The Attachment Process of the Mothers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Pre-School Years: A Mixed Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.1.1. Quantitative Phase

2.1.2. Qualitative Phase

2.2. Participants

2.3. Research Instruments

2.3.1. Maternal Attachment Measurement Tool

2.3.2. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS)

2.3.3. General Characteristics

2.3.4. The In-Depth Interview Questions

2.4. Data Collection Methods and Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis Methods

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. First Phase of the Study: Level of Attachment in Mothers of Children with ASD

3.1.1. General Characteristics of Mothers and Children with ASD

3.1.2. Degree of Attachment in Mothers of Children with ASD

3.1.3. Attachment Level According to General Characteristics of Mothers and Children with ASD

3.2. Second Phase of the Study: Level of Attachment in Mothers of Children with ASD

3.2.1. General Characteristics of In-Depth Interview Participants and Their Children with ASD

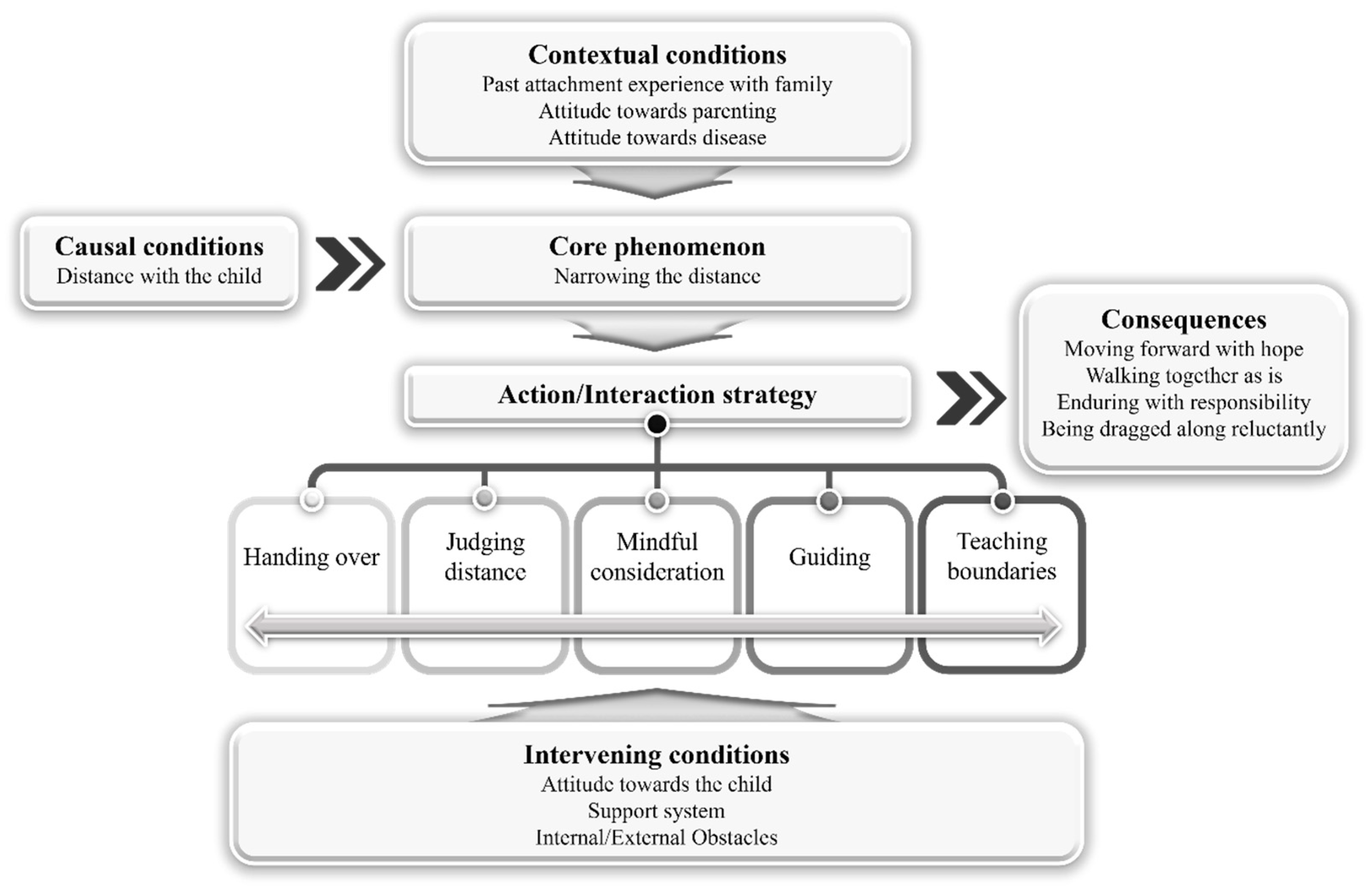

3.2.2. Paradigm Model of Attachment in Mothers of Children with ASD

Causal Conditions

Core Phenomenon

Contextual Conditions

Intervening Conditions

Action/Interaction Strategies

Consequences

Core Category: Narrowing the Distance and Continuing the Connection

3.3. Attachment Process of Mothers of Children with ASD

3.3.1. Stages in the Attachment Process of Mothers of Children with ASD

- (1).

- Confusion phase begins when mothers perceive the differences in their children with ASD and confirm the diagnosis. As mothers increasingly realize that their children are different from others, they become overwhelmed with various emotions. They struggle to believe the situation, feel uncertain about what to do, and where to place their feelings, leading to growing despair.

- (2).

- Exploration phase is when participants gauge the distance with their children and seek to get closer by examining and observing themselves, their children with ASD, and the surrounding environment. Through this observation, they broaden their interest in the child. In this phase, strategies primarily used include seeking information, attempting multi-faceted exploration, and employing internal regulation to measure the distance.

- (3).

