Treatment Access and Caregiver Experience in Pediatric Rhabdomyosarcoma: Results of an Online Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

- −

- “How many delays there would be”

- −

- “That our HMO would provide care outside of our institution, due the rarity of her diagnosis and lack of familiarity with her disease among local clinicians”

- −

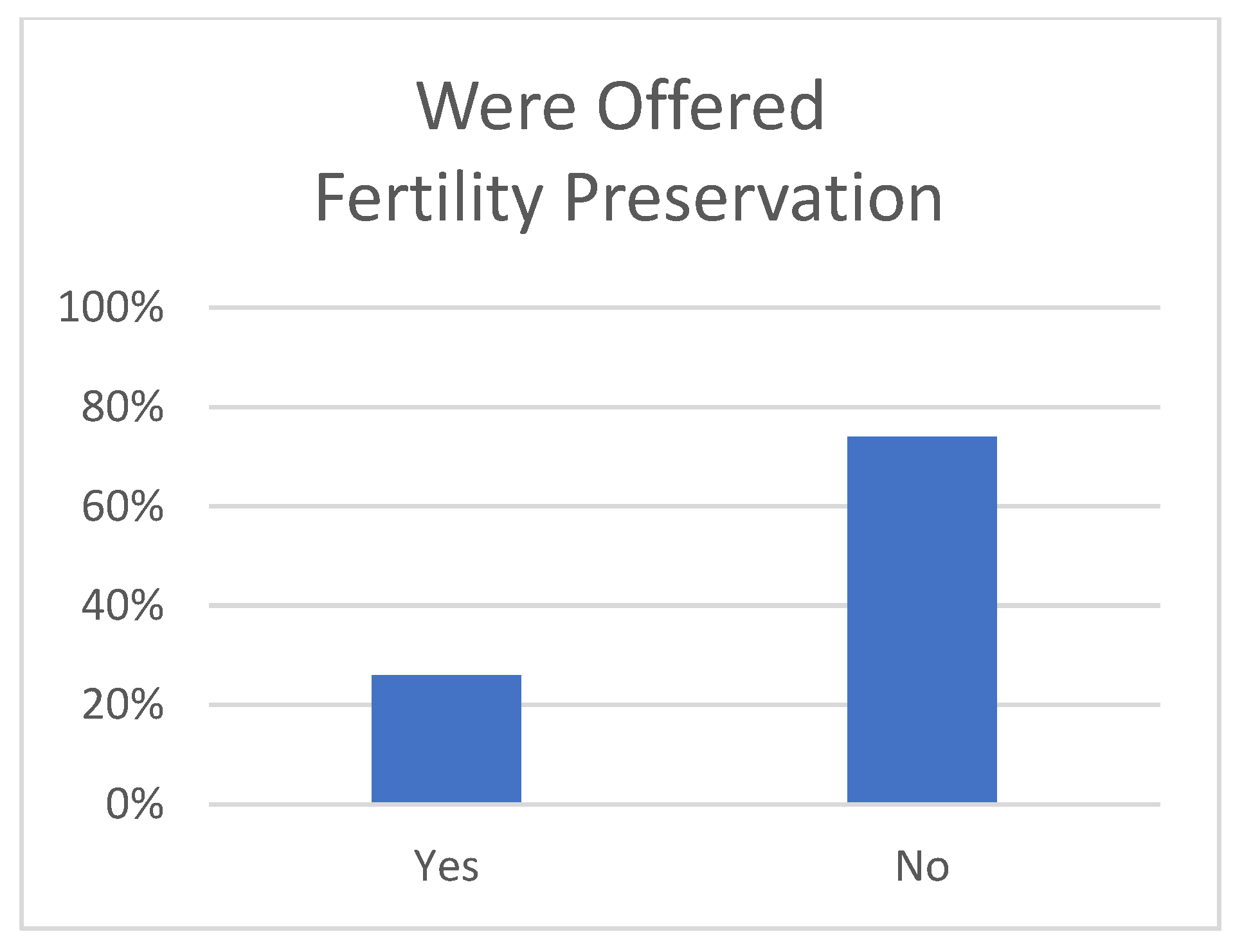

- “To preserve her reproductive organs”

- −

- “Go to a Sarcoma center. Send tissue off to a Rhabdo specialist.”

