Occupation-Based Tele-Intervention for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Pilot Study

Highlights

- Tele-CO-OP enables meaningful functional gains in children with NDDs through telehealth.

- Home-based delivery enhances the generalization of treatment to the child’s natural environment.

- Key facilitators and barriers identified can inform sustainable teleintervention.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

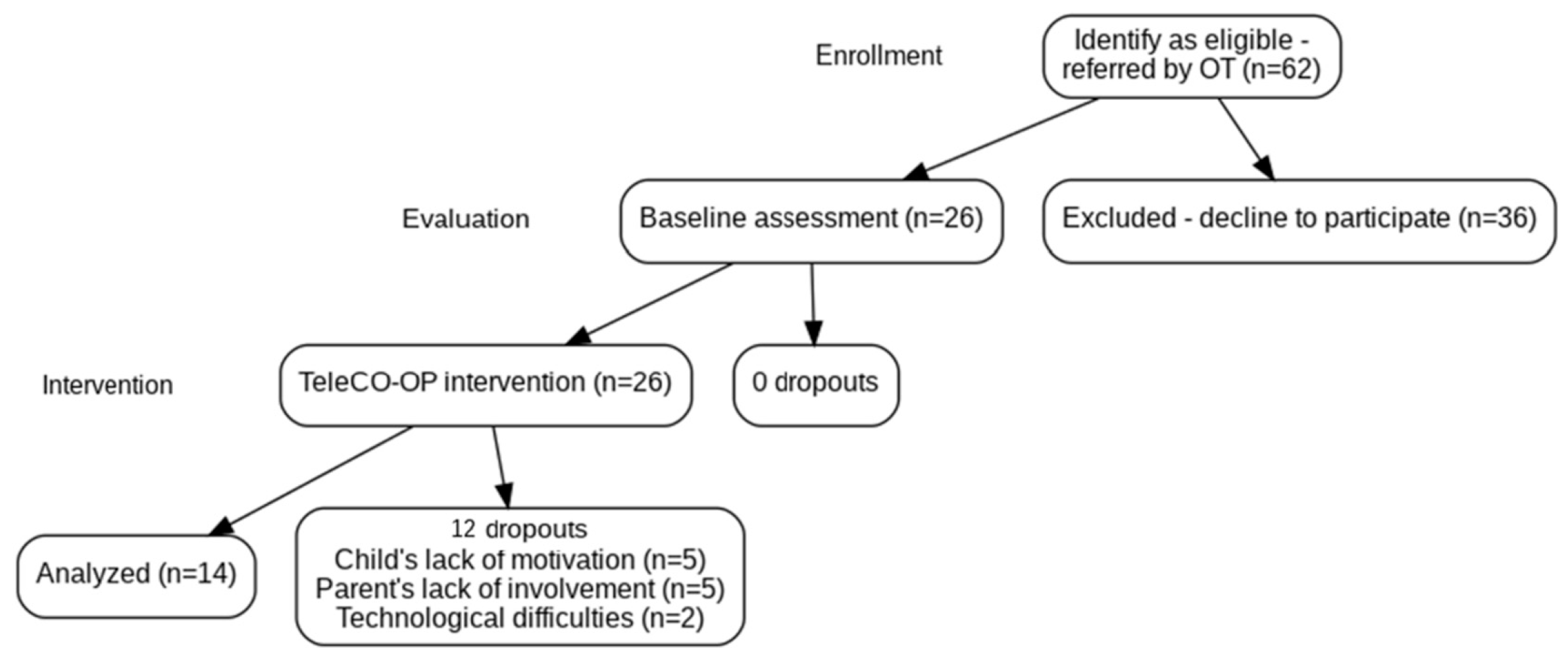

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Socio-Demographic Questionnaire and Clinical Data

2.3.2. Therapist Feasibility Log

2.3.3. Parents as Partners in Intervention—Satisfaction Questionnaire [PAPI-Q; [40]]

2.3.4. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), 5th Edition [41]

