Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Illness: The Role of Depression, Nonproductive Thoughts, and Problematic Internet Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What kind of relationship can be found between satisfaction with life and its relationship with nonproductive thoughts, problematic internet use and illness perception?

- What is the association of nonproductive thoughts with depression, problematic internet use and different aspects of illness perception?

- What kind of connection exists between depression and psychological well-being, particularly in terms of illness-related subjective suffering and illness burden?

- Mapping the impact of disease burden on life satisfaction, mental health and psychosocial adjustment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Data Collection

- Age between 10 and 18 years;

- Diagnosis of a chronic illness requiring long-term management and regular clinical follow-up;

- Sufficient literacy and cognitive ability to complete a psychological test battery independently (as assessed by treating clinicians);

- Parental/guardian consent and child assent to participate;

- Intellectual disability or cognitive impairment that would prevent independent questionnaire completion;

- Severe psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., active psychosis);

- Illiteracy or language barriers preventing comprehension of the test materials.

2.2. Study Instruments

- The Satisfaction With Life Scale [27] measures well-being. It is a 5-item measure designed to assess an individual’s overall cognitive judgment of life satisfaction, distinct from the evaluation of emotional states. Participants indicate their agreement with each statement on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach’s α = 0.74).

- The Cantril Ladder [28] also measures subjective well-being. Participants were presented with an image of a ladder numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top, symbolising the full range of possible life experiences, from the worst possible life (0) to the best possible life (10). Participants were asked to place themselves on the rung that best represented their current life situation. Scores of 4 or below indicated a state of “suffering”, whereas scores of 7 or above reflected “thriving”. Higher placements on the ladder were associated with greater perceived well-being and life satisfaction (Cronbach’s α = 0.86).

- The Nonproductive Thoughts Questionnaire (NPG-K) is a single-factor scale [13] for measuring ruminations and rumination in childhood, with scores ranging from 10 to 30. It is a unidimensional scale aimed at evaluating the tendency for rumination and perseverative negative thinking in children. It includes 10 items, each rated on a 3-point scale: 1 (“not true”), 2 (“sometimes true”), and 3 (“often true”). Higher total scores indicate a greater frequency of nonproductive thoughts. In this study, the internal reliability was strong (Cronbach’s α = 0.84).

- The Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire (PIU-Q) for adolescents, an abridged version [29], assesses attitudes and behaviors related to internet use across three subdomains. Using a 5-point Likert scale, participants express their level of agreement with various statements. The “obsession” subscale captures preoccupation with and fantasising about internet activities, as well as withdrawal symptoms when access is restricted. The “neglect” subscale evaluates the extent to which internet use interferes with daily responsibilities and essential needs. The “control disorder” subscale assesses difficulties in managing internet use. The overall internal consistency for the questionnaire was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.84).

