Cultural Approaches to Addressing Sleep Deprivation and Improving Sleep Health in Japan: Sleep Issues Among Children and Adolescents Rooted in Self-Sacrifice and Asceticism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sleep Education

3. Perception of Sleep in Japan

3.1. Sleep in Japan Before the Emergence of Yōjōkun

3.2. Yōjōkun

3.3. From Yōjōkun to the End of World War II

3.4. After World War II

3.5. Summary of Section 3

4. Strategies

Summary of Section 4

5. Methodology

6. Future Prospects

7. Conclusions

- The undervaluation of sleep in Japan is hypothesized to stem from the cultural aesthetics of self-sacrifice and asceticism, particularly as embodied in the Bushidō spirit.

- Overcoming this deeply rooted aesthetic requires a critical evaluation of Bushidō’s limitations in modern society, rather than its uncritical veneration. These insights must be critically examined and effectively transmitted to future generations.

- A pivotal factor in promoting adequate sleep is the individual’s direct experience of recovery from sleep deprivation—specifically, recognizing the resolution of associated difficulties and the benefits of improved sleep.

- For children and adolescents, a key educational task is the introduction of methods to calculate each individual’s OSD, which may help foster awareness of personal sleep needs.

- Further research and replication studies are needed; however, the proposed formula for estimating individual OSD uses only bedtime on school nights and non-school nights, wake-up times on schooldays and non-schooldays, sleepiness, gender, and BMI. This formula is non-invasive, requires no special equipment, and holds promise for practical application.

- Since adolescents accumulate sleep debt during weekdays and compensate for this debt on weekends or holidays, it is more practical to consider appropriate sleep time on a weekly rather than a daily basis.

- This review underscores the critical need for cultural transformation in Japan’s approach to sleep health, while also advocating for individualized sleep strategies to improve sleep health literacy.

- While this review highlights Bushidō-related values—such as self-sacrifice and asceticism—as cultural factors contributing to sleep deprivation in Japan, it is equally important to recognize the impact of contemporary influences, including electronic device use, academic pressure, and sedentary behavior. Addressing sleep deprivation among youth requires a comprehensive, multifactorial approach, and the present discussion offers one interpretive framework among many.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brain Sleep Inc. Fighting by Cutting Sleep—For Everyone. 17 June 2024. Available online: https://prtimes.jp/main/html/rd/p/000000205.000046684.html (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese).

- Keep Going Even When You’re Tired! Elementary and Middle School Students. Taisho Pharmaceutical Reconsiders the Copy for “Lipovitan Jr.”. 13 September 2016. Available online: https://www.j-cast.com/2016/09/13277863.html?p=all (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese).

- Yatsuzuka, E. Changes in Work Styles During the Heisei Era (Working Hours Edition): From “Can You Fight for 24 Hours?” to “Premium Friday” on 22 February 2019. Available online: https://news.yahoo.co.jp/expert/articles/a3ee57d86265d72d48593949023b83302226acc1 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Kohyama, J. Breaking Free from “Sacrificing Sleep to Achieve”: Toward an Approach Grounded in Sleep Health Literacy. J. Biosci. Med. 2025, 13, 359–377. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The 2024 Edition of the Health and Welfare White Paper. International Comparison of Sleep Duration. 2025. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/wp/hakusyo/kousei/23/backdata/01-01-01-23.html (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese)