2.3.5. Performance Quality Rating Scale [PQRS; [45]]

2.4. Focus Groups

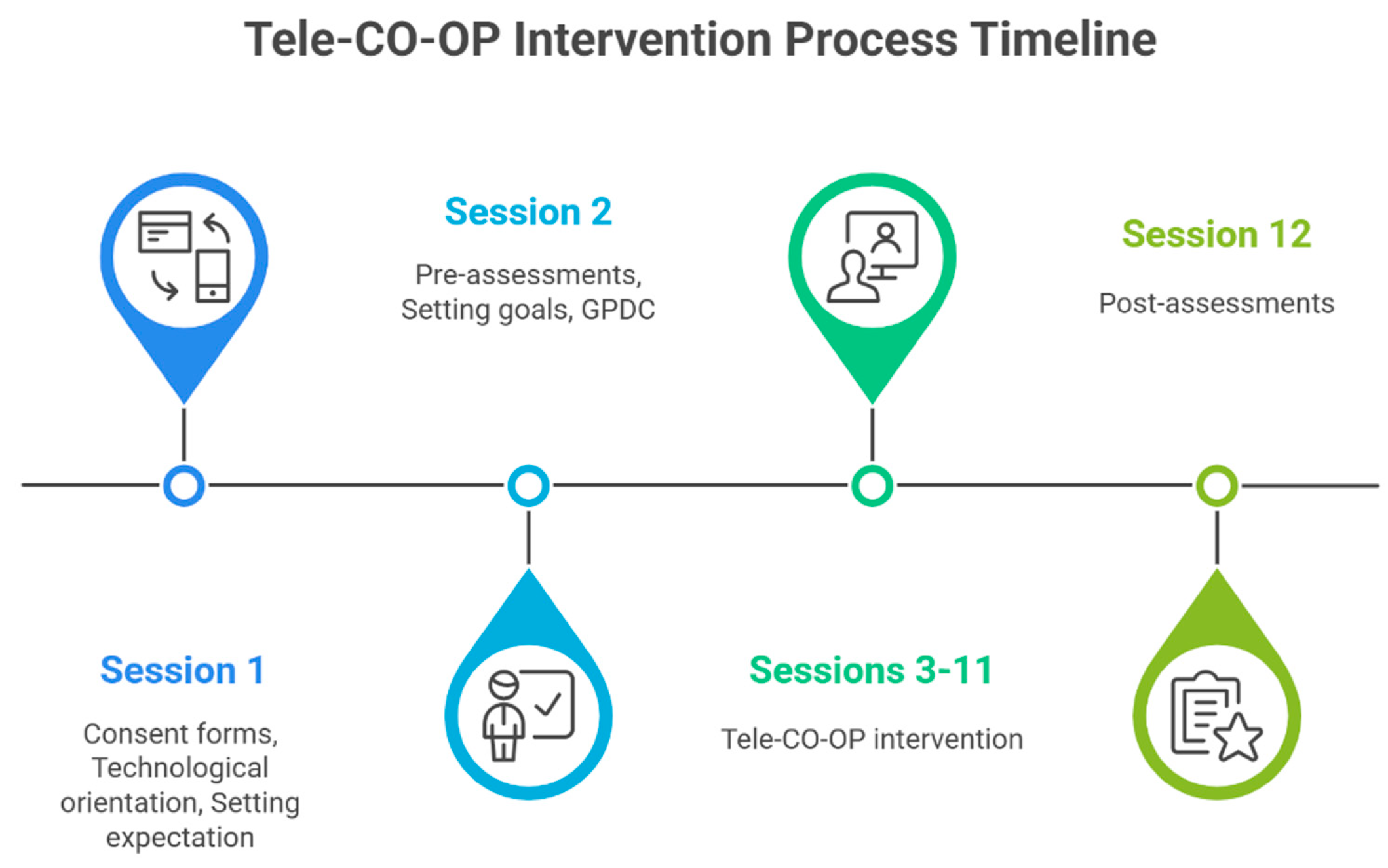

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Intervention

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility

3.2. Acceptability

3.3. Preliminary Efficacy

4. Discussion

4.1. Feasibility

4.2. Acceptability

4.3. Preliminary Efficacy

4.4. Limitations and Future Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Tele CO-OP Intervention Process

References

- Patel, D.R.; Merrick, J. Neurodevelopmental and neurobehavioral disorders. Transl. Pediatr. 2020, 9 (Suppl. S1), S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.S.; George, R.L.; Remya, V.R.; A, R.P.; Saji, C.V.; Mullasseril, R.R.; AShenoi, R.; Nair, J.; Krishna, R.; N, K.K.; et al. Prevalence Estimates of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (NDDs) in a South Indian Population. Ann. Neurosci. 2025, 09727531251348188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, R.; Gandhi, T.K. Functional connectivity dynamics show resting-state instability and rightward parietal dysfunction in ADHD. In Proceedings of the 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Sydney, Australia, 24–27 July 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.; Kakkar, S.; Singhal, R.; Negi, A. Neurodevelopmental Disabilities: Current Perspectives on Burden of Care and Stigma—A Comprehensive Review. In Health Psychology in Integrative Health Care; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2024; pp. 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Martínez, N.; Delgado-Lobete, L.; Montes-Montes, R.; Ruiz-Pérez, N.; Ruiz-Pérez, M.; Santos-del-Riego, S. Participation in everyday activities of children with and without neurodevelopmental disorders: A cross-sectional study in Spain. Children 2020, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Neurodevelopmental Disorders: DSM-5® Selections; American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Faraone, S.V.; Banaschewski, T.; Coghill, D.; Zheng, Y.; Biederman, J.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Newcorn, J.H.; Gignac, M.; Al Saud, N.M.; Manor, I.; et al. The world federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 789–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Child Development Services. Available online: https://www.health.gov.il/Subjects/KidsAndMatures/child_development/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 27 October 2025). (In Hebrew)