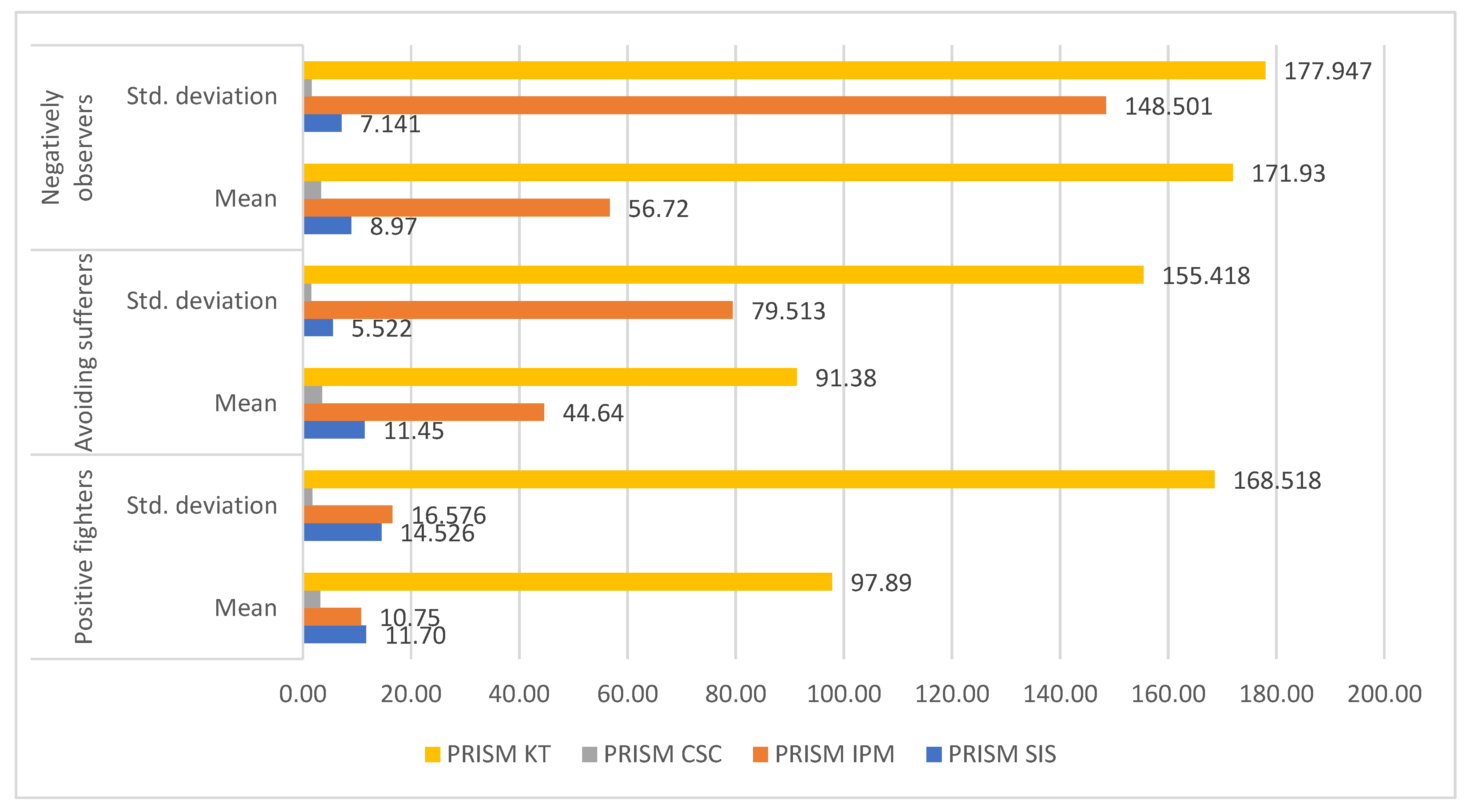

- In the Drawing version of Pictorial Representation of Illness Self-Measure, PRISM-D [30], four subscales of the drawing test developed by the Hungarian working group of the PRISM test were considered: the distance between the yellow circle symbolising self and the circle symbolising illness (SIS), the average area of the circle representing illness 25.12 cm2 (IPM), the number of circles representing youth resources (KSZ), and the total area of the circles representing resources (KT) were compared.

- The Beck Depression Inventory—Shortened Scale (BDI—R) [31], the most reliable measure of depressive symptom severity. It is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that captures emotional and cognitive experiences over a recent time frame. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3, resulting in a total score ranging between 0 and 84. Higher scores indicate greater severity of depressive symptoms. In this study, the BDI demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

- The Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale (IIRS) [32], a measure of “illness burden” as a means of assessing the impact of chronic illness and its treatment on different aspects of life is a 13-item self-report tool developed to assess the degree to which chronic illness and its treatment interfere with areas of life important to quality of life. Although initially intended for individuals coping with severe and life-threatening conditions, it is also applicable to those with less severe health issues. Respondents rate the impact of illness on various domains using a 7-point scale, from 1 (“not very much”) to 7 (“very much”), with higher scores indicating greater perceived disruption. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s α = 0.86).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Relationship Between Satisfaction with Life, Nonproductive Thoughts, Problematic Internet Use and Negative Aspects of Illness Experience