- Mindell, J.A.; Sadeh, A.; Wiegand, B.; How, T.H.; Goh, D.Y. Cross-cultural differences in infant and toddler sleep. Sleep Med. 2010, 11, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindell, J.A.; Owens, J.; Alves, R.; Bruni, O.; Goh, D.Y.; Hiscock, H.; Kohyama, J.; Sadeh, A. Give children and adolescents the gift of a good night’s sleep: A call to action. Sleep Med. 2011, 12, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, J.A.; Weiss, M.R. Insufficient sleep in adolescents: Causes and consequences. Minerva Pediatr. 2017, 69, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohyama, J. Which Is More Important for Health: Sleep Quantity or Sleep Quality? Children 2021, 8, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Sun, Z.; Lin, F.; Xu, Y.; Wu, E.; Sun, X.; Zhou, X.; Wu, Y. Nonlinear relationships between sleep duration, mental health, and quality of life: The dangers of less sleep versus more sleep. Sleep Med. 2024, 119, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, D.; Shan, Z.; Lagopoulos, J.; Hermens, D.F. The role of adolescent sleep quality in the development of anxiety disorders: A neurobiologically-informed model. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 59, 101450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illingworth, G. The challenges of adolescent sleep. Interface Focus 2020, 10, 20190080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, E.C., Jr.; Mader, A.C.L.; Singh, P. Insufficient Sleep Syndrome: A Blind Spot in Our Vision of Healthy Sleep. Cureus 2022, 14, e30928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forthal, S.; Lin, S.; Cheslack-Postava, K. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Insufficient Sleep. Acad. Pediatr. 2025, 25, 102606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, O. Approach to a sleepy child: Diagnosis and treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in children and adolescents. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2023, 42, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambalis, K.D.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Psarra, G.; Sidossis, L.S. Insufficient Sleep Duration Is Associated With Dietary Habits, Screen Time, and Obesity in Children. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 1689–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sá, S.; Baião, A.; Marques, H.; Marques, M.D.C.; Reis, M.J.; Dias, S.; Catarino, M. The Influence of Smartphones on Adolescent Sleep: A Systematic Literature Review. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokka, I.; Mourikis, I.; Nicolaides, N.C.; Darviri, C.; Chrousos, G.P.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C.; Bacopoulou, F. Exploring the Effects of Problematic Internet Use on Adolescent Sleep: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez Zarate, R.; Colman, O.; Blake, S.C.; Watson, A.; Lee, Y.H.; Grooms, K.; Quader, Z.S.; Welsh, J.A.; Gazmararian, J.A. Factors That Influence Sleep Behaviors of High School Students: Findings From a Semi-Rural Community in Georgia. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohyama, J.; Ono, M.; Anzai, Y.; Kishino, A.; Tamanuki, K.; Moriyama, K.; Saito, Y.; Emoto, R.; Fuse, G.; Hatai, Y. Factors associated with sleep duration among pupils. Pediatr. Int. 2020, 62, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, J. Skipping breakfast is associated with lifestyle habits among Japanese pupils. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2021, 64, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Cao, M.; Sun, F.; Shi, B.; Wang, X.; Jing, J. Association Between Outdoor Activity and Insufficient Sleep in Chinese School-Aged Children. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e921617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macharla, N.K.; Palanichamy, C.; Thirunarayanan, M.; Suresh, M.; Ramachandran, A.S. Impact of Smartphone Usage on Sleep in Adolescents: A Clinically Oriented Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e76973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Y.; Wong, J.C.M.; Pereira, T.L.; Shorey, S. A qualitative systematic review of adolescent’s perceptions of sleep: Awareness of, barriers to and strategies for promoting healthy sleep patterns. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 4124–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruyt, K.; Chan, K.; Jayarathna, R.; Bruni, O. International Pediatric Sleep Association (IPSA) Pediatric Sleep Education Committee members. The need for pediatric sleep education to enhance healthcare for children and adolescents: A global perspective from a survey of members of the international pediatric sleep association. Sleep Med. 2025, 126, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.; Blunden, S.; BoydPratt, J.; Corkum, P.; Gebert, K.; Trenorden, K.; Rigney, G. Healthy sleep for healthy schools: A pilot study of a sleep education resource to improve adolescent sleep. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2022, 33 (Suppl. S1), 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illingworth, G.; Sharman, R.; Harvey, C.J.; Foster, R.G.; Espie, C.A. The Teensleep study: The effectiveness of a school-based sleep education programme at improving early adolescent sleep. Sleep Med. X 2020, 2, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigney, G.; Watson, A.; Gazmararian, J.; Blunden, S. Update on school-based sleep education programs: How far have we come and what has Australia contributed to the field? Sleep Med. 2021, 80, 134–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rijn, E.; Koh, S.Y.J.; Ng, A.S.C.; Vinogradova, K.; Chee, N.I.Y.N.; Lee, S.M.; Lo, J.C.; Gooley, J.J.; Chee, M.W.L. Evaluation of an interactive school-based sleep education program: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Sleep Health 2020, 6, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauducco, S.V.; Flink, I.K.; Boersma, K.; Linton, S.J. Preventing sleep deficit in adolescents: Long-term effects of a quasi-experimental school-based intervention study. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e12940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Li, S.X.; Zhang, J.H.; Lam, S.P.; Yu, M.W.M.; Tsang, C.C.; Kong, A.P.S.; Chan, K.C.C.; Li, A.M.; Wing, Y.K.; et al. School-Based Sleep Education Program for Children: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, N.Y.; Chen, S.J.; Ngan, C.L.; Li, S.X.; Zhang, J.; Lam, S.P.; Chan, J.W.Y.; Yu, M.W.M.; Chan, K.C.C.; Li, A.M.; et al. Advancing adolescent bedtime by motivational interviewing and text message: A randomized controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry, 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağlar, S.; Kesgin, M.T. The influence of sleep education supported and unsupported with social media reminders on the sleep quality in adolescents aged 14–18: A three-center, parallel-arm, randomized controlled study. Sleep Breath. 2024, 28, 2581–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.F.; Anderson, J.L.; Hodge, G.K. Use of a supplementary internet based education program improves sleep literacy in college psychology students. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013, 9, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, W.B.; Hijazi, H.; Radwan, H.; Saqan, R.; Al-Sharman, A.; Samsudin, A.B.R.; Fakhry, R.; Al-Yateem, N.; Rossiter, R.C.; Ibrahim, A.; et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of sleep hygiene education and FITBIT devices on quality of sleep and psychological worry: A pilot quasi-experimental study among first-year college students. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1182758. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin, C.J.; Venegas Hargous, C.; Stephens, L.D.; Nyam, G.; Brown, V.; Lander, N.; Yoong, S.; Morrissey, B.; Allender, S.; Strugnell, C. Sleep behavioral outcomes of school-based interventions for promoting sleep health in children and adolescents aged 5 to 18 years: A systematic review. Sleep Adv. 2024, 5, zpae019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Peng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Cai, S. A competition model for prediction of admission scores of colleges and universities in Chinese college entrance examination. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B. Back and Forth: History of College Admission in Korea. J. Educ. Soc. Policy 2022, 9, 78–86. Available online: https://jespnet.com/journals/Vol_9_No_2_June_2022/8.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Survey on Problems Related to Guidance on Problematic Behaviors and School Absence of Pupils. 2023. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20231004-mxt_jidou01-100002753_1.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese)