- Lucas, B.R.; Elliott, E.J.; Coggan, S.; Pinto, R.Z.; Jirikowic, T.; McCoy, S.W.; Latimer, J. Interventions to improve gross motor performance in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: A meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Honan, I. Effectiveness of pediatric occupational therapy for children with disabilities: A systematic review. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2019, 66, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits-Engelsman, B.; Vincon, S.; Blank, R.; Quadrado, V.H.; Polatajko, H.; Wilson, P.H. Evaluating the evidence for motor-based interventions in developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 74, 72–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polatajko, H.J. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP) approach. Perspect. Hum. Occup. Theor. Underlying Practice. Phila. FA Davis 2017, 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Polatajko, H.J.; Mandich, A.D.; Missiuna, C.; Miller, L.T.; Macnab, J.J.; Malloy-Miller, T.; Kinsella, E.A. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP) part III-the protocol in brief. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2001, 20, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, S.E.; Polatajko, H.J. Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance in Occupational Therapy: Using the CO-OP Approach to Enable Participation Across the Lifespan; Dawson, D.R., McEwen, S.E., Polatajko, H.J., Eds.; AOTA Press, The American Occupational Therapy Association, Incorporated: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2017; Available online: https://lccn.loc.gov/2017950778 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Madieu, E.; Gagné-Trudel, S.; Therriault, P.Y.; Cantin, N. Effectiveness of CO-OP approach for children with neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2023, 5, 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezinat, C.; Lebrault, H.; Câmara-Costa, H.; Martini, R.; Chevignard, M. Transfer of skills acquired through Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) approach in children with executive functions deficits following acquired brain injury. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2025, 72, e70040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C.R.S.; Cardoso, A.A.; Polatajko, H.J.; de Castro Magalhães, L. Efficacy of the Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) approach with and without parental coaching on activity and participation for children with developmental coordination disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 110, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiozu, H.; Kurasawa, S. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP) approach as telehealth for a child with developmental coordination disorder: A case report. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2023, 4, 1241981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapiets, S.J.; Hastings, R.P.; Stanford, C.; Totsika, V. Families’ access to early intervention and supports for children with developmental disabilities. J. Early Interv. 2023, 45, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, K.; Bican, R.; Boster, J.; Christensen, C.; Coffman, C.; Fallieras, K.; Long, R.; Mansfield, C.; O’Rourke, S.; Pauline, L.; et al. Feasibility and acceptability of clinical pediatric telerehabilitation services. Int. J. Telerehabilitation 2020, 12, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Telemedicine Association (ATA). American Telemedicine Association—ATA. Available online: https://www.americantelemed.org/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Boccalandro, E.A.; Dallari, G.; Mannucci, P.M. Telemedicine and telerehabilitation: Current and forthcoming applications in haemophilia. Blood Transfus. 2019, 17, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedeva, E.I.; Aleksandrova, O.A.; Kroshilin, S.V. Telemedicine in modern conditions: The attitude of society and the vector of development. Ekon. I Sotsialnye Peremeny 2022, 15, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretti, A.; Amenta, F.; Tayebati, S.K.; Nittari, G.; Mahdi, S.S. Telerehabilitation: Review of the state-of-the-art and areas of application. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2017, 4, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.R.; Barents, E.R.; Cole, A.G.; Klaver, A.L.; Van Kampen, K.; Webb, L.M.; Wolfer, K.A. Use and perceptions of telehealth by pediatric occupational therapists post COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods survey. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2025, 16, e6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suso-Martí, L.; La Touche, R.; Herranz-Gómez, A.; Angulo-Díaz-Parreño, S.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Cuenca-Martínez, F. Effectiveness of telerehabilitation in physical therapist practice: An umbrella and mapping review with meta–meta-Analysis. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Telehealth Guidelines in Occupational Therapy Practice; AOTA Press: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L.A.; Rasmussen, S.A. Potentials of telerehabilitation for families of children with special health care needs during the coronavirus disease 2019 emergency—Reply. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, P.; Gefen, N.; Weiss, P.L.; Beeri, M.; Landa, J.; Krasovsky, T. What does “tele” do to rehabilitation? Thematic analysis of therapists’ and families’ experiences of pediatric telerehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratte, G.; Couture, M.; Morin, M.; Berbari, J.; Tousignant, M.; Camden, C. Evaluation of a web platform aiming to support parents having a child with developmental coordination disorder: Brief report. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2020, 23, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almog, T.; Gilboa, Y. Remote delivery of service: A survey of occupational therapists’ perceptions. Rehabil. Process Outcome 2022, 11, 11795727221117503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsak, H.I. Telerehabilitation services: A successful paradigm for occupational therapy clinical services. Int. Phys. Med. Rehabil. J. 2020, 5, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhart, S.; Raz-Silbiger, S.; Beeri, M.; Gilboa, Y. Occupation Based Telerehabilitation Intervention for Adolescents with Myelomeningocele: A Pilot Study. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2020, 41, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeir, T.; Makranz, C.; Peretz, T.; Odem, E.; Tsabari, S.; Nahum, M.; Gilboa, Y. Cognitive Retraining and Functional Treatment (CRAFT) for adults with cancer related cognitive impairment: A preliminary efficacy study. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beit Yosef, A.; Jacobs, J.M.; Shames, J.; Schwartz, I.; Gilboa, Y. A performance-based teleintervention for adults in the chronic stage after acquired brain injury: An exploratory pilot randomized controlled crossover study. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, S.; Mirzakhany, N.; Dehghani, S.; Pashmdarfard, M. The use of tele-occupational therapy for children and adolescents with different disabilities: Systematic review of RCT articles. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2023, 37, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprandi, M.C.; Bardoni, A.; Corno, L.; Guerrini, A.M.; Molatore, L.; Negri, L.; Beretta, E.; Locatelli, F.; Strazzer, S.; Poggi, G. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Real-Time Telerehabilitation Intervention for Children and Young Adults with Acquired Brain Injury During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Experience Report. Int. J. Telerehabilitation 2021, 13, e6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschbrenner, K.A.; Kruse, G.; Gallo, J.J.; Plano Clark, V.L. Applying mixed methods to pilot feasibility studies to inform intervention trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2022, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Cognitive Approaches Network (ICAN). (n.d.). CO-OP: An Evidence-Based Approach. Available online: https://www.icancoop.org/pages/copy-of-co-op-an-evidence-based-approach (accessed on day month year).

