Relationship Between Personality of Parents and Pediatric Post-Intensive Care Syndrome for a Family in the PICU: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Patient Selection

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Participants

3.2. Parent Characteristics

3.3. Patient Characteristics

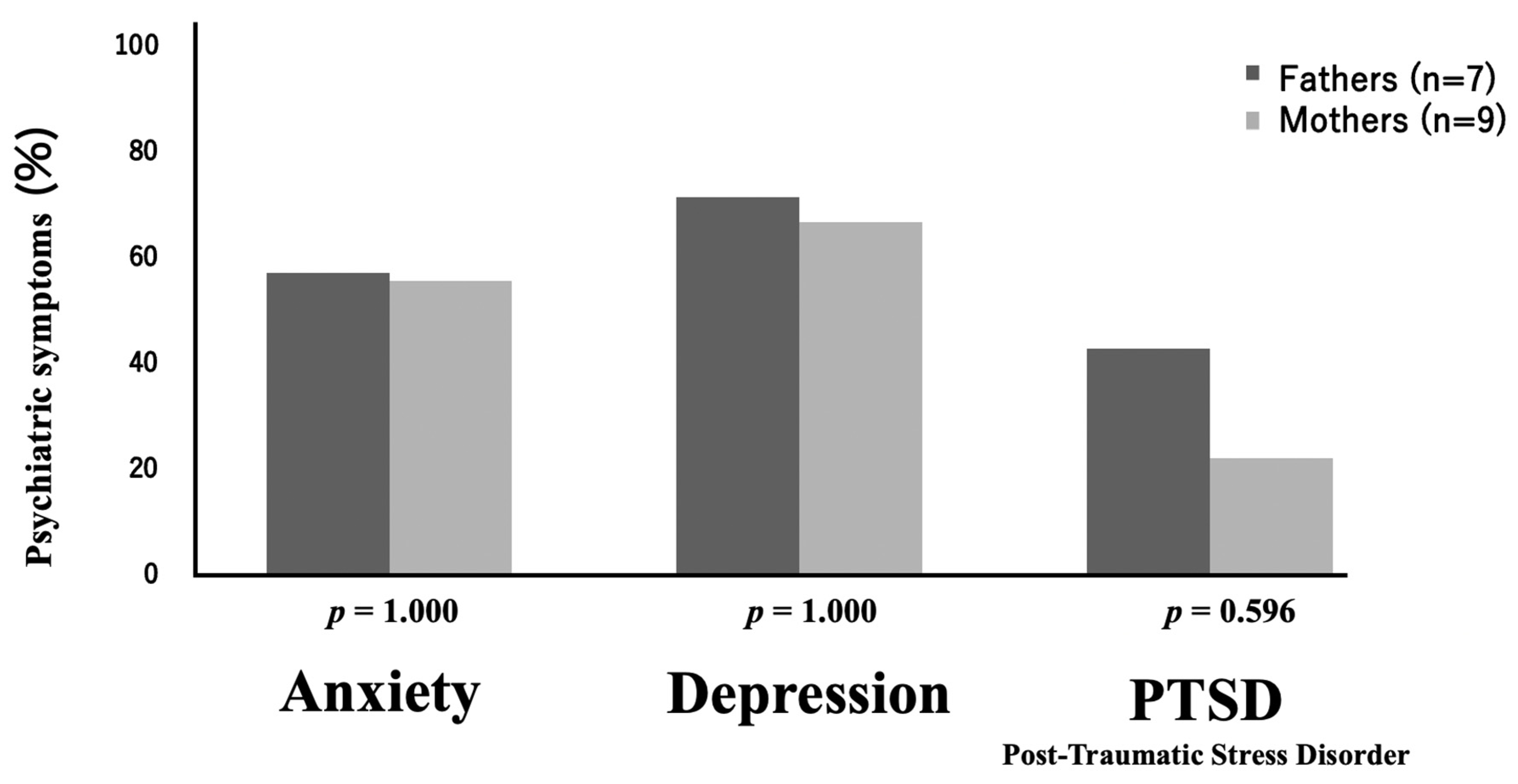

3.4. Psychiatric Symptoms One Month After Discharge

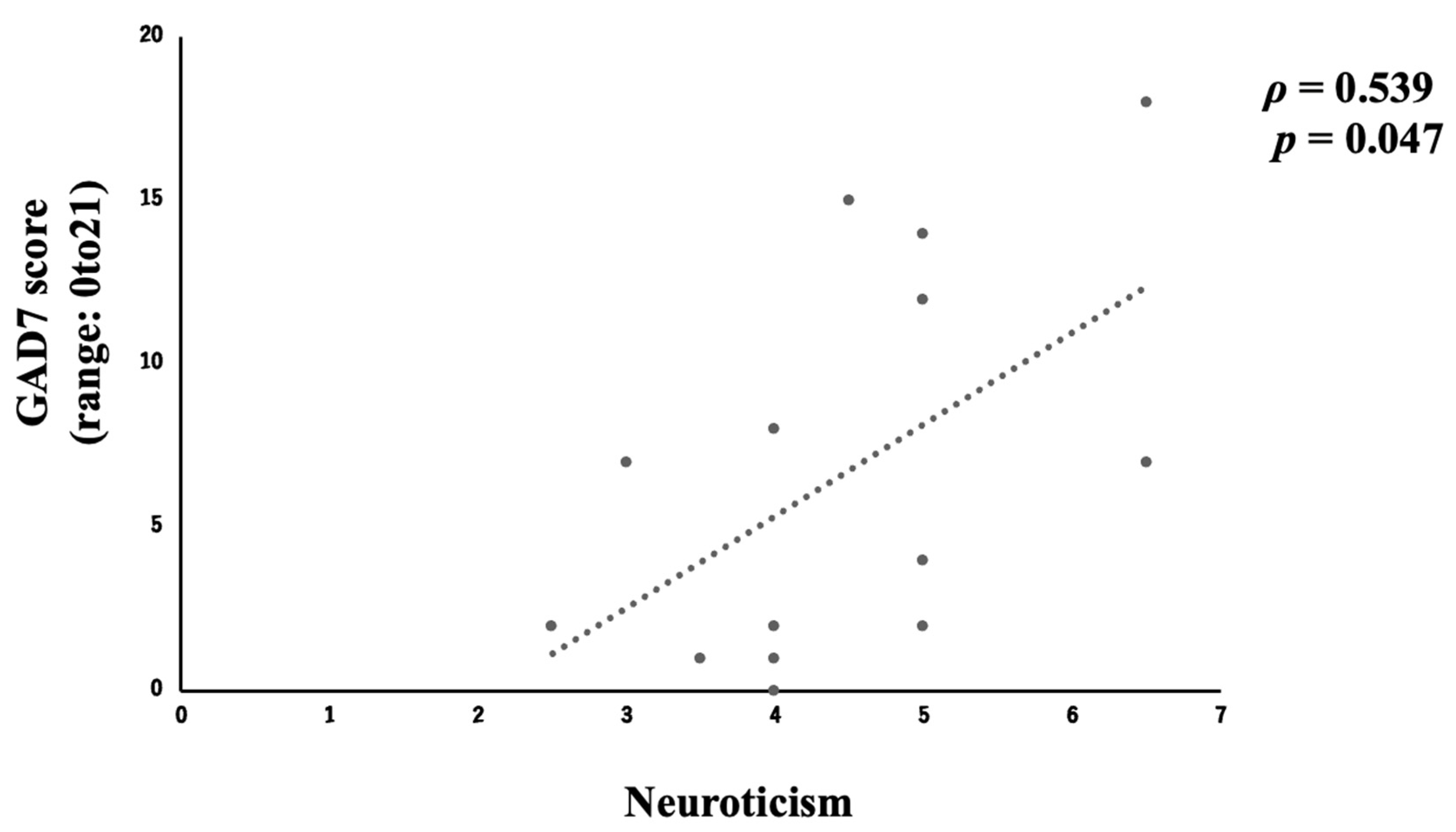

3.5. Relationship Between Personality Traits and Psychiatric Symptoms at One Month After Discharge

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine; Critical Care Workforce Analysis Project WG; Pediatric Intensive Care Committee, Future Planning Committee; Public Relations Committee; Specialist Institution (or System) Committee. Workforce surveillance in pediatric intensive care in Japan. J. Jpn. Soc. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 20, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Available online: https://www.jsicm.org/provider/picu.html (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Takei, K.; Shimizu, N.; Matsumoto, H.; Yagi, T.; Obara, S.; Sakai, H.; Mashiko, K. Critically Ill or Injured Children Should Be Centralized in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Nihon Kyukyu Igakukai Zasshi 2008, 19, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine Pediatric Intensive Care Committee. Survey of PICUs in Japan. J. Jpn. Soc. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 26, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.C.; Pinto, N.P.; Rennick, J.E.; Colville, G.; Curley, M.A.Q. Conceptualizing Post Intensive Care Syndrome in Children-The PICS-p Framework. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. J. Soc. Crit. Care Med. World Fed. Pediatr. Intensive Crit. Care Soc. 2018, 19, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronner, M.B.; Knoester, H.; Bos, A.P.; Last, B.F.; Grootenhuis, M.A. Follow-up after paediatric intensive care treatment: Parental posttraumatic stress. Acta Paediatr. 