1. Introduction

The opioid epidemic has garnered growing concern (e.g., [

1,

2,

3]), particularly in child welfare systems in the United States of America. In fact, rates of opioid prescriptions, opioid misuse, and opioid-related overdose deaths have been on the rise since the 1990s [

4]. These increased rates prompted professionals in the United States of America to describe opioid use disorder as a public health emergency in 2017 [

5]. Given this constellation of opioid-related issues, understanding the pathways of risk for intergenerational cycles of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), insecure/disorganized attachment patterns between parents and their young children, and substance use in opioid-involved populations has become even more important, especially when planning for appropriate parenting and other interventions. Exposure to parents’ substance use itself is considered an ACE, with 25.6% of participants in the original ACEs Study endorsing that they had been exposed to a parent who was substance-involved [

6]. Further, parents’ substance use increases their risk of maltreating children, removal of children from their care, and failure to achieve reunification after a removal has occurred [

7,

8]. This increased risk is likely related to these parents’ greater parenting stress, decreased attentiveness and engagement, and harsher discipline. Thus, efforts meant to break intergenerational cycles and to prevent maladaptive outcomes for young children necessitate a lens that is both trauma-informed and attachment-focused [

9]. Consistently, the goal of this study was to examine potential pathways from ACEs to perceived insecure/disorganized attachment patterns in a sample of mothers and fathers who were opioid-involved.

When examining intergenerational cycles, attachment needs to be considered. Such consideration is particularly important in families with young children, as young children actively form attachments with caregivers. Of particular interest for this study, attachment theory has demonstrated the importance of young children establishing safe and secure internal working models from which they can view their world [

10]. Safe and secure internal working models, or mental maps of relationships, are formed when young children are cared for consistently and reliably by caregivers who are warm but firm. When internal working models are not safe and secure, young children (and individuals, in general) display heightened risk of insecure or even disorganized attachment, as well as later emotional regulation difficulties, poor coping skills, and relationship insecurity [

11]. ACEs (e.g., abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction), especially at the hands of primary attachment figures, can be highly detrimental to young children’s early internal safety representations [

12]. Understanding pathways to insecure/disorganized attachment patterns is important because childhood adversity is far from uncommon and because the majority of children who were maltreated were perpetrated against by a parent [

6].

Much of the literature has considered direct consequences stemming from childhood adversity and other ACEs. Infants are predisposed biologically to attach to their caregivers, as caregivers protect [

13], foster learning of regulation, and shape brain development via early interaction [

14]. Thus, the connection between childhood adversity and insecure attachment is salient. Childhood adversity has been related consistently to insecure attachment for caregivers during their own childhoods [

12] and for parents’ own young children during their parenting [

15,

16]. Further, childhood adversity is related to maladaptive coping mechanisms (e.g., substance use) [

6,

17] and to psychological sequelae (e.g., depression and trauma symptoms) [

18]. Rather than being independent, these parental risk factors tend to coexist [

19], with these factors being possible mechanisms of connection between ACEs and perceived insecure/disorganized attachment patterns. Further, these factors need to be considered in the context of life stressors [

20].

In fact, research has suggested a significant intergenerational component to childhood adversity [

21,

22], substance use [

23], and attachment [

12]. Retrospective and prospective data indicate that these variables increase individuals’ risk of maltreating their own children, using substances themselves, and fostering insecure attachment with their own children. Less is known, however, regarding why such intergenerational cycles continue to repeat, as few studies have investigated the overlapping predictive and indirect relationships needed to understand parent–young child attachment [

24]. Thus, this study examined both direct and indirect pathways among ACEs, perceived insecure/disorganized attachment patterns, and psychological sequelae. As such intergenerational cycles have been examined less in fathers than mothers [

25], attempts were made to include both mothers and fathers in this study. Overall, it is vital to identify ports of entry for breaking these cycles so that young children do not have to endure the same issues as previous generations.