- Hirsch, A.; Waldman-Levi, A.; Porush, S. Questionnaires to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention given to children in occupational therapy: Questionnaires for expectations and satisfaction of parents and questionnaires for a teacher. Isr. J. Occup. Ther. 2005, 14, H232–H235. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Law, M.; Baptiste, S.; Carswell, A.; McColl, M.A.; Polatajko, H.; Pollock, N. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, 5th ed.; CAOT Publications: Ottawa, Canada, 2017; Available online: https://www.thecopm.ca/learn/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Waldman-Levi, A.; Hirsch, I.; Gutwillig, G.; Parush, S. Psychometric properties of the Parents as Partners in Intervention (PAPI) Questionnaires. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 71, 7102220020p1–7102220020p8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, A.; McColl, M.A.; Baptiste, S.; Law, M.; Polatajko, H.; Pollock, N. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: A research and clinical literature review. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2004, 71, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM). The COPM is in Use. 2018. Available online: http://www.thecopm.ca/advanced/using-the-copm-with-children (accessed on day month year).

- Miller, L.; Polatajko, H.J.; Missiuna, C.; Mandich, A.D.; Macnab, J.J. A pilot trial of a cognitive treatment for children with developmental coordination disorder. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2001, 20, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, R.; Rios, J.; Polatajko, H.; Wolf, T.; McEwen, S. The performance quality rating scale (PQRS): Reliability, convergent validity, and internal responsiveness for two scoring systems. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Zagmis Rozen, D.; Amar, E.; Hershkowitz, F.; Gilboa, Y. Occupational therapists’ perspective on remote service after initial experience trail during the COVID-19 pandemic. Isr. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 30. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356459254_Occupational_Therapists’_Perspective_on_Remote_Service_after_Initial_Experience_Trail_During_the_COVID-19_Pandemic (accessed on 27 October 2025). (In Hebrew).

