Enhancing Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants Through the Sensory Development Care Map

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

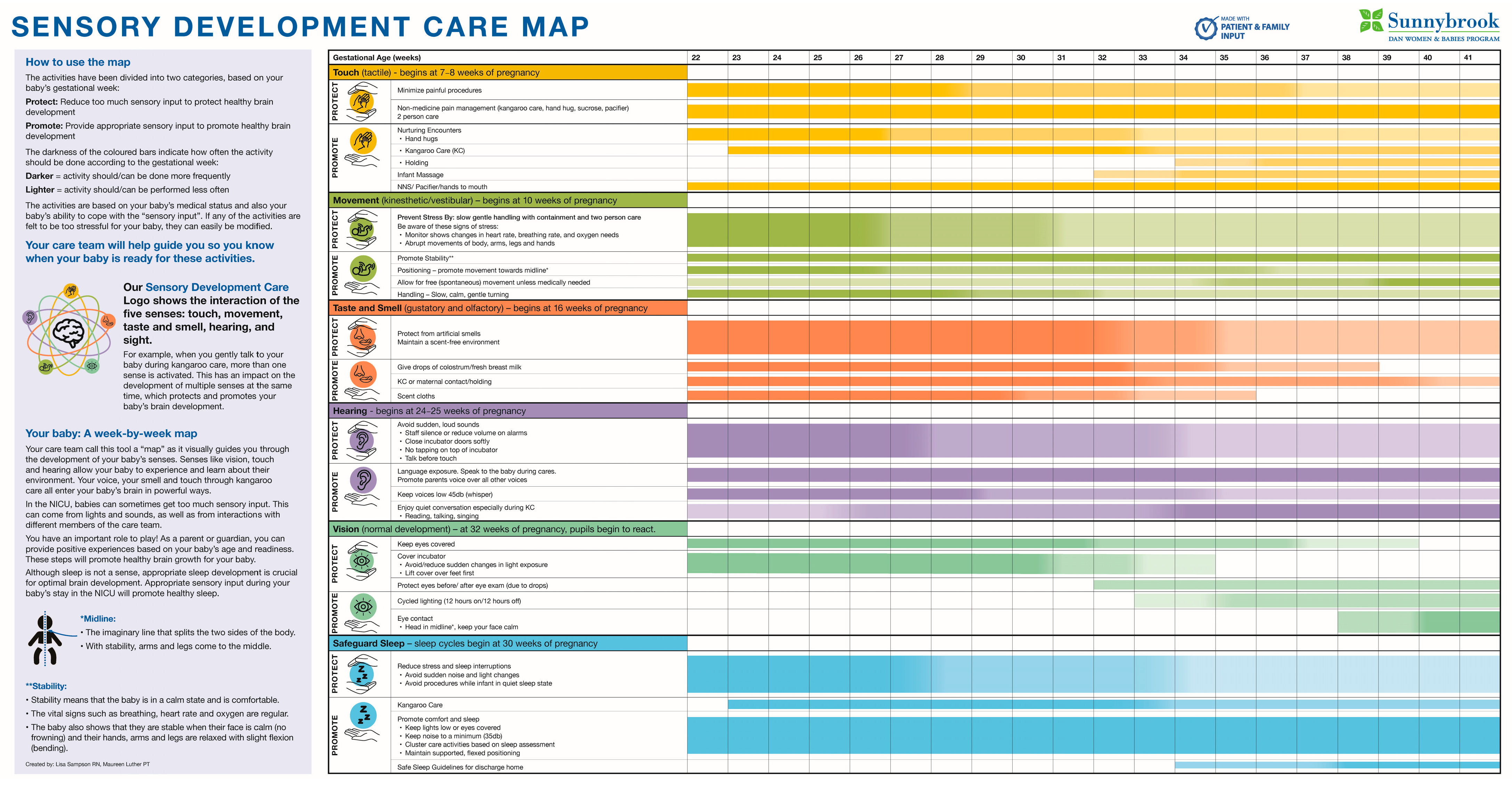

2.1. Building the Sensory Development Care Map (SDCM)

2.2. Measurements

3. Results

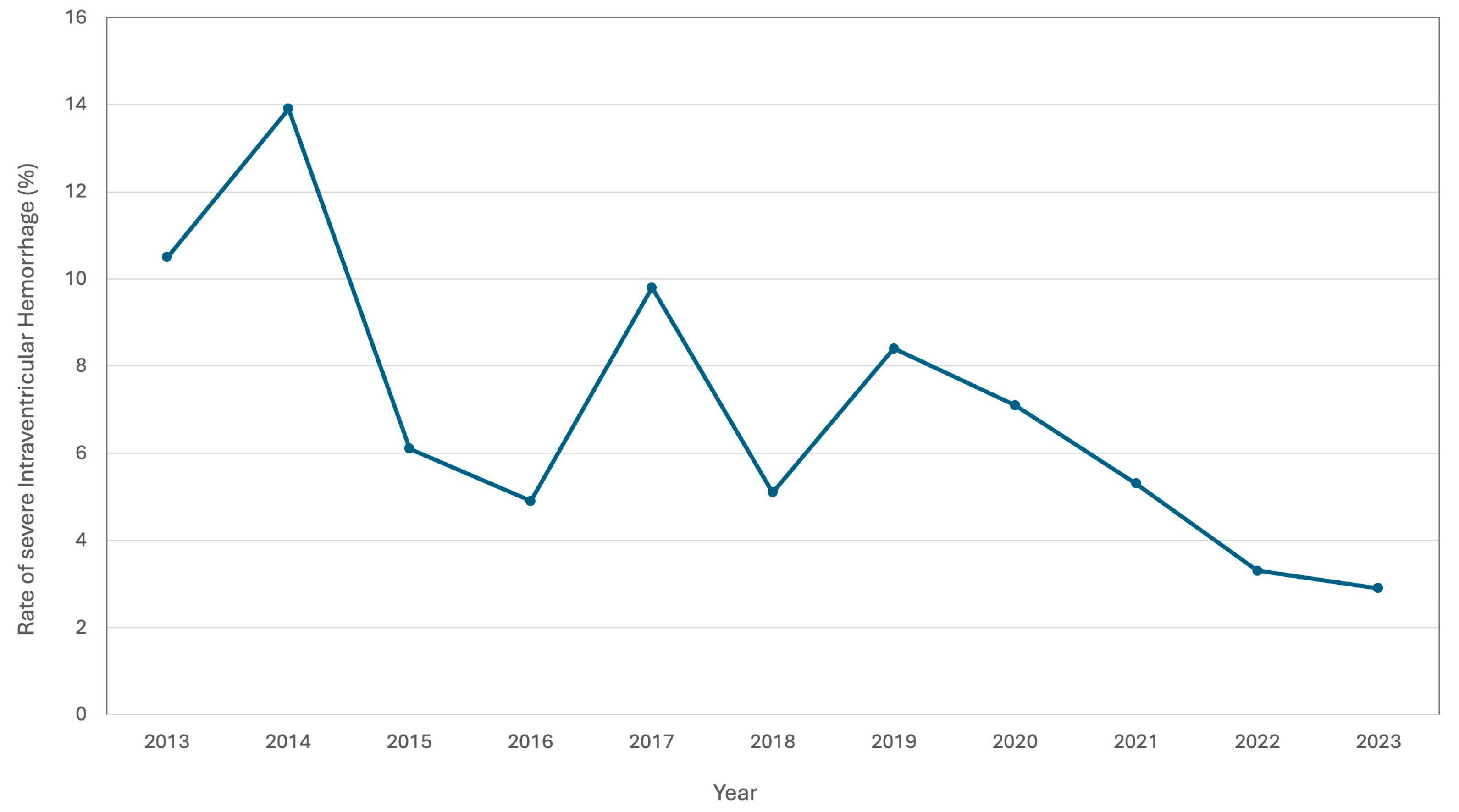

