Temperament Development During the First Year of Life in a Sample of Patients with Hearing Impairment Who Participated in the Infants Screening Program in a Single Center in Southern Italy: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

Highlights

- The development of temperament in the newborn and its interaction with listening skills is a complex process and its evaluation requires a longer observation time for the child than a year of life.

- The QUIT questionnaire proved to be a more effective tool for raising parents’ awareness of children’s behavioral and cognitive problems than for drawing a behavioral profile.

- This study suggests the need for a multidisciplinary approach in the evaluation of newborns with hearing loss.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

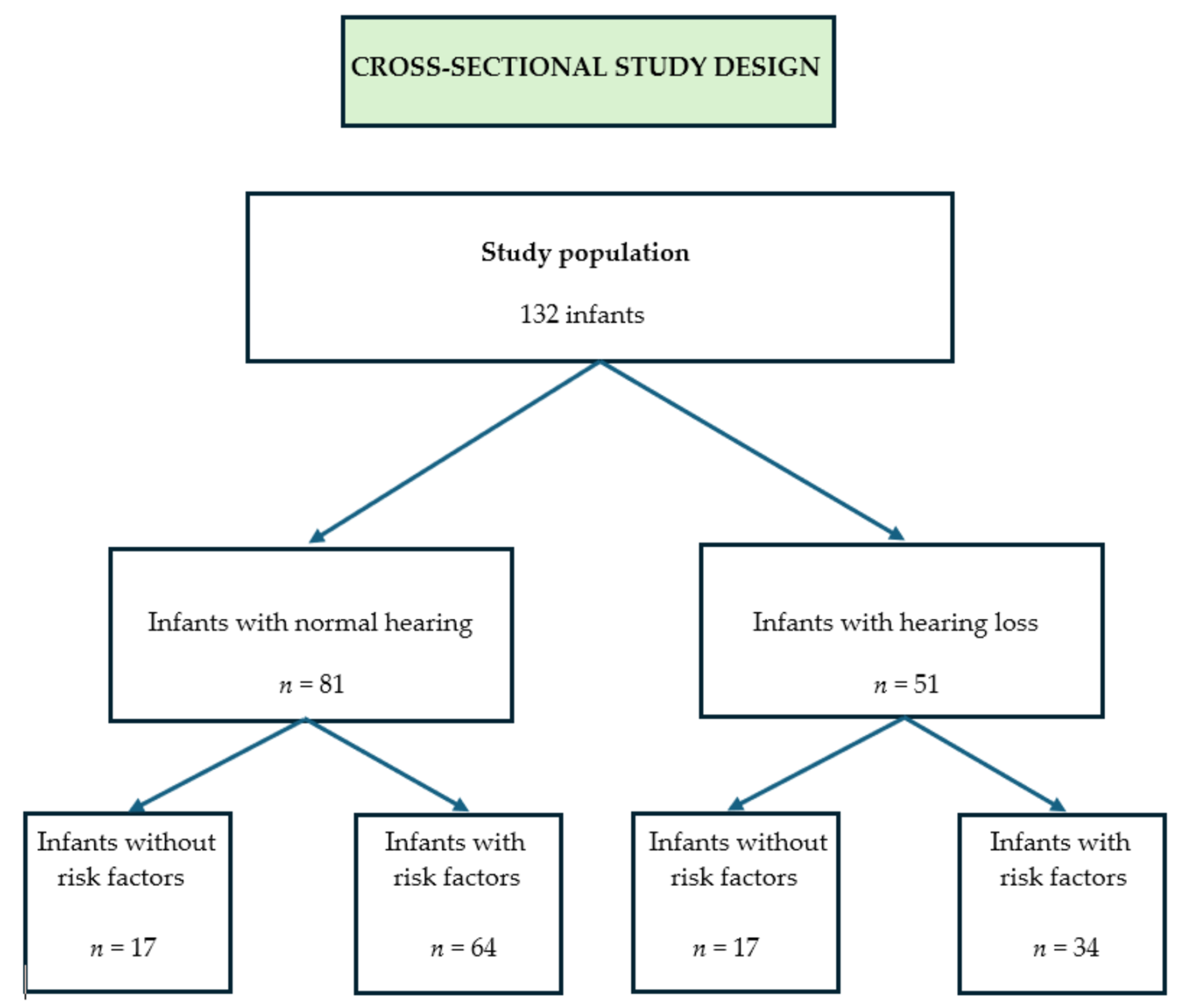

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Inclusion and Esclusion Criteria

