Construct Validity and Internal Consistency of the Italian Version of the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scale and PedsQLTM 3.0 Cerebral Palsy Module

Abstract

1. Introduction

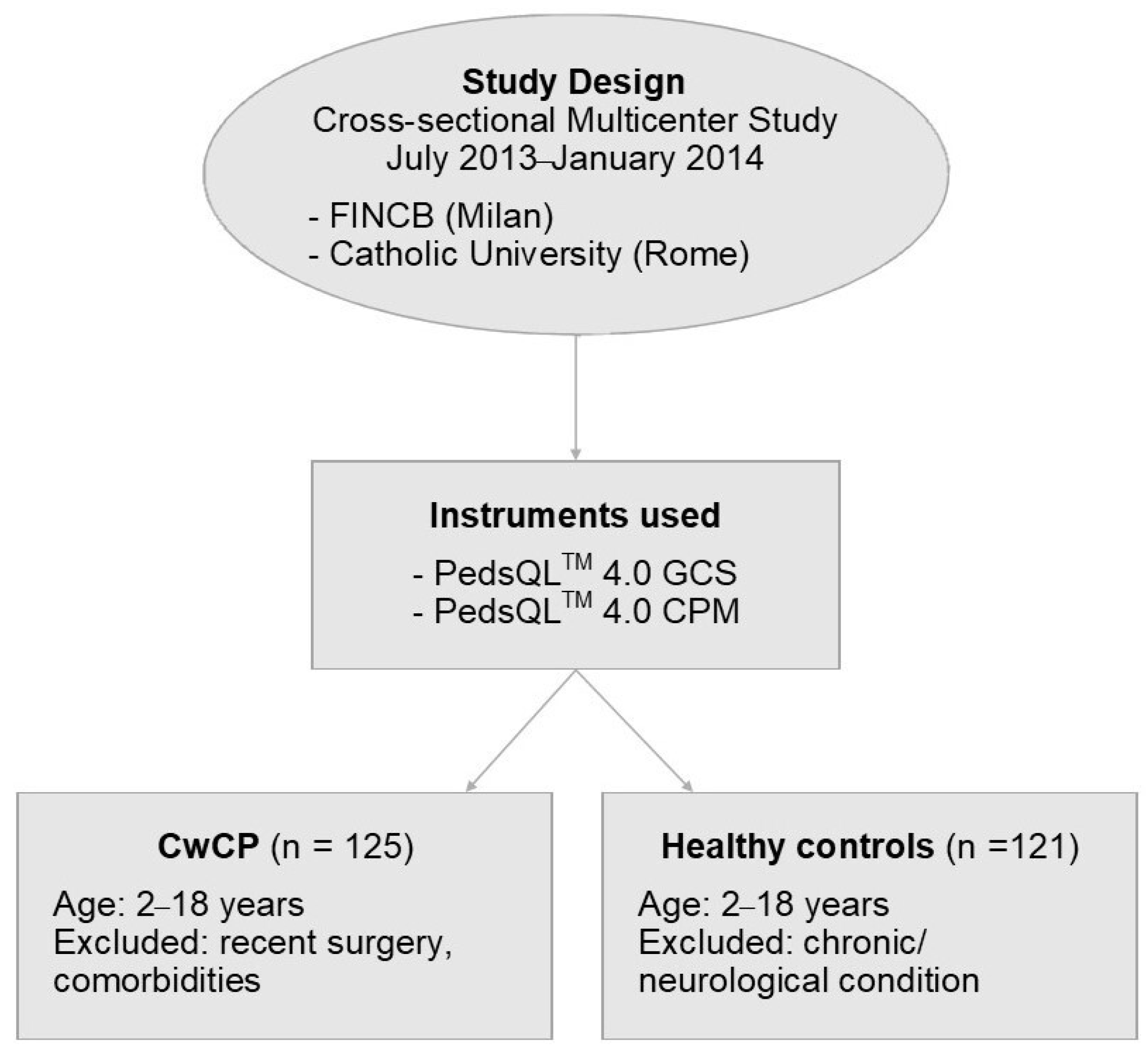

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.1.1. CwCP Sample

2.1.2. Healthy Children Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. PedsQLTM 4.0 GCS

2.2.2. PedsQLTM 3.0 CPM

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.3.1. Factorial Structure

2.3.2. Internal Consistency and Construct Validity

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Dimensionality, Internal Consistency, and Construct Validity

