Parental Values During Tracheostomy Decision-Making for Their Critically Ill Child: Interviews of Parents Who Just Made the Decision †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

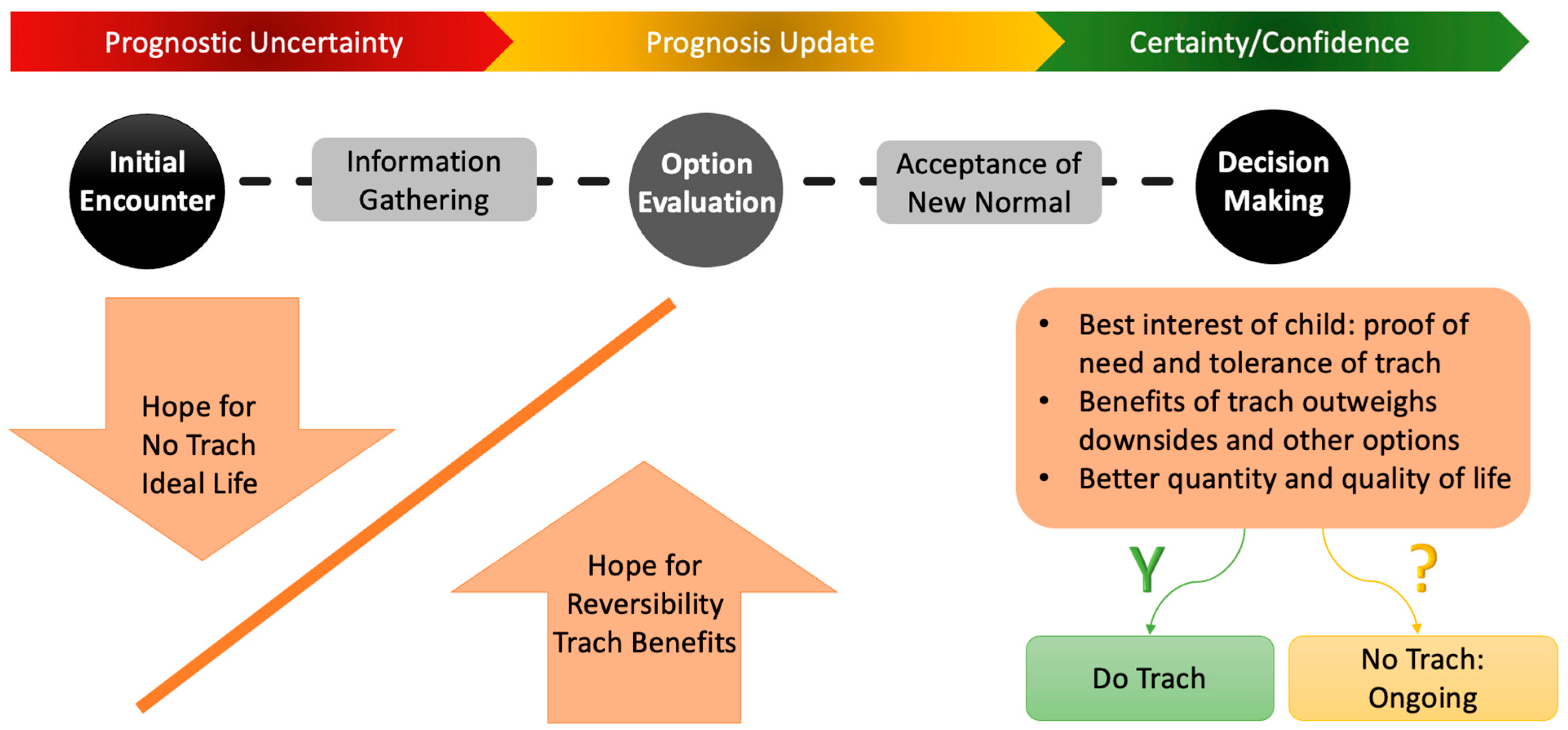

4. Discussion

5. Implications and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Interview Questions

References

- Gergin, O.; Adil, E.A.; Kawai, K.; Watters, K.; Moritz, E.; Rahbar, R. Indications of pediatric tracheostomy over the last 30 years: Has anything changed? Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 87, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nageswaran, S.; Golden, S.L.; Gower, W.A.; King, N.M.P. Caregiver perceptions about their decision to pursue tracheostomy for children with medical complexity. J. Pediatr. 2018, 203, 354–360.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageswaran, S.; Hurst, A.; Radulovic, A. Unexpected survivors: Children with life-limiting conditions of uncertain prognosis. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2018, 35, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antommaria, A.H.M.; Collura, C.A.; Antiel, R.M.; Lantos, J.D. Two infants, same prognosis, different parental preferences. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, A.A.; Davidson, J.E.; Morrison, W.; Danis, M.; White, D.B. Shared decision making in ICUs: An American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, H.S.; Wong, S.P.S.; Liu, F.Y.B.; Wong, H.L.; Fok, T.F.; Ng, P.C. Attitudes toward neonatal intensive care treatment of preterm infants with a high risk of developing long-term disabilities. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needle, J.S.; Mularski, R.A.; Nguyen, T.; Fromme, E.K. Influence of personal preferences for life-sustaining treatment on medical decision making among pediatric intensivists. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 2464–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.E.; Angus, D.C.; Weissfeld, L.A.; Puntillo, K.A.; Danis, M.; Deal, D.; Levy, M.M.; Cook, D.J. End-of-life care for the critically ill: A national intensive care unit survey. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 2547–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- October, T.W.; Jones, A.H.; Greenlick Michals, H.; Hebert, L.M.; Jiang, J.; Wang, J. Parental conflict, regret, and short-term impact on quality of life in tracheostomy decision-making. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 21, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, R.L.; Daly, B.J.; Lee, E. Decisional conflict and regret: Consequences of surrogate decision making for the chronically critically ill. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2012, 25, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukora, S.K.; Boss, R.D. Values-based shared decision-making in the antenatal period. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018, 23, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, A.P.; Carter, B.; Bray, L.; Donne, A.J. Parents’ experiences and views of caring for a child with a tracheostomy: A literature review. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 77, 1630–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Tang, C.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, L. A descriptive qualitative study of home care experiences in parents of children with tracheostomies. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 45, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.M.; Raisanen, J.C.; Shipman, K.J.; Jabre, N.A.; Wilfond, B.S.; Boss, R.D. Life with pediatric home ventilation: Expectations versus experience. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 3366–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, E.L.; Hutchins, J.V.; Thevasagayam, R. Quality of life in paediatric tracheostomy patients and their caregivers—A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 127, 109606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, J.; Bower, K.L.; Eskandanian, K. “100 things I wish someone would have told me”: Everyday challenges parents face while caring for their children with a tracheostomy. Qual. Health Res. 2024, 34, 1108–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boss, R.D.; Henderson, C.M.; Raisanen, J.C.; Jabre, N.A.; Shipman, K.; Wilfond, B.S. Family experiences deciding for and against pediatric home ventilation. J. Pediatr. 