Sex Differences in Wheezing During the First Three Years of Life After Delivery via Caesarean Section

Abstract

Highlights

- Girls delivered by caesarean section had a higher likelihood of developing preschool wheezing compared to those born vaginally.

- Wheezing within the first three years of life was more common in boys born by caesarean section compared to girls.

- Our findings could assist in counselling of families in relation to the likelihood of future wheezing according to method of delivery.

- Our results highlight altered microbial colonisation as a potential mechanism for the development of wheezing in early childhood following birth with caesarean section.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

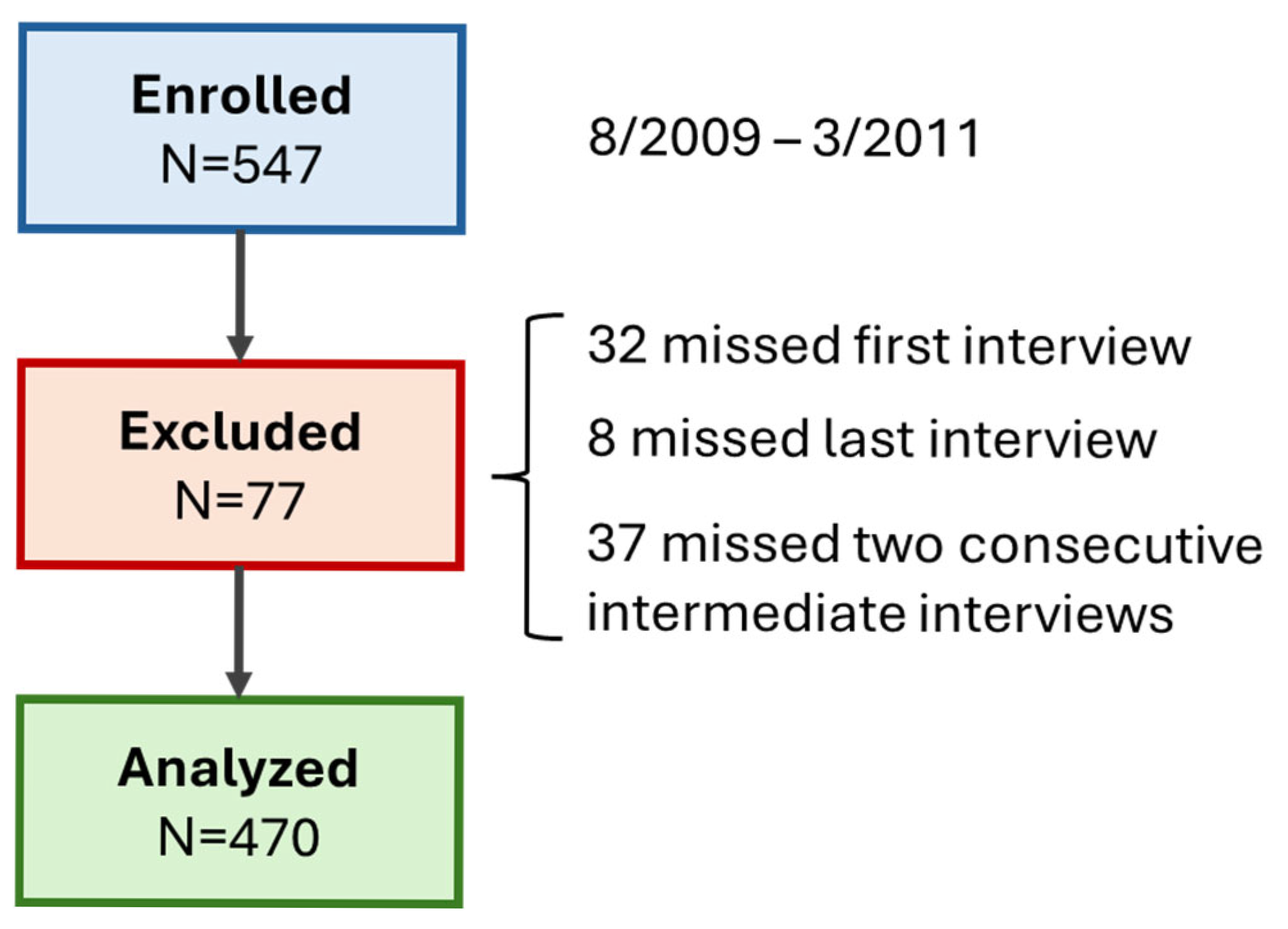

2.1. Type, Duration, and Location of the Study

2.2. Study Population and Design

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stokholm, J.; Thorsen, J.; Chawes, B.L.; Schjorring, S.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Bonnelykke, K.; Bisgaard, H. Cesarean Section Changes Neonatal Gut Colonization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorksten, B.; Sepp, E.; Julge, K.; Voor, T.; Mikelsaar, M. Allergy Development and the Intestinal Microflora during the First Year of Life. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001, 108, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Fang, F.; Bao, Y. Is Elective Cesarean Section Associated with a Higher Risk of Asthma? A Meta-Analysis. J. Asthma 2015, 52, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thavagnanam, S.; Fleming, J.; Bromley, A.; Shields, M.D.; Cardwell, C.R. A Meta-Analysis of the Association between Caesarean Section and Childhood Asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2008, 38, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuseini, H.; Newcomb, D.C. Mechanisms Driving Gender Differences in Asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz-Polster, H.; David, M.R.; Buist, A.S.; Vollmer, W.M.; O’Connor, E.A.; Frazier, E.A.; Wall, M.A. Caesarean Section Delivery and the Risk of Allergic Disorders in Childhood. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2005, 35, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnus, M.C.; Haberg, S.E.; Stigum, H.; Nafstad, P.; London, S.J.; Vangen, S.; Nystad, W. Delivery by Cesarean Section and Early Childhood Respiratory Symptoms and Disorders: The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wladimiroff, J.; Tsiapakidou, S.; Mahmood, T.; Velebil, P. Caesarean Section Rates across Europe and Its Impact on Specialist Training in Obstetrics: A Qualitative Review by the Standing Committee of Hospital Visiting Programme for Training Recognition of the European Board and College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (EBCOG). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 304, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papathoma, E.; Triga, M.; Fouzas, S.; Dimitriou, G. Cesarean Section Delivery and Development of Food Allergy and Atopic Dermatitis in Early Childhood. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 27, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosson, E. Diagnostic Criteria for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2010, 36, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammaro, A.; Carrara, S.; Cavaliere, A.; Ermito, S.; Dinatale, A.; Pappalardo, E.M.; Militello, M.; Pedata, R. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. J. Prenat. Med. 2009, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, T.J.; Williams, A.F.; Wright, C.M.; Group, R.G.C.E. Revised Birth Centiles for Weight, Length and Head Circumference in the UK-WHO Growth Charts. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2011, 38, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Lawama, M.; AlZaatreh, A.; Elrajabi, R.; Abdelhamid, S.; Badran, E. Prolonged Rupture of Membranes, Neonatal Outcomes and Management Guidelines. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2019, 11, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallol, J.; Garcia-Marcos, L.; Sole, D.; Brand, P.; EISL Study Group. International Prevalence of Recurrent Wheezing during the First Year of Life: Variability, Treatment Patterns and Use of Health Resources. Thorax 2010, 65, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patria, M.F.; Esposito, S. Recurrent Lower Respiratory Tract Infections in Children: A Practical Approach to Diagnosis. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2013, 14, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, H.C.; Burney, P.G.; Hay, R.J.; Archer, C.B.; Shipley, M.J.; Hunter, J.J.; Bingham, E.; Finlay, A.; Pembroke, A.; Cgraham-Brown, R.; et al. The U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis. I. Derivation of a Minimum Set of Discriminators for Atopic Dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 1994, 131, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, A.; Ramlau-Hansen, C.H.; Jeppesen, S.K.; Thulstrup, A.M.; Olsen, J. Caesarean Delivery and Risk of Developing Asthma in the Offspring. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 96, 595–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, A.F.; Strickland, M.J.; Klein, M.; Drews-Botsch, C.; Hansen, C.; Darrow, L.A. Caesarean Delivery, Childhood Asthma, and Effect Modification by Sex: An Observational Study and Meta-Analysis. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2018, 32, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almqvist, C.; Worm, M.; Leynaert, B.; Working Group of GALENWPG. Impact of Gender on Asthma in Childhood and Adolescence: A GA2LEN Review. Allergy 2008, 63, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandhane, P.J.; Greene, J.M.; Cowan, J.O.; Taylor, D.R.; Sears, M.R. Sex Differences in Factors Associated with Childhood- and Adolescent-Onset Wheeze. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 172, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthracopoulos, M.B.; Pandiora, A.; Fouzas, S.; Panagiotopoulou, E.; Liolios, E.; Priftis, K.N. Sex-Specific Trends in Prevalence of Childhood Asthma over 30 Years in Patras, Greece. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrinioti, H.; Fainardi, V.; Bonnelykke, K.; Custovic, A.; Cicutto, L.; Coleman, C.; Eiwegger, T.; Kuehni, C.; Moeller, A.; Pedersen, E.; et al. European Respiratory Society Statement on Preschool Wheezing Disorders: Updated Definitions, Knowledge Gaps and Proposed Future Research Directions. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, 2400624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penders, J.; Stobberingh, E.E.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Thijs, C. The Role of the Intestinal Microbiota in the Development of Atopic Disorders. Allergy 2007, 62, 1223–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjögren, Y.M.; Jenmalm, M.C.; Böttcher, M.F.; Björkstén, B.; Sverremark-Ekström, E. Altered Early Infant Gut Microbiota in Children Developing Allergy up to 5 Years of Age. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2009, 39, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, H.; Hird, S.M.; Chen, M.H.; Xu, W.; Maas, K.; Cong, X. Sex Differences in Gut Microbial Development of Preterm Infant Twins in Early Life: A Longitudinal Analysis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 671074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, K.M.; Plagemann, A.; Sommer, J.; Hofmann, M.; Henrich, W.; Surette, M.G.; Braun, T.; Sloboda, D.M. Delivery Mode, Birth Order, and Sex Impact Neonatal Microbial Colonization. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2491667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.C.; Wood, A.M.; White, I.R.; Pell, J.P.; Cameron, A.D.; Dobbie, R. Neonatal Respiratory Morbidity at Term and the Risk of Childhood Asthma. Arch. Dis. Child. 2004, 89, 956–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres-de-Campos, D.; Simon, A.; Modi, N.; Tudose, M.; Saliba, E.; Wielgos, M.; Reyns, M.; Athanasiadis, A.; Stenback, P.; Verlohren, S.; et al. European Association of Perinatal Medicine (EAPM) European Midwives Association (EMA) Joint Position Statement: Caesarean Delivery Rates at a Country Level Should Be in the 15–20% Range. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 294, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prenatal | Maternal age (years) | 31 (27–34) |

