Neonatal Mortality Due to Early-Onset Sepsis in Eastern Europe: A Review of Current Monitoring Protocols During Pregnancy and Maternal Demographics in Eastern Europe, with an Emphasis on Romania—Comparison with Data Extracted from a Secondary Center in Southern Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Data on Neonatal Mortality and Early-Onset Sepsis (EOS) in Eastern Europe

1.2. Trends in Neonatal Mortality over the Past Decade

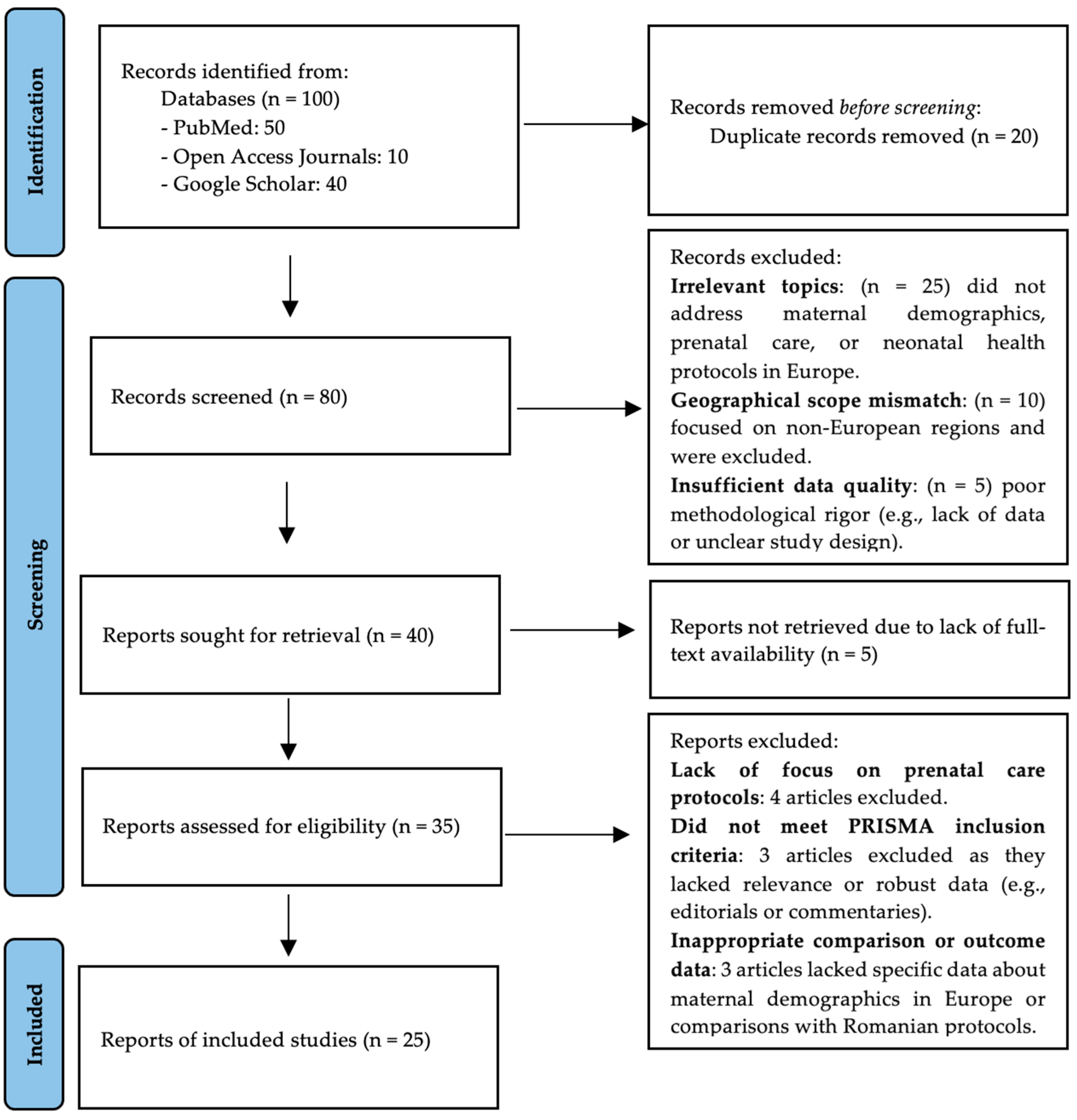

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Examined neonatal mortality, EOS, or maternal health in Eastern Europe.

- Addressed prenatal monitoring protocols or maternal demographics.

- Were peer-reviewed, published between January 2000 and August 2024, and written in English.

- Studies lacking full text.

- Non-research articles (e.g., opinion pieces, editorials).

- Papers focused on non-human subjects or regions outside Europe.