2021, 229, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nageswaran, S.; Gower, W.A.; Golden, S.L.; King, N.M.P. Collaborative decision-making: A framework for decision-making about life-sustaining treatments in children with medical complexity. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2022, 57, 3094–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Codesal, M.; Ofosu, D.B.; Mack, C.; Majaesic, C.; van Manen, M. Parents’ experiences of their children’s medical journeys with tracheostomies: A focus group study. Paediatr. Child Health 2024, 29, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, W.A.; Golden, S.L.; King, N.M.; Nageswaran, S. Decision making about tracheostomy for children with medical complexity: Caregiver and healthcare provider perspectives. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageswaran, S.; Banks, Q.; Golden, S.L.; Gower, W.A.; King, N.M.P. The role of religion and spirituality in caregiver decision-making about tracheostomy for children with medical complexity. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2022, 28, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabre, N.A.; Raisanen, J.C.; Shipman, K.J.; Henderson, C.M.; Boss, R.D.; Wilfond, B.S. Parent perspectives on facilitating decision-making around pediatric home ventilation. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2022, 57, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageswaran, S.; Gower, W.A.; King, N.M.P.; Golden, S.L. Tracheostomy decision-making for children with medical complexity: What supports and resources do caregivers need? Palliat. Support Care 2024, 22, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopelman, L.M. The best-interests standard as threshold, ideal, and standard of reasonableness. J. Med. Philos. 1997, 22, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, E.K.; Hester, D.M.; Vinarcsik, L.; Matheny Antommaria, A.H.; Bester, J.; Blustein, J.; Wright Clayton, E.; Diekema, D.S.; Iltis, A.S.; Kopelman, L.M.; et al. Pediatric decision making: Consensus recommendations. Pediatrics 2023, 152, e2023061832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, A.A.; Shepard, E.K.; Sederstrom, N.O.; Swoboda, S.M.; Marshall, M.F.; Birriel, B.; Rincon, F. Defining futile and potentially inappropriate interventions: A policy statement from the Society of Critical Care Medicine Ethics Committee. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 1769–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, J.F.; Tschirhart, M.D. Decision-Making Expertise. In The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance; Ericsson, K.A., Charness, N., Feltovich, P.J., Hoffman, R.R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum, J.P.W.; Barre, L.; Reed, C.; Passow, H. Participation of very old adults in health care decisions. Med. Decis. Mak. 2014, 34, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Kukora, S.K.; Arslanian-Engoren, C.; Deldin, P.J.; Pituch, K.; Yates, J.F. Aiding end-of-life medical decision-making: A Cardinal Issue Perspective. Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 18, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M.; Field, P.A. Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals, 2nd ed.; SAGE publications: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Krenz, C.; Spector-Bagdady, K.; De Vries, R.; Kukora, S.K. Parents’ perspectives on values and values conflicts impacting shared decision making for critically ill neonates. J. Pediatr. Ethics 2024, 3, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscigno, C.I.; Savage, T.A.; Kavanaugh, K.; Moro, T.T.; Kilpatrick, S.J.; Strassner, H.T.; Grobman, W.A.; Kimura, R.E. Divergent views of hope influencing communications between parents and hospital providers. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1232–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipstein, E.A.; Brinkman, W.B.; Britto, M.T. What is known about parents’ treatment decisions? A narrative review of pediatric decision making. Med. Decis. Mak. 2012, 32, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feudtner, C.; Walter, J.K.; Faerber, J.A.; Hill, D.L.; Carroll, K.W.; Mollen, C.J.; Miller, V.A.; Morrison, W.E.; Munson, D.; Kang, T.I.; et al. Good-parent beliefs of parents of seriously ill children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, A.; de Vries, M.; Berken, D.J.; van Dam, H.; Verweij, E.J.; Hogeveen, M.; Geurtzen, R. A scoping review of parental values during prenatal decisions about treatment options after extremely premature birth. Acta Paediatr. 