The Analysis of the Clinical Course of Acute Pancreatitis in Children—A Single-Center Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Study Group

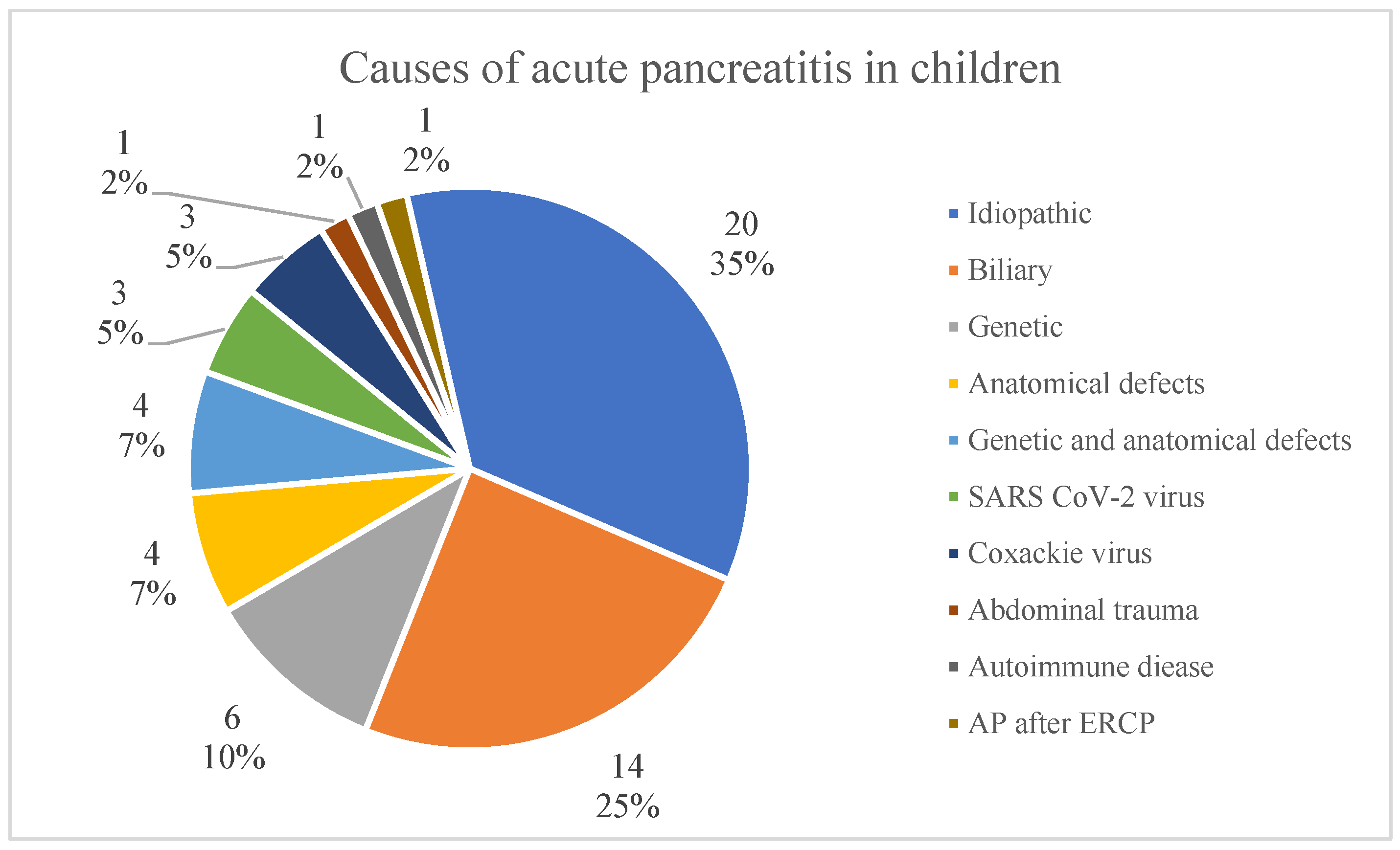

3.2. Ethiopathogenesis

3.3. Symptoms of Acute Pancreatits

3.4. Acute Pancreatitis Course and Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Taking into account previous data from the gastroenterology decreased, the number of children diagnosed with acute pancreatitis increased over time.

