Mother–Preterm Infant Contingent Interactions During Supported Infant-Directed Singing in the NICU—A Feasibility Study

Abstract

Highlights

- We demonstrate feasible behavioral scales to measure contingency between mothers and preterm infants’ behaviors during supported infant-directed singing.

- Preterm infants exhibit regulated behaviors during supported mother-led, infant-directed singing.

- Supported infant-directed singing may facilitate regulation.

- This regulation of infant-directed singing may benefit developmental outcomes of preterm infants.

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Intervention and Procedure

2.3. Development of Behavioral Coding

- Maternal behaviors: affect; head orientation; vocalizations (second-by-second, i.e., 1 rating per s); movements of hands, head, and legs (frame-by-frame, i.e., 1 rating per 1/30 s).

- Infant behaviors: head orientation; eye-opening; hand positioning (second-by-second); movements (frame-by-frame).

- Maternal behaviors: overall affective tone.

- Infant behaviors: body orientation; state of alertness [58].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Description of Observed Behaviors

3.1.1. Macro Behaviors Are Shown in Supplementary Table S1

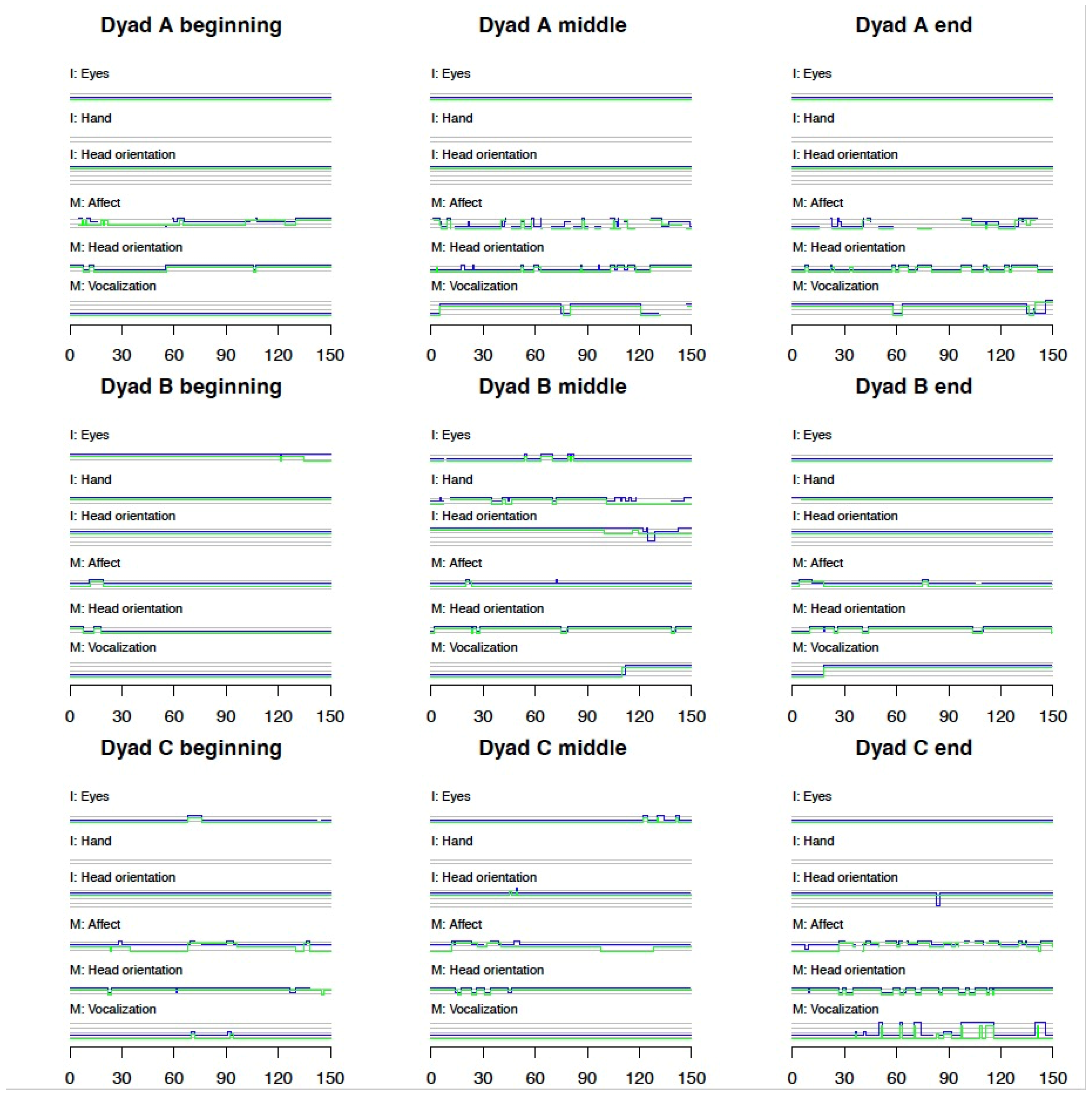

3.1.2. Micro Behaviors Are Shown in Figure 1 (Dyads A–C) and Figure 2 (Dyad D)

3.1.3. Frame-by-Frame Micro Scales

3.2. Inter-Rater Reliability

3.3. Contingent Behaviors During IDS (Table 4)

| Infant | Mother | OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Singing | Singing | |||

| Eyes closed | 745 | 416 | 0 (0 to 0.04) | <0.001 |

| Eyes open | 177 | 0 | ||

| Hands extended | 22 | 13 | 0.91 (0.43 to 2.05) | 0.85 |