3.3. Parent–Child Concordance

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McIntyre, S.; Goldsmith, S.; Webb, A.; Ehlinger, V.; Hollung, S.J.; McConnell, K.; Arnaud, C.; Smithers-Sheedy, H.; Oskoui, M.; Khandaker, G.; et al. Global Prevalence of Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 1494–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health—Version for Children and Youth; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, H.O.; Parkinson, K.N.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Schirripa, G.; Thyen, U.; Arnaud, C.; Beckung, E.; Fauconnier, J.; McManus, V.; Michelsen, S.I.; et al. Self-Reported Quality of Life of 8–12-Year-Old Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Cross-Sectional European Study. Lancet 2007, 369, 2171–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, G.A.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; King, S.M. Evaluating Family-Centred Service Using a Measure of Parents’ Perceptions. Child Care Health Dev. 1997, 23, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, M.H.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Russell, D.J.; Palisano, R.J. Quality of Life among Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: What Does the Literature Tell Us? Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlon, S.; Shields, N.; Yong, K.; Gilmore, R.; Sakzewski, L.; Boyd, R. A Systematic Review of the Psychometric Properties of Quality of Life Measures for School Aged Children with Cerebral Palsy. BMC Pediatr. 2010, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.; Mackinnon, A.; Davern, M.; Boyd, R.; Bohanna, I.; Waters, E.; Graham, H.K.; Reid, S.; Reddihough, D. Description and Psychometric Properties of the CP QOL-Teen: A Quality of Life Questionnaire for Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Limbers, C.A.; Burwinkle, T.M. Impaired Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Conditions: A Comparative Analysis of 10 Disease Clusters and 33 Disease Categories/Severities Utilizing the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.M.; Terjesen, T.; Jahnsen, R.B.; Diseth, T.H.; Ramstad, K. Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy; a Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Population-Based Study. Child Care Health Dev. 2022, 49, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.; Davis, E.; Ronen, G.M.; Rosenbaum, P.; Livingston, M.; Saigal, S. Quality of Life Instruments for Children and Adolescents with Neurodisabilities: How to Choose the Appropriate Instrument. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2009, 51, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A Report: The Definition and Classification of Cerebral Palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.L.; Silberstein, C.E.; Atkins, E.A.; Harryman, S.E.; Sponseller, P.D.; Hadley-Miller, N.A. Comparing Reliability and Validity of Pediatric Instruments for Measuring Health and Well-Being of Children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2002, 44, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varni, J.W.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Berrin, S.J.; Sherman, S.A.; Artavia, K.; Malcarne, V.L.; Chambers, H.G. The PedsQL in Pediatric Cerebral Palsy: Reliability, Validity, and Sensitivity of the Generic Core Scales and Cerebral Palsy Module. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Kurtin, P.S. PedsQLTM 4.0: Reliability and Validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life InventoryTM Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales in Healthy and Patient Populations. Med. Care 2001, 39, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palisano, R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Walter, S.; Russell, D.; Wood, E.; Galuppi, B. Development and Reliability of a System to Classify Gross Motor Function in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, A.-C.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L.; Rösblad, B.; Beckung, E.; Arner, M.; Öhrvall, A.-M.; Rosenbaum, P. The Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) for Children with Cerebral Palsy: Scale Development and Evidence of Validity and Reliability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiz, D.M.; Foxcroft, C.D.; Povey, J.