Mapping Barriers and Interventions to Diabetes Self-Management in Latino Youth: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of the Research Question

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategies

2.4. Screening and Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction and Analysis of Evidence

3. Results

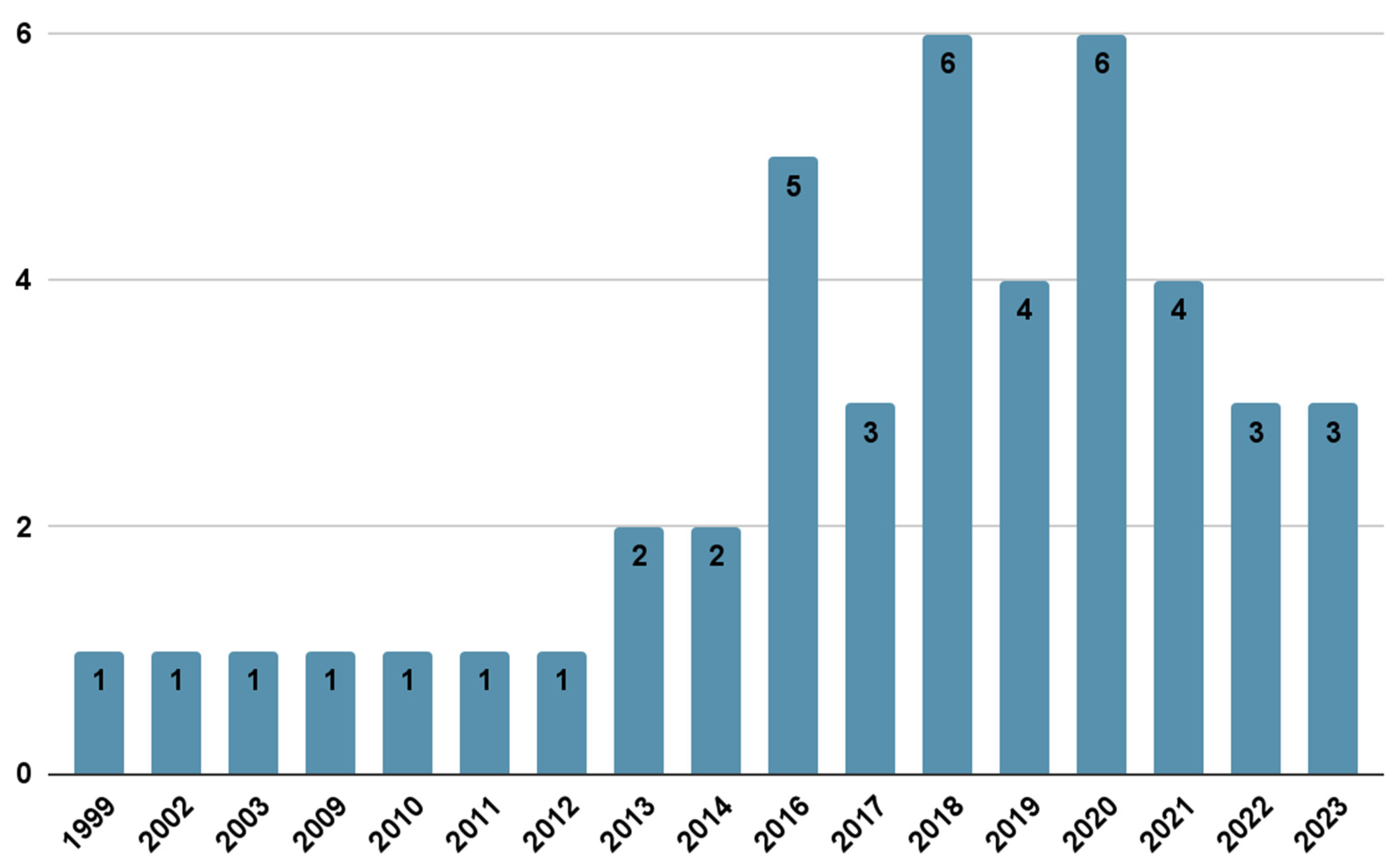

3.1. Included Studies Characteristics

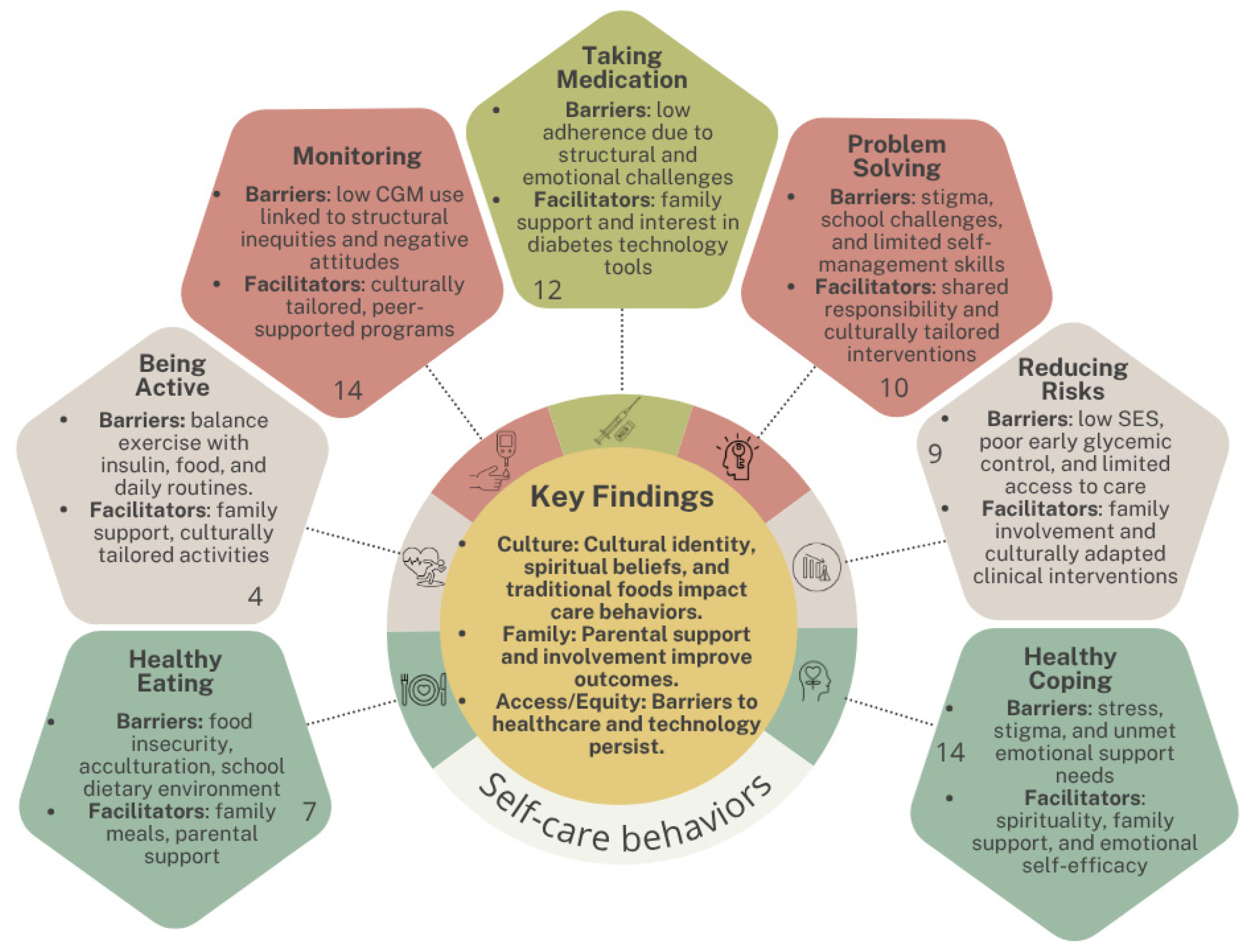

3.2. ADCES7 Key Areas

3.2.1. Healthy Eating

3.2.2. Being Active

3.2.3. Monitoring

3.2.4. Taking Medication

3.2.5. Problem Solving

3.2.6. Reducing Risks

3.2.7. Healthy Coping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PubMed | US National Library of Medicine |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| LILACS | Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature |

| ERIC | Education Resources Information Center |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| ADCES7 | Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists framework |

| CGM | Continuous glucose monitoring |

| HbA1c | Glycated hemoglobin |

| DSME | Diabetes self-management education |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| PCC | Population, concept and context |

| DeCS-MeSH | Descriptors in Health Sciences—Medical Subject Headings |

| T1D | Type 1 diabetes |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| VPG | Virtual peer group |

| MPR | Medication possession ratio |

| SLDC | Spanish Language Diabetes Clinic |

| SMA | Shared medical appointment |

| CoYoT1 | Colorado Young Adults with T1D |

| DKA | Diabetes ketoacidosis |

| YA | Young adults |

| NH | Non-Hispanic |

| SCI | Self-Care Inventory |

| CES-D | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale |

| DRS | Diabetes-related stigma |

| SS | Social stigma |

| IS | Internalized stigma |

| WNH | White Non-Hispanic |

| SI | Suicidal ideation |

| DRQOL | Diabetes-related quality of life |

| LEP | Limited English Proficiency |

| EADA | Escala de Autoeficacia para la Depresión en Adolescentes |

| ELDC | English Language Diabetes Clinic |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| QOL | Quality of life |