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Survey on Problems Related to Guidance on Problematic Behaviors and School Absence of Pupils. 2024. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20241031-mxt_jidou02-100002753_1_2.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese)

- Maeda, T.; Oniki, K.; Miike, T. Sleep Education in Primary School Prevents Future School Refusal Behavior. Paediatr. Int. 2019, 61, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuneya, T.; Sasahara, S.; Karube, H.; Handa, K.; Yakuwa, T. Tatenaka Power-Up Project: How Educational Programs Integrating Community and Family to Improve Lifestyle and Sleep Habits Enhanced Junior High School Students’ Morning Physical Condition and Self-Esteem. Yamagata Med. Assoc. J. 2021, 60, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The 2020 Edition of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare White Paper. 2021; p. 208. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000735866.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese)

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The 2024 Edition of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare White Paper. 2025; pp. 115–116. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/wp/hakusyo/kousei/23/dl/zentai.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese)

- NHK. Bureaucrats Screaming: What’s Happening at the Heart of Japan’s Government? 11 June 2024. Available online: https://www.nhk.jp/p/gendai/ts/R7Y6NGLJ6G/episode/te/8MJV8G3VRX/ (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Teacher Work Conditions Survey Aggregated Data [Preliminary Results]. 2023. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20230428-mxt_zaimu01-000029160_1.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese)

- Ludwig, R.; Eakman, A.; Bath-Scheel, C.; Siengsukon, C. How Occupational Therapists Assess and Address the Occupational Domain of Sleep: A Survey Study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 76, 7606345010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, A. Living with the Moon: Understanding the Moon and Following Its Rhythms; Revised Edition; Seibundou Shinkousha: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mother of Michitsuna. The Gossamer Years: A Diary by a Noblewoman of Heian Japan, 22nd ed.; Kadokawa Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2023; p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- National Astronomical Observatory of Japan Calendar Calculation (Long-Term Version). 1994. Available online: https://eco.mtk.nao.ac.jp/cgi-bin/koyomi/koyomiy_en.cgi (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese).