2.3. Audiological and Phonology Evaluation

2.4. Instrument and Administration

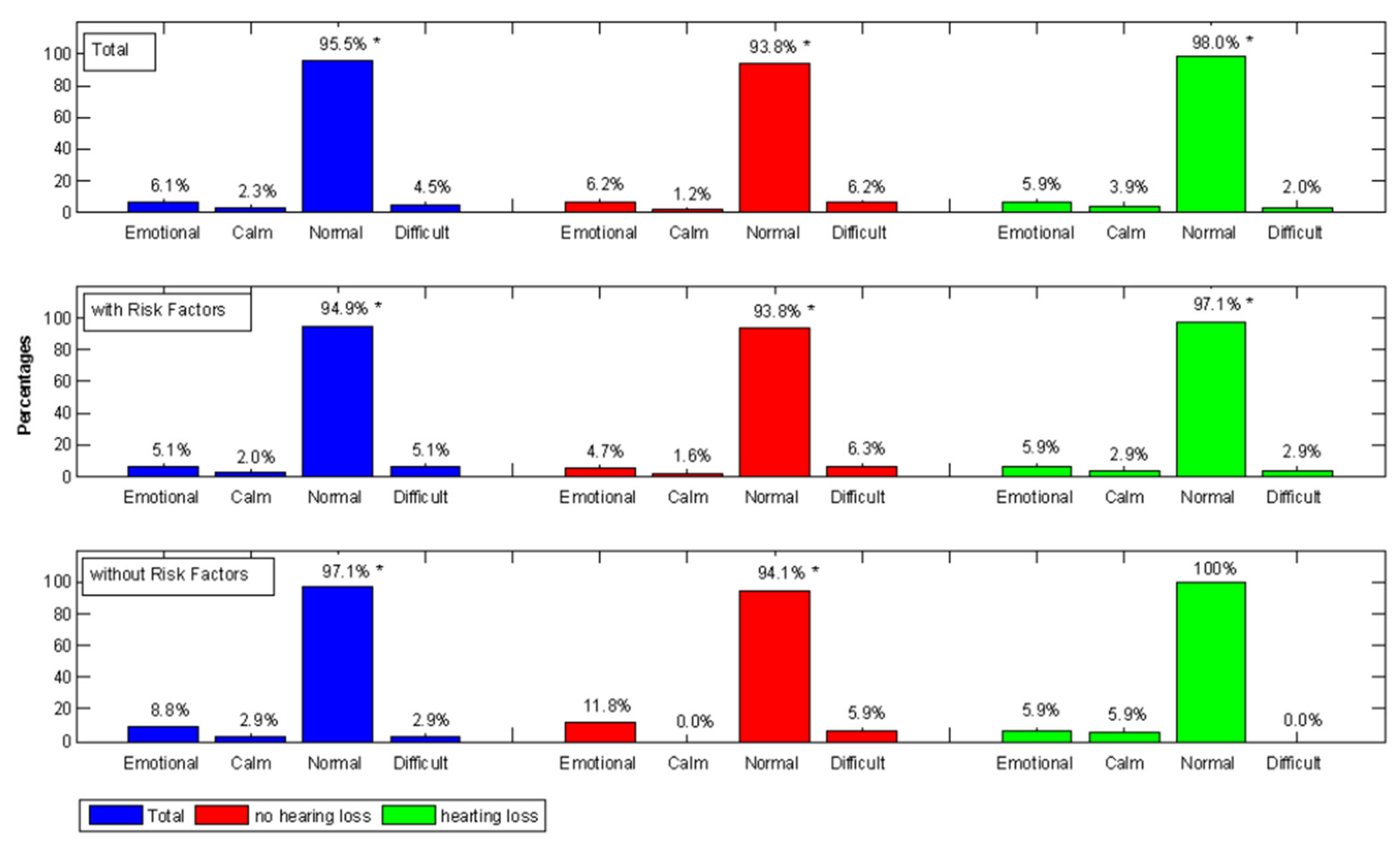

- Emotional temperament, with high emotional responsiveness, both positive and negative (child usually described as lively).