| BNH | Black Non-Hispanic |

Appendix A

Search Strategies

- PUBMED: (“Hispanic or Latino”[Mesh] OR Hispanic[tw] OR Latino[tw] OR Latinx[tw] OR Latina[tw]) AND (“Diabetes Mellitus”[Mesh] OR “Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1”[Mesh] OR “Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2”[Mesh] OR diabet*[tw] OR “type 1 diabetes”[tw] OR “type 2 diabetes”[tw]) AND (“Self Care”[Mesh] OR “Self-Management”[Mesh] OR “Culturally Competent Care”[Mesh] OR “Communication Barriers”[Mesh] OR “Shared Medical Appointments”[Mesh] OR “Patient Compliance”[Mesh] OR “Treatment Adherence and Compliance”[Mesh] OR “self care”[tw] OR “self-management”[tw]) AND (Adolescent[Mesh] OR adolescen*[tw] OR “Young Adult”[Mesh] OR Child[Mesh] OR child[tw] OR “Child, Preschool”[Mesh] OR preschool[tw] OR teenager*[tw] OR Youth[tw] OR Infant[Mesh] OR infan*[tw] OR Pediatrics[Mesh] OR pediatric*[tw])

- SCOPUS: (Hispanic OR Latino OR Latinx OR Latina) AND (“Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type 1” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type 2” OR diabet* OR “type 1 diabetes” OR “type 2 diabetes”) AND (“Self Care” OR “Self-Management” OR “Culturally Competent Care” OR “Communication Barriers” OR “Shared Medical Appointments” OR “Patient Compliance” OR “Treatment Adherence and Compliance”) AND (Adolescent OR adolescen* OR “Young Adult” OR Child OR “Child, Preschool” OR teenager* OR Youth OR Infant OR Pediatrics)

- The Cochrane Library: (Hispanic OR Latino OR Latinx OR Latina) AND (“Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type 1” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type 2” OR diabetes OR “type 1 diabetes” OR “type 2 diabetes”) AND (“Self Care” OR “Self-Management” OR “Culturally Competent Care” OR “Communication Barriers” OR “Shared Medical Appointments” OR “Patient Compliance” OR “Treatment Adherence and Compliance” OR self care OR self-management) AND (Adolescent OR adolescen OR “Young Adult” OR Child OR “Child, Preschool” OR preschool OR teenager OR Youth OR Infant OR Pediatrics OR pediatric)

- LILACS: (Hispanic OR Latino OR Latinx OR Latina) AND (“Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type 1” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type 2” OR diabetes OR “type 1 diabetes” OR “type 2 diabetes”) AND (“Self Care” OR “Self-Management” OR “Culturally Competent Care” OR “Communication Barriers” OR “Shared Medical Appointments” OR “Patient Compliance” OR “Treatment Adherence and Compliance” OR self care OR self-management) AND (Adolescent OR adolescen OR “Young Adult” OR Child OR “Child, Preschool” OR preschool OR teenager OR Youth OR Infant OR Pediatrics OR pediatric)

- CINAHL: (Hispanic or Latino OR Hispanic OR Latino OR Latinx OR Latina) AND (Diabetes Mellitus OR Diabetes Mellitus Type 1 OR Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 OR diabet* OR type 1 diabetes OR type 2 diabetes) AND (Self Care OR Self-Management OR Culturally Competent Care OR Communication Barriers OR Shared Medical Appointments OR Patient Compliance OR Treatment Adherence and Compliance OR self care OR self-management) AND (Adolescent OR adolescen* OR Young Adult OR Child OR child OR Child, Preschool OR preschool OR teenager* OR Youth OR Infant OR Pediatrics OR pediatric*)

- Web of Science: (Hispanic OR Latino OR Latinx OR Latina) AND (“Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type 1” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type 2” OR diabet* OR “type 1 diabetes” OR “type 2 diabetes”) AND (“Self Care” OR “Self-Management” OR “Culturally Competent Care” OR “Communication Barriers” OR “Shared Medical Appointments” OR “Patient Compliance” OR “Treatment Adherence and Compliance”) AND (Adolescent OR adolescen* OR “Young Adult” OR Child OR “Child, Preschool” OR teenager* OR Youth OR Infant OR Pediatrics)

- ERIC: (Hispanic OR Latino OR Latinx OR Latina) AND (“Diabetes Mellitus” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type 1” OR “Diabetes Mellitus Type 2” OR diabetes OR “type 1 diabetes” OR “type 2 diabetes”) AND (“Self Care” OR “Self-Management” OR “Culturally Competent Care” OR “Communication Barriers” OR “Shared Medical Appointments” OR “Patient Compliance” OR “Treatment Adherence and Compliance” OR self care OR self-management) AND (Adolescent OR adolescen OR “Young Adult” OR Child OR “Child, Preschool” OR preschool OR teenager OR Youth OR Infant OR Pediatrics OR pediatric)