- Yamamoto, R. Early Rising; Kibosha: Osaka-shi, Japan, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara, T. Complete Translation of the Dongui Bogam by Heo Jun; Seishin Shuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Morishita, M. Yojokun in Modern Language by Ekiken Kaibara; Harashobou: Tokyo, Japan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Modern Translation of the Huangdi Neijing: Suwen, Volume I; Ishida, H.; Shimada, T.; Shoji, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Fujiyama, K., Translators; Nanjing College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Department of Classics of Chinese Medicine: Nanjing, China; Toyo Gakujutu Shuppan: Ichikawa, Janpan, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Insufficient sleep syndrome. In International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed.; Text Revision; Darien, I.L., Ed.; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2023; pp. 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, M. Sleep Duration and All-Cause Mortality. J. Insur. Med. 2025, 52, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Lond sleeper. In International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed.; Text Revision; Darien, I.L., Ed.; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2023; pp. 232–234. [Google Scholar]

- Kantermann, T.; Juda, M.; Merrow, M.; Roenneberg, T. The human circadian clock’s seasonal adjustment is disrupted by daylight saving time. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 1996–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetish, G.; Kaplan, H.; Gurven, M.; Wood, B.; Pontzer, H.; Manger, P.R.; Wilson, C.; McGregor, R.; Siegel, J.M. Natural sleep and its seasonal variations in three pre-industrial societies. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, 2862–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, M.V.; Kumar, S. Moon and Health: Myth or Reality? Cureus 2023, 15, e48491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röösli, M.; Jüni, P.; Braun-Fahrländer, C.; Brinkhof, M.W.; Low, N.; Egger, M. Sleepless night, the moon is bright: Longitudinal study of lunar phase and sleep. J. Sleep Res. 2006, 15, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casiraghi, L.; Spiousas, I.; Dunster, G.P.; McGlothlen, K.; Fernández-Duque, E.; Valeggia, C.; de la Iglesia, H.O. Moonstruck sleep: Synchronization of human sleep with the moon cycle under field conditions. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe0465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haba-Rubio, J.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Tobback, N.; Andries, D.; Preisig, M.; Kuehner, C.; Vollenweider, P.; Waeber, G.; Luca, G.; Tafti, M.; et al. Bad sleep? Don’t blame the moon! A population-based study. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitobe, I. Bushido: The Way of the Samurai in English and Japanese; Naramoto, T., Translator; Mikasashobo: Tokyo, Japan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga, T.; Kasuga, S.; Obata, M.; Obata, K. Kouyougunnkann, ed Yamada, H. 1893. Last Updated on 24 March 2024. Available online: https://ja.wikisource.org/wiki/%E7%94%B2%E9%99%BD%E8%BB%8D%E9%91%91 (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese).

- The Nursing History Research Group. A Family Guide for the Sick by Hirano, S. Modern Japanese Translation by Nosongyoson Bunka Kyokai Tokyo; Modern Japanese Translation by Nosongyoson Bunka Kyokai: Tokyo, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, M. Takizawa Bakin—Letters and People; Yagi-Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Iyo Historical Society. A Diary of a Uwajima Clan Samurai in Edo. 18 January 2011; Volume 1. Available online: https://iyosidan.jugem.jp/?eid=37 (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese).

- Lyricist Unknow. The Village Blacksmith. Last Updated on 16 March 2024. Available online: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%9D%91%E3%81%AE%E9%8D%9B%E5%86%B6%E5%B1%8B (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese).

- Lyricist Unknow. Kinjiro Ninomiya (Elementary School Choral Songs). Updated on 12 October 2021. Available online: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%BA%8C%E5%AE%AE%E9%87%91%E6%AC%A1%E9%83%8E_(%E5%94%B1%E6%AD%8C) (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese).

- Sakamoto, S. Children’s ‘Work’ Ethics in Meiji Morality Textbooks—Kinjiro Ninomiya and Tasuke Shiobara. Issues Lang. Cult. 2012, 13, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shonan High School Anthem and Fight Song. Song of Youth. 2006. Available online: http://www.shoyukai.org/music-cd/cd.html (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese).