- Close immersion phase is when participants focus on narrowing the distance with their children by continuously checking, understanding, and reducing the child’s resistance. In this phase, participants predominantly experience positive emotions towards the child, and the increased interest in the child gained during the exploration phase further amplifies these positive feelings. The strategies primarily used in this phase include providing stability and empathy, encompassed within the broader strategy of mindful consideration.

- (4).

- Active engagement phase is the most active and proactive stage in attempting to narrow the distance with children with ASD. During this phase, participants have the strongest will to promote the child’s growth using guiding strategies. Additionally, this phase is most influenced by the mother’s attitude towards the child. The more positively the mother perceives the child’s responses, the more active this phase becomes.

- (5).

- Perceptual exchange phase is when mothers firmly perceive that some communication is occurring with their children with ASD. Mothers are confident in the responsiveness of the child to their expressions and actions. This phase is heavily influenced by the child’s functional level and improvement, as well as the mother’s sensitivity to the child. As mothers approach the stabilization phase, their positive feelings towards the child peak, leading to increased trust in the child.

- (6).

- Stabilization phase is when participants establish a close and stable relationship with their children due to the narrowed distance. Participants feel comfortable in their relationship with the child and experience a sense of identification with the child, perceiving the child as a precious presence. In this phase, they observe the child’s growth and express hope for further improvement.

- (7).

- Stagnation phase is characterized by settling into the current situation, employing strategies to teach boundaries. Participants do not harbor hopes or expectations for significant improvements in the child’s functional abilities. In this phase, participants express considerable concern and fear about the child’s uncertain future, which justifies the stagnation in their efforts to narrow the distance. This concern and fear act as a rationale for the stagnation in their efforts to further reduce the distance between themselves and their child.

- (8).

- Detachment phase is characterized by a significant lack of attempts to narrow the distance with the child, with the distance gradually widening. Participants experience feelings of depression, distress, sadness, anger, and despair regarding their current situation and express anxiety and fear about the child’s future.