| Hands centered | 256 | 139 | ||

| Head not toward mother | 618 | 151 | 3.54 (2.76 to 4.55) | <0.001 |

| Head toward mother | 306 | 265 | ||

| Head not toward infant | Head toward infant | |||

| Eyes closed | 341 | 826 | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.17) | <0.001 |

| Eyes open | 138 | 39 | ||

| Hands extended | 5 | 30 | 0.22 (0.08 to 0.59) | <0.001 |

| Hands centered | 169 | 226 | ||

| Head not toward mother * | 213 | 546 | 0.47 (0.37 to 0.59) | <0.001 |

| Head toward mother | 266 | 320 | ||

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| IDS | Infant Directed Singing |

| MT | Music Therapy |

References

- Aarnoudse-Moens, C.S.H.; Weisglas-Kuperus, N.; Van Goudoever, J.B.; Oosterlaan, J. Meta-Analysis of Neurobehavioral Outcomes in Very Preterm and/or Very Low Birth Weight Children. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavente-Fernández, I.; Synnes, A.; Grunau, R.E.; Chau, V.; Ramraj, C.; Glass, T.; Cayam-Rand, D.; Siddiqi, A.; Miller, S.P. Association of Socioeconomic Status and Brain Injury with Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Very Preterm Children. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e192914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, E.H.; Chou, J.; Brown, K.A. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants: A recent literature review. Transl. Pediatr. 2020, 9, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.A.S.; Hoffenkamp, H.N.; Tooten, A.; Braeken, J.; Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M.; Van Bakel, H.J.A. Child-Rearing History and Emotional Bonding in Parents of Preterm and Full-Term Infants. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-4-154991-2. [Google Scholar]

