the full-leg radiograph for determining knee joint alignment. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rehabil. Ther. Technol. 2012, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, D.M.; Bonagamba, G.H.; Oliveira, A.S. Scoliometer measurements of patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2013, 17, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabard-Fougère, A.; Bonnefoy-Mazure, A.; Hanquinet, S.; Lascombes, P.; Armand, S.; Dayer, R. Validity and Reliability of Spine Rasterstereography in Patients With Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 2017, 42, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walicka-Cupryś, K.; Wyszyńska, J.; Podgórska-Bednarz, J.; Drzał-Grabiec, J. Concurrent validity of photogrammetric and inclinometric techniques based on assessment of anteroposterior spinal curvatures. Eur. Spine J. 2018, 27, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takács, M.; Orlovits, Z.; Jáger, B.; Kiss, R.M. Comparison of spinal curvature parameters as determined by the ZEBRIS spine examination method and the Cobb method in children with scoliosis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, K.R.; Colombo, A.S.; João, S.M.A. Reliability and validity of the photogrammetry for scoliosis evaluation: A cross-sectional prospective study. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2009, 32, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifnezhad, A.; Raissi, G.R.; Forogh, B.; Soleymanzadeh, H.; Mohammadpour, S.; Daliran, M.; Cham, M.B. The Validity and Reliability of Kinovea Software in Measuring Thoracic Kyphosis and Lumbar Lordosis. Iran. Rehabil. J. 2021, 19, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaner, M.F.; Mota, Y.L.; Rocha Viana, A.C.; dos Santos, M.C. Fotogrametria: Fidedignidade e falta de objetividade na avaliação postural. Motricidade 2012, 8, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mirón-Pérez, T.; Sánchez-González, J.L.; Navarro-López, V.; Menendez-Pardiñas, M.; I, S.-E. Exposure and Predictive Factors of Postural Development from the Perspective of the Reliability of Their Measurement Tools: A Systematic Review. Children 2026, 13, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010076

Mirón-Pérez T, Sánchez-González JL, Navarro-López V, Menendez-Pardiñas M, I S-E. Exposure and Predictive Factors of Postural Development from the Perspective of the Reliability of Their Measurement Tools: A Systematic Review. Children. 2026; 13(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirón-Pérez, Tania, Juan Luis Sánchez-González, Víctor Navarro-López, Mónica Menendez-Pardiñas, and Sanz-Esteban I. 2026. "Exposure and Predictive Factors of Postural Development from the Perspective of the Reliability of Their Measurement Tools: A Systematic Review" Children 13, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010076

APA StyleMirón-Pérez, T., Sánchez-González, J. L., Navarro-López, V., Menendez-Pardiñas, M., & I, S.-E. (2026). Exposure and Predictive Factors of Postural Development from the Perspective of the Reliability of Their Measurement Tools: A Systematic Review. Children, 13(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010076