The Role of Caregivers in Supporting Personal Recovery in Youth with Mental Health Concerns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design Overview

2.2. Recruitment and Participants

2.3. Participants

| Caregiver | Age | Gender | Time in MH | Location | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46 | Female | 9 yearrs | Metro | Post-Graduate |

| 2 | 49 | Female | 2 years | Rural | Year 12 |

| 3 | 40 | Female | 4 years | Regional | Diploma |

| 4 | 53 | Female | 4 years | Metro | Bach Degree |

| 5 | 44 | Female | 4 years | Metro | Bach Degree |

| 6 | 45 | Female | 2.5 years | Metro | Certificate111 |

| 7 | 50 | Female | 7.5 years | Metro | Year 11 |

| 8 | 44 | Female | 5 years | Rural | Assoc Dip |

| 9 | 42 | Female | 2 years | Regional | Bach Degree |

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Providing Unconditional Love and Positive Regard

“The general sense from everyone I speak to is that their normal network of friends and family is difficult to talk to because they don’t get it. [...] But it’s not because they’re not getting the complexity [...] it is an illness you know their thinking is behavioural.”

“It makes you sort of question your parenting, and in some ways, it changes how you think people perceive you as a parent, too.”

“Being a little lighthouse […], you know, shining the light for her.”

“Building her self-confidence through compliments and through other ways about understanding her perception of self as well.”

3.2. Theme 2: Encouraging Connection with Peers

“I have to pretty much instigate any catchups with his peers. He never instigates anything […]. I think sometimes he wants to connect but doesn’t know how to”.(Caregiver 4)

“She didn’t want to connect […] she was pretty resistant to connecting. She wanted to know that she hadn’t been forgotten.”

“Well, I think he feels like he is an outsider, and he is different to his peers. He feels like he connects more to adults than his peer group. For him, it’s been difficult to make connections because of his lack of trust and his level of anxiety in social settings, and it’s also been difficult for him to branch out away from me […] because he didn’t want to separate from me.”

3.3. Theme 3: Co-Creating a Sense of Purpose, Meaning and Hope

“I think he probably needs to know that he has a purpose. That there’s a purpose to being alive and for that to be part of the therapy goal”.(Caregiver 4)

“Having an idea about what his future or some of it looks like. Actually, having some future goals.”

“That she’s gained a load of self-worth and feeling good about herself and happiness with what she’s doing in her life. Purpose, and a bit of direction”.(Caregiver 1)

“Gaining control back ... just re-establishing routine and helping him to know that he can do it. Like that sense of accomplishment and knowing that he’s supported by a small community, and everyone’s connected.”

3.4. Theme 4: Supporting Assertiveness and Advocacy

“It’s really sort of about helping them to build the skills that they need to manage those sorts of situations that can pop up.”

“Being involved in their treatment is such a good thing, you know. Basically, they’re adults, aren’t they? So, for her to have that sense that she is to a degree in charge of her own recovery is a great thing”.(Caregiver 2)

“Sometimes it’s just like knowing what’s adolescent behaviour, and what may be a sign of something not being quite right.”

“Teaching her that her psychologist is her safe space. So, [youth] goes into all of those sessions by herself. That’s her space. That’s her space to share and have really good discussions, to speak up for herself”.(Caregiver 9)

“I’m not going to hold you with me. You have got to do this on your own. You have to manage your illness; you have to manage your own. This is your journey, not my journey […] it’s your choice”.(Caregiver 6)

“Parents [need] to have that basic mental health training. Because sometimes I think to myself, when (young person) asks me stuff, I don’t know if I’m actually making the situation worse or better because I don’t know if I’m responding correctly.”

