Intervention Effects of Group Sandplay Therapy on Children at Risk of Smartphone Addiction: Focusing on Internalizing and Externalizing Problems in the Korean Youth Self Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

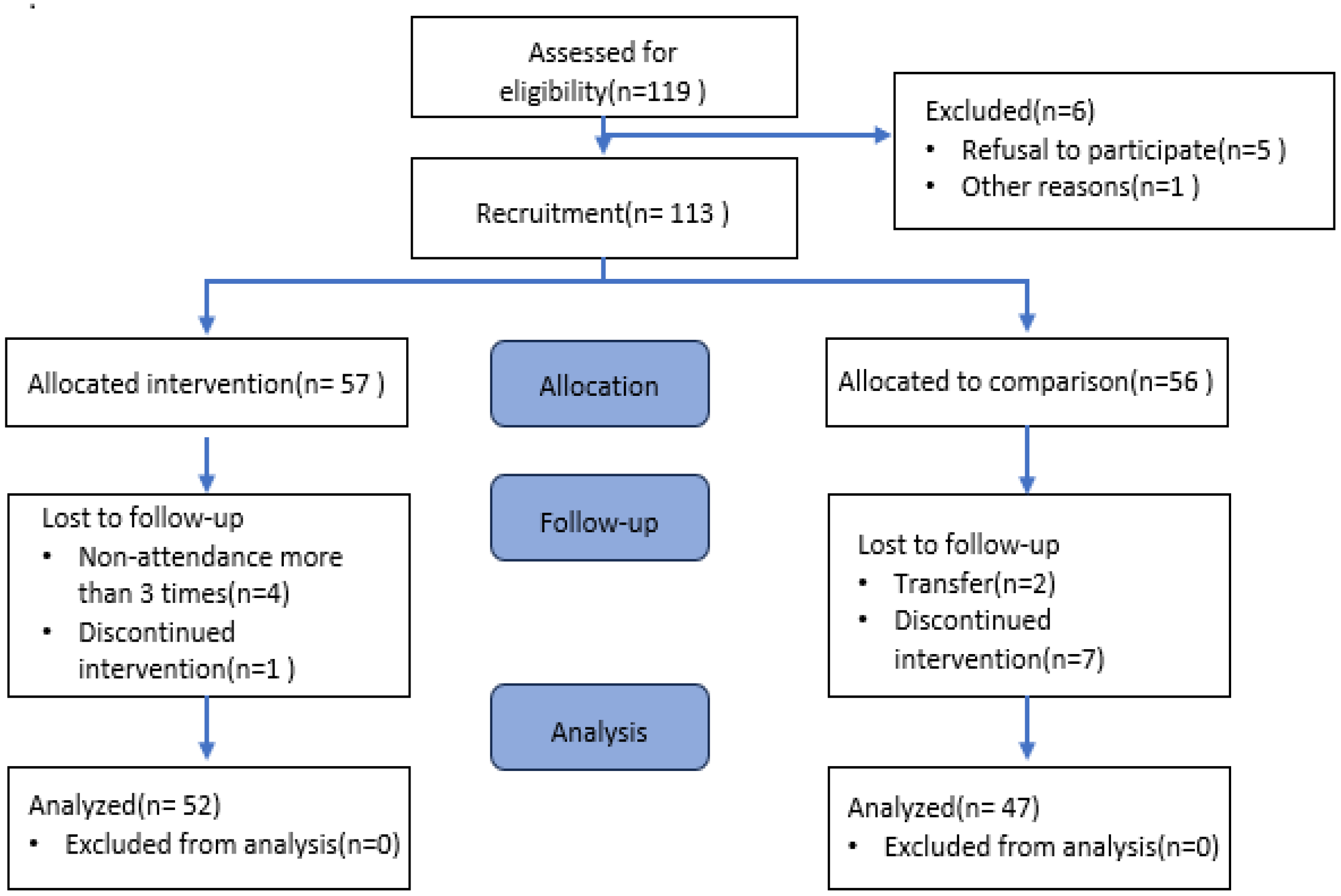

2.2. Participants

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Youth Smartphone Addiction Scale (S-Scale)

2.4.2. Korean Youth Self Report: K-YSR

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Changes in K-YSR After GST Intervention