- The most frequent causes are genetic predispositions, anatomical defects and cholelithiasis; however, in up to 35%, which is the majority of cases, the cause remains unidentified. The results show the necessity of further investigation on AP and finding the other reasons of morbidity.

- Acute pancreatitis should be considered in every case of stomachache, vomiting and jaundice in children.

- It seems that obesity and high inflammatory parameters on admission are risk factors for the severe course of the condition.

6. Limits

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szatmary, P.; Grammatikopoulos, T.; Cai, W.; Huang, W.; Mukherjee, R.; Halloran, C.; Beyer, G.; Sutton, R. Acute Pancreatitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Drugs 2022, 82, 1251–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannuzzi, J.P.; King, J.A.; Leong, J.H.; Quan, J.; Windsor, J.W.; Tanyingoh, D.; Coward, S.; Forbes, N.; Heitman, S.J.; Shaheen, A.-A.; et al. Global Incidence of Acute Pancreatitis Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.Z.; Freeman, A.J. Pancreatitis in Children. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 1273–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandalia, A.; Wamsteker, E.J.; DiMagno, M.J. Recent advances in understanding and managing acute pancreatitis. F1000Res 2019, 7, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkowska, J.; Zielinska, N.; Tubbs, R.S.; Podgórski, M.; Dłubek-Ruxer, J.; Olewnik, Ł. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Pancreatitis. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morinville, V.D.; Husain, S.Z.; Bai, H.; Barth, B.; Alhosh, R.; Durie, P.R.; Freedman, S.D.; Himes, R.; Lowe, M.E.; Pohl, J.; et al. Definitions of Pediatric Pancreatitis and Survey of Present Clinical Practices. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 55, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, M.S.; Yadav, D. Global epidemiology and holistic prevention of pancreatitis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Lowe, M.; Husain, S. What have we learned about acute pancreatitis in children? J. Ped Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2011, 52, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U.; Jasielska, M.; Flak-Wancerz, A.; Więcek, S.; Gruszczyńska, K.; Chlebowczyk, W.; Woś, H. Acute pancreatitis in children. Przegl Gastroenterol. 2018, 13, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Chao, H.; Kong, M.; Hsia, S.; Lai, M.; Yan, D. Acute pancreatitis in children. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werlin, S.; Kugathasan, S.; Frautschy, B. Pancreatitis in children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2003, 37, 591–5952003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Orkin, S.H.; Trout, A.T.; Fei, L.; Lin, T.K.; Nathan, J.D.; Thompson, T.; Vitale, D.S.; Abu-El-Haija, M. Sensitivity of biochemical and imaging findings for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in children. J. Pediatr. 2019, 213, 143–148.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffey, M.; Ooi, C. Paediatric pancreatic diseases. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2020, 56, 1694–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samies, N.L.; Yarbrough, A.; Boppana, S. Pancreatitis in pediatric patients with COVID-19. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2020, 10, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artunduaga, M.; Grover, A.; Callahan, M. Acute pancreatitis in children: A review with clinical perspectives to enhance imaging interpretation. Pediatr. Radiol. 2021, 51, 1970–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-El-Haija, M.; Kumar, S.; Quiros, J.A.; Balakrishnan, K.; Barth, B.; Bitton, S.; Eisses, J.F.; Foglio, E.J.; Fox, V.; Francis, D.; et al. Management of acute pancreatitis in the pediatric population: A Clinical report from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Pancreas Committee. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Amp; Nutr. 2018, 66, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinath, A.; Lowe, M. Pediatric pancreatitis. Pediatr. Rev. 2013, 34, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uc, A.; Husain, S. Pancreatitis in children. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca Sepúlveda, E.; Guerrero-Lozano, R. Acute pancreatitis and recurrent acute pancreatitis: An exploration of clinical and etiologic factors and outcomes. J. Pediatr. 2019, 95, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ramírez, C.; Larrosa-Haro, A.; Flores-Martínez, S.; Sánchez-Corona, J.; Villa-Gómez, A.; Macías-Rosales, R. Acute and recurrent pancreatitis in children: Etiological factors. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 96, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Minowa, K.; Isayama, H.; Shimizu, T. Acute recurrent and chronic pancreatitis in children. Pediatr. Int. 2021, 63, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uc, A.; Zimmerman, M.B.; Wilschanski, M.M.; Werlin, S.L.; Troendle, D.; Shah, U.M.; Schwarzenberg, S.J.; Rhee, S.; Pohl, J.F.; Perito, E.R.; et al. Impact of Obesity on Pediatric Acute Recurrent and Chronic Pancreatitis. Pancreas 2018, 47, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatua, B.; El-Kurdi, B.; Singh, V.P. Obesity and pancreatitis. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 33, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, H.; Melling, J.; Jones, M.; Melling, C. C-reactive protein accurately predicts severity of acute pancreatitis in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 57, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, L.; Long, G.; Chen, B.; Shu, X.; Jiang, M. Amalgamation of systemic inflammatory response syndrome score with C-reactive protein level in evaluating acute pancreatitis severity in children. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, M.; Qi, X.; Xu, Z.; Cai, Q.; Sheng, H.; Chen, E.; Zhao, B.; et al. Leukocyte cell population data from the blood cell analyzer as a predictive marker for severity of acute pancreatitis. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2021, 35, e23863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, E.; Ozcan, H.N.; Gulsen, H.H.; Yavuz, O.O.; Seber, T.; Gumus, E.; Oguz, B.; Haliloglu, M. Acute Pancreatitis and Acute Recurrent Pancreatitis in Children: Imaging Findings and Outcomes. Turk. Arch. Pediatr. 2023, 58, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolka, V.; Rohanova, M.; Seda, M.; Karaskova, E.; Tkachyk, O.; Zapalka, M.; Volejnikova, J. Etiology and classification of acute pancreatitis in children admitted to ICU using the Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA) score. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2023, 22, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, M. Pancreatitis and pancreatic trauma. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2005, 14, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, J.; Uc, A. Paediatric pancreatitis. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2015, 31, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başkocagil, E.; Gümüş, M.; Yorulmaz, A.; Emiroğlu, H.H. Retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics, diagnosis, treatment and complications of children with acute pancreatitis: Single-center results. J. Med. Palliat. Care 2023, 4, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautz, T.B.; Chin, A.C.; Radhakrishnan, J. Acute pancreatitis in children: Spectrum of disease and predictors of severity. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 46, 1144–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trout, A.T.; Anupindi, S.A.; Freeman, A.J.; Macias-Flores, J.A.; Martinez, J.A.; Parashette, K.R.; Shah, U.; Squires, J.H.; Morinville, V.D.; Husain, S.Z.; et al. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition and the Society for Pediatric Radiology Joint Position Paper on noninvasive imaging of pediatric pancreatitis: Literature Summary and Recommendations. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 72, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raizner, A.; Phatak, U.P.; Baker, K.; Patel, M.G.; Husain, S.Z.; Pashankar, D.S. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis in children. J. Pediatr. 2013, 162, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable/Parameters | Total (n = 57) | Female (n = 28, 49%) | Male (n = 29, 51%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 11 (SD = 5.0, 2–18) | 11 (SD = 4.8, 3–18) | 10 (SD = 5.1, 2–18) | 0.243 |

