Oro-Functional Conditions in a 6-to-14-Year-Old School Children Population in Rome: An Epidemiological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Clinical Examination

- -

- A questionnaire, distributed in advance to the parents and/or guardians of the children involved, with open-ended questions regarding remote history and current oral and habitual behaviors (Figure 1);

- -

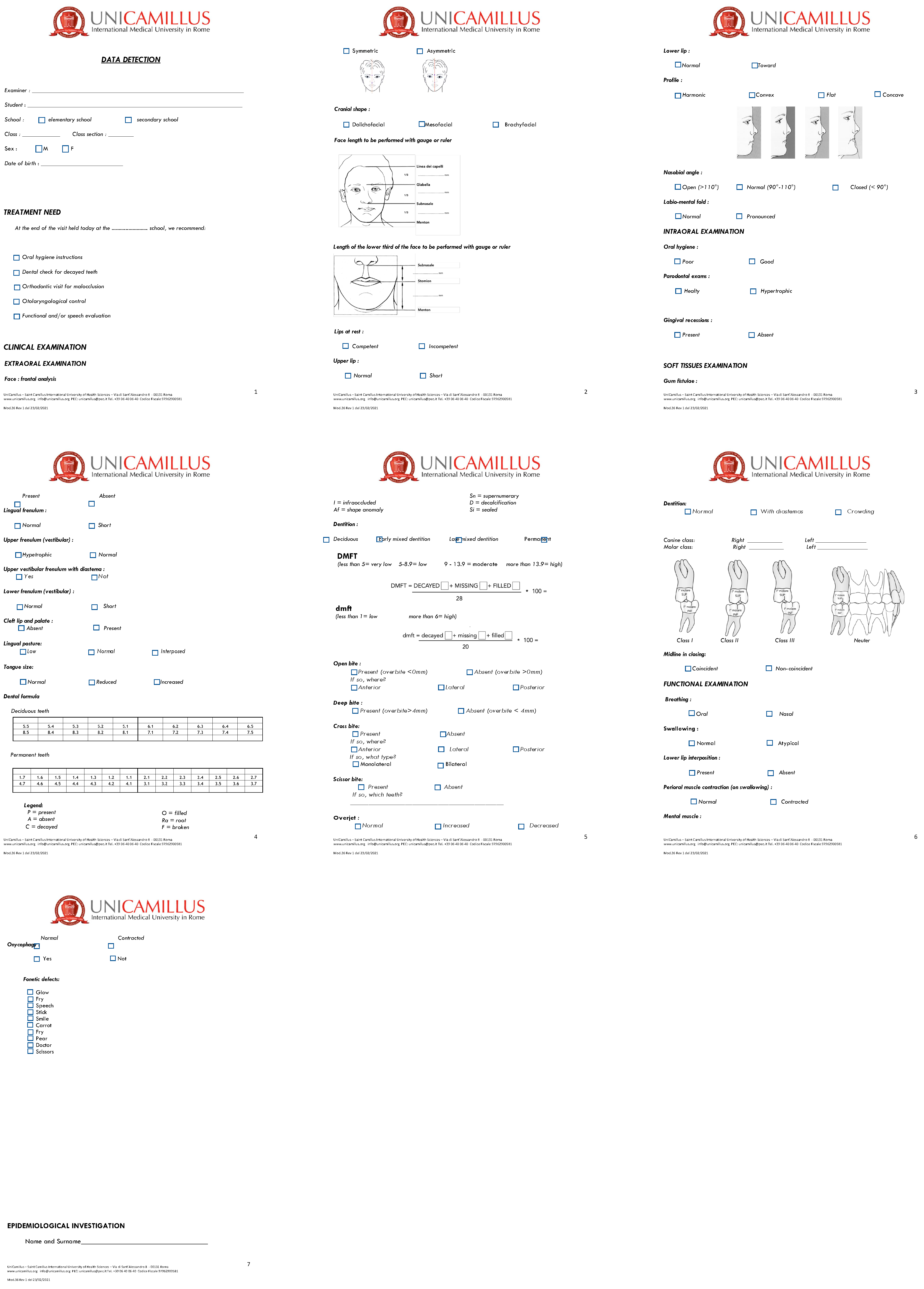

- A medical record filled out by the practitioners in charge of disease detection during the visit, consisting of forty closed-ended items and divided into five parts (extra-oral clinical examination, intraoral clinical examination, soft tissue analysis, dental formula, functional clinical examination of swallowing, breathing, and phonetics) (Figure 2).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Artnik, B. Health Promotion and Disease Prevention: A Handbook for Teachers, Researchers, Health Professionals and Decision Makers; Hans Jacobs Publishing Company: Lage, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett, E.; Haber, J.; Krainovich-Miller, B.; Bella, A.; Vasilyeva, A.; Lange Kessler, J. Oral Health in Pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal. Nurs. 2016, 4, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Malley, L.; Macey, R.; Allen, T.; Brocklehurst, P.; Thomson, F.; Rigby, J.; Lalloo, R.; Tomblin Murphy, G.; Birch, S.; Tickle, M. Workforce Planning Models for Oral Health Care: A Scoping Review. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2022, 1, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraihat, N.; Madae’en, S.; Bencze, Z.; Herczeg, A.; Varga, O. Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Oral-Health Promotion in Dental Caries Prevention among Children: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laganà, G.; Abazi, Y.; Beshiri Nastasi, E.; Vinjolli, F.; Fabi, F.; Divizia, M.; Cozza, P. Oral health conditions in an Albanian adolescent population: An epidemiological study. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laganà, G.; Masucci, C.; Fabi, F.; Bollero, P.; Cozza, P. Prevalence of malocclusions, oral habits and orthodontic treatment need in a 7- to 15-year-old schoolchildren population in Tirana. Prog. Orthod. 2013, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S.; Ferrazzano, G.F.; Beretta, M.; Paglia, L. Dental Caries Prevention: A Review on the Use of Dental Sealants. Available online: http://www.dentalmedjournal.it/files/2018/12/JDM_2018_004_INT@081-086.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2019).

