1. Introduction

Parental stress refers to the psychological reaction that parents may experience when attempting to fulfil their caregiving and educational responsibilities. It is generally perceived as a negative or aversive response to the demands and expectations of parenting, especially when these are not met [

1,

2]. Parental stress relating to child-raising is very common [

3,

4]. It is estimated that between 36% and 50% of parents experience some level of concern or stress relating to their children’s behaviour, health, and development [

4,

5]. Sometimes, this requires professional counselling and support [

5]. There is consistent evidence of an association between parental stress and various issues affecting parents, children, and families. These issues include parental mental health and psychological well-being; emotional and behavioural problems in children; academic under-achievement; and inappropriate parenting behaviours, such as child abuse, marital problems, and family dysfunction [

6].

According to the general stress model proposed by Lazarus and Folkman [

7], stress results from an interaction between stressors, cognitive assessment of competency, and coping responses. Based on classic works by Selye [

8,

9,

10,

11], among others, we can also assume that stress is the sum of all factors. Parental stress differs conceptually from other types of stress experienced by parents (known as life stress), such as stress related to work, financial problems, and negative life events. However, the presence of other life stressors can exacerbate parental stress.

In their systematic review, Fang et al. [

12] found no correlation between parental stress and either the mother’s age or the child’s gender. However, they observed relationships with maternal depression, general child-related problems, social support, and parents’ educational level. The level of parental stress fluctuates depending on the stage of child development [

13,

14]. Conversely, it has been hypothesised that stressors are multidimensional regarding both their source and their type [

15]. This characteristic makes it challenging to develop explanatory theoretical models that facilitate forecasting. Traditionally, models are built on the principle of factor orthogonality. However, in the case of stress in general, and parental stress in particular, factors interact with each other (because they are interdependent) [

16,

17]. Abidin [

18] developed a model of parent–child relationships to explain parental stress. This model is composed mainly of two broad dimensions: the characteristics (or domain) of children and the characteristics (or domain) of parents.