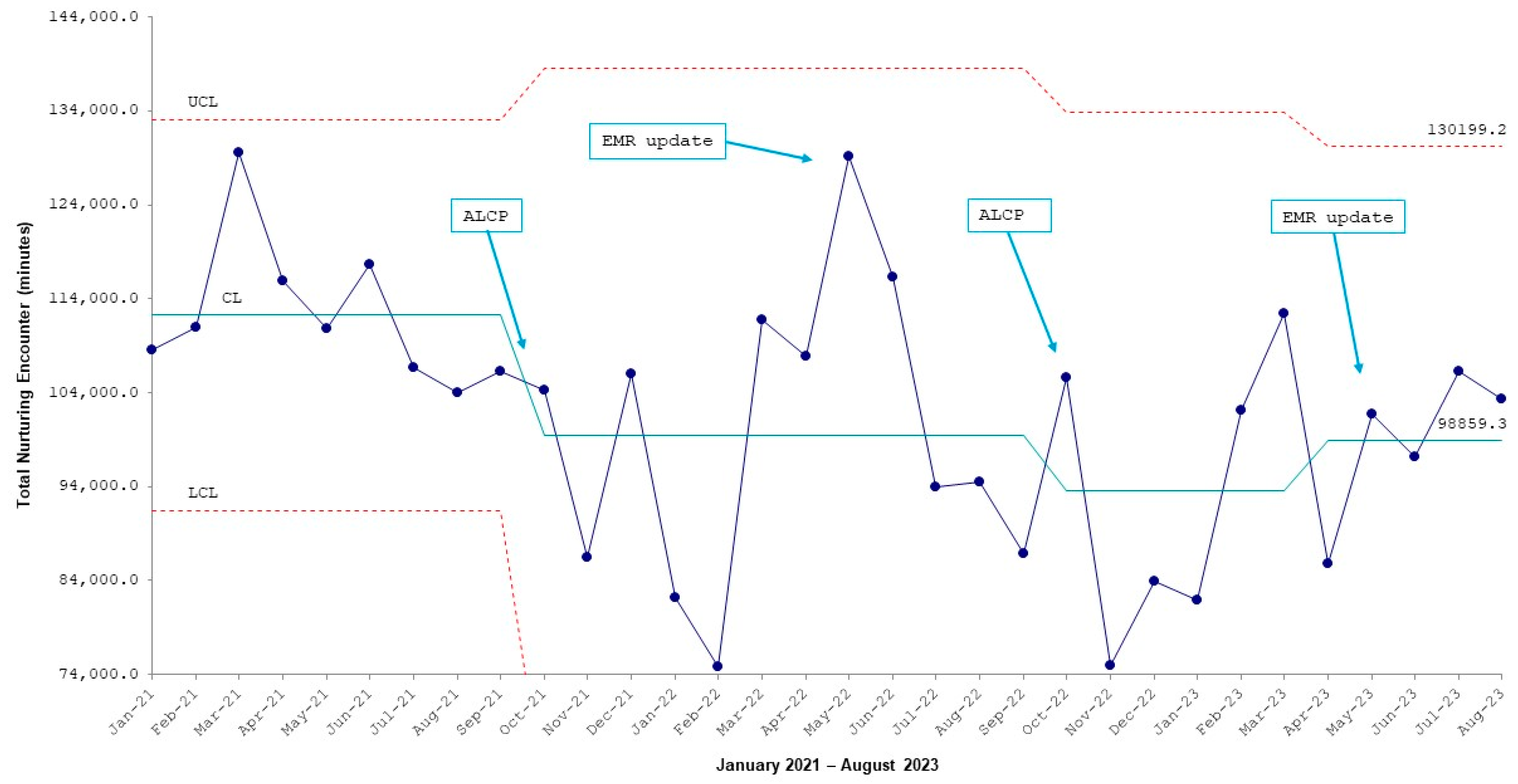

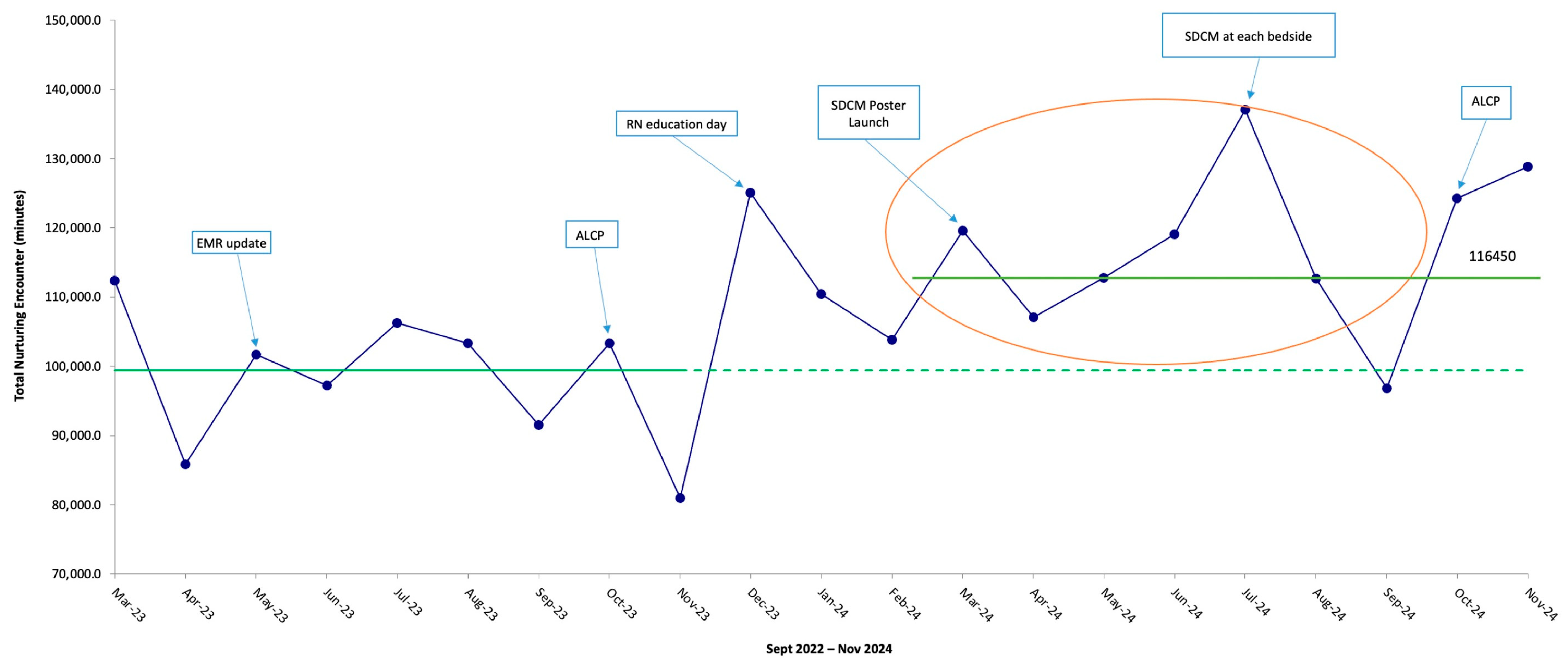

3.1. Results of the NE Audits Prior to Implementation of the SDCM