3.3. Relationship Between Nonproductive Thoughts, Depression and Problematic Internet Use

3.4. Relationship Between Depression, Satisfaction with Life and Burden of Disease

3.5. Characteristics of Patient Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with life | Correlation Coefficient | 1.000 | −0.289 ** | −0.201 ** | −0.253 ** | −0.121 | −0.035 | −0.123 | 0.105 | 0.142 * | −0.367 ** | 0.088 | 0.054 | 0.129 | 0.026 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.083 | 0.617 | 0.082 | 0.134 | 0.042 | 0.000 | 0.207 | 0.442 | 0.064 | 0.705 | ||

| Nonproductive thoughts | Correlation Coefficient | −0.289 ** | 1.000 | 0.185 ** | 0.124 | 0.249 ** | −0.115 | 0.270 ** | −0.055 | −0.090 | 0.491 ** | −0.063 | −0.043 | −0.054 | −0.039 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.077 | 0.000 | 0.103 | 0.000 | 0.433 | 0.204 | 0.000 | 0.365 | 0.536 | 0.439 | 0.577 | ||

| Problematic internet use—obsession | Correlation Coefficient | −0.201 ** | 0.185 ** | 1.000 | 0.378 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.002 | 0.061 | −0.147 * | −0.017 | 0.291 ** | 0.055 | 0.089 | 0.073 | 0.054 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.977 | 0.388 | 0.036 | 0.814 | 0.000 | 0.433 | 0.203 | 0.295 | 0.442 | ||

| Problematic internet use—neglect | Correlation Coefficient | −0.253 ** | 0.124 | 0.378 ** | 1.000 | 0.325 ** | 0.102 | 0.103 | 0.078 | 0.131 | 0.262 ** | −0.115 | −0.105 | −0.127 | −0.096 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.077 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.149 | 0.149 | 0.270 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.101 | 0.131 | 0.068 | 0.172 | ||

| Problematic internet use—control | Correlation Coefficient | −0.121 | 0.249 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.325 ** | 1.000 | 0.010 | 0.057 | 0.009 | −0.006 | 0.227 ** | −0.071 | −0.076 | −0.090 | −0.072 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.083 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.883 | 0.425 | 0.898 | 0.936 | 0.001 | 0.308 | 0.275 | 0.198 | 0.305 | ||

| PRISM—subjective suffering caused by illness | Correlation Coefficient | −0.035 | −0.115 | 0.002 | 0.102 | 0.010 | 1.000 | 0.392 ** | 0.208 ** | 0.315 ** | −0.075 | −0.058 | −0.146 * | −0.151 * | −0.101 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.617 | 0.103 | 0.977 | 0.149 | 0.883 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.288 | 0.412 | 0.037 | 0.031 | 0.152 | ||

| PRISM—Disease circle size | Correlation Coefficient | −0.123 | 0.270 ** | 0.061 | 0.103 | 0.057 | 0.392 ** | 1.000 | 0.296 ** | 0.368 ** | 0.299 ** | −0.203 ** | −0.242 ** | −0.301 ** | −0.232 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.388 | 0.149 | 0.425 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | ||

| N | 201 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 201 | 201 | 201 | 201 | 200 | 201 | 201 | 201 | 201 | |

| PRISM—number of rounds | Correlation Coefficient | 0.105 | −0.055 | −0.147 * | 0.078 | 0.009 | 0.208 ** | 0.296 ** | 1.000 | 0.469 ** | −0.007 | −0.009 | −0.033 | −0.053 | 0.000 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.134 | 0.433 | 0.036 | 0.270 | 0.898 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.926 | 0.896 | 0.638 | 0.453 | 0.997 | ||

| PRISM—area of circles | Correlation Coefficient | 0.142 * | −0.090 | −0.017 | 0.131 | −0.006 | 0.315 ** | 0.368 ** | 0.469 ** | 1.000 | −0.051 | −0.043 | −0.148 * | −0.151 * | −0.111 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.042 | 0.204 | 0.814 | 0.063 | 0.936 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.472 | 0.538 | 0.035 | 0.032 | 0.113 | ||