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Science and ICT. 2023 Survey on the Internet Usage; Ministry of Science and ICT: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2023. Available online: https://www.msit.go.kr (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Demirci, K.; Orhan, H.; Demirdas, A.; Akpinar, A.; Sert, H. Validity and Reliability of the Turkish Version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale in a Younger Population. Bull. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyanova, A.; Gorbaniuk, O.; Blachnio, A.; Przepiórka, A.; Mraka, N.; Polishchuk, V.; Gorbaniuk, J. Mobile Phone Addiction, Phubbing, and Depression Among Men and Women: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Karila, L.; Billieux, J. Internet Addiction: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Research for the Last Decade. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4026–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.Y.; Rees, P.; Wildridge, B.; Kalk, N.J.; Carter, B. Prevalence of Problematic Smartphone Usage and Associated Mental Health Outcomes Amongst Children and Young People: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and GRADE of the Evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Wacks, Y.; Weinstein, A.M. Excessive Smartphone Use Is Associated with Health Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 669042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.L.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, F.F. Depression and Internet Addiction Among Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 326, 115311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yan, N.; Mackay, L.E.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. The Longitudinal Relationships Between Problematic Smartphone Use and Anxiety Symptoms Among Chinese College Students: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis. Addict. Behav. 2025, 160, 108170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Yee, J.; Chung, J.E.; Kim, H.J.; Han, J.M.; Kim, J.H.; Gwak, H.S. Smartphone Addiction and Anxiety in Adolescents—A Cross-Sectional Study. Am. J. Health Behav. 2021, 45, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jin, C.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ren, Y. The Mediating Role of Inhibitory Control and the Moderating Role of Family Support Between Anxiety and Internet Addiction in Chinese Adolescents. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2024, 53, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Malaeb, D.; Sarray El Dine, A.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. The Relationship Between Smartphone Addiction and Aggression Among Lebanese Adolescents. World J. Sand Ther. Pract. 2022, 2, 735. [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni, L.; Portoghese, I.; Congiu, A.; Carli, S.; Munari, R.; Federico, A.; Lugoboni, F. Internet Addiction and Related Clinical Problems: A Study on Italian Young Adults. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 571638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.G.; Park, J.; Kim, H.T.; Pan, Z.; Lee, Y.; McIntyre, R.S. The Relationship Between Smartphone Addiction and Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity in South Korean Adolescents. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2019, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.Q.; Yao, N.Q.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Lv, Z.T. The Association Between Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Internet Addiction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; O’Brien, K.D.; Armour, C. Distress Tolerance and Mindfulness Mediate Relations Between Depression and Anxiety Sensitivity with Problematic Smartphone Use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, B.M.; Park, E.; Kwon, J.G.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, D. Associations of Personality and Clinical Characteristics with Excessive Internet and Smartphone Use in Adolescents: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Addict. Behav. 2020, 110, 106485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Kim, T.H. The Effect of Group Art Therapy on the Delay of Gratification of Children with Smartphone Addiction. Forum Youth Cult. 2019, 58, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, M.L.; Padrón, I.; Fumero, A.; Marrero, R.J. Effects of Internet and Smartphone Addiction on Cognitive Control in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review of fMRI Studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 159, 105572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, K.Y.; Kim, C.B. Predicting Smartphone Addiction Trajectories in Korean Adolescents: A Longitudinal Analysis of Protective and Risk Factors Based on a National Survey from 2018 to 2020. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health 2024, 36, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, S.J. Prevalence and Predictors of Smartphone Addiction Proneness Among Korean Adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 77, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Ran, H.; Yuan, J.; Zhao, L. The Experiences in Close Relationship and Internet Addiction Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model of Anxiety and Information Cocoon. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 366, 117641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Zhou, B. Internet Addiction and Depression Among Chinese Adolescents: Anxiety as a Mediator and Social Support as a Moderator. Psychol. Health Med. 2023, 28, 2315–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.S.; Liu, T.H.; Qin, D.; Wang, Z.P.; He, X.Y.; Chen, Y.N. Effects of Non-Pharmacological Interventions on Youth with Internet Addiction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1327200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinauskas, R.; Malinauskiene, V. A Meta-Analysis of Psychological Interventions for Internet/Smartphone Addiction Among Adolescents. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Yin, H.; Meng, T.; Guo, X. Effects of Sandplay Therapy in Reducing Emotional and Behavioural Problems in School-Age Children with Chronic Diseases: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 3099–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesler, C. Sandplay Therapy: An Overview of Theory, Applications and Evidence Base. Arts Psychother. 2019, 64, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boik, B.; Goodwin, E.A. Sandplay Therapy: A Step-by-Step Manual for Psychotherapists of Diverse Orientations; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.L.R.; Ouyang, G. Impact of Child-Centered Play Therapy Intervention on Children with Autism Reflected by Brain EEG Activity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2024, 112, 102336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Kim, Y.J. The Effects of Group Sandplay Therapy on Peer Attachment, Impulsiveness, and Social Anxiety of Adolescents Addicted to Smartphones. J. Symb. Sandplay Ther. 2015, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestly, T.A. The Interpersonal Neurobiology of Play: Brain-Building Interventions for Emotional Well-Being; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kalff, D.M. Introduction to Sandplay Therapy. J. Sandplay Ther. 1991, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.J.; Ahn, U.K.; Lim, M.H. The Clinical Effects of School Sandplay Group Therapy on General Children with a Focus on Korea Child & Youth Personality Test. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Information Society Agency (NIA). 2011 Survey on Internet Addiction; National Information Society Agency (NIA): Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. Available online: https://www.nia.or.kr (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Achenbach, T.M. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile; University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, K.J.; Ha, E.H.; Lee, H.L.; Hong, K.E. Korean Youth Self Report; JungAng Aptitude Publication: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.H.; Jang, M. Effect of Group Sandplay Therapy on Addicted Youth’s Addiction Levels and Anxiety. J. Symb. Sandplay Ther. 2015, 7, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihm, J. Social Implications of Children’s Smartphone Addiction: The Role of Support Networks and Social Engagement. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pera, A. The Psychology of Addictive Smartphone Behavior in Young Adults: Problematic Use, Social Anxiety, and Depressive Stress. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 573473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, M.; Freedle, L.R.; Sani, R.; Fonda, G. The Effect of Sandplay Therapy on the Thalamus in the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Case Report. Int. J. Play Ther. 2020, 29, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kwak, H.J.; Ahn, U.K.; Kim, K.M.; Lim, M.H. Effect of Group Sand Play Therapy on Psychopathologies of Adolescents with Delinquent Behaviors. Medicine 2023, 102, e35445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, C.; Benoit, M.; Lacroix, L.; Gauthier, M.F. Evaluation of a Sandplay Program for Preschoolers in a Multiethnic Neighborhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herce, N.B.; de Alda, I.O.; Marrodán, J.L.G. Sand Tray and Sandplay in the Treatment of Trauma with Children and Adolescents: A Systemic Review. World J. Sand Ther. Pract. 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubenzadeh, S.; Abedin, A. Effectiveness of Sand Tray Short-Term Group Therapy with Grieving Youth. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 69, 2131–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Jin, L.; Cui, C.; Cui, M. A Study on the Effects of Sandplay Therapy on Second-Grade Middle School Students with PTSD. J. Symb. Sandplay Ther. 2019, 10, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.R.; Jang, M.; Shim, J. The Effectiveness of Group Sandplay Therapy on Quality of Peer Relationships and Behavioral Problems of Korean-Chinese Children in China. J. Symb. Sandplay Ther. 2018, 9, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi Keivani, S.N.; Abolmaali, K. Effectiveness of Sand Tray Therapy on Emotional-Behavioral Problems in Preschool Children. Iran. J. Learn. Mem. 2018, 1, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, E.; Jang, M. Effects of Sandplay Therapy on Aggression and Brain Waves of Female Juvenile Delinquents. J. Symb. Sandplay Ther. 2013, 4, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.J.; Park, M.H. The Effect of Sandplay Group Counseling on Emotional and Behavioral Problems at a Local Children’s Center. Sch. Couns. Sandplay 2020, 2, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Gontard, A.; Löwen-Seifert, S.; Wachter, U.; Kumru, Z.; Becker-Wördenweber, E.; Hochadel, M.; Senges, C. Sandplay Therapy Study: A Prospective Outcome Study of Sandplay Therapy with Children and Adolescents. J. Sandplay Ther. 2010, 19, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, Q.; Yu, S. Child Neglect, Psychological Abuse and Smartphone Addiction Among Chinese Adolescents: The Roles of Emotional Intelligence and Coping Style. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homeyer, L.E.; Sweeney, D.S. Sandtray Therapy: A Practical Manual; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Directives | Session | Sandplay Therapy Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Departure | 1 | Feel the texture of the sand and express your thoughts and feelings. |