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Results

3. Review Findings

3.1. Current Monitoring Protocols During Pregnancy in Europe

3.1.1. Standardized Guidelines

3.1.2. Prenatal Monitoring

3.1.3. Romanian Prenatal Care Protocol

3.1.4. Advanced Diagnostics

3.2. Maternal Demographics in Eastern Europe and Their Impact

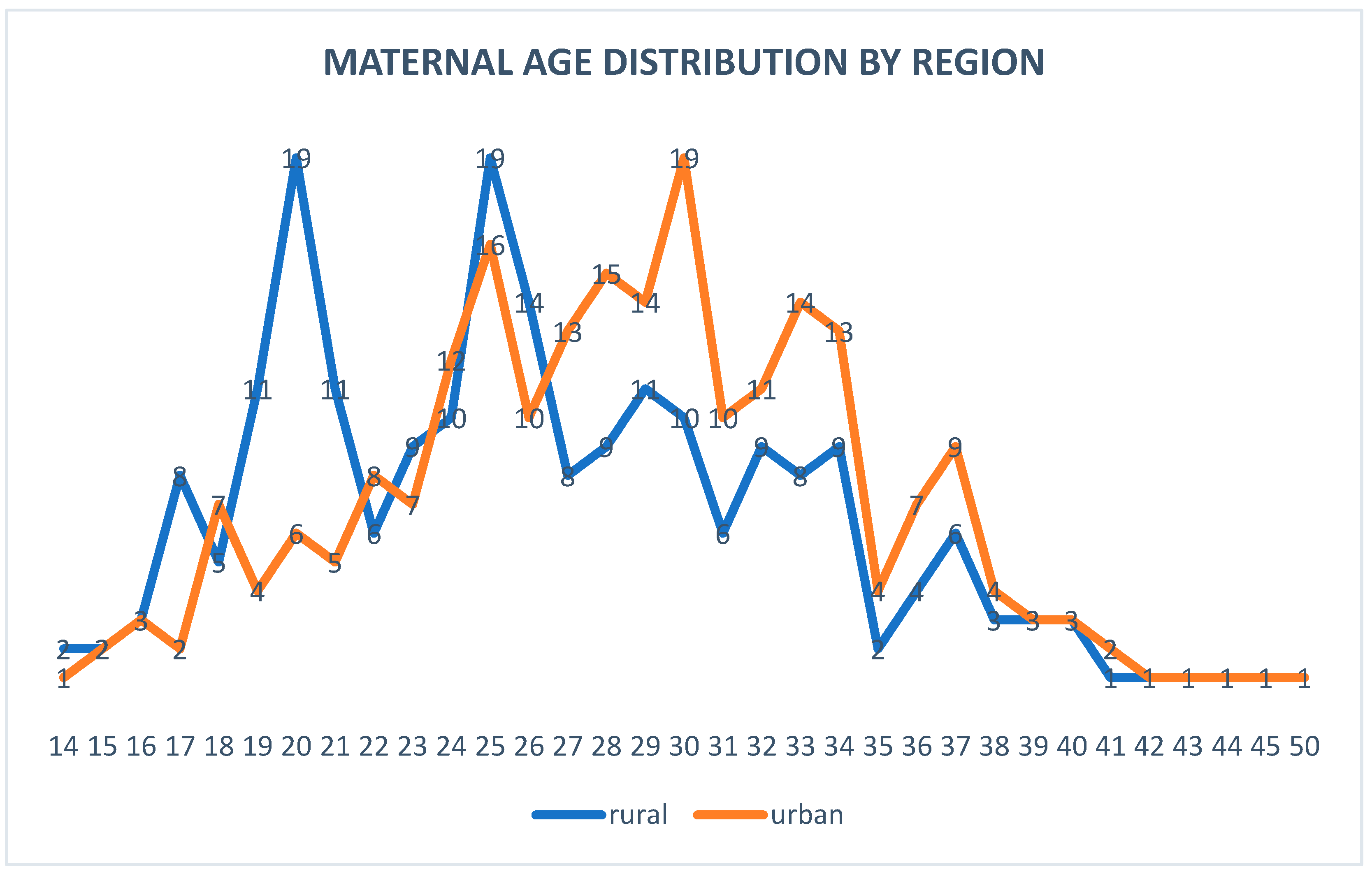

3.2.1. Maternal Age

- Eastern Europe Trends

- Romania-Specific Data

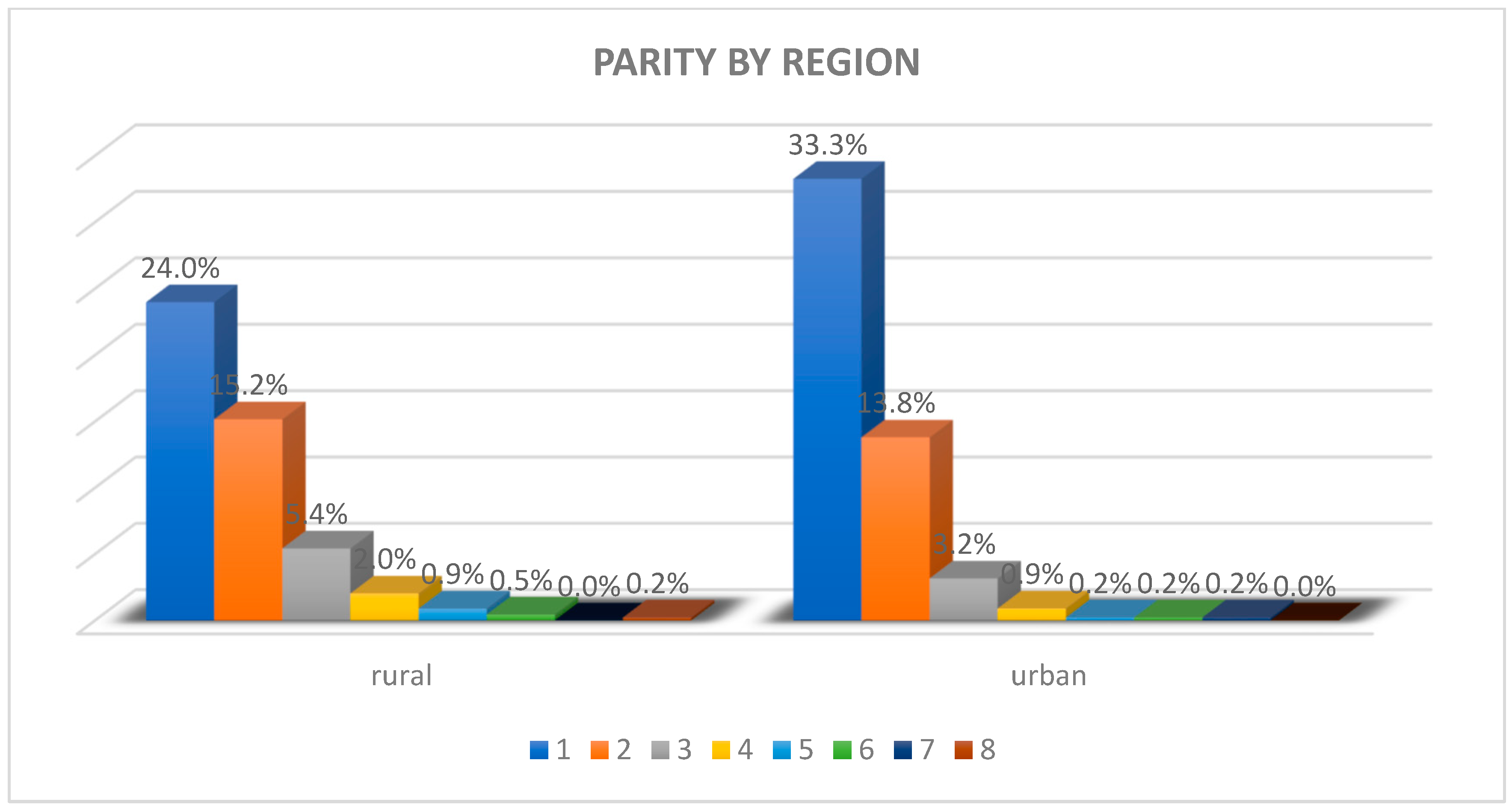

3.2.2. Parity

- Eastern Europe Trends

- Romania-Specific Data

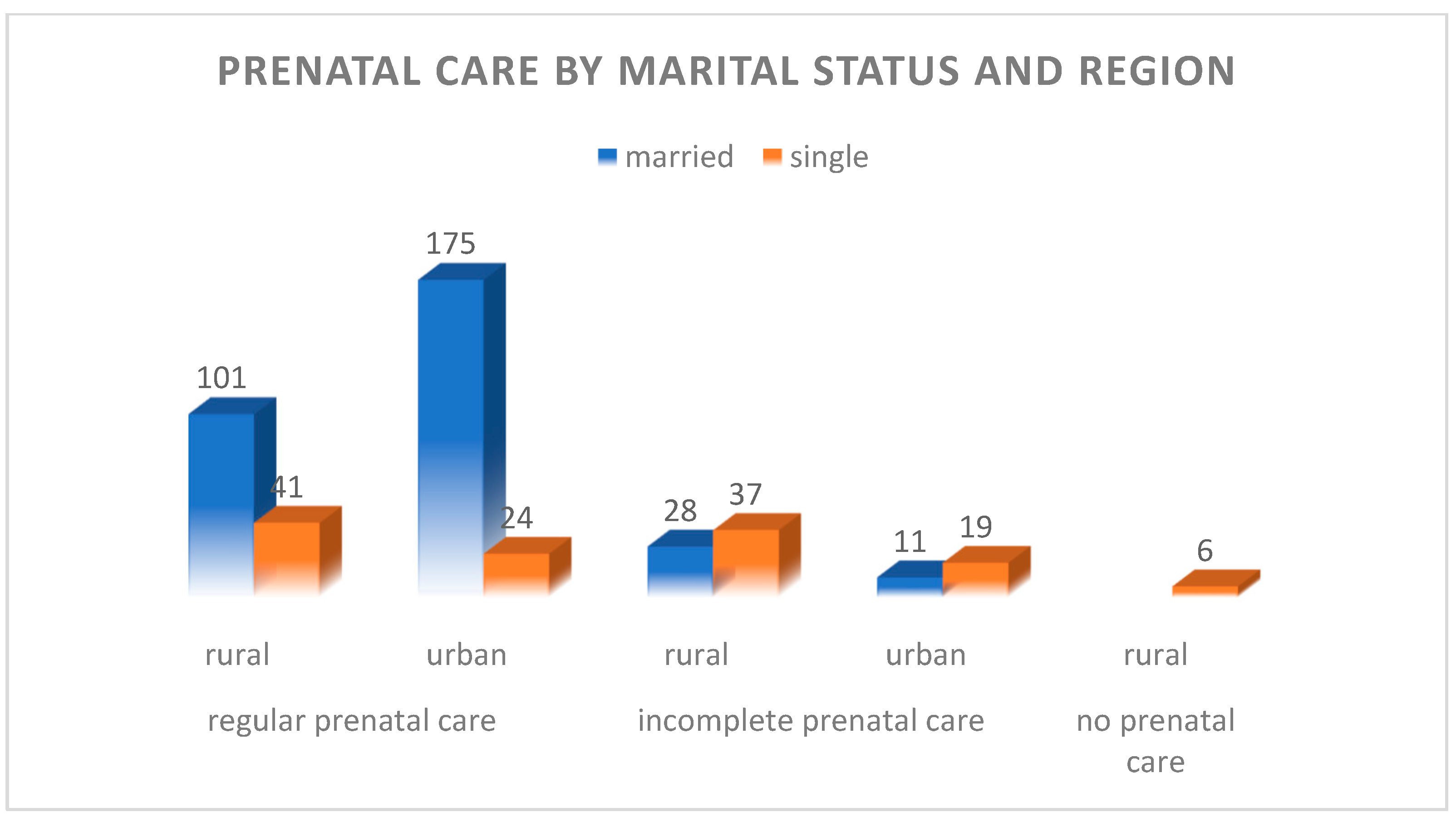

3.2.3. Marital Status

- Eastern Europe Trends

- Romania-Specific Data

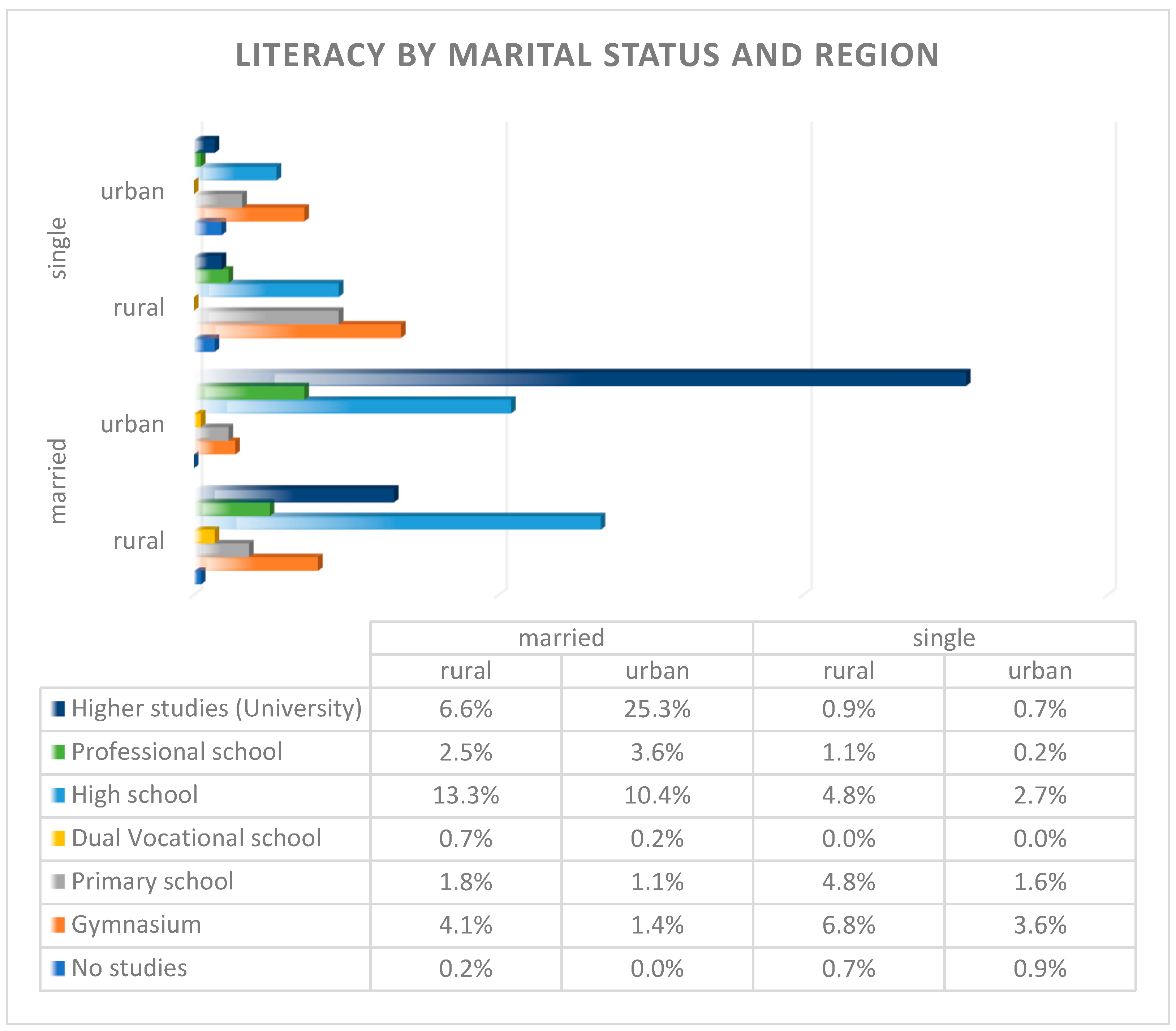

3.2.4. Literacy and Health Literacy

- Eastern Europe Trends

- Romania-Specific Data

3.3. Costs and Burdens Associated with Prenatal Care