| depression | Correlation Coefficient | −0.367 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.291 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.227 ** | −0.075 | 0.299 ** | −0.007 | −0.051 | 1.000 | −0.134 | −0.083 | −0.196 ** | −0.084 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.288 | 0.000 | 0.926 | 0.472 | 0.055 | 0.234 | 0.005 | 0.230 | ||

| disease burden—all | Correlation Coefficient | 0.088 | −0.063 | 0.055 | −0.115 | −0.071 | −0.058 | −0.203 ** | −0.009 | −0.043 | −0.134 | 1.000 | 0.924 ** | 0.906 ** | 0.929 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.207 | 0.365 | 0.433 | 0.101 | 0.308 | 0.412 | 0.004 | 0.896 | 0.538 | 0.055 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| disease burden—relationships and personal development | Correlation Coefficient | 0.054 | −0.043 | 0.089 | −0.105 | −0.076 | −0.146 * | −0.242 ** | −0.033 | −0.148 * | −0.083 | 0.924 ** | 1.000 | 0.919 ** | 0.933 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.442 | 0.536 | 0.203 | 0.131 | 0.275 | 0.037 | 0.001 | 0.638 | 0.035 | 0.234 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| disease burden—intimacy | Correlation Coefficient | 0.129 | −0.054 | 0.073 | −0.127 | −0.090 | −0.151 * | −0.301 ** | −0.053 | −0.151 * | −0.196 ** | 0.906 ** | 0.919 ** | 1.000 | 0.896 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.064 | 0.439 | 0.295 | 0.068 | 0.198 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 0.453 | 0.032 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| disease herd—device | Correlation Coefficient | 0.026 | −0.039 | 0.054 | −0.096 | −0.072 | −0.101 | −0.232 ** | 0.000 | −0.111 | −0.084 | 0.929 ** | 0.933 ** | 0.896 ** | 1.000 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.705 | 0.577 | 0.442 | 0.172 | 0.305 | 0.152 | 0.001 | 0.997 | 0.113 | 0.230 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