2008, 97, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Rey, R.; Alonso-Tapia, J.; Colville, G. Prediction of parental posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression after a child’s critical hospitalization. J. Crit. Care 2018, 45, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colville, G.; Pierce, C. Patterns of post-traumatic stress symptoms in families after paediatric intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishina, R.; Iwata, M.; Masuda, S.; Shimizu, S.; Nakata, S.; Murayama, Y.; Nishikawa, N.; Tsujio, Y.; Aoyama, M.; Anai, S.; et al. Anxiety, Depression, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Changes in Them Over Time in Parents with Children in Pediatric Intensive Care Units. J. Child Health 2020, 79, 140–151. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, N. Preventive strategies for mental health in Australia and issues for the implementation in Japan. Jpn. J. Prev. Psychiatry 2019, 4, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Nakai, Y. The Role of Psychosomatic Medicine in Public Health (Hygieiology): An Approach for Lifestyle-related Disease: An Approach for Lifestyle-related Disease. Nippon Eiseigaku Zasshi 2001, 56, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamian, H.; Lebherz-Eichinger, D. The role of psychosomatic medicine in intensive care units. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2018, 168, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maley, J.H.; Brewster, I.; Mayoral, I.; Siruckova, R.; Adams, S.; McGraw, K.A.; Piech, A.A.; Detsky, M.; Mikkelsen, M.E. Resilience in Survivors of Critical Illness in the Context of the Survivors’ Experience and Recovery. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, L.; Kristensen, K.K.; Laerkner, E. Parents’ experiences during and after their child’s stay in the paediatric intensive care unit—A qualitative interview study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021, 67, 103089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollack, M.M. PRISM III: An updated Pediatric Risk of Mortality score. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 24, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshio, A.; Abe, S.; Cutrone, P. Development, reliability, and validity of the Japanese version of Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI-J). Jpn. J. Personal. 