A Comparative Study on Pain Perception in Children, After Application of Pre-Cooled and Plain Topical Anaesthetic Gel During Local Anaesthetic Administration—A Parallel Three-Arm Randomised Control Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

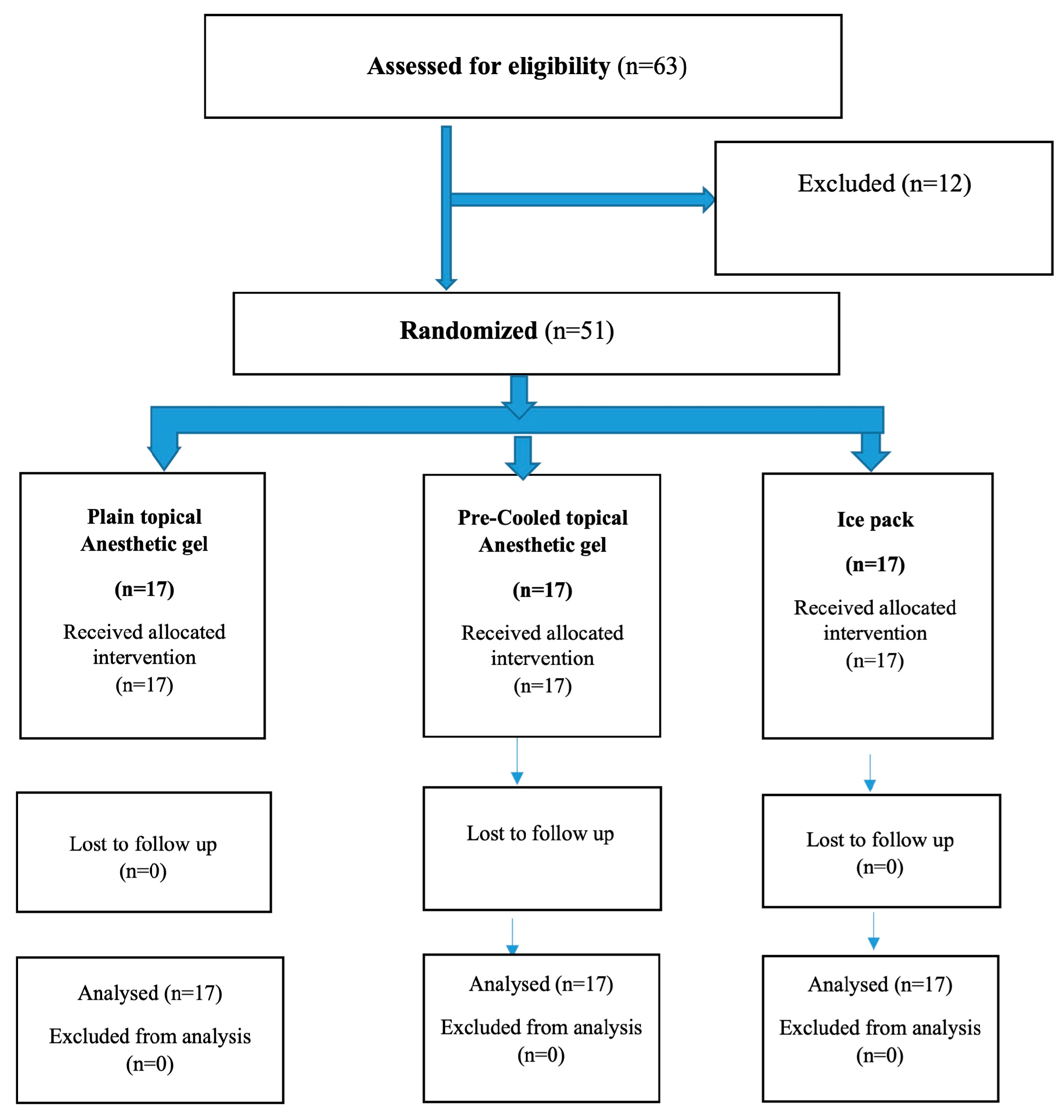

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Ethical Clearance and Informed Consent