-L. The Griffiths Scales of Mental Development: A Factorial Validity Study. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2006, 36, 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannio Fancello, G.; Cianchetti, C. WPPSI-III. Contributo alla Taratura Italiana; Giunti OS Organizzazioni Speciali: Florence, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini, A.; Picone, L. WISC-III. Contributo alla Taratura Italiana; Organizzazioni Speciali: Florence, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Technometrics 1988, 31, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehlik-Barry, K.; Babinec, A.J. Data Analysis with IBM SPSS Statistics; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, U.G.; Fehlings, D.; Weir, S.; Knights, S.; Kiran, S.; Campbell, K. Initial Development and Validation of the Caregiver Priorities and Child Health Index of Life with Disabilities (CPCHILD). Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Gosch, A.; Rajmil, L.; Erhart, M.; Bruil, J.; Duer, W.; Auquier, P.; Power, M.; Abel, T.; Czemy, L.; et al. KIDSCREEN-52 Quality-of-Life Measure for Children and Adolescents. Expert Rev. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2005, 5, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xiao, N.; Yan, J. The PedsQL in Pediatric Cerebral Palsy: Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 Generic Core Scales and 3.0 Cerebral Palsy Module. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 20, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantilipikorn, P.; Watter, P.; Prasertsukdee, S. Feasibility, Reliability and Validity of the Thai Version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 3.0 Cerebral Palsy Module. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 22, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colver, A.F.; Dickinson, H.O. Study Protocol: Determinants of Participation and Quality of Life of Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: A Longitudinal Study (SPARCLE2). BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majnemer, A.; Shevell, M.; Rosenbaum, P.; Law, M.; Poulin, C. Determinants of Life Quality in School-Age Children with Cerebral Palsy. J. Pediatr. 2007, 151, 470–475.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelly, A.; Davis, E.; Waters, E.; Mackinnon, A.; Reddihough, D.; Boyd, R.; Reid, S.; Graham, H.K. The Relationship between Quality of Life and Functioning for Children with Cerebral Palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008, 50, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization; WHO Basic Documents: Geneva, Switzerland, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Eiser, C.; Morse, R. The Measurement of Quality of Life in Children: Past and Future Perspectives. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2001, 22, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, I.; M Bova, S.; Fazzi, E.; Ricci, D.; Tinelli, F.; Montomoli, C.; Rezzani, C.; Balottin, U.; Orcesi, S. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measure for Children Born Preterm: Validation of the SOLE VLBWI Questionnaire, a New Quality of Life Self-Assessment Tool. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 58, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidecker, M.J.C.; Paneth, N.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Kent, R.D.; Lillie, J.; Eulenberg, J.B.; Chester, K., Jr.; Johnson, B.; Michalsen, L.; Evatt, M.; et al. Developing and validating the Communication Function Classification System for individuals with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011, 53, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranello, G.; Signorini, S.; Tinelli, F.; Guzzetta, A.; Pagliano, E.; Rossi, A.; Foscan, M.; Tramacere, I.; Romeo, D.M.M.; Ricci, D.; et al. Visual Function Classification System for children with cerebral palsy: Development and validation. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CwCP | Healthy Sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Total n | 125 | 121 |