2021, 21, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, K.; Maeda, S.; Miyaoka, H.; Kamijima, K.; Muramatsu, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Hosaka, M.; Miwa, Y.; Fuse, K.; Yoshimine, F.; et al. Performance of the Japanese version of the Patient Health GAD-7. Jpn. Soc. Psychosom. Med. 2010, 50, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu, K. An up-to-date letter in the Japanese version of PHQ, PHQ-9, PHQ-15. Grad. Sch. Clin. Psychol. Niigata Seiryo Univ. 2014, 7, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu, K.; Miyaoka, H.; Kamijima, K.; Muramatsu, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Hosaka, M.; Miwa, Y.; Fuse, K.; Yoshimine, F.; Mashima, I.; et al. Performance of the Japanese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (J-PHQ-9) for depression in primary care. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2018, 52, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Takebayashi, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Horikoshi, M. Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5: Psychometric properties in a Japanese population. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 247, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Keane, T.M.; Palmieri, P.A.; Marx, B.P.; Schnurr, P.P. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). 2013. Scale Available from the National Center for PTSD. Available online: www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Balluffi, A.; Kassam-Adams, N.; Kazak, A.; Tucker, M.; Dominguez, T.; Helfaer, M. Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 5, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuishi, Y.; Joseph, C.; Manning, H.H.; Enomoto, Y.; Munekawa, I.; Ikebe, R.; Tani, M.; Tanaka, N.; Bryan, J.M.; Shimojo, N.; et al. Empowerment of Parents in the Intensive Care: A multicentrevalidation study in Japan. Aust. Crit. Care 2025, 38, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.C.; Dennis, I.; Berger, Z.; Jones, R.; Rudd, H. Posttraumatic stress disorder following myocardial infarction: Personality, coping, and trauma exposure characteristics. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2011, 42, 393–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakši, N. The role of personality traits in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Psychiatr. Danub. 2012, 24, 256–266. [Google Scholar]

