Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria: Improvements in Arterial Stiffness and Bone Mineral Density in a Single Case

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Report

2.1. Case Description

2.2. Study Design

3. Results

3.1. Improvements in Body Composition, Bone Mineral Density, and Dentition

3.2. Amelioration of Stiffness: Joints, Tympanic Membrane, and Arterial Flexibility

3.3. Short-Term Improvement in Growth and Metabolic Aspects

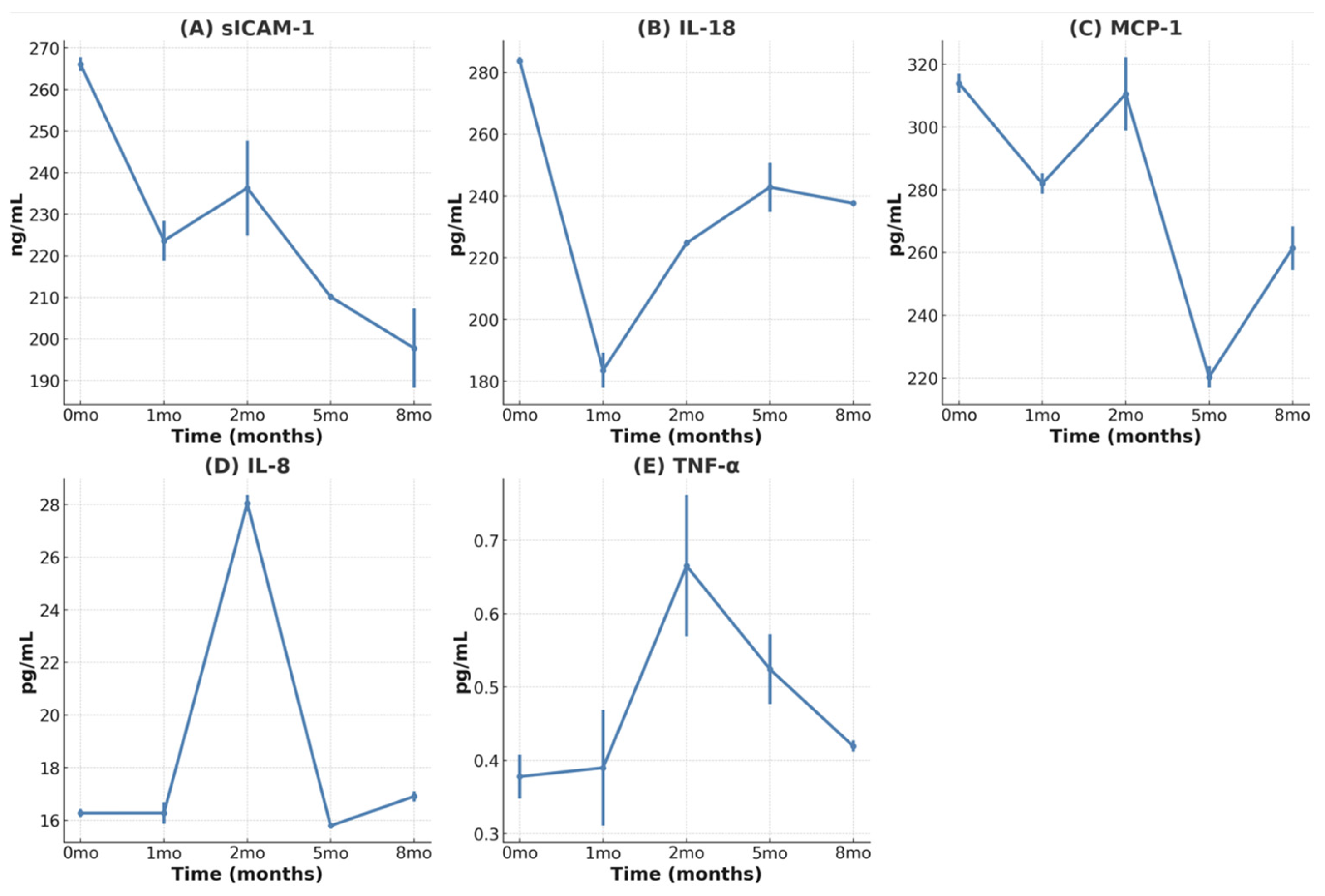

3.4. Reduction in Inflammatory Cytokines

3.5. Lower Efficacy for Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Aspects

3.6. Safety of MSC Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Literature Review

| Year Authors | Subjects | Methodology | Key Findings | Mechanism | Clinical Implications | Limitations/Future Directions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 [40] Scaffidi P et al. | hMSC | Expression of progerin in hMSCs; analysis of stem cell function | Discovered misregulation leading to premature aging | Progerin interferes with the function of hMSCs | Progerin activates Notch signaling pathway in hMSCs | Limited to in vitro study: in vivo confirmation needed |

| 2011 [41] Zhang J, et al. | iPSC-derived cells | iPSC differentiation and analysis | Vascular smooth muscle and mesenchymal stem cell defects identified | iPSCs reveal specific cellular defects in HGPS | New targets for therapeutic intervention | Validation in patient samples required |