The Present Study

Although childhood adversity and other ACEs have been examined widely, the variables noted above have yet to be examined collectively in an interactional model for parents who are opioid-involved (to the authors’ knowledge). Moreover, research has called for further study of the mechanisms by which ACEs and parent–young child attachment patterns may be related [

24,

26]. These relationships are particularly important for parents who are substance-involved and who consequently exhibit a higher risk of maladaptive parenting and insecure/disorganized attachment [

7]. To date, research on parenting, attachment, and parents’ substance use has largely addressed the relationship between young children and their mothers [

27], to the exclusion of fathers. Even with increasing rates of opioid misuse in the United States of America [

28], especially in males [

29], only one review of opioid use in fathers exists [

1] to the authors’ knowledge.

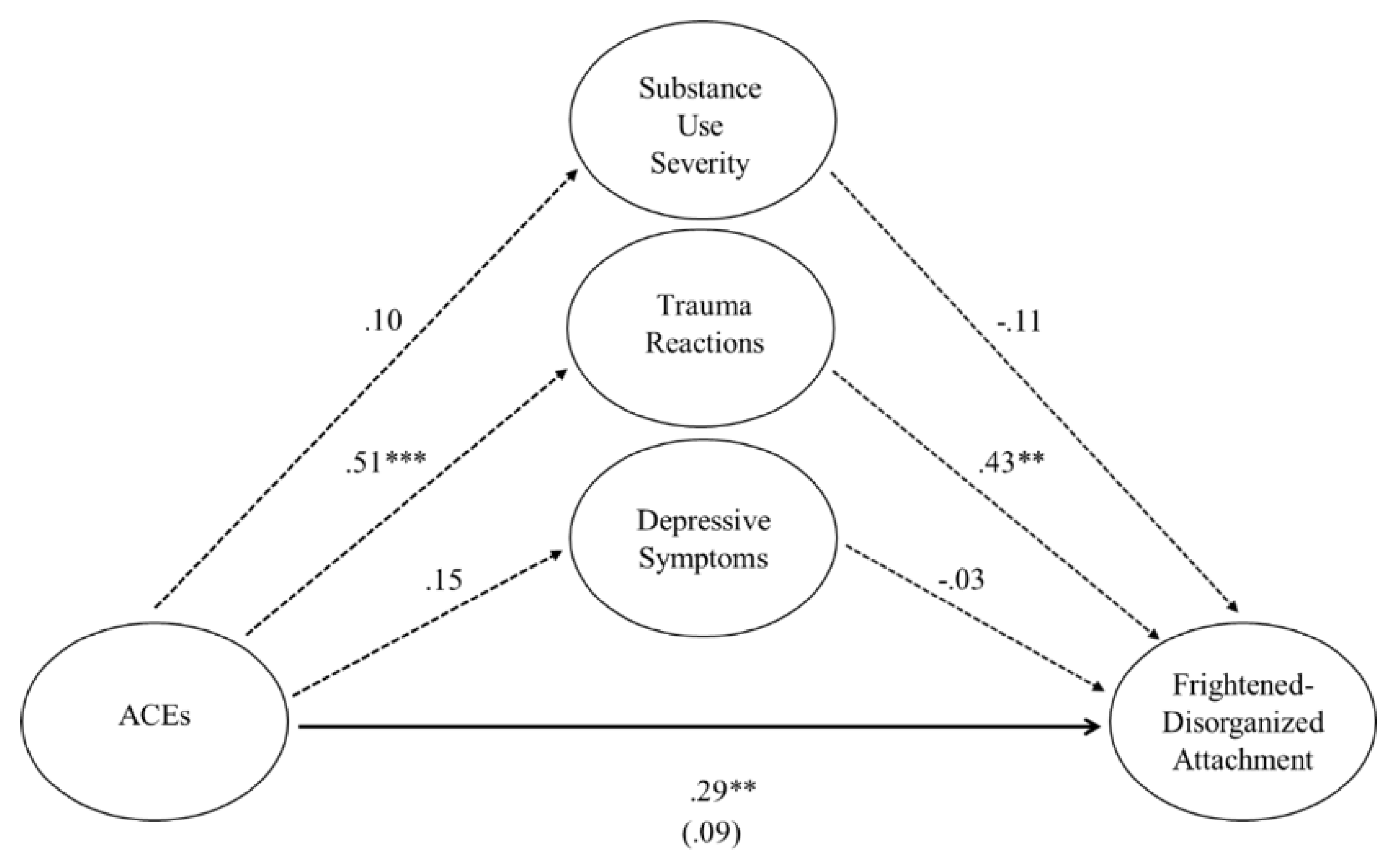

To address these gaps in the literature, this study examined mediating factors that may be driving the relationships between parents’ ACEs and their perceptions of parent–young child insecure/disorganized attachment patterns. This study recruited a sample of mothers and fathers who were opioid-involved to examine the direct and indirect relationships between their ACEs and parent–young child attachment patterns using the parents’ substance use severity, depression, and trauma symptoms as mediators in a PROCESS mediational model [

30]. It was expected that mothers and fathers’ ACEs would predict their respective ratings of insecure/disorganized attachment patterns with their young children and that substance use severity, depression, and trauma symptoms would serve as mediators in this relationship. It was hoped that information gained from this study would help to better inform parenting programs in facilitating secure attachment between mothers and fathers with their young children when substances are involved.

4. Conclusions

The objective of this study was to uncover pathways of risk that may perpetuate intergenerational cycles between ACEs and insecure/disorganized attachment patterns in mothers and fathers who are opioid-involved. Historically, much of the literature has considered sequelae stemming from early adversity, including, but not limited to, insecure attachment patterns, lifetime substance use, psychological sequela (e.g., depression and trauma symptoms), and negative parenting [

6,

12,

15,

18]. These various risk factors are likely to overlap [

6,

19,

42] and, thus, may be best understood through examination of indirect predictive relationships [

24] and collective models that bring these variables together. Given increased concern from the opioid epidemic [

3] and evidence that parents who are opioid-involved may demonstrate heightened parenting difficulties [

1], this study sought to expand on existing research while also filling gaps in the literature.