| Self-emotional contact | 2 | Close your eyes. Touch the sand and express the emotions that arise from its texture in the sand tray. |

| 3 | Express the emotions you feel when recalling past memories. | |

| Conflict and struggle | 4 | Express any negative emotions you’re experiencing right now. |

| 5 | Recall and express an image of a hero overcoming hardship and adversity. | |

| Family, friends, school | 6 | Express your feelings while thinking about your family. |

| 7 | Express your thoughts and feelings about friends and school. | |

| Self-understanding and acceptance | 8 | Express yourself in the sand tray. |

| 9 | Recall the sandwork you’ve created thus far and express your feelings. | |

| Integration | 10 | Imagine and express a new version of yourself. |

| Variables | Intervention (n = 52) | Control (n = 47) | t/χ² | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 11.46 ± 0.50 | 11.30 ± 0.46 | 8.83 | 0.09 |

| Sex | 0.658 | 0.42 | ||

| Male | 18 (34.6) | 20 (42.6) | ||

| Female | 34 (65.4) | 27 (57.4) |

| Variables | Group (N) | Mean ± SD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Group F (p) | Time F (p) | Group × Time F (p) | η2 Interaction | ||

| Smartphone Addiction | Intervention (52) | 36.98 ± 6.18 | 32.35 ± 6.38 | 16.425 *** (3.7 × 10−4) | 19.311 *** (3.3 × 10−5) | 7.355 * (0.020) | 0.071 |

| Control (47) | 29.30 ± 4.65 | 29.15 ± 6.72 | |||||

| Anxiety/Depression | Intervention (52) | 61.02 ± 10.08 | 55.92 ± 9.99 | 3.712 (0.158) | 10.685 ** (0.002) | 3.792 (0.069) | 0.038 |

| Control (47) | 55.98 ± 9.47 | 55.45 ± 8.77 | |||||

| Withdrawal/Depression | Intervention (52) | 61.35 ± 10.60 | 57.21 ± 9.86 | 5.540 * (0.032) | 5.506 * (0.021) | 3.863 (0.093) | 0.038 |

| Control (47) | 54.85 ± 8.28 | 55.36 ± 7.88 | |||||

| Somatic Symptoms | Intervention (52) | 56.73 ± 6.52 | 54.10 ± 7.23 | 3.89 (0.391) | 0.589 (0.445) | 4.542 * (0.040) | 0.045 |

| Control (47) | 54.28 ± 7.05 | 55.89 ± 7.77 | |||||

| Delinquent Behavior | Intervention (52) | 55.46 ± 7.20 | 54.90 ± 6.53 | 2.149 (0.278) | 0.080 (0.778) | 2.332 (0.453) | 0.023 |

| Control (47) | 53.43 ± 4.17 | 54.38 ± 5.46 | |||||

| Aggressive Behavior | Intervention (52) | 58.71 ± 8.40 | 54.98 ± 7.44 | 0.391 (0.535) | 6.638 ** (0.012) | 2.937 (0.264) | 0.029 |

| Control (47) | 55.74 ± 7.07 | 55.83 ± 7.79 | |||||

| Social Problems | Intervention (52) | 60.15 ± 8.36 | 58.19 ± 9.76 | 1.069 (0.333) | 1.771 (0.187) | 4.865 (0.314) | 0.048 |

| Control (47) | 55.62 ± 7.99 | 57.21 ± 8.90 | |||||

| Thought Problems | Intervention (52) | 60.54 ± 9.25 | 58.19 ± 9.76 | 4.359 ** (0.044) | 2.120 (0.149) | 0.849 (0.380) | 0.036 |

| Control (47) | 55.47 ± 7.35 | 55.28 ± 8.43 | |||||

| Attention Problems | Intervention (52) | 57.46 ± 9.57 | 53.77 ± 7.53 | 2.900 (0.134) | 3.485 (0.066) | 2.447 (0.232) | 0.025 |

| Control (47) | 52.64 ± 5.36 | 53.04 ± 6.47 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.H.; Shin, H.; Bae, E.; Lee, Y.; Lee, C.M.; Shim, S.H.; Kim, M.S.; Lim, M.H. Intervention Effects of Group Sandplay Therapy on Children at Risk of Smartphone Addiction: Focusing on Internalizing and Externalizing Problems in the Korean Youth Self Report. Children 2025, 12, 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050593

Lee YH, Shin H, Bae E, Lee Y, Lee CM, Shim SH, Kim MS, Lim MH. Intervention Effects of Group Sandplay Therapy on Children at Risk of Smartphone Addiction: Focusing on Internalizing and Externalizing Problems in the Korean Youth Self Report. Children. 2025; 12(5):593. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050593

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Yang Hee, Heajin Shin, Eunju Bae, Youngil Lee, Chang Min Lee, Se Hoon Shim, Min Sun Kim, and Myung Ho Lim. 2025. "Intervention Effects of Group Sandplay Therapy on Children at Risk of Smartphone Addiction: Focusing on Internalizing and Externalizing Problems in the Korean Youth Self Report" Children 12, no. 5: 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050593

APA StyleLee, Y. H., Shin, H., Bae, E., Lee, Y., Lee, C. M., Shim, S. H., Kim, M. S., & Lim, M. H. (2025). Intervention Effects of Group Sandplay Therapy on Children at Risk of Smartphone Addiction: Focusing on Internalizing and Externalizing Problems in the Korean Youth Self Report. Children, 12(5), 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050593