| Maternal atopy | 66 (14) | |

| Paternal atopy | 55 (12) | |

| Pregnancy | Gestational diabetes mellitus | 57 (12) |

| Hypertensive disease of pregnancy | 12 (3) | |

| Maternal smoking | 143 (30) | |

| Delivery | Male sex | 250 (53) |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.5 (37.4–39.6) | |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.20 (2.86–3.50) | |

| Birth weight z-score | −0.01 (−0.62–0.64) | |

| Caesarean section | 240 (51) | |

| Elective caesarean section | 205 (44) | |

| Meconium-stained amniotic fluid | 34 (7) | |

| Prolonged rupture of membranes | 18 (4) | |

| Apgar score at 10 min | 9 (8–10) | |

| Neonatal | Admission to neonatal care | 28 (6) |

| Breastfeeding | 158 (34) | |

| Follow up | Wheezing | 144 (31) |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 98 (21) | |

| Beta 2 agonists | 259 (55) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papathoma, E.; Dassios, T.; Triga, M.; Fouzas, S.; Dimitriou, G. Sex Differences in Wheezing During the First Three Years of Life After Delivery via Caesarean Section. Children 2025, 12, 1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081071

Papathoma E, Dassios T, Triga M, Fouzas S, Dimitriou G. Sex Differences in Wheezing During the First Three Years of Life After Delivery via Caesarean Section. Children. 2025; 12(8):1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081071

Chicago/Turabian StylePapathoma, Evangelia, Theodore Dassios, Maria Triga, Sotirios Fouzas, and Gabriel Dimitriou. 2025. "Sex Differences in Wheezing During the First Three Years of Life After Delivery via Caesarean Section" Children 12, no. 8: 1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081071

APA StylePapathoma, E., Dassios, T., Triga, M., Fouzas, S., & Dimitriou, G. (2025). Sex Differences in Wheezing During the First Three Years of Life After Delivery via Caesarean Section. Children, 12(8), 1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081071