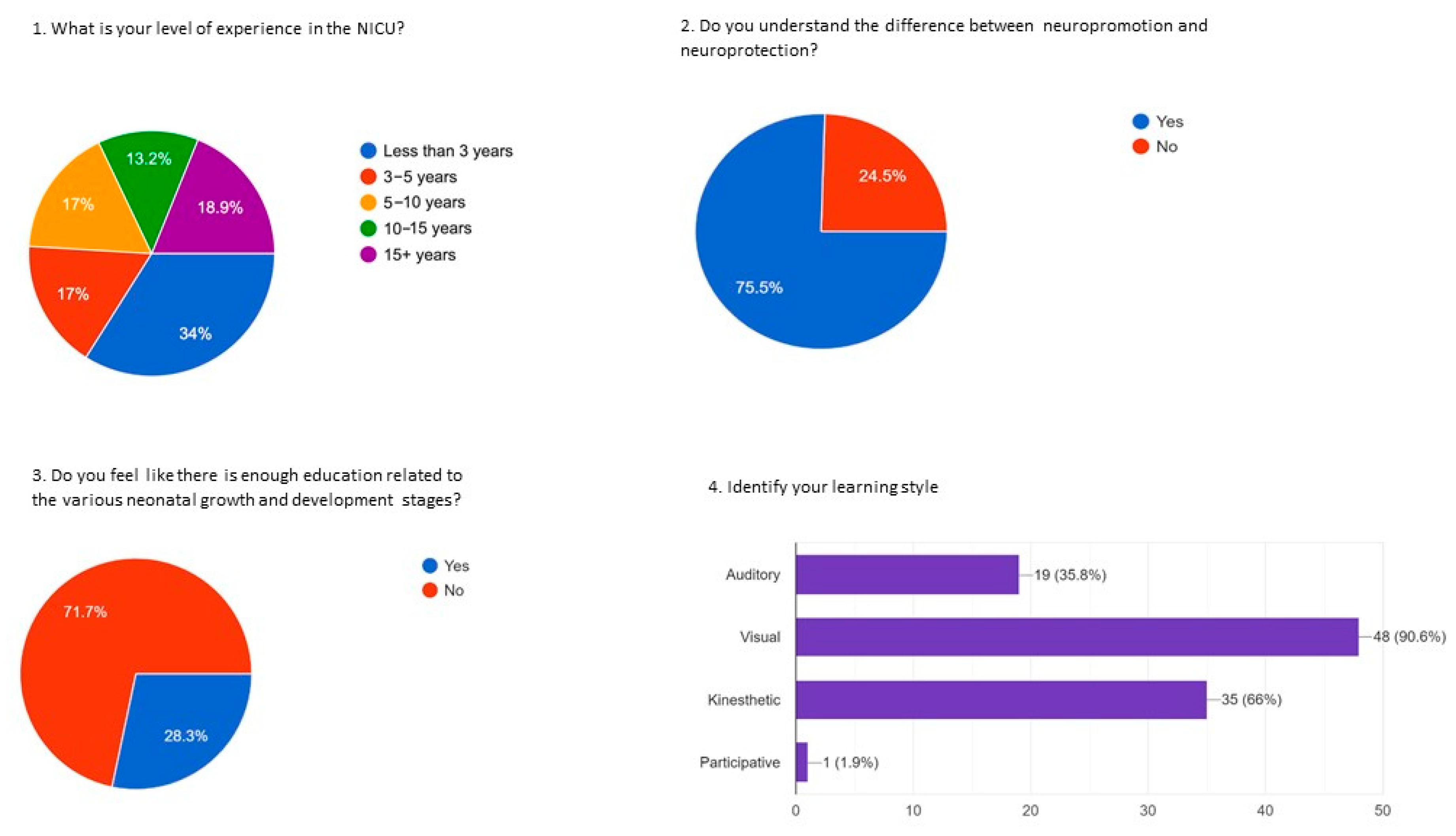

3.2. Results of the Nursing Staff Survey on NEs

3.3. Results of the Parent Survey on NE

3.4. Results of the SDCM Pre-Implementation Survey

3.5. Results of the SDCM Post-Implementation Survey with Staff and Families (Ongoing)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| NE | Nurturing Encounters |