3.3.1. Direct Costs

3.3.2. Summary of Indirect Costs

- -

- -

- -

- Long-term Healthcare Costs: Managing complications arising from pregnancy disorders can lead to ongoing healthcare expenses that burden families financially over time [12].

- -

- Economic Impact on Family Income: Reduced working hours while managing health issues can have significant effects on overall family income, contributing to financial strain [26].

- -

- Maternal Healthcare Disparities: Economic implications arise from disparities in maternal healthcare, where under-resourced communities may face higher indirect costs due to inadequate access to care [27].

- -

- Long-term Effects of Maternal Morbidity: Health issues can have lasting economic effects on families, affecting their financial stability and overall quality of life [26].

- -

- Reduced Outreach Capacity: Funding limitations can hinder maternal outreach efforts, reducing the availability of educational and healthcare resources for expectant mothers [16].

- -

- Impact on Labor Force Participation: The pandemic has exacerbated issues related to labor force participation for those needing care, as many individuals had to prioritize health over work [19].

- -

- High Complication Rates in Underserved Communities: Economic impacts are more pronounced in underserved communities, where high rates of complications can lead to increased healthcare costs and loss of income [14].

- -

- Long-term Implications for Children: Maternal health issues can have long-term implications for children’s futures, including potential impacts on their health and economic opportunities [28].