Of particular interest, research has focused overwhelmingly on mothers, with fathers seldom being included in empirical discussions of trauma, attachment, and/or parenting [

1,

25]. Cassidy and colleagues [

43] posited that this discrepancy reflected likely challenges in recruiting fathers for research. The challenges of recruiting fathers were compounded in this study by fathers being more likely to be employed than mothers (thereby making them less likely to participate due to work obligations) and by unprecedented difficulties brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, this study was still successful in expanding efforts to examine mothers

and fathers and to explain pathways of risk between parents’ ACEs and insecure/disorganized attachment patterns.

Mediational models examined predictive pathways from mothers and fathers’ ACEs to insecure/disorganized attachment patterns with their young children, with substance use severity, depression, and trauma symptoms as potential mediators. First, the hypothesized path from parents’ ACEs to insecure/disorganized attachment patterns (i.e., direct effect) was supported for mother–young child disorganized attachments

only, such that mothers with higher ACEs perceived greater frightened–disorganized and helpless–disorganized attachment with their young children. In other words, mothers’ ACEs did not predict mother–young child insecure attachment patterns, only mother–young child disorganized attachment patterns. These findings demonstrated that mothers’ childhood adversity may be related to disorganized attachment patterns in particular, rather than to other insecure attachment patterns in general [

44].

The hypothesized pathways (i.e., direct effects) from fathers’ ACEs to father–young child insecure/disorganized attachment patterns were

unsupported for fathers’ perceptions of all four patterns of attachment. This lack of predictive relationships impeded the ability to learn more regarding the relationship between fathers’ ACEs and father–young child attachment patterns. Despite similarities in our mother and father samples on ACEs, the data highlighted that fathers endorsed higher levels of avoidant attachment patterns than did mothers. No other significant differences were noted in attachment patterns between mothers and fathers. Overall, these findings may imply that mothers and fathers’ perceptions of avoidant attachment patterns may represent different constructs, that mothers’ pathways may be different than those of fathers, and that attachment findings for mothers may not be generalizable to fathers [

43]. The sample size for fathers also may have played a role, as more fathers could not be recruited due to their employment responsibilities and the implementation of COVID-19 quarantine protocols in the United States of America during the course of this study. The role of fathers’ attachment consequently necessitates further study [

27,

43], especially since further exploration of fathers’ indirect mediational pathways could not be completed theoretically in this study.