3.3.2. Process in the High and Low Attachment Score Group

3.3.3. Attachment Types of Mothers of Children with ASD

4. Discussion

4.1. Attachment Levels of Mothers with Children on the ASD

4.2. Attachment Process and Types in Mothers of Preschool-Aged Children with ASD

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S.N. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, E.; Cummings, E.M. A secure base from which to explore close relationships. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR™, 5th ed.; (Text Revision); American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022; pp. 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.J.; Paul, R.; Volkmar, F.R. Issues in the classification of pervasive developmental disorders and associated conditions. In Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders; Cohen, D.J., Donnellan, A.M., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 20–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kanner, L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv. Child 1943, 2, 217–250. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, G.; Lewy, A. Arousal, attention, and the socioemotional impairments of individuals with autism. In Autism: Nature, Diagnosis, and Treatment; Dawson, G., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Capps, L.; Sigman, M.; Mundy, P. Attachment security in children with autism. Dev. Psychopathol. 1994, 6, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzadzinski, R.L.; Luyster, R.; Spencer, A.G.; Lord, C. Attachment in young children with autism spectrum disorders: An examination of separation and reunion behaviors with both mothers and fathers. Autism 2014, 18, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koren-Karie, N.; Oppenheim, D.; Dolev, S.; Yirmiya, N. Mothers of securely attached children with autism spectrum disorder are more sensitive than mothers of insecurely attached children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutgers, A.H.; Van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Swinkels, S.H.N.; van Daalen, E.; Dietz, C.; Naber, F.B.A.; Buitelaar, J.K.; van Engeland, H. Autism, attachment and parenting: A comparison of children with autism spectrum disorder, mental retardation, language disorder, and non-clinical children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2007, 35, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Teague, S.J.; Gray, K.M.; Tonge, B.J.; Newman, L.K. Attachment in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2017, 35, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, E.J.; Hinkley, L.B.; Hill, S.S.; Nagarajan, S.S. Sensory processing in autism: A review of neurophysiologic findings. Pediatr. Res. 2011, 69, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauder, K.B.; Bennetto, L. Toward an Interdisciplinary Understanding of Sensory Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Integration of the Neural and Symptom Literatures. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotti, M.; de Falco, S. Attachment and autism spectrum disorder (without intellectual disability) during middle childhood: In search of the missing piece. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 662024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, D.B.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Ing, S.; MacCulloch, R.; Roberts, W.; McKeever, P.; McMorris, C.A. Live it to understand it: The experiences of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senju, A.; Johnson, M.H. Atypical eye contact in autism: Models, mechanisms and development. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2009, 33, 1204–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, M.; Guerriero, V.; Zavattini, G.C.; Petrillo, M.; Racinaro, L.; Bianchi di Castelbianco, F. Parental attunement, insightfulness, and acceptance of child diagnosis in parents of children with autism: Clinical implications. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.J.; Glenwick, D.S. Correlates of attachment perceptions in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 2056–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, A. Mentalizing the unmentalizable: Parenting children on the spectrum. J. Infant Child Adolesc. Psychother. 2009, 8, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, B.; Dallos, R.; Stancer, R. Feeling ‘like you’re on … a prison ship’—Understanding the caregiving and attachment narratives of parents of autistic children. Hum. Syst. 2021, 1, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.D.; Sweeney, D.P.; Hodge, D.; Lopez-Wagner, M.C.; Looney, L. Parenting stress and closeness: Mothers of typically developing children and mothers of children with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2009, 24, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.B. An Effect of the mother-child attachment promotion program for the child with pervasive developmental disorder. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2000, 30, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, B.M.; Newman, L.K.; Gray, K.M.; Rinehart, N.J. Parents of Children with ASD Experience More Psychological Distress, Parenting Stress, and Attachment-Related Anxiety. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 2979–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, R.; Dallos, R. Autism and attachment difficulties: Overlap of symptoms, implications and innovative solutions. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabekiroglu, K.; Rodopman-Arman, A. Parental attachment style and severity of emotional/behavioral problems in toddlerhood. Noropsikiyatri Ars. 2011, 48, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, D.; Koren-Karie, N.; Dolev, S.; Yirmiya, N. Maternal insightfulness and resolution of the diagnosis are associated with secure attachment in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Rutgers, A.H.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Swinkels, S.H.; van Daalen, E.; Dietz, C.; Naber, F.B.; Buitelaar, J.K.; van Engeland, H. Parental sensitivity and attachment in children with autism spectrum disorder: Comparison with children with mental retardation, with language delays, and with typical development. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seskin, L.; Feliciano, E.; Tippy, G.; Yedloutschnig, R.; Sossin, K.M.; Yasik, A. Attachment and autism: Parental attachment representations and relational behaviors in the parent-child dyad. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.J. A Study on Mother’s Attachment to Her Infant: Development and Validation of Korean Maternal Attachment Inventory. Ph.D. Thesis, Korea University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2006. Available online: https://www.riss.kr/link?id=T10460482 (accessed on 1 March 2015).

