Parental Psychological Response to Prenatal Congenital Heart Defect Diagnosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background Data

1.2. Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Selection and Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Synthesis

2.7. Study Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

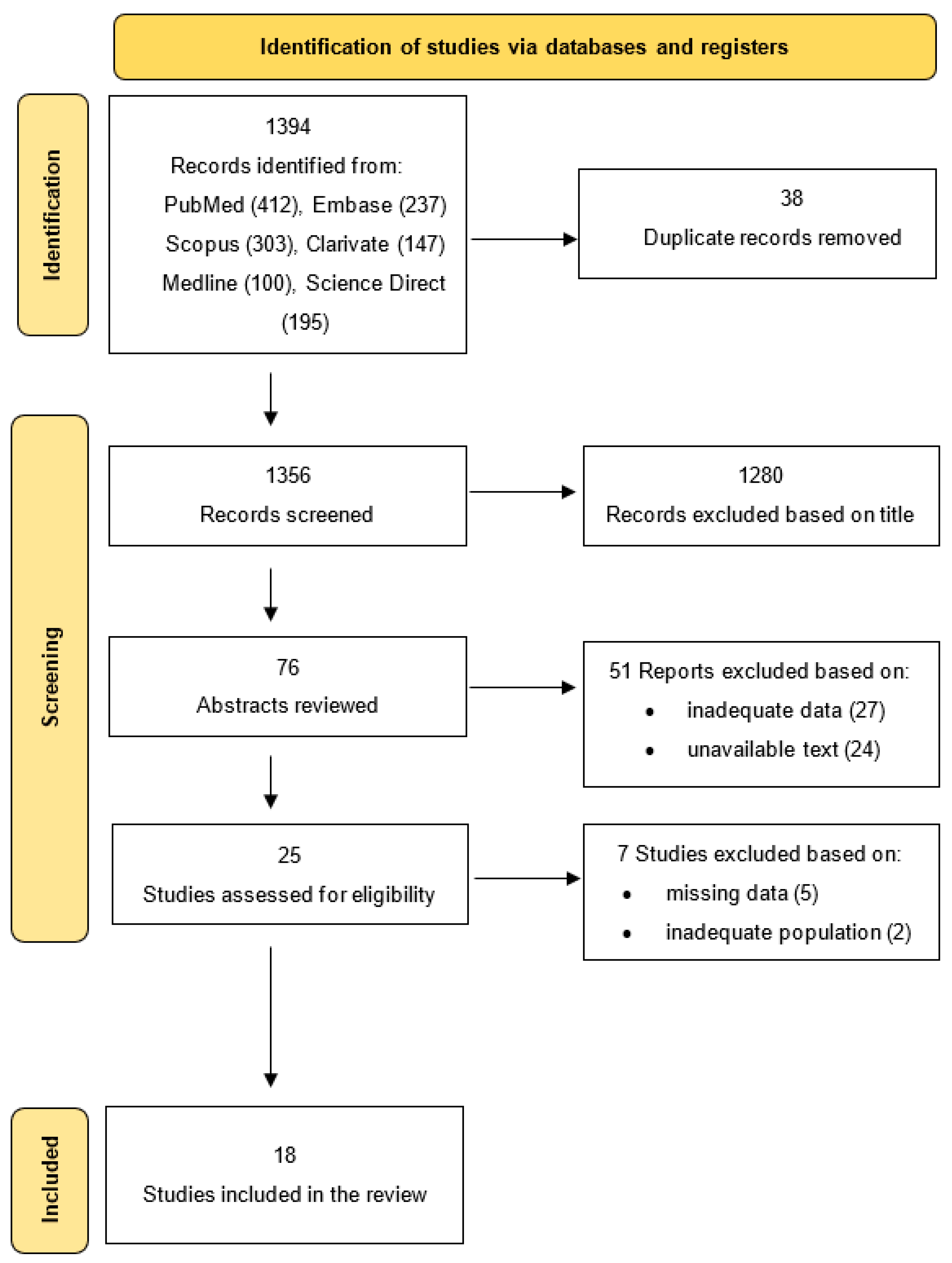

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Study Domain of Research and Outcomes