- −

- “Do your research! Get a second or even third opinion!”

- −

- “I wish I had known about rhabdo specialists.”

- −

- “It’s an art, not a science.”

- −

- “I wish we would have tried resection when it came back. It’s like the docs gave up. That was never offered as an option.”

- −

- “The pediatric rhabdo Facebook group”

- −

- “The different treatment options available abroad”

- −

- “Ask questions and do not assume that the doctors are doing everything possible to save the patient. The earlier you act, the better. Seek a second opinion.”

- −

- “Push the pediatrician! She put us off for months and my daughter was stage 3 when she could have been treated much earlier.”

- −

- “Insist surgery and radiation—more aggressive treatment.”

- −

- “I wish I would have known about fertility preservation.”

- −

- “Go to the right doctor immediately and push doctors to be more aggressive and quicker in treatments! It’s such an aggressive and quick cancer and some doctors drag their feet too much.”

- −

- “Don’t listen blindly to the health care professionals. Ask questions and engage in discussions to understand better the decisions being taken, their consequences, and the options available.”

- −

- “I would have traveled for a second opinion.”

- −

- “Make sure you are talking with a sarcoma specialist.”

- −

- “I wish I would have done more research and been a better advocate for my son.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

- The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| pRMS | Pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma |

References

- Gloeckler Ries, L.A.; Reichman, M.E.; Lewis, D.R.; Hankey, B.F.; Edwards, B.K. Cancer survival and incidence from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Oncologist 2003, 8, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effendy, C.; Uligraff, D.K.; Sari, S.H.; Angraini, F.; Chandra, L. Experiences of family caregivers of children with cancer while receiving home-based pediatric palliative care in Indonesia: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismael, N.; Jaber, A.; Malkawi, S.; Al Awady, S.; Ismael, T. Exploring coping strategies among caregivers of children who have survived paediatric cancer in Jordan. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2024, 8, e002453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsavsky, A.L.; Sutherland-Foggio, M.; Stanek, C.J.; Hill, K.N.; Himelhoch, A.C.; Kenney, A.E.; Humphrey, L.; Olshefski, R.; Skeens, M.A.; Nahata, L.; et al. Factors associated with caregiver strain among mothers and fathers of children with advanced cancer. Palliat. Support. Care 2024, 22, 2060–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papyan, R.; Tamamyan, G.; Danielyan, S.; Tananyan, A.; Muradyan, A.; Saab, R. Identifying barriers to treatment of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma in resource-limited settings: A literature review. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadinov, K.; Iskrov, G.; Musurlieva, N.; Stefanov, R. An Evaluation of Rare Cancer Policies in Europe: A Survey Among Healthcare Providers. Cancers 2025, 17, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Reinke, D.; van Oortmerssen, G.; Gonzato, O.; Ott, G.; Raut, C.P.; Guadagnolo, B.A.; Haas, R.L.M.; Trent, J.; Jones, R.; et al. What Is a Sarcoma ‘Specialist Center’? Multidisciplinary Research Finds an Answer. Cancers 2024, 16, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, N.M.; Devansyah, S.; Modjaningrat, I.; Suryawan, N.; Susanah, S.; Rakhmillah, L.; Wahyudi, K.; Kaspers, G.J.L. Type of cancer and complementary and alternative medicine are determinant factors for the patient delay experienced by children with cancer: A study in West Java, Indonesia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2023, 70, e30192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winestone, L.E.; Wilkes, J.J.; Puccetti, D.; Keegan, T.H.M.; Henk, H.J.; McPheeters, J.; Kahn, J.M.; Ginsberg, J.; Wong, S.; Timberline, S.; et al. Time to diagnosis among young patients with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2024, 71, e30997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombe, D.C.; Mwamba, M.; Msadabwe, S.; Bond, V.; Simwinga, M.; Ssemata, A.S.; Muhumuza, R.; Seeley, J.; Mwaka, A.D.; Aggarwal, A. Delays in seeking, reaching and access to quality cancer care in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappy, M.; Lieman, H.J.; Pollack, S.; Buyuk, E. Fertility preservation for cancer patients: Treatment gaps and considerations in patients’ choices. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 303, 1617–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meernik, C.; Engel, S.M.; Baggett, C.D.; Wardell, A.; Zhou, X.; Ruddy, K.J.; Wantman, E.; Baker, V.L.; Luke, B.; Mersereau, J.E.; et al. Time to cancer treatment and reproductive outcomes after fertility preservation among adolescent and young adult women with cancer. Cancer 2023, 129, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doungkamchan, C.; Orwig, K.E. Recent advances: Fertility preservation and fertility restoration options for males and females. Fac. Rev. 2021, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordechai, O.; Tamir, S.; Weyl-Ben-Arush, M. Seeking a second opinion in pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 32, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.; Hanaya, H.; Seilacher, E.; Koester, M.-J.; Keinki, C.; Liebl, P.; Huebner, J. Information Deficits and Second Opinion Seeking—A Survey on Cancer Patients. Cancer Investig. 2017, 35, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peier-Ruser, K.S.; von Greyerz, S. Why Do Cancer Patients Have Difficulties Evaluating the Need for a Second Opinion and What Is Needed to Lower the Barrier? A Qualitative Study. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2018, 41, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.W.; Cho, J.; Yang, H.K.; Kim, S.Y.; Mok, H.K.; Lee, H.; Park, S.M.; Huh, J.S.; Ryu, J.; Park, J.H. Attitudes towards second opinion services in cancer care: A nationwide survey of oncologists in Korea. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2016, 46, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Logan, S.; Anazodo, A. The psychological importance of fertility preservation counseling and support for cancer patients. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 98, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A.; Ahlgren, J.; Smedby, K.E.; Gorman, J.R.; Hellman, K.; Henriksson, R.; Ståhl, O.; Wettergren, L.; Lampic, C. Prevalence and predictors for fertility-related distress among 1010 young adults 1.5 years following cancer diagnosis—Results from the population-based Fex-Can Cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2023, 62, 1599–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.H.; Strohl, H.B.; Su, H.I. Fertility preservation before and after cancer treatment in children, adolescents, and young adults. Cancer 2024, 130, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selter, J.; Huang, Y.; Becht, L.C.G.; Palmerola, K.L.; Williams, S.Z.; Forman, E.; Ananth, C.V.; Hur, C.; Neugut, A.I.; Hershman, D.L.; et al. Use of fertility preservation services in female reproductive-aged cancer patients. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 328.e1–328.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.; Shliakhtsitsava, K.; Natarajan, L.; Myers, E.; Dietz, A.C.; Gorman, J.R.; Martínez, M.E.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Su, H.I. Fertility counseling before cancer treatment and subsequent reproductive concerns among female adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer 2019, 125, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukaite-Ruibiene, E.; van der Perk, M.E.M.; Vaitkeviciene, G.E.; Bos, A.M.E.; Bumbuliene, Z.; Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.v.D.; Rascon, J. Evaluation of oncofertility care in childhood cancer patients: The EU-Horizon 2020 twinning project TREL initiative. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1212711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omesi, L.; Narayan, A.; Reinecke, J.; Schear, R.; Levine, J. Financial Assistance for Fertility Preservation Among Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients: A Utilization Review of the Sharing Hope/LIVESTRONG Fertility Financial Assistance Program. J. Adolesc. Young-Adult Oncol. 2019, 8, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, E.; Kato, M.; Wada, S.; Yoshida, S.; Shimizu, C.; Miyoshi, Y. Physicians’ practice of discussing fertility preservation with cancer patients and the associated attitudes and barriers. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, N.; van Delft, F.W.; Hale, J.P.; Stewart, J.A. Fertility Preservation Care for Children and Adolescents with Cancer: An Inquiry to Quantify Professionals’ Barriers. J. Adolesc. Young-Adult Oncol. 2017, 6, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotopoulou, N.; Ghuman, N.; Sandher, R.; Herbert, M.; Stewart, J. Barriers and facilitators towards fertility preservation care for cancer patients: A meta-synthesis. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tishelman, A.C.; Sutter, M.E.; Chen, D.; Sampson, A.; Nahata, L.; Kolbuck, V.D.; Quinn, G.P. Health care provider perceptions of fertility preservation barriers and challenges with transgender patients and families: Qualitative responses to an international survey. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Anazodo, A.; Logan, S. Systematic review of fertility preservation patient decision aids for cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.J. Optimizing the opportunity for female fertility preservation in a limited time-frame for patients with cancer using in vitro maturation and ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 111, 258–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamzatova, Z.; Komlichenko, E.; Kostareva, A.; Galagudza, M.; Ulrikh, E.; Zubareva, T.; Sheveleva, T.; Nezhentseva, E.; Kalinina, E. Autotransplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue—Effective method of fertility preservation in cancer patients. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2014, 30, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, R.; Hackl, J.; Lotz, L.; Hoffmann, I.; Beckmann, M.W. Pregnancies and live births after 20 transplantations of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in a single center. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoover, S.M.; Bratton, S.L.; Roach, E.R.; Olson, L.M. Parental experiences and recommendations in donation after circulatory determination of death. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 15, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sque, M.; Walker, W.; Long-Sutehall, T.; Morgan, M.; Randhawa, G.; Rodney, A. Bereaved donor families’ experiences of organ and tissue donation, and perceived influences on their decision making. J. Crit. Care 2018, 45, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luberda, K.; Cleaver, K. How modifiable factors influence parental decision-making about organ donation. Nurs. Child. Young-People 2017, 29, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achkar, T.; Wilson, J.; Simon, J.; Rosenzweig, M.; Puhalla, S. Metastatic breast cancer patients: Attitudes toward tissue donation for rapid autopsy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 155, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, N.N.; Klosky, J.L.; Meacham, L.; Quinn, G.P.; Kelvin, J.F.; Cherven, B.; Freyer, D.R.; Dvorak, C.C.; Brackett, J.; Ahmed-Winston, S.; et al. Fertility Preservation Practices at Pediatric Oncology Institutions in the United States: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, e550–e558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (N = 215) | |