- Lau, J.; Mychasuk, E.; Terazono, E.; Nippon Sheet Glass Chief to Step Down. Financial Times, 27 August 2009. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/d33b8850-92b4-11de-b63b-00144feabdc0 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Kawato, H.; Kanie, K. The Implications of the Dentsu Overwork Death Incident. DIO 2017, 324, 8–11. Available online: https://www.rengo-soken.or.jp/dio/dio324-2.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025). (In Japanese).

- Fukazawa, Y. You Might Be Pushing Someone to Their Breaking Point. AERA, 21 November 2016; pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sports Agency. Report on the 2017 Survey of the Actual Conditions of Sports Club Activities, etc. 2018, Tokyo Shoseki. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/sports/b_menu/sports/mcatetop04/list/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2018/06/12/1403173_2.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Miura, I. Why Japanese People Have Become Self-Sacrificing Workers and What to Do About It. Available online: https://note.com/ipmiura/n/n416344b914bd (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Campbell, I.G.; Kurinec, C.A.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Cruz-Basilio, A.; Figueroa, J.G.; Bottom, V.B.; Whitney, P.; Hinson, J.M.; Van Dongen, H.P.A. Sleep restriction and age effects on distinct aspects of cognition in adolescents. Sleep 2024, 47, zsae216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orna, T.; Efrat, B. Sleep Loss, Daytime Sleepiness, and Neurobehavioral Performance among Adolescents: A Field Study. Clocks Sleep. 2022, 4, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.; Di Biase, M.A.; Bei, B.; Quach, J.; Cropley, V. Associations of Changes in Sleep and Emotional and Behavioral Problems From Late Childhood to Early Adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claussen, A.H.; Dimitrov, L.V.; Bhupalam, S.; Wheaton, A.G.; Danielson, M.L. Short Sleep Duration: Children’s Mental, Behavioral, and Developmental Disorders and Demographic, Neighborhood, and Family Context in a Nationally Representative Sample, 2016–2019. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2023, 20, E58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, H.; Xiao, Q.; Wu, Q.; Jin, Y.; Liu, T.; Liu, D.; Cui, C.; Dong, X. Association between excessive screen time and falls, with additional risk from insufficient sleep duration in children and adolescents, a large cross-sectional study in China. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1452133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, A.A.; Zoubeidi, T. Association of overweight, obesity and insufficient sleep duration and related lifestyle factors among school children and adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2021, 34, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, M.; Hinnant, J.B.; Philbrook, L.E. Trajectories of sleep and cardiac sympathetic activity indexed by pre-ejection period in childhood. J. Sleep Res. 2017, 26, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaVoy, E.C.; Palmer, C.A.; So, C.; Alfano, C.A. Bidirectional relationships between sleep and biomarkers of stress and immunity in youth. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2020, 158, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cespedes, E.M.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Redline, S.; Gillman, M.W.; Peña, M.M.; Taveras, E.M. Longitudinal associations of sleep curtailment with metabolic risk in mid-childhood. Obesity 2014, 22, 2586–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maric, A.; Montvai, E.; Werth, E.; Storz, M.; Leemann, J.; Weissengruber, S.; Ruff, C.C.; Huber, R.; Poryazova, R.; Baumann, C.R. Insufficient sleep: Enhanced risk-seeking relates to low local sleep intensity. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 82, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, J. Re-Evaluating Recommended Optimal Sleep Duration: A Perspective on Sleep Literacy. Children 2024, 11, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshkowitz, M.; Whiton, K.; Albert, S.M.; Alessi, C.; Bruni, O.; DonCarlos, L.; Hazen, N.; Herman, J.; Katz, E.S.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L.; et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health 2015, 1, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paruthi, S.; Brooks, L.J.; D’Ambrosio, C.; Hall, W.A.; Kotagal, S.; Lloyd, R.M.; Malow, B.A.; Maski, K.; Nichols, C.; Quan, S.F.; et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: A consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2016, 12, 785–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sleep and Sleep Disorders in Children. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/ (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Kohyama, J. Formula for Calculating Optimal Sleep Duration in Adolescents. Am. J. Med. Clin. Res. Rev. 2025, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, J. A proposal on the novel method to estimate optimal sleep duration based on self-reported survey data. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, J. Adolescents with difficulty in morning awakening: Current knowledge, care plan and future problems from a sleep medicine viewpoint. No To Hattatsu 2023, 55, 413–420. [Google Scholar]

