Family Support, Communication with Parents, and Adolescent Health Risk Behaviour: A Case of HBSC Study from Bulgaria and Lithuania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristic

3.2. Bivariate Associations

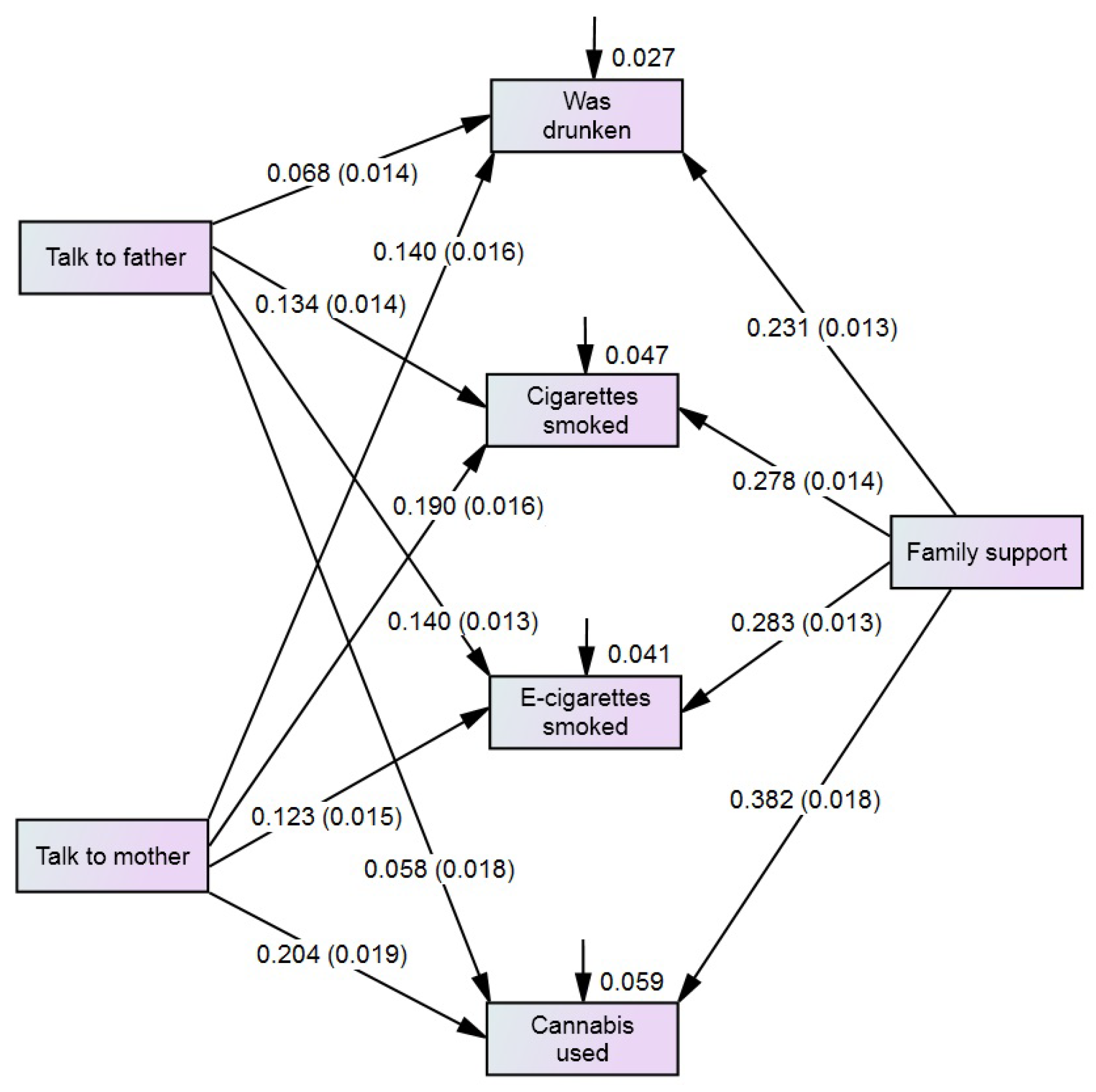

3.3. Multivariate Analysis with SEM Model

3.4. Multi-Group Analysis of Relationships

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sawyer, S.M.; Afifi, R.A.; Bearinger, L.H.; Blakemore, S.J.; Dick, B.; Ezeh, A.C.; Patton, G.C. Adolescence: A foundation for future health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1630–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihić, J.; Skinner, M.; Novak, M.; Ferić, M.; Kranželić, V. The Importance of Family and School Protective Factors in Preventing the Risk Behaviors of Youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaryati, N.P.; Malathum, P. Family Support: A Concept Analysis. Pac. Rim Int. J. 2020, 3, 403–411. [Google Scholar]