- Linsell, L.; Malouf, R.; Morris, J.; Kurinczuk, J.J.; Marlow, N. Risk Factor Models for Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Children Born Very Preterm or With Very Low Birth Weight: A Systematic Review of Methodology and Reporting. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 185, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potharst, E.S.; Houtzager, B.A.; Van Sonderen, L.; Tamminga, P.; Kok, J.H.; Last, B.F.; Van Wassenaer, A.G. Prediction of cognitive abilities at the age of 5 years using developmental follow-up assessments at the age of 2 and 3 years in very preterm children. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2012, 54, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, S.A.; Paulsen, M.E. EBNEO commentary: Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms in parents of very preterm infants while hospitalised and post-discharge. Acta Paediatr. 2022, 111, 1648–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allotey, J.; Zamora, J.; Cheong-See, F.; Kalidindi, M.; Arroyo-Manzano, D.; Asztalos, E.; Van Der Post, J.; Mol, B.; Moore, D.; Birtles, D.; et al. Cognitive, motor, behavioural and academic performances of children born preterm: A meta-analysis and systematic review involving 64 061 children. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 125, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R.; Eidelman, A.I. Maternal postpartum behavior and the emergence of infant–mother and infant–father synchrony in preterm and full-term infants: The role of neonatal vagal tone. Dev. Psychobiol. 2007, 49, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harel, H.; Gordon, I.; Geva, R.; Feldman, R. Gaze Behaviors of Preterm and Full-Term Infants in Nonsocial and Social Contexts of Increasing Dynamics: Visual Recognition, Attention Regulation, and Gaze Synchrony. Infancy. 2011, 16, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westrup, B. Family-Centered Developmentally Supportive Care. NeoReviews 2014, 15, e325–e335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, A.; Wolke, D. Maternal Sensitivity in Parenting Preterm Children: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e177–e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givrad, S.; Hartzell, G.; Scala, M. Promoting infant mental health in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU): A review of nurturing factors and interventions for NICU infant-parent relationships. Early Hum. Dev. 2021, 154, 105281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzell, G.; Shaw, R.J.; Givrad, S. Preterm infant mental health in the neonatal intensive care unit: A review of research on NICU parent-infant interactions and maternal sensitivity. Infant Ment. Health J. 2023, 44, 837–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Als, H.; Duffy, F.H.; McAnulty, G.B.; Rivkin, M.J.; Vajapeyam, S.; Mulkern, R.V.; Warfield, S.K.; Huppi, P.S.; Butler, S.C.; Conneman, N.; et al. Early Experience Alters Brain Function and Structure. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korja, R.; Latva, R.; Lehtonen, L. The effects of preterm birth on mother–infant interaction and attachment during the infant’s first two years. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelli, M.; Stefana, A.; Lee, S.H.; Beebe, B. Preterm infant contingent communication in the neonatal intensive care unit with mothers versus fathers. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 58, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthussery, S.; Chutiyami, M.; Tseng, P.-C.; Kilby, L.; Kapadia, J. Effectiveness of early intervention programs for parents of preterm infants: A meta-review of systematic reviews. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittle, A.; Orton, J.; Anderson, P.J.; Boyd, R.; Doyle, L.W. Early developmental intervention programmes provided post hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairment in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 11, CD005495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippa, M.; Panza, C.; Ferrari, F.; Frassoldati, R.; Kuhn, P.; Balduzzi, S.; D’Amico, R. Systematic review of maternal voice interventions demonstrates increased stability in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslbeck, F.B.; Karen, T.; Loewy, J.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Bassler, D. Musical and vocal interventions to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes for preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, CD013472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloch, S. Mothers and infants and communicative musicality. Music. Sci. 1999, 3 (Suppl. S1), 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloch, S.; Trevarthen, C. Musicality: Communicating the vitality and interests of life. In Communicative Musicality; Malloch, S., Trevarthen, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-0-19-856628-1. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D.N. The Interpersonal World of the Infant: A View from Psychoanalysis and Developmental Psychology, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-429-48213-7. [Google Scholar]