References

- Butayeva, J.; Ratan, Z.A.; Downie, S.; Hosseinzadeh, H. The impact of health literacy interventions on glycemic control and self-management outcomes among type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. J. Diabetes 2023, 15, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tönnies, T.; Brinks, R.; Isom, S.; Dabelea, D.; Divers, J.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Lawrence, J.M.; Pihoker, C.; Dolan, L.; Liese, A.D.; et al. Projections of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Burden in the U.S. Population Aged <20 Years Through 2060: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joiner, K.L.; DeJonckheere, M.; Whittemore, R.; Grey, M. Perceptions and experiences of living with type 1 diabetes among Latino adolescents and parents with limited English proficiency. Res. Nurs. Health 2020, 43, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacha, F.; Cheng, P.; Gal, R.L.; Beaulieu, L.C.; Kollman, C.; Adolph, A.; Shoemaker, A.H.; Wolf, R.; Klingensmith, G.J.; Tamborlane, W.V. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Comorbidities in Youth with Type 2 Diabetes in the Pediatric Diabetes Consortium (PDC). Diabetes Care 2021, dc210143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, M.D.; Malabu, U.H.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.O.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. Enablers and barriers to effective diabetes self-management: A multi-national investigation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanns, N.; Ehrmann, D.; Finke-Groene, K.; Kulzer, B. Trends in diabetes self-management education: Where are we coming from and where are we going? A narrative review. Diabet. Med. 2020, 37, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, B.; Wynter, K.; Rawson, H.A.; Skouteris, H.; Ivory, N.; Brumby, S.A. Self-management of diabetes and associated comorbidities in rural and remote communities: A scoping review. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2021, 27, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.; Kappagoda, M.; Boseman, L.; Cloud, L.K.; Croom, B. Advancing Diabetes-Related Equity Through Diabetes Self-Management Education and Training: Existing Coverage Requirements and Considerations for Increased Participation. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2020, 26 (Suppl. S2), S37–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Briggs, F.; Gemmell, L. Problem Solving in Diabetes Self-management and Control. Diabetes Educ. 2007, 33, 1032–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, S.L.; Schumann, K.P.; Hill-Briggs, F. Problem solving interventions for diabetes self-management and control: A systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 100, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhoma, D.E.; Soko, C.J.; Bowrin, P.; Manga, Y.B.; Greenfield, D.; Househ, M.; Li, Y.-C.; Iqbal, U. Digital interventions self-management education for type 1 and 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 210, 106370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theng, Y.L.; Lee, J.W.; Patinadan, P.V.; Foo, S.S. The Use of Videogames, Gamification, and Virtual Environments in the Self-Management of Diabetes: A Systematic Review of Evidence. Games Health J. 2015, 4, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, E.C.L.; Quirk, H.; Glazebrook, C.; Randell, T.; Blake, H. Impact of technology-based interventions for children and young people with type 1 diabetes on key diabetes self-management behaviours and prerequisites: A systematic review. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2019, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wei, X.; Zheng, J.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Y. Financial incentives in the management of diabetes: A systematic review. Cost. Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2024, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goff, Z.; Palmer, C.; Jadhakhan, F.; Barber, A. Are diabetes self-management interventions delivered in the psychiatric inpatient setting effective? A protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, K.; Frazer, S.F.; Dempster, M.; Hamill, A.; Fleming, H.; McCorry, N.K. Psychological factors associated with diabetes self-management among adolescents with Type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1749–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualula, N.A.; Jacobsen, K.H.; Milligan, R.A.; Rodan, M.F.; Conn, V.S. Evaluating Diabetes Educational Interventions with a Skill Development Component in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review Focusing on Quality of Life. Diabetes Educ. 2016, 42, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.H.; Dawson, S.; Wheeler, J.; Hamilton-Shield, J.; Barrett, T.G.; Redwood, S.; Litchfield, I.; Greenfield, S.M.; Searle, A.; the Diversity in Diabetes (DID). Views of children with diabetes from underserved communities, and their families on diabetes, glycaemic control and healthcare provision: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Diabet. Med. 2023, 40, e15197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J.A.; Billimek, J.; Lee, J.-A.; Sorkin, D.H.; Olshansky, E.F.; Clancy, S.L.; Evangelista, L.S. Effect of diabetes self-management education on glycemic control in Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S.; Swan, M.; Smaldone, A. Does diabetes self-management education in conjunction with primary care improve glycemic control in Hispanic patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Educ. 2015, 41, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.; O’Connell, S.S.; Thomas, C.; Chimmanamada, R. Telehealth Interventions to Improve Diabetes Management Among Black and Hispanic Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Racial. Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 9, 2375–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, A.P.; Fortmann, A.L.; Savin, K.; Clark, T.L.; Gallo, L.C. Effectiveness of Diabetes Self-Management Education Programs for US Latinos at Improving Emotional Distress: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Educ. 2019, 45, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caban, A.; Walker, E.A. A systematic review of research on culturally relevant issues for Hispanics with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2006, 32, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Davies, E.L.; Peters, M.D.J.; Tricco, A.C.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; Munn, Z. Undertaking a scoping review: A practical guide for nursing and midwifery students, clinicians, researchers, and academics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2102–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. ADCES7 Self-Care Behaviors. Available online: https://www.adces.org/diabetes-education-dsmes/adces7-self-care-behaviors (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, É.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addala, A.; Ding, V.; Zaharieva, D.P.; Bishop, F.K.; Adams, A.S.; King, A.C.; Johari, R.; Scheinker, D.; Hood, K.K.; Desai, M.; et al. Disparities in Hemoglobin A1c Levels in the First Year After Diagnosis Among Youths with Type 1 Diabetes Offered Continuous Glucose Monitoring. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 3, e238881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, A.O.; Rascati, K.L.; Lawson, K.A.; Strassels, S.A. Adherence to oral antidiabetic medications in the pediatric population with type 2 diabetes: A retrospective database analysis. Clin. Ther. 2012, 34, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Kanapka, L.G.; Raymond, J.K.; Walker, A.; Gerard-Gonzalez, A.; Kruger, D.; Redondo, M.J.; Rickels, M.R.; Shah, V.N.; Butler, A.; et al. Racial-Ethnic Inequity in Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e2960–e2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Schechter, C.; Gonzalez, J.; Long, J.A. Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Diabetes Technology use Among Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2021, 23, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baboun, D.; Solano, N.; Del Toro, V.; Alvarez-Salvat, R.; Granados, A.; Carrillo-Iregui, A. Technology use and clinical outcomes in a racial-ethnic minority cohort of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 36, 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisno, D.I.; Reid, M.W.; Pyatak, E.A.; Garcia, J.F.; Salcedo-Rodriguez, E.; Sanchez, A.T.; Fox, D.S.; Hiyari, S.; Fogel, J.L.; Marshall, I.; et al. Virtual Peer Groups Reduce HbA1c and Increase Continuous Glucose Monitor Use in Adolescents and Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2023, 25, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolter, A.; Main, A.; Wiebe, D.J. Division of Type 1 Diabetes Responsibility in Latinx and Non-Latinx White Mother-Adolescent Dyads. J. Behav. Med. 2022, 45, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortsov, A.; Liese, A.D.; Bell, R.A.; Dabelea, D.; D’Agostino, R.B., Jr.; Hamman, R.F.; Klingensmith, G.J.; Lawrence, J.M.; Maahs, D.M.; McKeown, R.; et al. Correlates of dietary intake in youth with diabetes: Results from the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodar, K.E.; Davis, E.M.; Lynn, C.; Starr-Glass, L.; Lui, J.H.L.; Sanchez, J.; Delamater, A.M. Comprehensive psychosocial screening in a pediatric diabetes clinic. Pediatr. Diabetes 2021, 22, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.M.; Weller, B.E.; Yi-Frazier, J.P.; Fegan-Bohm, K.; Anderson, B.; Pihoker, C.; Hilliard, M.E. Diabetes-Specific and General Life Stress and Glycemic Outcomes in Emerging Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: Is Race/Ethnicity a Moderator? J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2017, 42, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.; Yeh, M.Y.; Raymond, J.K.; Geffner, M.E.; Ryoo, J.H.; Chao, L.C. Glycemic control in youth-onset type 2 diabetes correlates with weight loss. Pediatr. Diabetes 2020, 21, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Ramos, G.; Cumba-Avilés, E.; Quiles-Jiménez, M. “They called me a terrorist”: Social and internalized stigma in Latino youth with type 1 diabetes. Health Psychol. Rep. 2018, 6, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholl, M.C.; Valenzuela, J.M.; Lit, K.; DeLucia, C.; Shoulberg, A.M.; Rohan, J.M.; Pendley, J.S.; Dolan, L.; Delamater, A.M. Featured Article: Comparison of Diabetes Management Trajectories in Hispanic versus White Non-Hispanic Youth with Type 1 Diabetes across Early Adolescence. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos-Macias, A.R.; Macias, S.R.; Kaufman, E.; Skipper, B.; Kalishman, N. Relationship between glycemic control, ethnicity and socioeconomic status in Hispanic and white non-Hispanic youths with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr. Diabetes 2003, 4, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, K.K.; Baranowski, T.; Anderson, B.J.; Bansal, N.; Redondo, M.J. Psychosocial aspects of type 1 diabetes in Latino- and Asian-American youth. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 80, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, H.T.; Pirraglia, E.; Huang, E.S.; Wan, W.; Pascual, A.B.; Jensen, R.J.; Gonzalez, A.G. Cost and healthcare utilization analysis of culturally sensitive, shared medical appointment model for Latino children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2021, 22, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Ramírez, G.; Cumba-Avilés, E. Factors Associated with Suicidal Ideation and Quality of Life in Adolescents from Puerto Rico with Type 1 Diabetes. P. R. Health Sci. J. 2018, 37, 19–21. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5892187/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Hsin, O.; La Greca, A.M.; Valenzuela, J.; Moine, C.T.; Delamater, A. Adherence and glycemic control among Hispanic youth with type 1 diabetes: Role of family involvement and acculturation. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 35, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.F.; Perfect, M.M. Glycemic control influences on academic performance in youth with Type 1 diabetes. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 34, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, A.; Kho, C.; Miramontes, M.; Wiebe, D.J.; Çakan, N.; Raymond, J.K. Parents’ Empathic Accuracy: Associations with Type 1 Diabetes Management and Familism. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2022, 47, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, A.; Wiebe, D.J.; Croom, A.R.; Sardone, K.; Godbey, E.; Tucker, C.; White, P.C. Associations of parent-adolescent relationship quality with type 1 diabetes management and depressive symptoms in Latino and Caucasian youth. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 1104–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, D.; Wiebe, D. The Role of Socioeconomic Status in Latino Health Disparities Among Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2020, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, D.; Wiebe, D.J.; Barranco, C.; Barba, J. The Stress and Coping Context of Type 1 Diabetes Management Among Latino and Non-Latino White Early Adolescents and Their Mothers. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017, 42, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagán-Torres, O.M.; Cumba-Avilés, E.; Matos-Melo, A.L. Psychometric properties of the Escala de Autoeficacia para la Depresión en Adolescentes (EADA) among Latino youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetol. Int. 2018, 10, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palau-Collazo, M.M.; Rose, P.; Sikes, K.; Kim, G.; Benavides, V.; Urban, A.; Weinzimer, S.; Tamborlane, W. Effectiveness of a spanish language clinic for Hispanic youth with type 1 diabetes. Endocr. Pract. 2013, 19, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, E.C.; Lee, J.; Reiboldt, W. Responses of Youth with Diabetes and Their Parents to the Youth Eating Perceptions Survey: What Helps Kids with Diabetes Eat Better? Child. Obes. Nutr. 2013, 5, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, A.B.; Pyle, L.; Nieto, J.; Klingensmith, G.J.; Gonzalez, A.G. Novel, culturally sensitive, shared medical appointment model for Hispanic pediatric type 1 diabetes patients. Pediatr. Diabetes 2019, 20, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piven, E.; Duran, R. Reduction of non-adherent behaviour in a Mexican-American adolescent with type 2 diabetes. Occup. Ther. Int. 2014, 21, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyatak, E.A.; Carandang, K.; Vigen, C.; Blanchard, J.; Sequeira, P.A.; Wood, J.R.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Whittemore, R.; Peters, A.L. Resilient, Empowered, Active Living with Diabetes (REAL Diabetes) study: Methodology and baseline characteristics of a randomized controlled trial evaluating an occupation-based diabetes management intervention for young adults. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2017, 54, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, S.J.; Coakley, A.; Vigers, T.; Pyle, L.; Forlenza, G.P.; Alonso, T. Pediatric Medicaid Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Benefit From Continuous Glucose Monitor Technology. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2021, 15, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.K.; Reid, M.W.; Fox, S.; Garcia, J.F.; Miller, D.; Bisno, D.; Fogel, J.L.; Krishnan, S.; Pyatak, E.A. Adapting home telehealth group appointment model (CoYoT1 clinic) for a low SES, publicly insured, minority young adult population with type 1 diabetes. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 88, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitblat, L.; Whittemore, R.; Weinzimer, S.A.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Sadler, L.S. Life with Type 1 Diabetes: Views of Hispanic Adolescents and Their Clinicians. Diabetes Educ. 2016, 42, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, K.; Bartz, S.K.; Lyons, S.K.; DeSalvo, D.J. Diabetes Device Use and Glycemic Control among Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: A Single-Center, Cross-Sectional Study. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 5162162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St George, S.M.; Delamater, A.M.; Pulgaron, E.R.; Daigre, A.; Sanchez, J. Access to and Interest in Using Smartphone Technology for the Management of Type 1 Diabetes in Ethnic Minority Adolescents and Their Parents. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2016, 18, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streisand, R.; Respess, D.; Overstreet, S.; Gonzalez de Pijem, L.; Chen, R.S.; Holmes, C. Brief report: Self-care behaviors of children with type 1 diabetes living in Puerto Rico. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2002, 27, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan-Bolyai, S. Familias Apoyadas: Latino families supporting each other for diabetes care. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2009, 24, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.J.; La Greca, A.; Valenzuela, J.M.; Hsin, O.; Delamater, A.M. Satisfaction with the Health Care Provider and Regimen Adherence in Minority Youth with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2016, 23, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, D.; Flores Garcia, J.; Fogel, J.L.; Wee, C.P.; Reid, M.W.; Raymond, J.K. Diabetes Technology Experiences Among Latinx and Non-Latinx Youth with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2022, 16, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.; Wiebe, D.J.; Main, A.; Lee, A.G.; White, P.C. Adolescent Information Management and Parental Knowledge in Non-Latino White and Latino Youth Managing Type 1 Diabetes. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajravelu, M.E.; Hitt, T.A.; Amaral, S.; Levitt Katz, L.E.; Lee, J.M.; Kelly, A. Real-world treatment escalation from metformin monotherapy in youth-onset Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A retrospective cohort study. Pediatr. Diabetes 2021, 22, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamater, A.M.; Shaw, K.H.; Applegate, E.B.; Pratt, I.A.; Eidson, M.; Lancelotta, G.X.; Gonzalez-Mendoza, L.; Richton, S. Risk for metabolic control problems in minority youth with diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, T.H.; Smith, J.A.; Patil, O.; Willi, S.M.; Hawkes, C.P. Racial disparities in treatment and outcomes of children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2020, 22, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lado, J.J.; Lipman, T.H. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Incidence, Treatment, and Outcomes of Youth with Type 1 Diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 45, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, G.; Montgomery, S.B.; Beeson, L.; Bahjri, K.; Shulz, E.; Firek, A.; De Leon, M.; Cordero-MacIntyre, Z. En Balance: The effects of Spanish diabetes education on physical activity changes and diabetes control. Diabetes Educ. 2012, 38, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halgunseth, L.C.; Ispa, J.M.; Rudy, D. Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 1282–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortmann, A.L.; Savin, K.L.; Clark, T.L.; Philis-Tsimikas, A.; Gallo, L.C. Innovative Diabetes Interventions in the U.S. Hispanic Population. Diabetes Spectr. 2019, 32, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference, Country/State, Objective | Study Design, Latino Participants and Type of Diabetes | Main Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addala et al. (2023) [30] California, United States of America To determine whether HbA1c decreases differed by ethnicity and insurance status among a cohort of youths newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (T1D) and provided with CGM. | Prospective, longitudinal cohort study 29 Latino participants (21.48%), Mean age: 9.7 years (IQR, 6.8–12.7) T1D | Hispanic participants had higher HbA1c levels than non-Hispanic participants at all time points post-diagnosis (6, 9, and 12 months). The increase in HbA1c at 6, 9, and 12 months for Hispanic youths was 0.63% (significant), with a 1.39% HbA1c difference at 12 months. At 12 months, 47% of Hispanic participants achieved an HbA1c < 7.5%, and 47% achieved <7.0%, showing improvement over the historical cohort. | Single-site study design, limiting generalizability; exploratory nature, focusing on ethnicity and insurance status without evaluating racial differences (e.g., absence of non-Hispanic Black participants); small sample size; inability to stratify HbA1c changes by ethnicity or insurance; digital divide impacting CGM data uploads, especially in Hispanic youths. |