- Oshio, A. Progress & Application: Pāsonariti No Shinrigaku [Progress & Application: Personality Psychology]; Science Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Total | Father | Mother | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n = 19 (100) | 7 (36.8) | 12 (63.2) | |

| Age, median [IQR] Age group, n (%) | 20–29 30–39 40–49 | 32 [30.5–35.5] 2 (10.5) 15 (78.9) 2 (10.5) | 32 [30.75–35.25] | 32.5 [30.5–35] |

| Personality * (maximum score: 7), median [IQR] | Extraversion Agreeableness Conscientiousness Neuroticism Openness | 4 [3.25–5] 5 [4.5–5.5] 4 [3–4.5] 4 [4–5] 3.5 [3–4.5] | 3.5 [3.25–5.25] 5 [4.5–5.25] 4 [3.25–4] 4 [3.25–4] 4.5 [3–4.74] | 4 [3.75–5] 5.5 [4.5–5.5] 4 [3–4.5] 5 [4–5] 3.5 [3–4] |

| Variable | n = 17 | |

|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%)) Female, n (%)) | 8 (47.1) 9 (52.9) | |

| Age, n (%) | <1 month <1 year old 1–5 years old 5–10 years old | 2 (11.8) 7 (41.2) 6 (35.3) 2 (11.8) |

| Disease, n (%) | CVD CNS Respiratory Digestive system Other | 7 (41.2) 3 (17.6) 4 (23.5) 1 (5.9) 2 (12.5) |

| Admission category, n (%) | Elective surgery Emergency admission | 4 (23.5) 13 (76.5) |

| Days in PICU, n (%) | 7–10 days 10–30 days 30–60 days 60–100 days >100 days | 5 (29.4) 8 (47.1) 2 (11.8) 1 (5.9) 1 (5.9) |

| PRISM Ⅲ score *, median [IQR] | 18 [11–20.25] |

| Personality Traits | Anxiety n = 14 | Depression n = 14 | PTSD n = 14 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion | −0.282 | −0.399 | −0.438 |

| Agreeableness | −0.238 | −0.060 | −0.612 * |

| Conscientiousness | 0.318 | 0.127 | 0.467 |

| Neuroticism | 0.539 * | 0.318 | 0.327 |

| Openness | −0.333 | −0.312 | −0.309 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kotani, M.; Ikeda, M.; Aikawa, G.; Sakuramoto, H.; Ouchi, A.; Hoshino, H.; Boku, K.; Enomoto, Y.; Shimojo, N.; Inoue, Y. Relationship Between Personality of Parents and Pediatric Post-Intensive Care Syndrome for a Family in the PICU: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Pilot Study. Children 2025, 12, 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081056

Kotani M, Ikeda M, Aikawa G, Sakuramoto H, Ouchi A, Hoshino H, Boku K, Enomoto Y, Shimojo N, Inoue Y. Relationship Between Personality of Parents and Pediatric Post-Intensive Care Syndrome for a Family in the PICU: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Pilot Study. Children. 2025; 12(8):1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081056

Chicago/Turabian StyleKotani, Misaki, Mitsuki Ikeda, Gen Aikawa, Hideaki Sakuramoto, Akira Ouchi, Haruhiko Hoshino, Keishun Boku, Yuki Enomoto, Nobutake Shimojo, and Yoshiaki Inoue. 2025. "Relationship Between Personality of Parents and Pediatric Post-Intensive Care Syndrome for a Family in the PICU: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Pilot Study" Children 12, no. 8: 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081056

APA StyleKotani, M., Ikeda, M., Aikawa, G., Sakuramoto, H., Ouchi, A., Hoshino, H., Boku, K., Enomoto, Y., Shimojo, N., & Inoue, Y. (2025). Relationship Between Personality of Parents and Pediatric Post-Intensive Care Syndrome for a Family in the PICU: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Pilot Study. Children, 12(8), 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081056