Pediatric Tracheotomy: Modern Surgical Techniques, Challenges, and Clinical Considerations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Specific Considerations for Performing Tracheotomy in Pediatric Patients

- The size of the hyoid bone in children often exceeds that of the thyroid cartilage, making the palpation of anatomical landmarks more challenging.

- The thyrohyoid membrane is significantly shorter in infants.

- The cricoid cartilage is the narrowest part of the airway in children, whereas the glottic opening is the narrowest in adults.

- The pediatric trachea is shorter, narrower, and more compliant, increases the risk of tracheomalacia and airway collapse.

- In infants and young children, the larynx is located higher in the neck (around C3–C4 compared to C5–C6 in adults), making access to the trachea more challenging.

- The pediatric thyroid gland is proportionally larger and highly vascularized, increasing the risk of bleeding during surgery.

- The supraglottis and subglottis mucosa are more relaxed in infants, making them more susceptible to swelling in the case of inflammation or injury.

3. Surgical Techniques for Performing Tracheotomy in Childhood

- According to statistical data, between 40% and 50% of pediatric tracheostomies are performed in infants under one year age. They have extremely small airways, making the palpation of the anatomical landmarks very difficult. This, in turn, significantly complicates the accurate insertion of the needle, guidewire, dilators, and tracheostomy cannula through the soft tissues into the correct anatomical section of the neck.

- The trachea in children is much more mobile and softer than the adult trachea. As a result, there is an increased risk of tracheal collapse when pressure is applied with the dilators, which in turn raises the risk of posterior tracheal wall damage.

- In some cases, the underlying condition or disease requiring tracheostomy can also be a limiting factor. For example, in cases of subglottic stenosis, tracheal stenosis, or tracheomalacia, performing percutaneous tracheostomy in a narrowed tracheal lumen can be extremely challenging.

- Accidental decannulation in the early postoperative period can be fatal due to the smaller tracheostomy opening and the absence of stay sutures, which are typically placed during a classical pediatric tracheotomy. These sutures help facilitate both the replacement of the tracheostomy cannula in the first few days after surgery and recannulation in the case of accidental decannulation.

4. Classical Tracheotomy

- The child is placed in the supine position with the head in maximum deflection.

- Careful palpation of the anatomical landmarks is performed to identify the cricoid cartilage and jugular notch [3].

- Stepwise infiltration of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and underlying soft structures was performed with a solution of local anesthetic and adrenaline to reduce intraoperative bleeding. If a tracheotomy is performed under local anesthesia (which is rare in pediatric patients), infiltration is usually multi-stage.

- A midline incision is made on the neck, halfway between the cricoid cartilage and the jugular notch (Figure 1). The incision can be either horizontal or vertical, with a horizontal incision being used in most cases.

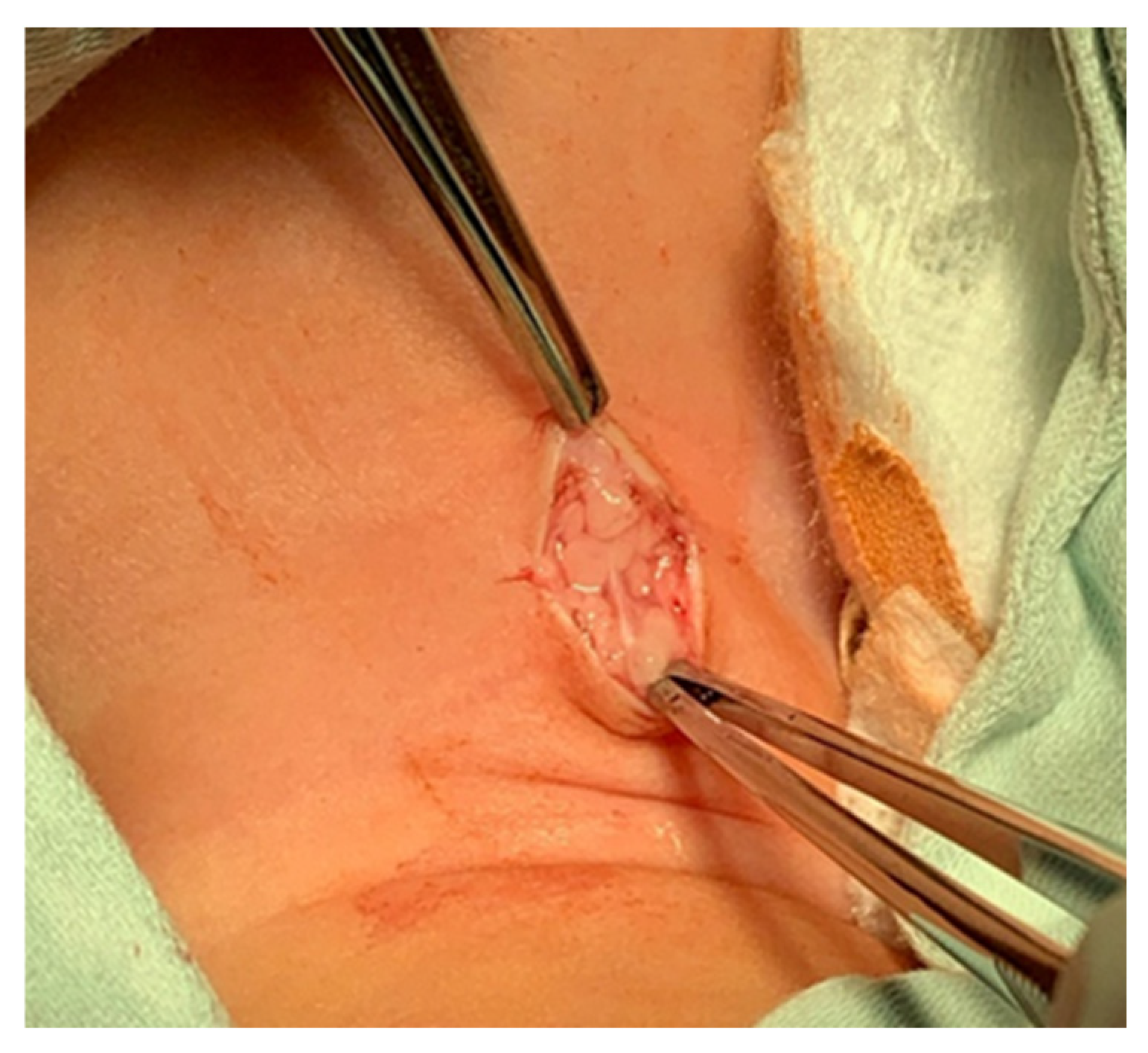

- The subcutaneous tissue is carefully dissected (Figure 2).