| Adeyemi et al. (2012) [31] TX, United States of America To describe oral antidiabetic medications use and assess trends in medication adherence and persistence among Texas pediatric Medicaid patients. | Retrospective, descriptive study 1869 Latino participants (60%), Median age 14.2 years (SD, 2.3) Type 2 diabetes (T2D) | Medication Adherence: The mean medication possession ratio (MPR) was 44.69% (SD: 27.06%). White participants had the highest adherence (50.04%), followed by Black participants (44.24%) and Hispanic participants (42.50%). Males had higher adherence (47.47%) than females (43.29%). Younger patients (ages 10–12) had the highest adherence (48.82%). Persistence: The mean time to non-persistence (gap of 45 days in medication use) was 108 days (SD: 86 days). Persistence declined with age, with older adolescents (16–18) having shorter persistence. | Lack of generalizability due to the study design; MPR used as a proxy for adherence, which may only reflect medication refills; other covariates not described due to retrospective design; some treatments may have been prescribed for obesity, not T2D. |

| Agarwal et al. (2020) [32] California, Florida, Texas, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Colorado, United States of America To describe racial-ethnic disparities among young adults (YA) with T1D and identify drivers of glycemic disparity other than socioeconomic status | Cross-sectional multicenter Study 103 Latino participants (34%) Median age 20 years (IQR, 19–20) T1D | The mean HbA1c for Hispanic youth was 9.3 ± 2.2%. Compared to White participants, Hispanic participants had significantly worse socioeconomic indicators, including lower annual household income, lower education, lower social status, and higher neighborhood poverty. In total, 39% of Hispanic participants used an insulin pump, compared to 72% of White participants, and 37% had ever used a CGM, compared to 71% of White participants. After adjusting for socioeconomic status, Hispanic youth showed similar glycemic control to White youth, with no significant differences. | The study was cross-sectional, limiting causal interpretations. The use of English-only materials may have led to the presence of a more educated and acculturated Hispanic population in the sample. Additionally, more Hispanic participants were from pediatric centers, which may have provided better support compared to other settings. |

| Agarwal et al. (2021) [33] California, Florida, Texas, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Colorado, United States of America (1) To measure the degree of racial-ethnic disparity in insulin pump and CGM use between NH White, NH Black, and Hispanic YA; (2) to examine how multiple factors related to SES contributed to disparities; (3) to determine how patient-reported outcomes such as healthcare factors (care setting, clinic attendance) and diabetes self-management (diabetes numeracy, self-monitoring of blood glucose, and Self-Care Inventory [SCI] score) accounted for disparities. | Cross-sectional multicenter study 103 Latino participants (34%) Median age: 20 years (IQR, 19–20) T1D | Hispanic participants had lower rates of insulin pump (39%) and CGM use (37%) compared to WNH participants (72% and 71%, respectively). After adjusting for SES, healthcare factors, and self-management, the adjusted rates for insulin pump use were 49% and those for CGM use were 58% in the Hispanic group. | The study was cross-sectional, limiting causal conclusions. The use of self-reported data may not fully reflect actual behaviors. The study did not assess factors such as racial discrimination or implicit bias, which may influence disparities in technology use. |

| Baboun et al. (2023) [34] Florida, United States of America To examine the impact of CGM use and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion on glycemic control in a racial-ethnic minority cohort of children and adolescents with T1D. | Cross-sectional study 111 Latino participants (79%) Mean age: 12.97 years (SD, 3.25) for technology users and 14.09 years (SD, 3.56) for technology non-users T1D | Technology users had significantly better glycemic control than technology non-users, with a mean HbA1c of 8.40% compared to 9.60% (p = 0.0024). Among the technology non-users, Hispanic participants had better glycemic control than Black participants (mean HbA1c of 9.19% vs. 11.26%, p = 0.0385). No significant differences in HbA1c were found between Hispanic and Black participants in the technology groups (CGM + MDI, FS + CSII). A total of 27 patients (19%) achieved the ADA’s recommended HbA1c target of less than 7.0%. | The study had an imbalanced representation of ethnic groups, with a disproportionate number of Black and White patients compared to Hispanic patients. There was an absence of data on disordered eating behaviors (leading to insulin misuse for weight management) and depression. Additionally, there was no systematic method to assess the socioeconomic status (SES) of each patient and pair this information with HbA1c levels. |