- Trehub, S.E.; Cirelli, L.K. Precursors to the performing arts in infancy and early childhood. In Progress in Brain Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 237, pp. 225–242. ISBN 978-0-12-813981-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tronick, E.Z. Emotions and Emotional Communication in Infants. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewy, J.; Jaschke, A.C. Mechanisms of Timing, Timbre, Repertoire, and Entrainment in Neuroplasticity: Mutual Interplay in Neonatal Development. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieleninik, Ł.; Ghetti, C.; Gold, C. Music Therapy for Preterm Infants and Their Parents: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20160971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzi, A.; Nunes, C.C.; Piccinini, C.A. Music therapy and musical stimulation in the context of prematurity: A narrative literature review from 2010–2015. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e1–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standley, J. Music Therapy Research in the NICU: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Neonatal Netw. 2012, 31, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, W.; Han, X.; Luo, J.; Zeng, Z.; Yang, M. Effect of music therapy on preterm infants in neonatal intensive care unit: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S.; Elefant, C.; Arnon, S.; Ghetti, C. Music therapy spanning from NICU to home: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of Israeli parents’ experiences in the LongSTEP Trial. Nord. J. Music. Ther. 2023, 32, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghetti, C.M.; Gaden, T.S.; Bieleninik, Ł.; Kvestad, I.; Assmus, J.; Stordal, A.S.; Aristizabal Sanchez, L.F.; Arnon, S.; Dulsrud, J.; Elefant, C.; et al. Effect of Music Therapy on Parent-Infant Bonding Among Infants Born Preterm: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2315750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R. Sensitive periods in human social development: New insights from research on oxytocin, synchrony, and high-risk parenting. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Reisner, S.; Lueger, A.; Wass, S.V.; Hoehl, S.; Markova, G. Sing to me, baby: Infants show neural tracking and rhythmic movements to live and dynamic maternal singing. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2023, 64, 101313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Cui, H.; Ma, Y. Hyperscanning Studies on Interbrain Synchrony and Child Development: A Narrative Review. Neuroscience 2023, 530, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djalovski, A.; Dumas, G.; Kinreich, S.; Feldman, R. Human attachments shape interbrain synchrony toward efficient performance of social goals. NeuroImage 2021, 226, 117600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markova, G.; Nguyen, T.; Hoehl, S. Neurobehavioral Interpersonal Synchrony in Early Development: The Role of Interactional Rhythms. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wass, S.V.; Phillips, E.A.M.; Haresign, I.M.; Amadó, M.P.; Goupil, L. Contingency and Synchrony: Interactional Pathways Toward Attentional Control and Intentional Communication. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2024, 6, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, A.E.; Rochat, P. Two-Month-Old Infants’ Sensitivity to Social Contingency in Mother–Infant and Stranger–Infant Interaction. Infancy 2006, 9, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Lohaus, A.; Völker, S.; Cappenberg, M.; Chasiotis, A. Temporal Contingency as an Independent Component of Parenting Behavior. Child Dev. 1999, 70, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abney, D.H.; Warlaumont, A.S.; Oller, D.K.; Wallot, S.; Kello, C.T. Multiple Coordination Patterns in Infant and Adult Vocalizations. Infancy 2017, 22, 514–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohlfing, K.J.; Leonardi, G.; Nomikou, I.; Raczaszek-Leonardi, J.; Hullermeier, E. Multimodal Turn-Taking: Motivations, Methodological Challenges, and Novel Approaches. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2020, 12, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, S.; Devouche, E.; Apter, G.; Gratier, M. The Roots of Turn-Taking in the Neonatal Period. Infant Child. Dev. 2016, 25, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoušek, H.; Papoušek, M. Structure and dynamics of human communication at the beginning of life. Eur. Arch. Psychiatr. Neurol. Sci. 1986, 236, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.E.S.; Justo, J.M.R.M.; Gratier, M.; Tomé, T.; Pereira, E.; Rodrigues, H. Vocal responsiveness of preterm infants to maternal infant-directed speaking and singing during skin-to-skin contact (Kangaroo Care) in the NICU. Infant Behav. Dev. 2019, 57, 101332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.E.; Justo, J.M.; Gratier, M.; Ferreira Rodrigues, H. Infants’ overlapping vocalizations during maternal humming: Contributions to the synchronization of preterm dyads. Psychol. Music. 2021, 49, 1654–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coco, M.I.; Dale, R. Cross-recurrence quantification analysis of categorical and continuous time series: An R package. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefana, A.; Lavelli, M. Parental engagement and early interactions with preterm infants during the stay in the neonatal intensive care unit: Protocol of a mixed-method and longitudinal study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markova, G.; Nguyen, T.; Schätz, C.; De Eccher, M. Singing in Tune—Being in Tune: Relationship Between Maternal Playful Singing and Interpersonal Synchrony. Enfance 2020, 1, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papile, L.-A.; Burstein, J.; Burstein, R.; Koffler, H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: A study of infants with birth weights less than 1500 gm. J. Pediatr. 1978, 92, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaden, T.S.; Ghetti, C.; Kvestad, I.; Gold, C. The LongSTEP approach: Theoretical framework and intervention protocol for using parent-driven infant-directed singing as resource-oriented music therapy. Nord. J. Music. Ther. 2022, 31, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewy, J. Music therapy for hospitalized infants and their parents. In Music Therapy and Parent–Infant Bonding; Edwards, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 179–190. ISBN 978-0-19-958051-4. [Google Scholar]

- Loewy, J. NICU music therapy: Song of kin as critical lullaby in research and practice. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1337, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beebe, B.; Jaffe, J.; Markese, S.; Buck, K.; Chen, H.; Cohen, P.; Bahrick, L.; Andrews, H.; Feldstein, S. The origins of 12-month attachment: A microanalysis of 4-month mother–infant interaction. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2010, 12, 3–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefana, A.; Lavelli, M.; Rossi, G.; Beebe, B. Interactive sequences between fathers and preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 140, 104888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazelton, T.B.; Nugent, J.K. The Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale; Mac Keith Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holle, H.; Rein, R. EasyDIAg: A tool for easy determination of interrater agreement. Behav. Res. Methods 2015, 47, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlovsky, L. Aesthetic emotions, what are their cognitive functions? Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Als, H. Toward a synactive theory of development: Promise for the assessment and support of infant individuality. Infant Ment. Health J. 1982, 3, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Als, H. Reading the premature infant. In Developmental Interventions in the Neonatal Intensive Care Nursery; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 18–85. [Google Scholar]