3.4. Predictors or Modifiers of Psychological Distress

3.5. Recommended Interventions for Reducing Psychological Distress

3.6. Study Quality and Risk of Bias

3.7. Heterogeneity and Publication Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. Anxiety

4.2. Depression

4.3. Stress

4.4. Post-Traumatic Stress

4.5. Coping Mechanisms

4.6. Attachment

4.7. Life Satisfaction and Mental Health/Wellbeing

4.8. Adaptative Processes

4.9. Limitations

4.10. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Donofrio, M.T.; Moon-Grady, A.J.; Hornberger, L.K.; Copel, J.A.; Sklansky, M.S.; Abuhamad, A.; Rychik, J. Diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014, 129, 2183–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linde, D.; Konings, E.E.; Slager, M.A.; Witsenburg, M.; Helbing, W.A.; Takkenberg, J.J.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, C.A.; Kirby, R.S.; Sever, L.E.; Langlois, P.H. Prevalence is the preferred measure of frequency of birth defects. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2005, 73, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, M.E.; Lee, K.A.; Honein, M.A.; Riehle-Colarusso, T.; Shin, M.; Correa, A. Temporal trends in survival among infants with critical congenital heart defects. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1502–e1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zych-Krekora, K.; Sylwestrzak, O.; Grzesiak, M.; Krekora, M. Impact of Prenatal and Postnatal Diagnosis on Parents: Psychosocial and Economic Aspects Related to Congenital Heart Defects in Children. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mutti, G.; Ait Ali, L.; Marotta, M.; Nunno, S.; Consigli, V.; Baratta, S.; Orsi, M.L.; Mastorci, F.; Vecoli, C.; Pingitore, A.; et al. Psychological Impact of a Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease on Parents: Is. It Time for Tailored Psychological Support? J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Connor, T.G.; Heron, J.; Golding, J.; Beveridge, M.; Glover, V. Maternal antenatal anxiety and children’s behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. Report from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, K.J.; Glover, V.; Barker, E.D.; O’Connor, T.G. The persisting effect of maternal mood in pregnancy on childhood psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winsper, C.; Wolke, D.; Lereya, T. Prospective associations between prenatal adversities and borderline personality disorder at 11–12 years. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinney, D.K.; Miller, A.M.; Crowley, D.J.; Huang, E.; Gerber, E. Autism prevalence following prenatal exposure to hurricanes and tropical storms in Louisiana. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.L.; Moore, C.F.; Kraemer, G.W.; Roberts, A.D.; DeJesus, O.T. The impact of prenatal stress, fetal alcohol exposure, or both on development: Perspectives from a primate model. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2002, 27, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramchandani, P.G.; Stein, A.; O’Connor, T.G.; Heron, J.; Murray, L.; Evans, J. Depression in men in the postnatal period and later child psychopathology: A population cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dandy, S.; Wittkowski, A.; Murray, C.D. Parents’ experiences of receiving their child’s diagnosis of congenital heart disease: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2024, 29, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekkhus, M.; Oftedal, A.; Braithwaite, E.; Haugen, G.; Kaasen, A. Paternal Psychological Stress After Detection of Fetal Anomaly During Pregnancy. A Prospective Longitudinal Observational Study. Front Psychol. 2020, 11, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Asplin, N.; Wessel, H.; Marions, L.; Georgsson Öhman, S. Maternal emotional wellbeing over time and attachment to the fetus when a malformation is detected. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2015, 6, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, F.; Morini, F.; Ragni, B.; Braguglia, A.; Gentile, S.; Zaccara, A.; Bagolan, P.; Aite, L. Pediatric medical traumatic stress (PMTS) in parents of newborns with a congenital anomaly requiring surgery at birth. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 56, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf-King, S.E.; Anger, A.; Arnold, E.A.; Weiss, S.J.; Teitel, D. Mental Health Among Parents of Children With Critical Congenital Heart Defects: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnson, J.; Dunning, A.; Sattar, R.; Arezina, J.; Karkowsky, E.C.; Thomas, S.; Panagioti, M. Delivering unexpected news via obstetric ultrasound: A systematic review and meta-ethnographic synthesis of expectant parent and staff experiences. Sonography 2020, 7, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Nazaré, B.; Canavarro, M.C. Parental psychological distress and quality of life after a prenatal or postnatal diagnosis of congenital anomaly: A controlled comparison study with parents of healthy infants. Disabil. Health J. 2012, 5, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, F.; Palatta, S.; Mirante, N.; Cuttini, M.; Seganti, G.; Dotta, A.; Piersigilli, F. Birth of a child with congenital heart disease: Emotional reactions of mothers and fathers according to time of diagnosis. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013, 26, 1249–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, M.R.B.; Prouhet, P.M.; Russell, C.L.; Pfannenstiel, B.R. Quality of Life for Parents of Children With Congenital Heart Defect: A Systematic Review. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2018, 33, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, T.; Bergman, G.; Melander Marttala, U.; Wadensten, B.; Mattsson, E. Information following a diagnosis of congenital heart defect: Experiences among parents to prenatally diagnosed children. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carlsson, T.; Bergman, G.; Wadensten, B.; Mattsson, E. Experiences of informational needs and received information following a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defect. Prenat. Diagn. 2016, 36, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoehn, K.S.; Wernovsky, G.; Rychik, J.; Tian, Z.Y.; Donaghue, D.; Alderfer, M.A.; Gaynor, J.W.; Kazak, A.E.; Spray, T.L.; Nelson, R.M. Parental decision-making in congenital heart disease. Cardiol. Young 2004, 14, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rychik, J.; Donaghue, D.D.; Levy, S.; Fajardo, C.; Combs, J.; Zhang, X.; Szwast, A.; Diamond, G.S. Maternal psychological stress after prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease. J. Pediatr. 2013, 162, 302–307.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vieira, D.R.; Ruschel, P.P.; Schmidt, M.M.; Zielinsky, P. Prenatal diagnosis of critical congenital heart disease associated with lower postpartum depressive symptoms: A case-control study. J. Pediatr. (Rio. J.) 2025, 101, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McKechnie, A.C.; Elgersma, K.M.; Iwaszko Wagner, T.; Trebilcock, A.; Damico, J.; Sosa, A.; Ambrose, M.B.; Shah, K.; Sanchez Mejia, A.A.; Pridham, K.F. An mHealth, patient engagement approach to understand and address parents’ mental health and caregiving needs after prenatal diagnosis of critical congenital heart disease. PEC Innov. 2023, 3, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Erbas, G.S.; Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Ostermayer, E.; Kovacevic, A.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Ewert, P.; Wacker-Gussmann, A. Anxiety and Depression Levels in Parents after Counselling for Fetal Heart Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mangin-Heimos, K.S.; Strube, M.; Taylor, K.; Galbraith, K.; O’Brien, E.; Rogers, C.; Lee, C.K.; Ortinau, C. Trajectories of Maternal and Paternal Psychological Distress After Fetal Diagnosis of Moderate-Severe Congenital Heart Disease. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2023, 48, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Demianczyk, A.C.; Bechtel Driscoll, C.F.; Karpyn, A.; Shillingford, A.; Kazak, A.E.; Sood, E. Coping strategies used by mothers and fathers following diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Child. Care Health Dev. 2022, 48, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, Y.; Kapse, K.; Jacobs, M.; Niforatos-Andescavage, N.; Donofrio, M.T.; Krishnan, A.; Vezina, G.; Wessel, D.; du Plessis, A.; Limperopoulos, C. Association of Maternal Psychological Distress with in Utero Brain Development in Fetuses with Congenital Heart Disease. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, e195316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harris, K.W.; Brelsford, K.M.; Kavanaugh-McHugh, A.; Clayton, E.W. Uncertainty of Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease: A Qualitative Study. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e204082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bratt, E.L.; Järvholm, S.; Ekman-Joelsson, B.M.; Johannsmeyer, A.; Carlsson, S.Å.; Mattsson, L.Å.; Mellander, M. Parental reactions, distress, and sense of coherence after prenatal versus postnatal diagnosis of complex congenital heart disease. Cardiol. Young 2019, 29, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, Y.M.; Yun, T.J.; Yoo, I.Y.; Kim, S.; Jin, J.; Kim, S. The pregnancy experience of Korean mothers with a prenatal fetal diagnosis of congenital heart disease. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pinto, N.M.; Weng, C.; Sheng, X.; Simon, K.; Byrne, J.B.; Miller, T.; Puchalski, M.D. Modifiers of stress related to timing of diagnosis in parents of children with complex congenital heart disease. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 29, 3340–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratt, E.L.; Järvholm, S.; Ekman-Joelsson, B.M.; Mattson, L.Å.; Mellander, M. Parent’s experiences of counselling and their need for support following a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease—A qualitative study in a Swedish context. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ruschel, P.; Zielinsky, P.; Grings, C.; Pimentel, J.; Azevedo, L.; Paniagua, R.; Nicoloso, L.H. Maternal-fetal attachment and prenatal diagnosis of heart disease. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 174, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosig, C.L.; Whitstone, B.N.; Frommelt, M.A.; Frisbee, S.J.; Leuthner, S.R. Psychological distress in parents of children with severe congenital heart disease: The impact of prenatal versus postnatal diagnosis. J. Perinatol. 2007, 27, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklansky, M.; Tang, A.; Levy, D.; Grossfeld, P.; Kashani, I.; Shaughnessy, R.; Rothman, A. Maternal psychological impact of fetal echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2002, 15, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranley, M.S. Development of a tool for the measurement of maternal attachment during pregnancy. Nurs. Res. 1981, 30, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y); Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanier, G.B. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J. Marriage Fam. 1976, 38, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.P.; Williams, P. A User’s Guide to the General Health Questionnaire; NFER-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, D.S.; Marmar, C.R. The Impact of Event Scale—Revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD; Wilson, J.P., Keane, T.M., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual; National Computer Systems: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fenster, L.; Schaefer, C.; Mathur, A.; Hiatt, R.A.; Pieper, C.; Hubbard, A.E.; Swan, S.H. Psychologic Stress in the Workplace and Spontaneous Abortion. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1995, 142, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurki, T.; Hiilesmaa, V.; Raitasalo, R.; Mattila, H.; Ylikorkala, O. Depression and anxiety in early pregnancy and risk for preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 95, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bergh, B.R.; Mulder, E.J.; Mennes, M.; Glover, V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruceanu, C.; Matosin, N.; Binder, E.B. Interactions of early-life stress with the genome and epigenome: From prenatal stress to psychiatric disorders. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 14, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accortt, E.E.; Wong, M.S. It Is Time for Routine Screening for Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Obstetrics and Gynecology Settings. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2017, 72, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton-Kamm, D.; Sklansky, M.; Chang, R.K. How Not to Tell Parents About Their Child’s New Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease: An Internet Survey of 841 Parents. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2014, 35, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, O.; Burch, M.; Manning, N.; Sleeman, K.; Gould, S.; Archer, N. Prenatal diagnosis of coarctation of the aorta improves survival and reduces morbidity. Heart 2002, 87, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunfeld, J.A.; Tempels, A.; Passchier, J.; Hazebroek, F.W.; Tibboel, D. Brief report: Parental cburden and grief one year after the birth of a child with a congenital anomaly. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 1999, 24, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, M.; Khadivzadeh, T.; Nekah, S.M.A.; Ebrahimipour, H. Informational needs of pregnant women following the prenatal diagnosis of fetal anomalies: A qualitative study in Iran. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, F.A.; Stewart, M.; McCusker, C.G.; Morrison, M.L.; Molloy, B.; Doherty, N.; Craig, B.G.; Sands, A.J.; Rooney, N.; Mulholland, H.C. Examination of the physical and psychosocial determinants of health behaviour in 4–5-year-old children with congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol. Young 2010, 20, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCusker, C.G.; Doherty, N.N.; Molloy, B.; Casey, F.; Rooney, N.; Mulholland, C.; Sands, A.; Craig, B.; Stewart, M. Determinants of neuropsychological and behavioural outcomes in early childhood survivors of congenital heart disease. Arch. Dis. Child. 2007, 92, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ernst, M.M.; Marino, B.S.; Cassedy, A.; Piazza-Waggoner, C.; Franklin, R.C.; Brown, K.; Wray, J. Biopsychosocial Predictors of Quality of Life Outcomes in Pediatric Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2018, 39, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asplin, N.; Wessel, H.; Marions, L.; Georgsson Öhman, S. Pregnant women’s experiences, needs, and preferences regarding information about malformations detected by ultrasound scan. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2012, 3, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKechnie, R.; MacLeod, R.; Keeling, S. Facing uncertainty: The lived experience of palliative care. Palliat. Support. Care 2007, 5, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCusker, C.G.; Armstrong, M.P.; Mullen, M.; Doherty, N.N.; Casey, F.A. A sibling-controlled, prospective study of outcomes at home and school in children with severe congenital heart disease. Cardiol. Young 2013, 23, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, L.; Carter, B.; Sanders, C.; Blake, L.; Keegan, K. Parent-to-parent peer support for parents of children with a disability: A mixed method study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1537–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumsden, M.R.; Smith, D.M.; Wittkowski, A. Coping in parents of children with congenital heart disease: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 1736–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilling, V.; Morris, C.; Thompson-Coon, J.; Ukoumunne, O.; Rogers, M.; Logan, S. Peer support for parents of children with chronic disabling conditions: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2013, 55, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Publication Year | Study Design Ant Type | Location | Number of Parents Expecting Children with CHD Included, Controls, Age | Type of Tools Used for Evaluation (Questionnaires, Interviews, Scales) | Follow-Up Period | Specific Domain of Research Related to Parental Psychological Issues | Main Outcomes | Predictors or Modifiers of Psychological Distress | Recommended Interventions for Reduction in Psychological Distress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vieira, 2025 [27] | Case–control study; quantitative | Porto Alegre, Brazil | 50 puerperal women: 23 mothers with prenatal CHD diagnosis of the fetus age 32.6 ± 5.3 and 27 controls (mothers with postnatal CHD diagnosis of their child) age 27.2 ± 5.9 years | Semi-structured questionnaire, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale | - | Depressive symptoms | Prenatal diagnosis of CHD was associated with significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms (26.1% at prenatally vs. 77.8% at postnatally diagnosis) | Time of diagnosis | Fetal diagnosis should be offered to all mothers |