- Perillo, L.; Masucci, C.; Ferro, F.; Apicella, D.; Baccetti, T. Prevalence of orthodontic treatment need in southern Italian schoolchildren. Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 32, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grippaudo, C.; Paolantonio, E.G.; Antonini, G.; Saulle, R.; La Torre, G.; Deli, R. Association between oral habits, mouth breathing and malocclusion. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2016, 36, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotta, S.; Bucci, R.; Simeon, V.; Martina, S.; Michelotti, A.; Valletta, R. Prevalence of malocclusion, oral parafunctions and temporomandibular disorder-pain in Italian schoolchildren: An epidemiological study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2019, 46, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campus, G.; Solinas, G.; Cagetti, M.G.; Senna, A.; Minelli, L.; Majori, S.; Montagna, M.T.; Reali, D.; Castiglia, P.; Strohmenger, L. National Pathfinder survey of 12-year-old Children’s Oral Health in Italy. Caries Res. 2007, 41, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, L.J.; Healey, D.L. Prevention and caries risk management in teenage and orthodontic patients. Aust. Dent. J. 2019, 64 (Suppl. S1), S37–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozza, I.; Capasso, F.; Calcagnile, F.; Anelli, A.; Corridore, D.; Ferrara, C.; Ottolenghi, L. School-age dental screening: Oral health and eating habits. Clin. Ter. 2019, 170, e36–e40. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, C.H.; Bagramian, R.A.; Hashim Nainar, S.M.; Straffon, L.H.; Shen, L.; Hsu, C.Y.S. High caries prevalence and risk factors among young preschool children in an urban community with water fluoridation. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2014, 24, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellante De Martiis, G.; Borgioli, A.; Gavasci, R.; Simonetti D’Arca, A. Considerazioni sulla fattibilità della fluorazione dell’acqua potabile nell’area metropolitana romana [The feasibility of fluoridation of the drinking water in the Rome metropolitan area]. Ann. Ig. 1994, 6, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maldupa, I.; Sopule, A.; Uribe, S.E.; Brinkmane, A.; Senakola, E. Caries Prevalence and Severity for 12-Year-Old Children in Latvia. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 3, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, P.E. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century—The approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Commun. Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2003, 31, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, R.A. Why Parents Should Never Consider Baby Teeth as Practice Teeth. 2010. Available online: https://www.friscosdentists.com/about-us/blog/2010/june/why-parents-should-never-consider-baby-teeth-as-/ (accessed on 9 August 2012).