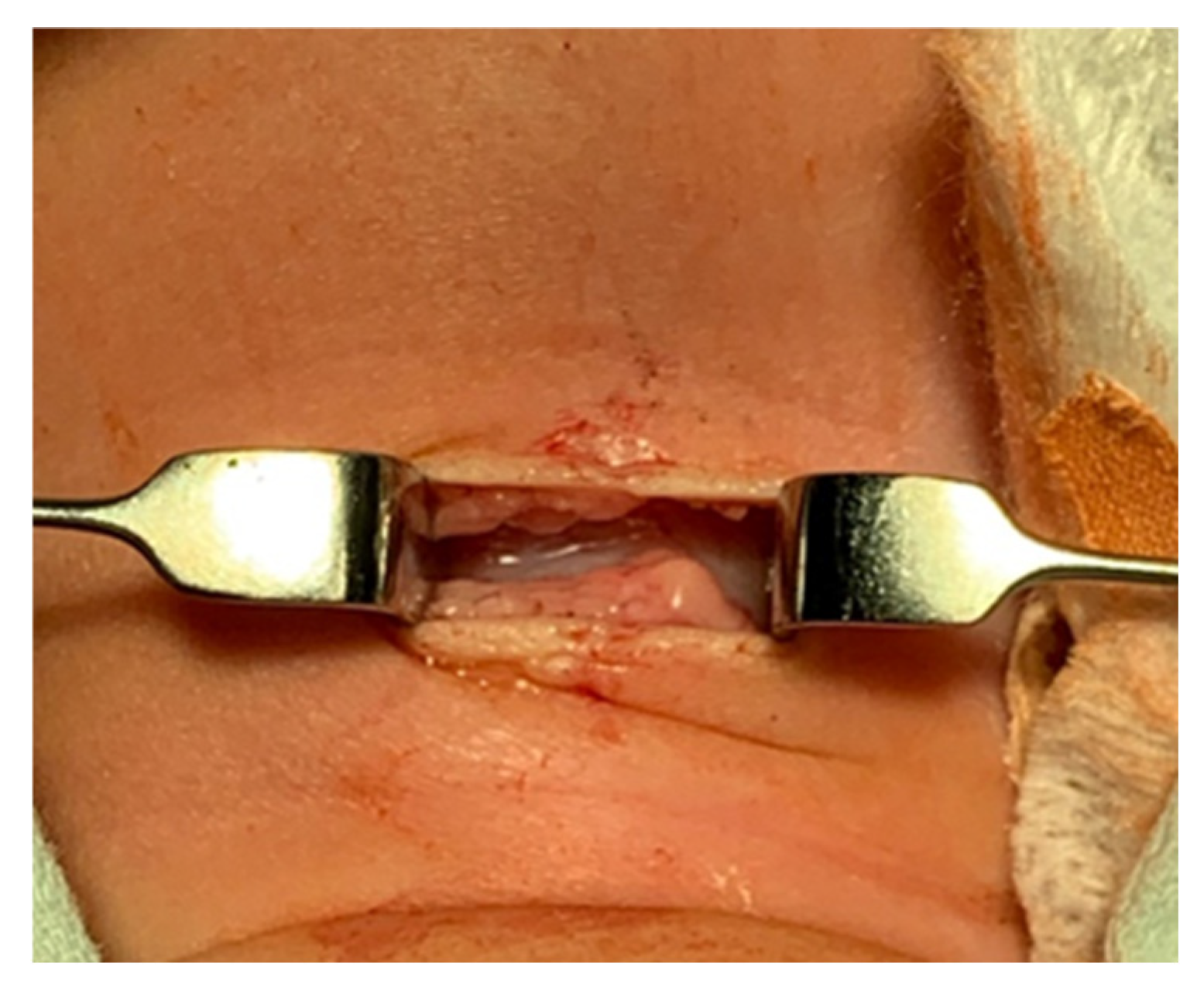

- The platysma is reached, and its muscles are separated and retracted using retractors (Figure 3).

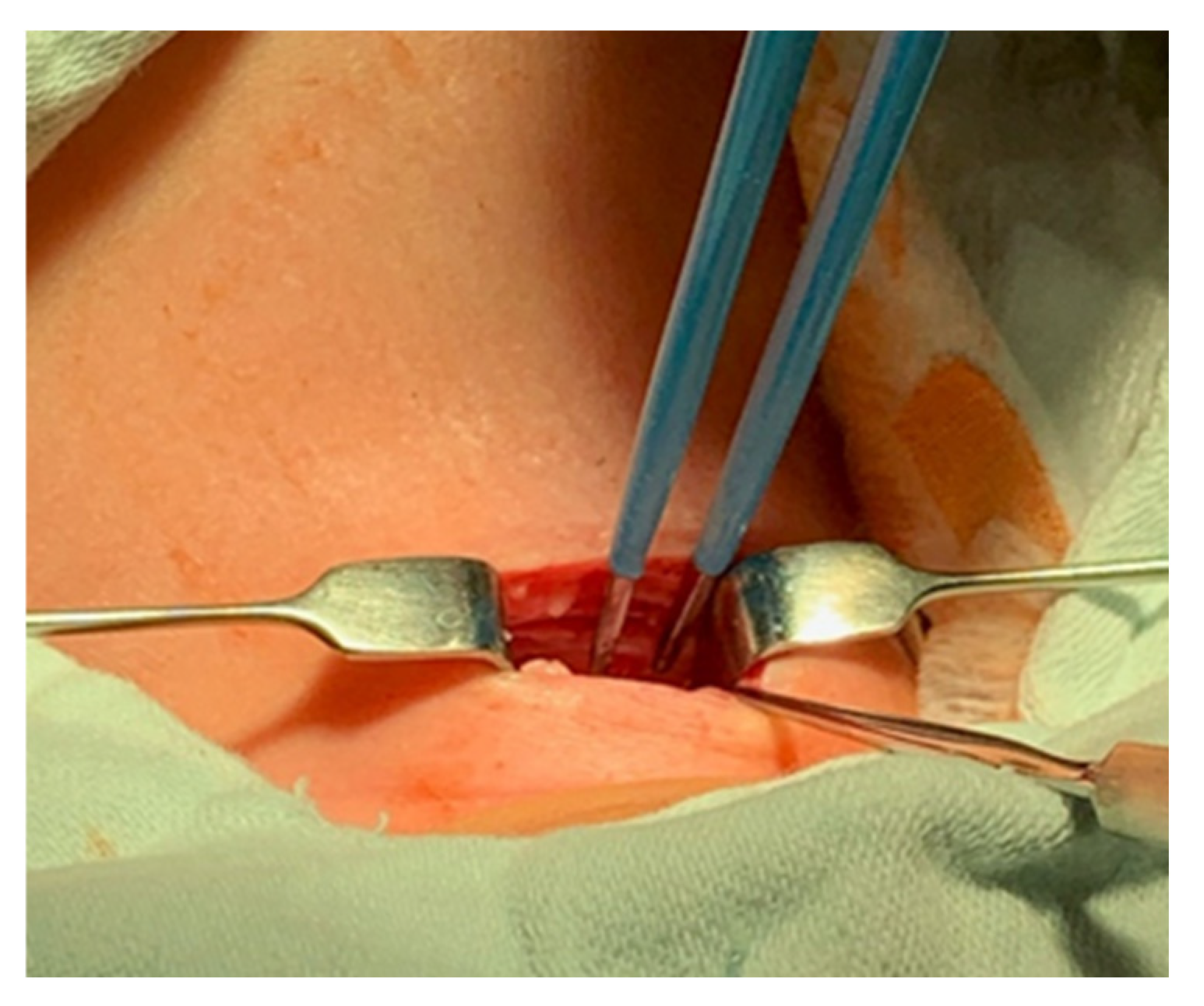

- Bipolar cautery is used during the procedure for hemostasis (Figure 4).