2.2. Sample Size Estimation

2.3. Participant Selection

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Sample

2.5. Randomisation and Allocation Concealment

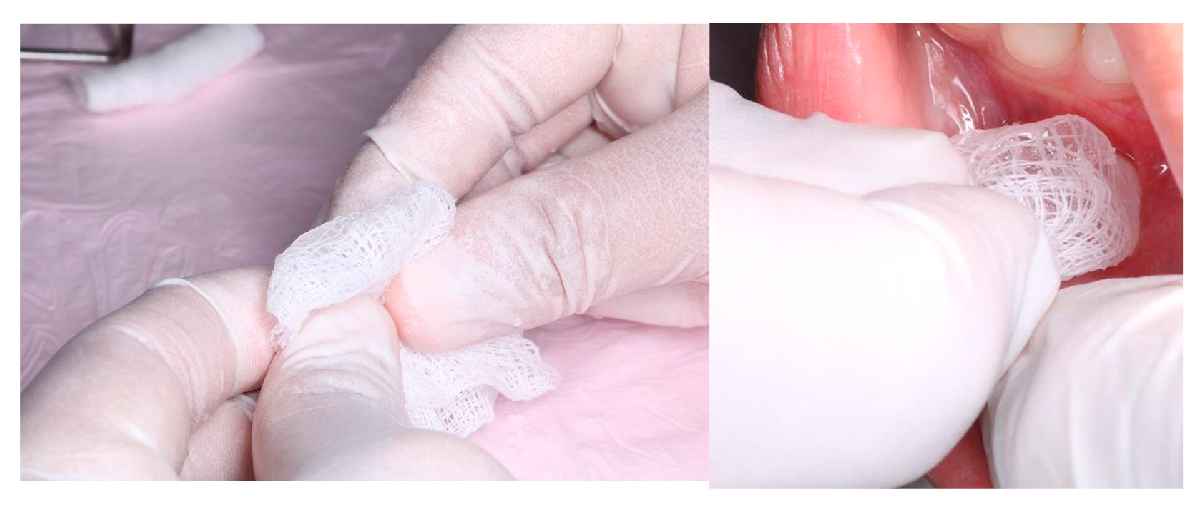

2.6. Procedure

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Outcomes

2.8.1. Primary Outcomes

- Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) Scale

- 2.

- Wong–Baker Scale

2.8.2. Secondary Outcome

- Local anaesthetic administration time:

- 2.

- Frankl Behaviour Rating Scale

- 3.

- Pulse rate

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FLACC | Face, Leg, Activity, Cry, Consolability |

| WBS | Wong–Baker Scale |

| FBRS | Frankel Behaviour Rating Scale |

| LA | Local Anaesthesia |

| CONSORT | Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials |

| SNOSE | Sequentially Numbered, Opaque, Sealed Envelopes |

References

- Remi, R.V.; Anantharaj, A.; Praveen, P.; Prathibha, R.S.; Sudhir, R. Advances in pediatric dentistry: New approaches to pain control and anxiety reduction in children–A narrative review. J. Dent. Anaesth. Pain Med. 2023, 23, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virdikar, S.S.; Prabhakar, A.R.; Basappa, N. A comparative study on pain perception in children, after application of pre cooled and plain topical anesthetic gel during needle insertion for local anesthetic administration-In-vivo trial. J. Updates Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 1, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgione, A.G.; Clark, R.E. Comments on an empirical study of the causes of dental fears. J. Dent. Res. 1974, 53, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabed, A.M.; Alqahtani, F.A.; Hamad Aldosariy, N.M.; Ali Alshamrani, A.S.; Yahya Mahnashi, B.A.; Alshehri, M.M.; Alhassan, S.A.; Almutairi, A.M. Common Challenges in Pediatric Dentistry and the Community’s Role in Overcoming Them. J. Int. Crisis Risk Commun. Res. 2024, 7, 869–875. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Pain management in infants, children, adolescents, and individuals with special health care needs. In The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry; American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry: Chicago, IL, USA, 2024; pp. 435–443. [Google Scholar]

- Aminah, M.; Nagar, P.; Singh, P.; Bharti, M. Comparison of topical anesthetic gel, pre-cooling, vibration and buffered local anaesthesia on the pain perception of pediatric patients during the administration of local anaesthesia in routine dental procedures. Int. J. Contemp. Med. Res. 2017, 4, 400–403. [Google Scholar]