| Mean age (SD) | 8 (4.8) | 8.4 (4.4) |

| Age range | 2–18 | 2–18 |

| Male (%) | 80 (64%) | 66 (54.5%) |

| Born at term (%) | 60 (48%) | - |

| Born preterm (%) | 65 (52%) | - |

| n | Items, n | % of Variability Explained by the First Dimension | Number of Eigenvalues > 1 | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Core Scales Child Self-report | |||||

| Total Score | 60 | 23 | 22 | 7 | 0.83 |

| Physical Functioning | 60 | 8 | 45 | 2 | 0.79 |

| Psychosocial Health | 60 | 15 | 25 | 6 | 0.79 |

| Emotional Functioning | 60 | 5 | 42 | 1 | 0.61 |

| Social Functioning | 60 | 5 | 38 | 2 | 0.58 |

| School Functioning | 60 | 5 | 41 | 2 | 0.61 |

| Parent Proxy-report Total Score | 125 | 23 | 34 | 5 | 0.91 |

| Physical Functioning | 125 | 8 | 55 | 1 | 0.86 |

| Psychosocial Health | 125 | 15 | 37 | 4 | 0.88 |

| Emotional Functioning | 125 | 5 | 48 | 1 | 0.71 |

| Social Functioning | 125 | 5 | 49 | 2 | 0.74 |

| School Functioning | 125 | 5 | 56 | 1 | 0.80 |

| Cerebral Palsy Module Scales Child Self-report | |||||

| Daily Activities | 60 | 9 | 66 | 1 | 0.93 |

| School Activities | 60 | 4 | 67 | 1 | 0.83 |

| Movement and Balance | 60 | 5 | 57 | 1 | 0.80 |

| Pain and Hurt | 60 | 4 | 71 | 1 | 0.85 |

| Fatigue | 60 | 4 | 50 | 1 | 0.60 |

| Eating Activities | 60 | 5 | 58 | 1 | 0.75 |

| Speech and Communication | 60 | 4 | 47 | 2 | 0.63 |

| Parent Proxy-report | |||||

| Daily Activities | 125 | 9 | 73 | 1 | 0.95 |

| School Activities | 125 | 4 | 78 | 1 | 0.91 |

| Movement and Balance | 125 | 5 | 59 | 1 | 0.83 |

| Pain and Hurt | 125 | 4 | 74 | 1 | 0.87 |

| Fatigue | 125 | 4 | 76 | 1 | 0.89 |

| Eating Activities | 125 | 5 | 71 | 1 | 0.88 |

| Speech and Communication | 125 | 4 | 84 | 1 | 0.93 |

| Items, n | CwCP, n | Mean (SD) | Healthy, n | Mean (SD) | Difference | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Proxy-report | |||||||

| Total Score | 23 | 125 | 63.8 (18.6) | 121 | 86.5 (9.3) | 22.69 ** | 2.44 |

| Physical Functioning | 8 | 125 | 55.6 (28.7) | 121 | 90.5 (10.3) | 34.87 ** | 3.37 |

| Psychosocial Health | 15 | 125 | 68.5 (17.3) | 121 | 84.2 (10.4) | 15.70 ** | 1.51 |

| Emotional Functioning | 5 | 125 | 69.8 (19.6) | 121 | 76.9 (14) | 7.14 * | 0.51 |

| Social Functioning | 5 | 125 | 67.8 (19.9) | 121 | 90.5 (11.9) | 22.69 ** | 1.91 |

| School Functioning | 5 | 114 | 66.9 (25.3) | 115 | 85.7 (14.2) | 18.84 ** | 1.32 |

| Child Self-report | |||||||

| Total Score | 23 | 60 | 71.8 (14.2) | 88 | 83.1 (9) | 11.31 ** | 1.26 |

| Physical Functioning | 8 | 60 | 68.4 (23.2) | 88 | 86.8 (9.4) | 18.37 ** | 1.95 |

| Psychosocial Health | 15 | 60 | 73.7 (14.5) | 88 | 81.1 (10.2) | 7.45 ** | 0.73 |

| Emotional Functioning | 5 | 60 | 72.1 (19.1) | 88 | 72.6 (15.7) | 0.50 | 0.32 |

| Social Functioning | 5 | 60 | 74.8 (17.5) | 88 | 88.7 (11.6) | 13.87 ** | 1.20 |

| School Functioning | 5 | 59 | 73.7 (18.6) | 88 | 82.1 (13.5) | 8.36 * | 0.62 |

| (a) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMFCS | ||||||||

| CPM | Level I | Level II | Level III | Level IV | Level V | p | df | F |

| Mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Child Self-report | n = 33 | n = 12 | n = 7 | n = 5 | n = 3 | |||

| Daily Activities | 85.1 (23.4) | 69 (29.1) | 46 (23.3) | 11.6 (9.7) | 10.2 (17.6) | <0.001 | 4.59 | 17.23 |

| School Activities | 86.7 (22.6) | 87.5 (19.4) | 72.3 (27.9) | 46.3 (28.5) | 25 (43.3) | <0.001 | 4.59 | 7.39 |

| Movement and Balance | 83.6 (17.3) | 82.1 (18.4) | 53.6 (23.4) | 24 (22.2) | 41.7 (27.5) | <0.001 | 4.59 | 15.29 |

| Pain and Hurt | 86 (20.6) | 75.5 (29.4) | 83.9 (20) | 81.3 (25.8) | 66.7 (19.1) | NS | 4.59 | 0.84 |

| Fatigue | 74.4 (20.9) | 70.3 (24.6) | 89.3 (12.9) | 63.8 (10.3) | 72.9 (13) | NS | 4.59 | 1.43 |