| 2011 [42] Liu et al. | HGPS patient fibroblasts | Generation of iPSCs from HGPS fibroblasts; Differentiation of iPSCs | iPSCs from HGPS patients lack progerin expression but resume upon differentiation | Reprogramming suppresses progerin expression: differentiation resumes aging-associated phenotypes | iPSCs as a model for studying HGPS and drug screening | Limited to in vitro model: in vivo validation needed |

| 2011 [19] Rosengardten Y et al. | HGPS mouse model | Analysis of stem cell populations and wound healing capacity | HGPS mutation causes adult stem cell depletion and impaired wound healing | Progerin accumulation leads to stem cell exhaustion | Stem cell therapies may be beneficial for HGPS patients | Limited to mouse model: human studies needed |

| 2012 [44] Lavasani M et al. | Progeroid mice | Intraperitoneal injection of young wild-type MDSPCs | Extended lifespan and healthspan of progeroid mice | Secretion of factors by MDSPCs that improve tissue function | Stem cell transplantation as potential therapy for progeria | Limited to animal model: human studies needed |

| 2015 [43] Lo Cicero A, Nissan X | iPSCs | iPSC modeling of HGPS | Improved understanding of disease mechanisms | iPSCs recreate HGPS cellular environment for study | Improved drug screening platform | Translation to in vivo models needed |

| 2020 [29] Park J et al. | HGPS patient | adipose SVF containing MSC | Increased height, weight and IGF-1 | anti-inflammatory effects via paracrine signaling | Proposal for the potential treatment of inflammaging-related diseases | Single case study: larger trials needed |

| 2021 [30] Suh YS, et al. | HGPS patient | Cord blood stem cell infusion +sirolimus | Improved growth, reduced PWV, slowed IMT progression | Cord blood stem cells may provide trophic support and replace damaged cells | Potential noninvasive treatment for HGPS | Single case study: larger trials needed |