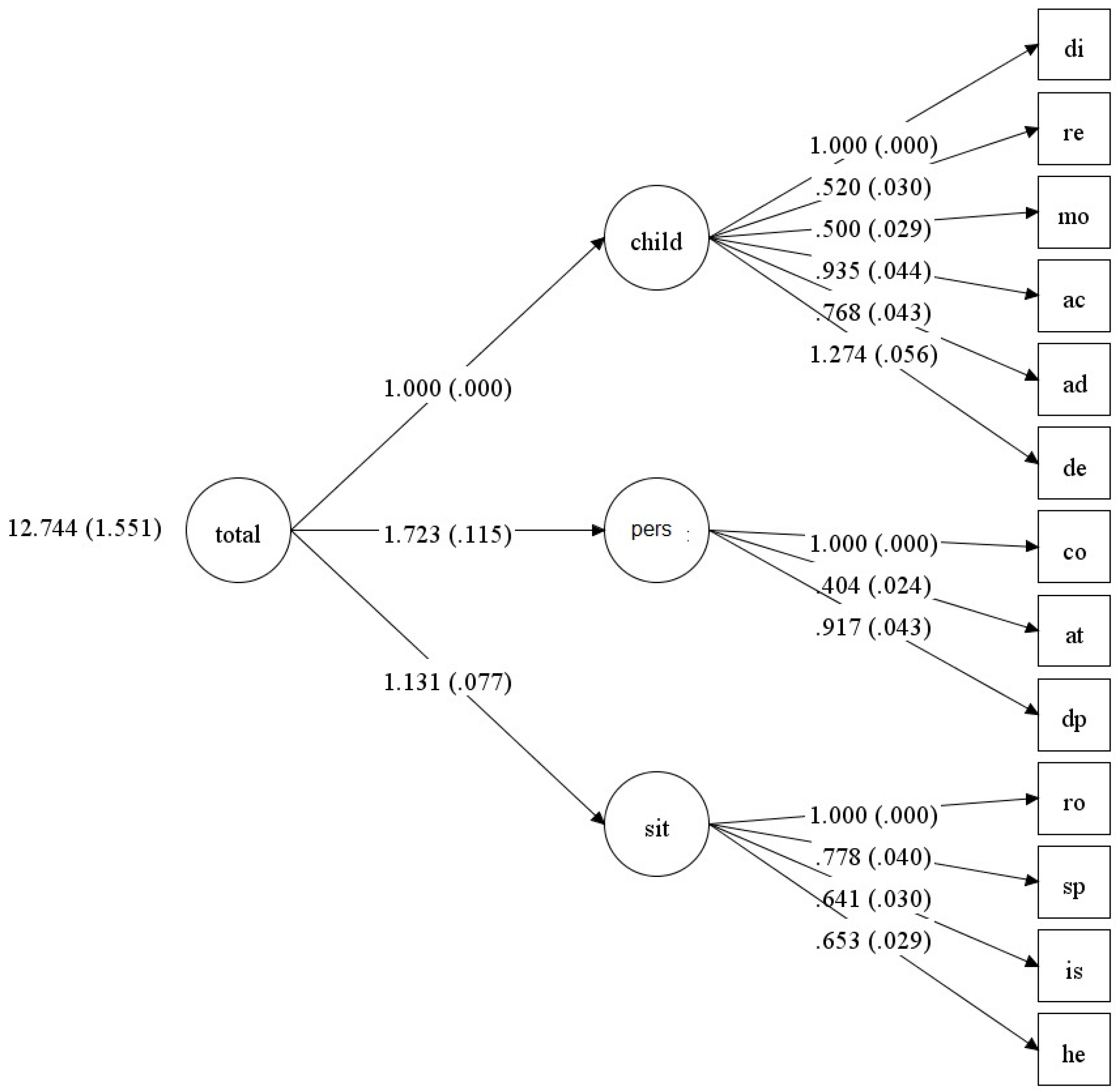

Fang et al. [

12] introduced a new interpretation of Abidin’s model, in which factors associated with total parental stress are organised into three domains: parents, children, and situation. The Parent Domain encompasses personality and functional aspects, including depression, attachment, and feelings of competence. The Child Domain refers to temperament and behaviour, while the situational domain includes social support, isolation, role restriction, and marital relationships.

Figure 1 shows the model proposed by Fang et al. [

12], which is a reorganisation of the variables proposed by Abidin. As can be seen in the figure, total parental stress is made up of three components: Child Factors, the parent’s Personal Factors, and Situational Factors. Please note that this reorganisation divides Abidin’s original parental dimension into two factors: personal and situational. Additionally, the inter-relationship of these three dimensions is indicated by discontinuous lines, showing that they can modulate the importance of their components beyond the accumulation of factors. For example, a parent’s feelings of competence (CO) are generated and reinforced by positive feedback from the child’s development (RE). Similarly, parental attachment (AT) can be generated and reinforced by any of the child’s characteristics, or even by the child’s own attachment to their parents; these inter-relationships make it challenging to develop an explanatory model of parental stress. This model served as the basis for the development of the Parental Stress Index (PSI) by Abidin [

19].

Although several scales are used to assess parental stress, the PSI is the oldest and most frequently used [

6,

20,

21]. It has been used since the first version was developed by Abidin [

19] and is currently in its fourth edition [

22].

Since the first version of the PSI was published, several studies have shown good internal consistency and adequate test–retest reliability. As it has evolved, different versions have been translated and administered in various countries and validated in different cultural groups, including France [

23], Portugal [

24], Canada [

25], Finland [

26], the Netherlands [

27], and China [

28,

29].