- -

- Time Lost Navigating Care Pathways: The time spent by mothers navigating culturally relevant care pathways detracts from their ability to engage in work or other productive activities [21].

3.3.3. Summary of Hidden Costs

- -

- Transportation and Time Off Work: Additional expenses arise from traveling to healthcare facilities, coupled with the need for time off work for medical appointments, impacting financial stability [15].

- -

- Childcare Costs: Families incur costs for childcare for siblings while attending prenatal appointments, adding to the overall financial burden [22]

- -

- Missed Work Opportunities: Attending multiple healthcare appointments can lead to missed work opportunities, resulting in lost income and reduced productivity [36].

- -

- Emotional and Psychological Burdens: Navigating the healthcare system creates significant emotional and psychological stress for expectant mothers, complicating their overall health experience [26].

- -

- Reduced Mental Health Support: Emotional distress can limit access to mental health resources vital for coping with the challenges of pregnancy and motherhood [12].

- -

- Inadequate Follow-Up Care: Costs associated with insufficient follow-up care can lead to complications and additional healthcare needs, straining family resources [17].

- -

- Emergency Obstetric Care Variability: The unpredictability of costs related to emergency obstetric care can create financial uncertainty for families [35].

- -

- Unfunded Education Costs: Educational programs on prenatal care may lack funding, leading to missed opportunities for women to gain crucial knowledge about their health [26].

- -

- Policy Implementation Challenges: Burdens arise when policies are implemented without adequate resources, affecting the quality and accessibility of maternal healthcare services [14].

- -

- Pandemic-Related Psychological Toll: Fear stemming from the pandemic can deter individuals from seeking necessary healthcare, impacting maternal and child health outcomes [19].

- -

- Transportation Resource Allocation: Time and resources spent on seeking transportation to care centers can detract from other essential activities, such as work or family care [21].

- -

- Societal Costs for Marginalized Groups: Poorer health outcomes for marginalized groups lead to societal costs, as these populations may require more extensive healthcare services and support [27].