| 0–5 years | 13 (22.8%) | 4 (14.3%) | 9 (31%) | 0.307 |

| 6–10 years | 12 (21.1%) | 7 (25%) | 5 (17.2%) | |

| >10 years | 32 (56.1%) | 17 (60.7%) | 15 (51.7%) | |

| BMI (pc) | 50 (SD = 35.9, 1–99) | 53 (SD = 37.5, 2–99) | 49 (34.6, 1–97) | 0.431 |

| Underweight (≤5 pc) | 9 (15.8%) | 5 (17.9%) | 4 (13.8%) | 0.693 |

| Normal weight (6–84 pc) | 33 (57.9%) | 14 (50%) | 19 (65.5%) | |

| Overweight (85–94 pc) | 5 (8.8%) | 3 (10.7%) | 2 (6.9%) | |

| Obese (≧95 pc) | 10 (17.5%) | 6 (21.4%) | 4 (13.8%) | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 7 (12.3%) | 2 (7.1%) | 5 (17.2%) | 1.000 |

| Familial history of pancreatic disease | 5 (8.8%) | 3 (10.7%) | 2 (6.9%) | 0.670 |

| More than 1 AP episode | 19 (33.3%) | 9 (32.1%) | 10 (34.5%) | 0.851 |

| 1 episode | 38 (66.7%) | 19 (67.9%) | 19 (65.5%) | 0.501 |

| 2 episodes | 10 (17.5%) | 6 (21.4%) | 4 (13.8%) | |

| >2 episodes | 9 (15.8%) | 3 (10.7%) | 6 (20.7%) | |

| Age of the first AP episode (years) | 10 (SD = 5.1, 1–18) | 11 (SD = 5.4, 1–18) | 10 (SD = 4.9, 2–18) | 0.231 |