References

- Gerontoukou, E.-I.; Michaelidoy, S.; Rekleiti, M.; Saridi, M.; Souliotis, K. Investigation of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Chronic Diseases. Health Psychol. Res. 2015, 3, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wilder, L.; Pype, P.; Mertens, F.; Rammant, E.; Clays, E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Boeckxstaens, P.; De Smedt, D. Living with a Chronic Disease: Insights from Patients with a Low Socioeconomic Status. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Mateo, D.; Lavín-Pérez, A.M.; Peñacoba, C.; Del Coso, J.; Leyton-Román, M.; Luque-Casado, A.; Gasque, P.; Fernández-del-Olmo, M.Á.; Amado-Alonso, D. Key Factors Associated with Adherence to Physical Exercise in Patients with Chronic Diseases and Older Adults: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Bury, M. Living with Chronic Illness: The Experience of Patients and Their Families; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-040-12244-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vainauskienė, V.; Vaitkienė, R. Enablers of Patient Knowledge Empowerment for Self-Management of Chronic Disease: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Fardell, J.; Wakefield, C.E.; Marshall, G.M.; Bell, J.C.; Nassar, N.; Lingam, R. School Academic Performance of Children Hospitalised with a Chronic Condition. Arch. Dis. Child. 2022, 107, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J. Life Satisfaction and Affect: Why Do These SWB Measures Correlate Differently with Material Goods and Freedom? Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2025, 16, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golics, C.J.; Basra, M.K.A.; Finlay, A.Y.; Salek, S. The Impact of Disease on Family Members: A Critical Aspect of Medical Care. J. R. Soc. Med. 2013, 106, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megari, K. Quality of Life in Chronic Disease Patients. Health Psychol. Res. 2013, 1, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López León, A.; Carreño Moreno, S.; Arias-Rojas, M. Relationship Between Quality of Life of Children with Cancer and Caregiving Competence of Main Family Caregivers. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 38, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, C.K.; Elliott, A.J.; Ganiban, J.; Herbstman, J.; Hunt, K.; Forrest, C.B.; Camargo, C.A.; on behalf of program collaborators for Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes. General Health and Life Satisfaction in Children with Chronic Illness. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20182988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Jain, A.; Chaudhary, J.; Gautam, M.; Gaur, M.; Grover, S. Concept of Mental Health and Mental Well-Being, It’s Determinants and Coping Strategies. Indian J. Psychiatry 2024, 66, S231–S244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsel, N.; Mónok, K.; Szabó, E.; Morgan, A.; Reinhardt, M.; Urbán, R.; Demetrovics, Z.; Kökönyei, G. Nonproductive Thoughts Questionnaire for Children—Hungarian Version. 2019. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft74014-000 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Sijtsema, J.J.; Zeelenberg, M.; Lindenberg, S.M. Regret, Self-Regulatory Abilities, and Well-Being: Their Intricate Relationships. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 1189–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshakhsi, S.; Chemnad, K.; Almourad, M.B.; Altuwairiqi, M.; McAlaney, J.; Ali, R. Problematic Internet Usage: The Impact of Objectively Recorded and Categorized Usage Time, Emotional Intelligence Components and Subjective Happiness about Usage. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, W.; Cai, H.; Wu, S.; Zhang, L.; Feng, K.-X.; Li, Y.-C.; Liu, H.-Z.; Du, X.; Zeng, Z.-T.; Lu, C.-M.; et al. Internet Addiction and Its Association with Quality of Life in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: A Network Perspective. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, A.E.; Moulds, M.L.; Werner-Seidler, A.; Sharrock, M.; Popovic, B.; Newby, J.M. Understanding the Experience of Rumination and Worry: A Descriptive Qualitative Survey Study. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 61, 929–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicol, M.L.; Thorsteinsson, E.B. Internet Addiction, Psychological Distress, and Coping Responses Among Adolescents and Adults. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, M.; Nešić, M. Association of Internet Addiction with Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and the Quality of Sleep: Mediation Analysis Approach in Serbian Medical Students. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2022, 3, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Dunn, M.J.; Rodriguez, E.M. Coping with Chronic Illness in Childhood and Adolescence. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 455–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remes, O.; Mendes, J.F.; Templeton, P. Biological, Psychological, and Social Determinants of Depression: A Review of Recent Literature. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piko, B.F. Adolescent Life Satisfaction: Association with Psychological, School-Related, Religious and Socially Supportive Factors. Children 2023, 10, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sav, A.; King, M.A.; Whitty, J.A.; Kendall, E.; McMillan, S.S.; Kelly, F.; Hunter, B.; Wheeler, A.J. Burden of Treatment for Chronic Illness: A Concept Analysis and Review of the Literature. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samwiri Nkambule, E.; Msiska, G. Chronic Illness Experience in the Context of Resource-Limited Settings: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2024, 19, 2378912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, H.; Weinman, J.; Leventhal, E.A.; Phillips, L.A. Health Psychology: The Search for Pathways between Behavior and Health. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 477–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, H.; Phillips, L.A.; Burns, E. The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM): A Dynamic Framework for Understanding Illness Self-Management. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 39, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos, T.; Sallay, V.; Désfalvi, J.; Szabó, T.; Ittzés, A. Az Élettel való Elégedettség Skála magyar változatának (SWLS-H) pszichometriai jellemzői = Psychometric characteristics of the Hungarian version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS-H). Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika 2014, 15, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Due, P.; Eriksson, C.; Torsheim, T.; Potrebny, T.; Välimaa, R.; Suominen, S.; Rasmussen, M.; Currie, C.; Damsgaard, M. Trends in High Life Satisfaction among Adolescents in Five Nordic Countries 2002–2014. Nord. Välfärdsforskning 2019, 4, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetrovics, Z.; Szeredi, B.; Rózsa, S. The Three-Factor Model of Internet Addiction: The Development of the Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchi, S.; Sensky, T. PRISM: Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure: A Brief Nonverbal Measure of Illness Impact and Therapeutic Aid in Psychosomatic Medicine. Psychosomatics 1999, 40, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An Inventory for Measuring Depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devins, G.M. Using the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale to Understand Health-Related Quality of Life in Chronic Disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michl, L.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Shepherd, K.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Rumination as a Mechanism Linking Stressful Life Events to Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: Longitudinal Evidence in Early Adolescents and Adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2013, 122, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggeri, K.; Garcia-Garzon, E.; Maguire, Á.; Matz, S.; Huppert, F.A. Well-Being Is More than Happiness and Life Satisfaction: A Multidimensional Analysis of 21 Countries. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Mao, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; He, J.; Fan, X. Associations Between Problematic Internet Use and Mental Health Outcomes of Students: A Meta-Analytic Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2023, 8, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Lopez-Fernandez, O. Internet Addiction and Problematic Internet Use: A Systematic Review of Clinical Research. World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.; Ofosu, A.; Preyde, M. Adolescents Hospitalized for Psychiatric Illness: Caregiver Perspectives on Challenges. Adolescents 2023, 3, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dertli, S.; Aydin Yilmaz, A.S.; Gunay, U. Care Burden, Perceived Social Support, Coping Attitudes and Life Satisfaction of Mothers with Children with Cerebral Palsy. Child. Care Health Dev. 2024, 50, e13297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardi, A.; Gigantesco, A.; Tarolla, E.; Stoppioni, V.; Cerbo, R.; Cremonte, M.; Alessandri, G.; Lega, I.; Nardocci, F. Parental Burden and Its Correlates in Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Multicentre Study with Two Comparison Groups. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2018, 14, 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, F.; Rega, V.; Boursier, V. Problematic Internet Use and Emotional Dysregulation Among Young People: A Literature Review. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2021, 18, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim Demirdöğen, E.; Akinci, M.A.; Bozkurt, A.; Bayraktutan, B.; Turan, B.; Aydoğdu, S.; Ucuz, İ.; Abanoz, E.; Yitik Tonkaz, G.; Çakir, A.; et al. Social Media Addiction, Escapism and Coping Strategies Are Associated with the Problematic Internet Use of Adolescents in Türkiye: A Multi-Center Study. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1355759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacci, P.; Tobia, V.; Marra, V.; Desideri, L.; Baiocco, R.; Ottaviani, C. Rumination and Emotional Profile in Children with Specific Learning Disorders and Their Parents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, S.B.; Knisely, J.S.; Schubert, C.M.; Green, J.D.; Ameringer, S. The Effect of an Animal-Assisted Intervention on Anxiety and Pain in Hospitalized Children. Anthrozoos 2015, 28, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlack, R.; Peerenboom, N.; Neuperdt, L.; Junker, S.; Beyer, A.-K. The Effects of Mental Health Problems in Childhood and Adolescence in Young Adults: Results of the KiGGS Cohort. J. Health Monit. 2021, 6, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohan, J.M.; Verma, T. Psychological Considerations in Pediatric Chronic Illness: Case Examples. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.G.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Erskine, H.E.; Roberts, J.; Rahman, A. Childhood Mental and Developmental Disorders. In Mental, Neurological, and Substance Use Disorders: Disease Control Priorities, 3rd ed.; Patel, V., Chisholm, D., Dua, T., Laxminarayan, R., Medina-Mora, M.E., Eds.; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 4, ISBN 978-1-4648-0426-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride, J.B.; Anglin, D.M.; Colman, I.; Dykxhoorn, J.; Jones, P.B.; Patalay, P.; Pitman, A.; Soneson, E.; Steare, T.; Wright, T.; et al. The Social Determinants of Mental Health and Disorder: Evidence, Prevention and Recommendations. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupferberg, A.; Hasler, G. The Social Cost of Depression: Investigating the Impact of Impaired Social Emotion Regulation, Social Cognition, and Interpersonal Behavior on Social Functioning. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2023, 14, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akif, A.; Qusar, M.M.A.S.; Islam, M.R. The Impact of Chronic Diseases on Mental Health: An Overview and Recommendations for Care Programs. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2024, 26, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronister, J.; Fitzgerald, S.; Chou, C.-C. The Meaning of Social Support for Persons with Serious Mental Illness: Family Member Perspective. Rehabil. Psychol. 2021, 66, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beevers, C.G.; Mullarkey, M.C.; Dainer-Best, J.; Stewart, R.A.; Labrada, J.; Allen, J.J.B.; McGeary, J.E.; Shumake, J. Association between Negative Cognitive Bias and Depression: A Symptom-Level Approach. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koval, P.; Kuppens, P.; Allen, N.B.; Sheeber, L. Getting Stuck in Depression: The Roles of Rumination and Emotional Inertia. Cogn. Emot. 2012, 26, 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğrusever, C.; Bilgin, M. From Family Social Support to Problematic Internet Use: A Serial Mediation Model of Hostility and Depression. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakshine, V.S.; Thute, P.; Khatib, M.N.; Sarkar, B. Increased Screen Time as a Cause of Declining Physical, Psychological Health, and Sleep Patterns: A Literary Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubair, U.; Khan, M.K.; Albashari, M. Link between Excessive Social Media Use and Psychiatric Disorders. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, F.C.; Erwin, S.; Burnell, K.; Jackson, J.; Storch, M.; Nicholas, J.; Zucker, N. Intervening on Social Comparisons on Social Media: Electronic Daily Diary Pilot Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2023, 10, e42024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Hong, K.; Bergquist, K.; Sinha, R. Gender Differences in Response to Emotional Stress: An Assessment Across Subjective, Behavioral, and Physiological Domains and Relations to Alcohol Craving. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2008, 32, 1242–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robichaud, M.; Dugas, M.J.; Conway, M. Gender Differences in Worry and Associated Cognitive-Behavioral Variables. J. Anxiety Disord. 2003, 17, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhane-Medina, N.Z.; Luque, B.; Tabernero, C.; Castillo-Mayén, R. Factors Associated with Gender and Sex Differences in Anxiety Prevalence and Comorbidity: A Systematic Review. Sci. Prog. 2022, 105, 00368504221135469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Chen, L.; Xie, H.; Wang, C.; Duan, R.; Chen, D.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Liu, L. Influence of Parental Attitudes and Coping Styles on Mental Health during Online Teaching in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubow, E.F.; Boxer, P.; Huesmann, L.R. Long-Term Effects of Parents’ Education on Children’s Educational and Occupational Success: Mediation by Family Interactions, Child Aggression, and Teenage Aspirations. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2009, 55, 224–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Supporting the Parents of Young Children; Breiner, H.; Ford, M.; Gadsden, V.L. Parenting Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices. In Parenting Matters: Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0–8; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, K.D. Personality, Negative Interactions, and Mental Health. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2008, 82, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauritz, P.J.; Bolling, M.; Duipmans, J.C.; Hagedoorn, M. The Relationship between Quality of Life and Coping Strategies of Children with EB and Their Parents. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrylkevych, V.; Podkorytova, L.; Danylchuk, L.; Romanovska, L.; Kravchyna, T.; Chovgan, O. Psychological Correction of Parents’ Attitude to Their Children with Special Educational Needs by Means of Art Therapy. BRAIN 2021, 12, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogh, Z.É.; Erdei, I.; Kovács, K.E.; Nagy, B.E. Psychological Effects of Animal-Assisted Programs Among Children with Special Needs—Experiences From a Systematic Review. J. Posit. Psychol. Wellbeing 2024, 8, 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.; Ali, M.; Ali, A.H.; El-Rahman, M.A.; Hincal, E.; Neamah, H.A. Mathematical Analysis with Control of Liver Cirrhosis Causing from HBV by Taking Early Detection Measures and Chemotherapy Treatment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghrabat, M.j.J.; Mohialdin, S.H.; Abdulrahman, L.Q.; Al-Yoonus, M.H.; Abduljabbar, Z.A.; Honi, D.G.; Nyangaresi, V.O.; Abduljaleel, I.Q.; Neamah, H.A. Utilizing Machine Learning for the Early Detection of Coronary Heart Disease. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 17363–17375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragó, T.; Gácsi, M.; Korcsok, B.; Miklósi, Á. Why Is a Dog-Behaviour-Inspired Social Robot Not a Doggy-Robot? Interact. Stud. 2014, 15, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clusters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Fighters | Avoiding Sufferers | Negative Observers | |