- Schopler, E.; Reichler, R.J.; Renner, B.R. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale; Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.; Park, L. Childhood Autism Rating Scale; Special Education: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S.J.; Hwang, J.S.; Shin, A.L.; Kim, J.Y.; Bae, S.M.; Sheehy-Knight, J.; Kim, J.W. Accuracy of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyl, D.D.; Newland, L.A.; Freeman, H. Predicting preschoolers’ attachment security from parenting behaviours, parents’ attachment relationships and their use of social support. Early Child Dev. Care 2008, 180, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Smith, C.L. Longitudinal bidirectional relations between children’s negative affectivity and maternal emotion expressivity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 983435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxton-Kane, M.; Slade, P. The role of maternal prenatal attachment in a woman’s experience of pregnancy and implications for the process of care. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2002, 20, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.F.; Ettinger, A.K.; Mendelson, T.; Le, H.N. Prenatal depression predicts postpartum maternal attachment in low-income Latina mothers with infants. Infant Behav. Dev. 2011, 34, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachimori, H.; Osada, H.; Kurita, H. Childhood autism rating scale—Tokyo version for screening pervasive developmental disorders. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2003, 57, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naber, F.B.A.; Swinkels, S.H.N.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Dietz, C.; van Daalen, E.; van Engeland, H. Attachment in Toddlers with Autism and Other Developmental Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007, 37, 1123–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beurkens, N.M.; Hobson, J.A.; Hobson, R.P. Autism severity and qualities of parent-child relations. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppenheim, D.; Koren-Karie, N.; Dolev, S.; Yirmiya, N. Maternal sensitivity mediates the link between maternal insightfulness/resolution and child-mother attachment: The case of children with autism spectrum disorder. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2012, 14, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesande, S.; Steegmans, D.; Maes, B. Parents’ views on facilitating and inhibiting factors in the development of attachment relationships with their children with severe disabilities. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2023, 40, 600–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, G.; Choe, J. A study of the identity as a mother of Vietnamese married immigrant and children’s attachment. Trans. Anal. Psychosoc. Ther. 2010, 7, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.M.; Park, H.J. Relationship among emotional clarity, maternal identity, and fetal attachment in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2017, 23, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, D.B.; MacCulloch, R.; Roberts, W.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; McKeever, P. Tensions in maternal care for children, youth, and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2020, 7, 2333393620907588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, N.H.; Norris, K.; Quinn, M.G. The factors predicting stress, anxiety and depression in the parents of children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 3185–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, N.; Kitagawa, M.; Iwamoto, S.; Kishimoto, T. Effects of an attachment-based parent intervention on mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder: Preliminary findings from a non-randomized controlled trial. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2021, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, D.; Seung, H.; Elder, J. Intervention Efficacy of Mother Training on Social Reciprocity for Children with Autism. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2005, 11, 444–455. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Z.; McPheeters, M.L.; Sathe, N.; Foss-Feig, J.H.; Glasser, A.; Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. A systematic review of early intensive intervention for autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e1303–e1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutstein, S.E.; Whitney, T. Asperger syndrome and the development of social competence. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2022, 17, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Kim, B.S. The structural relationships of social support, mother’s psychological status, and maternal sensitivity to attachment security in children with disabilities. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2009, 10, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N (%) | M ± SD | t or F | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers (n = 64) | Planned Pregnancy | Yes | 41 (64.1) | 209.23 ± 19.88 | 4.39 | <0.001 |