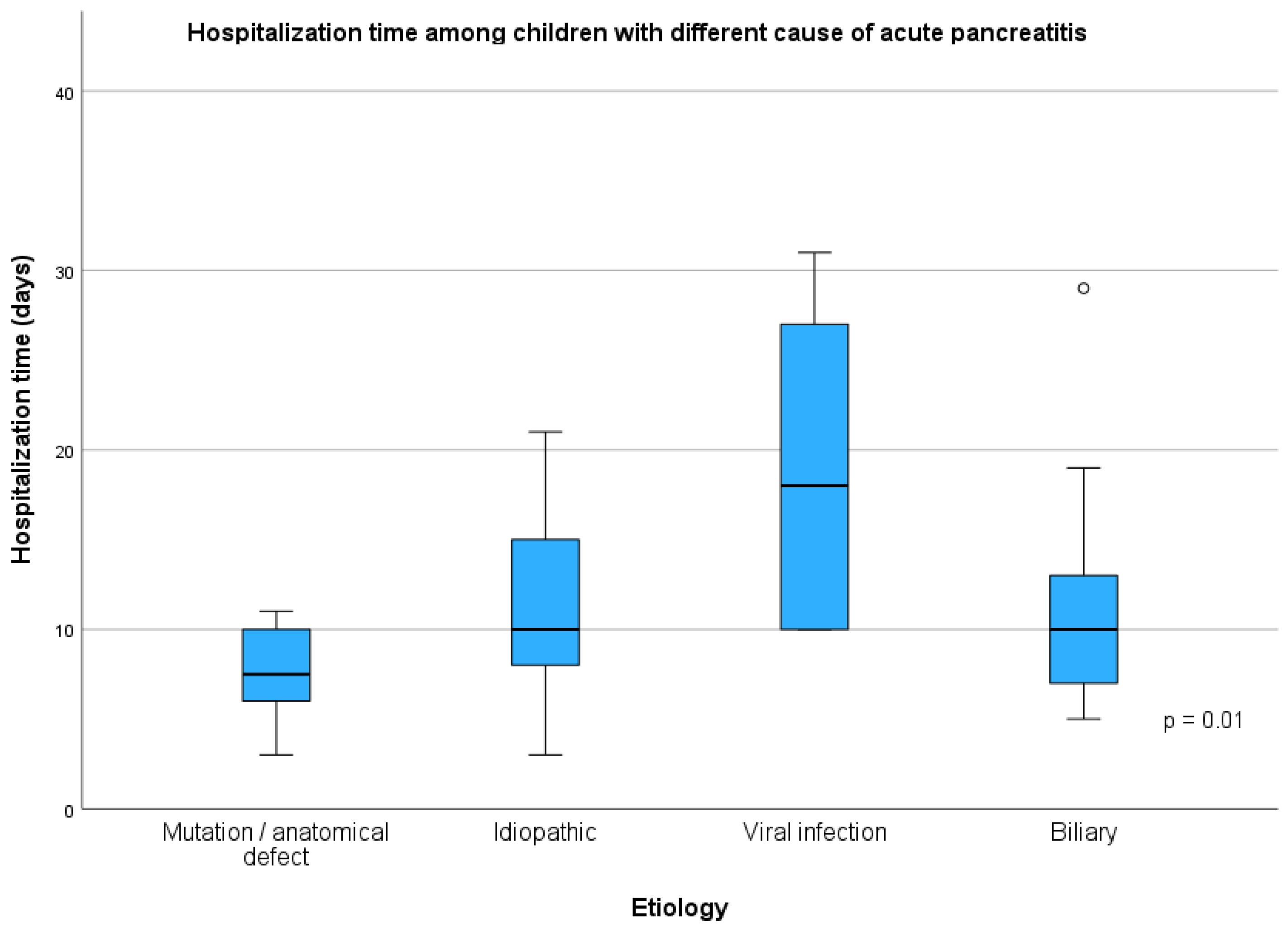

| Variable | Mutation and/or Anatomical Defects (1, n = 14) | Idiopathic (2, n = 20) | Infectious (3, n = 6) | Biliary (4, n = 14) | p | p Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 6 (42.9%) | 8 (40%) | 2 (33.3%) | 12 (85.7%) | 0.029 | 1 vs. 2 = 0.868 1 vs. 3 = 1.000 1 vs. 4 = 0.046 2 vs. 3 = 1.000 2 vs. 4 = 0.013 3 vs. 4 = 0.037 |

| Age (years) | 10 (8.1 years) | 7 (11.0 years) | 13 (4.3 years) | 14 (5.5 years) | 0.124 | |

| Age of the first AP episode (years) | 8 (8.0 years) | 7 (12.0 years) | 12 (3.6 years) | 14 (4.8 years) | 0.059 | |

| BMI (pc) | 50 (57.0 pc) | 40 (64.0 pc) | 73 (43.0 pc) | 95 (46.0 pc) | 0.004 | 1 vs. 2 = 1.000 1 vs. 3 = 1.000 1 vs. 4 = 0.030 2 vs. 3 = 0.671 2 vs. 4 = 0.004 3 vs. 4 = 1.000 |

| Number of AP episodes | 2 (3.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (0) | <0.001 | 1 vs. 2 = 0.012 1 vs. 3 = 0.530 1 vs. 4 = 0.033 2 vs. 3 = 0.415 vs. 4 = 1.000 3 vs. 4 = 1.000 |

| Duration of hospitalization (days) | 8 (4.0 days) | 10 (8.0 days) | 18 (18.0 days) | 10 (6.0 days) | 0.010 | 1 vs. 2 = 0.279 1 vs. 3 = 0.006 1 vs. 4 = 0.387 2 vs. 3 = 0.385 2 vs. 4 = 1.000 3 vs. 4 = 0.393 |

| Severe AP course (number) | 2 (14.3%) | 2 (10%) | 2 (33.3%) | 3 (21.4%) | 0.655 |