- McMorris, B.J.; Catalano, R.F.; Kim, M.J.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Hemphill, S.A. Influence of family factors and supervised alcohol use on adolescent alcohol use and harms: Similarities between youth in different alcohol policy contexts. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2011, 3, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cao, S.; Hu, R. Smoking by family members and friends and electronic-cigarette use in adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2018, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborskis, A.; Kavaliauskienė, A.; Eriksson, C.; Klemera, E.; Dimitrova, E.; Melkumova, M.; Husarova, D. Family Support as Smoking Prevention during Transition from Early to Late Adolescence: A Study in 42 Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 23, 12739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawi, A.M.; Ismail, R.; Ibrahim, F.; Hassan, M.R.; Manaf, M.R.A.; Amit, N.; Ibrahim, N.; Shafurdin, N.S. Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, N.; Tian, L. The Parent-Adolescent Relationship and Risk-Taking Behaviors Among Chinese Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Self-Control. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, N.; Quigg, Z.; Bates, R.; Jones, L.; Ashworth, E.; Gowland, S.; Jones, M. The Contributing Role of Family, School, and Peer Supportive Relationships in Protecting the Mental Wellbeing of Children and Adolescents. Sch. Ment. Health 2022, 14, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, G.; Zhou, D.; Song, P.; Wang, Y.; Bian, G. Prevalences of Parental and Peer Support and Their Independent Associations With Mental Distress and Unhealthy Behaviours in 53 Countries. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheux, A.J.; Widman, L.; Stout, C.D.; Choukas-Bradley, S. Profiles of Early Adolescents’ Health Risk Communication with Parents: Gender Differences and Associations with Health Risk Behavior. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2024, 33, 3651–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criss, M.M.; Smith, A.M.; Morris, A.S.; Liu, C.; Hubbard, R.L. Parents and peers as protective factors among adolescents exposed to neighborhood risk. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, F.; Zaborskis, A.; Tabak, I.; del Carmen Granado Alcón, M.; Zemaitiene, N.; de Roos, S.; Klemera, E. Trends in adolescents’ perceived parental communication across 32 countries in Europe and North America from 2002 to 2010. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolip, P.; Schmidt, B.; World Health Organization; Regional Office for Europe. Gender and Health in Adolescence; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1999; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/108178 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Ball, J.; Grucza, R.; Livingston, M.; Ter Bogt, T.; Currie, C.; de Looze, M. The great decline in adolescent risk behaviours: Unitary trend, separate trends, or cascade? Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 317, 115616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, J.W.; Farhat, T.; Iannotti, R.J.; Simons-Morton, B.G. Parent-child communication and substance use among adolescents: Do father and mother communication play a different role for sons and daughters? Addict. Behav. 2010, 5, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzini, A.B.; Bauer, A.; Maruyama, J.; Simões, R.; Matijasevich, A. Factors associated with risk behaviors in adolescence: A systematic review. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2021, 43, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Heron, J.; Campbell, R.; Hickman, M.; Kipping, R. Adolescent multiple risk behaviours cluster by number of risks rather than distinct risk profiles in the ALSPAC cohort. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, K.E.; Mather, M.; Spring, B.; Kay-Lambkin, F.; Teesson, M.; Newton, N.C. Clustering of multiple risk behaviors among a sample of 18-year-old Australians and associations with mental health outcomes: A Latent Class Analysis. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.H.; Oh, J.W.; Lee, S.; Lee, J. Multiple risk-taking behaviors in Korean adolescents and associated factors: 2020 and 2021 Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2024, 177, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Samdal, O.; Jåstad, A.; Cosma, A.; Nic Gabhainn, S. (Eds.) Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study Protocol: Background, Methodology and Mandatory Items for the 2021/22 Survey; MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow: Glasgow, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- HBSC. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children. Publications. Reports. Available online: https://hbsc.org/publications/reports/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Zaborskis, A.; Kavaliauskienė, A.; Dimitrova, E.; Eriksson, C. Pathways of Adolescent Life Satisfaction Association with Family Support, Structure and Affluence: A Cross-National Comparative Analysis. Medicina 2022, 58, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Širvytė, D. Adolescents’ Risk Behaviour and Its Relationship with Family Social Factors and Peculiarities of Communication with Parents. Doctoral Dissertation, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Regional Office. Situation Analysis of Children and Women in Bulgaria. In UNICEF-Bulgaria Report; UNICEF: UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Regional Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/bulgaria/media/2821/file/BGR-situation-analysis-children-women-bulgaria.pdf.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Charrier, L.; van Dorsselaer, S.; Canale, N.; Baska, T.; Kilibarda, B.; Comoretto, R.I.; Galeotti, T.; Brown, J.; Vieno, A. A Focus on Adolescent Substance Use in Europe, Central Asia and Canada. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children International Report from the 2021/2022 Survey; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; Volume 3, Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/376573 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Powell, S.S.; Farley, G.K.; Werkman, S.; Berkoff, K.A. Psychometric characteristics of Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1990, 55, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čekanavičius, V.; Murauskas, G. Statistika ir Jos Taikymai (Statistics and Its Applications); 3 Knyga; REV UAB BĮ: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2009. (In Lithuanian) [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus. Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables. User’s Guide, 7th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Muller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Meth. Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, Y. RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritsotakis, G.; Psarrou, M.; Vassilaki, M.; Androulaki, Z.; Philalithis, A.E. Gender differences in the prevalence and clustering of multiple health risk behaviours in young adults. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 9, 2098–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Gender differences in health risk behaviour among university students: An international study. Gend. Behav. 2015, 1, 6576–6583. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Procházková, M.; Lu, J.; Riad, A.; Macek, P. Family Related Variables’ Influences on Adolescents’ Health Based on Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Database, an AI-Assisted Scoping Review, and Narrative Synthesis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 871795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, F.M.; Magnusson, J.; Spencer, N.; Morgan, A. Adolescent multiple risk behaviour: An asset approach to the role of family, school and community. J. Public Health 2012, 34, i48–i56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. The Role of Gender in Parenting Styles and Their Effects on Child Development. Notes Educ. Psychol. Public Media 2023, 18, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.; Thomas, T.M.; Sreekumar, S. Gendered parenting and gender role attitude among children. Cult. Psychol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonynienė, J.; Kern, R.M. Individual psychology lifestyles and parenting style in Lithuanian parents of 6- to 12-year-olds. Int. J. Psychol. Biopsychosoc. Approach Tarptautinis Psichilogijos Žurnalas Biopsich. Požiūris 2012, 11, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totkova, Z. Teoria za roditelskia stil v psihologia na razvitieto (Theory of parenting stype in developmental psychology). Psihol. Probl. (Pschol. Res.) 2012, 2, 41–48. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Skeer, M.R.; McCormick, M.C.; Normand, S.L.; Mimiaga, M.J.; Buka, S.L.; Gilman, S.E. Gender differences in the association between family conflict and adolescent substance use disorders. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 2, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderberg, M.; Dahlberg, M. Gender differences among adolescents with substance abuse problems at Maria clinics in Sweden. Nord. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2018, 1, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, B.; Moller, A.C.; Coons, M.J. Multiple health behaviours: Overview and implications. J. Public Health 2012, 34, i3–i10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Groups of Respondents | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | Selected Countries | Bulgaria | Lithuania | ||||||