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camden, C.; Couture, M.; Pratte, G.; Morin, M.; Roberge, P.; Poder, T.; Maltais, D.B.; Jasmin, E.; Hurtubise, K.; Ducreux, E.; et al. Recruitment, use, and satisfaction with a web platform supporting families of children with suspected or diagnosed developmental coordination disorder: A randomized feasibility trial. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2019, 22, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frigerio, P.; Del Monte, L.; Sotgiu, A.; De Giacomo, C.; Vignoli, A. Parents’ satisfaction of tele-rehabilitation for children with neurodevelopmental disabilities during the Covid-19 Pandemic. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckingham, S.A.; Anil, K.; Demain, S.; Gunn, H.; Jones, R.B.; Kent, B.; Logan, A.; Marsden, J.; Playford, E.D.; Freeman, J. Telerehabilitation for people with physical disabilities and movement impairment: A survey of United Kingdom practitioners. JMIRx Med. 2022, 3, e30516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corey, T. Perspectives of Occupational Therapy Practitioners on Benefits and Barriers on Providing Occupational Therapy Services via Telehealth. Ph.D. Thesis, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Maghazil, A.M.; Qureshi, A.Z.; Tantawy, S.; Moukais, I.S.; Aldajani, A.A. Knowledge and attitudes of rehabilitation professional toward telerehabilitation in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional survey. Telemed. e-Health 2021, 27, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leochico, C.F.D.; Tyagi, N. Teleoccupational Therapy. In Telerehabilitation, E-Book: Principles and Practice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; p. 297. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Arberas, E.; Casais-Suarez, Y.; Fernandez-Mendez, A.; Menendez-Espina, S.; Rodriguez-Menendez, S.; Llosa, J.A.; Prieto-Saborit, J.A. Evidence-based implementation of the family-centered model and the use of tele-intervention in early childhood services: A systematic review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, D.C.C.; Rattner, M.; James, L.E.; García, J.F.B. Barriers and facilitators to implementing a community-based psychosocial support intervention conducted in-person and remotely: A qualitative study in Quibdó, Colombia. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2024, 12, e2300032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houtrow, A.; Murphy, N.; Council on Children with Disabilities. Prescribing physical, occupational, and speech therapy services for children with disabilities. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20190285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camden, C.; Silva, M. Pediatric telehealth: Opportunities created by the COVID-19 and suggestions to sustain its use to support families of children with disabilities. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2021, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.N.G.; Fong, K.N. Effects of telerehabilitation in occupational therapy practice: A systematic review. Hong Kong J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 32, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogourtsova, T.; Boychuck, Z.; O’Donnell, M.; Ahmed, S.; Osman, G.; Majnemer, A. Telerehabilitation for children and youth with developmental disabilities and their families: A systematic review. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2022, 43, 129–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capistran, J.; Martini, R. Exploring inter-task transfer following a CO-OP approach with four children with DCD: A single subject multiple baseline design. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2016, 49, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, C.R.S.; Cardoso, A.A.; Magalhães, L.D.C. Efficacy of the cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance with Brazilian children with developmental coordination disorder. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 26, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houldin, A.; McEwen, S.E.; Howell, M.W.; Polatajko, H.J. The cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance approach and transfer: A scoping review. Occup. Particip. Health 2018, 38, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierpont, R.; Berman, E.; Hildebrand, M. Increasing Generalization and Caregiver Self-Efficacy Through Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) Training. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7411520499p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, F.; Kennedy-Behr, A.; Ziviani, J. Occupational Performance Coaching: A Manual for Practitioners and Researchers; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gibaud-Wallston, J.; Wandersman, L.P. Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (PSOC); APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

| Goal | CO-OP Strategy Use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Organizing the required equipment for school according to the class schedule | Attention to doing | Therapist: How will you remember the required equipment for each day? Client: I will write the schedule on my board inside my room. |

| Task specification\modification | Therapist: Where should you place your books? Client: I can reach the lower shelf above the desk by myself. | |

| Verbal-motor mnemonic | Therapist: How can we call the required stages of this activity? Client: Take out, choose, put in and checking. | |

| Complete writing assignment independently | Body position | Therapist: (demonstrate sitting bent over and away from the table) What do you think about my sitting posture? Client: Your back will hurt. Therapist: What should I do? Client: Approach the table and straighten your back. |

| Task specification\modification | Therapist: Which place will allow you enough space to study with no other distractions? Client: My brother and my room, near the desk with my study equipment, while my brother is in the playroom. | |

| Verbal-motor mnemonic | Therapist: (displays a group of letters) What do all these letters have in common? Client: They are all written in the same direction. A balanced line from above and going straight down. Therapist: Great. What do you think will be a proper name for this group? Client: The ceiling and the wall. | |

| Eating a meal independently using a spoon without dropping the food | Attention to doing | Therapist: Demonstrate eating while standing and watching television. Client: You are spilling the food everywhere Therapist: I didn’t notice, what should I do differently? Client: Your mouth is very far from the plate. Maybe you should sit down and watch the food instead the TV. |

| Task specification\modification | An observation on mealtime was performed and recommendations were given by the occupational therapist, such as the following: replace the chair (higher one), and use a shorter spoon and a bowl instead of a flat plate. | |