- -

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Data Found in Our Study

4.1.1. Maternal Age

4.1.2. Parity

4.1.3. Literacy

4.1.4. Marital Status

4.2. Challenges in Prenatal Care in Romania

4.2.1. Rural–Urban Divide

4.2.2. Cultural Barriers

4.2.3. Policy and Infrastructure Gaps

4.3. Recommendations for Improving Prenatal Care in Romania

4.3.1. Enhance Access to Healthcare Services

4.3.2. Improve Transportation and Support Services

4.3.3. Increase Education and Awareness Campaigns

4.3.4. Integrate Culturally Competent Care

4.3.5. Strengthen Mental Health Services

4.3.6. Improve Policy and Funding Allocation

4.3.7. Foster Partnerships and Community Involvement

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF. Romania Country Data Profile; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; UNICEF. Neonatal Mortality and Infections: Global Burden and Strategies for Reduction; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT. Neonatal Mortality Statistics—2023 Update; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis: Global Challenges and Interventions; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Roma Children in Romania: A Study on Poverty and Health; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Romania. Universal Language of Motherhood: Refugees and Maternal Care in Romania; UNICEF Romania: București, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- De Hert, S.; Breban, I.; Radu, G.; Vasile, A.; Tapalaga, I. Healthcare Disparities in Urban and Rural Romania: Challenges in Access and Quality. Int. J. Health Serv. 2022, 52, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Addressing the Burden of Early-Onset Sepsis in Rural Populations; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alemán Riganti, A.V. Quality of Maternal and Perinatal Care: Strategies for Its Monitoring and Improvement in Latin America; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aniekwu, N.I.; Uzodike, E.N. Reproductive Health Law and Policy: Legal Reforms in the African Sub-Region. Hemisph. Stud. Cult. Soc. 2008, 23, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Panaitescu, A.M.; Ciobanu, A.M.; Popescu, M.R.; Huluta, I.; Botezatu, R.; Peltecu, G.; Gica, N. Incidence of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy in Romania. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2020, 39, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobzeanu, M.L. Neonatal Outcomes in Rural Romania: Challenges and Solutions. Rom. Pediatr. Soc. J. 2022, 17, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stativă, E.; Rus, A.V.; Colman, L.C. Characteristics and Prenatal Care Utilisation of Romanian Pregnant Women. Eur. J. Contracept Reprod. Health Care 2014, 19, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanturidze, T. Technical Assistance for Project Management Unit APL 2, Within the Ministry of Health of Romania, in Order to Develop a Strategy for Primary Health Care in Underserved Areas and the Related Action Plan; FNPMF Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miteniece, E.; Gheorghita-Puscaselu, R.; Panaitescu, A.M.; Ciulpan, A. Maternal Care Inequities and Neonatal Health: A Focus on Eastern Europe. Eur. Public Health J. 2021, 31, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Maternal Health and Neonatal Outcomes in Rural Populations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Panaitescu, A.M. Risk Factors for Neonatal Sepsis: A Study in Rural Romania. Ginecol. Și Perinatol. Pract. 2020, 20, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Horga, M. Strategic Assessment of Maternal Care Policies in Romania; WHO Report: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cionca, O.; Gheorghita, R.; Cobzeanu, M.L. Prenatal Care Challenges for Vulnerable Populations. SOGR Public 2015, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, A.; Spada, C.; Reggiani, M.L.B.; Guidotti, I.; Baroni, L.; Bacchi Reggiani, M.L.; Ferrari, F.; Dodi, I.; Perrone, E.; Lucaccioni, L. Epidemiology and Prevention of Neonatal Sepsis and Meningitis in Europe. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A. Cost Barriers to Prenatal Care in Eastern Europe. Health Econ. 2019, 28, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sántha, Á. The Sociodemographic Determinants of Health Literacy in the Ethnic Hungarian Mothers of Young Children in Eastern Europe. Int J Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miteniece, E. Access to Adequate Maternal Care in Eastern Europe. Ph.D. Thesis, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT. Maternal Healthcare Statistics in Europe; EUROSTAT: Luxembourg, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Advancements in Prenatal Diagnostics and Their Accessibility in Europe; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Filip, R.; Cobzeanu, M.L.; Drandic, D.; Haba, R.M. Public Health Challenges in Maternal Care during COVID-19. J. Med. 2022, 12, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, J.; Sutherland, L.; Lafferty, D. Ethnic Variations in Labor Outcomes in Europe. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 118, 1313–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, C.A. Reproduction and Cultural Health Care Dynamics in Romania. In Medical Anthropology; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2022; ISBN 978829604, 9781978829602. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. European Action Plan for Strengthening Public Health Capacities and Services; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, A. GBS Screening and IAP: European Guidelines. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Schrag, S.J.; Verani, J.R.; McGee, L.; Reingold, A.; Petit, S.; Beall, B. Epidemiology of Group B Streptococcus in Europe. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 1008–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Weltgesundheitsorganisation (Ed.) Abortion and Contraception in Romania: A Strategic Assessment of Policy, Programme and Research Issues, Report of a Strategic Assessment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; ISBN 978-973-99531-6-0. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Romania. Better Healthcare for Every Mother and Child; UNICEF Romania: București, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ciulpan, L.; Popescu, C.; Georgescu, M.; Ionescu, S. Barriers to Group B Streptococcus Screening in Romanian Women: Challenges and Implications. Rom. J. Med. 2024, 45, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Essential Screening Tests in Maternal and Neonatal Health: Gaps and Recommendations; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT. Maternal Age and Its Impact on Pregnancy Outcomes in Eastern Europe; Eurostat: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT. Average Maternal Age at Childbirth in Romania and Western Europe; Eurostat: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hincu, M.A.; Gheorghita-Puscaselu, R.; Filip, R.; Cobzeanu, M.L.; Ciulpan, A.; Drandic, D.; Panaitescu, A.M.; Berardi, A.; Melin, P.; Toma, M. Neonatal Sepsis in Eastern Europe: Current Trends and Challenges. Pediatr. Rom. 2024, 23, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health Overview: Focus on Pregnancy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Romania. Adolescent Pregnancy in Romania: Current Trends and Implications; UNICEF Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Adolescent Motherhood in Romania: Statistics and Outcomes; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barcaite, E. Socioeconomic Barriers and Neonatal Outcomes: An Observational Study. Int. J. Pediatr. 2008, 38, 345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Chanturidze, T. Maternal and Neonatal Health in the Transition Economies of Eastern Europe. Healthc. Policy J. 2021, 15, 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Barcaite, E.; Bartusevicius, A.; Tameliene, R.; Kliucinskas, M.; Maleckiene, L.; Nadisauskiene, R. Prevalence of Maternal Group B Streptococcal Colonisation in European Countries. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2008, 87, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.M.; Casanova, C.; Caldas, J. Migrant Women’s Perceptions of Healthcare During Pregnancy and Early Motherhood: Addressing the Social Determinants of Health. Immigrant Minority Health 2014, 16, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacu, A. Roma Migration and Maternal Health Care Access. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2011, 37, 647–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, N.; Ansari Jaberi, A.; Ansari Jaberi, K.; Negahban Bonabi, T. The Role of Maternal Health Literacy in Breastfeeding Pattern. J. Nurs. Midwifery Sci. 2018, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, L.C.; Kagan, K.; Etches, D. FIGO International Prenatal Care Initiatives. FIGO Rep. 2019, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Antenatal Care Recommendations: Improving Outcomes through Monitoring and Management; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bojovic, N.; Krstic, F.; Radojković, M. COVID-19’s Impact on Maternal Health Policies in Europe. Health Policy 2021, 125, 586–596. [Google Scholar]

- PHIRI—Population Health Information Research Infrastructure. Perinatal Health. Case Study Report. Euro-Peristat Network—European Union. 2022. Available online: https://www.phiri.eu/sites/default/files/2023-12/PHIRI_UCC_%20with%20Appendix.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Filip, R.; Savin, R.; Olaru, O.G. Predicting Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorders in a Cohort of Pregnant Patients in the North-East Region of Romania—Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasound and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Diagnostics 2020, 12, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROSTAT. Fertility Rates and Maternal Health in Europe; European Commission Report: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Delvaux, T.; Buekens, P.; Godin, I.; Boutsen, M. Barriers to Prenatal Care in Europe. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 21, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, G.; Giurcanu, M.; Diczfalusy, E. Advances in Fetal Medicine and Maternal Care in Eastern Europe. Diczfalusy Found. Rep. 2020, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, M. Medical Abortion and Maternal Care in Moldova. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 157, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Maternal Mortality: A Global Challenge; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gudjónsdóttir, M.J.; Elfvin, A.; Hentz, E.; Adlerberth, I.; Tessin, I.; Trollfors, B. Changes in Incidence and Etiology of Early-Onset Neonatal Infections 1997–2017—A Retrospective Cohort Study in Western Sweden. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, A. Risk Factors for Early-Onset Sepsis in Neonates: Insights from Romania. PMC 2022, 9, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Johri, A.K.; Lata, H.; Yadav, P.; Dua, M.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X.; Homma, A.; Barocchi, M.A.; Bottomley, M.J.; Saul, A.; et al. Epidemiology of Group B Streptococcus in Developing Countries. Vaccine 2013, 31, D43–D45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Prenatal Health Challenges in Eastern Europe; WHO Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyes, S.-G.; Chiriac, V.D.; Gluhovschi, A.; Mihaela, V.; Dahma, G.; Mocanu, A.G.; Neamtu, R.; Silaghi, C.; Radu, D.; Bernad, E.; et al. The Influence of Maternal Factors on Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Admission and In-Hospital Mortality in Premature Newborns from Western Romania: A Population-Based Study. Medicina 2022, 58, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Country | Maternal Age | Parity | Literacy | Marital Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panaitescu, A.M. et al. (2020) [11] | Romania | The study discusses the higher prevalence of hypertensive disorders in women aged ≥ 35, reflecting trends of advanced maternal age | Highlights increased risk for hypertensive disorders in nulliparous women compared to multiparous ones | Not discussed | Not discussed |