- Taheri, S.; Lin, L.; Austin, D.; Young, T.; Mignot, E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004, 1, e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, P.; Putois, B.; Guyon, A.; Raoux, A.; Papadopoulou, M.; Guignard-Perret, A.; Bat-Pitault, F.; Hartley, S.; Plancoulaine, S. Sleep during development: Sex and gender differences. Sleep Med. Rev. 2020, 51, 101276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenson, J.C.; Williamson, A.A. Bridging the gap: Leveraging implementation science to advance pediatric behavioral sleep interventions. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2023, 19, 1321–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, X.; Chen, Z. Frequency of Vigorous physical activity and sleep difficulty in adolescents: A multiply-country cross-sectional study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2024, 55, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, D.; Sosso, F.A.E. Socioeconomic status and sleep health: A narrative synthesis of 3 decades of empirical research. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2023, 19, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, A.W.; Ralston, P.A.; Young-Clark, I.; Coccia, C.C. Life Satisfaction and Emerging Health Behaviors in Underserved Adolescents: A Narrative Review. Am. J. Health Behav. 2023, 47, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guindon, G.E.; Murphy, C.A.; Milano, M.E.; Seggio, J.A. Turn off that night light! Light-at-night as a stressor for adolescents. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1451219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, P.L.; Mainster, M.A. Circadian photoreception: Aging and the eye’s important role in systemic health. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 92, 1439–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, Y. The Current Situation of “the Image of Devoted Teacher” Among Japanese School Teachers. Ryukyu Univ. Grad. Sch. Educ. J. 2021, 5, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kamara, D.; Bernard, A.; Clark, E.L.M.; Duraccio, K.M.; Ingram, D.G.; Li, T.; Piper, C.R.; Cooper, E.; Simon, S.L. Systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for sleep disruption in pediatric neurodevelopmental and medical conditions. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Haegele, J.A.; Tse, A.C.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, S.; Li, S.X. The impact of the physical activity intervention on sleep in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2024, 74, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, D.; Belli, A.; Ferri, R.; Bruni, O. Sleeping without Prescription: Management of Sleep Disorders in Children with Autism with Non-Pharmacological Interventions and Over-the-Counter Treatments. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Step | Goal | Explanation | Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acquiring knowledge about the detrimental effects of sleep deprivation | This is similar to the basics of widely implemented programs. | Easy |

| 2 | Achieving personal relevance regarding the harms of sleep | It is difficult to reach this awareness with step 1 alone. In such cases, consider progressing to step 3. | Hard |

| 3 | Understanding three simple indicators of sleep deprivation | As these are concrete indicators, they can serve as significant triggers for self-awareness of sleep deprivation. | Slightly hard |