| Bisno et al. (2023) [35] California, United States of America To examine the association between attending virtual peer group appointments led by a young adult with T1D and improvements in health-related outcomes within the context of a larger randomized controlled trial of Colorado Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes (CoYoT1) Clinic, known as CoYoT1 in California. | Longitudinal, experimental study 34 Latino participants (50%) Mean age: 18.15 years (SD, 1.21) T1D | Virtual peer group (VPG) attendees had a significant reduction in HbA1c compared to the standard care group, with a treatment effect of −1.08%. Latinx participants attending VPG sessions showed a larger HbA1c reduction of −2.76% compared to those in standard care. CGM use increased significantly among VPG attendees, from 11% at baseline to 47% by the study’s end, while all other groups showed reduced or stagnant CGM usage. | The study did not follow intent-to-treat principles, analyzing participants by attendance rather than as randomized. Virtual peer group (VPG) sessions led by a youth peer facilitator are not billable, limiting the replicability of this model in other settings. Some patients were excluded, which limits the generalizability of the results. The small sample size also means that a few outliers could significantly influence the mean CES-D score. |

| Bolter, Main and Wiebe. (2022) [36] Southwestern United States of America To examine whether mother and adolescent reports of responsibility diabetes management tasks varied across ethnic groups. To examine whether shared versus individual (i.e., mother or adolescent) responsibility was linked to better diabetes health outcomes (lower HbA1c, higher self-management behaviors, and fewer depressive symptoms) among Latinx and non-Latinx White families. To test if ethnicity moderated the association between the division of diabetes responsibility and diabetes health outcomes. | Cross-sectional study 56 Latinx mother-adolescent dyads (47.5%) Mean age: 13.24 years (SD, 1.69) T1D | Latina mothers reported more shared and less adolescent responsibility than non-Latinx White mothers, but there were no ethnic differences in adolescent reports of responsibility. Independent of demographic and illness-related characteristics, both mother and adolescent reports of shared responsibility were associated with higher self-management behaviors, while individual responsibility (by either the adolescent or mother alone) was generally associated with lower self-management behaviors. Shared responsibility was associated with higher mother-reported self-management behaviors in Latinx families, but not in non-Latinx White families. Shared and individual responsibility were not associated with HbA1c or depressive symptoms. | The study’s cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality between shared responsibility, self-management behaviors, and health outcomes. The reliance on self-reported data from both mothers and adolescents may introduce bias due to discrepancies between their perceptions. Additionally, the study primarily focused on mother-adolescent dyads, with limited data on fathers’ involvement in diabetes management, despite evidence suggesting that fathers may play a unique role in some families. |

| Bortsov et al. (2011) [37] Ohio, Colorado, Washington, South Carolina, Hawaii, and California, United States of America To explore demographic, socioeconomic, diabetes-related, and behavioral correlates of dietary intake of dairy, fruit, vegetables, sweetened soda, fiber, calcium, and saturated fat in youth with diabetes. | Cross-sectional study 324 Latino participants (11.5% T1D, 20% T2D) Mean age: 15.6 years (range, 10–22) T1D, T2D | Hispanic youth had significantly higher fiber intake compared to White non-Hispanic (WNH) youth. Soda consumption among Hispanic youth was lower than that among WNH youth. Calcium intake was also higher among Hispanic participants than WNH youth. | The cross-sectional design limits causal inferences between correlates and dietary intake. The use of food frequency questionnaires may lead to an underestimation of actual food intake. Additionally, the sample may not be representative, as groups with low socioeconomic status might be underrepresented, which could affect the generalizability of the findings. |

| Brodar et al. (2021) [38] Florida, United States of America To assess the feasibility and effectiveness of implementing a comprehensive psychosocial screening program in a pediatric diabetes clinic. | Cross-sectional study 136 Latino participants (58.5%) Mean age: 14.82 years (SD, 1.90) T1D | Over 75% of adolescents with T1D screened positive for at least one psychosocial concern. Common issues included low motivation to manage diabetes (52%), insulin non-adherence (36%), mild depressive symptoms (21%), diabetes stress (22%), and anxiety (18%). Psychosocial concerns were significantly associated with clinical outcomes: higher A1c and insulin non-adherence were linked to increased depressive symptoms, anxiety, disordered eating, diabetes stress, family conflict, and blood glucose monitoring stress. Adolescents with worse glycemic control (A1c > 9%) were more likely to have multiple psychosocial concerns, including a higher suicide risk and disordered eating behaviors. Insulin non-adherence, disordered eating, diabetes stress, and family conflict predicted higher A1c. The screening program led to a 25% increase in referrals to the psychology team, suggesting that routine screening helps identify adolescents needing psychological support. | The cross-sectional design limits causal conclusions. The reliance on self-reported data from adolescents may introduce bias and may not fully capture their psychosocial functioning. The absence of parental reports limits the comprehensiveness of the adolescents’ well-being assessment. The exclusion of youth with T2D limits generalizability. The study focused on within-clinic consultations and did not track outcomes for patients referred to external mental health providers. Some measures were modified and unvalidated for this screening program, requiring further validation. |

| Butler et al. (2017) [39] No specific states, United States of America To examine whether race/ethnicity moderates relationships of (a) diabetes stress and general life stressors with (b) diabetes outcomes of glycemic control and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) among emerging adults (aged 18–25 years) with T1D. | Cross-sectional study 357 Latino participants (10%) Mean age: 20.3 years (SD, 2.1) T1D | Hispanic participants had higher HbA1c levels than WNH participants (9.1% vs. 8.4%). Diabetes-specific stress was more strongly associated with higher HbA1c levels among Hispanic participants. In total, 31% of Hispanic participants often or always experienced diabetes-specific stress, compared to 22% of WNH participants. The incidence of DKA was higher in Hispanic participants, with 13% experiencing one or more episodes, compared to WNHs. | It was not possible to examine whether participants with missing HbA1c or DKA data differed from those with complete data. The cross-sectional design prevents us from determining the directionality of the associations. The study did not examine specific general life stressors, and some aspects of diabetes-specific stress were not captured. The use of a one-item measure for general stress is another limitation. |

| Chang et al. (2020) [40] California, United States of America To (1) analyze glycemic trends and associated risk factors to help identify a high-risk cohort for intensive case management and (2) determine the impact of weight reduction and medication regimen on glycemic outcome. | Retrospective, observational study 183 Latino participants (80%) Mean age: 16.9 years (SD, 2.5) T2D | Weight loss in the first year after diagnosis was associated with improved HbA1c levels, with participants who lost weight showing better glycemic control. Participants on metformin monotherapy had a median weight reduction of 2.6%, while those on insulin-containing regimens gained weight. At 5 years post-diagnosis, the mean HbA1c returned to the initial level, indicating poor long-term glycemic control. The odds of having uncontrolled diabetes (HbA1c > 8%) at 5 years increased if the diagnostic HbA1c was >8.5%, with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.41. | The natural history design lacked uniformity in laboratory tests, and there were missed appointments, which may have affected the power of the results. Some participants had missing clinical data, limiting the ability to draw stronger correlations between HbA1c and variables of interest. The study did not measure beta-cell function or account for changes in medication over time, which might have affected glycemic outcomes. |

| Crespo-Ramos, Cumba-Avilés and Quiles-Jiménez. (2018) [41] Ponce City, Puerto Rico To explore the prevalence and nature of diabetes-related stigma (DRS) in Latino youth with T1D, focusing on the relationship between stigma and depressive symptoms, as well as the sources of stigma from peers, family, and healthcare professionals | Cross-sectional study 65 Latino participants (100%) Mean age: 15.05 years (SD = 1.68) T1D | Over two-thirds of adolescents (67.69%) reported experiencing at least one form of diabetes-related stigma, with 49.23% experiencing both social stigma (SS) and internalized stigma (IS). Peers were identified as the main source of social stigma. A significant relationship was found between stigma and depressive symptoms, with adolescents experiencing stigma, particularly social stigma, having higher odds of being diagnosed with depression. Depression scores were correlated with the number of stigma experiences. Social stigma included derogatory names like ‘junkie’ or ‘terrorist’ due to insulin use or the use of pumps, while internalized stigma reflected feelings of being different or inferior. Peers were the most frequent source of stigma, followed by family and healthcare professionals. Adolescents from urban areas and larger families were more likely to report stigma experiences. | Sample bias: All participants had depressive symptoms, which may not represent the broader T1D adolescent population. Geographical limitations: The clinic-based setting may have excluded participants from distant regions of Puerto Rico. Contextual influence: Participants may have perceived researchers as therapists, which could have affected how they reported stigma experiences. Instrument limitations: The data collection tool was not specifically designed for stigma assessment, missing factors such as media influence. |

| Nicholl et al. (2019) [42] No stated specific location from data, United States of America To compare diabetes management trajectories of Hispanic and WNH youth with T1D over the course of late childhood and early adolescence. In addition, the study compared youths’ trajectories on a variety of variables that have been previously shown to impact diabetes management during adolescence (e.g., regimen responsibility, family support, and family conflict). | Longitudinal study 33 Latino participants (13.8%) Mean age: 10.76 years, (SD, 1.06) T1D | At baseline, Hispanic youth had significantly poorer glycemic control, more family conflict, and fewer blood glucose checks on average compared to WNH youth. Similarly to WNH youth, Hispanic youth have increasing independence in regimen tasks and decreasing parent autonomy support during this developmental period. However, while Hispanic youth had worsening diabetes management during early adolescence (as did WNH youth), Hispanic parents reported a more gradual change in youths’ diabetes management over early adolescence. | The focus on Hispanic families in the study treated individuals of different national origins as the same, despite cultural, socioeconomic, and acculturation differences not being assessed. Most Hispanic youth in the sample came from one geographic region, and there are likely important differences among Hispanic subgroups. The small sample size of Hispanic participants in this secondary data analysis limits the study’s confidence and highlights the need for larger, more diverse samples in future longitudinal research. |