| Cobzeanu, M.L. et al. (2022) [12] | North-East Romania | Increased prevalence of accreta spectrum disorders in women above 30 years | Higher incidence in grand multiparous women, often associated with a history of cesarean delivery | The paper alludes to low health literacy rates contributing to delayed presentations and diagnosis of complications | Not discussed |

| Stativa, E. et al. (2014) [13] | Romania | Younger mothers were found to underutilize prenatal care services more than older mothers. Teenage pregnancies contributed to increased risk of complications. | Higher parity correlated with decreased use of prenatal care, particularly in rural and socioeconomically disadvantaged areas. First-time mothers were more likely to seek prenatal care. | Health literacy was closely tied to socioeconomic status and geographic location; women with lower literacy or educational attainment had higher rates of underutilization. | Unmarried women or single mothers were less likely to access adequate prenatal care. Cultural and social stigmas, along with economic hardships, create additional barriers for unmarried women. |

| Chanturidze, T. (2012) [14] | Romania | Trends of increasing maternal age, with a notable number of pregnancies occurring among women aged 30 and above, reflecting a shift towards delayed childbirth in urban areas | Women in rural areas show higher parity rates compared to urban populations due to limited access to contraception | Highlights disparities in health literacy; lower education levels are prevalent among rural populations, hindering understanding of maternal health | Observes a significant proportion of births occurring among unmarried women, particularly in younger women and marginalized groups. |

| Miteniece, E. (2021) [15] | Eastern Europe | Notes trends of adolescent pregnancies in rural Eastern Europe and delayed pregnancies beyond 30 years in urban areas | Higher parity in rural regions due to low contraceptive use | Low educational attainment linked to reduced prenatal care adherence, particularly in rural communities | High rates of pregnancies among unmarried women in marginalized ethnic groups and conservative communities |

| WHO (2004) [16] | Romania | Adolescent pregnancies remain common in rural areas due to limited access to education and contraception | Observes unintended pregnancies contributing to higher parity in underserved communities | Not discussed | Discusses the stigma surrounding unmarried pregnant women and its impact on healthcare access |

| Panaitescu, A.M. (2020) [17] | Romania | Adolescent pregnancies cited as a key issue in disadvantaged areas | Notes a higher birth rate among women with limited education | Links low literacy to disparities in access to prenatal care, particularly in rural Romania | Not available |

| Horga, M. (2004) [18] | Romania | Adolescents represent a significant percentage of mothers in rural areas | Low contraception use leads to higher parity in underserved populations | Not discussed | High proportion of pregnancies among unmarried women in disadvantaged communities |

| Cionca, O. et al. (2015) [19] | Romania | Emphasizes the high prevalence of teenage pregnancies in marginalized groups | Not discussed | Vulnerable populations, such as Roma women, show lower literacy levels, reducing engagement in prenatal care | Limited social support for unmarried women affects care access |

| Berardi, A. et al. (2017) [20] | Various European countries | The study identifies an increasing trend of pregnancies among older women (≥35 years) which is more pronounced in Western and Central Europe compared to Eastern Europe | Discusses variations in parity, noting that certain Eastern European countries have higher rates of multiparity compared to Western counterparts due to cultural norms and family planning policies | Mentions that mothers with higher literacy levels tend to utilize antenatal services more effectively and adhere to recommended healthcare guidelines | The article notes that marital status significantly impacts access to care; unmarried mothers in Eastern Europe often encounter stigmas that affect their healthcare utilization |

| Almeida, A.C. et al. (2019) [21] | Europe | The findings indicate a demographic shift with increasing maternal age at first childbirth across several Eastern European countries, mirroring trends observed in Romania | Reports a trend of high-parity pregnancies in Eastern European countries due to less access to effective family planning methods | The study emphasizes that lower levels of maternal education correlate with poorer outcomes in maternity care practices, particularly in Eastern Europe | Highlights that increased rate of births outside marriage, especially in Eastern Europe, influence maternal care-seeking behaviors and health outcomes |

| Sántha, Á. (2021) [22] | Romania, Hungary, Slovakia (focus on ethnic Hungarian mothers) | Younger mothers often struggle with understanding health information, resulting in less effective prenatal and postnatal care utilization | Women with higher parity had lower health literacy levels | Low levels of health literacy associated with lower educational attainment | Married women were more likely to have better health literacy and access to prenatal care |

| Study | Direct Costs | Indirect Costs | Hidden Costs | Burdens |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panaitescu, A.M. et al. (2020) [11] | Hospitalization costs due to hypertensive disorders, routine prenatal visits, and prescribed medications | Lost income for women unable to work due to complications | Additional expenses for transportation to healthcare facilities and time off work for appointments | Increased healthcare utilization leading to financial strain on families and the public health system |