| Boys and Girls (n = 64,349) | Boys (n = 31,070) | Girls (n = 33,279) | Bulgaria (n = 793) | Lithuania (n = 1137) | Boys (n = 413) | Girls (n = 380) | Boys (n = 592) | Girls (n = 545) | |

| Was drunken | 14.9 | 14.9 | 14.9 | 27.0 | 14.9 *** | 31.7 | 21.8 ** | 14.0 | 15.8 |

| Cigarette smoked | 12.6 | 12.1 | 13.1 *** | 29.9 | 17.8 *** | 29.1 | 30.8 | 18.4 | 16.1 |

| E-cigarette smoked | 18.4 | 17.3 | 19.3 *** | 29.8 | 30.7 | 26.6 | 33.2 * | 30.4 | 31.0 |

| Cannabis used | 5.9 | 6.8 | 5.1 *** | 11.1 | 5.5 *** | 14.5 | 7.4 *** | 6.6 | 4.2 |

| Easy talk to father | 63.6 | 73.1 | 54.7 *** | 73.0 | 59.9 *** | 79.2 | 66.3 *** | 72.0 | 46.8 *** |

| Easy talk to mother | 78.1 | 82.0 | 74.5 *** | 79.3 | 75.9 | 79.7 | 78.8 | 80.9 | 70.5 *** |

| High family support | 53.1 | 57.4 | 49.0 *** | 45.8 | 48.1 | 44.3 | 47.4 | 52.2 | 43.7 ** |

| Risky Behaviour by Family Characteristic | Groups of Respondents | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | Selected Countries | Bulgaria | Lithuania | ||||||

| Boys and Girls (n = 64,349) | Boys (n = 31,070) | Girls (n = 33,279) | Bulgaria (n = 793) | Lithuania (n = 1137) | Boys (n = 413) | Girls (n = 380) | Boys (n = 592) | Girls (n = 545) | |

| Was drunken on: | |||||||||

| Talk to father (difficult vs. easy) | 1.46 *** (1.40; 1.53) | 1.35 *** (1.26; 1.45) | 1.60 *** (1.51; 1.71) | 1.15 (0.81; 1.62) | 1.63 *** (1.17; 2.26) | 1.20 (0.73; 1.98) | 1.31 (0.79; 2.18) | 1.65 * (1.02; 2.69) | 1.60 * (1.00; 2.56) |

| Talk to mother (difficult vs. easy) | 1.65 *** (1.52; 1.73) | 1.61 *** (1.50; 1.74) | 1.69 *** (1.58; 1.80) | 2.34 *** (1.63; 3.36) | 1.49 * (1.04; 2.14) | 2.70 *** (1.65; 4.41) | 2.05 ** (1.19; 3.56) | 1.31 (0.75; 2.29) | 1.61 * (1.00; 2.60) |

| Family support (low vs. high) | 1.74 *** (1.67; 1.82) | 1.61 *** (1.51; 1.71) | 1.90 *** (1.78; 2.02) | 1.99 *** (1.44; 2.76) | 1.46 * (1.04; 2.03) | 2.59 *** (1.66; 4.04) | 1.39 (0.85; 2.28) | 1.21 (0.76; 1.92) | 1.75 * (1.07; 2.84) |

| Cigarette smoked on: | |||||||||

| Talk to father (difficult vs. easy) | 1.78 *** (1.70; 1.86) | 1.62 *** (1.51; 1.74) | 1.93 *** (1.81; 2.06) | 1.35 (0.97; 1.89) | 1.08 (0.79:1.47) | 1.32 (0.79; 2.19) | 1.36 (0.86; 2.14) | 0.97 (0.61; 1.54) | 1.33 (0.84; 2.11) |

| Talk to mother (difficult vs. easy) | 2.00 *** (1.90; 2.10) | 1.95 *** (1.80; 2.11) | 2.02 *** (1.89; 2.16) | 2.51 *** (1.76; 3.58) | 1.40 (0.99; 1.97) | 3.22 *** (1.96; 5.29) | 1.93 * (1.16; 3.21) | 1.17 (0.70; 1.95) | 1.74 * (1.08; 2.79) |

| Family support (low vs. easy) | 2.09 *** (1.99; 2.19) | 1.88 *** (1.76; 2.02) | 2.29 *** (2.14; 2.45) | 1.98 *** (1.45; 2.72) | 1.44 * (1.06; 1.97) | 2.77 *** (1.74; 4.39) | 1.45 (0.93; 2.25) | 1.19 (0.79; 1.81) | 1.94 * (1.19; 3.16) |

| E-cigarette smoked on: | |||||||||

| Talk to father (difficult vs. easy) | 1.67 *** (1.61; 1.74) | 1.52 *** (1.43; 1.62) | 1.77 *** (1.68; 1.87) | 1.49 * (1.06;2.07) | 1.41 * (1.09; 1.82) | 1.34 (0.80; 2.26) | 1.48 (0.95; 2.32) | 1.19 (0.81; 1.75)) | 1.69 ** (1.17; 2.45) |