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Sandre-Giovannoli, A.; Bernard, R.; Cau, P.; Navarro, C.; Amiel, J.; Boccaccio, I.; Lyonnet, S.; Stewart, C.L.; Munnich, A.; Le Merrer, M.; et al. Lamin a truncation in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria. Science 2003, 300, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, M.; Brown, W.T.; Gordon, L.B.; Glynn, M.W.; Singer, J.; Scott, L.; Erdos, M.R.; Robbins, C.M.; Moses, T.Y.; Berglund, P. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature 2003, 423, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, T.; Romiti, R. Progeria infantum (Hutchinson–Gilford syndrome) associated with scleroderma-like lesions and acro-osteolysis: A case report and brief review of the literature. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2000, 17, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rork, J.F.; Huang, J.T.; Gordon, L.B.; Kleinman, M.; Kieran, M.W.; Liang, M.G. Initial cutaneous manifestations of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014, 31, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennekam, R.C. Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome: Review of the phenotype. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2006, 140, 2603–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merideth, M.A.; Gordon, L.B.; Clauss, S.; Sachdev, V.; Smith, A.C.; Perry, M.B.; Brewer, C.C.; Zalewski, C.; Kim, H.J.; Solomon, B.; et al. Phenotype and course of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.B.; McCarten, K.M.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Machan, J.T.; Campbell, S.E.; Berns, S.D.; Kieran, M.W. Disease progression in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome: Impact on growth and development. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevado, R.M.; Hamczyk, M.R.; Gonzalo, P.; Andres-Manzano, M.J.; Andres, V. Premature Vascular Aging with Features of Plaque Vulnerability in an Atheroprone Mouse Model of Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome with Ldlr Deficiency. Cells 2020, 9, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Mojiri, A.; Boulahouache, L.; Morales, E.; Walther, B.K.; Cooke, J.P. Vascular senescence in progeria: Role of endothelial dysfunction. Eur. Heart J. Open 2022, 2, oeac047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.B.; Massaro, J.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Campbell, S.E.; Brazier, J.; Brown, W.T.; Kleinman, M.E.; Kieran, M.W.; Progeria Clinical Trials, C. Impact of farnesylation inhibitors on survival in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Circulation 2014, 130, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Gordon, L.B.; Kleinman, M.E.; Gurary, E.B.; Massaro, J.; D’Agostino, R., Sr.; Kieran, M.W.; Gerhard-Herman, M.; Smoot, L. Cardiac Abnormalities in Patients With Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, L.B.; Shappell, H.; Massaro, J.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Brazier, J.; Campbell, S.E.; Kleinman, M.E.; Kieran, M.W. Association of Lonafarnib Treatment vs No Treatment With Mortality Rate in Patients With Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome. JAMA 2018, 319, 1687–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M.; Jeng, L.J.B.; Chefo, S.; Wang, Y.; Price, D.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Li, R.J.; Ma, L.; Yang, Y.; et al. FDA approval summary for lonafarnib (Zokinvy) for the treatment of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome and processing-deficient progeroid laminopathies. Genet Med. 2023, 25, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.B.; Kleinman, M.E.; Miller, D.T.; Neuberg, D.S.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Gerhard-Herman, M.; Smoot, L.B.; Gordon, C.M.; Cleveland, R.; Snyder, B.D.; et al. Clinical trial of a farnesyltransferase inhibitor in children with Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16666–16671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.B.; Kleinman, M.E.; Massaro, J.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Shappell, H.; Gerhard-Herman, M.; Smoot, L.B.; Gordon, C.M.; Cleveland, R.H.; Nazarian, A.; et al. Clinical Trial of the Protein Farnesylation Inhibitors Lonafarnib, Pravastatin, and Zoledronic Acid in Children With Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome. Circulation 2016, 134, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutaleb, N.O.; Atchison, L.; Choi, L.; Bedapudi, A.; Shores, K.; Gete, Y.; Cao, K.; Truskey, G.A. Lonafarnib and everolimus reduce pathology in iPSC-derived tissue engineered blood vessel model of Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaschek-Wiener, J.; Brooks-Wilson, A. Progeria of stem cells: Stem cell exhaustion in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridger, J.M.; Kill, I.R. Aging of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome fibroblasts is characterised by hyperproliferation and increased apoptosis. Exp. Gerontol. 2004, 39, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengardten, Y.; McKenna, T.; Grochova, D.; Eriksson, M. Stem cell depletion in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolla, T.A. Multiple roads to the aging phenotype: Insights from the molecular dissection of progerias through DNA microarray analysis. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2005, 126, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowska, S.; Andrzejewska, A.; Janowski, M.; Lukomska, B. Immunomodulatory and Regenerative Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Extracellular Vesicles: Therapeutic Outlook for Inflammatory and Degenerative Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 591065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Ge, J.; Huang, C.; Liu, H.; Jiang, H. Application of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for aging frailty: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5675–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogay, V.; Sekenova, A.; Li, Y.; Issabekova, A.; Saparov, A. The Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 16, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwin, T.; Gomes, A.; Amin, R.; Sufi, A.; Goswami, S.; Wang, B. Mechanisms underlying the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in atherosclerosis. RegenMed 2021, 16, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, N.; Hong, H.; Qi, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Therapeutic Mechanisms for Stroke. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.L.; Yet, S.F.; Hsu, Y.T.; Wang, G.J.; Hung, S.C. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorate Atherosclerotic Lesions via Restoring Endothelial Function. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015, 4, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drole Torkar, A.; Plesnik, E.; Groselj, U.; Battelino, T.; Kotnik, P. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Healthy Children and Adolescents: Normative Data and Systematic Literature Review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 597768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, W.A.; Stephan, C.; Terajima, M.; Thaivalappil, A.A.; Blanchard, O.; Tavarez, U.L.; Narisu, N.; Yan, T.; Wincovitch, S.M.; Taga, Y.; et al. Bone dysplasia in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome is associated with dysregulated differentiation and function of bone cell populations. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e13903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, J.; Lee, J.H.; Jeon, J.H.; Kim, Y.B.; Jeong, B.C.; Lee, S.H. Potential Benefits of Allogeneic Haploidentical Adipose Tissue-Derived Stromal Vascular Fraction in a Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome Patient. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 574010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, M.R.; Lim, I.; Kim, J.; Yang, P.S.; Choung, J.S.; Sim, H.R.; Ha, S.C.; Kim, M. Efficacy of Cord Blood Cell Therapy for Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome-A Case Report. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtada, S.I.; Mikush, N.; Wang, M.; Ren, P.; Kawamura, Y.; Ramachandra, A.B.; Li, D.S.; Braddock, D.T.; Tellides, G.; Gordon, L.B.; et al. Lonafarnib improves cardiovascular function and survival in a mouse model of Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Elife 2023, 12, e82728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, F.J.; Gordon, L.B.; Smoot, L.; Kleinman, M.E.; Gerhard-Herman, M.; Hegde, S.M.; Mukundan, S.; Mahoney, T.; Massaro, J.; Ha, S.; et al. Progression of Cardiac Abnormalities in Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Circulation 2023, 147, 1782–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, J.K.; Rehsia, S.K.; Verma, E.; Sareen, N.; Dhingra, S. Stem cell therapy for cardiac regeneration: Past, present, and future. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2024, 102, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavellina, D.; Balkan, W.; Hare, J.M. Stem cell therapy for acute myocardial infarction: Mesenchymal Stem Cells and induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2023, 23, 951–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Seo, S.; Song, E.J.; Kweon, O.; Jo, A.H.; Park, S.; Woo, T.G.; Kim, B.H.; Oh, G.T.; Park, B.J. Progerinin, an Inhibitor of Progerin, Alleviates Cardiac Abnormalities in a Model Mouse of Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome. Cells 2023, 12, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdos, M.R.; Cabral, W.A.; Tavarez, U.L.; Cao, K.; Gvozdenovic-Jeremic, J.; Narisu, N.; Zerfas, P.M.; Crumley, S.; Boku, Y.; Hanson, G.; et al. A targeted antisense therapeutic approach for Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sougawa, Y.; Miyai, N.; Utsumi, M.; Miyashita, K.; Takeda, S.; Arita, M. Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in healthy Japanese adolescents: Reference values for the assessment of arterial stiffness and cardiovascular risk profiles. Hypertens. Res. 2020, 43, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Kaur, R.; Kumari, P.; Pasricha, C.; Singh, R. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1: Gatekeepers in various inflammatory and cardiovascular disorders. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 548, 117487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.M.; Wiesolek, H.L.; Sumagin, R. ICAM-1: A master regulator of cellular responses in inflammation, injury resolution, and tumorigenesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 108, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaffidi, P.; Misteli, T. Lamin A-dependent misregulation of adult stem cells associated with accelerated ageing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lian, Q.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, F.; Sui, L.; Tan, C.; Mutalif, R.A.; Navasankari, R.; Zhang, Y.; Tse, H.F.; et al. A human iPSC model of Hutchinson Gilford Progeria reveals vascular smooth muscle and mesenchymal stem cell defects. Cell Stem. Cell 2011, 8, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.H.; Barkho, B.Z.; Ruiz, S.; Diep, D.; Qu, J.; Yang, S.L.; Panopoulos, A.D.; Suzuki, K.; Kurian, L.; Walsh, C.; et al. Recapitulation of premature ageing with iPSCs from Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature 2011, 472, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Cicero, A.; Nissan, X. Pluripotent stem cells to model Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS): Current trends and future perspectives for drug discovery. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 24, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavasani, M.; Robinson, A.R.; Lu, A.; Song, M.; Feduska, J.M.; Ahani, B.; Tilstra, J.S.; Feldman, C.H.; Robbins, P.D.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; et al. Muscle-derived stem/progenitor cell dysfunction limits healthspan and lifespan in a murine progeria model. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, E.; Lee, J. Current Therapeutic Approaches for Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome. J. Interdiscip. Genomics 2025, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