| McKechnie, 2023 [28] | Prospective study; qualitative | Minneapolis, Houston, and Madison, USA | 19 mothers/birthing persons and 15 caregiving partners, age 33.5 (32–36.5) years | Online surveys, session transcripts, and app use | 12 weeks postnatally | Mental health/wellbeing | Regulating emotions and co-parenting consistently needed support | Use nurse–parent collaborative in preparing heart and mind topics | |

| Erbas, 2023 [29] | Longitudinal study; quantitative | Munich, Germany | 77 parents (45 women and 32 men), no controls, 33.7± 5.262 years | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale questionnaire | 5–13 months after the birth of the child | Psychological state (anxiety and depression) | Prevalence for prenatal anxiety was 11.8% and for depressed mood 6.6% | Level of education, health and social workers, first-time mothers and parents whose pregnancies were due to medical assistance | The support of the affected parents can positively impact the treatment of the child and should be integrated into the daily routine of the clinic |

| Mangin-Heimos, 2022 [30] | Prospective longitudinal study; quantitative | St. Louis, USA | 43 mothers, 28.2 (23.4–33.0) years, and 36 partners, 30.6 (25.7–33.3) years, no controls | Depression Anxiety Stress Scales | Prenatal, birth, discharge, post-discharge | Psychological distress | Psychological distress was present in 42% (18/43) of mothers and 22% (8/36) of fathers | Low social support for mothers and a history of mental health conditions for fathers | These data suggest that early and repeated psychological screening is important once a fetal CHD diagnosis is made and that providing mental health and social support to parents may be an important component of their ongoing care |

| Demianczyk, 2022 [31] | Cross-sectional study; qualitative | Philadelphia and Delaware, USA | 34 parents (20 mothers and 14 fathers), no controls | Semi-structured interviews—COPE Inventory | 1–3 years postnatally | Coping strategies (adaptive and maladaptive strategies) | Mothers were more likely than fathers to report a focus on and venting of emotions (70% vs. 21.43%) and behavioral disengagement (25% vs. 0%) | Time of diagnosis | Interventions tailored to the needs of mothers and fathers for coping strategies are needed to promote adaptive coping and optimize family psychosocial outcomes |

| Wu, 2020 [32] | Longitudinal, prospective, case–control study; quantitative | Washington, USA | 48 pregnant women carrying fetuses with CHD age 32.7 ± 5.5 years and 92 healthy volunteers with low-risk pregnancies, age 33.7 ± 5.4 years | Perceived Stress Scale, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale | - | Maternal psychological distress, anxiety, and depression | 65% of mothers tested positive for stress, 44% for anxiety, and 29% for depression | Fetuses with single-ventricle CHD | Psychological distress among women carrying fetuses with CHDs is prevalent and is associated with impaired fetal cerebellar and hippocampal development; efforts should be made to decrees this distress |