- Calm temperament, with low emotional responsiveness, both positive and negative (child who smiles little).

- Normal temperament, with greater positive reactivity than negative reactivity (sunny and positive child).

- Difficult temperament, with a negative reactivity greater than the positive one (child easily irritable, mostly sad or defined as unmanageable).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Parents’ Work and Education Level in the Evaluation of the Infant Temperament Using the QUIT Questionnaire

4.2. Influence of the Infant’s Age and Degree of Hearing Loss on Temperament

4.3. Influence of Risk Factors on Temperament

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RF | Risk factors |

| QUIT | Italian Temperament Questionnaire |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| ABR | Auditory-evoked brainstem |

References

- Allport Gordon, W. Personality: A Psychological Interpretation; Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro, J.A.; Hodgson, D.M.; Costigan, K.A.; Johnson, T.R. Fetal Antecedents of Infant Temperament. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 2568–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axia, G. QUIT. Questionari Italiani del Temperamento; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2002; pp. 7–103. [Google Scholar]

- Maltby, L.E.; Callahan, K.L.; Friedlander, S.; Shetgiri, R. Infant Temperament and Behavioral Problems: Analysis of High-Risk Infants in Child Welfare. J. Public Child Welf. 2019, 13, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeller, M.P.; Tomblin, J.B. An Introduction to the Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss Study. Ear Hear. 2015, 36 (Suppl. 1), 4S–13S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, W.C.; Li, D.; Dye, T.D.V. Influence of Hearing Loss on Child Behavioral and Home Experiences. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slot, P.L.; von Suchodoletz, A. Bidirectionality in preschool children’s executive functions and language skills: Is one developing skill the better predictor of the other? Early Child. Res. Q. 2018, 42, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibbe, L.E.; Montroy, J.J.; Bowles, R.P.; Morrison, F.J. Self-regulation and the Development of Literacy and Language Achievement from Preschool through Second Grade. Early Child. Res. Q. 2019, 46, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usai, M.C.; Garello, V.; Viterbori, P. Temperamental profiles and linguistic development: Differences in the quality of linguistic production in relation to temperament in children of 28 months. Infant Behav. Dev. 2009, 32, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BIAP. Recommendation nº 02/1 Bis. Audiometric Classification of Hearing Impairments. BIAP—International Bureau for Audio Phonology. 1996. Available online: https://www.biap.org/en/recommandations/recommendations/tc-02-classification/213-rec-02-1-en-audiometric-classification-of-hearing-impairments/file (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Tharpe, A.M.; Sladen, D.P.; Dodd-Murphy, J.; Boney, S.J. Minimal hearing loss in children: Minimal but not inconsequential. In Seminars in Hearing; Thieme Medical Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 30, pp. 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos, I.; Houston, D.M. Temperament in Toddlers with and Without Prelingual Hearing Loss. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2024, 67, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montirosso, R.; Cozzi, P.; Trojan, S.; Bellù, R.; Zanini, R.; Borgatti, R. Temperamental style in preterms and full-terms aged 6–12 months of age. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2005, 31, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Perricone, G.; Morales, M.R. The temperament of preterm infant in preschool age. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2011, 37, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassiano, R.G.M.; Provenzi, L.; Linhares, M.B.M.; Gaspardo, C.M.; Montirosso, R. Does preterm birth affect child temperament? A meta-analytic study. Infant Behav. Dev. 2020, 58, 101417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caravale, B.; Sette, S.; Cannoni, E.; Marano, A.; Riolo, E.; Devescovi, A.; De Curtis, M.; Bruni, O. Sleep Characteristics and Temperament in Preterm Children at Two Years of Age. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lean, R.E.; Smyser, C.D.; Rogers, C.E. Assessment: The Newborn. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 26, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Temperamental Profile | Positive Emotionality | Negative Emotionality |