| Gallegos-Macias et al. (2003) [43] New Mexico, United States of America To determine whether there is a disparity in glycemic control between Hispanic and WNH children and adolescents with T1D and to identify factors associated with glycemic control in these populations. | Cross-sectional study 84 Latino participants (45.9%) Mean age: 12.2 years (SD, 4.2) T1D | Hispanic youths with T1D had poorer metabolic control than their WNH counterparts. They exhibited lower compliance with home blood sugar monitoring, but their parents reported greater supervision of their diabetes treatment. Hispanic families had significantly lower incomes, health insurance rates, and educational attainment by both fathers and mothers. Lower family socioeconomic status, but not ethnicity or parental educational attainment, was associated with significantly higher HbA1c, regardless of ethnicity. | The study was conducted in a single clinic, potentially limiting generalizability. It did not examine other ethnic groups beyond Hispanics and White non-Hispanics. The use of self-reported data for some socioeconomic variables may introduce bias. |

| Gandhi et al. (2016) [44] Authors from Texas, United States of America To discuss the psychosocial aspects of T1D in Latino and Asian-American youth, with a focus on the challenges they face regarding glycemic control, healthcare access, and culturally appropriate interventions. | Literature review T1D | Latino youth with T1D have poorer glycemic control than WNHs, with 65% showing suboptimal control as they age. Socioeconomic status, healthcare access barriers, language issues, and low health literacy affect diabetes management. Family involvement, particularly familismo, helps adherence but can reduce youth independence in management. Less acculturated families provide stronger support, but more acculturated youth have worse control. Mental health issues, including depression, are more common and worsened by cultural stressors, yet mental health services are underutilized. Latino youth have higher obesity rates, worsened by unhealthy dietary patterns, contributing to complications. Culturally sensitive interventions, like bilingual education and family-centered approaches, show potential but are scarce. | No direct limitations of the review process are mentioned. |

| Gold et al. (2021) [45] Colorado, United States of America To evaluate the cost and healthcare utilization (such as emergency department visits and hospitalizations) associated with a culturally sensitive, shared medical appointment model designed for Latino children with T1D. The study also assessed the cost-effectiveness of the program. | Non-randomized controlled trial 57 Latino participants (100%) Mean age 12.6 years (SD, 3.3) T1D | The intervention group had fewer hospitalizations (2% compared to 12% in the control group) and a trend toward fewer ED visits (19% compared to 32% in the control group) 6–12 months after starting the program. The program led to significant cost savings. The per-patient healthcare cost savings were USD 2710 in the first year, with total per-patient savings of USD 2077 when considering both program and healthcare costs. Over five years, the estimated cost savings were USD 14,106 per patient. | Data on medications, test strips, and diabetes-related technology for controls were missing. Technology data were available for program participants, but not controls, raising concerns about the complete ascertainment of technology use. Information on office visits was missing, with difficulty distinguishing diabetes care from shared medical appointments due to multiple diagnosis codes. The study could not identify potential substitutions of shared appointments for regular visits and did not include office visits in the analysis. Time costs for hospitalization, program participation, and travel were not captured, though these are unlikely to outweigh the cost savings from reduced healthcare utilization. |

| Guerrero-Ramírez and Cumba-Avilés. (2018) [46] San Juan, Puerto Rico To explore the factors associated with suicidal ideation (SI) and diabetes-related quality of life (DRQOL) in adolescents with T1D from Puerto Rico. | Cross-sectional study 51 Latino Participants (100%) Mean age: 14.78 years (range, 12–17) T1D | Factors associated with suicidal ideation (SI) included depressive symptoms, somatic complaints, and perceived family emotional support, explaining 46% of the variance in SI. Depressive symptoms were the strongest predictor of SI. Factors associated with diabetes-related quality of life (DRQOL) included cognitive alterations, barriers to adherence, family emotional support, and self-efficacy, explaining 61% of the variance in DRQOL. A significant association was found between poorer quality of life and inadequate glycemic control (HbA1c ≥ 7.50), but no direct association was observed between HbA1c as a continuous variable and QOL. | The small sample size limited statistical power, and the study was conducted in Puerto Rico, which may limit generalizability to other Latino populations. The cross-sectional design prevented exploration of causal relationships. Additionally, cultural factors and longitudinal outcomes were not considered. |

| Hsin et al. (2010) [47] Florida, United States of America To examine the relationship between family involvement, acculturation, and diabetes management (adherence and glycemic control) among Hispanic youth with T1D | Cross-sectional study 111 Latino Participants (100%) Mean age 13.33 years, (SD, 2.82) T1D | Better adherence to diabetes management was associated with less independent youth responsibility for diabetes tasks, more family support for diabetes care, and recent generational status (fewer generations in the US). Better glycemic control was linked to higher parental education and better adherence. Family support mediated the relationship between youth responsibility and adherence, showing that family involvement positively influenced diabetes management in Hispanic youth. | The study lacked sufficient statistical power to test differences across Hispanic/Latino subgroups. While caregiver measures were translated into Spanish, youth measures were not. Acculturation variables, especially linguistic acculturation, may relate differently to health outcomes in areas with less cultural and language diversity. The sample lacked representation of Mexican-American backgrounds, limiting generalizability. Additionally, parents and youths may have different perspectives on diabetes care. |

| Joiner et al. (2020) [3] Connecticut, United States of America To explore the perceptions and experiences of Latino adolescents with T1D and their parents with limited English proficiency (LEP), focusing on how social and contextual factors, including cultural and linguistic aspects, influence their self-management of T1D. | Qualitative study 24 Latino participants (100%) Mean age: 15.4 years (range, 12–19) T1D | Parents and adolescents initially lacked knowledge and skills for self-management of T1D. Daily tasks, like checking blood glucose and managing insulin, were stressful. T1D interfered with school and social activities. Adolescents desired more independence but felt less autonomous with adult involvement. Family support and spirituality helped in coping, while adolescents found social environments challenging for healthy choices. Traditional family foods were adjusted for T1D, and some parents struggled with balancing culture and diet. Many parents felt isolated, but those with Spanish-speaking healthcare team members felt supported. Parents expressed interest in meeting other Spanish-speaking families for support. | Participants were recruited from a single pediatric subspecialty practice, limiting generalizability. They may not have experienced the full extent of language barriers seen in other settings, which could affect appointment attendance, use of preventive care, and satisfaction. Additionally, the interview guide focused on open-ended narratives, potentially limiting the depth of cultural insights regarding participants’ experiences with T1D. |

| Knight and Perfect. (2019) [48] No stated specific location from data, United States of America To examine how children and adolescents with T1D glucose levels during and prior to academic assessment contributed to performance on reading, writing, and mathematics tasks. | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) 43 Latino participants (51.8%) Mean age: 13.69 years (SD, 2.10) T1D | Hyperglycemia during academic tasks was linked to poorer performance in reading, writing, and math fluency. Youth with glucose levels in the hyperglycemic range performed worse than those in the target range, with levels between 140 mg/dL and 180 mg/dL particularly affecting fluency tasks. Time spent in the hypoglycemic range (below 70 mg/dL) prior to testing was also associated with poorer performance, especially in math and writing. Both short-term glycemic fluctuations and long-term control (HbA1c) significantly impact academic performance in youth with T1D. | The study’s generalizability is limited by its small sample size and recruitment from a single region. Not all participants had complete CGM data. Further research is needed to explore how glucose variability over longer periods affects academic performance and the role of school-based accommodations for students with T1D. |

| Main et al. (2022) [49] California, United States of America To (1) test associations between parents’ empathic accuracy for their adolescents’ positive and negative emotions and adolescents’ physical and mental health (HbA1c, diabetes self-care, and depressive symptoms) in a predominantly Latinx sample of adolescents with T1D and their parents, and (2) explore how familism values were associated with parent empathic accuracy and adolescent physical and mental health in this population. | Cross-sectional study 68 Latino adolescents (81%) Mean age: 12.74 years (SD, 1.74) T1D | Parents’ empathic accuracy regarding their adolescents’ negative emotions was linked to lower HbA1c, better self-care, and fewer depressive symptoms. Adolescents with parents who understood their negative emotions had better diabetes outcomes. However, empathic accuracy for positive emotions was not significantly related to physical or mental health outcomes. Familism values did not significantly affect parents’ empathic accuracy, but adolescents with higher familism values engaged in better diabetes self-care. | The study was cross-sectional, limiting conclusions about causality. The sample size was modest, and while it included a predominantly Latinx population, findings may not generalize to other groups. Additionally, the study did not explore how other aspects of familism might influence empathic accuracy and diabetes management. |