| IIRS_relationships | −0.03038 | −0.68284 | 2.10529 |

| IIRS_intimacy | −0.03066 | −0.63105 | 1.96410 |

| IIRS_instrument | −0.01801 | −0.64992 | 1.95025 |

| NPG | −0.43886 | 0.60906 | 0.66958 |

| BDI-R | −0.46333 | 0.57115 | 0.91273 |

| SWLS | 0.50984 | −0.73287 | −0.72073 |

| Cantril ladder | 0.42707 | −0.61695 | −0.65843 |

| Clusters | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Fighters | Avoiding Sufferers | Negative Observers | |||

| boy | N | 62 | 22 | 14 | 98 |

| Row% | 63.3% | 22.4% | 14.3% | 100.0% | |

| Adjusted Residual | 1.3 | −2.4 | 1.6 | ||

| Girl | N | 59 | 41 | 8 | 108 |

| Row % | 54.6% | 38.0% | 7.4% | 100.0% | |

| Adjusted Residual | −1.3 | 2.4 | −1.6 | ||

| Total | N | 121 | 63 | 22 | 206 |

| Row % | 58.7% | 30.6% | 10.7% | 100.0% | |

| Clusters | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Fighters | Avoiding Sufferers | Negative Observers | ||||

| father’s educational level | primary | N | 7 | 4 | 4 | 15 |

| Row % | 46.7% | 26.7% | 26.7% | 100.0% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | −1.1 | −0.2 | 1.9 | |||

| secondary | N | 51 | 16 | 14 | 81 | |

| Row % | 63.0% | 19.8% | 17.3% | 100.0% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | 0.7 | −2.3 | 2.2 | |||

| tertiary | N | 57 | 35 | 4 | 96 | |

| Row % | 59.4% | 36.5% | 4.2% | 100.0% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | −0.1 | 2.4 | −3.2 | |||

| Total | N | 115 | 55 | 22 | 192 | |

| Sor% | 59.9% | 28.6% | 11.5% | 100.0% | ||

| mother’s education | primary | N | 9 | 3 | 6 | 18 |

| Row % | 50.0% | 16.7% | 33.3% | 100.0% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | −0.9 | −1.3 | 3.3 | |||

| secondary | N | 56 | 32 | 9 | 97 | |

| Row % | 57.7% | 33.0% | 9.3% | 100.0% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | −0.7 | 1.1 | −0.6 | |||

| tertiary | N | 49 | 21 | 5 | 75 | |

| Row % | 65.3% | 28.0% | 6.7% | 100.0% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | 1.2 | −0.4 | −1.4 | |||

| Total | N | 114 | 56 | 20 | 190 | |

| Row % | 60.0% | 29.5% | 10.5% | 100.0% | ||

| Clusters | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Fighters | Avoiding Sufferers | Negative Observers | ||||

| coexistence | with mother and father | N | 21 | 9 | 6 | 36 |

| Row % | 58.3% | 25.0% | 16.7% | 100.0% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | −0.1 | −0.8 | 1.3 | |||

| only with mother/father/other family member | N | 100 | 54 | 16 | 170 | |

| Row % | 58.8% | 31.8% | 9.4% | 100.0% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | 0.1 | 0.8 | −1.3 | |||

| Total | N | 121 | 63 | 22 | 206 | |

| Row % | 58.7% | 30.6% | 10.7% | 100.0% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovács, K.E.; Boris, P.; Nagy, B.E. Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Illness: The Role of Depression, Nonproductive Thoughts, and Problematic Internet Use. Children 2025, 12, 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050657

Kovács KE, Boris P, Nagy BE. Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Illness: The Role of Depression, Nonproductive Thoughts, and Problematic Internet Use. Children. 2025; 12(5):657. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050657

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovács, Karolina Eszter, Péter Boris, and Beáta Erika Nagy. 2025. "Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Illness: The Role of Depression, Nonproductive Thoughts, and Problematic Internet Use" Children 12, no. 5: 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050657

APA StyleKovács, K. E., Boris, P., & Nagy, B. E. (2025). Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Illness: The Role of Depression, Nonproductive Thoughts, and Problematic Internet Use. Children, 12(5), 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050657