- Arnon, S.; Diamant, C.; Bauer, S.; Regev, R.; Sirota, G.; Litmanovitz, I. Maternal singing during kangaroo care led to autonomic stability in preterm infants and reduced maternal anxiety. Acta Paediatr. 2014, 103, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakobson, D.; Gold, C.; Beck, B.D.; Elefant, C.; Bauer-Rusek, S.; Arnon, S. Effects of Live Music Therapy on Autonomic Stability in Preterm Infants: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Children 2021, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebuza, G.; Kaźmierczak, M.; Leńska, K. The effects of kangaroo mother care and music listening on physiological parameters, oxygen saturation, crying, awake state and sleep in infants in NICU. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 3659–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Lai, X.; Liao, J.; Tan, Y. Effect of non-pharmacological interventions on sleep in preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit: A protocol for systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e27587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentner, T.; Wang, X.; De Groot, E.R.; Van Schaijk, L.; Tataranno, M.L.; Vijlbrief, D.C.; Benders, M.J.N.L.; Bartels, R.; Dudink, J. The Sleep Well Baby project: An automated real-time sleep–wake state prediction algorithm in preterm infants. Sleep 2022, 45, zsac143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemark, H. Time Together: A Feasible Program to Promote parent-infant Interaction in the NICU. Music. Ther. Perspect. 2018, 36, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainor, L.J. Infant preferences for infant-directed versus noninfant-directed playsongs and lullabies. Infant Behav. Dev. 1996, 19, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Flaten, E.; Trainor, L.J.; Novembre, G. Early social communication through music: State of the art and future perspectives. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2023, 63, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Infant | Mother | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject ID | Sex | GA (Weeks; Days) | PMA at Study Entry (Weeks; Days) | Weight at Birth (Grams) | IVH | PVL | BPD | Duration of Oxygen Support (Days) | ROP | Age (Years) | Education (Years) | Parity |

| A | f | 31; 3 | 35; 3 | 1730 | Grade 1—right | No | No | 11 | None | 41 | 15 | 2 |

| B | m | 31; 4 | 35; 2 | 1748 | No | No | No | 3 | None | 30 | 15 | 2 |

| C | f | 24; 2 | 36; 2 | 640 | Grade 2—Left | No | No | 42 | Stage 1—Left eye | 31 | 15 | 1 |

| D | f | 27; 6 | 38; 3 | 660 | No | No | No | 56 | Stage 2—Left eye | 27 | 12 | 1 |

| Behavior | Time Scale (Seconds) | Values | Description | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant behaviors | ||||

| Body orientation | 150 | 0—away from mother | body is oriented away from mother’s body | macro scale coding is according to the behavior that is observable for most of the video segment the head orientation is determined from the infant’s perspective |

| 1—frontal | body is oriented toward the ceiling | |||

| 2—toward mother | body is oriented toward the mother | |||

| Eye opening | 1 | 0—eyes closed | eyes are closed | eyes can be either squeezed or relaxed. eyes could be very slightly open but the pupil is not seen |

| 1—eyes open | eyes are open | eyes can be either narrow or wide open with detectable pupil | ||

| Hand position | 1 | 0—hands extended | palms extended or stretched facing away from infant | behavior may appear in any of the following manners: one or both hands are extended; fingers of one or two hands are spread (hand either flexed or extended); hands facing away from infant; hands flaccid (lay on the sides of the body); hands flail; airplane position; salute position |

| 1—hands centred | both hands are centered toward the infant | behavior may appear in any of the following manners: placed in front, close or touching the face; tucked close to body center or torso; one to mouth, one centred; clasped; one grasping (object), one centred | ||

| Head orientation | 1 | 0—away from mother | the head orientation is determined from the infant’s perspective | |