| No | 23 (35.9) | 183.78 ± 26.34 | ||||

| Age | 30–34 years | 17 (26.6) | 196.71 ± 24.66 | 2.36 | 0.081 | |

| 35–39 years | 34 (53.1) | 196.41 ± 26.61 | ||||

| 40–44 years | 11 (17.2) | 218.55 ± 20.09 | ||||

| ≥45 years | 2 (3.1) | 199.50 ± 13.44 | ||||

| Marital Status | Married | 63 (98.4) | ||||

| Widowed | 1 (1.6) | |||||

| Religion | Christianity | 30 (46.9) | 200.70 ± 24.02 | 0.59 | 0.623 | |

| Catholicism | 15 (23.4) | 204.40 ± 19.59 | ||||

| Buddhism | 1 (1.6) | 171.00 | ||||

| None | 18 (28.1) | 198.17 ± 32.92 | ||||

| Education Level | High school | 5 (7.8) | 209.60 ± 34.82 | 0.35 | 0.710 | |

| College | 46 (71.9) | 199.78 ± 24.85 | ||||

| Graduate school | 13 (20.3) | 199.00 ± 26.80 | ||||

| Employment Status | Employed | 28 (43.75) | 194.50 ± 27.49 | 1.64 | 0.107 | |

| Unemployed | 36 (56.25) | 204.97 ± 23.66 | ||||

| Number of Children | 1 | 25 (39.1) | ||||

| 2 | 36 (56.2) | |||||

| 3 | 2 (3.1) | |||||

| 5 | 1 (1.6) | |||||

| Children (n = 64) | Age | 3 years | 4 (6.2) | 208.75 ± 29.62 | 0.78 | 0.543 |

| 4 years | 14 (21.9) | 198.79 ± 30.16 | ||||

| 5 years | 23 (35.9) | 202.17 ± 21.67 | ||||

| 6 years | 11 (17.2) | 189.45 ± 32.00 | ||||

| 7 years | 12 (18.8) | 206.08 ± 20.45 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 53 (82.8) | 200.58 ± 26.10 | 0.13 | 0.896 | |

| Female | 11 (17.2) | 199.45 ± 25.08 | ||||

| Birth Order | First | 42 (65.6) | 200.50 ± 23.49 | 0.019 | 0.981 | |

| Second | 20 (31.3) | 199.85 ± 31.42 | ||||

| Third | 2 (3.1) | 203.50 ± 17.68 | ||||

| Age at Diagnosis (months) | ≤24 | 5 (7.8) | 211.20 ± 34.10 | 0.459 | 0.765 | |

| 24–36 | 29 (45.3) | 196.41 ± 24.75 | ||||

| 37–48 | 17 (26.6) | 203.00 ± 27.31 | ||||

| 49–60 | 9 (14.1) | 203.33 ± 18.66 | ||||

| ≥61 | 4 (6.2) | 198.00 ± 36.19 | ||||

| Content | Number of Items | Mean | Mean Item Rating (SD) | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Emotion | 11 | 46.91 | 4.26 (±0.44) | 33 | 55 |

| Seeking Contact | 7 | 30.13 | 4.30 (±0.23) | 20 | 35 |

| Self-Sacrificing Generosity | 10 | 36.25 | 3.63 (±0.64) | 23 | 48 |

| Proximity-Keeping Behavior | 4 | 16.25 | 4.06 (±0.10) | 9 | 20 |

| Protection | 5 | 20.50 | 4.10 (±0.20) | 14 | 25 |

| Unity (Cohesion) | 6 | 24.97 | 4.16 (±0.33) | 15 | 30 |

| Detachment | 4 | 10.17 | 2.54 (±0.40) | 4 | 20 |

| Expectation | 3 | 10.64 | 3.55 (±0.76) | 5 | 15 |

| total | 50 | 200.39 | 3.92 (±0.64) | 136 | 245 |

| Participant (n = 12) | Attachment Score | Age | Job | Education Level | Child’s Age | Child’s Gender | Birth Order | Diagnosis Age (Months) | Autism Severity | Interview Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Attachment Group | ||||||||||

