Callous–Unemotional Traits and Gun Violence: The Unique Role of Maternal Hostility

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Parenting Practices and CU Traits

1.2. Theoretical Framework

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analytics Plan

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

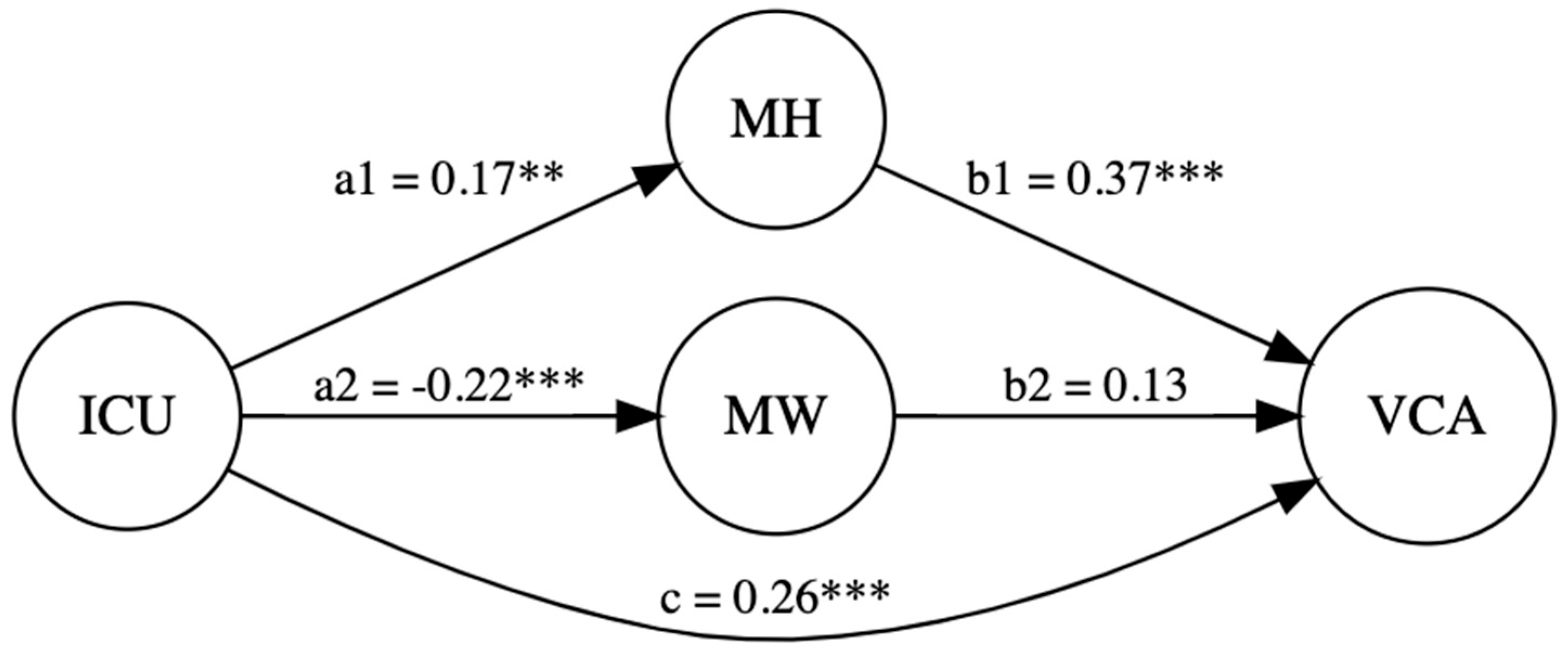

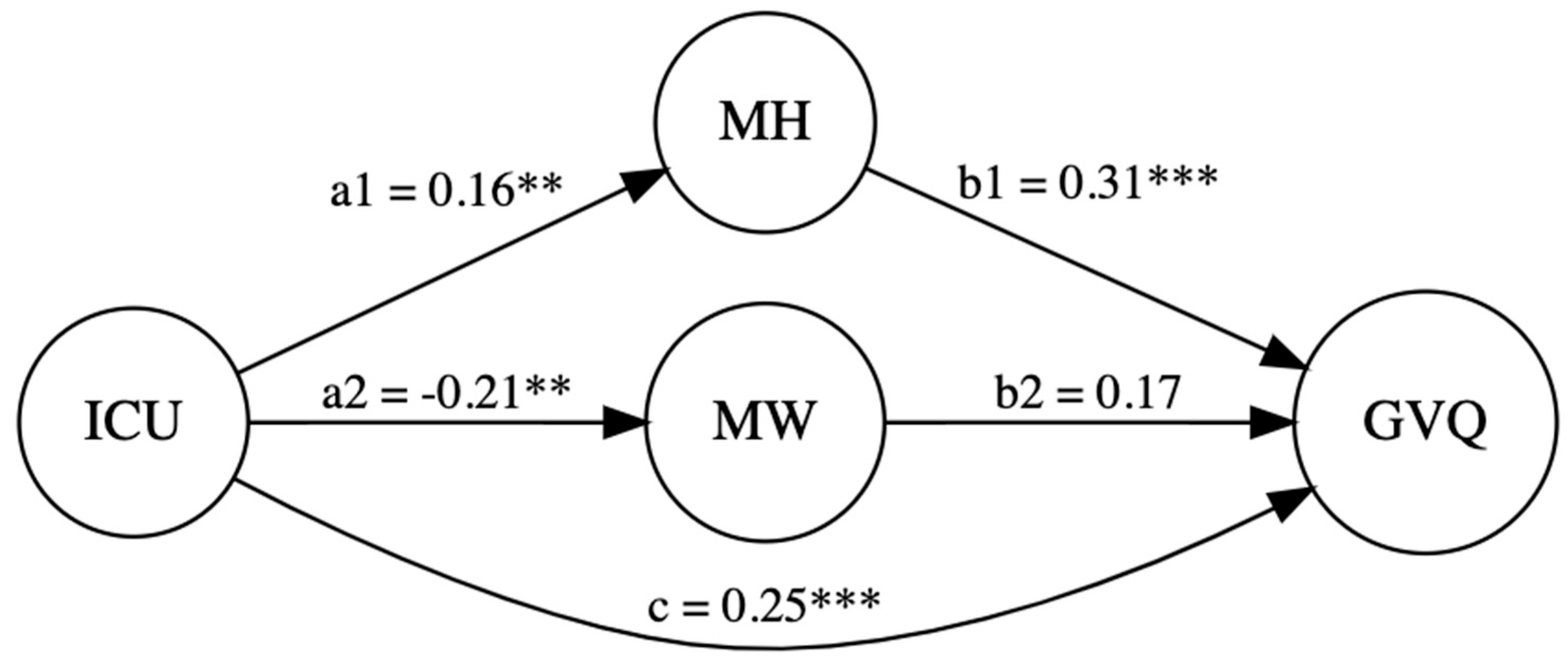

3.2. Maternal Parenting Practices

3.3. Paternal Parenting Practices

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erskine, H.E.; Ferrari, A.J.; Polanczyk, G.V.; Moffitt, T.E.; Murray, C.J.L.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A.; Scott, J.G. The global burden of conduct disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in 2010. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2014, 55, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, N.D.; Kjærvik, S.L.; Blondell, V.J.; Hazlett, L.E. The interplay between fear reactivity and callous–unemotional traits predicting reactive and proactive aggression. Children 2024, 11, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th-Text Revision ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Erskine, H.E.; Norman, R.E.; Ferrari, A.J.; Chan, G.C.; Copeland, W.E.; Whiteford, H.A.; Scott, J.G. Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E. Life-course-persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behavior. In Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 3, pp. 570–598. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero, N.L.; Moffitt, T.E. Can childhood factors predict workplace deviance? Justice Q. 2014, 31, 664–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.; Costello, E.J.; Angold, A.; Copeland, W.E.; Maughan, B. Developmental pathways in oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010, 119, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Kazdin, A.E.; Hiripi, E.; Kessler, R.C. Prevalence, subtypes, and correlates of DSM-IV conduct disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, E.C. Developmental trajectories of conduct problems across racial/ethnic identity and neighborhood context: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2023, 71, 101844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centifanti, L.C.M.; Shaw, H.; Atherton, K.J.; Thomson, N.D.; MacLellan, S.; Frick, P.J. CAPE for measuring callous-unemotional traits in disadvantaged families: A cross-sectional validation study. F1000Research 2020, 8, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, P.J. Clinical Assessment of Prosocial Emotions (CAPE 1.1, Unpublished Rating Scale); (Version 1.1) [Computer software]; 2013.