| Harris, 2020 [33] | Quantitative | Nashville, USA | 16 mothers, age 30.0 [27.3–34.8] years), 8 fathers, and 3 support individuals age of family member or support individual, 30.0 [26.0–42.0] years), no controls | Audio recorded telephone interviews | 1 prenatal follow-up visit and 1 postnatal follow-up visit | Prenatal experience, particularly aspects they found to be stressful or challenging | Uncertainty was identified as a pervasive central theme and was related both to concrete questions on scheduling, logistics, or next steps, and long-term unknown variables concerning the definitiveness of the diagnosis or overall prognosis | Potential future interventions to improve parental support were identified in the areas of expectation setting before the referral visit, communication in clinic, and identity formation after the new diagnosis | |

| Bratt, 2019 [34] | Prospective study; quantitative | Gothenburg, Boras and Trollhattan, Sweden | 8 couples age 31.5± 4.1 years and 152 controls age 30.8 ± 4.7 years (pregnant women with a normal screening ultrasound examination) | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, sense of coherence, life satisfaction, and Dyadic Adjustment Scale | 2–6 months after delivery | levels of parental distress | The prenatal diagnosis of CHD led to lower sense of coherence, higher levels of anxiety and lower life satisfaction | Time of diagnosis | Parents with a prenatal diagnosis of CHD should be supported through the pregnancy |

| Im, 2018 [35] | Cross-sectional study; qualitative | Seoul, Republic of Korea | 12 mothers, median age 31.5 years, no controls | In-depth interview | 1–6 months | Adaptive processes during pregnancy | Mothers went through a dynamic process of adapting to the unexpected diagnosis of CHD, which was closely linked to being able to believe that their child could be treated | Provision of accurate health advice and emotional support by a multidisciplinary counseling team | Early counseling with precise information on CHD, continuous provision of clear explanations on prognosis, sufficient emotional support, and well-designed prenatal education programs are the keys to an optimal outcome |

| Carlsson, 2016 [23] | Quantitative | Stockholm and Uppsala, Sweden | 26 parents of a fetus with CHD (14 mothers, 12 fathers) | Semi-structured telephone interviews | - | Need for information | Individuals faced with a prenatal diagnosis of a congenital heart defect need individualized and repeated information | Information regarding pregnancy termination is needed | |

| Pinto, 2016 [36] | Prospective cohort study; quantitative | Salt Lake City, USA | 60 families with prenatal CHD diagnosis, 45 families with postnatal CHD diagnosis, average age of parents (mothers 28.2 versus 27.6 years, fathers 29.9 versus 29.2 years) | Basic Symptom Inventory | At birth, and follow-up | Psychological stress | Parents of prenatally diagnosed infants with CHD had lower anxiety and stress than those diagnosed postnatally after adjusting for severity; scores for anxiety and stress were primarily lower in fathers | Timing of diagnosis | Fetal diagnosis should be offered to all mothers |

| Carlsson, 2015 [22] | Qualitative | Stockholm and Uppsala, Sweden | 11 parents of a fetus with CHD (6 fathers and 5 mothers) | Semi-structured interviews | - | Parental experiences and need for information following a prenatal diagnosis of CHD | Three different themes emerged: “Grasping the facts today while reflecting on the future”, “Personal contact with medical specialists who give honest and trustworthy information is valued”, and “An overwhelming amount of information on the Internet” | Early and honest information in line with individual preferences is crucial to support the decisional process regarding whether to continue or terminate the pregnancy; the use of illustrations is recommended, as a complement to oral information, as it increases comprehension and satisfaction with obtained information | |

| Bratt, 2015 [37] | Qualitative | Gothenburg, Sweden | 6 couples, age 33 (24–37) years | Interviews performed 5–9 weeks after a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease | - | Experiences of counselling and need for support during continued pregnancy following a prenatal diagnosis of a CHD | The analysis resulted in three themes: 1/Counselling and making a decision-the importance of knowledge and understanding; 2/Continued support during pregnancy; 3/Next step—the near future | Web-based information of high-quality, written information, support from parents with similar experiences and continued contact with a specialist liaison nurse | Continued support throughout pregnancy was considered important |

| Bevilacqua, 2013 [20] | Cross-sectional; quantitative | Rome, Italy | 38 couples, 20 with prenatal diagnosis of CHD (mothers age 33.7 ± 5.9 years, fathers age 36.1 ± 6.5 years) and 18 with postnatal diagnosis of CHD (mothers age 32.8 ± 5.2 years, fathers age 36.8 ± 7.1 years) | Three self-administered questionnaires (General Health Questionnaire-30, Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition, Health Survey-36) | - | Emotional distress, depression, and quality of life | Stress and depression levels were significantly higher in mothers than in fathers (stress: 81.8% mothers versus 60.6% fathers; depression: 45.7% mothers versus 20.0% fathers); mothers receiving prenatal diagnosis were more depressed, whereas those receiving postnatal diagnosis were more stressed; fathers showed same tendency | Sex of the parent | Parents of children diagnosed prenatally may need counseling throughout pregnancy to help them recover from the loss of the imagined healthy child |