|---|---|

| AGE | |

| N | 215 |

| Mean (SD) | 7.7 (5.2) |

| GENDER | |

| Male | 115 (53.5%) |

| Female | 100 (46.5%) |

| SITE | |

| Adrenal | 1 (0.5%) |

| Diaphragm | 2 (0.9%) |

| Genitourinary (bladder and/or prostate) | 33 (15.3%) |

| Genitourinary (not including above) | 41 (19.1%) |

| Head and Neck (Non-parameningeal) | 31 (14.4%) |

| Hepatobiliary | 4 (1.9%) |

| Limbs | 44 (20.5%) |

| Lungs | 1 (0.5%) |

| Nasopharynx | 1 (0.5%) |

| Orbit (eye and surrounding structures) | 20 (9.3%) |

| Parameningeal | 30 (14.0%) |

| Primary unknown | 2 (0.9%) |

| Spine | 3 (1.4%) |

| Trunk | 2 (0.9%) |

| HISTOLOGY | |

| Alveolar | 80 (38.3%) |

| Anaplastic | 1 (0.5%) |

| Botryoid | 5 (2.4%) |

| Embryonal | 114 (54.5%) |

| Pleomorphic | 2 (1.0%) |

| Spindle cell | 7 (3.3%) |

| Missing | 6 |

| POSITIVE LYMPH NODES AT DIAGNOSIS | |

| No | 140 (68.3%) |

| Yes | 65 (31.7%) |

| Missing | 10 |

| METASTASIS AT DIAGNOSIS | |

| No | 127 (60.5%) |

| Yes | 83 (39.5%) |

| Missing | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almohtasib, J.; Boswell, T.C.; Granberg, C.F.; Gargollo, P.C. Treatment Access and Caregiver Experience in Pediatric Rhabdomyosarcoma: Results of an Online Survey. Children 2025, 12, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040435

Almohtasib J, Boswell TC, Granberg CF, Gargollo PC. Treatment Access and Caregiver Experience in Pediatric Rhabdomyosarcoma: Results of an Online Survey. Children. 2025; 12(4):435. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040435

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmohtasib, Jamil, Timothy C. Boswell, Candace F. Granberg, and Patricio C. Gargollo. 2025. "Treatment Access and Caregiver Experience in Pediatric Rhabdomyosarcoma: Results of an Online Survey" Children 12, no. 4: 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040435

APA StyleAlmohtasib, J., Boswell, T. C., Granberg, C. F., & Gargollo, P. C. (2025). Treatment Access and Caregiver Experience in Pediatric Rhabdomyosarcoma: Results of an Online Survey. Children, 12(4), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12040435