|---|---|---|

| emotional | ↑ | ↑ |

| calm | ↓ | ↓ |

| normal | ↑ | ↓ |

| difficult | ↓ | ↑ |

| Parameters | Total | Group 1: No Hearing Loss | Group 2: Hearing Loss | Group 1 vs. Group 2 p-Value (Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | 132 | 61.4% (81) | 38.6% (51) | |

| Age at admission | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 5.4 ± 3.9 | 4.5 ± 2.0 | 5.5 ± 3.5 | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) | 5.0 (3.0, 7.0) | 0.35 (MW) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 62.1% (82) | 61.7% (50) | 62.7% (32) | 0.91 (C) |

| Female | 37.9% (50) | 38.3% (31) | 37.3% (19) | |

| Infants with risk factors | 74.2% (98) | 79.0% (64) | 66.7% (34) | 0.11 (C) |

| Prenatal infection | 19.7% (26) | 23.5% (19) | 13.7% (7) | 0.17 (C) |

| Ear malformation | 3.8% (5) | 2.5% (2) | 5.9% (3) | 0.37 (F) |

| Genetic syndrome | 3.8% (5) | 2.5% (2) | 5.9% (3) | 0.37 (F) |

| Hypoacoustic familiarity | 9.1% (12) | 2.5% (2) | 19.6% (10) | 0.0013 * (F) |

| Intensive care | 45.5% (60) | 58.0% (47) | 25.5% (13) | 0.0003 * (C) |

| Days of intensive care | n = 47 | n = 13 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 22.4 ± 19.5 | 21.7 ± 17.2 | 25.2 ± 27.2 | |

| Median (IQR) | 16.5 (7.0, 30.0) | 18.0 (8.25, 29.5) | 15.0 (5.75, 40.25) | 0.61 (MW) |

| Parents | ||||

| Family members | n = 80 | n = 51 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 2.0) | |

| Mean rank | 66.4 | 65.3 | 0.85 (MW) | |

| Mother’s profession | ||||

| No response | 0.8% (1) | 1.2% (1) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Unemployed | 52.3% (69) | 50.6% (41) | 54.9% (28) | |

| Student | 1.5% (2) | 1.2% (1) | 2.0% (1) | 0.41 (F) |

| Housewife | 3.0% (4) | 3.7% (3) | 2.0% (1) | |

| Freelance | 15.9% (21) | 12.3% (10) | 21.6% (11) | |

| Employee | 26.5% (35) | 30.9% (25) | 19.6% (10) | |

| Father’s profession | ||||

| No response | 3.0% (4) | 4.9% (4) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Unemployed | 10.6% (14) | 7.4% (6) | 15.7% (8) | |

| Freelance | 24.2% (32) | 23.5% (19) | 25.5% (13) | 0.35 (C) |

| Employee | 62.1% (82) | 64.2% (52) | 58.8% (30) | |

| Mother’s education level | ||||

| No response | 0.8% (1) | 1.2% (1) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Primary school diploma | 4.5% (6) | 3.7% (3) | 5.9% (3) | |

| Middle school diploma | 30.3% (40) | 27.2% (22) | 35.3% (18) | 0.63 (F) |

| High school diploma | 34.1% (45) | 34.6% (28) | 33.3% (17) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 30.3% (40) | 33.3% (27) | 25.5% (13) | |

| Father’s education level | ||||

| No response | 3.0% (4) | 4.9% (4) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Primary school diploma | 3.0% (4) | 4.9% (4) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Middle school diploma | 24.2% (32) | 23.5% (19) | 25.5% (13) | 0.52 (F) |

| High school diploma | 53.0% (70) | 50.6% (41) | 56.9% (29) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 16.7% (22) | 16.0% (13) | 17.6% (9) | |