3.5. Theme 5: Promoting Strength and Opportunities for Mastery

“Celebrating the things that she hasn’t been able to do before, and I say to her, you need to celebrate those little achievements that you made. Celebrating how well she is doing, you know, which is what you and I would do as a normal thing. She needs to acknowledge how well she has done so for her to have that sense that she is, to a degree, in charge of her own recovery is a great thing”.(Caregiver 2)

“Being told that she is a strong, resilient young person who can do this thing. […]. Also being really honest and saying, but it’s not going to be comfortable. In fact, I had a conversation with her; she failed her driving test on Monday; it was just all over the place. We had this really good conversation where I said, look, you know, disappointment sucks, hurts, really hurts. But you’ll get through it, and you learn from it”.(Caregiver 3)

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Burns, J.M.; Birrell, E.; Bismark, M.; Pirkis, J.; Davenport, T.; Hickie, I.; Weinberg, M.; Ellis, L. The Role of Technology in Australian Youth Mental Health Reform. Aust. Health Rev. 2016, 40, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grist, R.; Croker, A.; Denne, M.; Stallard, P. Technology Delivered Interventions for Depression and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.Q.; de Geus, H.; Roest, S.; Payne, L.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Littlewood, R.; Hoyland, M.; Stathis, S.; Bor, W.; Middeldorp, C.M. Characteristics and Treatment Outcomes of Children and Adolescents Accessing Treatment in Child and Youth Mental Health Services. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2022, 16, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing, 2020–2022|Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/2020-2022 (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Erikson, E.H. Identity and the Life Cycle; W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, D.; Hafekost, J.; Johnson, S.E.; Saw, S.; Buckingham, W.J.; Sawyer, M.G.; Ainley, J.; Zubrick, S.R. Key Findings from the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 876–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGorry, P.D.; Goldstone, S. Is This Normal? Assessing Mental Health in Young People. Aust. Fam. Physician 2011, 40, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ward, D. ‘Recovery’: Does It Fit for Adolescent Mental Health? J. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 2014, 26, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Leamy, M.; Bacon, F.; Janosik, M.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Bird, V. International Differences in Understanding Recovery: Systematic Review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2012, 21, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, W.A. Recovery from Mental IIllness: The Guiding Vision of the Mental Health Service System in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 1990, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonds, L.M.; Pons, R.A.; Stone, N.J.; Warren, F.; John, M. Adolescents with Anxiety and Depression: Is Social Recovery Relevant? Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2014, 21, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; Boutillier, C.L.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Conceptual Framework for Personal Recovery in Mental Health: Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, V.; Leamy, M.; Tew, J.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Fit for Purpose? Validation of a Conceptual Framework for Personal Recovery with Current Mental Health Consumers. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naughton, J.N.L.; Maybery, D.; Sutton, K. Review of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Recovery Literature: Concordance and Contention. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 2018, 5, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weeghel, J.; van Zelst, C.; Boertien, D.; Hasson-Ohayon, I. Conceptualizations, Assessments, and Implications of Personal Recovery in Mental Illness: A Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2019, 42, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallinger, V.C.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; du Plessis, C.; Pillai-Sasidharan, A.; Ayres, A.; Waters, L.; Gloom, Y.; Sweeney, K.; Anderson, L.; Rees, B.; et al. Conceptualisation of Personal Recovery and Recovery-Oriented Care for Youth: Multisystemic Perspectives. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 23, 1308–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, J.N.L.; Maybery, D.; Sutton, K.; Basu, S.; Carroll, M. Is Self-Directed Mental Health Recovery Relevant for Children and Young People? Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moberg, J.; Skogens, L.; Schön, U.K. Review: Young People’s Recovery Processes from Mental Health Problems—A Scoping Review. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 2023, 28, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, S.; Thielking, M.; Lough, R. A New Paradigm of Youth Recovery: Implications for Youth Mental Health Service Provision. Aust. J. Psychol. 2018, 70, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallinger, V.C.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; du Plessis, C.; Pillai-Sasidharan, A.; Ayres, A.; Waters, L.; Groom, Y.; Alston, O.; Anderson, L.; Burton, L. Utilisation of Digital Applications for Personal Recovery amongst Youth with Mental Health Concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 16818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Coughlan, B. A Theory of Youth Mental Health Recovery from a Parental Perspective. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 24, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Human Services Working Together with Families and Carers: Chief Psychiatrist’s Guideline. 2018. Available online: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/files/collections/policies-and-guidelines/c/chief-psychiatrist-guideline-working-with-families-and-carers.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Dixon, L.B.; Dickerson, F.; Bellack, A.S.; Bennett, M.; Dickinson, D.; Goldberg, R.W.; Lehman, A.; Tenhula, W.N.; Calmes, C.; Pasillas, R.M.; et al. The 2009 Schizophrenia PORT Psychosocial Treatment Recommendations and Summary Statements. Schizophr. Bull. 2010, 36, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galletly, C.; Castle, D.; Dark, F.; Humberstone, V.; Jablensky, A.; Killackey, E.; Kulkarni, J.; McGorry, P.; Nielssen, O.; Tran, N. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Schizophrenia and Related Disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 410–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, A.F.; Kreyenbuhl, J.; Buchanan, R.W.; Dickerson, F.B.; Dixon, L.B.; Goldberg, R.; Green-Paden, L.D.; Tenhula, W.N.; Boerescu, D.; Tek, C.; et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): Updated Treatment Recommendations 2003. Schizophr. Bull. 2004, 30, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults: Prevention and Management Clinical Guideline. 2014. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. 2013. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506021 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Public Policy Institute AARP Caregiving in the U.S. 2020—AARP Research Report. 2019. Available online: https://digirepo.nlm.nih.gov/master/borndig/9918434683306676/9918434683306676.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Productivity Commission Annual Report 2019–2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/about/annual-report/2019-20 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Office for National Statistics Unpaid Care and Protected Characteristics, England and Wales: Census 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/socialcare/articles/unpaidcareandprotectedcharacteristicsenglandandwales/census2021 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Hannan, R. Triangle of Care. Nurs. Older People 2014, 26, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; Mian, I.; Charach, A. Promoting Adherence with Children and Adolescents with Psychosis—ProQuest. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. News 2008, 13, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, J.; Moone, N.; Wellman, N. Developing Services for the Carers of Young Adults with Early-Onset Psychosis—Listening to Their Experiences and Needs. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2005, 12, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, G.; Joseph, A. Family-Based Treatment Research: A 10-Year Update. J. Am. Acad. Child. Psychiatry 2005, 44, 872–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, J.; Agras, W.S.; Bryson, S.; Kraemer, H. A Comparison of Short- and Long-Term Family Therapy for Adolescent Anorexia. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2005, 44, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2021, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 1847875815. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R. Critical Realism and the Ontology of Persons. J. Crit. Realism 2020, 19, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; Mccrory, M.; Mackenzie, M.; Mccartney, G. Social Theory and Health Inequalities: Critical Realism and a Transformative Activist Stance? Soc. Theory Health 2015, 13, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.J. Applying Critical Realism in Qualitative Research: Methodology Meets Method. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.M.; Lissel, S.L.; Davis, C. Complex Critical Realism: Tenets and Application in Nursing Research. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2008, 31, E67–E79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.J.; Fuller, C. Symbols, Meaning, and Action: The Past, Present, and Future of Symbolic Interactionism. Curr. Sociol. 2016, 64, 931–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willig, C. Reflections on the Use of Object Elicitation. Qual. Psychol. 2017, 4, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.R. The Necessary and Sufficient Conditions of Therapeutic Personality Change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1992, 60, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, M. Unconditional Love; 2022; Volume 3. Available online: https://sites.create-cdn.net/sitefiles/35/5/3/355387/Unconditional_Love.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Francis, A. Stigma in an Era of Medicalisation and Anxious Parenting: How Proximity and Culpability Shape Middle-Class Parents’ Experiences of Disgrace. Sociol. Health Illn. 2012, 34, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, T. Stigma and Self-Concept among Adolescents Receiving Mental Health Treatment. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2009, 79, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, E. I Blame the Mother: Educating Parents and the Gendered Nature of Parenting Orders. Gend. Educ. 2012, 24, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.; Runswick-Cole, K. Repositioning Mothers: Mothers, Disabled Children and Disability Studies. Disabil. Soc. 2008, 23, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Kelly, K.M. Belonging Motivation; Leary, M.R., Hoyle, R.H., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.R.; Park, J.S. Impact of Attachment, Temperament and Parenting on Human Development. Korean J. Pediatr. 2012, 55, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheinbaum, T.; Kwapil, T.R.; Ballespí, S.; Mitjavila, M.; Chun, C.A.; Silvia, P.J.; Barrantes-Vidal, N. Attachment Style Predicts Affect, Cognitive Appraisals, and Social Functioning in Daily Life. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 124692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneidtinger, C.; Haslinger-Baumann, E. The Lived Experience of Adolescent Users of Mental Health Services in Vienna, Austria: A Qualitative Study of Personal Recovery. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 32, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, M.D.; Bearman, P.S.; Blum, R.W.; Bauman, K.E.; Harris, K.M.; Jones, J.; Tabor, J.; Beuhring, T.; Sieving, R.E.; Shew, M.; et al. Protecting Adolescents from Harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA 1997, 278, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, R.; Oades, L.; Caputi, P. The Experience of Recovery from Schizophrenia: Towards an Empirically Validated Stage Model. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2003, 37, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaniol, L.; Wewiorski, N.J.; Gagne, C.; Anthony, W.A. The Process of Recovery from Schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2002, 14, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Freeman, R.; Sturdy, S. Hope Theory: A Member of the Positive Psychology Family; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, A.; Alchin, S.; Hancock, N. Promoting Mental Health and Wellbeing for a Young Person with a Mental Illness: Parent Occupations. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2014, 61, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA Resilience. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Erikson, E.H. Young Man Luther; Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity Youth and Crisis; W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Rao, D. On the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness: Stages, Disclosure, and Strategies for Change. Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

