Dita.te—A Dictation Assessment Instrument with Automatic Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

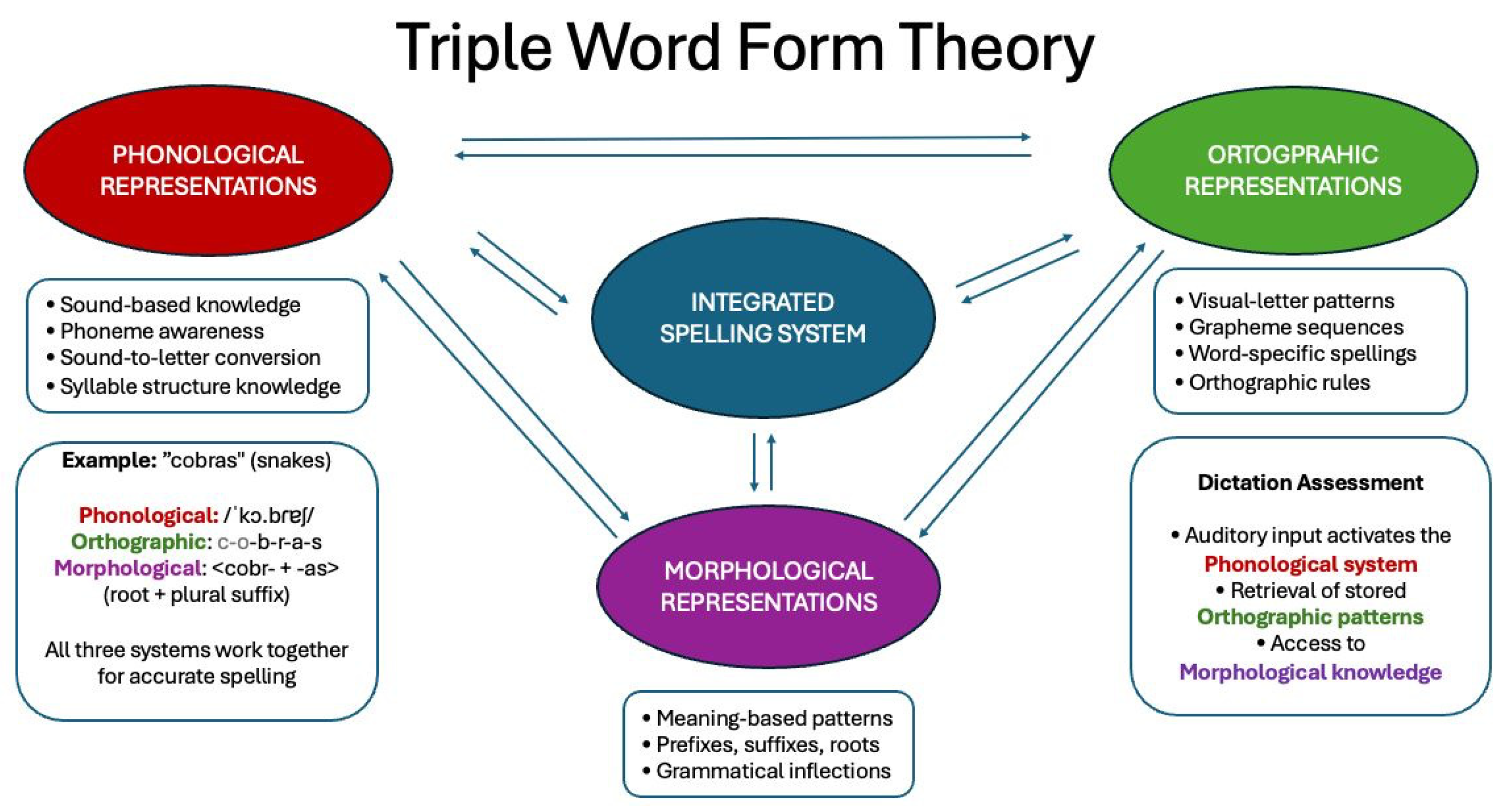

2.1. Instrument Development

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collecztion

2.4. Data Analysis

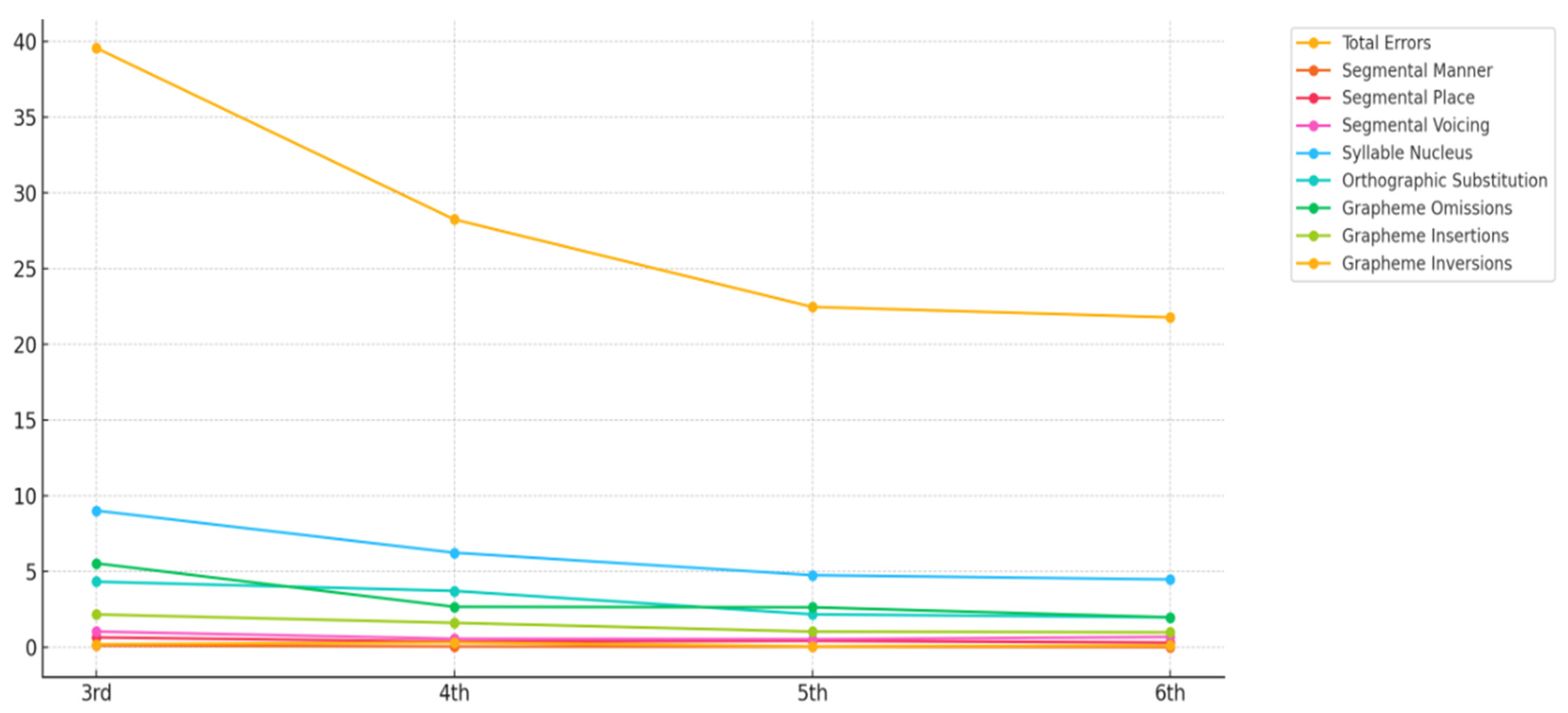

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Reliability of Dita.te

4.2. Developmental Patterns in Orthographic Skills

4.3. Clinical and Educational Implications

4.3.1. Clinical Utility

4.3.2. Pedagogical Benefits

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- The teacher should dictate to the class and record the time taken.

- Privacy dividers should be placed between each student to prevent copying.

- The children should write on standardized lined paper provided by the research team.

- Read, slowly, two or three words at a time or small blocks of information that require you to retain the information (small sentence).

- Do not provide any kind of help that compromises the results obtained.

- Repeat words when asked by a student (once).

- At the top of the sheet, write the student’s initials, grade, class, gender, and date of birth.

- Provide positive reinforcement when necessary, for example: “Very good, we’re almost there…”, “Nice work!”.