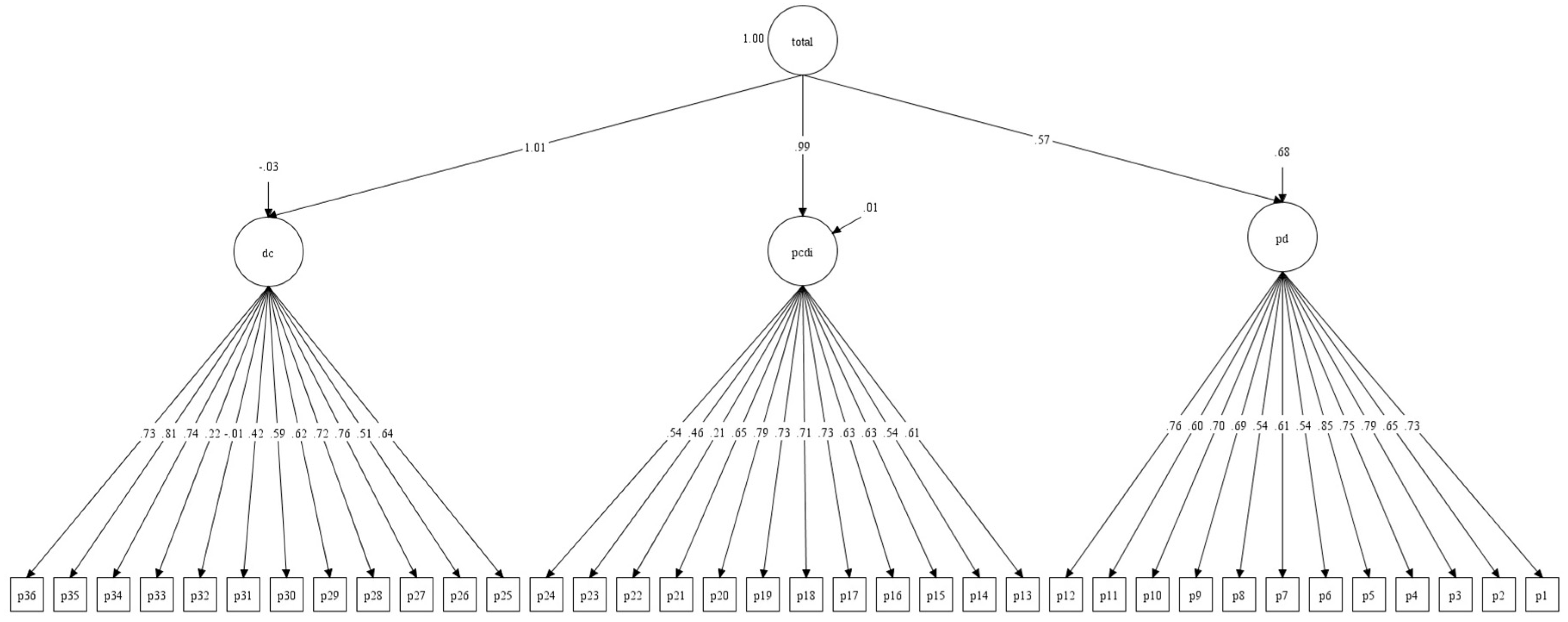

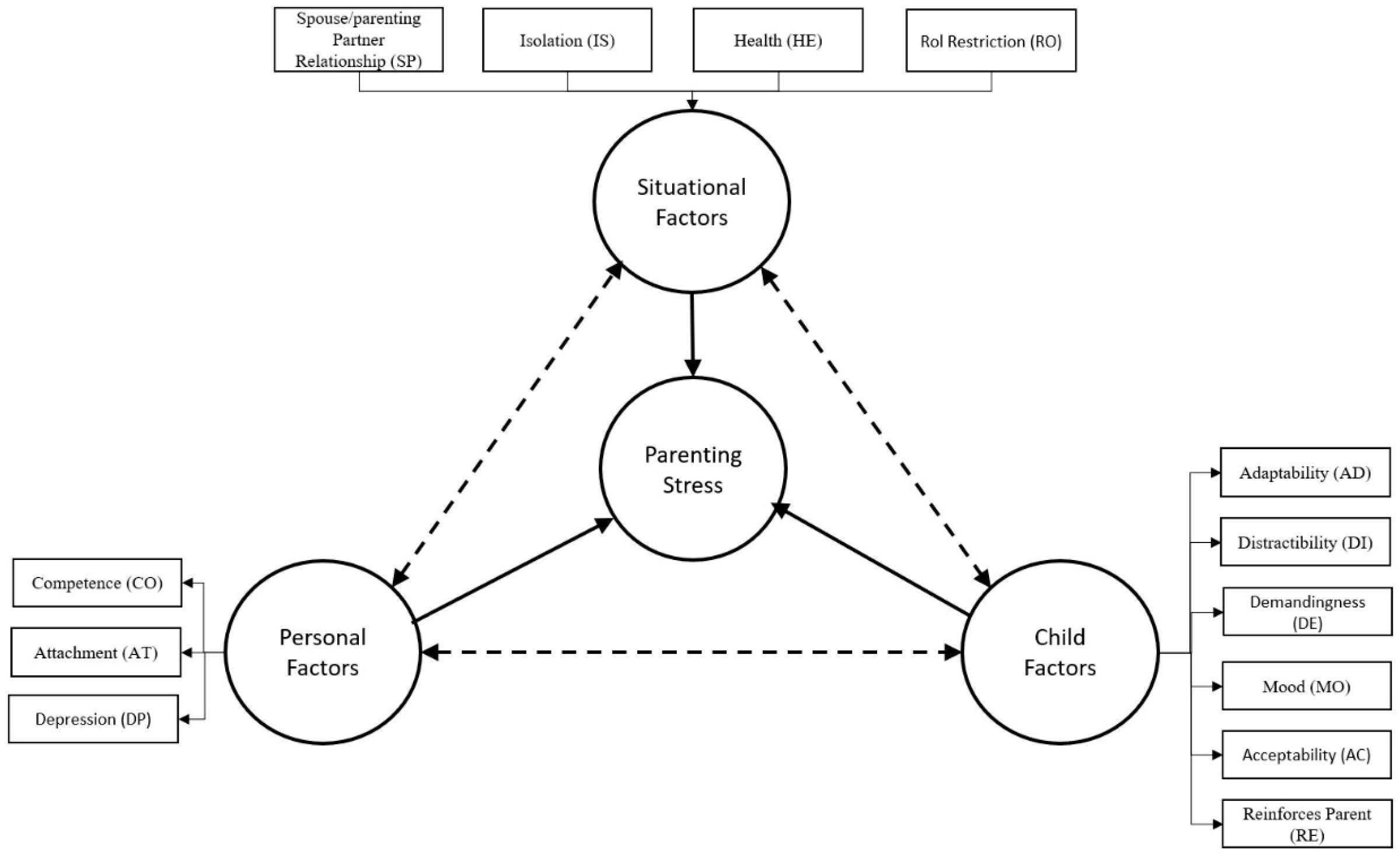

The original PSI consists of 101 items, divided into 13 factors organised into two domains: parents and children. In response to demand from researchers and clinicians, and following various factorial studies [

30], an abbreviated version (PSI-SF) was published. This focuses on the key element of the parent–child system, simplifying the structure into three domains: Parental Distress (PD), Parent–Child Dysfunctional Interaction (P-CDI) and Difficult Child (DC). The number of items in each domain is balanced, totalling 36 items.

A substantial body of literature has been compiled, providing ongoing evidence of its clinical usefulness and sound psychometric properties [

6,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. However, most validation studies have only focused on the short version, which limits the development of research [

20].

Several changes have been made to the wording of the items in the current version (PSI-4) to reflect new family and parenting styles, including single-parent families, same-sex families, and heterosexual families. There has also been a significant change to the instructions section. For example, it explains that the assessment is made in relation to a specific child, rather than to parenting situations in general; this allows us to capture information about the parental stress generated by raising each child, rather than providing a general index of parental stress. There are two versions of the PSI-4: PSI-4 LF—an evolution of the original Parental Stress Index [

39]—and PSI-4 SF. The PSI-4 LF includes 13 subscales (6 in the child subscales and 7 in the parent subscales) in two domains (Parent and Child domains). The short version (PSI-4 SF), derived from the previous one [

30], consists of 36 items organised around three dimensions (Parent Domain, Child Domain, and Dysfunctional Parent–Child Interaction). The PSI-4 SF is a valid instrument for detecting parenting dysfunctions, while the PSI-4 LF can help to formulate hypotheses about parenting and, thereby, design an intervention programmed. In addition, the PSI-4 can monitor the effects of the intervention. The aim of this study is to analyse the psychometric characteristics of the Spanish version of the PSI-4 in its two versions.