| −2 Years | Baseline | 2 Months | 5 Months | 8 Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Treatment | 1 Month After 2nd MSC | 3 Months After 3rd MSC | 6 Months After 3rd MSC | |||

| Growth | Height (cm) z-score for height | 93.2 −4.65 | 101.2 −5.41 | 102.1 −5.41 | 102.2 −5.46 | 103 −5.73 |

| Weight (kg) z-score for weight | 11.6 −5.56 | 12.1 −6.89 | 12.6 −6.48 | 12.7 −6.3 | 13 −6.14 | |

| ALP (U/L) (ref: 120–344) | 178 | 207 | 218 | 166 | 207 | |

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) (ref: 90.6–268.8) | 145.5 | 173.1 | 235.6 | 118 | 104.4 | |

| z-score for IGF-1 | −0.15 | 0.03 | 1.32 | −1.24 | −1.49 | |

| IGFBP3 (ng/mL) (ref: 1620–3490) | 1446 | 1786 | 2664 | 2608 | 2147 | |

| z-score for IGFBP3 | −1.96 | −1.6 | 0.37 | −0.04 | −0.96 | |

| Metabolic | HbA1c (%) | 5.8 | 5.5 | 5.9 | 5.8 | |

| AST/ALT (U/L) | 31/22 | 34/35 | 38/38 | 31/41 | 34/45 | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 219 | 180 | 165 | 149 | 115 | |

| Cardiac | CK-MB (normal 0–5 ng/mL) | 4.2 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 3.2 |

| D-dimer (normal 0–0.5 μg/mL) | 1.67 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.28 | ||

| BP (systolic/diastolic) | 99/69 | 100/47 | 104/51 | 100/52 | 117/60 | |

| BaPWV (cm/s) rt/lt | 1113/1228 | 1011/1097 | ||||

| cIMT mean (mm) rt/lt | 0.43/0.36 | 0.47/0.46 | 0.61/0.51 | |||

| max (mm) rt/lt | 0.60/0.52 | 0.60/0.68 | 0.80/0.68 | |||

| TTE-TDI e’ (cm/s (z-score)) E/e (normal < 8) | 7 (−4.04) | 8 (−3.53) 16.1 | 5.89 (−4.6) 12.28 | |||

| EF (normal 50–70%) | 64.36 | 70 | 62.7 | 56.2 | ||

| FS (normal 25–45%) | 34.38 | 40 | 33.18 | 28.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joo, E.-Y.; Park, J.-S.; Shin, H.-T.; Yoo, M.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, J.-E.; Choi, G.-S. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria: Improvements in Arterial Stiffness and Bone Mineral Density in a Single Case. Children 2025, 12, 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040523

Joo E-Y, Park J-S, Shin H-T, Yoo M, Kim S-J, Lee J-E, Choi G-S. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria: Improvements in Arterial Stiffness and Bone Mineral Density in a Single Case. Children. 2025; 12(4):523. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040523

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoo, Eun-Young, Ji-Sun Park, Hyun-Tae Shin, Myungji Yoo, Su-Jin Kim, Ji-Eun Lee, and Gwang-Seong Choi. 2025. "Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria: Improvements in Arterial Stiffness and Bone Mineral Density in a Single Case" Children 12, no. 4: 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040523

APA StyleJoo, E.-Y., Park, J.-S., Shin, H.-T., Yoo, M., Kim, S.-J., Lee, J.-E., & Choi, G.-S. (2025). Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria: Improvements in Arterial Stiffness and Bone Mineral Density in a Single Case. Children, 12(4), 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040523