| Main et al. (2014) [50] Southwestern, United States of America To examine associations of parent-adolescent relationship quality (parental acceptance and parent-adolescent conflict) with adolescent T1D management (adherence and metabolic control) and depressive symptoms in Latinos and Caucasians. | Cross-sectional study 56 Latino participants (47.5%) Mean age: 12.74 years (SD, 1.64) T1D | Latino adolescents reported lower levels of parental acceptance and higher diabetes-related conflict compared to Caucasians. Despite more conflict, adherence to diabetes management in Latino adolescents was not strongly affected. Better parental acceptance was linked to improved adherence, while family conflict did not significantly reduce adherence. Glycemic control was poor across both groups. Depressive symptoms were more prevalent in Latino adolescents, and higher family conflict correlated with increased depressive symptoms. Familism likely helped Latino adolescents manage diabetes effectively despite conflict. | The study’s cross-sectional design limits causal inferences. The sample was predominantly Mexican-American, which may not generalize to other Latino groups. Self-reported measures may introduce bias, particularly in reporting adherence and family dynamics. Fathers’ perspectives were not included, and acculturation, which could affect parenting behaviors and family dynamics, was not extensively explored. |

| Mello and Wiebe. (2020) [51] California, United States of America To examine whether disparities in T1D outcomes, specifically in self-management behaviors and HbA1c, exist between Latino and WNH youth, and to assess the role of socioeconomic status (SES) in moderating or explaining these disparities. | Systematic Review The systematic review included a total of 22 studies T1D | Half of the studies showed that Latino youth had poorer glycemic control and self-management, especially in blood glucose monitoring frequency. Socioeconomic status (SES) was a key factor, and when controlled, ethnic differences in T1D outcomes often disappeared. However, in some cases, SES moderated the relationship, with disparities more pronounced at lower SES levels. The review noted inconsistent SES measures across studies, but lower SES was consistently linked to poorer T1D outcomes for Latino youth. | The review noted that findings were inconsistent across studies, particularly regarding the role of SES in explaining or moderating disparities. SES was measured differently across studies, complicating the ability to compare results or identify consistent patterns. Few studies examined socio-cultural factors like acculturation or discrimination, which could contribute to disparities beyond SES. |

| Mello et al. (2017) [52] Southwest, United States of America To examine ethnic differences in diabetes-related stress and coping among Latino and WNH adolescents with T1D and their mothers; to explore mother-adolescent congruence in perceptions of stress and how these variables were associated with diabetes management outcomes, including adherence and glycemic control. | Cross-sectional study 56 Latinx mother-adolescent dyads (47%) Mean age: 13.24 years (SD, 1.69) T1D | Latino adolescents and their mothers reported fewer issues with low blood glucose compared to WNH families. Latina mothers were less likely to report specific diabetes-related stressors. Dyadic stressor congruence was lower among Latino dyads, indicating that Latina mothers may be less aware of what their adolescents find stressful. Latina mothers viewed their adolescents as less competent in coping with diabetes-related stress, although there were no significant differences in coping strategies. Higher congruence in stress perceptions between mothers and adolescents was linked to better glycemic management (lower HbA1c). Latino dyads with lower congruence and lower maternal appraisals of coping competence had poorer diabetes outcomes, including higher HbA1c. | The sample of Latino dyads was relatively small, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other Latino groups. The study also focused only on mothers, without considering paternal involvement. The results are correlational, meaning that causality cannot be inferred. The study did not measure certain culturally relevant variables directly, such as acculturative stress or Latino cultural values like familismo. |

| Pagán-Torres, Cumba-Avilé and Matos-Melo. (2018) [53] Puerto Rico To examine the psychometric properties of Escala de Autoeficacia para la Depresión en Adolescentes (EADA), a scale measuring emotional self-efficacy for depression in Latino youth with T1D. | Cross-sectional study 51 Latino participants (100%) Mean age: 14.78 years (range, 12–17) T1D | The EADA scale showed excellent internal consistency (α = 0.93) and good concurrent validity, with significant correlations between EADA scores and measures of depression, suicidal ideation, and self-efficacy for diabetes management. Higher self-efficacy was associated with better life satisfaction, greater family support, and better diabetes self-care. The interpersonal dimension of self-efficacy was particularly important for Latino adolescents in managing emotions and seeking support from family and friends. | The sample size did not meet the recommended five cases per item for the total scale, though it did for the subscale level. Despite this, the study followed guidelines to establish reliable alpha estimation with small sample sizes. The non-probabilistic nature of the sample is also a limitation. |

| Collazo et al. (2013) [54] Connecticut, United States of America To determine whether the establishment of a Spanish Language Diabetes Clinic (SLDC), staffed by Spanish-speaking clinicians, improved metabolic management (HbA1c levels) in Hispanic youth with T1D, compared to similar patients treated in an English Language Diabetes Clinic (ELDC). | Non-randomized controlled trial 21 Latino participants (100%) Mean age: 10.0 years (SD, 0.7) in the SLDC group and 11.0 years (SD, 0.8) in the ELDC group T1D | The SLDC group showed significant improvements in HbA1c (from 8.4% to 7.9%, a decrease of 0.5%, p = 0.01), while the ELDC group saw a smaller, non-significant change (from 8.6% to 8.4%, a decrease of 0.2%, p = 0.14). At the start, only 23% of SLDC patients had HbA1c levels ≤ 7.5%, compared to 33% in the ELDC. After one year, 48% of SLDC patients achieved HbA1c levels ≤ 7.5%, compared to only 19% in the ELDC (p = 0.01). | The small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings. The study was conducted at a single site and for a short duration of one year. Improvements in HbA1c may have been influenced by other factors. |

| Parker, Lee and Reiboldt. (2013) [55] California, United States of America To investigate the perceptions of youth with diabetes mellitus and their parents/guardians about issues related to eating habits and to identify the relationships between treatment and lifestyle/daily care factors, youth characteristics, and eating habits of youth with DM. | Cross-sectional study 82 Latino participants (65.6%) Mean age: 14.16 years (SD, 2.59) T1D, T2D | Hispanic youth who ate more meals at home showed better eating habits and improved perceptions about healthy eating. Strong parent-child relationships were crucial for promoting healthier eating behaviors, with youth sharing diabetes care with their parents showing better habits than those managing care independently. Hispanic families emphasized the importance of family-centered care, though language barriers sometimes made dietary guidance more challenging. | Small sample size and exclusion of participants who spoke languages other than English or Spanish. The use of non-validated composite scores also weakens the strength of the conclusions. |

| Pascual et al. (2019) [56] Colorado, United States of America To develop and evaluate a culturally sensitive shared medical appointment (SMA) model for Hispanic pediatric T1D patients. | Experimental, longitudinal study 88 Latino participants (100%) Mean age of the younger group (<12 years): 8.4 years (SD, 2.7); mean age of the older group (≥12 years): 14.6 years (SD, 2) T1D | Younger children (under 12 years) showed significant improvements in HbA1c, decreasing from 9.2% to 8.7% over two years. Their use of insulin pumps increased significantly from 19% at baseline to 60% by year 2. For older participants (12 years and above), HbA1c remained stable from 9.8% at baseline to year 1 but increased to 10.4% by year 2. Insulin pump use increased from 10% to 23% over the same period. The program had a 98% satisfaction rate, with participants preferring culturally sensitive SMA visits over routine care. | The study had a small sample size and was conducted at a single site, limiting the generalizability of the findings. There were challenges in teen participation and attrition, with lower completion rates among older participants. Long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness were not assessed within the scope of this study. |

| Piven and Duran. (2014) [57] Texas, United States of America To determine whether an occupation-based intervention could improve diabetes self-management skills in a Mexican-American adolescent with T2D who was exhibiting non-adherent behaviors. | Case study 1 Latino participant (100%) 19 years T2D | The intervention led to improved diabetes self-management. This person adhered to a meal plan, lost 5 pounds, and increased his physical activity from 1 to 7 h per week. He began performing daily glucose checks, achieving an average blood glucose of 145 mg/dL, corresponding to an estimated A1c of 6.6%. The youth became more responsible for his diabetes care, with significant improvements in his self-efficacy (from a score of 1 to 7 on the Diabetes Self-Efficacy Scale) and in his satisfaction with his performance on diabetes-related tasks. | The study involved only one participant, so the findings cannot be generalized. There was no withdrawal phase to assess whether the behavioral changes were maintained over time. The subject initially exhibited denial about his diabetes, which may have influenced the accuracy of early self-reports. |

| Pyatak et al. (2017) [58] California, United States of America To assess the efficacy of a manualized occupational therapy (OT) intervention, known as REAL Diabetes, designed to improve glycemic management and psychosocial well-being among low-socioeconomic-status (SES), ethnically diverse young adults with T1D or T2D. | Randomized controlled trial (RCT) 63 Latino participants (78%) Mean age: 22.6 years (SD, 3.5) T1D, T2D | Participants in the intervention group (IG) showed significant improvements in HbA1c (a decrease of 0.57%) compared to the control group (CG), which showed an increase of 0.36%. Quality of life (QOL) improved significantly in the IG, with a 0.7-point increase, compared to a 0.15-point improvement in the CG. Habit strength for checking blood glucose increased by 3.9 points in the IG, compared to 1.7 points in the CG. No statistically significant differences were found for other secondary outcomes, although the IG showed trends of improvement in diabetes distress, life satisfaction, and medication adherence. | The study had a relatively small sample size and lacked the statistical power to fully explore secondary outcomes or the effect of intervention dose. There was no long-term follow-up, so it is unclear if the benefits were sustained over time. The study was conducted in a specific urban setting with a high percentage of Latinx participants, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. |