| Eating Activities | 95.5 (9.4) | 93.8 (12.5) | 77.7 (34.2) | 81.3 (17.7) | 66.7 (57.7) | NS | 4.59 | 2.98 |

| Speech and Communication | 92.2 (11.4) | 83.9 (19.5) | 82.1 (24.6) | 81.3 (25.8) | 87.5 (12.5) | NS | 4.59 | 1.17 |

| Parent Proxy-report | n = 57 | n = 25 | n = 14 | n = 19 | n = 10 | |||

| Daily Activities | 67 (30.3) | 46.2 (28) | 29.7 (23.4) | 6.4 (14.3) | 4.8 (10.2) | <0.001 | 4.124 | 27.55 |

| * School Activities | 80.8 (23.6) | 60.4 (27.8) | 57.8 (35.9) | 23.4 (28.8) | 8.9 (23.6) | <0.001 | 4.89 | 18.64 |

| Movement and Balance | 71 (21) | 61.4 (20.3) | 38.9 (21.3) | 19.5 (23.9) | 18 (18.7) | <0.001 | 4.124 | 31.42 |

| Pain and Hurt | 85.5 (16.7) | 82.5 (25.3) | 88 (14.6) | 71.7 (28.7) | 51.9 (27.3) | <0.001 | 4.124 | 6.51 |

| Fatigue | 75.9 (22) | 61.3 (29) | 75.5 (24.3) | 61.5 (32.2) | 54.4 (36.9) | 0.03 | 4.124 | 2.79 |

| Eating Activities | 90.2 (17.2) | 79.8 (26.5) | 82.6 (17.9) | 44.1 (37.3) | 30 (42.6) | <0.001 | 4.124 | 20.12 |

| * Speech and Communication | 86.6 (17.9) | 70.5 (34) | 84.4 (24.1) | 43.8 (38.2) | 44.6 (45.6) | <0.001 | 4.89 | 7.66 |

| (b) | ||||||||

| MACS | ||||||||

| CPM | Level I | Level II | Level III | Level IV | Level V | p | df | F |

| Mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Child Self-report | n = 22 | n = 27 | n = 5 | n = 5 | ||||

| Daily Activities | 83.6 (27.9) | 68.6 (29) | 52.2 (36.6) | 18.9 (27.7) | <0.001 | 3.58 | 7.32 | |

| School Activities | 90.3 (22.4) | 80.8 (20.9) | 71.3 (28.2) | 40 (42.8) | 0 | 3.58 | 6.10 | |

| Movement and Balance | 81.4 (20.4) | 77.6 (17.1) | 60 (36.2) | 33 (40.3) | <0.001 | 3.58 | 7.14 | |

| Pain and Hurt | 82.7 (27.5) | 84 (19.8) | 63.8 (17.9) | 93.8 (8.8) | NS | 3.58 | 1.62 | |

| Fatigue | 81.3 (18.9) | 69.7 (21.3) | 71.3 (22.4) | 73.8 (20.9) | NS | 3.58 | 1.34 | |

| Eating Activities | 95.5 (11.9) | 91.9 (12.4) | 82.5 (39.1) | 86.3 (19) | NS | 3.58 | 1.11 | |

| Speech and Communication | 94.3 (12) | 85.7 (18.3) | 81.3 (15.9) | 85 (22.4) | NS | 3.58 | 1.61 | |

| Parent Proxy-report | n = 32 | n = 33 | n = 8 | n = 11 | n = 6 | |||

| Daily Activities | 75 (25) | 54.8 (30.7) | 36.1 (31.7) | 10.4 (18) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | 4.89 | 1.36 |

| * School Activities | 60.4 (22.3) | 62.9 (29.2) | 49.2 (33.7) | 27.3 (28.5) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | 4.89 | 1.37 |

| Movement and Balance | 72.8 (21.3) | 61.1 (21.3) | 48.1 (32.3) | 22.3 (26.6) | 7.5 (8.8) | <0.001 | 4.89 | 18.17 |

| Pain and Hurt | 84.6 (21.8) | 79.2 (20.2) | 72.7 (23.1) | 84.1 (20) | 60.4 (29) | NS | 4.89 | 1.93 |