- Frick, P.J.; Ray, J.V.; Thornton, L.C.; Kahn, R.E. Annual Research Review: A developmental psychopathology approach to understanding callous-unemotional traits in children and adolescents with serious conduct problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulter, N.; Craig, S.G.; McMahon, R.J. Primary and secondary callous–unemotional traits in adolescence are associated with distinct maladaptive and adaptive outcomes in adulthood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021, 35, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salekin, R.T.; Bellamy, N.A.; DeGroot, H.R.; Avellan, J.J.; Butler, I.G.; Grant, J.C. Future Directions for Conduct Disorder and Psychopathic Trait Specifiers. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2025, 54, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabris, M.A.; Settanni, M.; Longobardi, C.; Marengo, D. Sense of belonging at school and on social media in adolescence: Associations with educational achievement and psychosocial maladjustment. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2024, 55, 1620–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, P.J.; Ray, J.V.; Thornton, L.C.; Kahn, R.E. Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulter, N.; McMahon, R.J.; Pasalich, D.S.; Dodge, K.A. Indirect effects of early parenting on adult antisocial outcomes via adolescent conduct disorder symptoms and callous-unemotional traits. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2020, 49, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, V.; Eapen, V.; Hawkins, E.; Kohlhoff, J. Parenting characteristics and callous-unemotional traits in children aged 0–6 years: A systematic narrative review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotterer, H.L.; Burt, S.A.; Klump, K.L.; Hyde, L.W. Associations between parental psychopathic traits, parenting, and adolescent callous-unemotional traits. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 1431–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Gardner, F.; Hyde, L.W. What are the associations between parenting, callous-unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, C.A.; Murphy, J.L.; Matijczak, A.; Califano, A.; Santos, J.; McDonald, S.E. The link between family violence and animal cruelty: A scoping review. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasalich, D.S.; Dadds, M.R.; Hawes, D.J.; Brennan, J. Do callous-unemotional traits moderate the relative importance of parental coercion versus warmth in child conduct problems? An observational study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2011, 52, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, D.A.; Lochman, J.E.; Powell, N. The development of callous-unemotional traits and antisocial behavior in children: Are there shared and/or unique predictors? J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2007, 36, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, S.G.; Goulter, N.; Andrade, B.F.; McMahon, R.J. Developmental precursors of primary and secondary callous-unemotional traits in youth. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023, 54, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Aggression: A Social Learning Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, N.D. Handbook of Gun Violence; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, G.R. Coercion theory: The study of change. In The Oxford Handbook of Coercive Relationship Dynamics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, P.J.; White, S.F. Research Review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2008, 49, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988; p. xii, 205. [Google Scholar]