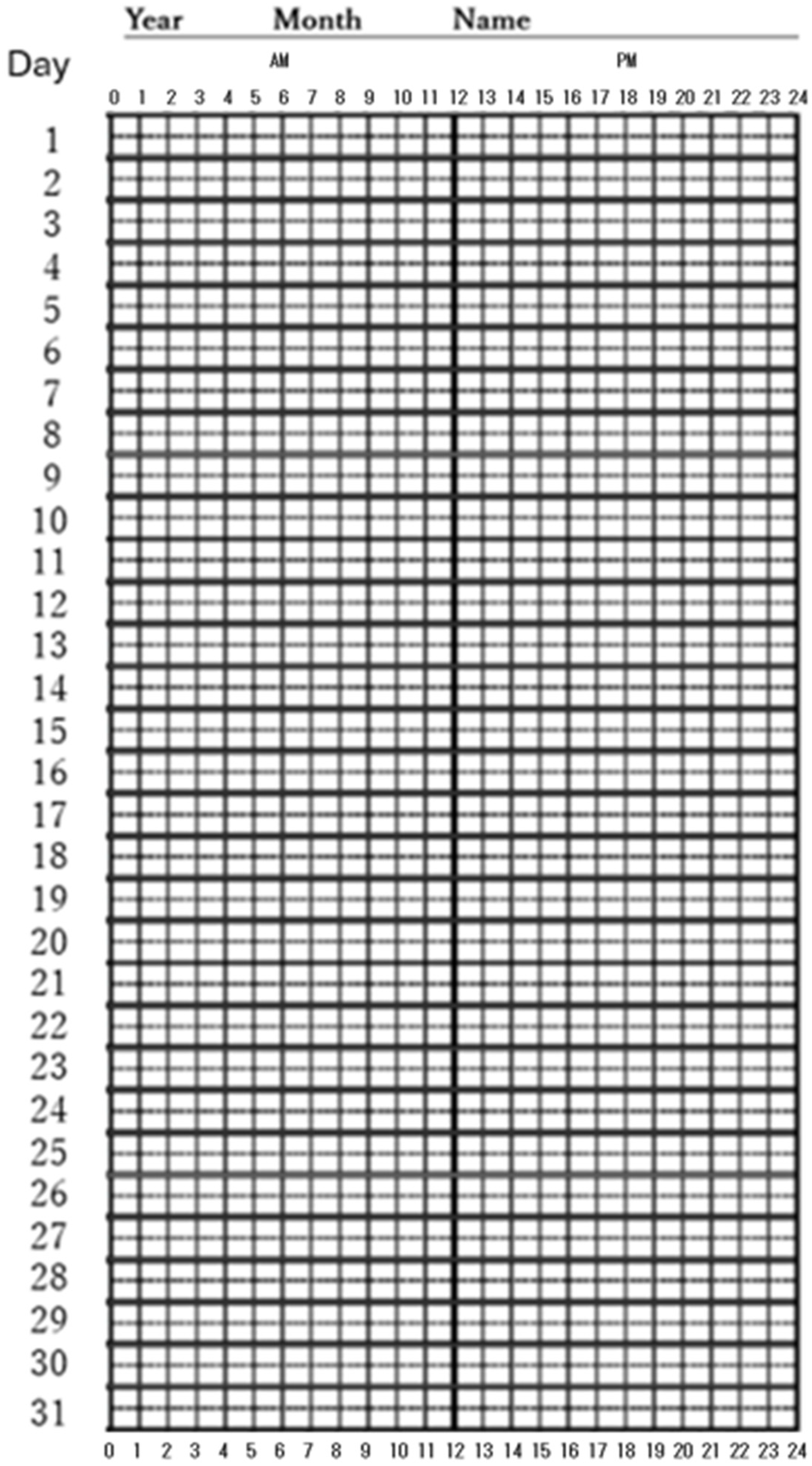

| 4 | Monitoring one’s own sleep duration | This is a step further after step 3. Once this step is reached, problem-solving is within sight. | Relatively easy, if step 3 is cleared |

| 5 | Confirming step 2 | After recognizing one’s optimal sleep duration on a weekly basis, the abnormality of previous sleep patterns can be recognized more strongly and impressively. This step further reinforces self-awareness regarding the issues of sleep deprivation. | Easy |

| National Sleep Foundation [89] | American Academy of Sleep Medicine [90] | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [91] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | MBA | Rec | MBA | Age | Rec | Age | Rec |

| 6–13 | 7–8≤ | 9–11 | ≤12 | 6–12 | 9–12 | 6–12 | 9–12 |

| 14–17 | 7≤ | 8–10 | ≤11 | 13–18 | 8–10 | 13–17 | 8–10 |

| 18–25 | 6≤ | 7–9 | ≤10–11 | 18–60 | 7 or more | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kohyama, J. Cultural Approaches to Addressing Sleep Deprivation and Improving Sleep Health in Japan: Sleep Issues Among Children and Adolescents Rooted in Self-Sacrifice and Asceticism. Children 2025, 12, 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050566

Kohyama J. Cultural Approaches to Addressing Sleep Deprivation and Improving Sleep Health in Japan: Sleep Issues Among Children and Adolescents Rooted in Self-Sacrifice and Asceticism. Children. 2025; 12(5):566. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050566

Chicago/Turabian StyleKohyama, Jun. 2025. "Cultural Approaches to Addressing Sleep Deprivation and Improving Sleep Health in Japan: Sleep Issues Among Children and Adolescents Rooted in Self-Sacrifice and Asceticism" Children 12, no. 5: 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050566

APA StyleKohyama, J. (2025). Cultural Approaches to Addressing Sleep Deprivation and Improving Sleep Health in Japan: Sleep Issues Among Children and Adolescents Rooted in Self-Sacrifice and Asceticism. Children, 12(5), 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12050566