- The pretracheal longitudinal muscles are exposed, separated along the midline of the neck, and retracted laterally.

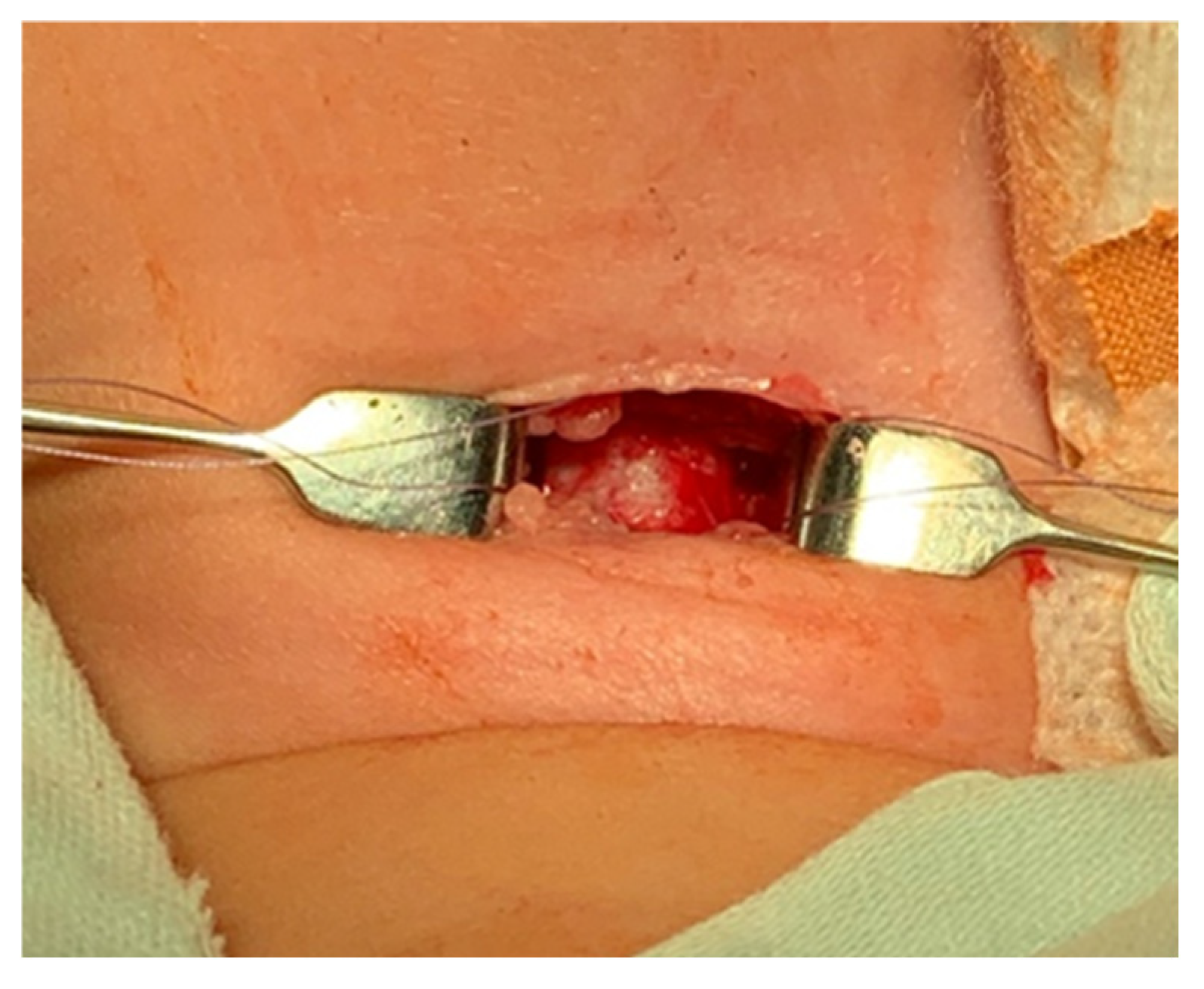

- If the thyroid isthmus covers the trachea and it is impossible to displace it cranially or caudally, it is clamped and cut. Since the thyroid gland is a well-vascularized parenchymal organ, cauterization is used for hemostasis, and the edges of the incision are almost always additionally sutured [3].

- The anterior surface of the trachea is exposed along 3–4 rings.

- The larynx and trachea are pulled upward and secured using a hook.