- Fearon, R.P.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Lapsley, A.; Roisman, G.I. The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children’s externalizing behavior: A meta-analytic study. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasalich, D.S.; Dadds, M.R.; Hawes, D.J.; Brennan, J. Attachment and callous-unemotional traits in children with early-onset conduct problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasalich, D.S.; Waschbusch, D.A.; Dadds, M.R.; Hawes, D.J. Emotion socialization style in parents of children with callous–unemotional traits. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2014, 45, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backman, H.; Laajasalo, T.; Jokela, M.; Aronen, E.T. Parental warmth and hostility and the development of psychopathic behaviors: A longitudinal study of young offenders. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, E.P.; Frick, P.J.; Ray, J.V.; Robertson, E.L.; Thornton, L.C.; Myers, T.D.W.; Steinberg, L.; Cauffman, E. The associations of maternal warmth and hostility with prosocial and antisocial outcomes in justice-involved adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 2179–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimonis, E.R.; Fleming, G.; Briggs, N.; Brouwer-French, L.; Frick, P.J.; Hawes, D.J.; Bagner, D.M.; Thomas, R.; Dadds, M. Parent-child interaction therapy adapted for preschoolers with callous-unemotional traits: An open trial pilot study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 48, S347–S361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, R.P.; Khaleque, A.; Cournoyer, D.E. Parental Acceptance-Rejection: Theory, Methods, Cross-Cultural Evidence, and Implications. Ethos 2005, 33, 299–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, L.W.; Waller, R.; Trentacosta, C.J.; Shaw, D.S.; Neiderhiser, J.M.; Ganiban, J.M.; Reiss, D.; Leve, L.D. Heritable and Nonheritable Pathways to Early Callous-Unemotional Behaviors. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S.; Cicchetti, D. Developmental cascades. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardslee, J.; Docherty, M.; Mulvey, E.; Schubert, C.; Pardini, D. Childhood risk factors associated with adolescent gun carrying among Black and White males: An examination of self-protection, social influence, and antisocial propensity explanations. Law Hum. Behav. 2018, 42, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, E.L.; Frick, P.J.; Walker, T.M.; Kemp, E.C.; Ray, J.V.; Thornton, L.C.; Myers, T.D.W.; Steinberg, L.; Cauffman, E. Callous-unemotional traits and risk of gun carrying and use during crime. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WISQARS—Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System [Computer Software]. 2024. Available online: https://wisqars.cdc.gov/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Dadds, M.R.; Rhodes, T. Aggression in young children with concurrent callous–unemotional traits: Can the neurosciences inform progress and innovation in treatment approaches? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 2567–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, K.A.; Frick, P.J.; Georgiou, S. Linking callous-unemotional traits to instrumental and non-instrumental forms of aggression. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2009, 31, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, D.A. The callousness pathway to severe violent delinquency. Aggress. Behav. 2006, 32, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, D.A.; Beardslee, J.; Docherty, M.; Schubert, C.; Mulvey, E. Risk and protective factors for gun violence in male juvenile offenders. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2021, 50, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimonis, E.R.; Frick, P.J.; Skeem, J.L.; Marsee, M.A.; Cruise, K.; Munoz, L.C.; Aucoin, K.J.; Morris, A.S. Assessing callous–unemotional traits in adolescent offenders: Validation of the Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2008, 31, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R.D.; Ge, X.; Elder, G.H.; Lorenz, F.O.; Simons, R.L. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, A.; Dodge, K.; Loeber, R.; Gatzke-Kopp, L.; Lynam, D.; Reynolds, C.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M.; Liu, J. The Reactive–Proactive Aggression Questionnaire: Differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggress. Behav. 2006, 32, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine, N.M.G.; McCrory, E.J.P.; Boivin, M.; Moffitt, T.E.; Viding, E. Predictors and outcomes of joint trajectories of callous–unemotional traits and conduct problems in childhood. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011, 120, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Gardner, F.; Hyde, L.W.; Shaw, D.S.; Dishion, T.J.; Wilson, M.N. Do harsh and positive parenting predict parent reports of deceitful-callous behavior in early childhood? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Mosher, W. Fathers’ Involvement with Their Children: United States, 2006–2010; National Health Statistics Reports, 71; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2013.

- Hoeve, M.; Dubas, J.S.; Eichelsheim, V.I.; van der Laan, P.H.; Smeenk, W.; Gerris, J.R.M. The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 749–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, N.D.; Moeller, F.G.; Amstadter, A.B.; Svikis, D.; Perera, R.A.; Bjork, J.M. The impact of parental incarceration on psychopathy, crime, and prison violence in women. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2020, 64, 1178–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wootton, J.M.; Frick, P.J.; Shelton, K.K.; Silverthorn, P. Ineffective parenting and childhood conduct problems: The moderating role of callous-unemotional traits. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 65, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K.E.; Shanholtz, C.E.; Espeleta, H.C.; Ridings, L.E.; Gavrilova, Y.; Hink, A.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Davidson, T.M. Mental health symptoms and engagement in a stepped-care mental health service among patients with a violent versus nonviolent injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2024, 96, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, L.; Feder, M.; Abar, B.; Winsler, A. Relations between parenting stress, parenting style, and child executive functioning for children with ADHD or autism. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 3644–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Fathers’ parenting stress, parenting styles and children’s problem behavior: The mediating role of parental burnout. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 25683–25695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, N.D.; Kevorkian, S.S.; Hazlett, L.; Perera, R.; Vrana, S. A new treatment approach to conduct disorder and callous-unemotional traits: An assessment of the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of Impact VR. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1484938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | |||||||||

| 0.004 | - | ||||||||

| 0.04 | −0.18 * | - | |||||||

| 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | - | ||||||

| −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.29 ** | - | |||||

| −0.001 | 0.19 * | −0.11 | 0.27 ** | 0.25 ** | - | ||||

| 0.13 | −0.36 ** | −0.007 | 0.12 | 0.31 ** | 0.17 * | - | |||

| −0.13 | 0.27 ** | 0.01 | −0.19 * | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.55 ** | - | ||

| 0.09 | −0.09 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.26 ** | −0.06 | - | |

| −0.09 | 0.20 * | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.15 * | 0.34 ** | −0.20 * | - |