| 1 | 241 | 40 | None | High school | 5 | Male | 1 | 27 | 33 | 3 |

| 2 | 230 | 31 | None | High school | 5 | Male | 2 | 45 | 24.5 | 1 |

| 3 | 237 | 34 | Yes | Graduate school | 4 | Male | 1 | 25 | 21 | 3 |

| 4 | 231 | 33 | Yes | Graduate school | 5 | Female | 1 | 38 | 32.5 | 2 |

| 5 | 245 | 42 | None | College | 4 | Male | 2 | 20 | 27.5 | 3 |

| 6 | 233 | 35 | Yes | College | 4 | Male | 1 | 36 | 22.5 | 2 |

| Low Attachment Group | ||||||||||

| 7 | 154 | 37 | Yes | College | 6 | Female | 1 | 65 | 30 | 1 |

| 8 | 169 | 39 | None | Graduate school | 7 | Female | 2 | 39 | 26.5 | 2 |

| 9 | 136 | 38 | Yes | College | 4 | Male | 2 | 32 | 47 | 3 |

| 10 | 169 | 37 | Yes | College | 5 | Male | 1 | 36 | 44 | 1 |

| 11 | 168 | 34 | None | College | 5 | Male | 2 | 40 | 34 | 2 |

| 12 | 171 | 35 | Yes | Graduate school | 3 | Male | 1 | 31 | 21 | 2 |

| Concept | Subcategory | Category | Paradigm Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniqueness, Slowness, Suspicion, Oddness, Regression | Perception of difference | Distance with the child | Causal conditions |

| Feeling lost, Unresponsiveness, Frustration, Closed-off, Lack of communication | Decreased reciprocity | ||

| Responsibility, Perception of motherly role | Maternal awareness | ||

| Lovable, Cute, Pitiful, Special, Precious, Pure, Trust | Special value to me | Narrowing the distance | Core phenomenon |

| Contact, Continuation, Immersion, Helping thoughts | Willingness to bond | ||

| Intimacy with the mother, Feelings of being loved, Sense of security, Resemblance, Reluctance to reverse, Feeling pushed away | Attachment perception with parents | Past attachment experience with family | Contextual conditions |

| Strong bond with siblings, Reliance on siblings | Intimacy with siblings | ||

| Guilt, Anticipation, Suddenness, Bewilderment | Perception of first meeting with child | Attitude towards parenting | |

| Sole responsibility for childcare, Decreased shared time, Separation from child, Auxiliary role | Closeness in childcare | ||

| Deviation, Strangeness, Sensitive child, Ease, Sleep deprivation, Extended work | Difficulty in parenting | ||

| Trust in recoverability, Perception of incurable disease, Recognition of limits | Disease perception | Attitude towards disease | |

| Taking it lightly, Vague reassurance | Carefree attitude | ||

| Natural reactions, Excessive contact, Child following, Increased child affection, Being used as a tool | Mother’s perception of child’s response | Attitude towards the child | Intervening conditions |

| Treatment avoiding permissiveness, Emotion-focused treatment | Core treatment direction | ||

| Husband’s compensation, Shared childcare, Support from non-disabled siblings, Parental help, Sibling support | Family support | Support system | |

| Helping hands, Support from friends | Social support | ||

| Husband’s criticism, Unconsoled, Indifference to child, Conflict with in-laws | Family conflicts | Internal/External obstacles | |

| Being sick, Caring for other children | Other care demands | ||

| Burden of others’ views, Criticism from others towards child | Negative perception from others | ||

| Unloving stereotypical expressions, Neglect, Muddle through | Passive handling | Handing over | Action/Interaction strategy |

| Seeking treatment information, Acquiring knowledge about illness, Sharing experiences | Information seeking | Judging distance | |

| Observing, Monitoring the child’s surroundings | Multi-faceted exploration | ||