| Care by grandparents | 15.2% (20) | 17.3% (14) | 11.8% (6) | 0.74 (C) |

| Care by parents | 99.2% (131) | 98.8% (80) | 100% (51) | 1.0 (F) |

| QUIT Questionnaire | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Total | Group 1: No Hearing Loss | Group 2: Hearing Loss | Group 1 vs. Group 2 p-Value (Test) |

| Infants | 132 | 38.6% (51) | 61.4% (81) | |

| Social orientation score | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 0.16 (T) |

| Median (IQR) | 4.8 (4.3, 5.3) | 4.9 (4.4, 5.3) | 4.7 (4.1, 5.3) | |

| Novelty Inhibition score | n = 77 | n = 50 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.1 (1.5, 2.6) | 2.1 (1.5, 2.6) | 2.0 (1.6, 2.5) | 0.63 (MW) |

| Motor Activity score | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 0.73 (T) |

| Median (IQR) | 3.8 (3.2, 4.5) | 3.7 (3.2, 4.3) | 3.9 (3.2, 4.6) | |

| Positive Emotionality score | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 5.0 ± 0.9 | |

| Median (IQR) | 5.1 (4.6, 5.7) | 5.1 (4.6, 5.6) | 5.2 (4.5, 5.7) | 0.96 (MW) |

| Negative Emotionality score | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.6 (2.1, 3.0) | 2.6 (2.1, 3.0) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.1) | 0.47 (MW) |

| Attention score | n = 131 | n = 80 | n = 51 | |

| Mean ± SD | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.6 (4.1, 5.1) | 4.6 (4.2, 5.2) | 4.6 (4.0, 5.0) | 0.26 (MW) |

| Parameters | Group 1A: No Hearing Loss and Without Risk Factors | Group 2A: Hearing Loss and Without Risk Factors | Group 1A vs. Group 2A p-Value (Test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | 21.0% (17/81) | 33.3% (17/51) | |

| Age at admission | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.6 ± 3.2 | 5.1 ± 4.8 | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0, 6.5) | 3.0 (2.75, 6.25) | 0.92 (MW) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 47.1% (8) | 64.7% (11) | 0.30 (C) |

| Female | 52.9% (9) | 35.3% (6) | |

| Parents | |||

| Family members | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | |

| Mean rank | 17.5 | 17.5 | 1.0 (MW) |

| Mother’s profession | |||

| No response | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Unemployed | 47.1% (8) | 35.3% (6) | |

| Student | 5.9% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 0.62 (F) |

| Housewife | 5.9% (1) | 5.9% (1) | |

| Freelance | 17.6% (3) | 41.2% (7) | |

| Employee | 23.5% (4) | 17.6% (3) | |

| Father’s profession | |||

| No response | 5.9% (1) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Unemployed | 5.9% (1) | 11.8% (2) | 1.0 (F) |

| Freelance | 29.4% (5) | 35.3% (6) | |

| Employee | 58.8% (10) | 52.9% (9) | |

| Mother’s education level | |||

| No response | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Primary school diploma | 5.9% (1) | 5.9% (1) | 0.95 (F) |

| Middle school diploma | 29.4% (5) | 29.4% (5) | |

| High school diploma | 41.2% (7) | 29.4% (5) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 23.5% (4) | 35.3% (6) | |

| Father’s education level | |||

| No response | 5.9% (1) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Primary school diploma | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 0.89 (F) |

| Middle school diploma | 29.4% (5) | 23.5% (4) | |

| High school diploma | 47.1% (8) | 58.8% (10) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 17.6% (3) | 17.6% (3) | |

| Care by grandparents | 17.6% (3) | 5.9% (1) | 0.60 (F) |

| Care by parents | 100% (17) | 100% (17) | 1.0 (F) |

| QUIT Questionnaire | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Temperament Dimensions | Group 1A: No Hearing Loss and Without Risk Factors | Group 2A: Hearing Loss and Without Risk Factors | Group 1A vs. Group 2A p-Value (Test) |

| Infants | 21.0% (17/81) | 33.3% (17/51) | |

| Social orientation score | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 4.8 ± 1.0 | 0.93 (T) |