- Bhadauria, U.S.; Dasar, P.L.; Sandesh, N.; Mishra, P.; Godha, S. Effect of injection site pre-cooling on pain perception in patients attending a dental camp at Life Line Express: A split mouth interventional study. Clujul Med. 2017, 90, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenti, C.; Pagano, S.; Bozza, S.; Ciurnella, E.; Lomurno, G.; Capobianco, B.; Coniglio, M.; Cianetti, S.; Marinucci, L. Use of the Er: YAG laser in conservative dentistry: Evaluation of the microbial population in carious lesions. Materials 2021, 14, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, Z.; Polyvios, C. Alternative practices of achieving anaesthesia for dental procedures: A review. J. Dent. Anaesth. Pain Med. 2018, 18, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nat, K.S.; Khanal, D.; Waraich, G.S. Effect of cooled topical anesthetic gel on pain perception during administration of local anaesthesia: A clinical trial. SVOA Dent. 2023, 1, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, N.N.; Sargod, S.S.; Bhat, S.S.; Hegde, S.K.; Bava, M.M. Effectiveness of precooling the injection site using tetrafluorethane on pain perception in children. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2018, 36, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Jaisani, M.R.; Dongol, A.; Acharya, P.; Yadav, A.K. Effectiveness of pre-injection use of cryoanaesthesia as compared to topical anesthetic gel in reducing pain perception during palatal injections: A randomized controlled trial. J. Dent. Anaesth. Pain Med. 2024, 24, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaderi, F.; Banakar, S.; Rostami, S. Effect of pre-cooling injection site on pain perception in pediatric dentistry: “A randomized clinical trial”. Dent. Res. J. 2013, 10, 790–794. [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaj, A.; Sabu, J.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Jagdeesh, R.B.; Praveen, P.; Shankarappa, P.R. A comparative evaluation of pain perception following topical application of benzocaine gel, clove-papaya based anesthetic gel and precooling of the injection site before intraoral injections in children. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2020, 38, 184–189. [Google Scholar]

- Tirupathi, S.P.; Rajasekhar, S. Effect of precooling on pain during local anaesthesia administration in children: A systematic review. J. Dent. Anaesth. Pain Med. 2020, 20, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, V.; Hameed, A.; Sheikh, H.A. Comparison of Three Different Techniques to Allay Anxiety before Local Anaesthesia Injection in Pediatric Population. Dent. Res. Manag. 2019, 3, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurucharan, I.; Sekar, M.; Balasubramanian, S.; Narasimhan, S. Effect of precooling injection site and cold anesthetic administration on injection pain, onset, and anesthetic efficacy in maxillary molars with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 1855–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Rashid, S.; Shaikh, A.B.; Ali, M.; Hosein, T.; Askary, S.H. Effect of pre-cooling the injection site on pain perception in paediatric dentistry. Pak. Armed Forces Med. J. 2021, 71, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, S.I.; Voepel-Lewis, T.; Shayevitz, J.R.; Malviya, S. The FLACC: A behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatr. Nurs. 1997, 23, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Garra, G.; Singer, A.J.; Domingo, A.; Thode, H.C., Jr. The Wong-Baker pain FACES scale measures pain, not fear. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2013, 29, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, V.K.; Samuel, S.R. Appropriateness of various behavior rating scales used in pediatric dentistry: A Review. J Glob. Oral Health 2019, 2, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, K.S.; Joshi, S.; Pawar, S.; Lohokare, A.U.; Rathod, P.B. Evaluation of the Effect of Distant Cold Stimulation on Pain During Palatal Injection: A Randomized Split-Mouth Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e37749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, L.; Ravindran, V. Efficacy of Cryotherapy Application on the Pain Perception during Intraoral Injection: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 14, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.; Garg, N.; Pathivada, L.; Yeluri, R. Cooling the soft tissue and its effect on perception of pain during infiltration and block anaesthesia in children undergoing dental procedures: A comparative study. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2019, 13, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achmad, M.H.; Horax, S.; Rizki, S.S.; Ramadhany, S.; Singgih, M.F.; Handayani, H.; Sugiharto, S. Pulse rate change after childhood anxiety management with modeling and reinforcement technique of children’s dental care. Pesqui. Bras. Em Odontopediatria E Clínica Integr. 2019, 19, e4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilakamuri, S.; Svsg, N.; Nuvvula, S. The effect of pre-cooling versus topical anaesthesia on pain perception during palatal injections in children aged 7–9 years: A randomized split-mouth crossover clinical trial. J. Dent. Anaesth. Pain Med. 2020, 20, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindova, M.P.; Belcheva, A.B. Behaviour Evaluation Scales for Pediatric Dental Patients–Review and Clinical Experience. Folia Medica 2014, 56, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, N.; Mathur, S.; Malik, M. Effectiveness of cryotherapy, sucrose solution and a combination therapy for pain control during local anaesthesia in children: A split mouth study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 46, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Danu Dayakar, P.S.; Balachandran, D. Comparison of pain perception between two pre-injection techniques; pre-cooling over topical anaesthetic application during infiltration anaesthesia in children. Guident 2023, 16, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Mohiuddin, I.; Setty, J.V.; Srinivasan, I.; Desai, J.A. Topical application of local anaesthetic gel vs ice in pediatric patients for infiltration anaesthesia. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2015, 4, 12934–12940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahshidfar, B.; Cheraghi Shevi, S.; Abbasi, M.; Kasnavieh, M.H.; Rezai, M.; Zavereh, M.; Mosaddegh, R. Ice Reduces Needle-Stick Pain Associated With Local Anesthetic Injection. Anesthesiol. Pain Med. 2016, 6, e38293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SI. No | Parameters | Plain Topical Anaesthetic Gel N (%) | Pre-Cooled Topical Anaesthetic Gel N (%) | Ice Pack Application for a Period of 1 Min at the Injection Site N (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 10 (58.8) | 1 | ||