- Lynch, R.J. The primary and mixed dentition, post-eruptive enamel maturation and dental caries: A review. Int. Dent. J. 2013, 63 (Suppl. 2), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buczkowska-Radlinska, J.; Szyszka-Sommerfeld, L.; Wozniak, K. Anterior tooth crowding and prevalence of dental caries in children in Szczecin, Poland. Community Dent. Health 2012, 2, 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gábris, K.; Márton, S.; Madléna, M. Prevalence of malocclusions in Hungarian adolescents. Eur. J. Orthod. 2006, 5, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, F.; Grabowski, R. Malocclusion and caries prevalence: Is there a connection in the primary and mixed dentitions? Clin. Oral Investig. 2004, 2, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazeminia, M.; Abdi, A.; Shohaimi, S.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Salari, N.; Mohammadi, M. Dental caries in primary and permanent teeth in children’s worldwide, 1995 to 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Face Med. 2020, 1, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, M.; D’Antonio, F.; Reierth, E.; Basnet, P.; Trovik, T.A.; Orsini, G.; Manzoli, L.; Acharya, G. Dental caries and preterm birth: A systematic review and metaanalysis. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, P.; Petersen, P.E. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of dental diseases. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Locker, D.; Berall, G.; Pencharz, P.; Kenny, D.J.; Judd, P. Malnourishment in a population of young children with severe early childhood caries. Pediatr. Dent. 2006, 28, 254–259. [Google Scholar]

- Peressini, S. Pacifier use and early childhood caries: An evidence-based study of the literature. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2003, 1, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Zhao, T.; Qin, D.; Hua, F.; He, H. The impact of mouth breathing on dentofacial development: A concise review. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 929165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, G.; Vena, F.; Negri, P.; Pagano, S.; Barilotti, C.; Paglia, L.; Colombo, S.; Orso, M.; Cianetti, S. Worldwide prevalence of malocclusion in the different stages of dentition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 2, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Cenzato, N.; Nobili, A.; Maspero, C. Prevalence of Dental Malocclusions in Different Geographical Areas: Scoping Review. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, R.R.; Nayme, J.G.; Garbin, A.J.; Saliba, N.; Garbin, C.A.; Moimaz, S.A. Prevalence of malocclusion and related oral habits in 5-to 6-year-old children. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2012, 10, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Age (Year) | Total Sample | Composition Sample by Age | Composition Sample by Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M n | F n | M + F n | M + F % | Males % | Females % | |

| School year 2021–2022 | ||||||

| 6 | 20 | 18 | 38 | 16.9 | 52.6 | 47.4 |

| 7 | 20 | 12 | 32 | 13.7 | 62.5 | 37.5 |

| 8 | 23 | 27 | 50 | 22.1 | 46 | 54 |

| 9 | 20 | 17 | 37 | 16.4 | 54 | 46 |

| 10 | 5 | 11 | 16 | 7 | 31 | 69 |

| 11 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2.2 | 60 | 40 |

| 12 | 14 | 6 | 20 | 8.8 | 70 | 30 |

| 13 | 12 | 14 | 26 | 11.5 | 46 | 54 |

| 14 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1.4 | 33 | 67 |

| Total | 118 | 109 | 227 | 100 | ||

| School year 2022–2023 | ||||||

| 6 | 11 | 10 | 21 | 5.7 | 52.3 | 47.7 |

| 7 | 14 | 32 | 46 | 12.7 | 30.4 | 69.5 |

| 8 | 26 | 13 | 39 | 10.7 | 66.6 | 33.4 |

| 9 | 22 | 24 | 46 | 12.7 | 47.8 | 52.2 |

| 10 | 7 | 15 | 22 | 6.2 | 31.8 | 68.2 |

| 11 | 33 | 3 | 36 | 9.8 | 92 | 8 |

| 12 | 47 | 28 | 75 | 20.6 | 62.6 | 37.4 |

| 13 | 31 | 49 | 80 | 21.6 | 38 | 62 |

| 14 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Total | 191 | 174 | 365 | 100 | ||

| School year 2023–2024 | ||||||

| 6 | 21 | 17 | 38 | 8.7 | 55 | 45 |

| 7 | 37 | 31 | 68 | 15.7 | 54 | 46 |

| 8 | 25 | 28 | 53 | 12.5 | 47 | 53 |

| 9 | 39 | 32 | 71 | 16.3 | 55 | 45 |

| 10 | 33 | 38 | 71 | 16.3 | 46 | 54 |

| 11 | 26 | 25 | 51 | 9.5 | 51 | 49 |

| 12 | 29 | 23 | 52 | 12.2 | 56 | 44 |

| 13 | 16 | 11 | 27 | 6.4 | 59 | 41 |

| 14 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 2.4 | 70 | 30 |

| Total | 233 | 208 | 441 | 100 | ||

| School Year | 2021–2022 | 2022–2023 | 2023–2024 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Hygiene | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| Poor | 127 | 55.9 | 219 | 60 | 308 | 69.9 |