| 1—upwards (not used) | head faces up | |||

| 2—downwards (not used) | head faces down | |||

| 3—frontal | head faces the ceiling | |||

| 4—towards mother | ||||

| States of alertness | 150 | 0—fussy | distinct signs of discomfort: eye or mouth squinting, cry | |

| 1—quite alert | eyes are open and focused | |||

| 2—drowsy | eyes open and close rapidly; eyes can be open but without focus | |||

| 3—sleep | deep or light sleep state; eyes are closed with subtle to no bodily movements | movements can be either rapid or slow, as long as the infant is not fussy and eyes are closed | ||

| Movements | 1/30 (only in dyad “y”) | 0—no movement | no distinct or meaningful movement | movements are observable in facial organs (eyes, eyebrows, mouth, lips), head, or hands each movement is coded compared to the previous frame, unless it is a part of continuous movement within a continuous movement, a pause of up to half a second (15 frames) will be considered movement |

| 1—movement | big or distinct movement | |||

| Maternal behaviors | ||||

| Affect | 1 | 0—negative | negative emotions like distress, fretting, anger, sadness, or discontentment with mouth curled or grimacing | |

| 1—neutral | neither smile nor distress signs | |||

| 2—positive | smile with the mouth (open or closed) turned upward (i.e., contraction of cheek muscle), possibly contraction of the under-eye muscle, causing wrinkles in the eye region | |||

| Affective tone | 150 | 0—negative | negative | macro scale determined according to the overall tone of the interaction from the parent side |

| 1—neutral | neutral | |||

| 2—positive | positive | |||

| Head orientation | 1 | 0—away from infant | head faces ceiling, leans backwards, faces another adult | |

| 1—toward infant | ||||

| Vocalizations | 1 | 0—no vocalization | ||

| 1—speech | infant-directed speech, verbalizations, rhymes | |||

| 2—singing | melodic vocalizations, humming | |||

| 3—adult speech | speech with another adults present (another parent, researcher, staff member) | |||

| Head movements | 1/30 (only in dyad D) | 0—no movement | each movement is coded compared to the previous frame, unless it is a part of continuous movement within a continuous movement, a pause of up to half a second (15 frames) will be considered movement | |

| 1—movement | ||||

| Leg movements | 0—no movement 1—movement | |||

| Left hand movements | 0—no movement 1—movement | |||

| Right hand movements | 0—no movement 1—movement | |||

| Variable | N 1 | Cohen’s Kappa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Infant body orientation | 1056 | NA 2 |

| Infant eyes (I1) | 1355 | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.96) |

| Infant hand position (I2) | 426 | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.89) |

| Infant head orientation (I3) | 1358 | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.96) |

| Infant states of alertness | 1358 | 0.71 (0.69 to 0.77) |

| Maternal affect (M1) | 1183 | 0.59 (0.55 to 0.63) |

| Maternal affective tone | 1363 | 0.50 (0.45 to 0.55) |

| Maternal head orientation (M2) | 1349 | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.97) |

| Maternal vocalizations (M3) | 1342 | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.96) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Epstein, S.; Arnon, S.; Markova, G.; Nguyen, T.; Hoehl, S.; Eitan, L.; Bauer-Rusek, S.; Yakobson, D.; Gold, C. Mother–Preterm Infant Contingent Interactions During Supported Infant-Directed Singing in the NICU—A Feasibility Study. Children 2025, 12, 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091273

Epstein S, Arnon S, Markova G, Nguyen T, Hoehl S, Eitan L, Bauer-Rusek S, Yakobson D, Gold C. Mother–Preterm Infant Contingent Interactions During Supported Infant-Directed Singing in the NICU—A Feasibility Study. Children. 2025; 12(9):1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091273

Chicago/Turabian StyleEpstein, Shulamit, Shmuel Arnon, Gabriela Markova, Trinh Nguyen, Stefanie Hoehl, Liat Eitan, Sofia Bauer-Rusek, Dana Yakobson, and Christian Gold. 2025. "Mother–Preterm Infant Contingent Interactions During Supported Infant-Directed Singing in the NICU—A Feasibility Study" Children 12, no. 9: 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091273

APA StyleEpstein, S., Arnon, S., Markova, G., Nguyen, T., Hoehl, S., Eitan, L., Bauer-Rusek, S., Yakobson, D., & Gold, C. (2025). Mother–Preterm Infant Contingent Interactions During Supported Infant-Directed Singing in the NICU—A Feasibility Study. Children, 12(9), 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091273