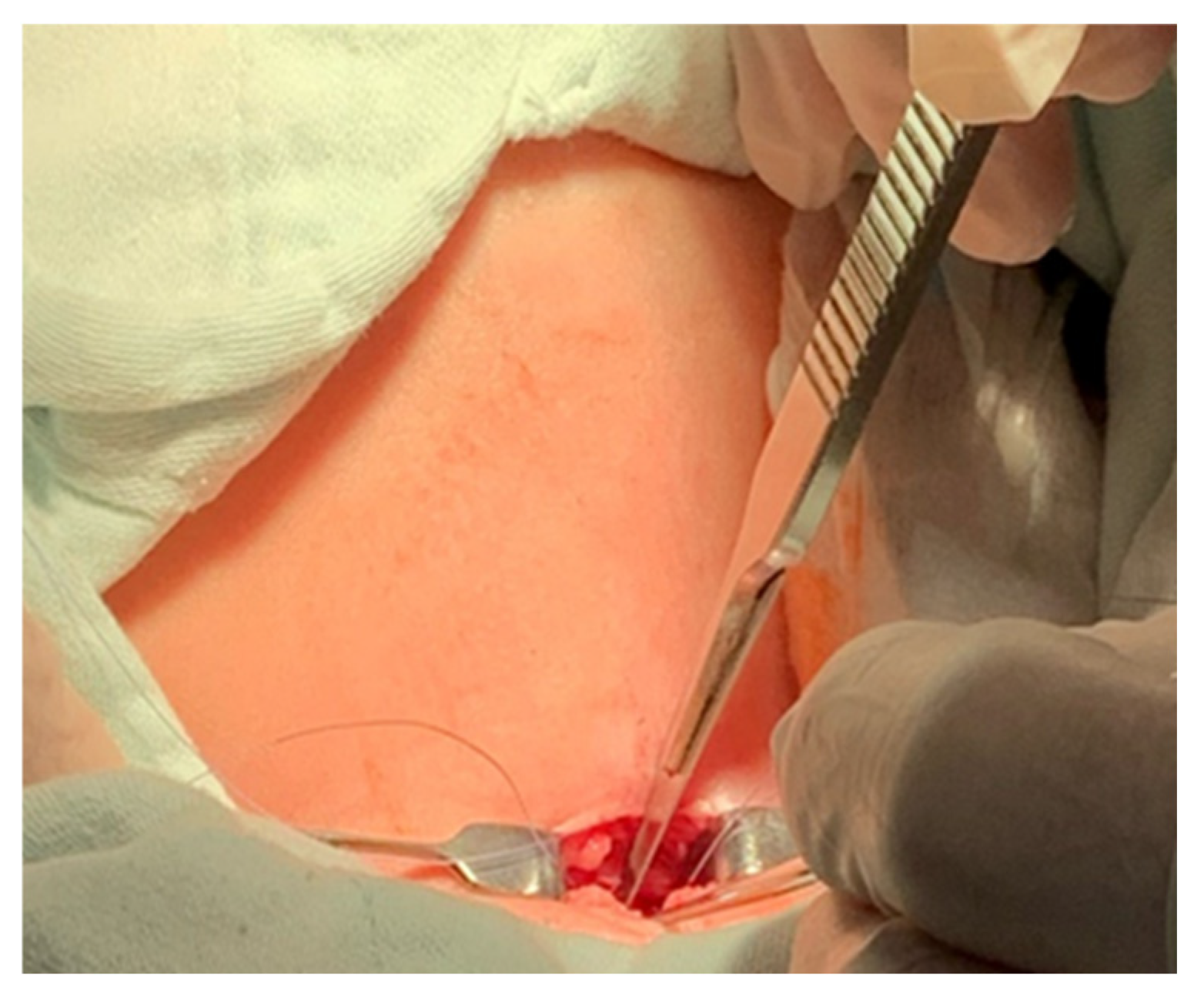

- Some authors recommend the routine placement of two sutures vertically on either side of the future tracheal incision (stay sutures) to facilitate easier and faster recannulation in case of accidental decannulation, as well as during the cannula change in the first few days after surgery (Figure 5) [3].

- A vertical or horizontal incision is made on the trachea, usually between the 2nd and 4th tracheal rings (Figure 6).

- A tracheal dilator is used to expand the tracheal incision.

- The endotracheal tube is identified, and after deflating the cuff, it is gradually pulled upward until positioned just below the vocal cords.

- With the help of the guidewire, the cannula is inserted into the lumen of the trachea, after which the guidewire is removed.

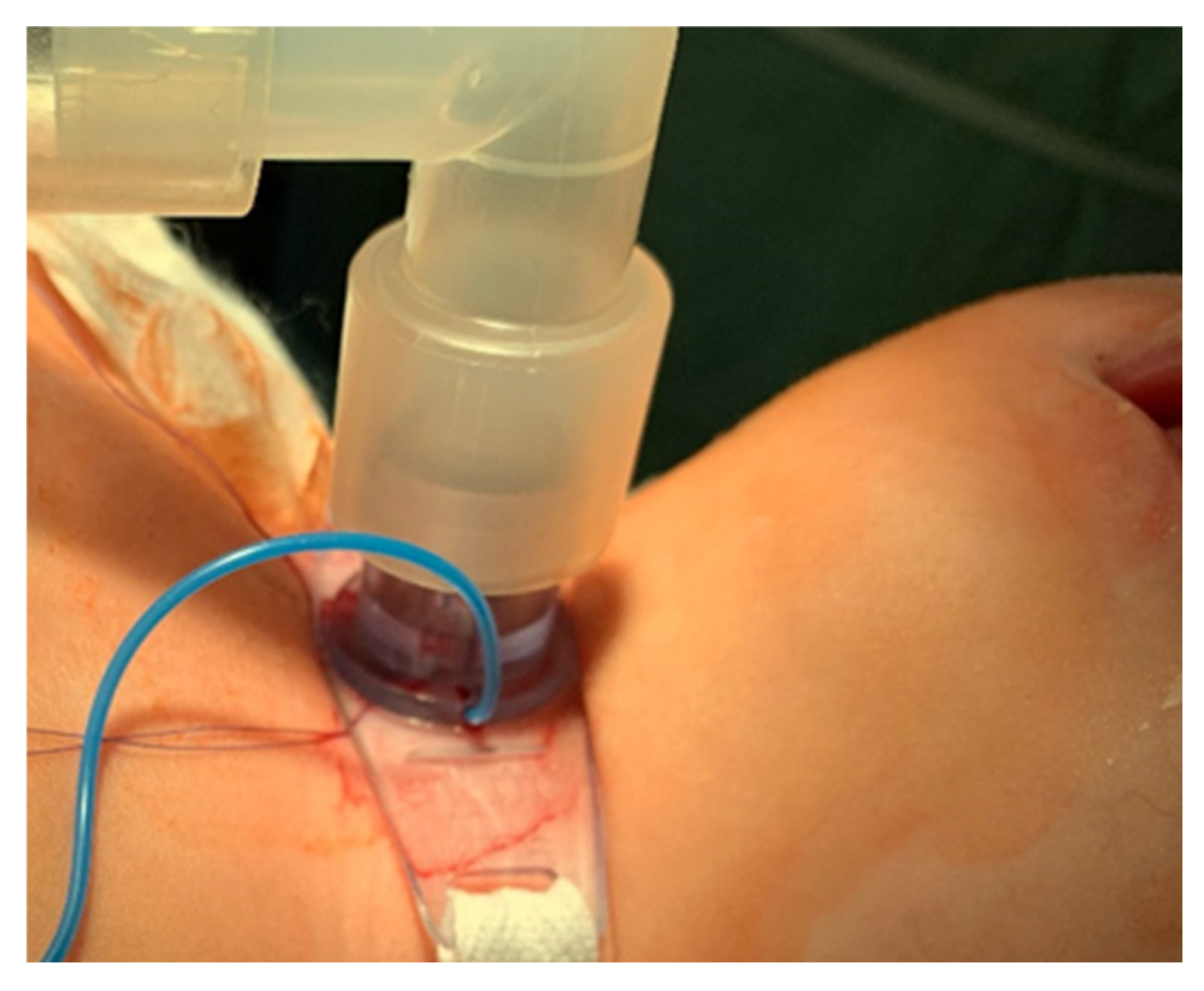

- The cannula is connected to the ventilator, and its cuff is inflated (Figure 7).

- After confirming the correct position of the cannula, the hook and retractor are removed.

- The cannula is secured around the patient’s neck with ties, and, in rare cases, it may also be sutured to the skin.