References

- Treiman, R.; Kessler, B. How Children Learn to Write Words; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Caravolas, M.; Lervåg, A.; Mousikou, P.; Efrim, C.; Litavský, M.; Onochie-Quintanilla, E.; Salas, N.; Schöffelová, M.; Defior, S.; Mikulajová, M.; et al. Common patterns of prediction of literacy development in different alphabetic orthographies. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Landerl, K.; Ramus, F.; Moll, K.; Lyytinen, H.; Leppänen, P.H.; Lohvansuu, K.; O’Donovan, M.; Williams, J.; Bartling, J.; Bruder, J.; et al. Predictors of developmental dyslexia in European orthographies with varying complexity. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, N.; Broc, L.; Marshall, C.R.; Dockrell, J.E. Spelling Errors in French Elementary School Students: A Linguistic Analysis. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2022, 65, 3456–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, T.L.; Aylward, E.H.; Field, K.M.; Grimme, A.C.; Raskind, W.; Richards, A.L.; Nagy, W.; Eckert, M.; Leonard, C.; Abbott, R.D.; et al. Converging evidence for triple word form theory in children with dyslexia. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2006, 30, 547–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, O.; Moreno, J.; Pereira, M.; Simões, M.R. Developmental dyslexia and phonological processing in European Portuguese orthography. Dyslexia 2015, 21, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, A.R.M. Um estudo sobre a natureza dos erros (orto)gráficos produzidos por crianças dos anos iniciais. Educ. Em Rev. 2020, 36, e221615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, A.; Carvalhais, L.; Limpo, T.; Castro, S.L. Portuguese spelling in primary grades: Complexity, length and lexicality effects. Read. Writ. 2020, 33, 1325–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosse, C.; Parmentier, M.; Van Reybroeck, M. How Do Spelling, Handwriting Speed, and Handwriting Quality Develop During Primary School? Cross-Classified Growth Curve Analysis of Children’s Writing Development. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 685681. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço-Gomes, M.C.; Rodrigues, C.; Alves, I. Escreves como Falas—Falas como escreves? Rev. Rom. 2016, 51, 36–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, R.H.; Silliman, E.R.; Berninger, V.W.; Dow, M. Linguistic pattern analysis of misspellings of typically developing writers in grades 1–9. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2012, 55, 1587–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Knol, D.L.; Stratford, P.W.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. The COSMIN check-list for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: A clarification of its content. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, D.; Correia, P.; Cruz, S.; Fonseca, J.; Ibrahim, S.; Lopes, I.; Lousada, M.; Oliveira, P.; Pinto, C. (Eds.) Compendium de Terapia da Fala—Avaliar e Intervir com Evidência; Sociedade Portuguesa de Terapia da Fala: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Veloso, J. Fonologia e Ortografia do português Europeu in Ensino da Leitura e da Escrita Baseado em Evidências; Nadalim Coord, C.F.P., Alves, R.A., Leite, I., Eds.; Fundação Belmiro de Azevedo: Porto, Portugal, 2022; pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, A.P.; Sousa, O. A análise dos erros ortográficos como instrumento para compreender o desenvolvimento e apoiar o ensino da escrita. In Alfabetização Baseada em Evidências: Da Ciência à Sala de Aula; Sargiani, R., Ed.; Penso: Melgaço, Portugal, 2022; pp. 169–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cifre, M.V.; Coblijn, L. Study of English as an additional language in students with dyslexia. Lang. Health 2025, 3, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, D.; Lousada, M.; Hall, A.; Jesus, L.M. Paediatric Automatic Phonological Analysis Tools (APAT). Logop. Phoniatr. Vocol. 2017, 42, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, A.; Lousada, M.; Lages, A.; Soares, A.P. Automatic phonological analysis of the linguistic productions of Portuguese children with and without language impairment. In Proceedings of the 16th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI 2021), Chaves, Portugal, 23–26 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, C.; Festas, I.; Moreno, J. Para a fundamentação de uma taxonomia de erros de leitura apoiada em critérios linguísticos. In Dislexia: Teoria Avaliação e Intervenção; Moura, O., Pereira, M., Simões, M.R., Eds.; Pactor: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rello, L.; Baeza-Yates, R.; Llisterri, J. DysList: An Annotated Resource of Dyslexic Errors; LREC 2014: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, A.P.; Medeiros, J.C.; Simões, A.; Machado, J.; Costa, A.; Iriarte, Á.; de Almeida, J.J.; Pinheiro, A.P.; Comesaña, M. ESCOLEX: A grade-level lexical database from European Portuguese elementary to middle school textbooks. Behav. Res. Methods 2014, 46, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, A.M.; Almeida, L.; Freitas, M.J. CLCP-PE (Avaliação Fonológica da Criança: Crosslinguistic Child Phonology Project—Português Europeu). Registo IGAC 2014, 67, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, A.M. Aquisição Fonológica na criança: Tradução e Adaptação de um Instrumento de Avaliação Interlinguístico Para o, P.E. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva, D.; Ramalho, A.M.; Rocha, C.; Lousada, M. Análise de escrita: Um estudo piloto em crianças com perturbação da aprendizagem específica. Port. J. Speech Lang. Ther. 2023, 15, 47. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster, K.L.; Shin, J.; Espin, C.A.; Espin, P.G.; Jung, M.M.; Wayman, M.M.; Deno, S.L. Monitoring elementary students’ writing progress using curriculum-based measures: Grade and gender differences. Read. Writ. 2017, 30, 2069–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, D.; Neumann, D.; Andrews, G. Gender differences in reading and writing achievement: Evidence from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Am. Psychologist. 2019, 74, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, J. Gender test score gaps under equal behavioral engagement. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. Reliability Analysis, in SPSS for Windows, Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 222–232. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolchinsky, L. Linguistic patterns of spelling of isolated words to dictation text-composing in Catalan across elementary school. J. Study Educ. Dev. Infanc. Y Aprendiz. 2021, 44, 183–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Lourenço-Gomes, M.C. Representação ortográfica de núcleos nasais na escrita do 2° e 4° ano do Ensino Básico: Dados do português europeu. In Estudos em Fonética e Fonologia—Coletânea em Homenagem a Carmen Matzenhauer; Lazzarotto-Volcão, L., Freitas, M.J., Eds.; Editora CRV: Curitiba, Brazil, 2018; pp. 365–394. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, A.P.S. Tipo de erros e dificuldades na escrita de palavras de crianças portuguesas com dislexia. Investig. Práticas Estud. Nat. Educ. 2017, 7, 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, C.; Capelas, S.; Sá Couto, P.; Lousada, M. Morphological awareness, reading and writing in the primary school. Rev. De Estud. Da Ling. 2024, 32, 578–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direção-Geral da Educação. Ilha do Periscópio: Recursos Educativos Digitais Para o 1.° Ciclo. 2022 [Plataforma Educacional]. Available online: https://redge.dge.mec.pt/ilha/periscopio/topic-list/VHeK8k6wnjQ5AFxaEhYh (accessed on 9 June 2025).