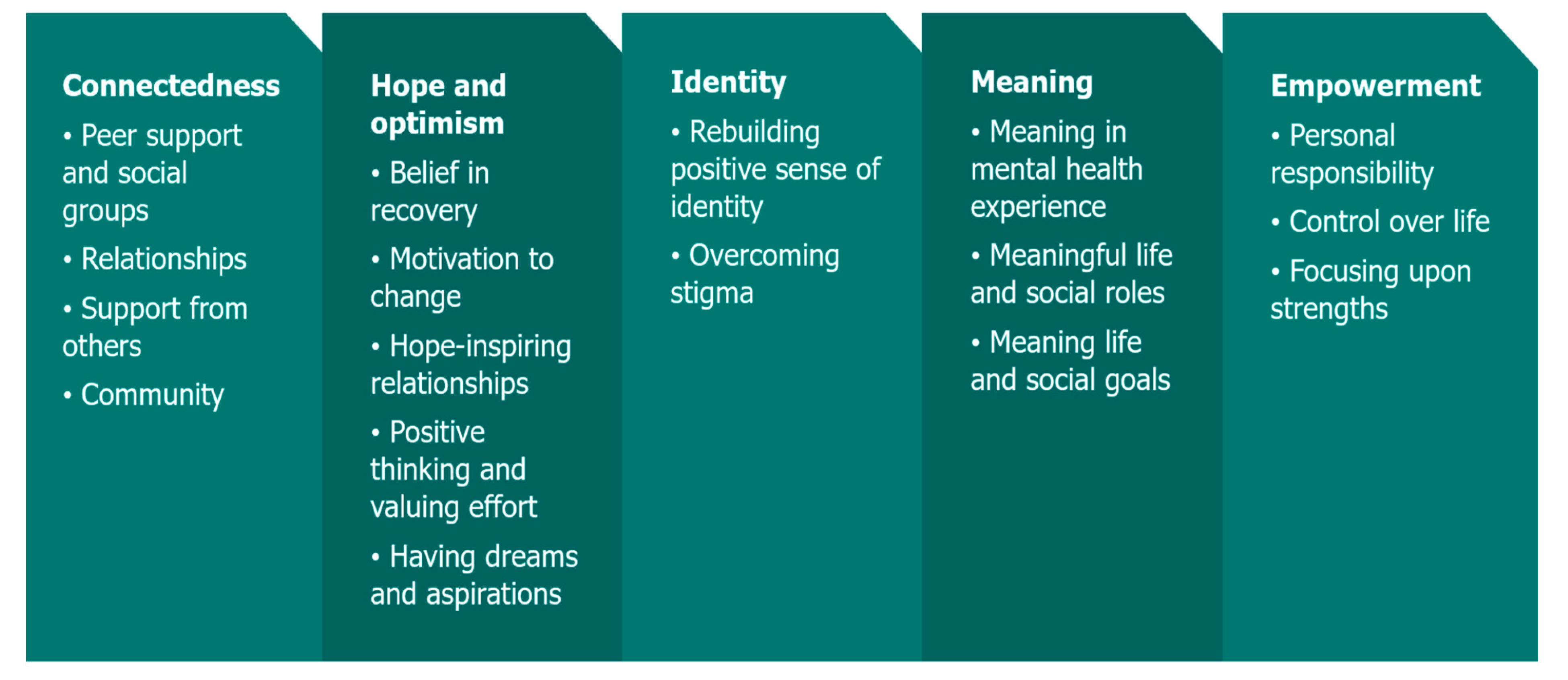

| Main Theme | Illustrative Quote | Corresponding CHIME Acronym |

|---|---|---|

| Providing unconditional love and positive regard | “Unconditional love from family and friends. For us to accept who they are and where they’re at” (Caregiver 4) | Connection |

| Encouraging connection with peers | “... and I say to him, have you messaged your friends? And he’s like “Nah.” And I’m like, do you think you should?” (Caregiver 4) | Connection |

| Co-creating a sense of purpose, meaning, and hope | “Having an idea about what his future looks like […] future goals […] something to work towards [...] that he can hold onto as you are doing day-to-day” (Caregiver 3) | Meaning Connection Hope |

| Supporting assertiveness and advocacy | “I think that’s a big thing for her … being able to make choices … what she feels works and what doesn’t work” (Caregiver 6) | Empowerment Connection |

| Promoting strength and opportunities for mastery | “I think she isn’t a fragile small child that has to be cossetted. Being told that she is a strong, resilient young person who can do this” (Caregiver 2) | Empowerment Identity Connection |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McKern, D.B.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Dallinger, V.C.; Heart, D.; Maybery, D. The Role of Caregivers in Supporting Personal Recovery in Youth with Mental Health Concerns. Children 2025, 12, 787. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060787

McKern DB, Krishnamoorthy G, Dallinger VC, Heart D, Maybery D. The Role of Caregivers in Supporting Personal Recovery in Youth with Mental Health Concerns. Children. 2025; 12(6):787. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060787

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcKern, Denise B., Govind Krishnamoorthy, Vicki C. Dallinger, Diane Heart, and Darryl Maybery. 2025. "The Role of Caregivers in Supporting Personal Recovery in Youth with Mental Health Concerns" Children 12, no. 6: 787. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060787

APA StyleMcKern, D. B., Krishnamoorthy, G., Dallinger, V. C., Heart, D., & Maybery, D. (2025). The Role of Caregivers in Supporting Personal Recovery in Youth with Mental Health Concerns. Children, 12(6), 787. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060787