4. Discussion

Evidence from the specialised literature suggests that the construct evaluated (parental stress) is an important factor in the psychological health and well-being of parents, children, and the family as a whole [

18,

79,

80]. Parental stress often emerges at various stages during child-rearing and sometimes remains at high levels for prolonged periods. To plan possible interventions from the psychologist’s or paediatrician’s office, it is necessary to have screening and assessment tools translated into various languages and adapted to the cultural context of each country. The differences in mean scores between the Spanish and American samples alone justify the need for adaptation, demonstrating how culture can influence the evaluation of parenting behaviours and customs. The PSI is the international standard for assessing parental stress; however, its psychometric performance in non-clinical Spanish samples remains unknown. Although there are Spanish versions of the PSI-4, particularly the abbreviated form for research purposes, to date, there has been no official version with specific norms tailored to the Spanish population and its cultural context. The aim of this study was to address this issue.

Comparing the average scores obtained in our study with those in Abidin’s original study [

22] requires the development of specific norms for the Spanish population. Furthermore, differences in average parental stress scores according to children’s age necessitate the presentation of different norms [

13,

14]. No differences were found according to the child’s gender, and the available data do not allow us to analyse differences between fathers and mothers or parents’ partners.

The Spanish version of the PSI-4 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, similar to those of the original version or those obtained in other studies, indicating its suitability for measuring parental stress in a valid and reliable manner across cultures. The internal consistency indices can be considered excellent and even too high (above 0.90). This suggests that there may be some redundant items, and as a result, the scale may be longer than necessary [

81]. These data justify the demand for a shorter form from clinicians and researchers. However, the long form provides relevant clinical information for planning an intervention, if necessary.

We understand that high parental stress scores can remain stable over time in the absence of intervention. Although the group of parents who participated in the retest in our study was small, high stability was observed in the total score, both in the short and long forms. In this sense, our study provides valuable information rarely found in other studies. The review by Holly et al. [

6] highlights this gap in published psychometric studies.

Construct validity cannot be determined by a single analysis. Two approaches have been adopted to determine this: convergent validity, which utilises other measures of the same construct or other constructs theoretically consistent with the measure used, and discriminant validity, which is the ability of the measure to differentiate between groups with clinical symptoms and other groups. Specifically, the PSI-4 in all its forms and subscales has been found to correlate with the PSS score. The present study also demonstrates a correlation with a measure of stress and, to a lesser extent, with general anxiety and depression, measured using the DASS-21. The PSI-4 subscales show a high degree of correlation with PBI scores. Regarding discriminatory power, positive results have been obtained when comparing groups of parents of typically developing children with those parents whose children have a developmental disorder requiring intervention.

Studies reviewing the content validity of the PSI have yielded positive findings [

6,

20]. The items comprising the PSI were selected from the literature on child development, parent–child interaction, parenting practices, and child psychopathology. This aspect has been improved through the pilot test and subsequent versions of the PSI. However, the factorial structure of the PSI has been the subject of numerous studies [

22], particularly those involving translated and adapted versions in other languages. Notable among these are the adaptations into Turkish and Portuguese for the Brazilian population.

In the Turkish adaptation of the instrument [

82], a CFA was used to verify the scale structure following the methodology used by the PSI author; the structure was validated by two confirmatory factor analyses on a sample of 386 parents, one for the Child Domain (CD) and another for the Parent Domain (PD). The results of the CFI and TLI fit indices were below the cut-off point used in our study; however, they accepted that the structure of each domain was consistent with the author’s model.

In the validation of the Portuguese version in Brazil [

36], a different technique was used. Factor analysis (principal components, with varimax rotation) was performed on the scores of the thirteen subdomains obtained from a sample of 53 mothers of preterm infants, yielding a bifactorial structure that explained 64.57% of the variance. As this analysis is exploratory in nature, no measures of fit are available. However, the authors interpret the results as those of the two original domains (CD and PD), although they report that in the Child Domain, subscales such as Competence (CO) and Depression (DP) are also significantly saturated.

In essence, the PSI was constructed according to the philosophy of a construct composed of several independent subconstructs. However, the reality is not, in fact, orthogonal. A close examination of the components that constitute CD and PD reveals a clear obliquity between them. This obliquity is further accentuated when the items within each subscale are analysed.