| Linguistic Criteria | Examples |

|---|---|

| Word grammatical class | Nouns, verbs, verbs + Pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, numerical quantifiers, pronouns, determiners, prepositions, contractions (preposition + article), interjection |

| Distinctive features | Voicing, place, manner |

| Syllabic structure | V, V(N), VG, VG(N), VGC, VC, V(N)C, CV, CV(N), CVG/CGV, CVG(N), CVC, CVGC, CVG(N)C, CV(N)C, CCV, CCV(N), CCVC, CCVG |

| Word stress | Strong, weak |

| Position within the word | Initial, medial, final |

| Word length | Monosyllables, disyllables, trisyllables, polysyllables |

| Morphological criteria | Errors with clitic pronouns and word boundary errors |

| Year of Schooling | Female (%) | Male (%) | Mean Age ± DP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd | 23 (37.1%) | 39 (62.9%) | 8.35 ± 0.52 |

| 4th | 26 (41.3%) | 37 (58.7%) | 9.27 ± 0.45 |

| 5th | 42 (56.8%) | 32 (43.2%) | 10.46 ± 0.50 |

| 6th | 69 (59.5%) | 47 (40.5%) | 11.31 ± 0.50 |

| Total | 160 (50.8%) | 155 (49.2%) | - |

| School Year | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Mean Difference (vs. Previous Grade) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd grade (n = 62) | 165.05 | 16.289 | 123 | 191 | - |

| 4th grade (n= 63) | 172.79 | 16.205 | 129 | 192 | 7.74 |

| 5th grade (n = 74) | 176.32 | 11.568 | 136 | 191 | 3.53 |

| 6th grade (n = 116) | 176.76 | 10.597 | 138 | 192 | 0.44 |

| Percentiles | Number of Correctly Written Words | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd Grade | 4th Grade | 5th Grade | 6th Grade | |

