The Role of Mobile Applications in Enhancing the Health-Related Quality of Life of Children with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

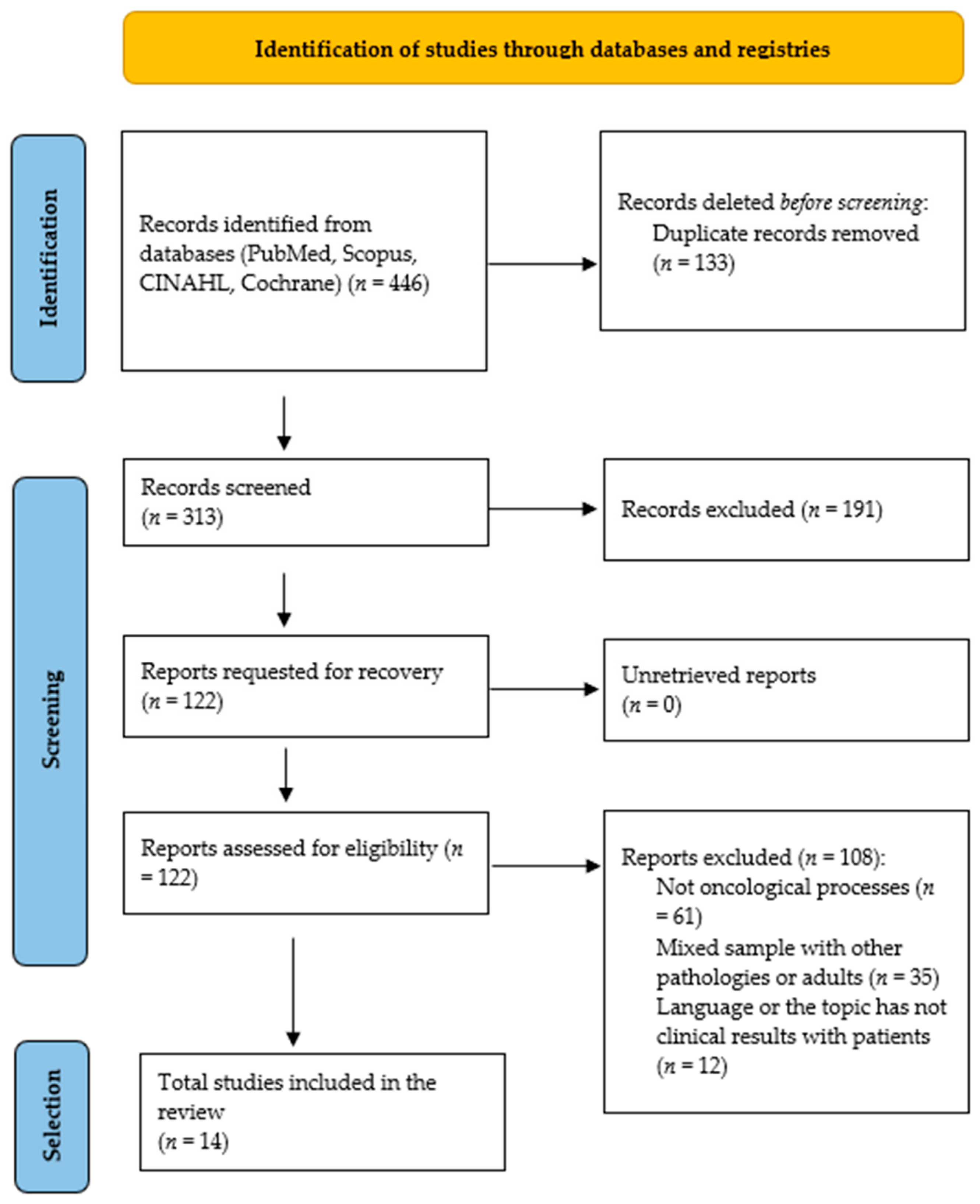

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.5. Methodological Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Results