| 6–9 years | 10 (58.8) | 10 (58.8) | |||

| 10–12 years | 07 (41.1) | 07 (41.1) | 07 (41.1) | ||

| 2 | Gender | 11 (64.7) | 11 (64.7) | 11 (64.7) | |

| Male | |||||

| Female | 06 (35.3) | 06 (35.3) | 06 (35.3) | 1 |

| SI. No | Parameters | Plain Topical Anaesthetic Gel (Mean ± SD) | Pre-Cooled Topical Anaesthetic Gel (Mean ± SD) | Ice Pack Application for a Period of 1 Min at the Injection Site (Mean ± SD) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Time required for administration of LA in seconds | 40.23 ± 12.10 | 42.40 ± 6.02 | 43.29 ± 5.19 | 0.551 |

| 2 | Pulse rate Before anaesthesia | 91.31 ± 10.80 | 96.14 ± 10.20 | 88.76 ± 9.21 | 0.202 |

| During topical anaesthesia | 93.58 ± 12.28 | 95.76 ± 9.23 | 87.47 ± 16.89 | 0.175 | |

| During anaesthesia | 97.23 ± 10.98 | 97.80 ± 8.80 | 93.29 ± 12.50 | 0.420 | |

| 1 min after LA administration | 91.70 ± 12.41 | 93.23 ± 8.70 | 89.58 ± 10.45 | 0.607 |

| SI. No | Parameters | Plain Topical Anaesthetic Gel [Median (Q1, Q3)] | Pre-Cooled Topical Anaesthetic Gel [Median (Q1, Q3)] | Ice Pack Application for a Period of 1 Min at the Injection Site [Median (Q1, Q3)] | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FBRS Before anaesthesia | 4 (3, 4) | 4 (3, 4) | 4 (4, 4) | 0.546 |

| During anaesthesia | 2 (2, 4) | 3 (3, 3) | 2 (2, 4) | <0.001 *** | |

| After anaesthesia | 3 (3, 4) | 3 (3, 4) | 3 (3, 4) | 0.781 | |

| 2 | FLACC Scale during topical anaesthesia | 0 (0, 0) | 1 (0, 2) | 3 (3, 3) | <0.001 *** |

| 3 | FLACC Scale during LA | 3 (2, 3) | 1 (0, 1) | 4 (4, 5) | <0.001 *** |

| 4 | WBS Immediately after topical anaesthesia | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 2) | <0.001 *** |

| Immediately after injection | 4 (4, 6) | 2 (0, 2) | 6 (4, 8) | <0.001 *** | |

| Before the procedure | 2 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 0) | 2 (0, 2) | 0.0531 | |

| During the treatment | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 2) | 0.0605 | |

| At the end of the treatment | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.01 ** |

| FBRS | Before, During and After Anaesthesia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | Group II | Group III | ||

| Friedmann test value | 15.08 | 16.47 | 12.09 | |

| p value | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.002 * | |

| 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | Before | (3.39, 3.90) | (3.54, 3.99) | (3.33, 3.84) |

| During | (2.23, 3.18) | (2.10, 3.19) | (2.81, 3.42) | |

| After | (2.68, 3.66) | (3.16, 3.67) | (3.21, 3.73) | |

| Effect size | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.13 | |

| Pair Wise Comparison- Post Hoc FBRS | Group I | Group II | Group III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Statistic | Adj. Sig. p Value | Test Statistic | Adj. Sig. p Value | Test Statistic | Adj. Sig. p Value | |

| During anaesthesia vs. After anaesthesia | −0.50 | 0.43 | −0.62 | 0.22 | −0.64 | 0.178 |