| Total (57) | Severe Course (9/57, 15.8%) | Non-Severe Course (48/57, 84.2%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 28/57 (49%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | 24/48 (50%) | 1.000 |

| Age (years) | 11 (SD = 5.0) | 12 (IQR = 6.5) | 12 (IQR = 9.8) | 1.000 |

| Age of the first AP episode (years) | 10 (SD = 5.1) | 12 (IQR = 6.4) | 11 (IQR = 9.3) | 0.891 |

| BMI (pc) | 52 (IQR = 75) | 93 (IQR = 46) | 48 (IQR = 66) | 0.031 |

| Obesity | 10/57 (17.5%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | 6/48 (12.5%) | 0.044 |

| Number of AP episodes | 1 (IQR = 1) | 1 (IQR = 0) | 1 (IQR = 1) | 1.000 |

| Duration of hospitalization (days) | 11 (SD = 6.2) | 20 (IQR = 14) | 9 (IQR = 4) | <0.001 |

| Etiology | 20/57 (25%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | 18/48 (37.5%) | 0.379 |

| - Idiopathic | 14/57 (25%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | 11/48 (22.9%) | |

| - Biliary | 14/57 (25%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | 13/48 (27.1%) | |

| - Genetic mutation or anatomical defect | 3/57 (5%) | 0/9 | 3/48 (6.3%) | |

| - Infectious SARS-CoV-2 or Coxackie virus | 3/57 (5%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | 1/48 (2.1%) | |

| - Abdominal trauma | 1/57 (2%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | 0/48 (0%) | |