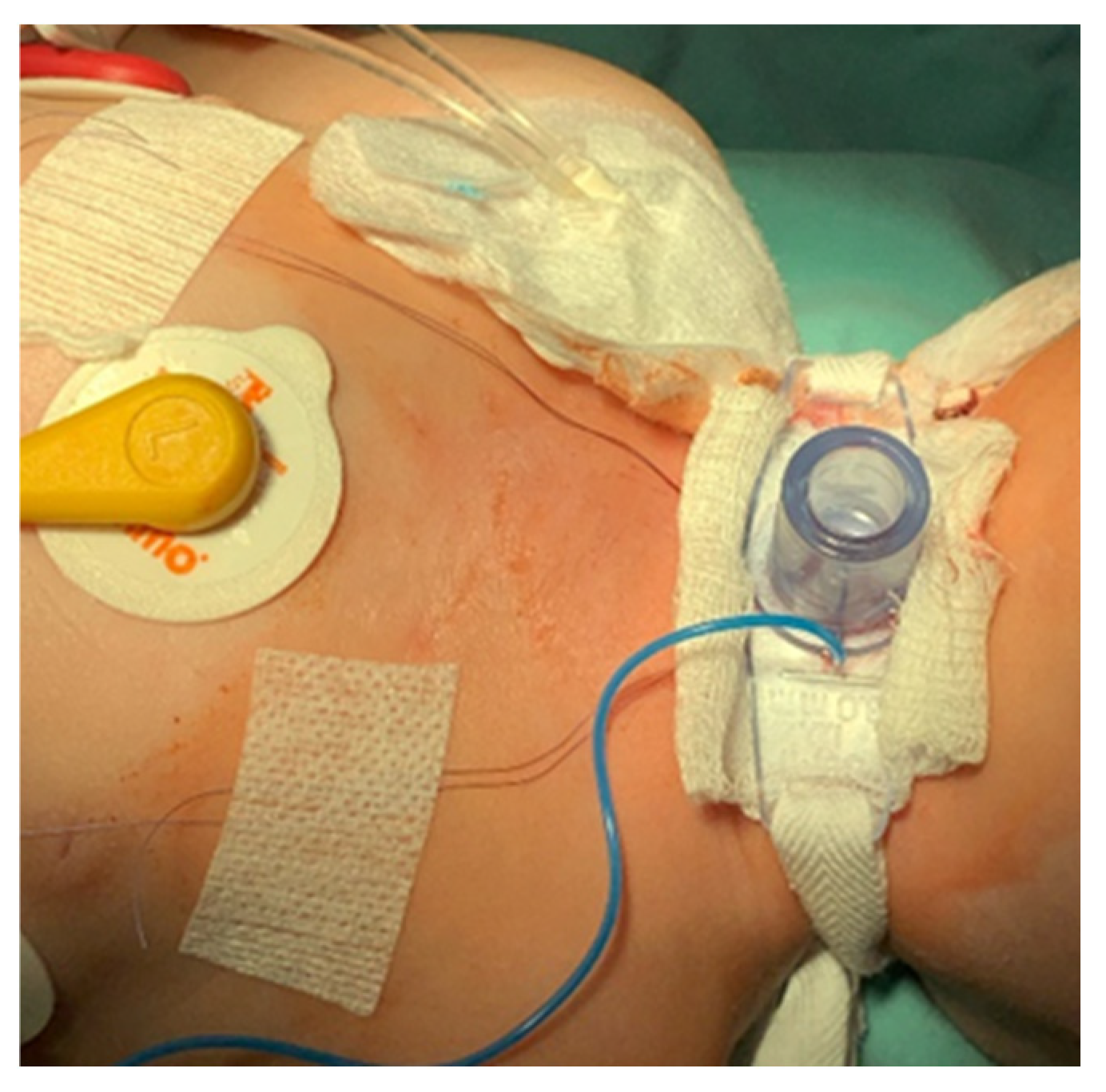

- If stay sutures have been placed on the trachea, they are secured to the patient’s chest and are clearly labeled as “left” and “right.” (Figure 8). These sutures are typically removed during the first or second cannula changes.

- A soft padding is placed under the cannula plate to prevent irritation or injury.

5. Permanent Tracheostoma Formation

- A cruciate or X-shaped neck skin incision is made midway between the cricoid cartilage and the jugular notch of the sternum (Figure 11). In children under one year of age, each skin incision forming the X should be 1 cm long. In older children, the incision length is proportionally increased, reaching up to 2 cm in adolescents.

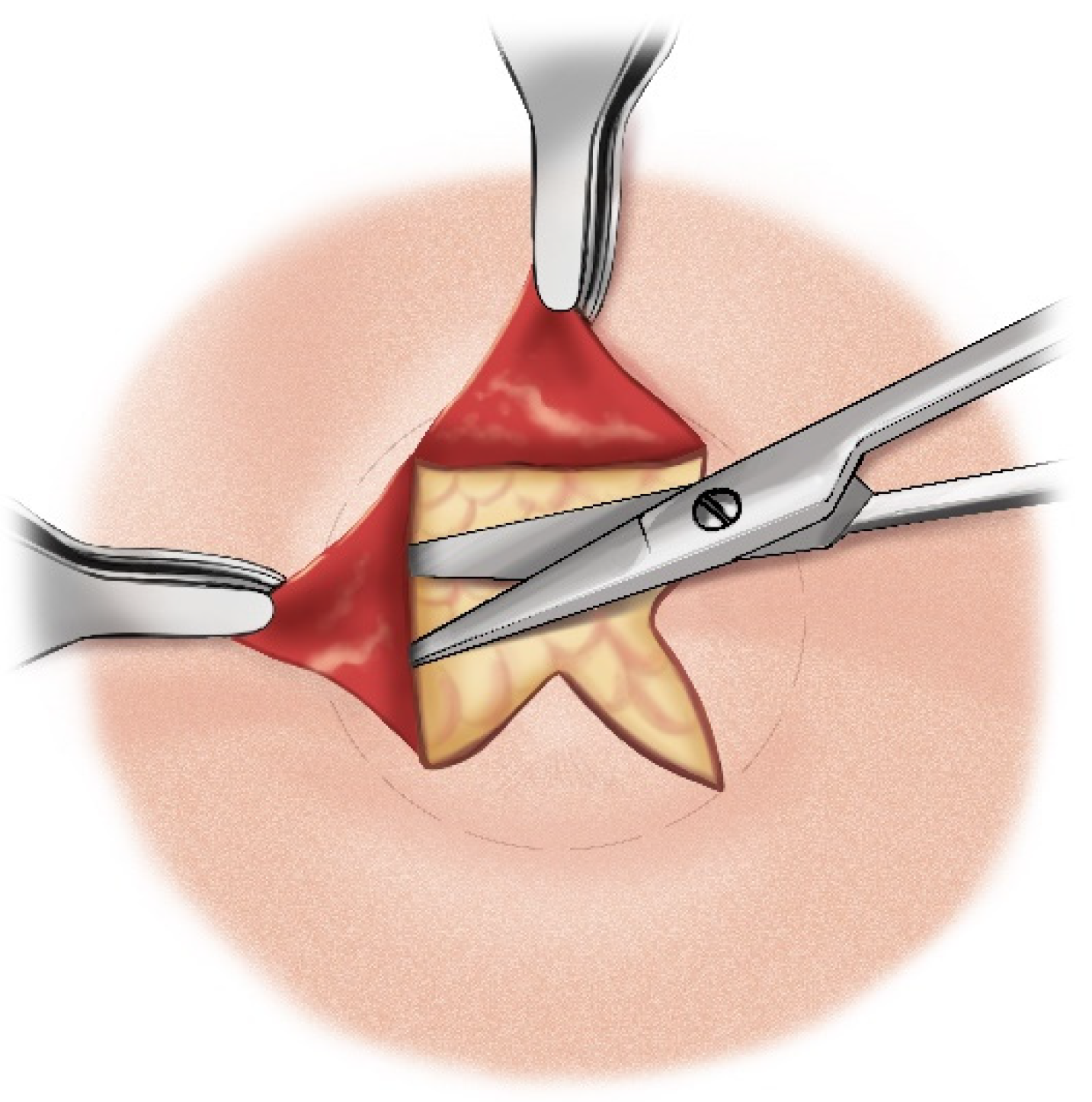

- The resulting triangular skin flaps are dissected from the underlying tissues using a dissecting scissors (Figure 12).