| During anaesthesia vs. Before anaesthesia | 0.645 | 0.18 | 0.97 | 0.01 * | 1.03 | 0.01 * |

| After anaesthesia vs. Before anaesthesia | 0.145 | 1.00 | 0.35 | 0.91 | 0.38 | 0.79 |

| WBS | Immediate After Topical, Injection, Before, During and at the End | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | Group II | Group III | ||

| Friedmann test value | 41.82 | 30.93 | 47.85 | |

| p value | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | |

| 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | Immediate | (0.41, 1.47) | (0.02, 0.92) | (0.00, 0.00) |

| After the injection | (4.65, 7.11) | (0.89, 2.39) | (3.29, 5.65) | |

| Before | (0.67, 1.92) | (−0.11, 1.05) | (0.62, 2.21) | |

| During | (0.08, 1.33) | (0.00, 0.00) | (−0.05, 0.76) | |

| At the end | (0.02, 0.92) | (0.00, 0.00) | (0.00, 0.00) | |

| Effect size | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.65 | |

| Pair Wise Comparison- Post Hoc WBS | Group I | Group II | Group III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Statistic | Adj. Sig. p Value | Test Statistic | Adj. Sig. p Value | Test Statistic | Adj. Sig. p Value | |

| Immediately after topical anaesthesia vs. At the end of the treatment | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.18 | 1.00 |

| Immediately after topical anaesthesia vs. During the treatment | 0.50 | 1.00 | −0.35 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 1.00 |

| Immediately after topical anaesthesia vs. Before the procedure | 1.70 | 0.02 | −1.12 | 0.39 | 0.79 | 1.00 |

| Immediately after topical anaesthesia vs. Immediately after injection | 1.70 | 0.02 | −2.50 | 0.001 * | 2.56 | 0.001 * |

| At the end of the treatment- vs. During the treatment | 0.44 | 1.00 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.26 | 1.00 |

| At the end of the treatment- vs. Before the procedure | 0.44 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 1.00 |

| At the end of the treatment vs. Immediately after injection | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.50 | 0.001 * | 2.38 | 0.001 * |

| During the treatment vs. Before the procedure | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.77 | 1.00 | −0.35 | 1.00 |

| During the treatment-WBS-Immediately after injection | 1.26 | 0.20 | 2.15 | 0.001 * | −2.12 | 0.001 * |

| Before the procedure vs. Immediately after injection | −1.21 | 0.26 | 1.38 | 0.11 | 1.76 | 0.01 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maganur, P.C.; Ghawi, A.A.; Arishi, G.D.; Bahammam, H.A.; Alessa, N.; Hamed, N.E.; Jawhali, N.A.; Sawady, M.; Manqari, A.I.H.; Vishwanathaiah, S. A Comparative Study on Pain Perception in Children, After Application of Pre-Cooled and Plain Topical Anaesthetic Gel During Local Anaesthetic Administration—A Parallel Three-Arm Randomised Control Trial. Children 2025, 12, 863. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070863

Maganur PC, Ghawi AA, Arishi GD, Bahammam HA, Alessa N, Hamed NE, Jawhali NA, Sawady M, Manqari AIH, Vishwanathaiah S. A Comparative Study on Pain Perception in Children, After Application of Pre-Cooled and Plain Topical Anaesthetic Gel During Local Anaesthetic Administration—A Parallel Three-Arm Randomised Control Trial. Children. 2025; 12(7):863. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070863

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaganur, Prabhadevi C., Atiah Abdulrahman Ghawi, Ghadi DuhDuh Arishi, Hammam Ahmed Bahammam, Noura Alessa, Nebras Essam Hamed, Nada Ali Jawhali, Mohammed Sawady, Asim Ibrahim H. Manqari, and Satish Vishwanathaiah. 2025. "A Comparative Study on Pain Perception in Children, After Application of Pre-Cooled and Plain Topical Anaesthetic Gel During Local Anaesthetic Administration—A Parallel Three-Arm Randomised Control Trial" Children 12, no. 7: 863. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070863

APA StyleMaganur, P. C., Ghawi, A. A., Arishi, G. D., Bahammam, H. A., Alessa, N., Hamed, N. E., Jawhali, N. A., Sawady, M., Manqari, A. I. H., & Vishwanathaiah, S. (2025). A Comparative Study on Pain Perception in Children, After Application of Pre-Cooled and Plain Topical Anaesthetic Gel During Local Anaesthetic Administration—A Parallel Three-Arm Randomised Control Trial. Children, 12(7), 863. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070863