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

4. Main Findings

4.1. Symptom-Specific Monitoring Through Mobile Applications

4.2. Mobile Apps for Pain Assessment and Management

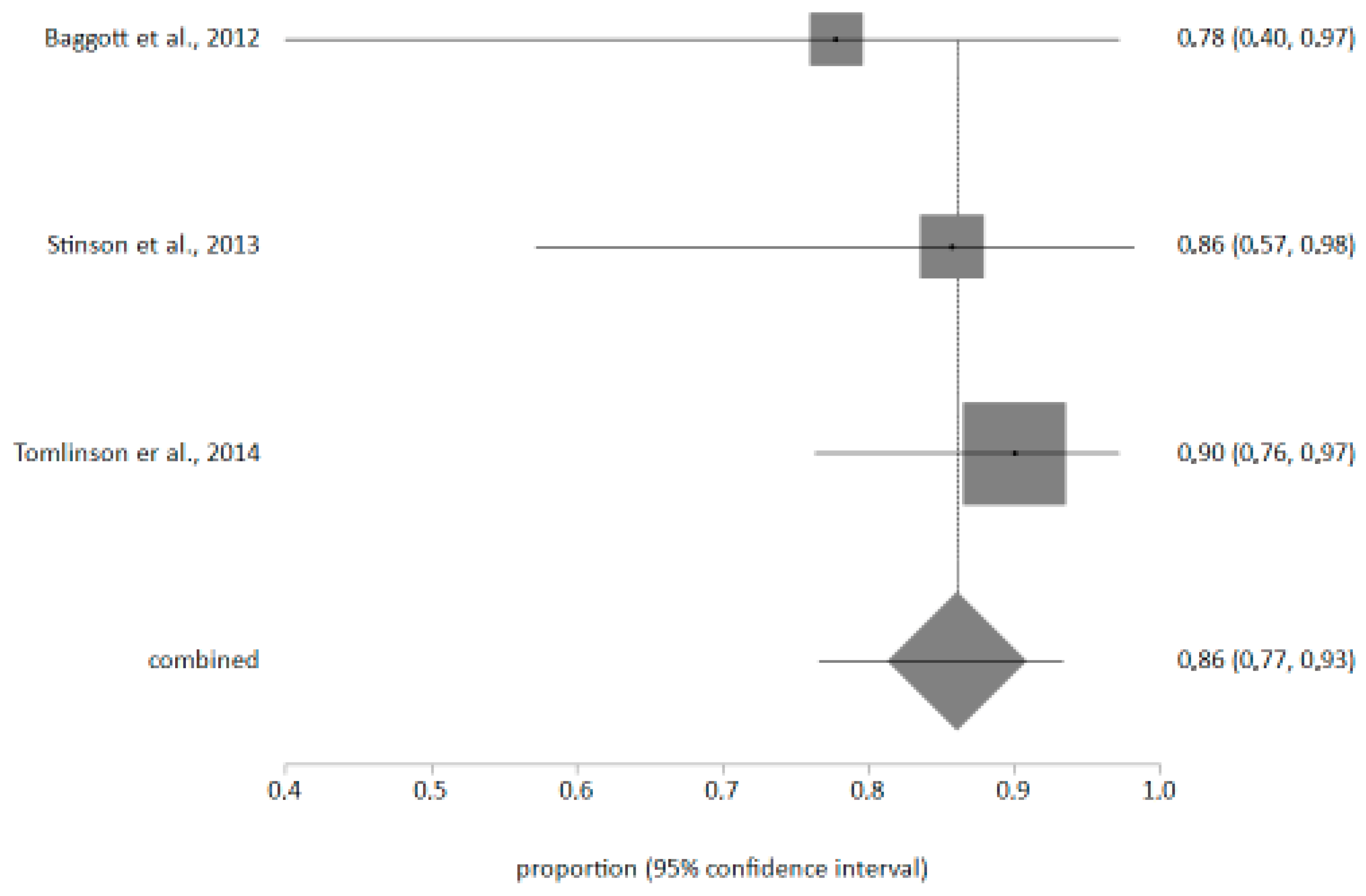

4.3. Meta-Analysis on the Ease of Use of Applications

4.4. Level of Evidence and Methodological Quality

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRQoL | health-related quality of life |

Appendix A

| Study | Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 |

| [17] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| [18] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| [19] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| [20] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| [21] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| [22] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| [23] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| [36] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