| - Autoimmune disease | 1/57 (2%) | 0/9 | 1/48 (2.1%) | |

| - AP after ERCP | 1/57 (2%) | 0/9 | 1/48 (2.1%) | |

| Diagnostic imaging | ||||

| - USG | 57/57 (100%) | 9/9 (100%) | 48/48 (100%) | |

| - Abdominal CT | 16/57 (28.1%) | 9/9 (100%) | 7/48 (14.6%) | <0.001 |

| - MR | 17/57 (29.8%) | 5/9 (55.6%) | 12/48 (25%) | 0.112 |

| Laboratory test results | ||||

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 41 (SD = 3.9) | 39 (IQR = 5) | 40 (IQR = 4.7) | 0.183 |

| ALT (U/L) | 26 (IQR = 105) | 31 (IQR = 112) | 24 (IQR = 104) | 0.829 |

| AST (U/L) | 35 (IQR = 49) | 41 (IQR = 37) | 35 (IQR = 71) | 0.763 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 515 (IQR = 850) | 302 (IQR = 719) | 521 (IQR = 841.3) | 0.538 |

| Amylase after 48 h (U/L) | 165 (IQR = 309) | 104 (IQR = 677) | 174 (IQR = 299) | 0.732 |

| Lipase (U/L) | 772 (IQR = 1954) | 473 (IQR = 821) | 826 (IQR = 1958) | 0.560 |

| Bilirubin (U/L) | 16 (IQR = 18.8) | 15 (IQR = 17.8) | 16 (IQR = 22.7) | 0.861 |