| Miteniece, E. (2021) [23] | Out-of-pocket expenses for prenatal care services and consultations | Travel expenses for reaching healthcare centers, particularly in rural areas | Cost of childcare for siblings while attending prenatal appointments | Accessibility issues due to geographic location, leading to delayed or inadequate care during pregnancy |

| Stativa, E. et al. (2014) [13] | Lack of insurance and limited healthcare coverage; costs of medical consultations, laboratory tests and medications are significant for low-income families | Loss of income due to time off work and transportation costs for prenatal appointments for those living far from healthcare facilities | Informal payments to healthcare providers | Emotional and psychological stress due to limited access to care and financial costs. |

| Almeida, A.C. et al. (2019) [21] | Differences in healthcare expenditures for prenatal care across countries | Variation in lost productivity based on care accessibility | Emotional and psychological burdens of navigating the healthcare system | Disparities in care quality and access across different socioeconomic backgrounds |

| Cobzeanu, M.L. et al. (2022) [12] | Surgical costs associated with treating accreta spectrum disorders | Long-term healthcare costs for managing complications arising from these disorders | Emotional distress leading to reduced mental health support accessibility | Increased complexity in prenatal monitoring and treatment requiring specialized healthcare |

| Chanturidze, T. (2012) [14] | Funding for maternal health project initiatives and program management | Economic impact on family income due to reduced working hours while managing health issues | Costs associated with inadequate follow-up care | Systemic issues within healthcare infrastructure affecting maternal outcomes |

| Eurostat. (2023) [24] | Reported costs of maternal healthcare services across Europe, including Romania | Economic implications associated with maternal healthcare disparities | Variability in costs related to emergency obstetric care | Reflection of unequal access to care and resources across different regions |

| World Health Organization. (2022) [25] | Implementation costs for following WHO antenatal care guidelines | Long-term economic effects of maternal morbidity on families | Costs related to education on prenatal care that potentially go unfunded | Global disparities in adherence to recommended practices impacting maternal health |

| Horga, M. (2004) [18] | Resources dedicated to maternal care policies and programs | Reduced capacity for maternal outreach due to funding limitations | Burdens related to policy implementation without adequate resources | Inequities in maternal care access due to governmental resource allocation |

| Filip, R. et al. (2022) [26] | Increased expenses related to disruptions in care due to COVID-19 | Impact on labor force participation for those needing care during the pandemic | Psychological toll from pandemic-related fear affecting health-seeking behavior | The strain on healthcare systems leading to postponement of necessary prenatal care |

| Cionca, O. et al. (2015) [19] | Costs associated with providing care to vulnerable populations | Economic impact from high rates of complications in underserved communities | Time and resources spent seeking transportation to care centers | Vulnerability affecting access to timely care, leading to poorer maternal health outcomes |

| Walsh, J. et al. (2011) [27] | Documentation of varying healthcare costs based on ethnic backgrounds | Long-term implications of maternal health issues on children’s futures | Societal costs associated with poorer outcomes for marginalized groups | Disparities in outcomes due to ethnic variations in healthcare access and quality |

| Pop, C.A. (2022) [28] | Expenses related to cultural sensitivity training for healthcare providers | Time lost for mothers navigating culturally relevant care pathways | Impact of cultural norms on healthcare decisions | Cultural and systemic barriers creating additional stress for expectant mothers |

| Sántha, Á. (2021) [22] | Paying for health services (consultations, medications, diagnostic tests); lack of resources for minority populations | Transportation expenses for those living in rural areas; time off work affecting household income, especially for single mothers | Language barriers that required hiring interpreters; informal payments to healthcare providers | Navigating socioeconomic challenges and ethnic discrimination. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vulcănescu, A.; Siminel, M.-A.; Dinescu, S.-N.; Dijmărescu, A.-L.; Manolea, M.-M.; Săndulescu, S.-M. Neonatal Mortality Due to Early-Onset Sepsis in Eastern Europe: A Review of Current Monitoring Protocols During Pregnancy and Maternal Demographics in Eastern Europe, with an Emphasis on Romania—Comparison with Data Extracted from a Secondary Center in Southern Romania. Children 2025, 12, 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030354

Vulcănescu A, Siminel M-A, Dinescu S-N, Dijmărescu A-L, Manolea M-M, Săndulescu S-M. Neonatal Mortality Due to Early-Onset Sepsis in Eastern Europe: A Review of Current Monitoring Protocols During Pregnancy and Maternal Demographics in Eastern Europe, with an Emphasis on Romania—Comparison with Data Extracted from a Secondary Center in Southern Romania. Children. 2025; 12(3):354. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030354

Chicago/Turabian StyleVulcănescu, Anca, Mirela-Anișoara Siminel, Sorin-Nicolae Dinescu, Anda-Lorena Dijmărescu, Maria-Magdalena Manolea, and Sidonia-Maria Săndulescu. 2025. "Neonatal Mortality Due to Early-Onset Sepsis in Eastern Europe: A Review of Current Monitoring Protocols During Pregnancy and Maternal Demographics in Eastern Europe, with an Emphasis on Romania—Comparison with Data Extracted from a Secondary Center in Southern Romania" Children 12, no. 3: 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030354

APA StyleVulcănescu, A., Siminel, M.-A., Dinescu, S.-N., Dijmărescu, A.-L., Manolea, M.-M., & Săndulescu, S.-M. (2025). Neonatal Mortality Due to Early-Onset Sepsis in Eastern Europe: A Review of Current Monitoring Protocols During Pregnancy and Maternal Demographics in Eastern Europe, with an Emphasis on Romania—Comparison with Data Extracted from a Secondary Center in Southern Romania. Children, 12(3), 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030354