References

- Adjiri, A. Identifying and Targeting the Cause of Cancer is Needed to Cure Cancer. Oncol. Ther. 2016, 4, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, W.T.; Erdmann, F.; Newton, R.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Schüz, J.; Roman, E. Childhood cancer: Estimating regional and global incidence. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021, 71, 101662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Degner, L.F. Expectations and beliefs about children’s cancer symptoms: Perspectives of children with cancer and their families. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2003, 30, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, K.M.; Zelikovsky, N.; Schwartz, L.A. Physical symptoms, perceived social support, and affect in adolescents with cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2013, 31, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruland, C.M.; Hamilton, G.A.; Schjødt-Osmo, B. The complexity of symptoms and problems experienced in children with cancer: A review of the literature. J. Pain Symptom Manage 2009, 37, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, D.; Plenert, E.; Dadzie, G.; Loves, R.; Cook, S.; Schechter, T.; Dupuis, L.L.; Sung, L. Reasons for disagreement between proxy-report and self-report rating of symptoms in children receiving cancer therapies. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4165–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.E.; Carleton, M.E.; Cummings, B.M.; Noviski, N. Children’s Drawings With Narratives in the Hospital Setting: Insights Into the Patient Experience. Hosp. Pediatr. 2019, 9, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabali, H.K.; Irigoyen, M.M.; Nunez-Davis, R.; Budacki, J.G.; Mohanty, S.H.; Leister, K.P.; Bonner, R.L.J. Exposure and Use of Mobile Media Devices by Young Children. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beale, I.L.; Kato, P.M.; Marin-Bowling, V.M.; Guthrie, N.; Cole, S.W. Improvement in cancer-related knowledge following use of a psychoeducational video game for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, J.; Shah, N.; Jonassaint, J.; Harris, N.; Docherty, S.; Shaw, R. User-Centered App Design for Acutely Ill Children and Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 37, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diano, F.; Sica, L.S.; Ponticorvo, M. A Systematic Review of Mobile Apps as an Adjunct to Psychological Interventions for Emotion Dysregulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, H.; Asadi, F.; Mehrvar, A.; Nazemi, E.; Emami, H. Smartphone apps to help children and adolescents with cancer and their families: A scoping review. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, K.M.; Fizur, P.J. A review of mobile applications to help adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2015, 6, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiljer, D.; Shi, J.; Lo, B.; Sanches, M.; Hollenberg, E.; Johnson, A.; Abi-Jaoudé, A.; Chaim, G.; Cleverley, K.; Henderson, J.; et al. Effects of a Mobile and Web App (Thought Spot) on Mental Health Help-Seeking Among College and University Students: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldiss, S.; Taylor, R.M.; Soanes, L.; Maguire, R.; Sage, M.; Kearney, N.; Gibson, F. Working in collaboration with young people and health professionals. a staged approach to the implementation of a randomised controlled trial. J. Res. Nurs. 2011, 16, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggott, C.; Gibson, F.; Coll, B.; Kletter, R.; Zeltzer, P.; Miaskowski, C. Initial evaluation of an electronic symptom diary for adolescents with cancer. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2012, 1, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, J.N.; Jibb, L.A.; Nguyen, C.; Nathan, P.C.; Maloney, A.M.; Dupuis, L.L.; Gerstle, J.T.; Alman, B.; Hopyan, S.; Strahlendorf, C.; et al. Development and testing of a multidimensional iphone pain assessment application for adolescents with cancer. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, D.; Hesser, T.; Maloney, A.-M.; Ross, S.; Naqvi, A.; Sung, L. Development and initial evaluation of electronic Children’s International Mucositis Evaluation Scale (eChIMES) for children with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, J.N.; Jibb, L.A.; Nguyen, C.; Nathan, P.C.; Maloney, A.M.; Lee Dupuis, L.; Ted Gerstle, J.; Hopyan, S.; Alman, B.A.; Strahlendorf, C.; et al. Construct validity and reliability of a real-time multidimensional smartphone app to assess pain in children and adolescents with cancer. Pain 2015, 156, 2607–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibb, L.A.; Stevens, B.J.; Nathan, P.C.; Seto, E.; Cafazzo, J.A.; Johnston, D.L.; Hum, V.; Stinson, J.N. Implementation and preliminary effectiveness of a real-time pain management smartphone app for adolescents with cancer: A multicenter pilot clinical study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jibb, L.A.; Stevens, B.J.; Nathan, P.C.; Seto, E.; Cafazzo, J.A.; Johnston, D.L.; Hum, V.; Stinson, J.N. Perceptions of Adolescents With Cancer Related to a Pain Management App and Its Evaluation: Qualitative Study Nested Within a Multicenter Pilot Feasibility Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2018, 6, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.F.; Acevedo, A.M.; Gago-Masague, S.; Kain, A.; Yun, C.; Torno, L.; Jenkins, B.N.; Fortier, M.A. A pilot study of the preliminary efficacy of Pain Buddy: A novel intervention for the management of children’s cancer-related pain. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, J.D.H.P.; Schepers, S.A.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Mensink, M.; Huitema, A.D.; Tissing, W.J.E.; Michiels, E.M.C. Reducing pain in children with cancer at home: A feasibility study of the KLIK pain monitor app. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 7617–7626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, L.; Wakefield, C.E.; Mizrahi, D.; Diaz, C.; Cohn, R.J.; Signorelli, C.; Yacef, K.; Simar, D. A Digital Educational Intervention With Wearable Activity Trackers to Support Health Behaviors Among Childhood Cancer Survivors: Pilot Feasibility and Acceptability Study. JMIR Cancer 2022, 8, e38367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, L.A.; Newman, A.; Bernier Carney, K.M.; Wawrzynski, S.; Stegenga, K.; Chiu, Y.-S.; Jung, S.-H.; Iacob, E.; Lewis, M.; Linder, C.; et al. Symptoms and daily experiences reported by children with cancer using a game-based app. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 65, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, H.; Asadi, F.; Nazemi, E.; Mehrvar, A.; Yazdanian, A.; Emami, H. A Mobile Self-Management App (CanSelfMan) for Children With Cancer and Their Caregivers: Usability and Compatibility Study. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2023, 6, e43867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esplana, L.; Olsson, M.; Nilsson, S. ‘Do you feel well or unwell?’ A study on children’s experience of estimating their nausea using the digital tool PicPecc. J. Child Health Care 2023, 27, 654–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.D.H.P.; Schepers, S.A.; van Gorp, M.; Michiels, E.M.C.; Fiocco, M.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Tissing, W.J.E. Pain monitoring app leads to less pain in children with cancer at home: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2024, 130, 2339–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, J.; Kamkhoad, D.; Shaw, R.J.; Docherty, S.L.; Subramaniam, A.P.; Shah, N. Seriously ill pediatric patient, parent, and clinician perspectives on visualizing symptom data. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 1518–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utami, A.R.; Rahman, L.O.A. Efektifitas Aplikasi mHealth Terhadap Manajemen Nyeri Kanker Anak Usia Remaja: Literatur Review. J. Keperawatan 2020, 5, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jupp, J.C.Y.; Sultani, H.; Cooper, C.A.; Peterson, K.A.; Truong, T.H. Evaluation of mobile phone applications to support medication adherence and symptom management in oncology patients. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e27278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, A.-K.; Kaya, R.S.; Müller, C.; Andersen, B.; Langer, T.; Ingenerf, J. Design, implementation, and evaluation of a mobile application for patient empowerment and management of long-term follow-up after childhood cancer. Klin. Padiatr. 2015, 227, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, J.A.; Baker, K.S.; Moreno, M.A.; Whitlock, K.; Abbey-Lambertz, M.; Waite, A.; Colburn, T.; Chow, E.J. A Fitbit and Facebook mHealth intervention for promoting physical activity among adolescent and young adult childhood cancer survivors: A pilot study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, N.W.; Todd, K.E.; Indelicato, D.J.; Arce, S.H. Designing and developing a mobile application to prepare paediatric cancer patients for proton therapy. Des. Health 2018, 2, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasen, A.; Abildtoft, M.K.; Krogh, N.S.; Rechnitzer, C.; Brok, J.S.; Mathiasen, R.; Schmiegelow, K.; Dalhoff, K.P. Smartphone app to self-monitor nausea during pediatric chemotherapy treatment: User-centered design process. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2020, 8, e18564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year of Publication and Country | Type of Study | Sample and Objective | Intervention | Result and Conclusions | GR/EV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldiss et al., 2011 [17] United Kingdom | Case–control study | To develop an alarm system based on the severity of symptoms in paediatric patients undergoing Advanced Symptom Management System (ASyMS). N = 3 | The study had three phases, a first phase where they reflected on which symptoms were important to be aware of, a second phase where they reflected on their perceptions of the ASyMS system and a third phase where they designed an alarm system based on the severity of the symptoms. | The small number of participants did not allow for a meaningful analysis of the results, concluding that the self-care advice provided by the app was good and simple, but the alarm system that was attempted to be developed was not effective, thus stating the need for studies that allow for large-scale evaluations. | C/4 |