| Talk to mother (difficult vs. easy) | 1.74 *** (1.66; 1.82) | 1.66 *** (1.54; 1.76) | 1.77 *** (1.67; 1.88) | 1.70 ** (1.19; 2.44) | 1.48 ** (1.11; 1.97) | 2.76 *** (1.67; 4.57) | 1.03 (0.61; 1.74) | 1.39 (0.91; 2.14) | 1.56 * (1.06; 2.30) |

| Family support (low vs. high) | 1.94 *** (1.86; 2.01) | 1.70 *** (1.60; 1.80) | 2.17 *** (2.05; 2.94) | 1.16 (0.85; 1.57) | 1.54 ** (1.19; 1.99) | 1.94 ** (1.23; 3.06) | 0.74 (0.48; 1.14) | 1.29 (0.91; 1.83) | 1.89 ** (1.30; 2.77) |

| Cannabis used on: | |||||||||

| Talk to father (difficult vs. easy) | 1.78 *** (1.67; 1.90) | 1.75 *** (1.59; 1.92) | 2.23 *** (2.01; 2.47) | 0.89 (0.54; 1.48) | 1.64 (0.98; 2.74) | 1.19 (0.62; 2.28) | 0.77 (0.33; 1.81) | 1.48 (0.75; 2.92) | 3.31 *** (1.21;9.05) |

| Talk to mother (difficult vs. easy) | 2.25 *** (2.10; 2.41) | 2.19 *** (1.98; 2.41) | 2.54 *** (2.30; 2.80) | 3.91 *** (2.46; 6.20) | 1.66 (0.97; 2.87) | 4.64 *** (2.59; 8.31) | 3.13 *** (1.42; 6.93) | 1.51 (0.71; 3.19) | 2.27 (0.98; 5.27) |

| Family support (low vs. high) | 2.75 (2.56; 2.96) | 2.60 *** (2.37; 2.85) | 3.26 *** (2.91; 3.66) | 3.46 *** (2.04; 5.87) | 2.57 *** (1.46; 4.56) | 4.81 *** (2.36; 9.78) | 1.99 (0.88; 4.53) | 1.81 (0.93; 3.54) | 8.66 *** (2.01; 37.3) |

| Characteristics | Groups of Respondents | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | Selected Countries | Bulgaria | Lithuania | ||||||

| Boys and Girls (n = 64,349) | Boys (n = 31,070) | Girls (n = 33,279) | Bulgaria (n = 793) | Lithuania (n = 1137) | Boys (n = 413) | Girls (n = 380) | Boys (n = 592) | Girls (n = 545) | |

| Path | Regression weights B (standard errors) | ||||||||

| Was drunken on: | |||||||||

| Talk to father | 0.068 (0.014) *** | 0.021 (0.022) | 0.119 (0.019) *** | −0.149 (0.114) | 0.196 (0.107) | −0.136 (0.129) | 0.005 (0.165) | 0.281 (0.162) | 0.111 (0.154) |

| Talk to mother | 0.140 (0.016) *** | 0.170 (0.024) *** | 0.119 (0.021) *** | 0.456 (0.125) *** | 0.083 (0118) | 0.434 (0.134) *** | 0.351 (0.185) | −0.010 (0.192) | 0.136 (0.153) |

| Family support | 0.231 (0.013) *** | 0.208 (0.019) *** | 0.257 (0.019) *** | 0.312 (0.104) ** | 0.095 (0.105) | 0.548 (0.117) *** | 0.080 (0.154) | 0.032 (0.139) | 0.190 (0.162) |

| Cigarettes smoked on: | |||||||||

| Talk to father | 0.134 (0.014) *** | 0.080 (0.022) *** | 0.180 (0.018) *** | −0.047 (0.112) | −0.101 (0.118) | −0.237 (0.130) | 0.034 (0.159) | −0.085 (0.154) | −0.064 (0.162) |

| Talk to mother | 0.190 (0.016) *** | 0.217 (0.025) *** | 0.171 (0.021) *** | 0.419 (0.125) *** | 0.151 (0.118) | 0.524 (0.137) *** | 0.334 (0.185) | 0.085 (0.174) | 0.204 (0.162) |

| Family support | 0.278 (0.014) *** | 0.252 (0.020) *** | 0.305 (0.020) *** | 0.289 (0.103) ** | 0.193 (0.106) | 0.472 (0.121) *** | 0.080 (0.154) | 0.112 (0.135) | 0.321 (0.171) |