| Ravi et al. (2021) [59] Colorado, United States of America To assess the uptake rate and clinical impact of CGM on pediatric Medicaid patients with T1D, particularly focusing on glycemic management (HbA1c) after CGM adoption. | Retrospective chart review 264 Latino participants (36.9%) Mean age of participants with some CGM exposure: 10.7 years (SD, 4.5); mean age without CGM exposure: 13.1 years (SD, 4.26) T1D | Hispanic participants were 66.5% less likely to achieve more than 85% CGM usage compared to WNH participants. CGM use was associated with lower A1c levels: Hispanic participants using CGM showed better glycemic management (A1c 8.5%) compared to those who did not use CGM (A1c 9.3%). Although CGM use among Hispanic participants was lower (22.6%), those who did use CGM demonstrated improvements in time in range (TIR) and reduced time in hyperglycemia. | The study had a small number of Hispanic participants using CGM compared to other ethnic groups. Factors such as cultural barriers or prescribing bias may have influenced the lower CGM adoption rate among Hispanic participants. |

| Raymond et al. (2020) [60] California, United States of America To adapt the CoYoT1 Clinic telehealth group appointment model to a low-SES, publicly insured, racially/ethnically diverse young adult population with T1D. | Randomized controlled trial (RCT) 52 Latino participants (53.1%) Mean age: 19.0 years (SD, 1.7) T1D | Participants in the CoYoT1 telehealth group showed improved clinic attendance, with better adherence to care schedules compared to the control group. Psychosocial outcomes, including reduced diabetes distress and improved self-management behaviors, were also noted. Participants were more satisfied with the flexibility offered by telehealth. However, overall HbA1c levels did not significantly improve over the study period. | No direct limitations are mentioned. |

| Reitblat et al. (2016) [61] Connecticut, United States of America To describe the experiences of Hispanic adolescents with T1D from both the adolescents’ and their clinicians’ perspectives. Additionally, the study sought to explore how cultural factors, daily management, and clinician-patient interactions influence the life of Hispanic adolescents with T1D. | Qualitative Study 9 Latino participants (100%) Mean age 13.7 years (SD, 1.6) T1D | The study identified key cultural aspects influencing diabetes management, such as traditional Hispanic foods (often carbohydrate-rich) and family closeness, which was both a protective factor and a potential barrier. Adolescents did not see language as a barrier, even when translating for their parents during clinic visits, though clinicians viewed it as a challenge. Adolescents reported that balancing food, insulin, and exercise was a daily struggle and expressed the tension between managing diabetes perfectly and wanting to live without the constraints imposed by diabetes. | The study was limited by its small sample size and potential selection bias, as older adolescents were harder to recruit. Additionally, participants all came from two-parent households, and there was no representation from single-parent homes, which might have offered different perspectives. |

| Sheikh et al. (2018) [62] Texas, United States of America To assess the rates of diabetes device use (insulin pump and CGM) and their association with glycemic management among youth with T1D in a large, diverse pediatric population. | Cross-sectional study 484 Latino participants (24.3%) Mean age: 13.8 years (SD, 4.2) T1D | Hispanic participants had significantly lower rates of device use (insulin pump and CGM) compared to WNHs. The odds of not using a pump were 1.82 times higher for Hispanic participants compared to WNHs. Similarly, the odds of not using a CGM were 1.62 times higher for Hispanics. CGM use was associated with lower HbA1c for all groups, including Hispanics | The study was limited by its cross-sectional design, which does not establish causality. Additionally, the analysis did not include variables like parental income or education, which are important factors influencing device use |

| George et al. (2016) [63] No stated specific location from the data; United States of America To assess access to and interest in smartphone technology for managing T1D in primarily Hispanic adolescents and their parents. | Cross-sectional study 37 Latino participants (74%) Mean age: 13.6 years (SD, 2.0) T1D | In total, 98% of adolescents had access to the Internet, and 86% had their own smartphones, while 37% reported using smartphone apps to manage their diabetes, with carbohydrate counting being the most common function (88%). Hispanic adolescents showed moderate to high interest in using technology for T1D management, with girls showing more interest than boys in apps for insulin dose calculation and tracking. Parents demonstrated a higher interest in smartphone apps than adolescents, particularly for glucose tracking, carbohydrate counting, insulin dose calculation, and receiving diabetes-related reminders. | The study only included adolescents attending regular clinic visits, which may not represent those with irregular care access. |

| Streisand et al. (2002) [64] Puerto Rico To examine self-care behaviors among children and adolescents with T1D living in Puerto Rico, to determine the relationship between self-care and demographic variables, and to investigate the utility of the 24 h recall interview within a Hispanic population. | Cross-sectional study 41 Latino participants and their mothers (100%) Mean age of the children: 12.6 years (SD = 2.9) T1D | Children in Puerto Rico reported relatively good self-care behaviors despite challenging economic conditions. They averaged 5.5 meals per day, with 52% of calories from carbohydrates and 29% from fat, within the recommended ranges. On average, they exercised once per day for 18 min and conducted two blood glucose tests daily. Older children ate less frequently, and girls were more consistent with insulin administration and nutrition habits compared to boys. | The study was limited by its small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Limited access to medical records reduced available data on metabolic management for some participants. Additionally, the lack of detailed socioeconomic and psychosocial variables hindered a deeper understanding of self-care behaviors. |

| Sullivan-Bolya. (2009) [65] Author from Massachusetts, United States of America To improve the cultural and linguistic sensitivity of an established parent-mentor training curriculum for Latino parents of young children newly diagnosed with T1D. | Descriptive, Participatory Action Research Study 4 Latino mothers and 5 children (100%) Age of mothers: range, 38–42 years; age of children range, 7–12 years T1D | The study found that Latino parents face challenges such as language barriers, lack of access to bilingual health providers, and difficulties finding qualified caregivers or school staff for diabetes management. Mothers emphasized the need for culturally sensitive resources, such as bilingual educational materials, and suggested creating diabetes-friendly versions of traditional Latino meals. The adapted intervention, renamed Familias Apoyadas, was well received and considered culturally relevant. | The study had a small sample size of only four mothers, and all were of Puerto Rican origin, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, all participants were well educated and acculturated, which may not reflect the broader Latino population. |

| Taylor et al. (2016) [66] Southeastern, United States of America To assess whether satisfaction with the healthcare provider is related to regimen adherence among primarily minority youth with T1D. | Cross-sectional study 118 Latino participants (70%) Mean age: 13.88 years (SD, 2) T1D | The study found that greater satisfaction with the healthcare provider, particularly in communication and rapport, was associated with better regimen adherence among youth. This association was stronger for girls than boys. Youth satisfaction with the provider was more closely linked to adherence than parent satisfaction, highlighting the importance of the youth-provider relationship. No significant differences in satisfaction or adherence were found based on ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic). The study emphasizes the importance of improving patient-provider relationships to enhance adherence among minority youth. | Results regarding gender were mixed and should be interpreted with caution due to the lack of an interaction effect. Replication with a larger sample is needed, as no causality can be inferred. The study relied on self-reports, and comparing with objective measures of adherence and provider satisfaction could improve understanding. There was no relationship between HbA1c and self-reported adherence. The semi-structured interview format may have led to inflated adherence reports, with social desirability bias possibly affecting gender findings. |

| Tsai et al. (2022) [67] California, United States of America To assess adolescent and young adult patient attitudes toward, and barriers to, diabetes-specific technology in a predominantly minority, low-socioeconomic-status population, and to investigate whether these differ from those of non-minority youth. | Cross-sectional study 97 Latino participants (56%) Mean age for Latinx English speakers: 17.62 years (SD, 2.78); mean age for Latinx Spanish speakers 14.21 years (SD, 1.91) T1D | Latinx English-speaking participants had more negative attitudes toward both general and diabetes-specific technology compared to Latinx Spanish speakers and non-Latinx English speakers. CGM use was lower in Latinx English speakers (33%) compared to non-Latinx English speakers (61%) and Latinx Spanish speakers (62%). Barriers to technology use were similar across groups, but Latinx English speakers expressed more nervousness about using diabetes devices. Participants with higher HbA1c levels tended to have more negative attitudes toward technology, with Latinx English speakers having the highest HbA1c (9.69%). | The study’s cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality. The study was conducted in a single hospital setting, and the findings may not generalize to other regions. The sample size for certain subgroups (e.g., Latinx Spanish speakers) was relatively small. The questionnaires used to assess attitudes and barriers were adapted from adult surveys, and may not fully capture pediatric experiences. |