Contrary to the hypotheses and previous findings [

6,

7], mothers’ ACEs did not predict their substance use severity, suggesting that a mediational role of substance use severity was not supported. Several theories should be considered in explaining these findings. In this study’s sample, 38% of mothers described prescription opioids (alone or alongside heroin) as their ‘drug of choice’, whereas 50% of mothers described heroin alone as their ‘drug of choice.’ (Opposite percentages were noted for fathers, perhaps explaining some of the differences in findings between mothers and fathers.) Nonetheless, it should be considered that the parents in this sample were receiving medication-assisted treatment at study recruitment. Individuals’ journeys with substance use recovery often vacillate between periods of stability (i.e., sobriety and adherence to treatment) and relapse [

27]. It is possible, therefore, that progress in substance treatment and stage of recovery may have buffering effects for mothers’ substance use severity on parent–young child attachment patterns.

In examining the mediational role of mothers’ depression, the hypothesis of this study was not supported. In contrast with this study’s expectations and with previous findings [

19,

45], mothers’ ACEs did not predict their depression. Interestingly, the majority of mothers (and fathers) in this study exhibited low levels of depression overall, with only 7% of mothers (and 11% of fathers) endorsing severe symptoms. Thus, it may be that this study’s sample was benefiting from the substance use and other treatments that they were receiving. In partial support of hypotheses, mothers’ depression predicted helpless–disorganized attachment. It may be that the helplessness associated with depression also presents itself in the mothering role and interferes with mothers’ abilities to identify young children’s emotional cues and to respond adaptively to them [

46]. These data were salient given that disorganized attachment patterns have been associated with the most maladaptive outcomes for young children [

47].

When examining the mediational role of mothers’ trauma symptoms, the hypotheses were found to be supported fully. Consistent with previous findings [

42], mothers’ ACEs predicted their trauma symptoms, which predicted both frightened–disorganized and helpless–disorganized attachment patterns. When examined collectively, mothers’ ACEs no longer predicted frightened–disorganized attachment patterns. Mothers’ trauma, however, mediated and explained 23% of the variance in the relationship between mothers’ ACEs and frightened–disorganized attachment patterns, representing a large indirect effect as a mechanism of action.

Next, variables were examined collectively in the prediction of helpless–disorganized attachment patterns. In contrast to results for frightened–disorganized attachment patterns, mothers’ ACEs and trauma symptoms no longer predicted helpless–disorganized attachment patterns. Mothers’ depression symptoms emerged as a significant predictor of helpless–disorganized attachment patterns (over and above mothers’ ACEs) and helped to explain 23% of the variance in helpless–disorganized attachment patterns. Bootstrapping procedures, however, were unable to conclude with 95% confidence that mothers’ depression represented a significant indirect effect. Thus, mothers’ depression predicted uniquely helpless–disorganized attachment patterns but did not significantly mediate the relationship between mothers’ ACEs and parent–young child helpless–disorganized attachment patterns.

These data suggested that, rather than mothers’ ACEs being

directly harmful for mother–young child attachment patterns, the long-term psychological consequences of mothers’ ACEs may carry a greater risk of perceived attachment patterns with their young children. Specifically, mothers’ trauma symptoms acted as a mechanism of action in the relationship between mothers’ ACEs and frightened–disorganized attachment patterns, whereas mothers’ depression predicted uniquely helpless–disorganized attachment patterns above and beyond mothers’ ACEs. These findings corroborated prior research suggesting that mothers’ current psychological symptoms, rather than their histories of childhood adversity, posed the greatest risk to establishing secure bonds with their young children [

42]. Disorganized attachment patterns may be exacerbated by the instability and inconsistency characteristic of the opioid recovery process [

27]. These findings stressed how mothers’ trauma and depression symptoms, along with their substance involvement, are threats to their young children’s sense of safety and security [

48].