| E-cigarettes smoked on: | |||||||||

| Talk to father | 0.140 (0.013) *** | 0.098 (0.021) *** | 0.163 (0.018) *** | 0.157 (0.109) | 0.087 (0.091) | −0.130 (0.131) | 0.317 (0.154) * | 0.015 (0.136) | 0.166 (0.131) |

| Talk to mother | 0.123 (0.015) *** | 0.140 (0.028) *** | 0.106 (0.020) *** | 0.272 (0.124) | 0.110 (103) | 0.550 (0.148) *** | −0.038 (0.184) | 0.145 (0.154) | 0.081 (0.141) |

| Family support | 0.283 (0.013) | 0.229 (0.018) *** | 0.335 (0.018) *** | −0.021 (0.103) | 0.189 (0.089) * | 0.145 (0.119) | −0.308 (0152) | 0.117 (0.119) | 0.279 (0.137) * |

| Cannabis used on: | |||||||||

| Talk to father | 0.058 (0.018) *** | 0.051 (0.026) * | 0.154 (0.026) *** | −0.457 (0.146) ** | 0.052 (0.147) | −0.397 (0.155) ** | −0.481 (0.261) | 0.092 (0.183) | 0.200 (0.327) |

| Talk to mother | 0.204 (0.019) *** | 0.210 (0.028) *** | 0.211 (0.027) *** | 0.733 (0.152) *** | 0.059 (0.150) | 0.750 (0.148) *** | 0.608 (0.317) | 0.004 (0.201) | 0.040 (0.244) |

| Family support | 0.382 (0.018) *** | 0.386 (0.024) *** | 0.392 (0.028) *** | 0.485 (0.145) ** | 0.392 (0.147) ** | 0.483 (0.151) *** | 0.081 (0.277) | 0.273 (0.172) | 0.782 (0.369) * |

| Variable | Squared multiple correlations (R2) | ||||||||

| Was drunken | 0.027 | 0.020 | 0.036 | 0.064 | 0.020 | 0.112 | 0.019 | 0.017 | 0.028 |

| Cigarettes smoked | 0.047 | 0.035 | 0.059 | 0.067 | 0.014 | 0.104 | 0.026 | 0.004 | 0.039 |

| E-cigarettes smoked | 0.041 | 0.027 | 0.054 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.062 | 0.032 | 0.010 | 0.043 |

| Cannabis used | 0.059 | 0.055 | 0.079 | 0.145 | 0.046 | 0.145 | 0.069 | 0.027 | 0.170 |

| Test to check the equality of regression weights between groups | |||||||||

| Degree of freedom | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | |||||

| Chi-squared | 164.76 | 53.826 | 21.448 | 12.411 | |||||

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.015 | 0.563 | |||||

| Goodness-of-fit characteristics | |||||||||

| Chi-squared/degree of freedom | 16.021; p < 0.001 | 6.002; p < 0.001 | 2.462; p = 0.042 | 1.136; p = 0.480 | |||||

| TLI | 0.986 | 0.911 | 0.905 | 0.981 | |||||

| CFI | 0.974 | 0.942 | 0.912 | 0.975 | |||||

| RMSEA (90% CI) | 0.027 (0.018; 0.036) | 0.052 (0.041; 0.070) | 0.048 (0.024; 0.072) | 0.021 (0.009; 0.032) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dimitrova, E.; Zaborskis, A. Family Support, Communication with Parents, and Adolescent Health Risk Behaviour: A Case of HBSC Study from Bulgaria and Lithuania. Children 2025, 12, 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050654

Dimitrova E, Zaborskis A. Family Support, Communication with Parents, and Adolescent Health Risk Behaviour: A Case of HBSC Study from Bulgaria and Lithuania. Children. 2025; 12(5):654. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050654

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimitrova, Elitsa, and Apolinaras Zaborskis. 2025. "Family Support, Communication with Parents, and Adolescent Health Risk Behaviour: A Case of HBSC Study from Bulgaria and Lithuania" Children 12, no. 5: 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050654

APA StyleDimitrova, E., & Zaborskis, A. (2025). Family Support, Communication with Parents, and Adolescent Health Risk Behaviour: A Case of HBSC Study from Bulgaria and Lithuania. Children, 12(5), 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050654