| GA | Gestational Age |

| SDCM | Sensory Development Care Map |

| PDSA | Plan-Do-Study-Act |

| Portable Document Format | |

| EMR | electronic medical records |

| QR | quick response |

References

- Ellsbury, D.L.; Clark, R.H. Does quality improvement work in neonatology improve clinical outcomes? Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2017, 29, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.K.; Beltempo, M.; McMillan, D.D.; Seshia, M.; Singhal, N.; Dow, K.; Aziz, K.; Piedboeuf, B.; Shah, P.S. Outcomes and care practices for preterm infants born at less than 33 weeks’ gestation: A quality-improvement study. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E81–E91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.F.; Laudert, S.; Perkins, B.; Macmillan-York, E.; Martin, S.; Graven, S. The development of potentially better practices to support the neurodevelopment of infants in the NICU. J. Perinatol. 2007, 27 (Suppl. S2), S48–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.G. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2023, 66, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Rosa, V.L.; Gerraci, A.; Lacono, A.; Commodari, E. Affective touch in preterm infant development: Neurobiological mechanisms and implications for child-caregiver attachment and neonatal care. Children 2024, 11, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, P.T.; Grunau, R.E.; Mirea, L.; Petrie, J.; Soraisham, A.S.; Synnes, A.; Ye, X.Y.; O’Brien, K. Family Integrated Care (FICare): Positive impact on behavioural outcomes at 18 months. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 151, 105196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Robson, K.; Bracht, M.; Cruz, M.; Lui, K.; Alvaro, R.; da Silva, O.; Monterrosa, L.; Narvey, M.; Ng, E.; et al. Effectiveness of Family Integrated Care in neonatal intensive care units on infant and parent outcomes: A multicentre, multinational, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pados, B.F. Physiology of Stress and Use of Skin-to-Skin Care as a Stress-Reducing Intervention in the NICU. Nurs. Women's Health 2019, 23, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliades, C. Mitigating Infant Medical Trauma in the NICU: Skin-to-Skin Contact as a Trauma-Informed, Age-Appropriate Best Practice. Neonatal Netw. 2018, 37, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picciolini, O.; Porro, M.; Meazza, A.; Giannì, M.L.; Rivoli, C.; Lucco, G.; Barretta, F.; Bonzini, M.; Mosca, F. Early exposure to maternal voice: Effects on preterm infants development. Early Hum. Dev. 2014, 90, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippa, M.; Panza, C.; Ferrari, F.; Frassoldati, R.; Kuhn, P.; Balduzzi, S.; D’Amico, R. Systematic review of maternal voice interventions demonstrates increased stability in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippa, M.; Lordier, L.; De Almeida, J.S.; Monaci, M.G.; Adam-Darque, A.; Grandjean, D.; Kuhn, P.; Hüppi, P.S. Early vocal contact and music in the NICU: New insights into preventive interventions. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 87, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liaw, J.J. Tactile stimulation and preterm infants. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2000, 14, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, M.S.; Funk, S.G.; Carlson, J. Parental Stressor Scale: Neonatal intensive care unit. Nurs. Res. 1993, 42, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickliter, R. The integrated development of sensory organization. Clin. Perinatol. 2011, 38, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummelte, S.; Grunau, R.E.; Chau, V.; Poskitt, K.J.; Brant, R.; Vinall, J.; Gover, A.; Synnes, A.R.; Miller, S.P. Procedural pain and brain development in premature newborns. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 71, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, N.H.; Bachman, J.; Jenkins, R.; Chen, C.H.; Chang, Y.C.; Chang, Y.S.; Wang, T.-M. Relationships between environmental stressors and stress biobehavioral responses of preterm infants in NICU. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2009, 23, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.C.; Gutovich, J.; Smyser, C.; Pineda, R.; Newnham, C.; Tjoeng, T.H.; Vavasseur, C.; Wallendorf, M.; Neil, J.; Inder, T. Neonatal intensive care unit stress is associated with brain development in preterm infants. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 70, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, J.J. Dysmaturation of Premature Brain: Importance, Cellular Mechanisms, and Potential Interventions. Pediatr. Neurol. 2019, 95, 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, K.; McGill, G.; Ann Waitzman, K.; Powell, J.; Carlson, M.; Shaffer, G.; Morris, M. Collaboration to Improve Neuroprotection and Neuropromotion in the NICU: Team Education and Family Engagement. Neonatal Netw. 2021, 40, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadders-Algra, M. Challenges and limitations in early intervention. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2011, 53 (Suppl. S4), 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhbari Ziegler, S.; Hadders-Algra, M. Coaching approaches in early intervention and paediatric rehabilitation. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2020, 62, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Comment |

|---|

| “[We would like] information about the development all of these senses and what is the appropriate time (weeks) to get started” |

| “How can we start developing these senses and the activities needed to be done (as parents)?” |

| “How can we track progress on these developments?” |

| “[We would like] information on how to help our baby’s senses and what not to do” |

| “Provide information on weekly milestones; impact of [intensive care] on development.” |

| “Nurses inform us and guide us” |

| Comment |

|---|

| “I refer to it all the time. I don't want a ton of written material.” |

| “I like the map in the hallway too because I can focus on it away from the bedside.” |

| “I Would like someone to speak to me about what I am reading” |

| “It’s very helpful” |

| “I find it confusing with all the colours” |

| “If someone had told me about it right away, that would have been good.” |

| “First family meeting would be a good time to discuss the map.” |

| “The first week is overwhelming, so after that is better to go through the map.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sampson, L.; Luther, M.; Rolnitsky, A.; Ng, E. Enhancing Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants Through the Sensory Development Care Map. Children 2025, 12, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12020192

Sampson L, Luther M, Rolnitsky A, Ng E. Enhancing Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants Through the Sensory Development Care Map. Children. 2025; 12(2):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12020192

Chicago/Turabian StyleSampson, Lisa, Maureen Luther, Asaph Rolnitsky, and Eugene Ng. 2025. "Enhancing Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants Through the Sensory Development Care Map" Children 12, no. 2: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12020192

APA StyleSampson, L., Luther, M., Rolnitsky, A., & Ng, E. (2025). Enhancing Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants Through the Sensory Development Care Map. Children, 12(2), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12020192