| AF (U/L) | 172 (IQR = 77) | 180 (IQR = 77.8) | 158 (IQR = 99.5) | 0.886 |

| GGTP (U/L) | 20 (IQR = 84) | 28 (IQR = 76) | 19 (IQR = 97.5) | 0.913 |

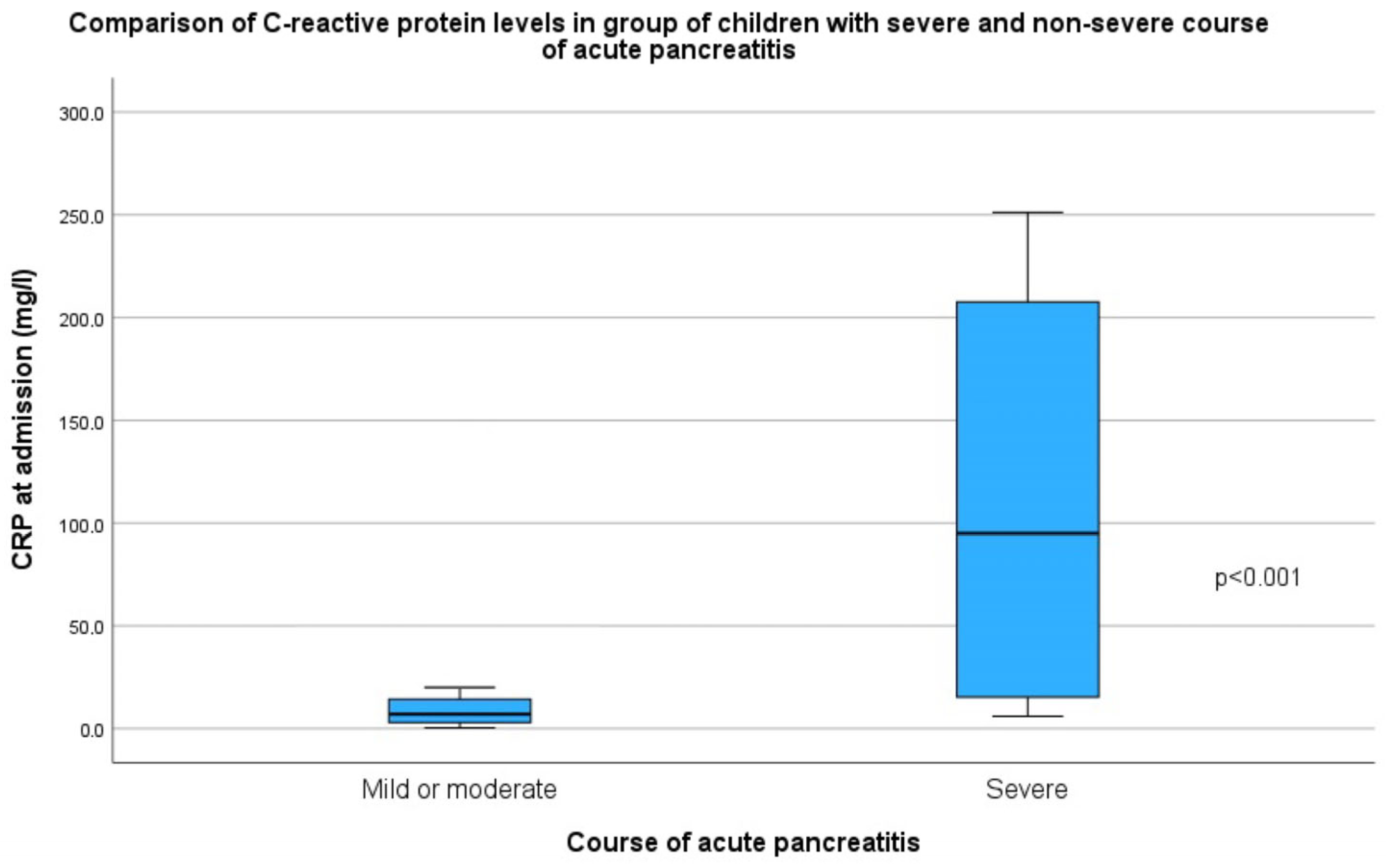

| CRP at admission (mg/L) | 8 (IQR = 17.2) | 119 (IQR = 201.3) | 6 (IQR = 11) | <0.001 |

| CRP after 48 h (mg/L) | 10 (IQR = 67.5) | 147 (IQR = 197.2) | 8 (IQR = 18.5) | 0.002 |

| Highest CRP during hospital stay (mg/L) | 20 (IQR = 93.4) | 208 (IQR = 161.1) | 14 (IQR = 61.1) | <0.001 |

| WBC | 9 (IQR = 4.1) | 16 (SD = 6.9) | 9 (SD = 3) | 0.016 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 84 (IQR = 56) | 95 (IQR = 24) | 80 (IQR = 68) | 0.832 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 144 (SD = 37.5) | 151 (SD = 48.2) | 142 (SD = 35.2) | 0.678 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Parenteral feeding | 14/57 (24.6%) | 8/9 (88.9%) | 6/48 (12.5%) | <0.001 |

| Cholecystectomy | 2/57 (3.5%) | 0/9 (0%) | 2/48 (4.2%) | 1.000 |

| ERCP | 6/57 (10.5%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | 5/48 (10.4%) | 1.000 |

| Complications | 9/57 (15.8%) | 6/9 (66.7%) | 3/48 (6.3%) | <0.001 |

| Necrosis | 4/57 (7.0%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | 0/48 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Peripancreatic fluid collections | 6/57 (10.5%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | 2/48 (4.2%) | 0.004 |

| Pleural effusion | 2/57 (3.5%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | 1/48 (2.1%) | 0.298 |

| Pancreatic pseudocyst | 2/57 (3.5%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | 0/48 (0%) | 0.023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mroskowiak, A.; Majewska, K.; Symela, Z.; Rabstein, D.; Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U.; Więcek, S. The Analysis of the Clinical Course of Acute Pancreatitis in Children—A Single-Center Study. Children 2025, 12, 1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121665

Mroskowiak A, Majewska K, Symela Z, Rabstein D, Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U, Więcek S. The Analysis of the Clinical Course of Acute Pancreatitis in Children—A Single-Center Study. Children. 2025; 12(12):1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121665

Chicago/Turabian StyleMroskowiak, Aleksandra, Karolina Majewska, Zuzanna Symela, Dominik Rabstein, Urszula Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, and Sabina Więcek. 2025. "The Analysis of the Clinical Course of Acute Pancreatitis in Children—A Single-Center Study" Children 12, no. 12: 1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121665

APA StyleMroskowiak, A., Majewska, K., Symela, Z., Rabstein, D., Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U., & Więcek, S. (2025). The Analysis of the Clinical Course of Acute Pancreatitis in Children—A Single-Center Study. Children, 12(12), 1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12121665