| Median (IQR) | 5.1 (4.5, 5.5) | 4.9 (3.8, 5.5) | |

| Novelty Inhibition score | n = 16 | n = 17 | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 0.96 (T) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.5) | 2.0 (1.6, 2.3) | |

| Motor Activity score | |||

| Mean ± SD | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 0.58 (T) |

| Median (IQR) | 3.7 (3.2, 4.0) | 3.4 (2.9, 4.1) | |

| Positive Emotionality score | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.9± 1.2 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 0.61 (T) |

| Median (IQR) | 5.1 (4.9, 5.6) | 5.4 (4.6, 5.7) | |

| Negative Emotionality score | |||

| Mean ± SD | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.7 (2.4, 2.9) | 2.6 (1.8, 2.8) | 0.25 (MW) |

| Attention score | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.4 ± 1.1 | 4.5 ± 0.8 | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.4 (4.1, 5.3) | 4.4 (4.1, 5.3) | |

| Mean rank | 17.5 | 17.5 | 1.0 (MW) |

| Parameters | Group 1B No Hearing Loss and Risk Factors | Group 2B Hearing Loss and Risk Factors | Group 1B vs. Group 2B p-Value (Test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | 79.0% (64/81) | 66.7% (34/51) | |

| Age at admission | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.5 ± 1.6 | 5.7 ± 2.7 | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 5.0 (3.0, 7.0) | 0.07 (MW) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 34.4% (42) | 61.8% (21) | 0.14 (C) |

| Female | 65.6% (22) | 38.2% (13) | |

| Prenatal infection | 29.7% (19) | 20.6% (7) | 0.94 (C) |

| Ear malformation | 3.1% (2) | 8.8% (3) | 0.34 (F) |

| Genetic syndrome | 3.1% (2) | 8.8% (3) | 0.34 (F) |

| Hypoacoustic familiarity | 3.1% (2) | 29.4% (10) | 0.0003 * (F) |

| Intensive care | 71.9% (46) | 38.2% (13) | 0.0012 * (C) |

| Days of intensive care | n = 46 | n = 13 | |

| Mean ± SD | 22.1 ± 17.1 | 25.2 ± 27.2 | |

| Median (IQR) | 19.0 (9.0,30.0) | 15.0 (5.75, 40.25) | 0.53 (MW) |

| Parents | |||

| Family members | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 2.0) | |

| Mean rank | 49.2 | 48.6 | 0.91 (MW) |

| Mother’s profession | |||

| No response | 1.6% (1) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Unemployed | 51.6% (33) | 64.7% (22) | 0.35 (F) |

| Student | 0.0% (0) | 2.9% (1) | |

| Housewife | 3.1% (2) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Freelance | 10.9% (7) | 11.8% (4) | |

| Employee | 32.8% (21) | 20.6% (7) | |

| Father’s profession | |||

| No response | 4.7% (3) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Unemployed | 7.8% (5) | 17.6% (6) | 0.38 (F) |

| Freelance | 21.9% (14) | 20.6% (7) | |

| Employee | 65.6% (42) | 61.8% (21) | |

| Mother’s education level | |||

| No response | 1.6% (1) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Primary school diploma | 3.1% (2) | 5.9% (2) | 0.48 (F) |

| Middle school diploma | 26.6% (17) | 38.2% (13) | |

| High school diploma | 32.8% (21) | 32.4% (11) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 35.9% (23) | 23.5% (8) | |

| Father’s education level | |||

| No response | 4.7% (3) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Primary school diploma | 6.2% (4) | 0.0% (0) | 0.59 (F) |

| Middle school diploma | 21.9% (14) | 25.6% (9) | |

| High school diploma | 51.6% (33) | 55.9% (19) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 15.6% (10) | 17.6% (6) | |

| Care by grandparents | 17.2% (11) | 14.7% (5) | 0.75 (C) |

| Care by parents | 98.4% (63) | 100% (34) | 1.0 (F) |

| Temperament Dimensions | Group 1B No Hearing Loss and Risk Factors | Group 2B Hearing Loss and Risk Factors | Group 1B vs. Group 2B p-Value (Test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social orientation score | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 0.054 (T) |