2023, 112, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, E.C.; Burns, J.P.; Griffith, J.L.; Truog, R.D. Parental perspectives on end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 30, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- October, T.W.; Fisher, K.R.; Feudtner, C.; Hinds, P.S. The parent perspective: “Being a good parent” when making critical decisions in the PICU. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 15, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Martinez, E.; Noyes, J.; Bedolla, M. When to stop? Decision-making when children’s cancer treatment is no longer curative: A mixed-method systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, R.D.; Hutton, N.; Sulpar, L.J.; West, A.M.; Donohue, P.K. Values parents apply to decision-making regarding delivery room resuscitation for high-risk newborns. Pediatrics 2008, 122, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, A.; Sanson-Fisher, R.; Hall, A. Not having adequate time to make a treatment decision can impact on cancer patients’ care experience: Results of a cross-sectional study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1957–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, C.; Mailo, J.; Ofosu, D.; Hinai, A.A.; Keto-Lambert, D.; Soril, L.J.J.; van Manen, M.; Castro-Codesal, M. Tracheostomy and long-term invasive ventilation decision-making in children: A scoping review. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2024, 59, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feudtner, C. The breadth of hopes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 2306–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.R.; Feudtner, C. What else are you hoping for? Fostering hope in paediatric serious illness. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, 1004–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janvier, A.; Farlow, B.; Barrington, K.J. Parental hopes, interventions, and survival of neonates with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2016, 172, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, M.S. Life support decisions for children: What do parents value? Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1996, 19, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klee, K.; Wilfond, B.; Thomas, K.; Ridling, D. Conflicts between parents and clinicians: Tracheotomy decisions and clinical bioethics consultation. Nurs. Ethics 2022, 29, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfond, B.S. Tracheostomies and assisted ventilation in children with profound disabilities: Navigating family and professional values. Pediatrics 2014, 133 (Suppl. 1), S44–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, L.M.; Watson, A.C.; Madrigal, V.; October, T.W. Discussing benefits and risks of tracheostomy: What physicians actually say. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 18, e592–e597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boss, R.D.; Lemmon, M.E.; Arnold, R.M.; Donohue, P.K. Communicating prognosis with parents of critically ill infants: Direct observation of clinician behaviors. J. Perinatol. 2017, 37, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M.E.; Huffstetler, H.; Barks, M.C.; Kirby, C.; Katz, M.; Ubel, P.A.; Docherty, S.L.; Brandon, D. Neurologic outcome after prematurity: Perspectives of parents and clinicians. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20183819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aung, W.T.; Ong, N.Y.; Yeo, S.Q.C.; Juhari, N.S.B.; Kong, G.; Lim, N.A.; Amin, Z.; Ng, Y.P.M. Impact of pediatric tracheostomy on family caregivers’ burden and quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2025, 12, 1485544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinds, P.S.; Oakes, L.L.; Hicks, J.; Powell, B.; Srivastava, D.K.; Spunt, S.L.; Harper, J.; Baker, J.N.; West, N.K.; Furman, W.L. “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5979–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Value * |