| Fatigue | 79.9 (20) | 59.9 (25.7) | 62.5 (28.2) | 73.9 (32.5) | 40.6 (37.6) | 0 | 4.89 | 4.43 |

| Eating Activities | 92.6 (14.8) | 80.7 (27.5) | 78.9 (24.1) | 59.7 (36.1) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | 4.89 | 20.84 |

| * Speech and Communication | 89.1 (15.2) | 81.1 (26.1) | 65.6 (38.7) | 42.6 (33.5) | 18.6 (29.3) | <0.001 | 4.89 | 14.93 |

| Children | Parents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Core Scales | n | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t-test | df | p |

| Total Score | 60 | 71.7 (14.3) | 65.7 (16.6) | −3.77 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Physical Functioning | 60 | 68.2 (23.4) | 61.3 (26.6) | −2.66 | 59 | 0.010 |

| Psychosocial Health | 60 | 73.6 (14.6) | 68.1 (15.3) | −2.95 | 59 | 0.005 |

| Emotional Functioning | 60 | 72.1 (19.1) | 67.8 (19.6) | −1.88 | 59 | 0.065 |

| Social Functioning | 60 | 74.8 (17.5) | 66.2 (17.6) | −3.67 | 59 | 0.001 |

| School Functioning | 59 | 74 (18.7) | 70.4 (19.8) | −1.39 | 57 | 0.171 |

| Children | Parents | |||||

| Cerebral Palsy Module Scales | n | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t-test | df | p |

| Daily Activities | 60 | 67.5 (34.4) | 63 (32.3) | 1.84 | 59 | 0.070 |

| School Activities | 60 | 78.8 (28.9) | 71.2 (30.5) | 2.41 | 59 | 0.019 |

| Movement and Balance | 60 | 72.8 (26.8) | 60.8 (26.3) | 4.70 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Pain and Hurt | 60 | 82.3 (22.8) | 79.2 (21.5) | 1.62 | 59 | 0.110 |

| Fatigue | 60 | 74.4 (20.5) | 66.2 (23.9) | 3.05 | 59 | 0.003 |

| Eating Activities | 60 | 90.4 (20.1) | 88.1 (22.2) | 1.03 | 59 | 0.306 |

| Speech and Communication | 60 | 88.2 (16.6) | 84.9 (19.6) | 1.17 | 59 | 0.247 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pedrinelli, I.; Biagi, S.; Romeo, D.M.; Musto, E.; Fagiani, V.; Lanza, M.; Guastafierro, E.; Colombo, A.; Giordano, A.; Montomoli, C.; et al. Construct Validity and Internal Consistency of the Italian Version of the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scale and PedsQLTM 3.0 Cerebral Palsy Module. Children 2025, 12, 749. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060749

Pedrinelli I, Biagi S, Romeo DM, Musto E, Fagiani V, Lanza M, Guastafierro E, Colombo A, Giordano A, Montomoli C, et al. Construct Validity and Internal Consistency of the Italian Version of the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scale and PedsQLTM 3.0 Cerebral Palsy Module. Children. 2025; 12(6):749. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060749

Chicago/Turabian StylePedrinelli, Ilaria, Sofia Biagi, Domenico Marco Romeo, Elisa Musto, Valeria Fagiani, Martina Lanza, Erika Guastafierro, Alice Colombo, Andrea Giordano, Cristina Montomoli, and et al. 2025. "Construct Validity and Internal Consistency of the Italian Version of the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scale and PedsQLTM 3.0 Cerebral Palsy Module" Children 12, no. 6: 749. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060749

APA StylePedrinelli, I., Biagi, S., Romeo, D. M., Musto, E., Fagiani, V., Lanza, M., Guastafierro, E., Colombo, A., Giordano, A., Montomoli, C., Rezzani, C., Casalino, T., Mercuri, E., Riva, D., Leonardi, M., Baranello, G., & Pagliano, E. (2025). Construct Validity and Internal Consistency of the Italian Version of the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scale and PedsQLTM 3.0 Cerebral Palsy Module. Children, 12(6), 749. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060749