| Good | 100 | 44.1 | 146 | 40 | 133 | 30.1 |

| School Year | 2021–2022 | 2022–2023 | 2023–2024 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental Caries | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| Primary teeth | 78 | 34.4 | 61 | 16.7 | 79 | 17.9 |

| Permanent teeth | 33 | 14.5 | 44 | 12 | 39 | 8.8 |

| Caries-Free | 116 | 51.1 | 260 | 71.3 | 323 | 73.3 |

| School Year | 2021—2022 | 2022—2023 | 2023—2024 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malocclusions | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Class I | 154 | 67.8 | 168 | 46 | 251 | 57 |

| Class II | 66 | 29.1 | 187 | 51.2 | 168 | 38 |

| Class III | 7 | 3.1 | 10 | 2.8 | 22 | 5 |

| Unilateral Cross-bite | 17 | 7.5 | 32 | 8.8 | 46 | 10.4 |

| Bilateral Cross-bite | 8 | 3.5 | 16 | 4.4 | 6 | 1.4 |

| Anterior Cross-bite | 7 | 3.1 | 6 | 1.7 | 16 | 3.6 |

| Scissor-bite | 6 | 2.6 | 11 | 3 | 6 | 1.4 |

| Normal Overjet | 130 | 57.3 | 168 | 46 | 270 | 61 |

| Increased Overjet | 79 | 34.8 | 175 | 49 | 140 | 32 |

| Reduced Overjet | 18 | 7.9 | 21 | 5 | 31 | 7 |

| Normal Overbite | 125 | 55 | 256 | 70 | 280 | 63.5 |

| Increased Overbite | 85 | 37.5 | 95 | 26 | 130 | 29.5 |

| Reduced Overbite | 17 | 7.5 | 14 | 4 | 31 | 7 |

| School Year | 2021–2022 | 2022–2023 | 2023–2024 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral habits | n. | % | n. | % | n. | % |

| Finger | 9 | 3.9 | 15 | 4.1 | 29 | 6.6 |

| Pacifier | 100 | 44 | 112 | 30.7 | 135 | 30.6 |

| Baby bottle | 63 | 27.7 | 62 | 17 | 91 | 20.6 |

| Bruxism | 53 | 23.3 | 26 | 7.1 | 72 | 16.3 |

| Oral breathing | 54 | 23.7 | 30 | 8.2 | 47 | 10.6 |

| Onychophagy | 6 | 2.60 | 50 | 13.7 | 124 | 28 |

| Poor oral hygiene | Caries in primary teeth | 0.002 * |

| Poor oral hygiene | Caries in permanent teeth | 0.01 * |

| Poor oral hygiene | Dental crowding | 0.001 * |

| Caries in primary teeth | Oral breathing | 0.001 * |

| Caries in primary teeth | Pacifier sucking | 0.001 * |

| Caries in permanent teeth | Dental crowding | 0.01 * |

| Class III malocclusion | Oral breathing | 0.002 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laganà, G.; Lione, R.; Malara, A.; Fanelli, S.; Fabi, F.; Cozza, P. Oro-Functional Conditions in a 6-to-14-Year-Old School Children Population in Rome: An Epidemiological Study. Children 2025, 12, 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030305

Laganà G, Lione R, Malara A, Fanelli S, Fabi F, Cozza P. Oro-Functional Conditions in a 6-to-14-Year-Old School Children Population in Rome: An Epidemiological Study. Children. 2025; 12(3):305. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030305

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaganà, Giuseppina, Roberta Lione, Arianna Malara, Silvia Fanelli, Francesco Fabi, and Paola Cozza. 2025. "Oro-Functional Conditions in a 6-to-14-Year-Old School Children Population in Rome: An Epidemiological Study" Children 12, no. 3: 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030305

APA StyleLaganà, G., Lione, R., Malara, A., Fanelli, S., Fabi, F., & Cozza, P. (2025). Oro-Functional Conditions in a 6-to-14-Year-Old School Children Population in Rome: An Epidemiological Study. Children, 12(3), 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12030305