|---|---|

| Children whose parents participated in interviews (n = 12) | |

| Age, median (range) | 6 months (2 months–14.6 years) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 8 (67) |

| Female | 4 (33) |

| Primary diagnostic categories, n (%) | |

| Genetic conditions | 5 (42) |

| Prematurity/Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 3 (25) |

| Brain injury/malformation | 3 (25) |

| Heart conditions | 1 (8) |

| Decision at the time of the interview, n (%) | |

| Tracheostomy | 10 (83) |

| 1. Tracheostomy already placed | 9 (90) |

| Time between tracheostomy placement and interview (range) | 1 day–approximately 3 months |

| 2. Before tracheostomy placement | 1 (10) |

| Time between interview and tracheostomy placement | 6 days |

| Pending/No tracheostomy | 2 (17) |

| Time between discussion and interview (range) | Ongoing/2–3 months |

| Parents who participated in interviews (n = 12) | |

| Age, median (range) | 31.5 yrs (19–63 yrs) |

| Relationship to the child, n (%) | |

| Biological mother | 11 (92) |

| Legal guardian (female) | 1 (8) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 9 (75) |

| Black or African American | 3 (25) |

| Religion, n (%) | |

| Christian/Catholic/Baptist | 9 (75) |

| None indicated | 1 (8) |

| Rather not say | 1 (8) |

| Missing | 1 (8) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 4 (33) |

| Unmarried (including other: 2 noted single, 1 noted engaged) | 8 (67) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Some or no high school | 3 (25) |

| High school | 1 (8) |

| Some college | 3 (25) |

| College graduate | 3 (25) |

| Master’s degree or higher | 2 (17) |

| Household income, n (%) | |

| <USD 30,000 | 2 (17) |

| USD 30,000–USD 50,000 | 1 (8) |

| USD 50,000–USD 90,000 | 4 (33) |

| >USD 90,000 | 1 (8) |

| Rather not say | 4 (33) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, H.; Arslanian-Engoren, C.; Pituch, K.J.; Deldin, P.J.; Graham-Bermann, S.A.; Kukora, S.K. Parental Values During Tracheostomy Decision-Making for Their Critically Ill Child: Interviews of Parents Who Just Made the Decision. Children 2025, 12, 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091115

Yan H, Arslanian-Engoren C, Pituch KJ, Deldin PJ, Graham-Bermann SA, Kukora SK. Parental Values During Tracheostomy Decision-Making for Their Critically Ill Child: Interviews of Parents Who Just Made the Decision. Children. 2025; 12(9):1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091115

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Haoyang, Cynthia Arslanian-Engoren, Kenneth J. Pituch, Patricia J. Deldin, Sandra A. Graham-Bermann, and Stephanie K. Kukora. 2025. "Parental Values During Tracheostomy Decision-Making for Their Critically Ill Child: Interviews of Parents Who Just Made the Decision" Children 12, no. 9: 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091115

APA StyleYan, H., Arslanian-Engoren, C., Pituch, K. J., Deldin, P. J., Graham-Bermann, S. A., & Kukora, S. K. (2025). Parental Values During Tracheostomy Decision-Making for Their Critically Ill Child: Interviews of Parents Who Just Made the Decision. Children, 12(9), 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091115