On the other hand, in addition to the cultural differences that may exist in the way parental relationships are understood, there have been social and cultural changes in the last 20 years since the original PSI-4 version was published. We can justify the existence of certain differences in the factor structure of the theoretical model proposed by Abidin, the one obtained empirically in the PSI-4 typing studies, and the current ones. However, given the clinical significance of the PSI-4 subscales, we propose maintaining the same structure to facilitate comparisons in cross-cultural and cross-population studies.

The aim of the present work was to study the fourth version, both in its long and short forms—given the interest in having a version with fewer items—and with a normative population. The short form can be used for screening or in clinical contexts, while the long form can be used to obtain broader and deeper information when needed.

It is important to note that most of the studies cited used clinical samples composed of parents at risk, whereas our study was conducted with parents of children without known developmental disorders. This difference may be significant when analysing latent variables in a factor analysis. Nevertheless, the two-factor model, built on the subscale scores, is reproduced in the same way, improving the fit with respect to a three-factor model where the Parent Domain is subdivided into two factors (personal and situational). In the short form version, the fit to the original three-factor model is more adequate; perhaps this is one of the reasons, along with its ease of interpretation and application, that the short form is much more widely used than the long form. In our opinion, both forms are complementary: the PSI-4 SF can be used as a screening tool, and in cases where high scores are observed in any of the three factors (especially in the P-CDI factor), obtaining the complete PSI-4 profile can help us better plan a possible intervention. Furthermore, it is clinically useful, as research has shown that parental stress is higher in parents of children with a clinical diagnosis, as reported in this study. Parental stress can be related to poorer treatment outcomes, reducing their effectiveness due to lack of adherence and a decrease in the quantity and quality of interactions with children in daily activities. Parental stress monitoring allows clinicians to adjust treatment and identify risks for its continuation; therefore, the instrument must be sensitive to changes in parental stress throughout treatment.

5. Conclusions

The Spanish version of the PSI-4, in its two forms (LF and SF), demonstrated good psychometric qualities, indicating that it is capable of reliably and validly measuring parental stress in the Spanish population. The differences between the mean scores of the American and Spanish samples indicate the need to generate differential scoring norms.

The internal consistency of the PSI-4 in both versions is very acceptable, as is its test–retest stability. Regarding convergent validity and ability to differentiate between clinical groups, the PSI-4 is a tool that can be used for clinical purposes (screening and diagnosis) and to monitor treatment follow-up. Convergent validity with other consistent constructs indicates that the Spanish version of the PSI-4 assesses the construct of parental stress. Furthermore, a comparison between parents with typically developing children and those with children who require support or intervention demonstrates discriminative ability.

Clearly, further research is required to develop a theoretical model that incorporates mediating relationships between its components.

5.1. Limitations

Given the sample structure (characterised by a low proportion of fathers) and the medium to high educational level of the respondents, it is possible that the diversity of family structures in Spain is not fully represented. The need for respondents to have a good level of reading comprehension should be taken into account.

Furthermore, the relatively small size of the subsamples used to determine convergent validity and test–retest reliability could affect the value of the correlations, overestimating them. The convergent validity analysis was based solely on a subsample of 87 parents, resulting in a small sample size for test–retest reliability, which could lead to overestimating the stability of the correlations.

The timing of the application (weeks before the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic) and the pause from March 2020 to January 2021 may have introduced some bias that should be taken into account.

5.2. Future Lines of Research

Regarding new lines of research, verification of the factorial structure of the PSI-4 LF requires the development of new studies. For a more comprehensive understanding of the PSI, it is essential to examine a new model that incorporates oblique relationships or mediation functions between the subscales. This model will facilitate the identification of advantages or disadvantages from a clinical perspective, thereby enhancing our ability to predict and diagnose psychological conditions.

Furthermore, although self-reports have demonstrated robust psychometric properties, the potential of a mixed-methods assessment strategy warrants further investigation. Currently, most studies with clinical samples rely on self-reporting; using observational, physiological, or performance assessment methods could help us better understand how parents experience parenting stress.

There is considerable heterogeneity in parenting experiences among parents, depending on their background, culture, educational level, and gender. Therefore, it is necessary to refine and detail the psychometric performance of the measure among different groups of parents (mothers versus fathers, parents by gender, low socioeconomic status, and single-parent families, among others).