The results of this study demonstrated the importance of interventions to be trauma-informed and family-focused when targeting difficulties with parents’ substance use, psychological sequelae, and parent–young child attachment patterns. To date, only one review seemed to comprehensively examine the literature on parenting and opioid use, and fathers who were opioid-involved had been studied seemingly only

once empirically [

1]. Unquestionably, it is vital that future work continues to investigate the specific difficulties and needs exhibited by mothers

and fathers who have high ACEs and who are opioid-involved to inform evidence-based practice. Future work should utilize a family systems approach to best understand the development of insecure/disorganized attachment patterns between parents and their young children [

49]. See Renk and colleagues [

50] for a review of evidence-based treatments for parents who are substance-involved. Interventions such as Circle of Security [

51], which promote reflection on parents’ own childhood adversity and their current parenting, as well as reflective relationship-based treatments, such as Child–Parent Psychotherapy [

52], may also be helpful in mitigating risk for families with young children. Addressing parents’ psychological sequelae through evidence-based intervention approaches may provide further mitigation toward preserving the parenting capacities of mothers and fathers.

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. This study had a relatively homogenous sample, with demographic characteristics potentially compromising external validity. Although lacking in racial diversity, this mostly White/Caucasian sample reflected both the national demographic of opioid users [

53] and the racial disparities in those who receive prescription opioids [

54] in the United States of America. It should also be noted that this study examined mediations using a cross-sectional design, where ratings of all variables were collected within one time period. Although ACEs were likely to have occurred prior to the other variables of interest (given the nature of this construct), it cannot be determined with certainty whether parents’ depression or trauma symptoms preceded their development of insecure/disorganized attachment patterns with their young children. Further, cross-sectional data do not allow causal claims to be made.

Certainly, a greater sub-sample of fathers would have been optimal. Our efforts resulted in the recruitment of 26 fathers, an ostensibly small sample as compared to the sample of mothers. This sample size was complicated by the fact that fathers more often had to leave for work (relative to mothers) after receiving their medication-assisted treatment, as well as by restrictions put in place for COVID-19. This sample size of fathers was found to exceed that found in previous studies, however [

55]. The problematic omission of fathers in attachment research has long been documented [

49]. Even after a significant push for more research on father–child attachment, only 16 studies existed on this topic by 2019 [

56]. Moreover, only one review could be identified as examining fathers’ opioid use to date [

1]. Thus, this study still enhanced the literature on fathers.

This study utilized self-report measures to examine the variables of interest. Although several of the measures included validity scales, the possibility remains that parents may have exhibited positive or negative self-bias [

57] in their responses. Nonetheless, there were significant relationships among the variables of interest in this study. Further, Cassidy and colleagues [

43] stated the importance of conducting such intergenerational attachment research using self-report measures. It should be noted that, rather than the accuracy of attachment patterns (e.g., on the Strange Situation procedure), this study was interested in mothers and fathers’ perceptions of their attachment patterns with their young children. Nonetheless, future studies would benefit from including young children themselves, especially in conjunction with parent–young child observational paradigms.

In summary, this study uniquely added to the understanding of intergenerational risk pathways between parents’ ACEs and insecure/disorganized attachment patterns with parents who are opioid-involved. The results of this study suggested that mothers’ trauma and depression symptoms play a central role in perpetuating relationships between childhood adversity and disorganized attachment patterns with their young children. As such, these are essential targets for intervention with these mothers. Interestingly, fathers’ ACEs were not predictive of their attachment patterns with their young children. This study recognized that a low sample size of fathers relative to mothers may have impacted relationships among the variables investigated. Further inclusion of fathers in parenting, attachment, and trauma research is vital. Overall, these data highlighted that differences may exist in how mothers and fathers perceive parent–young child attachment patterns. These results have implications for tailoring trauma-informed and attachment-focused parenting interventions to help parents break perpetuating cycles of ACEs and insecure/disorganized attachment patterns.