| Baggott et al., 2012 [18] EE.UU | Case–control study | To find out the usefulness of an electronic diary that assessed daily pain, nausea, vomiting, fatigue and sleep quality, designed for cancer patients (eDiary) through a mobile application. N = 11 | The adherence of the young people exceeded the expectations of the technical difficulties reported. | The usefulness of the diary for patients has been shown to improve the quality of care. It has been shown to improve patient management and the symptomatic relationship with cancer. | C/4 |

| Stinson et al., 2013 [19] Canada | Prospective descriptive study | Test the construct validity, reliability and feasibility of the Pain Squad application. N = 92 N = 14 | Two studies, the first one to assess construct validity and reliability of the application, had patients record their pain level twice a day. In the second, they recorded it 1 week before and 2 weeks after a surgical intervention. | The combined results of both studies support the app’s construct validity and reliability, demonstrating that it has good internal consistency. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that an electronic diary is advantageous for exploring pain levels in pediatric patients. | C/4 |

| Tomlinson et al., 2014 [20] Canadá | Descriptive clinical trial | To determine the ease or difficulty of using the application (eChIMES) to achieve better development and greater effectiveness of the usage options. N = 40 | Two phases were carried out: the first for the development and improvement of eChIMES (n = 10), and then to evaluate its ease of use, understandability, and suitability. Finally, the results were statistically analyzed using a descriptive analysis. | The results obtained were 100% easy or very easy to use, making it a good way to measure mucositis in children. It was considered innovative, a great idea, and easier than writing down one’s own symptoms or experiences. It was, therefore, concluded that eCHIMES was an easy-to-use and understandable application, but that it would be interesting to compare electronic versions with paper versions. | C/4 |

| Stinson et al., 2015 [21] Canada | Prospective descriptive study | To design and develop a gamified mobile app, called Pain Squad, that allows patients to assess their pain and provide an immediate reward system. N = 47 | Pain management drastically affected the social lives of participants, creating a disconnect between the healthcare system and the participants’ skills. | Participants with poor pain management demonstrated poor social role functioning, generating anxiety and stress in the parental relationship. The app demonstrated a development of the patient’s pain management skills. By improving social support with parents and improving pain education, it is concluded that the gamification of mobile healthcare can enable these patients to make better decisions about their treatment. | B/2b |

| Jibb et al., 2017 [22] Canada | Pilot study | To assess the implementation of an app (Pain Squad+) to inform a future randomized controlled trial (RCT) N = 38 | Use of Pain Squad+, a 22-item questionnaire that assesses pain (duration and location), causes, and treatment strategies. | This study demonstrated that the application improves pain intensity, responding positively to the hypothesis raised, suggesting that this application can be implemented for a future RCT intervention. | B/2b |

| Jibb et al., 2018 [23] Canada | Qualitative pilot study | To understand the perception of adolescents with cancer and to understand their adaptability to the application, improving the protocol. N = 40 | Participants agreed that the application would improve the protocol in a study with larger participants. | Although the results were approved by the participants, improvements in the intervention emerged in improving the quality of life of adolescents with cancer. Active participation in answering the questionnaire on symptom management and self-care improved quality of life, allowing them to seek help when necessary. Although the results were approved by the participants, improvements in the intervention emerged and there was an improvement in the quality of life of adolescents with cancer. | B/3b |

| Hunter et al., 2020 [24] USA | Qualitative pilot study | To evaluate the preliminary efficacy of Pain Buddy, an app for managing cancer-related pain in children. N = 48 | Pain Buddy allows for remote symptom monitoring and offers pain management coaching. A 60-day randomized controlled trial was conducted, in which children reported their pain through a digital diary. | Both groups showed a reduction in pain severity, but the intervention group reported fewer episodes of moderate to severe pain. It is considered an innovative and interactive application that can, therefore, help reduce both the severity and frequency of pain. | A/1b |