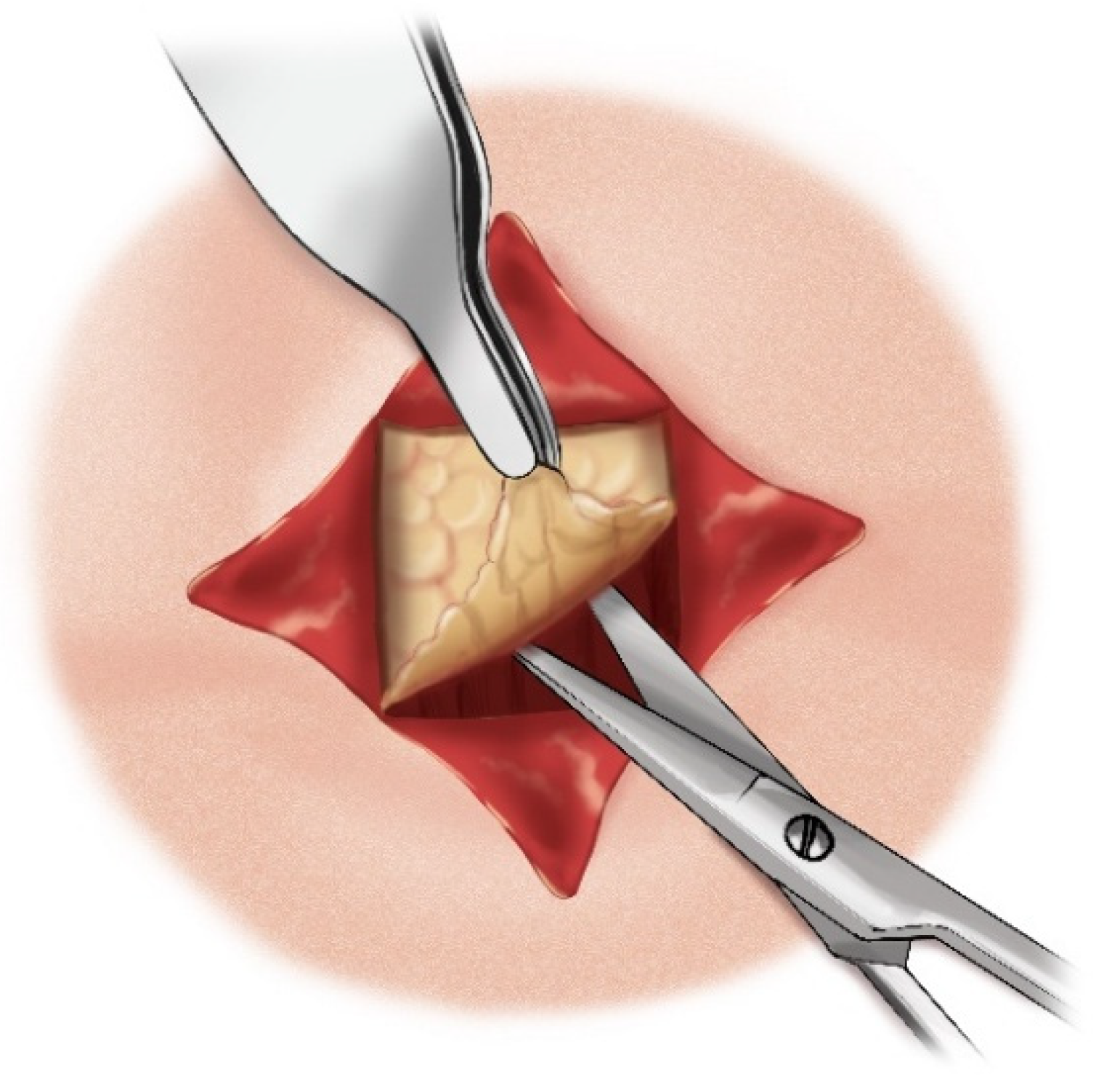

- The subcutaneous adipose tissue covering the elongated neck muscles is removed (Figure 13).

- The pretracheal connective tissues (pretracheal fascia) are dissected to expose the trachea.

- Typically, the isthmus of the thyroid gland remains above the dissection field; however, in cases where it covers the trachea, it may be longitudinally divided, and the lobes of the gland sutured.