| Median (IQR) | 4.9 (4.4, 5.3) | 4.7 (4.2, 5.0) | |

| Novelty Inhibition score | n = 61 | n = 33 | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 0.86 (T) |

| Median (IQR) | 2.2 (1.6, 2.6) | 2.0 (1.6, 2.6) | |

| Motor Activity score | |||

| Mean ± SD | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 4.2 ± 0.9 | 0.054 (T) |

| Median (IQR) | 3.8 (3.2, 4.3) | 4.3 (3.7, 4.7) | |

| Positive Emotionality score | |||

| Mean ± SD | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | |

| Median (IQR) | 5.1 (4.6, 5.7) | 5.1 (4.3, 5.6) | 0.72 (MW) |

| Negative Emotionality score | |||

| Mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.6 (2.1, 3.1) | 2.4 (2.0, 3.1) | 0.95 (MW) |

| Attention score | n = 63 | n = 34 | |

| Mean ± SD | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.6 (4.2, 5.1) | 4.5 (4.0, 4.9) | 0.22 (MW) |

| QUIT Dimensions | Hearing Loss Degree | p-Value (Test) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total † | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Profound | ||

| Total children with hearing loss † | n = 51 | n = 12 | n = 20 | n = 8 | n = 11 | |

| Emotional temperament | 5.9% (3) | 8.3% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 12.5% (1) | 9.1% (1) | 0.12 (F) |

| Calm temperament | 3.9% (2) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 12.5% (1) | 9.1% (1) | |

| Normal temperament | 98% (50) | 100% (12) | 100% (20) | 87.5% (7) | 100% (11) | |

| Difficult temperament | 2.0% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 12.5% (1) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Hearing loss with R.F † | n = 34 | n = 9 | n = 11 | n = 5 | n = 9 | |

| Emotional temperament | 5.9% (2) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 20% (1) | 11.1% (1) | |

| Calm temperament | 2.9% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 11.1% (1) | 0.12 (F) |

| Normal temperament | 97.1% (33) | 100% (9) | 100% (11) | 80% (4) | 100% (9) | |

| Difficult temperament | 2.9% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 20% (1) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Hearing loss without R.F † | n = 17 | n = 3 | n = 9 | n = 3 | n = 2 | |

| Emotional temperament | 5.9% (1) | 33.3% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | |

| Calm temperament | 5.9% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 33.3% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 0.27 (F) |

| Normal temperament | 100% (17) | 100% (3) | 100% (9) | 100% (3) | 100% (2) | |

| Difficult temperament | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laria, C.; Malesci, R.; Mallardo, A.; Landolfi, E.; D’Ambrosio, F.G.; Auletta, G.; Serra, N.; Fetoni, A.R. Temperament Development During the First Year of Life in a Sample of Patients with Hearing Impairment Who Participated in the Infants Screening Program in a Single Center in Southern Italy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2025, 12, 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091172

Laria C, Malesci R, Mallardo A, Landolfi E, D’Ambrosio FG, Auletta G, Serra N, Fetoni AR. Temperament Development During the First Year of Life in a Sample of Patients with Hearing Impairment Who Participated in the Infants Screening Program in a Single Center in Southern Italy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children. 2025; 12(9):1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091172

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaria, Carla, Rita Malesci, Antonietta Mallardo, Emma Landolfi, Federica Geremicca D’Ambrosio, Gennaro Auletta, Nicola Serra, and Anna Rita Fetoni. 2025. "Temperament Development During the First Year of Life in a Sample of Patients with Hearing Impairment Who Participated in the Infants Screening Program in a Single Center in Southern Italy: A Cross-Sectional Study" Children 12, no. 9: 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091172

APA StyleLaria, C., Malesci, R., Mallardo, A., Landolfi, E., D’Ambrosio, F. G., Auletta, G., Serra, N., & Fetoni, A. R. (2025). Temperament Development During the First Year of Life in a Sample of Patients with Hearing Impairment Who Participated in the Infants Screening Program in a Single Center in Southern Italy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children, 12(9), 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091172