| Self-reflection, Recognizing my emotions | Internal regulation | ||

| Being patient, Making the child comfortable | Providing stability | Mindful consideration | |

| Seeing as is, Reading emotions, Active listening | Empathy | ||

| Kissing, Stroking, Rubbing, Hugging | Contact | Guiding | |

| Providing stimulation, Praising, Following professional advice, Recognizing signals, Responding immediately | Active involvement | ||

| Spending time together, Engaging in community experiences | Being together | ||

| Being firm, Not allowing, Limiting demands | Setting firm standards | Teaching boundaries | |

| One body with one mind, Valuing, Seeing as a gift, A source of strength, Joy, Pride, Contentment | Precious existence | Moving forward with hope | Consequences |

| Feeling like a real mother, Confidence, Changing perception of disability, Hope | Raising one’s head | ||

| Increased expression of the child, Expanded expression of affection towards others, Emergence of new behaviors | Observing child’s growth | ||

| Gratitude for the present, Satisfaction with the child | Living a content life | Walking together as is | |

| Comfort, Stability, Relief | Sense of well-being | ||

| Destiny, Lifelong task, Acceptance | Seeing as fate | Enduring with responsibility | |

| Upset, Sadness, Anger, Anxiety, Despair, Uncertainty, Fear, Depression, Sense of disconnection | Emotional difficulties | Being dragged along reluctantly | |

| Pain all over, Sleeplessness, Feeling physically drained | Physical exhaustion | ||

| Withdrawal, Cutting off interactions with others, Feeling comfortable in unfamiliar places, Hiding child’s disability, Reluctance to go out | Social isolation |

| Type | High Attachment Score Group | Low Attachment Score Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Immersion | Grateful Contentment | Responsibility— Centered | Passive Coping | |

| Participant | 1, 4, 6 | 2, 3, 5 | 7, 8, 10, 12 | 9, 11 |

| Causal Conditions | ||||

| Distance from Child | Exists | Exists | Exists | Exists |

| Perception of Difference | Exists | Exists | Exists | Exists |

| Reduced Reciprocity | More → Less | More → Less | More → Less | More |

| Maternal Awareness | More | More | More | Moderate |

| Core Phenomenon | ||||

| Narrowing the Distance | More | More | Less | Less |

| Contextual Conditions | ||||

| Past Attachment Experiences with Family | ||||

| Attachment Experience with Own Parents | High | High | Moderate to Low | Low |

| Attitude towards Parenting | ||||

| Perception of First Meeting with Child | Positive | Positive | Positive to Negative | Negative |

| Degree of Parenting Closeness | High | High | Moderate | Moderate to Low |

| Parenting Difficulties | More → Less | More → Less | More → Less | More |

| Attitude towards Illness | Positive | Positive to Moderate | Positive to Negative | Negative |

| Intervening Conditions | ||||

| Attitude towards Child | Positive | Positive | Moderate to Negative | Negative |

| Support System | High | High | High to Low | Low |

| Internal and External Obstacles | Few | Few | Many to Few | Many |

| Action/interaction strategies | Judging distance (Moderate to More) Mindful consideration (More) Guiding (More) | Judging distance (More) Mindful consideration (More) Guiding (More) | Guiding (Moderate) Teaching boundaries (More) | Handing over (More) |

| Consequences | moving forward with hope | walking together as is | enduring with responsibility | being dragged along reluctantly |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jung, M.; Han, K.S. The Attachment Process of the Mothers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Pre-School Years: A Mixed Methods Study. Children 2025, 12, 1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091169

Jung M, Han KS. The Attachment Process of the Mothers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Pre-School Years: A Mixed Methods Study. Children. 2025; 12(9):1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091169

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Miran, and Kuem Sun Han. 2025. "The Attachment Process of the Mothers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Pre-School Years: A Mixed Methods Study" Children 12, no. 9: 1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091169

APA StyleJung, M., & Han, K. S. (2025). The Attachment Process of the Mothers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Pre-School Years: A Mixed Methods Study. Children, 12(9), 1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091169