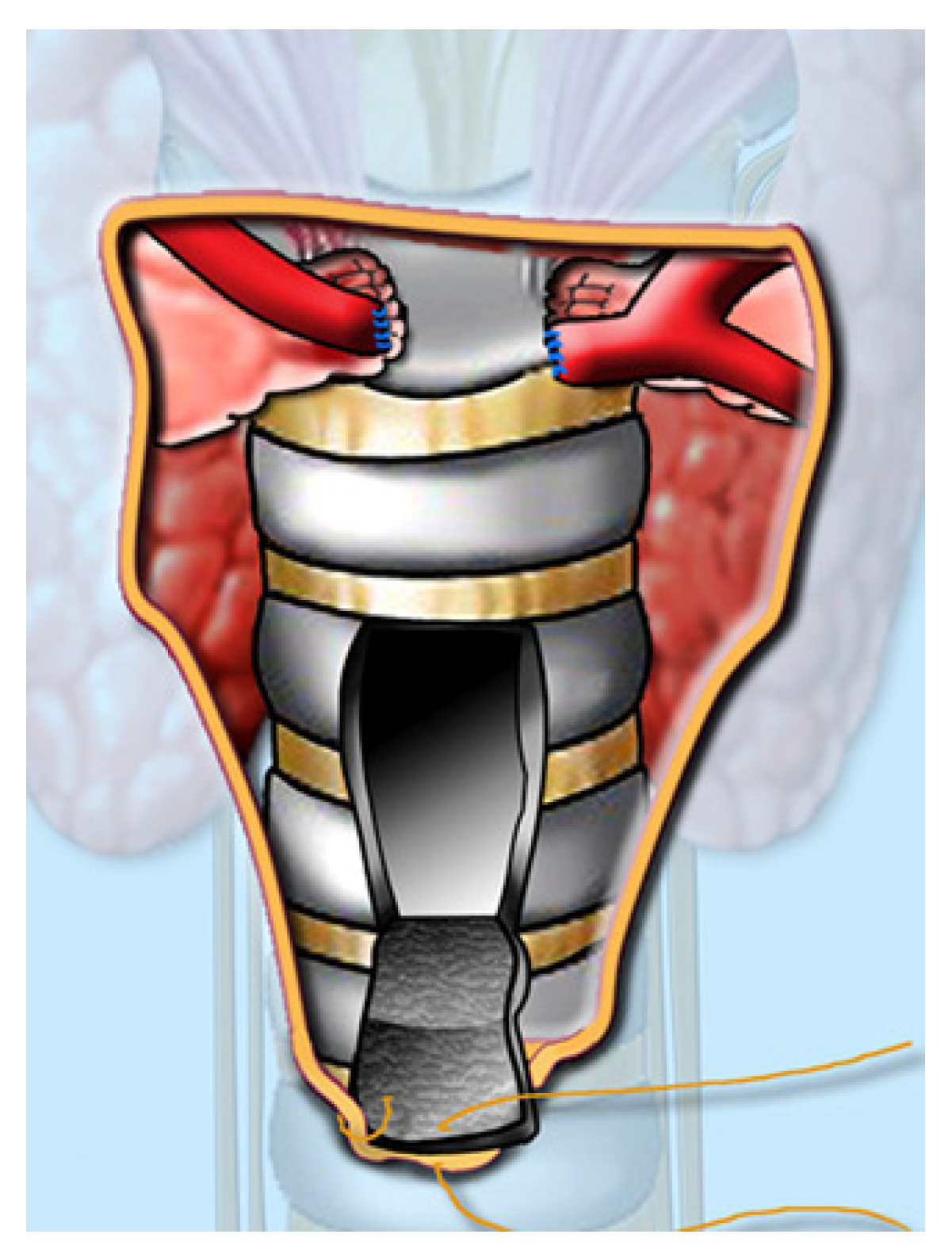

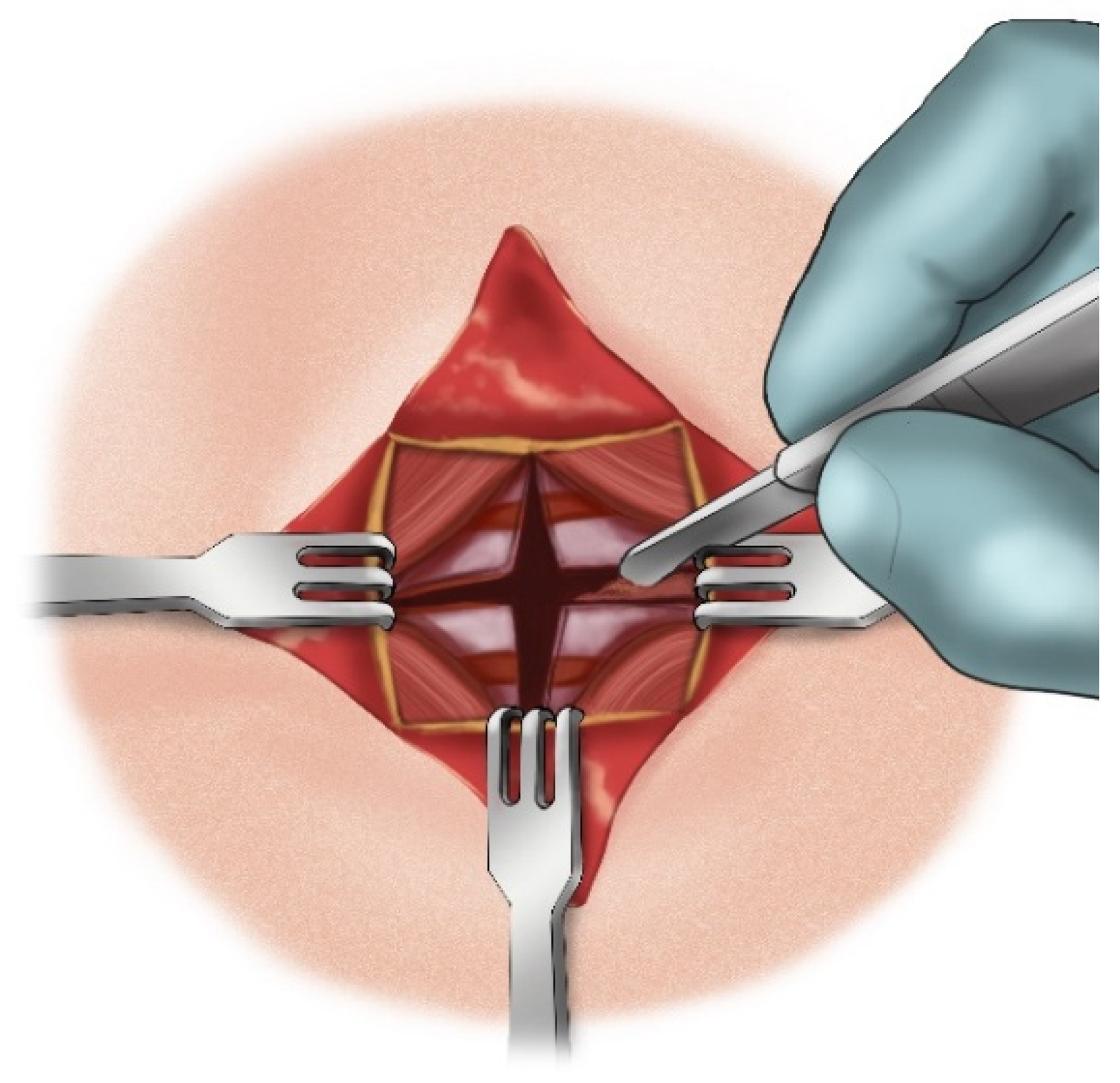

- A vertical incision is made on the anterior tracheal wall, encompassing four tracheal rings, followed by a horizontal incision in the middle of the vertical incision (two tracheal rings above and two tracheal rings below), thus creating a shape resembling a plus sign (+) (Figure 14).

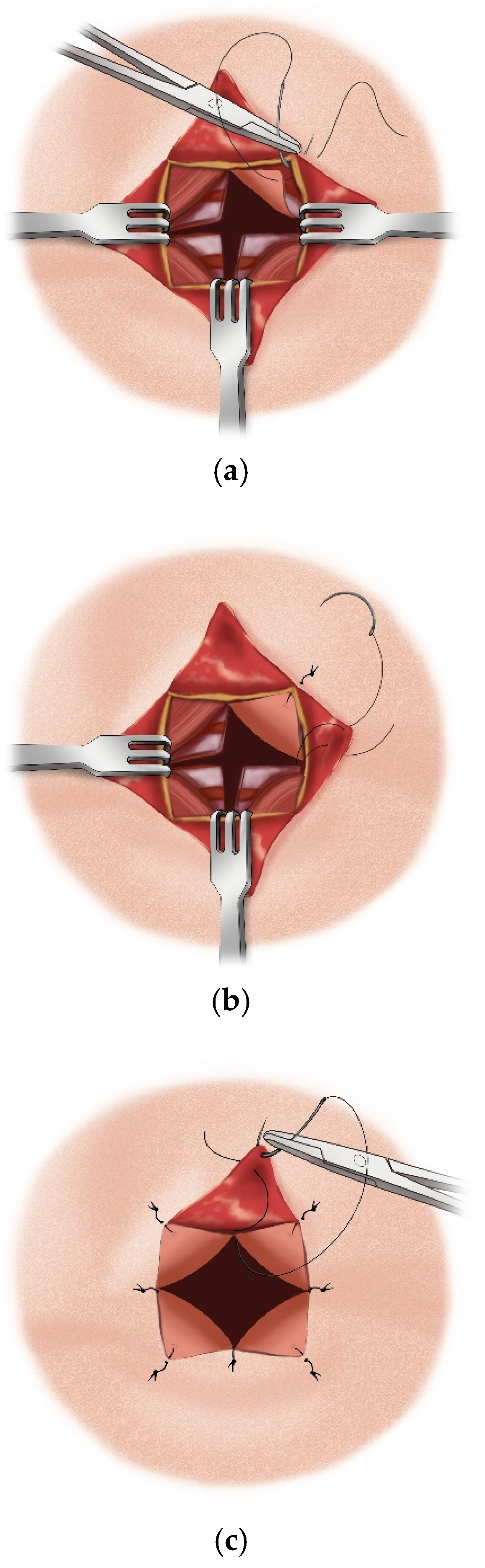

- The triangular skin flaps and tracheal flaps are integrated at the periphery, using Vicryl 5.0 sutures. First, the tip of the right upper tracheal flap is sutured to the base of the right upper skin flap (Figure 15a), and then the base of the adjacent tracheal flap is sutured to the tip of the adjacent skin flap (Figure 15b). The remaining flaps are sutured sequentially in the same manner until the tracheostomy is formed. Since the skin and tracheal incisions diverge at an angle of 45°, the tips of the tracheal flaps fit into the indentations of the skin flaps, and the tips of the skin flaps tightly conform to the indentations of the tracheal flaps (Figure 15c).