| 5 | 131.30 | 132.00 | 154.00 | 155.70 |

| 10 | 136.60 | 141.80 | 158.00 | 162.70 |

| 25 | 158.00 | 167.00 | 171.00 | 172.00 |

| 50 | 166.50 | 177.00 | 179.50 | 177.50 |

| 75 | 176.00 | 186.00 | 184.00 | 185.00 |

| 90 | 185.70 | 188.60 | 188.00 | 189.00 |

| 95 | 190.85 | 189.80 | 188.25 | 190.00 |

| School Year | Errors | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | P25 | 950 | P75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd grade (n = 62) | Total number of errors | 39.55 | 26.388 | 2 | 105 | 19.50 | 36.00 | 54.00 |

| Segmental substitution errors by manner | 0.13 | 0.338 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Segmental substitution errors by place | 0.66 | 1.159 | 0 | 5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Segmental substitution errors by voicing | 1.05 | 1.530 | 0 | 6 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | |

| Errors affecting the syllable nucleus | 9.03 | 8.049 | 0 | 36 | 3.75 | 6.50 | 13.00 | |

| Orthographic substitution errors | 4.34 | 3.715 | 0 | 13 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 7.00 | |

| Grapheme omissions | 5.55 | 7.130 | 0 | 33 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 7.25 | |

| Grapheme insertions | 2.18 | 2.532 | 0 | 10 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | |

| Grapheme inversions | 0.21 | 0.577 | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 4th grade (n = 63) | Total number of errors | 28.24 | 25.193 | 1 | 112 | 10.00 | 22.00 | 33.00 |

| Segmental substitution errors by manner | 0.06 | 0.304 | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Segmental substitution errors by place | 0.38 | 0.728 | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Segmental substitution errors by voicing | 0.57 | 0.875 | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Errors affecting the syllable nucleus | 6.25 | 7.128 | 0 | 29 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 7.00 | |

| Orthographic substitution errors | 3.73 | 4.502 | 0 | 23 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 5.00 | |

| Grapheme omissions | 2.68 | 3.325 | 0 | 16 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | |

| Grapheme insertions | 1.62 | 2.648 | 0 | 13 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | |

| Grapheme inversions | 0.33 | 1.032 | 0 | 5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 5th grade (N = 74) | Total number of errors | 22.47 | 18.218 | 1 | 89 | 10.75 | 17.00 | 28.25 |

| Segmental substitution errors by manner | 0.05 | 0.228 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Segmental substitution errors by place | 0.43 | 0.812 | 0 | 4 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Segmental substitution errors by voicing | 0.54 | 0.814 | 0 | 4 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Errors affecting the syllable nucleus | 4.77 | 4.153 | 0 | 20 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 6.00 | |

| Orthographic substitution errors | 2.19 | 2.065 | 0 | 9 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | |

| Grapheme omissions | 2.65 | 4.305 | 0 | 27 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | |

| Grapheme insertions | 1.05 | 1.507 | 0 | 8 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.25 | |

| Grapheme inversions | 0.07 | 0.253 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 6th grade (n = 116) | Total number of errors | 21.78 | 19.023 | 1 | 148 | 10.00 | 18.00 | 28.75 |

| Segmental substitution errors by manner | 0.03 | 0.159 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Segmental substitution errors by place | 0.32 | 0.537 | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Segmental substitution errors by voicing | 0.69 | 1.075 | 0 | 6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Errors affecting the syllable nucleus | 4.49 | 3.722 | 0 | 24 | 2.00 | 3.50 | 6.00 | |

| Orthographic substitution errors | 1.99 | 1.931 | 0 | 9 | 0.25 | 1.50 | 3.00 | |

| Grapheme omissions | 1.99 | 2.462 | 0 | 15 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | |

| Grapheme insertions | 1.00 | 1.389 | 0 | 6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | |

| Grapheme inversions | 0.13 | 0.428 | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saraiva, D.; Ramalho, A.M.; Valente, A.R.; Rocha, C.; Lousada, M. Dita.te—A Dictation Assessment Instrument with Automatic Analysis. Children 2025, 12, 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060774

Saraiva D, Ramalho AM, Valente AR, Rocha C, Lousada M. Dita.te—A Dictation Assessment Instrument with Automatic Analysis. Children. 2025; 12(6):774. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060774

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaraiva, Daniela, Ana Margarida Ramalho, Ana Rita Valente, Cláudia Rocha, and Marisa Lousada. 2025. "Dita.te—A Dictation Assessment Instrument with Automatic Analysis" Children 12, no. 6: 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060774

APA StyleSaraiva, D., Ramalho, A. M., Valente, A. R., Rocha, C., & Lousada, M. (2025). Dita.te—A Dictation Assessment Instrument with Automatic Analysis. Children, 12(6), 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060774