| Simon et al., 2021 [25] Netherlands | Feasibility study | To evaluate adherence, feasibility, and barriers and facilitators to the implementation of an app designed to monitor and track pain in children with cancer at home. N = 27 | The KLIK Pain Monitor app was used for three weeks. Children aged 8–18 years or their parents (for children aged 0–7 years) assessed pain twice daily using an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS-11). Clinically significant pain scores (≥4) were monitored by healthcare professionals from the hospital’s Pediatric Pain Service within 120 min (scores of 4–6) or 30 min (scores of 7–10). | Sixty-three percent of families (17 of 27) used the app daily during the three weeks, and 18.5% (5 of 27) reported pain scores twice daily during that period. 44.4% of children (12 of 27) reported at least one clinically significant pain score. In 70% of cases (14 of 20) with clinically significant pain scores, healthcare professionals followed up within the established timeframe. Most of the app’s features were positively evaluated by at least 70% of families and healthcare professionals, and non-feasible aspects were resolved. | C/4 |

| Ha et al., 2022 [26] Australia | Pilot study | To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the iBounce digital intervention, designed to educate and motivate survivors to participate in physical activity. N = 30 | A digital educational program with 10 modules, goal setting, and home-based physical activities monitored by an activity tracker. Participants were instructed to complete modules and log their physical activity. | High module completion rate, with the app (iBounce) considered feasible and acceptable. Technical difficulties were encountered with the activity trackers, but it is considered a useful model for delivering physical activity education and promotion to cancer survivors. | B/3b |

| Linder et al., 2022 [27] EE.UU | Estudio descriptivo | To evaluate the feasibility and usefulness of a game-based application for children with cancer to report their symptoms and daily experiences during treatment. N = 19 | The mobile application “Color Me Healthy” was used, designed to allow children to self-report their symptoms and daily experiences during cancer treatment. | The 19 children completed 107 days of app use. All reported symptoms at least once, and 14 reported at least one day with a moderate or greater symptom severity. The most frequent symptoms were pain (100% of children, 55.2% of days), fatigue (78.9% of children, 47.1% of days), and nausea (57.9% of children, 34.5% of days). Furthermore, reported daily experiences reflected children’s participation in usual childhood activities while also describing life with cancer, including symptoms. | C/4 |

| Mehdizadeh et al., 2023 [28] Irán | Pilot study | To evaluate the usability of the Can-SelfMan app, designed to improve communication between caregivers and healthcare providers. N = 44 | The app (Can-SelfMan) provides access to cancer information and symptom-tracking tools. It was used for three weeks, recording symptoms and asking questions answered by oncologists. | It proved to be a promising tool for improving care management, but there was a desire to improve interaction, so the application needs to be improved. | B/3b |

| Esplana et al., 2023 [29] Sweden | Pilot study | To evaluate children’s acceptability and experience of using the PicPecc app to manage nausea N = 8 | Use of the PicPecc app in children with cancer during an observation period, allowing self-reporting of nausea with an interactive digital interface. | The app improved children’s communication about their condition and allowed them to be more involved in their care. There was a 30% decrease in reported nausea compared to baseline, with user satisfaction at 85%. | B/3b |

| Simon et al., 2024 [30] Netherlands | Non-randomized clinical trial | To evaluate whether the use of a pain monitoring app reduces clinically significant pain in children with cancer at home. N = 94 | Use of the KLIK Pain Monitor app, which allows patients and their families to record moments of significant pain and receive real-time feedback from healthcare professionals. | The group using the app reported significantly less clinically significant pain and lower pain severity compared to the control group. Use of the app resulted in less clinically significant pain at home. Further research into the specific mechanisms of the app is recommended. | A/1b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Díaz, A.; Pérez-Ardanaz, B.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Canals Garzón, C.; Gómez-Salgado, J. The Role of Mobile Applications in Enhancing the Health-Related Quality of Life of Children with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children 2025, 12, 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070927

González-Díaz A, Pérez-Ardanaz B, Suleiman-Martos N, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Canals Garzón C, Gómez-Salgado J. The Role of Mobile Applications in Enhancing the Health-Related Quality of Life of Children with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children. 2025; 12(7):927. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070927

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Díaz, Ana, Bibiana Pérez-Ardanaz, Nora Suleiman-Martos, José L. Gómez-Urquiza, Cristina Canals Garzón, and Juan Gómez-Salgado. 2025. "The Role of Mobile Applications in Enhancing the Health-Related Quality of Life of Children with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Children 12, no. 7: 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070927

APA StyleGonzález-Díaz, A., Pérez-Ardanaz, B., Suleiman-Martos, N., Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Canals Garzón, C., & Gómez-Salgado, J. (2025). The Role of Mobile Applications in Enhancing the Health-Related Quality of Life of Children with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children, 12(7), 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070927