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watters, K.F. Tracheostomy in Infants and Children. Respir. Care 2017, 62, 799–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.Y.; Chiu, N.C.; Lee, K.S.; Chi, H.; Huang, F.Y.; Huang, D.T.N.; Chang, L.; Kung, Y.H.; Huang, C.Y. Respiratory tract infections in children with tracheostomy. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, P.; Forte, V. Pediatric tracheostomy. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2016, 25, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, A.; Cocuzza, S.; Longo, M.R.; Grillo, C.; Bonfiglio, M.; Pavone, P. Tracheostomy in childhood new cases for an old strategy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 16, 1719–1722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, A.E. Tracheostomy in children: Recommendations for a safer technique. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 30, 151054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, J.M.; Davis, S.; Albamonte-Petrick, S.; Chatburn, R.L.; Fitton, C.; Green, C.; Johnston, J.; Lyrene, R.K.; Myer, C., 3rd; Othersen, H.B.; et al. Care of the child with a chronic tracheostomy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 161, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neto, J.F.L.; Castagno, O.C.; Schuster, A.K. Complications of tracheostomy in children: A systematic review. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 88, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veder, L.L.; Joosten, K.F.M.; Zondag, M.D.; Pullens, B. Indications and clinical outcome in pediatric tracheostomy: Lessons learned. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 151, 110927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koltai, P.J. Starplasty A new technique of pediatric tracheotomy. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1998, 124, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, A.C.; Rogers, J.H. The changing indications for tracheostomy in children. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1987, 101, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcand, P.; Granger, J. Pediatric tracheostomies: Changing trends. J. Otolaryngol. 1988, 17, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.C.; Soares, J.J.; Elder, L.; Hill, L.; Abts, M.; Bonilla-Velez, J.; Dahl, J.P.; Johnson, K.E.; Ong, T.; Striegl, A.M.; et al. Surveillance en- doscopy after tracheostomy placement in children: Findings and interventions. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, S. Practice patterns after tracheotomy in infants younger than 2 years. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 137, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itamoto, C.H.; Lima, B.T.; Sato, J.; Fujita, R.R. Indications and Complications of Tracheostomy in Children. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2010, 76, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Classical Tracheotomy | Koltai Tracheotomy |

|---|---|---|

| Target Population | Adults and children | Primarily, children (especially infants and young children) |

| Purpose | To secure the airway | To secure the airway with minimal trauma and improved stability |

| Surgical Approach | Open incision with horizontal cutting of tracheal rings | Vertical incision through 2–3 tracheal rings without excising cartilage |

| Cannula Fixation | Usually with neck ties | Cannula is stabilized by the shape of the incision—no sutures needed |

| Complications (General) | Higher risk of granulation, stenosis, and displacement | Lower risk of stenosis and improved cannula stability |

| Postoperative Care | More challenging for small children | Easier—reduced risk of accidental decannulation |

| Healing after Decannulation | Slower, often leaves a persistent fistula | Faster closure, often without the need for surgical revision |

| Characteristic | Surgical Tracheotomy (Classical) | Percutaneous Tracheotomy |

|---|---|---|

| Technique | Open surgical procedure with skin and tissue incision | Minimally invasive technique with puncture and dilation |

| Setting | Usually performed in the operating room | Typically performed in the intensive care unit |

| Procedure Duration | Longer (30–60 min) | Shorter (10–20 min) |

| Anesthesia | General or local | Usually local anesthesia with sedation |

| Risk of Complications | Higher—bleeding, infection, damage to adjacent structures | Lower—when performed correctly and on selected patients |

| Suitable for | Patients with anatomical anomalies, neck infections, tumors | Stable patients without contraindications |

| Scar Visibility | More noticeable | Less noticeable |

| Complication | Classical Tracheotomy | Björg Flap Tracheotomy | Koltai Tracheotomy | Percutaneous Tracheotomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tracheal Stenosis | Common—especially with horizontal incision of rings | Rare—flap provides better anatomical stability | Rare—vertical incision minimizes trauma to the trachea | Rare—minimally invasive technique with minimal trauma to the trachea |

| Granulation Around the Cannula | Common in prolonged cannulation | Less frequent—flap stability reduces the chance of granulation | Less frequent—less traumatic technique and stable cannula | Less frequent—smaller wound, fewer chances for infection or granulation |

| Cannula Displacement | More common—especially in children or restless patients | Rare—flap reduces the risk of displacement | Very rare—cannula is securely held by the incision shape | More common—can occur with improper placement or care |

| Intraoperative Bleeding | Possible—especially if thyroid or vessels are cut | Minimal—flap minimizes bleeding by avoiding major vessels | Minimal—minimally invasive technique avoids blood vessels | Very rare—minimally invasive approach with low bleeding risk |

| Wound Site Infection | Possible with improper care | Less common—minimal incision and flap stability | Less common—smaller incision and better healing of the wound | Similar risk, but smaller wound and less external exposure |

| Persistent Tracheocutaneous Fistula | Common after decannulation with prolonged cannulation duration | Less frequent—flap stability aids faster healing | Less frequent—faster closure after decannulation | Less frequent—minimal incision and faster healing |

| Patient Age | Inner Diameter (mm) |

|---|---|

| Premature (less than 1000 g) | 2.5 |

| 1000–2500 g | 3.0 |

| Newborn to 6 months | 3.0–3.5 |

| 6 months to 1 year | 3.5–4.0 |

| 1–2 years | 4.0–5.0 |

| Over 2 years | (Age in years +16)/4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markov, S.S.; Markova, P.P.; Madzarova-Nikolova, K.I. Pediatric Tracheotomy: Modern Surgical Techniques, Challenges, and Clinical Considerations. Children 2025, 12, 637. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050637

Markov SS, Markova PP, Madzarova-Nikolova KI. Pediatric Tracheotomy: Modern Surgical Techniques, Challenges, and Clinical Considerations. Children. 2025; 12(5):637. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050637

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkov, Stoyan S., Petya P. Markova, and Kalina I. Madzarova-Nikolova. 2025. "Pediatric Tracheotomy: Modern Surgical Techniques, Challenges, and Clinical Considerations" Children 12, no. 5: 637. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050637

APA StyleMarkov, S. S., Markova, P. P., & Madzarova-Nikolova, K. I. (2025). Pediatric Tracheotomy: Modern Surgical Techniques, Challenges, and Clinical Considerations. Children, 12(5), 637. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050637