| Ruschel, 2013 [38] | Cohort study; quantitative | Porto Alegre, Brazil | 197 pregnant women were included, 96 with a fetus with CHD age 28.97 6.89 years and 101 with a fetus without CHD age 27.61 6.40 years | Validated Maternal–Fetal Attachment Scale | After 30 days | Maternal–fetal attachment | Diagnosis of fetal heart disease increases the level of maternal–fetal attachment | Time of diagnosis | Fetal diagnosis should be offered to all mothers |

| Rychik, 2012 [25] | Cross-sectional survey; quantitative | Philadelphia, USA | 59 mothers having a fetus with CHD, age 30± 7 years | Self-report instruments (Impact of Events Scale-Revised, Beck Depression Index II, State-Trait Anxiety Index, COPE Inventory, Dyadic Adjustment Scale) | - | Maternal stress traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety | Post-traumatic stress (39%), depression (22%), and anxiety (31%) are common after prenatal diagnosis of CHD; lower partner satisfaction was associated with higher depression and higher anxiety | Coping skills, partner satisfaction and demographics | Healthy partner relationships and positive coping mechanisms can act as buffers |

| Brosig, 2007 [39] | Cross-sectional; quantitative | Wisconsin, USA | 10 couples with prenatal CHD diagnosis and 16 couples with postnatal CHD diagnosis | Brief Symptom Inventory, Interview | Psychological distress | The severity of the child’s heart lesion at diagnosis was related to parental distress levels; parents with children with more severe lesions had higher BSI scores | Severity of the child’s heart lesion | Results suggest the need to provide parents with psychological support, regardless of the timing of diagnosis | |

| Sklansky, 2002 [40] | Prospective study; quantitative | San Diego, USA | 29 mothers with prenatal CHD diagnosis, 184 mothers with normal fetal echocardiography, 28 mothers with neonatal CHD diagnosis | Questionnaire | After birth in the neonatal period | Maternal psychological impact | When fetal CHD was diagnosed, maternal anxiety typically increased, and mothers commonly felt less happy about being pregnant, less responsible for their infants’ defects and tended to have improved their relationships with the infants’ fathers | Time of diagnosis | Fetal diagnosis should be offered to all mothers; it is a tool with great psychological and medical impact |

| Study | Confounding | Selection | Classification | Deviations | Missing Data | Measurement | Reporting | Overall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vieira [27] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Erbas [29] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Mangin-Heimos [30] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Wu [32] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Bratt [34] | High | High | Low | Low | High | High | Moderate | High |

| Pinto [36] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Bevilacqua [20] | High | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Ruschel [38] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Rychik [25] | High | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Brosig [39] | High | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Sklansky [40] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Study | CASP Score (/10) | Quality Level |

|---|---|---|

| McKechnie [28] | 7 | Moderate |

| Demianczyk [31] | 6 | Moderate |

| Harris [33] | 5 | Low–Moderate |

| Im [35] | 6 | Moderate |

| Carlsson [23] | 7 | Moderate |

| Carlsson [22] | 6 | Moderate |

| Bratt [37] | 5 | Low–Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tecar, C.; Chiperi, L.E.; Muresanu, D.F. Parental Psychological Response to Prenatal Congenital Heart Defect Diagnosis. Children 2025, 12, 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081095

Tecar C, Chiperi LE, Muresanu DF. Parental Psychological Response to Prenatal Congenital Heart Defect Diagnosis. Children. 2025; 12(8):1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081095

Chicago/Turabian StyleTecar, Cristina, Lacramioara Eliza Chiperi, and Dafin Fior Muresanu. 2025. "Parental Psychological Response to Prenatal Congenital Heart Defect Diagnosis" Children 12, no. 8: 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081095

APA StyleTecar, C., Chiperi, L. E., & Muresanu, D. F. (2025). Parental Psychological Response to Prenatal Congenital Heart Defect Diagnosis. Children, 12(8), 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081095