| Verbal–rote script | Therapist: How can we remember the sequence of all the steps we need to do? Client: Sit, closer, pick a little, and directly into the mouth. |

| Characteristics | N (%) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 6.66 (6.04–7.81) | |

| Gender | ||

| Girls | 10 (71.43) | |

| Boys | 4 (28.57) | |

| Fathers | ||

| Age (years:months) | 38:6 (32–42) | |

| Education (years) | 15 (12–16) | |

| Mothers (years) | ||

| Age (years:months) | 39:6 (35–45) | |

| Education (years) | 16 (15–16) | |

| Number of children in the family | 3 (2.75–5.25) | |

| Native language | ||

| Hebrew | 10 (71.43) | |

| Bilingual | 4 (28.57) |

| PAPI-Q Statements | Parents M (SD) | Occupational Therapists M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Did the number of sessions match the child’s needs? | 4.38 (0.65) | 4.43 (0.51) |

| Did you feel like a partner in the process? | 4.54 (0.66) | 4.82 (0.40) |

| Did the child participate in most of the sessions? | 4.77 (0.60) | 4.64 (0.74) |

| Did you/the child and his parent practice at home according to the guidance? | 4 (0.58) | 3.69 (1.18) |

| In your opinion, did you/the parent acquire tools to implement with other difficulties? | 4 (1.00) | 3.89 (0.60) |

| General satisfaction with the therapeutic process. | 4.38 (0.77) | 3.71 (0.99) |

| Satisfaction with the topics the therapy dealt with. | 4.36 (0.46) | 4.08 (0.76) |

| Total | 4.34 (0.47) | 4.17 (0.53) |

| Measures | Pre Median (IQR) | Post Median (IQR) | Z | P | r (ES) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPM—performance | |||||

| Child (trained goals) | 5 (3.29–6.08) | 9 (8.1–9.75) | −3.279 | 0.001 | −0.881 |

| Child (untrained goals) a | 5 (4–6) | 8.5 (7.5–10) | −2.937 | 0.003 | −0.885 |

| Parent (trained goals) | 4.83 (3.83–5.67) | (7.17–8.69) | −3.062 | 0.002 | −0.818 |

| Parent (untrained goals) a | 6.5 (5.5–7) | 8.5 (6.5–9) | −2.392 | 0.017 | −0.721 |

| COPM—satisfaction | |||||

| Parent (trained goals) | 5 (3.08–5.81) | 9.17 (8.1–10) | −3.185 | 0.001 | −0.851 |

| Parent (untrained goals) a | 6.5 (4.5–6.5) | 9 (8–10) | −2.606 | 0.009 | −0.786 |

| PQRS (trained goals) | 4.58 (3.25–5.5) | 8 (7.67–8.54) | −3.298 | 0.001 | 0.881 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ben Zagmi-Averbuch, S.; Rozen, D.; Aharon-Felsen, B.; Siman Tov, R.; Lowengrub, J.; Tal-Saban, M.; Gilboa, Y. Occupation-Based Tele-Intervention for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Pilot Study. Children 2025, 12, 1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111521

Ben Zagmi-Averbuch S, Rozen D, Aharon-Felsen B, Siman Tov R, Lowengrub J, Tal-Saban M, Gilboa Y. Occupation-Based Tele-Intervention for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Pilot Study. Children. 2025; 12(11):1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111521

Chicago/Turabian StyleBen Zagmi-Averbuch, Stav, Deena Rozen, Bathia Aharon-Felsen, Revital Siman Tov, Jeffrey Lowengrub, Miri Tal-Saban, and Yafit Gilboa. 2025. "Occupation-Based Tele-Intervention for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Pilot Study" Children 12, no. 11: 1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111521

APA StyleBen Zagmi-Averbuch, S., Rozen, D., Aharon-Felsen, B., Siman Tov, R., Lowengrub, J., Tal-Saban, M., & Gilboa, Y. (2025). Occupation-Based Tele-Intervention for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Pilot Study. Children, 12(11), 1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111521