| Mean | 15.68 | 0.68 | 0.57 | 22.87 | 1.31 | 0.27 | 4.80 | 20.08 | 3.88 | 16.06 |

| SD | 1.36 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 8.49 | 1.72 | 0.54 | 3.60 | 6.17 | 4.50 | 8.88 |

| Skewness | −0.58 | −0.77 | −0.29 | 0.70 | 1.55 | 2.24 | 1.77 | −0.79 | 2.13 | −0.39 |

| Kurtosis | −0.86 | −1.42 | −1.92 | 0.61 | 2.05 | 4.74 | 4.09 | −0.19 | 5.38 | −1.11 |

| Pathways | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Violent Crime | ||||

| Total effect | 0.06 * | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Direct effects | ||||

| CU traits → maternal hostility | 0.07 * | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13 |

| CU traits → maternal warmth | −0.09 * | 0.05 | −0.26 | −0.07 |

| CU traits → violent crime | 0.05 * | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Maternal hostility → violent crime | 0.18 * | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.26 |

| Maternal warmth → violent crime | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.003 | 0.08 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| CU traits → maternal hostility → violent crime | 0.01 * | 0.007 | 0.01 | 0.14 |

| CU traits → maternal warmth → violent crime | −0.006 | 0.004 | −0.07 | 0.002 |

| Gun Violence | ||||

| Total effect | 0.02 * | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.02 |

| Direct effects | ||||

| CU traits → maternal hostility | 0.07 * | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| CU traits → maternal warmth | −0.15 * | 0.05 | −0.25 | −0.07 |

| CU traits → gun violence | 0.02 * | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.02 |

| Maternal hostility → gun violence | 0.05 * | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Maternal warmth → gun violence | 0.01 | 0.008 | −0.0002 | 0.03 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| CU traits → maternal hostility → gun violence | 0.003 * | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| CU traits → maternal warmth → gun violence | −0.002 | 0.001 | −0.006 | 0.000 |

| Pathways | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Violent Crime | ||||

| Total effect | 0.06 * | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Direct effects | ||||

| CU traits → paternal hostility | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.13 |

| CU traits → paternal warmth | −0.11 | 0.08 | −0.28 | 0.05 |

| CU traits → violent crime | 0.06 * | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Paternal hostility →violent crime | −0.008 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Paternal warmth → violent crime | 0.006 | 0.23 | −0.02 | 0.04 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| CU traits → paternal hostility → violent crime | −0.0004 | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.002 |

| CU traits → paternal warmth → violent crime | −0.0007 | 0.002 | −0.006 | 0.004 |

| Gun Violence | ||||

| Total effect | 0.02 * | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Direct effects | ||||

| CU traits → paternal hostility | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.12 |

| CU traits → paternal warmth | −0.10 | 0.08 | −0.27 | 0.05 |

| CU traits → gun violence | 0.02 * | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.03 |

| Paternal hostility → gun violence | 0.007 | 0.007 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Paternal warmth → gun violence | 0.001 | 0.0006 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| CU traits → paternal hostility → gun violence | 0.0003 | 0.0008 | −0.0009 | 0.003 |

| CU traits → paternal warmth → gun violence | −0.0001 | 0.0008 | −0.002 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thomson, N.D.; Kjærvik, S.L.; Zacharaki, G.; Gresham, A.M.; Dick, D.M.; Fanti, K.A. Callous–Unemotional Traits and Gun Violence: The Unique Role of Maternal Hostility. Children 2025, 12, 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060775

Thomson ND, Kjærvik SL, Zacharaki G, Gresham AM, Dick DM, Fanti KA. Callous–Unemotional Traits and Gun Violence: The Unique Role of Maternal Hostility. Children. 2025; 12(6):775. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060775

Chicago/Turabian StyleThomson, Nicholas D., Sophie L. Kjærvik, Georgia Zacharaki, Abriana M. Gresham, Danielle M. Dick, and Kostas A. Fanti. 2025. "Callous–Unemotional Traits and Gun Violence: The Unique Role of Maternal Hostility" Children 12, no. 6: 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060775

APA StyleThomson, N. D., Kjærvik, S. L., Zacharaki, G., Gresham, A. M., Dick, D. M., & Fanti, K. A. (2025). Callous–Unemotional Traits and Gun Violence: The Unique Role of Maternal Hostility. Children, 12(6), 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060775